McMahon–Hussein Correspondence

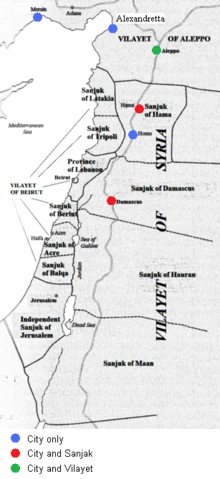

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence, or the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence, was a series of ten letters exchanged from July 1915 to March 1916,[1] during World War I, between Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, and Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner in the Sultanate of Egypt, concerning the political status of lands under the Ottoman Empire. Growing Arab nationalism had led to a desire for independence from the Ottoman Empire. In the letters Britain agreed to recognize Arab independence after World War I "in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca", with the exception of "portions of Syria" lying to the west of "the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo". This was in exchange for Arab help in fighting the Ottomans, led by Hussein bin Ali.

Later, the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement between France and the UK was exposed showing that the two countries were planning to split and occupy parts of the territory. Then, following the 1917 Balfour Declaration, the Sharif and other Arab leaders considered the Declaration a violation of previous agreements made in the correspondence. Palestine is not explicitly mentioned in the correspondence, and territories which were not purely Arab were excluded by McMahon and Hussein, although historically Palestine had long been included in historic Syria.[2] The Arabs, taking Palestine to be overwhelmingly Arab, claimed the declaration was in contrast to the letters, which promised the Arab independence movement control of the Middle East territories "in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca" in exchange for revolting against the Ottoman Empire during World War I. A debate over whether the Declaration was a violation of the McMahon agreement has continued until the present.

In January 1923 unofficial excerpts were published by Joseph N. M. Jeffries in The Daily Mail[3] and copies of the various letters circulated in the Arab press.[4] Excerpts were published in the 1937 Peel Commission Report,[5] and the correspondence was first published in full in George Antonius's 1938 The Arab Awakening,[6] then officially in 1939.[7] In 1964, further documents were declassified.[8]

Background

When Kitchener was Consul-General in Egypt , contacts between Abdullah I bin al-Hussein and Kitchener had eventually culminated in a telegram of 1 November 1914, from Kitchener (recently appointed as Secretary of War) to Hussein wherein Great Britain would, in exchange for support from the Arabs of Hejaz,

“...guarantee the independance, rights and privileges of the Sharifate against all foreign external foreign aggression, in particular that of the Qttomans”[9]

The Sharif indicated that he could not break with the Ottomans immediately. However, the entry of the Ottomans on Germany's side in World War I on 11 November 1914 brought about an abrupt shift in British political interests concerning an Arab revolt against the Ottomans.[10]

On his return journey from Istanbul in 1915, where Emir Faisal bin Hussein had confronted the Grand Vizier with evidence of an Ottoman plot to depose his father (Husayn bin Ali), he decided to visit Damascus to resume talks with the Arab secret societies al-Fatat and Al-'Ahd that he had met in March/April. On this occasion, Faisal joined their revolutionary movement. During this visit, on 23 May 1915, he was presented with the document that became known as the Damascus Protocol. The documents declared that the Arabs would revolt in alliance with the United Kingdom, and in return the UK would recognize the Arab independence in an area running from the 37th parallel near the Taurus Mountains on the southern border of Turkey, to be bounded in the east by Persia and the Persian Gulf, in the west by the Mediterranean Sea and in the south by the Arabian Sea.[11][12]

Following deliberations at Ta'if between Hussein and his sons in June 1915, during which Faisal counselled caution, Sherif Husayn bin Ali argued against rebellion and Abdullah advocated action and encouraged his father to enter into correspondence with Sir Henry McMahon;over the period July 14, 1915 to March 10, 1916, a total of 10 letters, 5 from each side, were exchanged between Sir Henry McMahon and Sherif Hussein. Hussein's letter of 18 February 1916 appealed to McMahon for £50,000 in gold plus weapons, ammunition and food claiming that Feisal was awaiting the arrival of ‘not less than 100,000 people’ for the planned revolt and McMahon's reply of 10 March 1916 confirmed British agreement to the requests and concluded the ten letters of the correspondence. The Sharif set a tentative date for armed revolt for June 1916 and commenced tactical discussions with the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon.[11]

Territorial reservations

The letter from McMahon to Hussein dated 24 October 1915 declared Britain's willingness to recognize the independence of the Arabs subject to certain exemptions. Note that the original correspondence was conducted in both English and Arabic, such that various slightly differing English translations are extant.

The districts of Mersina and Alexandretta, and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, cannot be said to be purely Arab, and must on that account be excepted from the proposed limits and boundaries.

With the above modification and without prejudice to our existing treaties concluded with Arab Chiefs, we accept these limits and boundaries, and in regard to the territories therein in which Great Britain is free to act without detriment to interests of her ally France, I am empowered in the name of the Government of Great Britain to give the following assurance and make the following reply to your letter:

Subject to the above modifications, Great Britain is prepared to recognize and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca.[13]

Declassified British Cabinet Papers include a telegram dated 19 October 1915 from Sir Henry McMahon to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Grey, requesting instructions.[14] McMahon said the clause had been suggested by a man named Muhammed Sharif al-Faruqi, a member of the Abd party, to satisfy the demands of the Syrian Nationalists for the independence of Arabia. Faroqi had said that the Arabs would fight if the French attempted to occupy the cities of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, but he thought they would accept some modification of the North-Western boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca. Faroqi suggested the language: "In so far as Britain was free to act without detriment to the interests of her present Allies, Great Britain accepts the principle of the independence of Arabia within limits propounded by the Sherif of Mecca." Lord Grey authorized McMahon to pledge the areas requested by the Sherif subject to the reserve for the Allies.

Arab Revolt

McMahon's promises were seen by the Arabs as a formal agreement between them and the United Kingdom. Lloyd George and Arthur Balfour represented the agreement as a treaty during the post war deliberations of the Council of Four. On this understanding the Arabs established a military force under the command of Hussein's son Faisal which fought, with inspiration from 'Lawrence of Arabia', against the Ottoman Empire during the Arab Revolt.[15] In an intelligence memo written in January 1916 Lawrence described the Arab Revolt as

beneficial to us, because it marches with our immediate aims, the break up of the Islamic 'bloc' and the defeat and disruption of the Ottoman Empire, and because the states [Sharif Hussein] would set up to succeed the Turks would be … harmless to ourselves … The Arabs are even less stable than the Turks. If properly handled they would remain in a state of political mosaic, a tissue of small jealous principalities incapable of cohesion (emphasis in original).[16]

The Arab Revolt began in June 1916, when an Arab army of around 70,000 men moved against Ottoman forces. They participated in the capture of Aqabah and the severing of the Hejaz railway, a vital strategic link through the Arab peninsula which ran from Damascus to Medina. This enabled the Egyptian Expeditionary Force under the command of General Allenby to advance into the Ottoman territories of Palestine and Syria.[17]

The British advance culminated in the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918 and the capitulation of Turkey on 31 October 1918.

The Arab revolt is seen by historians as the first organized movement of Arab nationalism. It brought together different Arab groups for the first time with the common goal to fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire. Much of the history of Arabic independence stemmed from the revolt beginning with the kingdom founded by Hussein. After the war was over, the Arab revolt had implications. Groups of people were put into classes based on if they had fought in the revolt or not and what their rank was. In Iraq, a group of Sharifian Officers from the Arab Revolt formed a political party which they were head of. Still to this day the Hashemite kingdom in Jordan is influenced by the actions of Arab leaders in the revolt.[18]

Legal Status of the Correspondence

Elie Kedourie says that the letter was not a treaty, and even if it were considered to be a treaty, Hussein completely failed to fulfill his promises from his 18 February 1916 letter.[19] Arguing to the contrary, Victor Kattan firstly describes the correspondence as a “secret treaty” and references The Secret Treaties of History that includes the correspondence. He further argues that Her Majesty’s Government considered it to be a treaty during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference negotiations with the French over the disposition of Ottoman territory.[20]

Subsequent commitments

Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement between Britain, France and Russia of May 1916 was exposed in December 1917 (made public by the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution) showing that the countries were planning to split and occupy parts of the promised Arab country. Hussein was satisfied by two disingenuous telegrams from Sir Reginald Wingate, who had replaced McMahon as High Commissioner of Egypt, assuring him that the British commitments to the Arabs were still valid and that the Sykes–Picot Agreement was not a formal treaty.[21]

Balfour Declaration

In 1917 Britain issued the Balfour Declaration, promising to support the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.

