McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II in UK service

The United Kingdom operated the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II as one of its principal combat aircraft from the 1960s to the early 1990s. The UK was the first export customer for the Phantom, which was ordered in the context of political and economic difficulties around British designs for the roles that it eventually undertook. The Phantom was procured to serve in both the Fleet Air Arm and Royal Air Force in several roles including air defence, close air support, low-level strike and tactical reconnaissance.

Although assembled in the United States, the UK's Phantoms were a special batch built separately and containing a significant amount of British technology as a means of easing the pressure on the domestic aerospace industry in the wake of major project cancellations.[1] Two variants were initially built for the UK: the F-4K variant was designed from the outset as an air defence interceptor to be operated by the Fleet Air Arm from the Royal Navy's aircraft carriers; the F-4M version was procured for the RAF to serve in the tactical strike and reconnaissance roles. In the mid-1980s, a third Phantom variant was obtained when a quantity of second-hand F-4J aircraft were purchased to augment the UK's air defences following the Falklands War.

The Phantom entered service with both the Fleet Air Arm and the RAF in 1969. In the Royal Navy it had a secondary strike role in addition to its primary use for fleet air defence, while in the RAF it was soon replaced in the strike role by other aircraft designed specifically for strike and close air support. By the mid-1970s it had become the UK's principal interceptor, a role in which it continued until the late 1980s.

Background

In the late 1950s, the British Government began the process of replacing its early second-generation jet combat aircraft in service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Fleet Air Arm (FAA). At the time, the British aerospace industry was still a major source of equipment, and designs from several companies were in service. The 1957 Defence White Paper brought about a significant change in the working practices, the Government compelling major aerospace manufacturers to amalgamate into two large groups: British Aircraft Corporation (formed from the merger of English Electric, Vickers-Armstrongs, Bristol and Hunting) and Hawker Siddeley (formed from the merger of Hawker Siddeley Aviation, Folland, de Havilland and Blackburn).[2]

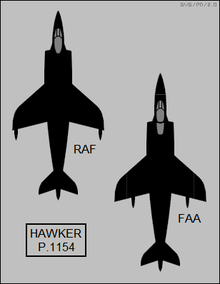

The intention was to rationalise the industry to cut costs, and the government offered incentives for amalgamation through promises of contracts for new aircraft orders for the armed forces. At the time, the RAF were looking to replace the English Electric Canberra light bomber in the long-range interdictor role, and the Hawker Hunter in the close air support role, while the Royal Navy sought an aircraft to assume the fleet air defence role from the de Havilland Sea Vixen. BAC, through its English Electric subsidiary, had begun developing a new high-performance strike aircraft, the TSR-2,[3] which was intended for long-range, low-level strike missions with conventional and tactical nuclear weapons, as well as tactical reconnaissance. Hawker Siddeley was also developing a new aircraft, based on its P.1127 V/STOL demonstrator. The P.1154 was proposed as a supersonic version that could be marketed to both the RAF and Royal Navy to fulfil a number of roles: close air support, air superiority and fleet air defence.[4]

During the early 1960s, aircraft development became increasingly expensive, resulting in major projects often becoming mired in political and economic concerns. The development of TSR-2 saw increasing cost overruns, combined with the presence of a potentially cheaper alternative then under development in the United States, the F-111.[5] The P.1154 was subject to the ongoing inter-service rivalry between the Royal Navy and RAF, which led to two wildly differing specifications being submitted for the aircraft that were impossible to fulfill with a single airframe.[6]

%2C_Ark_Royal_(R09)_and_Hermes_(R12)_underway_c1961.jpg)