Hogarth message

Hussein asked for an explanation of the Balfour Declaration and in January 1918 Commander David Hogarth, head of the Arab Bureau in Cairo, was dispatched to Jeddah to deliver a letter written by Sir Mark Sykes on behalf of the British Government to Hussein (now King of Hejaz). The Hogarth message assured Hussein that "the Arab race shall be given full opportunity of once again forming a nation in the world" and referred to "...the freedom of the existing population both economic and political,...". Friedman and Kedourie argue that Hussein accepted the Balfour Declaration [22][23] while Charles D.Smith argues that both Friedman and Kedourie misrepresent documents and violate scholarly standards in order to reach their conclusions.[24] Hogarth reported that Hussein "would not accept an independent Jewish State in Palestine, nor was I instructed to warn him that such a state was contemplated by Great Britain".[25]

Declaration to the Seven

In light of the existing McMahon–Hussein correspondence, but in the wake of the seemingly competing Balfour Declaration for the Zionists, as well as the publication weeks later by the Bolsheviks of the older and previously secret Sykes–Picot Agreement with the Russians and French, seven Syrian notables in Cairo, from the newly formed Syrian Party of Unity (Hizb al-Ittibad as-Suri), issued a memorandum requesting some clarification from the British Government, including a "guarantee of the ultimate independence of Arabia". In response, issued on 16 June 1918, the Declaration to the Seven, stated the British policy that the future government of the regions of the Ottoman Empire occupied by Allied forces in World War I should be based on the consent of the governed.[26][27]

Allenby's assurance to Faisal

On 19 October 1918, General Allenby reported to the British Government that he had given Faisal,

official assurance that whatever measures might be taken during the period of military administration they were purely provisional and could not be allowed to prejudice the final settlement by the peace conference, at which no doubt the Arabs would have a representative. I added that the instructions to the military governors would preclude their mixing in political affairs, and that I should remove them if I found any of them contravening these orders. I reminded the Amir Faisal that the Allies were in honour bound to endeavour to reach a settlement in accordance with the wishes of the peoples concerned and urged him to place his trust whole-heartedly in their good faith.[28]

Anglo-French Declaration of 1918

In the Anglo-French Declaration of 7 November 1918 the two governments stated that

The object aimed at by France and the United Kingdom in prosecuting in the East the War let loose by the ambition of Germany is the complete and definite emancipation of the peoples so long oppressed by the Turks and the establishment of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the initiative and free choice of the indigenous populations.[29]

According to civil servant Eyre Crowe who saw the original draft of the Declaration, "we had issued a definite statement against annexation in order (1) to quiet the Arabs and (2) to prevent the French annexing any part of Syria".[30]

Paris Peace Conference

Following World War I, the Paris Peace Conference was held in 1919 between the allies to agree territorial divisions. It was a well known fact that France wanted a Syrian protectorate. At the conference, Prince Faisal, speaking on behalf of King Hussein, did not ask for immediate Arab independence. He recommended an Arab State under a British Mandate.[31]

Independent Kingdom of Syria

On 6 January 1920 Prince Faisal initialed an agreement with French Prime Minister Clemenceau which acknowledged 'the right of the Syrians to unite to govern themselves as an independent nation'.[32] A Pan-Syrian Congress, meeting in Damascus, declared an independent state of Syria on 8 March 1920. The new state included portions of Syria, Palestine, and northern Mesopotamia which had been set aside under the Sykes–Picot Agreement for an independent Arab state, or confederation of states. King Faisal was declared the head of State. The San Remo conference was hastily convened, and the United Kingdom and France both agreed to recognize the provisional independence of Syria and Mesopotamia, while 'reluctantly' claiming mandates to assist in their administration. Provisional recognition of Palestinian independence was not mentioned, despite the fact that it was designated a Class A Mandate.

France had decided to govern Syria directly, and took action to enforce the French Mandate of Syria before the terms had been accepted by the Council of the League of Nations. The French intervened militarily at the Battle of Maysalun in June 1920. They deposed the indigenous Arab government, and removed King Faisal from Damascus in August 1920.[33] The United Kingdom also appointed a High Commissioner and established their own mandatory regime in Palestine, without first obtaining approval from the Council of the League of Nations.

League of Nations mandates

After the war, France and Britain continued to provide assurances of Arab independence, while planning to place the entire region under their own administration.[34][35]

United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing was a member of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace at Paris in 1919. He explained that the system of mandates was simply a device created by the Great Powers to conceal their division of the spoils of war, under the color of international law. If the territories had been ceded directly, the value of the former German and Ottoman territories would have been applied to offset the Allies claims for war reparations. He also explained that Jan Smuts had been the author of the original concept.[36]

Both Zionist and Arab representatives attended the Peace conference, having both signed the Faisal–Weizmann Agreement,[37] a short-lived agreement for Arab–Jewish cooperation on the development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine and an Arab nation in a large part of the Middle East. The agreement was never implemented.

At the same conference, US Secretary of State Lansing had asked Dr. Weizmann if the Jewish national home meant the establishment of an autonomous Jewish government. The head of the Zionist delegation had replied in the negative.[38]

At the Conference of London and the San Remo conference in April 1920, the Allied Supreme Council granted the mandates for Palestine and Mesopotamia to Britain,[39] and those for Syria and Lebanon to France.

Lawrence's post-war advocacy

Lawrence became increasingly guilt-ridden by the knowledge that Britain did not intend to abide by the commitments made to the Sharif, but still managed to convince Faisal that it would be to the Arabs' advantage to go on fighting the Ottomans. At the Versailles peace conference in 1919 and the Cairo conference in 1921 Lawrence lobbied for Arab independence, but his belated attempts to maintain the territorial integrity of Arab lands, which he had promised to Hussein and Faisal, and in limiting France's influence in what later became Syria and Lebanon were fruitless. However, as Churchill's adviser on Arab affairs (1921–22) Lawrence was able to lobby for a considerable degree of autonomy for Mesopotamia and Transjordan. The British placed Palestine, promised to the Zionist Federation in 1917, under mandate with a civilian administration headed by Herbert Samuel, and divided their remaining territory in the Middle East into the kingdoms of Iraq and Transjordan, assigning them to Faisal and his brother Abdullah, respectively.[16][40]

Debate about Palestine

Translation

The correspondence was written first in English before being translated to Arabic and vice versa. Who wrote and translated it is unclear. Kedourie and others have assumed that the likeliest candidate for primary author was Ronald Storrs. In his memoirs, Storrs says that correspondence was prepared by Husayn Ruhi [41] and then checked by himself.[42]

The Arab delegations to the 1939 Conference had objected to certain translations of Arabic to English and the Committee arranged for mutually agreeable translations that would render the English text “free from actual error”.[43]

Debated sentences

(i) First alternative: McMahon was completely ignorant of Ottoman administrative geography. He did not know that the Ottoman vilayet of Aleppo extended westward to the coast, and he did not know that there were no Ottoman vilayets of Homs and Hama. It seems to me incredible that McMahon can have been as ill-informed as this, and that he would not have taken care to inform himself correctly when he was writing a letter in which he was making very serious commitments on HMG's account.

(ii) Second alternative: McMahon was properly acquainted with Ottoman administrative geography, and was using the word 'wilayahs' equivocally. Apropos of Damascus, he was using it to mean 'Ottoman provinces'; apropos of Homs and Hama, and Aleppo, he was using it to mean 'environs'. This equivocation would have been disingenuous, impolitic, and pointless. I could not, and still cannot, believe that McMahon behaved so irresponsibly"

The documents written by British officials, contesting the interpretation of McMahon's word 'wilayahs' that was made by me and, before me, by the author of the Arab Bureau's History, all date from after the time at which HMG had become sure that Britain had Palestine in her pocket... I do not think that Young's or Childs' or Mr Friedman's interpretation of McMahon's use of the word 'wilayahs' is tenable. After studying Mr Friedman's paper and writing these notes, I am inclined to think that the drafting of this letter was, not disingenuous, but hopelessly muddle-headed. Incompetence is not excusable in transacting serious and responsible public business."

Arnold J. Toynbee in 1970, in correspondence with Isaiah Friedman[44]

The debate regarding Palestine derived from the fact that it is not explicitly mentioned in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence, but is included within the boundaries that were initially proposed by Hussein. McMahon accepted the boundaries of Hussein "subject to modification",[45] and suggested the modification that "portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab and should be excluded." The Arabs and British disagreed over whether Palestine was meant to be one of those excluded areas, each side producing supporting arguments for their positions based on fine details of the wording and the historical circumstances of the correspondence.

Jonathan Schneer provides an analogy to explain the central dispute over the meaning:

Presume a line extending from the districts of New York, New Haven, New London, and Boston, excluding territory west from an imaginary coastal kingdom. If by districts one means "vicinity" or "environs," that is one thing with regard to the land excluded, but if one means "vilayets" or "provinces," or in the American instance "states," it is another altogether. There are no states of Boston, New London, or New Haven, just as there were no provinces of Hama and Homs, but there is a state of New York, just as there was a vilayet of Damascus, and territory to the west of New York State is different from territory to the west of the district of New York, presumably New York City and environs, just as territory to the west of the vilayet of Damascus is different from territory to the west of the district of Damascus, presumably the city of Damascus and its environs.[46]

In the letter of 24 October, the English version is as follows:

“...,we accept those limits and boundaries; and in regard to those portions of the territories therein in which Great Britain is free to act without detriment to the interests of her ally France”

At a meeting in Whitehall in December 1920 the English and Arabic texts of McMahon’s correspondence with Sharif Husein were compared. As one official, who was present, put it,

In the Arabic version sent to King Husain this is so translated as to make it appear that Gt Britain is free to act without detriment to France in the whole of the limits mentioned. This passage of course had been our sheet anchor: it enabled us to tell the French that we had reserved their rights, and the Arabs that there were regions in which they wd have eventually to come to terms with the French. It is extremely awkward to have this piece of solid ground cut from under our feet. I think that HMG will probably jump at the opportunity of making a sort of amende by sending Feisal to Mesopotamia.

Barr argues that although McMahon had intended to reserve the French interests, he became a victim of his own cleverness since the translator Ruhi lost the qualifying sense of the sentence in the Arabic version.[47][lower-alpha 1]

Arab interpretation

The Arab position was that they could not refer to Palestine since that lay well to the south of the named places. In particular, the Arabs argued that the vilayet (province) of Damascus did not exist and that the district (sanjak) of Damascus covered only the area surrounding the city itself and furthermore that Palestine was part of the vilayet of 'Syria A-Sham', which was not mentioned in the exchange of letters.[15]

Supporters of this interpretation also note that during the war, thousands of proclamations were dropped in all parts of Palestine, carrying a message from the Sharif Hussein on one side and a message from the British Command on the other, to the effect 'that an Anglo-Arab agreement had been arrived at securing the independence of the Arabs.'[48]

British interpretation

The undated memorandum, GT 6185 (from CAB 24/68/86 as seen at left) of November 1918 [50] was prepared by the renowned British historian Arnold Toynbee in 1918, while working as a temporary Foreign Office clerk in the Political Intelligence Department. Crowe, then The Permanent Under-Secretary, ordered them put in the Foreign Office dossier for the Peace Conference. After arriving in Paris, General Jan Smuts required that the memoranda be summarized and Toynbee produced the document GT 6506 [51] (maps illustrating it are GT6506A [52] ). These two last were circulated as E.C.2201 and considered at a meeting of the Eastern Committee (No.41) of the Cabinet on 5 December 1918 [53] chaired by Curzon ( General Jan Smuts, Lord Balfour, Lord Robert Cecil, General Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and representatives of the Foreign Office, the India Office, the Admiralty, the War Office, and the Treasury were present. T. E. Lawrence also attended.)[54]

The Eastern Committee met nine times in November and December to draft a set of resolutions on British policy for the benefit of the negotiators.[55]On 21 October, the War Cabinet asked Smuts to prepare the peace brief in summary form and he asked Erle Richards to carry out this task. Toynbee’s GT6506 and the resolutions of the Eastern Committee were distilled by Richards into a “P-memo” (P-49, as seen at left) for use by the Peace Conference delegates.[56][57]

In the public arena, Balfour had come under criticism in the House of Commons, when the Liberals and Labor Socialists moved a resolution 'That secret treaties with the allied governments should be revised, since, in their present form, they are inconsistent with the object for which this country entered the war and are, therefore, a barrier to a democratic peace.'[58] In response to growing criticism arising from the seemingly contradictory commitments undertaken by the United Kingdom in the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, the Sykes–Picot Agreement and the Balfour declaration[59] the 1922 Churchill White Paper, took the position that Palestine had always been excluded from the Arab area. Although this directly contradicted numerous previous government documents, those documents were not known to the public at the time. As part of preparing this White Paper, Sir John Shuckburgh of the British Colonial Office had exchanged correspondence with McMahon, and reliance was placed on a 1920 memorandum by Major Hubert Young, who had noted that in the original Arabic text, the word translated as "districts" in English was "vilayets", a vilayet being the largest class of administrative district into which the Ottoman Empire was divided. He concluded that "district of Damascus", i.e., "vilayet of Damascus", must have referred to the vilayet of which Damascus was the capital, the Vilayet of Syria. This vilayet extended southward to the Gulf of Aqaba, but excluded most of Palestine.

While the British Government have held that the intent of the McMahon Correspondence was not to promise Palestine to Hussein, it has occasionally acknowledged the flaws in the legal terminology of the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence that make this position problematic. For example, the weak points of the government's interpretation were acknowledged in a detailed memorandum by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in 1939. [60][lower-alpha 2]

A committee established by the British in 1939 to clarify the various arguments observed that many commitments had been made during and after the war - and that all of them would have to be studied together. The Arab representatives submitted a statement to the committee from Sir Michael McDonnell[61] which explained that whatever McMahon had intended to mean was of no legal consequence, since it was his actual statements that constituted the pledge from His Majesty's Government. The Arab representatives also pointed out that McMahon had been acting as an intermediary for the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Grey. Speaking in the House of Lords on 27 March 1923, Lord Grey had made it clear that, for his part, he entertained serious doubts as to the validity of the Churchill White Paper's interpretation of the pledges which he, as Foreign Secretary, had caused to be given to the Sharif Husain in 1915. [lower-alpha 3] The Arab representatives suggested that a search for evidence in the files of the Foreign Office might throw light on the Secretary of State's intentions.