In 1964, the Royal Navy withdrew from the P.1154 project, and moved to procure a new fleet air defence interceptor. It eventually selected the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, then in service with the US Navy as its primary air defence aircraft, intended to be operated from both existing and planned aircraft carriers.[7] This better suited the Royal Navy, as the Phantom had two engines (providing redundancy in the event of an engine failure), was cheaper than the P.1154, and was immediately available.[8] The P.1154 was thus left as a wholly RAF project. Later the same year, a general election brought the Labour Party back into power. The new government undertook a defence review, which led to the 1966 Defence White Paper that cancelled several projects, including both the P.1154 and TSR-2. As a consequence, the government was forced to order new aircraft to replace the Canberra and Hunter for the RAF, and eventually chose two types. To replace the Canberra in the long-range role (which was intended for TSR-2), the F-111 was selected, with plans for a redesigned variant, while the roles undertaken by the Hunter (for which P.1154 was to be procured) would be undertaken by a further purchase of F-4 Phantoms. As the Phantom had been developed primarily for fleet air defence, the Royal Navy was happy with the choice of the aircraft as its Sea Vixen replacement, given that the type had been operational in that role with the US Navy since 1961, whilst US aircraft had successfully undertaken touch-and-go landings on both HMS Hermes and HMS Victorious.[9][10][11] The RAF was less enthusiastic, as the Phantom was primarily designed to operate in the air defence rather than the close air support role, and had been selected as its Hunter replacement more as a way of decreasing the per-unit cost of the overall UK order.[12][13]

Partly as a means of guaranteeing employment in the British aerospace industry, agreement was reached that major portions of the UK's Phantoms would be built domestically.[1] The F-4J variant, which was then the primary version in service with the US Navy, was taken as the basis for the UK aircraft, subject to major redesign. The most significant change was the substitution of the larger and more powerful Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan for the GE J79 turbojet to allow operations from the Royal Navy's carriers. Although several had received major upgrades, all of the UK carriers were smaller than the US carriers from which the J79-GE-8 and −10 powered Phantoms operated.[14] To accommodate the larger engines, BAC redesigned and built the entire rear fuselage section. The Westinghouse AN/AWG-10 radar carried by the F-4J was to be procured and built under licence by Ferranti as the AN/AWG-11 for FAA aircraft and AN/AWG-12 for those of the RAF.[8][15] The changes to the aircraft led to the two variants being given their own separate series letters, with the FAA version being designated as the F-4K and the RAF version as the F-4M.[16]

Initially, there was an intention to procure up to 400 aircraft for the Royal Navy and the RAF, but the development cost for the changes to accommodate the Spey turbofans meant that the per-unit price eventually ended up three times the price of an F-4J. Because the government then had a policy of negotiating fixed-price contracts, these costs could not be evened out by a large production run, which left the total order at 170.[17]

Variants

Prototypes

The British Government ordered a total of four prototypes (two F-4K and two F-4M), together with a pair of pre-production F-4K aircraft. The first UK Phantom, a prototype F-4K (designated YF-4K), first flew on 27 June 1966 at the McDonnell Douglas plant in St. Louis. The second made its first flight on 30 August 1966. The two pre-production F-4K aircraft were constructed alongside the prototypes, and were initially used for fit check trials of the various systems to be fitted – the first was used for catapult/arrestor and deck landing trials, and the second was primarily for testing the radar and missile systems. All four were delivered to the UK from 1969 to 1970 for continued test work by both the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment and British Aerospace. One of the pre-production examples was subsequently delivered to the RAF for operational use, but was lost in 1978.[18] The first F-4M prototype (designated YF-4M) first flew on 17 February 1967, and was also used for fit checks before delivery to the UK.[19]

Operators

|

|

|

F-4K Phantom FG.1

| F-4K Phantom FG.1 | |

|---|---|

_1972.jpg) | |

| A Royal Navy Phantom FG.1 of 892 NAS aboard HMS Ark Royal in 1972 | |

| Role | Fleet air defence fighter Air defence interceptor |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas |

| First flight | 27 June 1966 |

| Introduction | 30 April 1968 (FAA) 1 September 1969 (RAF) |

| Retired | 27 November 1978 (FAA) 30 January 1990 (RAF) |

| Status | Withdrawn |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force Fleet Air Arm |

| Produced | 1966–69 |

| Number built | 48 |

| Career | |

| Serial | XT595 – XT598[20] XT857 – XT876[20] XV565 – XV592[21] XV604 – XV610 (cancelled)[21] |