List of British interpretations over time

A list of interpretations by British politicians and civil servants is below, showing the evolution of the debate between 1916 and 1939:

| Source | Context | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Henry McMahon 26 October 1915 |

Dispatch to British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey | "I have been definite in stating that Great Britain will recognise the principle of Arab independence in purely Arab territory... but have been equally definite in excluding Mersina, Alexandretta and those districts on the northern coasts of Syria, which cannot be said to be purely Arab, and where I understand that French interests have been recognised. I am not aware of the extent of French claims in Syria, nor of how far His Majesty's Government have agreed to recognise them. Hence, while recognising the towns of Damascus, Hama, Homs and Aleppo as being within the circle of Arab countries, I have endeavoured to provide for possible French pretensions to those places by a general modification to the effect that His Majesty's Government can only give assurances in regard to those territories "in which she can act without detriment to the interests of her ally France.""[63][64][65][66] |

| Arab Bureau for Henry McMahon 19 April 1916 |

Memorandum sent by Henry McMahon to the Foreign Office[67] | Interpreted Palestine as being included in the Arab area:[68]"What has been agreed to, therefore, on behalf of Great Britain is: (1) to recognise the independence of those portions of the Arab-speaking areas in which we are free to act without detriment to the interests of France. Subject to these undefined reservations the said area is understood to be bounded N. by about lat. 37, east by the Persian frontier, south by the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, west by the Red Sea and the Mediterranean up to about lat. 33, and beyond by an indefinite line drawn inland west of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo: all that lies between this last line and the Mediterranean being, in any case, reserved absolutely for future arrangement with the French and the Arabs."[69][70] |

| War Office 1 July 1916 |

The Sherif of Mecca and the Arab Movement | Adopted the same conclusions as the Arab Bureau memorandum of April 1916[71] |

| Arab Bureau 29 November 1916 |

Summary of Historical Documents: Hedjaz Rising Narrative | Included the memorandum of April 1916[72][73][74] |

| Arnold J. Toynbee, Foreign Office Political Intelligence Department November 1918 and 21 November 1918 |

War Cabinet Memorandum on British Commitments to King Husein

|

"With regard to Palestine, His Majesty's Government are committed by Sir H. McMahon's letter to the Sherif on the 24th October, 1915, to its inclusion in the boundaries of Arab independence. But they have stated their policy regarding the Palestinian Holy Places and Zionist colonisation in their message to him of the 4th January, 1918."[75][76][77][78]

|

| Lord Curzon 5 Dec 1918 |

Chairing the Eastern Committee of the British War Cabinet | "First, as regards the facts of the case. The various pledges are given in the Foreign Office paper [E.C. 2201] which has been circulated, and I need only refer to them in the briefest possible words. In their bearing on Syria they are the following: First there was the letter to King Hussein from Sir Henry McMahon of the 24th October 1915, in which we gave him the assurance that the Hedjaz, the red area which we commonly call Mesopotamia, the brown area or Palestine, the Acre-Haifa enclave, the big Arab areas (A) and (B), and the whole of the Arabian peninsula down to Aden should be Arab and independent." "The Palestine position is this. If we deal with our commitments, there is first the general pledge to Hussein in October 1915, under which Palestine was included in the areas as to which Great Britain pledged itself that they should be Arab and independent in the future . . . the United Kingdom and France - Italy subsequently agreeing - committed themselves to an international administration of Palestine in consultation with Russia, who was an ally at that time . . . A new feature was brought into the case in November 1917, when Mr Balfour, with the authority of the War Cabinet, issued his famous declaration to the Zionists that Palestine 'should be the national home of the Jewish people, but that nothing should be done - and this, of course, was a most important proviso - to prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine. Those, as far as I know, are the only actual engagements into which we entered with regard to Palestine."[83][84][85] |

| H. Erle Richards January 1919 |

Peace Conference: Memorandum Respecting Palestine, for the Eastern Committee of the British War Cabinet, ahead of the Paris Peace Conference[49] | "A general pledge was given to Husein in October, 1915, that Great Britain was prepared (with certain exceptions) to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs with the territories included in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca; and Palestine was within those territories. This pledge was restricted to those portions of the territories in which Great Britain was free to act without detriment to the interests of her Ally, France."[49][86] |

| Arthur Balfour 19 August 1919 |

Memorandum by Mr. Balfour respecting Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia | "In 1915 we promised the Arabs independence; and the promise was unqualified, except in respect of certain territorial reservations... In 1915 it was the Sherif of Mecca to whom the task of delimitation was to have been confided, nor were any restrictions placed upon his discretion in this matter, except certain reservations intended to protect French interests in Western Syria and Cilicia."[87][88] |

| Hubert Young, of the British Foreign Office 29 November 1920 |

Memorandum on Palestine Negotiations with the Hedjaz, written prior to the arrival of Faisal bin Hussein in London on 1 December 1920.[89] | Interpreted the Arabic translation to be referring to the Vilayet of Damascus.[90] The was the first time an argument was put forward that the correspondence was intended to exclude Palestine from the Arab area.[91][70]: "With regard to Palestine, a literal interpretation of Sir H. McMahon's undertaking would exclude from the areas in which His Majesty's Government were prepared to recognize the 'independence of the Arabs' only that portion of the Palestine mandatory area [which included 'Transjordan '] which lies to the west of the 'district of Damascus'. The western boundary of the 'district of Damascus' before the war was a line bisecting the lakes of Huleh and Tiberias; following the course of the Jordan; bisecting the Dead Sea; and following the Wadi Araba to the Gulf of Akaba.'"[92] |

| Eric Forbes Adam October 1921 |

Letter to John Evelyn Shuckburgh | "On the wording of the letter alone, I think either interpretation is possible, but I personally think the context of that particular McMahon letter shows that McMahon (a) was not thinking in terms of vilayet boundaries etc., and (b) meant, as Hogarth says, merely to refer to the Syrian area where French interests were likely to be predominant and this did not come south of the Lebanon. ... Toynbee, who went into the papers, was quite sure his interpretation of the letter was right and I think his view was more or less accepted until Young wrote his memorandum."[3] |

| David George Hogarth 1921 |

A talk delivered in 1921 | "...that Palestine was part of the area in respect to which we undertook to recognise the independence of the Arabs"[25] |

| T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) February 1922 (first published 1926) |

Autobiography: Seven Pillars of Wisdom, widely publicized[93] | "The Arab Revolt had begun on false pretences. To gain the Sherif's help our Cabinet had offered, through Sir Henry McMahon, to support the establishment of native governments in parts of Syria and Mesopotamia, 'saving the interests of our ally, France'. The last modest clause concealed a treaty (kept secret, till too late, from McMahon, and therefore from the Sherif) by which France, England and Russia agreed to annex some of these promised areas, and to establish their respective spheres of influence over all the rest... Rumours of the fraud reached Arab ears, from Turkey. In the East persons were more trusted than institutions. So the Arabs, having tested my friendliness and sincerity under fire, asked me, as a free agent, to endorse the promises of the British Government. I had had no previous or inner knowledge of the McMahon pledges and the Sykes-Picot treaty, which were both framed by war-time branches of the Foreign Office. But, not being a perfect fool, I could see that if we won the war the promises to the Arabs were dead paper. Had I been an honourable adviser I would have sent my men home, and not let them risk their lives for such stuff. Yet the Arab inspiration was our main tool in winning the Eastern war. So I assured them that England kept her word in letter and spirit. In this comfort they performed their fine things: but, of course, instead of being proud of what we did together, I was continually and bitterly ashamed."[94] |

| Henry McMahon 12 March 1922 and 22 July 1937 |

Letter to John Evelyn Shuckburgh, in preparation for the Churchill White Paper

|

"It was my intention to exclude Palestine from independent Arabia, and I hoped that I had so worded the letter as to make this sufficiently clear for all practical purposes. My reasons for restricting myself to specific mention of Damascus, Hama, Homs and Aleppo in that connection in my letter were: 1) that these were places to which the Arabs attached vital importance and 2) that there was no place I could think of at the time of sufficient importance for purposes of definition further South of the above. It was as fully my intention to exclude Palestine as it was to exclude the more Northern coastal tracts of Syria."[95]

|

| Winston Churchill 3 June 1922 and 11 July 1922 |

Churchill White Paper following the 1921 Jaffa riots

|

"In the first place, it is not the case, as has been represented by the Arab Delegation, that during the war His Majesty's Government gave an undertaking that an independent national government should be at once established in Palestine. This representation mainly rests upon a letter dated 24 October 1915, from Sir Henry McMahon, then His Majesty's High Commissioner in Egypt, to the Sharif of Mecca, now King Hussein of the Kingdom of the Hejaz. That letter is quoted as conveying the promise to the Sherif of Mecca to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories proposed by him. But this promise was given subject to a reservation made in the same letter, which excluded from its scope, among other territories, the portions of Syria lying to the west of the District of Damascus. This reservation has always been regarded by His Majesty's Government as covering the vilayet of Beirut and the independent Sanjak of Jerusalem. The whole of Palestine west of the Jordan was thus excluded from Sir. Henry McMahon's pledge."

|

| Duke of Devonshire's Colonial Office 17 February 1923 |

British Cabinet Memorandum regarding Policy in Palestine | "The question is: Did the excluded area cover Palestine or not? The late Government maintained that it did and that the intention to exclude Palestine was clearly under stood, both by His Majesty's Government and by the Sherif, at the time that the correspondence took place. Their view is supported by the fact that in the following year (1916) we concluded an agreement with the French and Russian Governments under which Palestine was to receive special treatment-on an international basis. The weak point in the argument is that, on the strict wording of Sir H. McMahon's letter, the natural meaning of the phrase "west of the district of Damascus" has to be somewhat strained in order to cover an area lying considerably to the south, as well as to the west, of the City of Damascus."[75][97] |

| Duke of Devonshire 27 March 1923 |

Diary of 9th Duke of Devonshire, Chatsworth MSS | “Expect we shall have to publish papers about pledges to Arabs. They are quite inconsistent, but luckily they were given by our predecessors.”[98] |

| Edward Grey 27 March 1923 |

Debate in the House of Lords; Viscount Grey had been Foreign Secretary in 1915 when the letters were written | "I do not propose to go into the question whether the engagements are inconsistent with one another, but I think it is exceedingly probable that there are inconsistencies... A considerable number of these engagements, or some of them, which have not been officially made public by the Government, have become public through other sources. Whether all have become public I do not know, but. I seriously suggest to the Government that the best way of clearing our honour in this matter is officially to publish the whole of the engagements relating to the matter, which we entered into during the war... I regarded [the Balfour Declaration] with a certain degree of sentiment and sympathy. It is not from any prejudice with regard to that matter that I speak, but I do see that the situation is an exceedingly difficult one, when it is compared with the pledges which undoubtedly were given to the Arabs. It would be very desirable, from the point of view of honour, that all these various pledges should be set out side by side, and then, I think, the most honourable thing would be to look at them fairly, see what inconsistencies there are between them, and, having regard to the nature of each pledge and the date at which it was given, with all the facts before us, consider what is the fair thing to be done."[99][100][101] |

| Lord Islington 27 March 1923 |

Debate in the House of Lords | "the claim was made by the British Government to exclude from the pledge of independence the northern portions of Syria... It was described as being that territory which lay to the west of a line from the city of Damascus... up to Mersina... and, therefore, all the rest of the Arab territory would come under the undertaking... Last year Mr. Churchill, with considerable ingenuousness, of which, when in a difficult situation, he is an undoubted master, produced an entirely new description of that line."[99][101] |

| Lord Buckmaster 27 March 1923 |

Debate in the House of Lords; Buckmaster had been Lord Chancellor in 1915 when the letters were written and voted against the 1922 White Paper in the House of Lords.[102] | "these documents show that, after an elaborate correspondence in which King Hussein particularly asked to have his position made plain and definite so that there should be no possibility of any lurking doubt as to where he stood as from that moment, he was assured that within a line that ran north from Damascus through named places, a line that ran almost due north from the south and away to the west, should be the area that should be he excluded from their independence, and that the rest should be theirs."[99][101] |

| Gilbert Clayton 12 April 1923 |

An unofficial note given to Herbert Samuel, described by Samuel in 1937, eight years after Clayton's death[103] | "I can bear out the statement that it was never the intention that Palestine should be included in the general pledge given to the Sharif; the introductory words of Sir Henry’s letter were thought at that time—perhaps erroneously—clearly to cover that point."[103][104] |

| Gilbert Clayton 11 March 1919 |

Memorandum, 11.3.1919. Lloyd George papers F/205/3/9. House of Lords. | "We are committed to three distinct policies in Syria and Palestine:-

A. We are bound by the principles of the Anglo-French Agreement of 1916 [Sykes-Picot], wherein we renounced any claim to predominant influence in Syria. B. Our agreements with King Hussein . . . have pledged us to support the establishment of an Arab state, or confederation of states, from which we cannot exclude the purely Arab portions of Syria and Palestine. C. We have definitely given our support to the principle of a Jewish home in Palestine and, although the initial outlines of the Zionist programme have been greatly exceeded by the proposals now laid before the Peace Congress, we are still committed to a large measure of support to Zionism. The experience of the last few months has made it clear that these three policies are incompatible ... "[105] |

| Lord Passfield, Secretary of State for the Colonies 25 July 1930 |

Memorandum to Cabinet: "Palestine: McMahon Correspondence" | “The question whether Palestine was included within the boundaries of the proposed Arab State is in itself extremely complicated. From an examination of Mr. Childs’s able arguments, I have formed the judgement that there is a fair case for saying that Sir H. McMahon did not commit His Majesty’s Government in this sense. But I also have come to the conclusion that there is much to be said on both sides and that the matter is one for the eventual judgement of the historian, and not one in which a simple, plain and convincing statement can be made.”[106][107] |

| Drummond Shiels, Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies 1 August 1930 |

House of Commons debate | Lord Passfield, in his memorandum, suggested to the Cabinet the wording of a statement that could be made in reply to a question in the House of Commons and the statement was subsequently made in the House of Commons on 1 August.[108] |

| W. J. Childs, of the British Foreign Office 24 October 1930 |

Memorandum on the Exclusion of Palestine from the Area assigned for Arab Independence by McMahon–Hussein Correspondence of 1915-16 | Interpreted Palestine as being excluded from the Arab area:[109][110] “...the interests of France so reserved in Palestine must be taken as represented by the origins French claim to possession of the whole of Palestine. And, therefore, that the general reservation of French interests is sufficient by itself to exclude Palestine from the Arab area.”[111] |

| Reginald Coupland, commissioner on the Palestine Royal Commission 5 May 1937 |

Explanation to the Foreign Office regarding the Commission’s abstention[112] | "a reason why the Commission did not intend to pronounce upon Sir H. McMahon’s pledge was that in everything else their report was unanimous, but that upon this point they would be unlikely to prove unanimous."[112] |

| George William Rendel, Head of the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office 26 July 1937 |

Minute commenting on McMahon’s 23 July 1937 letter | "My own impression from reading the correspondence has always been that it is stretching the interpretation of our caveat almost to breaking point to say that we definitely did not include Palestine, and the short answer is that if we did not want to include Palestine, we might have said so in terms, instead of referring vaguely to areas west of Damascus, and to extremely shadowy arrangements with the French, which in any case ceased to be operative shortly afterwards... It would be far better to recognise and admit that H.M.G. made a mistake and gave flatly contradictory promises - which is of course the fact."[113] |

| Lord Halifax, Foreign Secretary January 1939 |

Memorandum on Palestine: Legal Arguments Likely to be Advanced by Arab Representatives | "...it is important to emphasise the weak points in His Majesty's Governments case, e.g. :—