Royal Navy

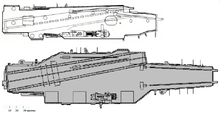

In 1964, 140 new-build Phantoms were ordered for the Fleet Air Arm to serve as the Royal Navy's primary fleet air defence aircraft, with a secondary strike capability. These were procured to replace the Sea Vixen then in service in the role, with the intention that they operate from the decks of four brand new or modernised aircraft carriers.[22] At the time, the Royal Navy's carrier force consisted of five fleet or light fleet carriers of differing sizes and ages.[23] Of the five in service, only Eagle and Ark Royal, each displacing approximately 50,000 tons, were big enough to accommodate the Phantom in sufficient numbers,[lower-roman 1] so plans were put in place to rebuild the two ships to enable the operation of the aircraft.[lower-roman 2]

| Ship | Displacement | Length | Beam | Number of aircraft | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ark Royal | 53,000 long tons (54,000 t) | 803.5 ft (244.9 m) | 171 ft (52 m) | 50 | |

| Eagle | 54,100 long tons (55,000 t) | 811.5 ft (247.3 m) | 171 ft (52 m) | 45 | Major reconstruction 1959-64 |

| Victorious | 35,500 long tons (36,100 t) | 781 ft (238 m) | 157 ft (48 m) | 36 | Major reconstruction 1950-58 to allow operation of modern aircraft |

| Hermes | 28,700 long tons (29,200 t) | 744 ft (227 m) | 144.5 ft (44.0 m) | 28 | |

| Centaur | 27,000 long tons (27,000 t) | 737 ft (225 m) | 123 ft (37 m) | 26 | Used primarily during absence of other ships due to reconstruction |

| Length | Wingspan | Height | Max. take-off weight | Engines | Thrust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea Vixen | 53 ft 6.5 in (16.320 m) | 50 ft 0 in (15.24 m) | 10 ft 9 in (3.28 m) | 46,750 lb (21,210 kg) | 2 x Rolls-Royce Avon Mk.208 | 11,000 lbf (49 kN)(each engine) |

| Phantom | 57 ft 7 in (17.55 m) | 38 ft 4 in (11.68 m) | 16 ft 1 in (4.90 m) | 56,000 lb (25,000 kg) | 2 x Rolls-Royce Spey Mk.203 | 12,140 lbf (54.0 kN) (dry thrust) |

| 20,515 lbf (91.26 kN) (with afterburner) |

_in_1963.jpg)

_1970.jpg)

At the same time, two new aircraft carriers were planned. The requirements for the intended force of four carriers meant that five squadrons of Phantoms would be needed.[17] However, in its 1966 Defence White Paper, the Government decided to cancel the two new carriers, which led to reductions in the total order for the Royal Navy's Phantoms. Initially 143 were ordered, which was cut to 110, and finally just 50, with options for another seven.[31] The intention was to form a pair of front-line squadrons, each of twelve aircraft, that would operate from the two remaining, heavily modernised fleet carriers. The rest of the aircraft would be a reserve and for training.[8][22]

The Royal Navy received its first F-4K Phantoms, which carried the British designation FG.1, in April 1968.[8] These were assigned to 700P Naval Air Squadron (NAS), which was to serve as the Intensive Flying Trials Unit. Upon completion of the successful flight trials, 767 Naval Air Squadron was commissioned in January 1969 as the FAA's training squadron. This was followed at the end of March 1969 by 892 Naval Air Squadron, which was commissioned as the Royal Navy's first operational Phantom unit, intended to embark in Ark Royal once her three-year refit had completed in 1970.[32]

At the same time as the Fleet Air Arm was receiving its first aircraft, the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment had three FG.1s delivered to its 'C' Squadron for flight deck trials aboard Eagle. Two sets of trials were successfully carried out in March and June 1969; the first comprised approaches and touch and go landings,[33] while the second set of trials involved full catapult launch and arrested recovery.[34] As a result of the reheat from the Spey turbofans, the ship's jet blast deflectors (JBD) were not used; instead a steel plate was fixed to the deck to absorb the heat of the engines building to launch, and fire hoses were used after each launch to prevent them melting.[35]