...It may be possible to produce arguments designed to explain away some of these difficulties individually (although even this does not apply in the case of (iv)), but it is hardly possible to explain them away collectively. His Majesty's Government need not on this account abjure altogether the counter-argument based on the meaning of the word "district," which have been used publicly for many years, and the more obvious defects in which do not seem to have been noticed as yet by Arab critics."[114][13] |

| Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence [115] 16 March 1939 |

Committee set up in preparation for the White Paper of 1939 | "It is beyond the scope of the Committee to express an opinion upon the proper interpretation of the various statements mentioned in paragraph 19 and such an opinion could not in any case be properly expressed unless consideration had also been given to a number of other statements made during and after the war. In the opinion of the Committee it is, however, evident from these statements that His Majesty's Government were not free to dispose of Palestine without regard for the wishes and interests of the inhabitants of Palestine, and that these statements must all be taken into account in any attempt to estimate the responsibilities which—upon any interpretation of the Correspondence—His Majesty's Government have incurred towards those inhabitants as a result of the Correspondence."[116][117] |

Interpretations of French intentions

In a Cabinet analysis of diplomatic developments prepared in May 1917, The Hon. William Ormsby-Gore, MP, argued that:

French intentions in Syria are surely incompatible with the war aims of the Allies as defined to the Russian Government. If the self-determination of nationalities is to be the principle, the interference of France in the selection of advisers by the Arab Government and the suggestion by France of the Emirs to be selected by the Arabs in Mosul, Aleppo, and Damascus would seem utterly incompatible with our ideas of liberating the Arab nation and of establishing a free and independent Arab State. The British Government, in authorising the letters despatched to King Hussein before the outbreak of the revolt by Sir Henry McMahon, would seem to raise a doubt as to whether our pledges to King Hussein as head of the Arab nation are consistent with French intentions to make not only Syria but Upper Mesopotamia another Tunis. If our support of King Hussein and the other Arabian leaders of less distinguished origin and prestige means anything it means that we are prepared to recognise the full sovereign independence of the Arabs of Arabia and Syria. It would seem time to acquaint the French Government with our detailed pledges to King Hussein, and to make it clear to the latter whether he or someone else is to be the ruler of Damascus, which is the one possible capital for an Arab State, which could command the obedience of the other Arabian Emirs.[118]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In his 'Setting the Desert on Fire' published 2 years earlier, Barr had explained things differently in describing how after being missing for nearly fifteen years, copies of the Arabic versions of the two most significant letters were found in a clear-out of Ronald Storrs’s office in Cairo. “This careless translation completely changes the meaning of the reservation, or at any rate makes the meaning exceedingly ambiguous,”the Lord Chancellor admitted, in a secret legal opinion on the strength of the Arab claim circulated to the cabinet on 23 January 1939.

- ↑ (i) the fact that the word “district” is applied not only to Damascus, &c., where the reading of vilayet is at least arguable, but also immediately previously to Mersina and Alexandretta. No vilayets of these names exist…and it would be difficult to argue that the word “districts” can have two completely different meanings in the space of a few lines. (ii) the fact that Homs and Hama were not the capitals of vilayets, but were both within the Vilayet of Syria. (iii) the fact that the real title of the “Vilayet of Damascus” was “Vilayet of Syria.” (iv) the fact that there is no land lying west of the Vilayet of Aleppo. The Foreign Secretary summarized “It may be possible to produce arguments designed to explain away some of these difficulties individually (although even this does not apply in the case of (iv)), but it is hardly possible to explain them away collectively. His Majesty’s Government need not on this account abjure altogether the counter-argument based on the meaning of the word “district,” which have been used publicly for many years, and the more obvious defects in which do not seem to have been noticed as yet by Arab critics.”

- ↑ Viscount Grey of Fallodon (McMahon’s superior when the correspondence was entered into) “A considerable number of these engagements, or some of them, which have not been officially made public by the Government, have become public through other sources. Whether all have become public I do not know, but. I seriously suggest to the Government that the best way of clearing our honour in this matter is officially to publish the whole of the engagements relating to the matter, which we entered into during the war. If they are found to be not inconsistent with one another our honour is cleared. If they turn out to be inconsistent, I 655 think it will be very much better that the amount, character and extent of the inconsistencies should be known, and that we should state frankly that, in the urgency of the war, engagements were entered into which were not entirely consistent with each other. I am sure that we cannot redeem our honour by covering up our engagements and pretending that there is no inconsistency, if there really is inconsistency. I am sure that the most honourable course will be to let it be known what the engagements are, and, if there is inconsistency, then to admit it frankly, and, admitting that fact, and having enabled people to judge exactly what is the amount of the inconsistency, to consider what is the most fair and honourable way out of the impasse into which the engagements may have led us. Without comparing one engagement with another, I think that we are placed in considerable difficulty by the Balfour Declaration itself. I have not the actual words here, but I think the noble Duke opposite will not find fault with my summary of it. It promised a Zionist home without prejudice to the civil and religious rights of the population of Palestine. A Zionist home, my Lords, undoubtedly means or implies a Zionist Government over the district in which the home is placed, and if 93 per cent. of the population of Palestine are Arabs, I do not see how you can establish other than an Arab Government, without prejudice to their civil rights. That one sentence alone of the Balfour Declaration seems to me to involve, without over-stating the case, very great difficulty of fulfilment.“[62]

References

- Biger, Gideon (2004). The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840-1947. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-5654-0.

- Choueiri, Youssef M. (2000). Arab Nationalism: A History. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-21729-0

- Cleveland, William L. (2004). A History of the Modern Middle East. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-4048-9 (see pp. 157–160).

- Federal Research Division (2004). Syria: A Country Study. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4191-5022-7

- Friedman, Isaiah (2000). Palestine, a Twice-Promised Land: The British, the Arabs & Zionism : 1915–1920. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-3044-7.

- Hughes, Matthew (1999). Allenby and British Strategy in the Middle East, 1917–1919. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4920-1

- Huneidi, Sahar (2001). A Broken Trust: Sir Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians. I.B.Tauris. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-86064-172-5.

- Kedouri, Elie (2014). In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth: The McMahon-Husayn Correspondence and Its Interpretations 1914-1939. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-30842-1.

- Kattan, Victor (June 2009). From coexistence to conquest: international law and the origins of the Arab-Israeli conflict, 1891–1949. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2579-8.

- Mansfield, Peter (2004). A History of the Middle East. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-303433-2 (see pp. 154–155).

- Milton-Edwards, Beverley (2006). Contemporary Politics in the Middle East. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-7456-3594-6

- Paris, Timothy J. (2003), Britain, the Hashemites, and Arab Rule, 1920-1925: The Sherifian Solution, Frank Cass, ISBN 978-0-7146-5451-5

- Schneer, Jonathan (2010). The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6532-5.

- Toynbee, Arnold; Friedman, Isaiah (1970). "The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence: Comments and a Reply" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary History. 5 (4): 185–201. JSTOR 259872.

- Hurewitz, J.C. (June 1979). The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics:A Documentary Record. British-French supremacy, 1914-1945 Vol.2. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300022032.

- Smith, Charles D. (1993). "The Invention of a Tradition The Question of Arab Acceptance of the Zionist Right to Palestine during World War I" (PDF). Journal of Palestine Studies. XXII (2): 48–61.

- Kalisman, Hilary Falb (2016). "The Little Persian Agent in Palestine: Husayn Ruhi, British Intelligence, and World War I" (PDF). Institute for Palestine Studies (66): 67.

- Storrs, Sir Ronald (June 1937). The Memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs. G.P.Putnam’s Sons.

- Morris, Benny (August 2001). Righteous Victims A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict 1881-2001. Random House, Vintage Books Ed.

- Smith, Charles D. (2011). "The Historiography of World War I and the Emergence of the Contemporary Middle East". In Gershoni, Israel; Singer, Amy; Erdem, Y.Kakan. Middle East Historiographies: Narrating the Twentieth Century. University of Washington Press. pp. 39–69. ISBN 9780295800899.

- Yapp, M.E. (2013). "Elie Kedourie and Middle East History". In Kedourie, Sylvia. Elie Kedourie's Approaches to History and Political Theory: 'The Thoughts and Actions of Living Men'. Routledge. pp. 31–54. ISBN 9781317970194.

- Hourani, Albert (1981). The Emergence of the Modern Middle East. The university of California Press. ISBN 9780520038622.

- Khouri, Fred John (January 1985). The Arab-Israeli Dilemma. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2340-3.

- Barr, James (2011). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East. Simon & Schuster. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-84983-903-7.

- [119]

- Wilson, Jeremy (1990). Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorized Biography of T.E. Lawrence. Atheneum. p. 1188. ISBN 9780689119347.

- Bennett, G.H. (1995). British foreign Policy during the Curzon Period, 1919-24. Macmillan Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-349-39547-7.

- Goldstein, Erik (1987). "British Peace Aims and the Eastern Question: The Political Intelligence Department and the Eastern Committee, 1918". Middle Eastern Studies. 23 (4): 419–436.

- Dockrill; Steiner (2010). "The Foreign Office at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919". The International History Review. 2 (1): 55–86.

- Prott, Volker (2016). The Politics of Self-Determination:Remaking Territories and National Identities in Europe,1917-1923. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191083549.

Additional References

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ Spencer C. Tucker; Priscilla Roberts (12 May 2008). The Encyclopedia of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: A Political, Social, and Military History [4 volumes]: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 672. ISBN 978-1-85109-842-2.

- 1 2 Huneidi 2001, p. 65.

- ↑ Antonius, 1938, p.180: "In actual fact, the terms of the McMahon Correspondence are known all over the Arab world. Extracts have from time to time been officially published in Mecca by the Sharif Husain himself, and several of the notes have appeared verbatim and in full in Arabic books and newspapers. It is open to any person with a knowledge of Arabic, who can obtain access to the files of defunct Arabic newspapers, to piece the whole of the McMahon notes together; and that work I have done in four years of travel and research, from Cairo to Baghdad and from Aleppo to Jedda."

- ↑ Report Of The Palestine Royal Commission, Chap. II.1, pp. 16–22.

- ↑ Antonius, 1938, p.169

- ↑ "1938-39 Cmd.5974 Report of Committee set up to consider certain correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sherif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 (McMahon Correspondence)" (PDF).

- ↑ Hurewitz 1979, p. 46.

- ↑ Yesilyurt, Nuri (2006). "Turning Point of Turkish Arab Relations:A Case Study on the Hijaz Revolt" (PDF). The Turkish Yearbook. XXXVII: 107–8.

- ↑ "IBS No. 94 - Jordan (JO) & Syria (SY) 1969" (PDF). p. 7-8. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- 1 2 Paris 2003, p. 24.

- ↑ Biger 2004, p. 47.

- 1 2 English version quoted in "Palestine: Legal Arguments Likely to be Advanced by Arab Representatives", Memorandum by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (Lord Halifax), January 1939, UK National Archives, CAB 24/282/19, CP 19 (39)

- ↑ See UK National Archives CAB/24/214, CP 271 (30).

- 1 2 Biger 2004, p. 48.

- 1 2 Waïl S. Hassan "Lawrence, T. E." The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. David Scott Kastan. Oxford University Press 2005.

- ↑ "Arab Revolt" A Dictionary of Contemporary World History. Jan Palmowski. Oxford University Press, 2003. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Khalidi, Rashid (1991-01-01). The Origins of Arab Nationalism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231074353.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 246.

- ↑ Kattan 2009, p. 98.

- ↑ Khouri 1985.

- ↑ Friedman 2000, p. 328.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 257.

- ↑ Smith 1993, p. 53-55.

- 1 2 Huneidi 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ Friedman 2000, p. 195–197.

- ↑ Choueiri, 2000, p. 149.

- ↑ Report of a Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sharif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 Archived 30 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine., UNISPAL, Annex H.

- ↑ Report of a Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sharif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 Archived 30 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine., UNISPAL, Annex I.

- ↑ Hughes, 1999, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ "DESIRES OF HEDJAZ STIR PARIS CRITICS; Arab Kingdom's Aspirations Clash with French Aims in Asia Minor. PRINCE BEFORE CONFERENCE Feisal's Presentation of His Case will Probably Be Referred to a Special Committee. England Suggested as Mandatory.".

- ↑ Paris 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ "Faisal I" A Dictionary of World History. Oxford University Press, 2000.

- ↑ Federal Research Division, 2004, p. 41.

- ↑ Milton-Edwards, 2006, p. 57.

- ↑ Project Gutenberg: The Peace Negotiations by Robert Lansing, Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1921, Chapter XIII 'THE SYSTEM OF MANDATES'

If the advocates of the system intended to avoid through its operation the appearance of taking enemy territory as the spoils of war, it was a subterfuge which deceived no one. It seemed obvious from the very first that the Powers, which under the old practice would have obtained sovereignty over certain conquered territories, would not be denied mandates over those territories. The League of Nations might reserve in the mandate a right of supervision of administration and even of revocation of authority, but that right would be nominal and of little, if any, real value provided the mandatory was one of the Great Powers as it undoubtedly would be. The almost irresistible conclusion is that the protagonists of the theory saw in it a means of clothing the League of Nations with an apparent usefulness which justified the League by making it the guardian of uncivilized and semi-civilized peoples and the international agent to watch over and prevent any deviation from the principle of equality in the commercial and industrial development of the mandated territories.

It may appear surprising that the Great Powers so readily gave their support to the new method of obtaining an apparently limited control over the conquered territories, and did not seek to obtain complete sovereignty over them. It is not necessary to look far for a sufficient and very practical reason. If the colonial possessions of Germany had, under the old practice, been divided among the victorious Powers and been ceded to them directly in full sovereignty, Germany might justly have asked that the value of such territorial cessions be applied on any war indemnities to which the Powers were entitled. On the other hand, the League of Nations in the distribution of mandates would presumably do so in the interests of the inhabitants of the colonies and the mandates would be accepted by the Powers as a duty and not to obtain new possessions. Thus under the mandatory system Germany lost her territorial assets, which might have greatly reduced her financial debt to the Allies, while the latter obtained the German colonial possessions without the loss of any of their claims for indemnity. In actual operation the apparent altruism of the mandatory system worked in favor of the selfish and material interests of the Powers which accepted the mandates. And the same may be said of the dismemberment of Turkey. It should not be a matter of surprise, therefore, that the President found little opposition to the adoption of his theory, or, to be more accurate, of the Smuts theory, on the part of the European statesmen.

- ↑ "MidEast Web - Feisal-Weizmann Agreement". www.mideastweb.org.

- ↑ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Ten: minutes of meetings February 15 to June 17, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ↑ Biger 2004, p. 173.

- ↑ "Lawrence, Thomas Edward, 'Lawrence of Arabia'" A Dictionary of Contemporary World History. Jan Palmowski. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ↑ Kalisman 2016, p. 67.

- ↑ Storrs 1937, p. 168.

- ↑ "1938-39 Cmd.5974 Report of Committee set up to consider certain correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sherif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 (McMahon Correspondence)" (PDF). p. Para 5.

- ↑ Toynbee & Friedman 1970, p. 185-201.

- 1 2 Rea, Tony; Wright, John (2 June 1997). "The Arab-Israeli Conflict". Oxford University Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Schneer 2010, p. 66-67.

- ↑ Barr, 2011 & Ch.2,9.

- ↑ Report of a Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sharif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 Archived 30 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine., UNISPAL, Annex A, paragraph 19: "The contention that the British Government did intend Palestine to be removed from the sphere of French influence and to be included within the area of Arab independence (that is to say, within the area of future British influence) is also borne out by the measures they took in Palestine during the War. They dropped proclamations by the thousand in all parts of Palestine, which bore a message from the Sharif Husain on one side and a message from the British Command on the other, to the effect that an Anglo-Arab agreement had been arrived at securing the independence of the Arabs, and to ask the Arab population of Palestine to look upon the advancing British Army as allies and liberators and give them every assistance. Under the aegis of the British military authorities, recruiting offices were opened in Palestine to recruit volunteers for the forces of the Arab Revolt. Throughout 1916 and the greater part of 1917, the attitude of the military and political officers of the British Army was clearly based on the understanding that Palestine was destined to form part of the Arab territory which was to be constituted after the War on the basis of independent Arab governments in close alliance with Great Britain."

- 1 2 3 Peace conference: memoranda respecting Syria, Arabia and Palestine, IOR/L/PS/11/147, PRO CAB 29/2

- ↑ Political Intelligence Dept. Foreign office. "British Commitments to King Husein CAB 24/68/86". The National Archives.

- ↑ Political Intelligence Dept. Foreign office. "The Settlement of Turkey and the Arablan Peninsula CAB 24/72/6". The National Archives.

- ↑ Political Intelligence Dept. Foreign office. "Maps illustrating the Settlement of Turkey and the Arabian Peninsula CAB 24/72/7". The National Archives.

- ↑ "Minutes of meetings 1-49 CAB 27/24". The National Archives. p. 148-52.

- ↑ Toynbee 1970, p. 185-6.

- ↑ Goldstein 1987, p. 423.

- ↑ Dockrill, Steiner 1987, p. 58.

- ↑ Prott 2016, p. 35.

- ↑ "NO PEACE BASIS YET, BALFOUR ASSERTS; Answers Pacifist in Commons That Berlin Still Aims at World Domination. AND NOT REASONABLE PEACE Britain and America United on War Aims--Secretary Defends Secret Treaties. Germany Seeking Domination. Belleves Russia Will Recover. No Temporary Peace Wanted.".

- ↑ Zachary Lockman "Balfour Declaration" The Oxford Companion to the Politics of the World, 2e. Joel Krieger, ed. Oxford University Press Inc. 2001.

- ↑ "Palestine: Legal Arguments likely to be advanced by Arab Representatives CAB 24/282/19". The National Archives.

- ↑ Report of a Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sharif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 Archived 24 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine., UNISPAL, Annex C.

- ↑ "Palestine Constitution". Hansard.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 98-99.

- ↑ Toynbee & Friedman 1970, p. 188.

- ↑ Letter to the Editor, J. S. F. Parker, Department of History, University of York, 2 April 1976, Page 17

- ↑ Mousa, Suleiman (1993), "Sharif Husayn and Developments Leading to the Arab Revolt", New Arabian Studies, University of Exeter Press, I: 49–, ISBN 978-0-85989-408-1

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 203a: FO 371/2768, 80305/938, McMahon's despatch no. 83, Cairo, 19 Apr 1916

- ↑ Friedman 2000, p. 292.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 203.

- 1 2 Toynbee & Friedman 1970, p. 191.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 206a: Cab 17/176 "The Arab question"

- ↑ Friedman 2000, p. 292a: FO 371/6237 (1921), file 28 E(4), volume 1, pages 110-12

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 206b.

- ↑ Toynbee & Friedman 1970, p. 187.

- 1 2 John Quigley (6 September 2010). The Statehood of Palestine: International Law in the Middle East Conflict. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-139-49124-2.

- ↑ National Archives, CAB 24/68/86, British Commitments to King Husein, Political Intelligence Department, Foreign Office, November 1918

- ↑ ‘Memorandum on British commitments to King Hussein’. Peace Congress file, 15 March 1919. The National Archives, London. Ref: FO 608/92.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 210.

- ↑ Toynbee & Friedman 1970, p. 193.

- ↑ National Archives, CAB 24/72/6, The Settlement of Turkey and the Arablan Peninsula, British Commitments to King Husein, Political Intelligence Department, Foreign Office, 21 November 1918

- ↑ Ingrams p40

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 211.

- 1 2 Walter Reid (1 September 2011). Empire of Sand: How Britain Made the Middle East. Birlinn. pp. 71–75. ISBN 978-0-85790-080-7.

- ↑ Palestine Papers 1917–1922, Doreen Ingrams, page 48 and UK Archives PRO. CAB 27/24.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 216-217.

- ↑ Rachel Havrelock (27 October 2011). River Jordan: The Mythology of a Dividing Line. University of Chicago Press. pp. 231–. ISBN 978-0-226-31959-9.

- ↑ Memorandum by Mr. Balfour (Paris) respecting Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia, 132187/2117/44A, August 11, 1919

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 220.

- ↑ Allawi, Ali A. (11 March 2014), Faisal I of Iraq, Yale University Press, pp. 309–, ISBN 978-0-300-12732-4

- ↑ Friedman 2000, p. 294: F.O. 371/5066, E. 14959/9/44, "Memorandum on Palestine Negotiations with the Hedjaz," by H[ubert] W. Y[oung], dated 29 November 1920

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 246a: "...the untruth that the government had 'always' regarded McMahon's reservation as covering the vilayet of Beirut and the sanjaq of Jerusalem, since in fact this argument was no older than Young's memorandum of November 1920"

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 297.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 316: wrote that Lawrence's "accusation that the British had acted in bad faith has been given a very wide currency not only by his writings, but also by Terence Rattigan's play Ross, and the Panavision technicolor film Lawrence of Arabia".

- ↑ Mangold, Peter (30 April 2016). What the British Did: Two Centuries in the Middle East. I.B.Tauris.

- ↑ Toynbee & Friedman 1970, p. 199.

- ↑ "Palestine"; Commons Questions 11 July 1922

- ↑ National Archives CAB 24/159/6 17 February 1923

- ↑ Bennett 1995, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 House of Lords debate, HL Deb 27 March 1923 vol 53 cc639-69

- ↑ Report of a Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sharif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 Archived 24 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine., UNISPAL, enclosure to Annex A.

- 1 2 3 Jeffries, Joseph Mary Nagle (1939). Palestine: The Reality. Longmans, Green and Company. p. 105.

- ↑ "Palestine Mandate"

- 1 2 House of Lords debate, HL Deb 20 July 1937 vol 106 cc599-665, Viscount Samuel: "Speaking to him of Lord Grey's speech, I said I wished to write to him on the subject, and he said he could tell me facts that I could communicate to Lord Grey. He gave me, quite unofficially, this note dated April 12, 1923"

- ↑ Reid, Walter (1 September 2011). Empire of Sand: How Britain Made the Middle East. Birlinn. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-0-85790-080-7.

- ↑ Wilson 1990, p. 601-2.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 258-9.

- ↑ [Cab.24/214, C.P. 271(30) http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/large/cab-24-214.pdf]

- ↑ "Palestine (McMahon Correspondence)"

- ↑ Friedman 2000, p. 292b: FO 371/14495 (1930)

- ↑ Toynbee & Friedman 1970, p. 192.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 254.

- 1 2 Kedouri 2014, p. 263.

- ↑ Kedouri 2014, p. 262.

- ↑ Rush, Alan (30 June 1995). Records of the Hashimite dynasties: a twentieth century documentary history. Archive Editions. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-85207-590-3.

- ↑ "1938-39 Cmd.5974 Report of Committee set up to consider certain correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sherif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 (McMahon Correspondence)" (PDF).

- ↑ Report of a Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sharif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 Archived 24 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine., UNISPAL.

- ↑ Hadawi, Sami (1991). Bitter Harvest: A Modern History of Palestine. Olive Branch Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-940793-81-1.

- ↑ See UK National Archives CAB/24/143, Eastern Report, No. XVIII, 31 May 1917.

- ↑ Toynbee, Arnold (1970). "The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence: Comments and a Reply". Journal of Contemporary History. 5 (4): 185–201.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Hussein-McMahon Correspondence at the Jewish Virtual Library.

- The 1937 Peel Commission on the McMahon correspondence and the "Arab Revolt"