%2C_November_1975.jpg)

Ark Royal had entered refit to accommodate the Phantom in 1967; this involved a major reconstruction, including several elements to allow the ship to operate the aircraft – the flight deck was increased in area and fully angled to 8½°, the arresting gear was replaced with a new water-spray system[36] to accommodate the Phantom's higher weight and landing speed, and bridle catchers[lower-roman 3] and water-cooled JBDs[lower-roman 4] were fitted to the catapults.[37] Once this work was complete, Eagle was scheduled to undergo a similar modernization. In 1969, the planned refit of Eagle was cancelled, and the options for seven additional FG.1s was not taken up.[31][35] As a consequence, it was decided to further reduce the FAA's Phantom fleet to just 28 aircraft. The remaining 20 aircraft were then allocated to the Royal Air Force.[8]

In 1970, Ark Royal embarked 892 NAS as part of her air group for the first time, with a total of 12 aircraft. The first operational use of the Royal Navy's Phantoms had come in 1969, when 892 NAS had embarked for training with the US aircraft carrier USS Saratoga in the Mediterranean, and had undertaken air defence missions alongside the ship's own F-4Js.[38] This deployment showed the necessity for the modifications fitted to Ark Royal, as the heat from the afterburners of the Spey, combined with the increased angle of attack resulting from the extendable nosewheel, during the initial launches from Saratoga caused the deck plates to distort, leading to subsequent catapult launches being undertaken at reduced weight without the use of re-heat.[26] During Ark Royal's first three-year commission, 892 NAS, which had initially used RNAS Yeovilton in Somerset as its home base, moved to RAF Leuchars in Fife where, during the periods when it was not embarked, it undertook Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) duties alongside the RAF's 43 Squadron. The Phantom served in the Fleet Air Arm until 1978, when Ark Royal was finally withdrawn from service, leaving no ship in the Royal Navy capable of operating the type. The final catapult launch from Ark Royal was a Phantom of 892 NAS on 27 November 1978 during the disembarkation of the air group following the ship's final deployment; the squadron's aircraft were delivered to RAF St Athan in Wales, where they were handed over to the RAF.[39] During the type's service with the Royal Navy, 10 of the total FAA fleet of 28 were lost in crashes.[40]

Royal Air Force

Following the cancellation of the planned refit of HMS Eagle to allow her to operate the Phantom, a total of 20 airframes that had originally been ordered for the Fleet Air Arm were diverted to the Royal Air Force to serve in the air defence role.[41] At the time, the RAF's primary interceptor was the English Electric Lightning, which suffered badly both in terms of range, loiter time and weapons fit, all of which hampered its effectiveness, especially in long interceptions of Soviet Air Forces and Soviet Naval Aviation bombers and reconnaissance aircraft over the North Sea and North Atlantic. So a new Phantom squadron was formed at RAF Leuchars,[42] the UK's most northerly air defence base at the time, to take advantage of the improvements that the Phantom provided over the Lightning – it could carry more fuel, and could thus fly further for longer; it was fitted with a more powerful radar; and it could carry more missiles (up to 8, compared to 2 for the Lightning). On 1 September 1969, 43 Squadron was formed at Leuchars, operating as part of the UK's northern QRA zone alongside the Lightnings of 11 Squadron and, from 1972, the Royal Navy Phantoms of 892 Naval Air Squadron.[43]

| Aircraft | Powerplant | Speed (at 40,000 ft) | Ceiling | Range | Fuel capacity | Armament | Avionics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combat | Maximum | ||||||||

| Lightning | 2 x Rolls-Royce Avon 301 turbojets | 1,500 mph | 60,000 ft | 800 m | 1,250 m | 3,200 litres (internal) 2,430 litres (ventral tank) 2,400 litres (2 x external overwing tanks) |

2 x Firestreak or Red Top AAMs 2 x 30mm ADEN cannon |

Ferranti AI.23 X-band monopulse radar | [44] |

| Phantom | 2 x Rolls-Royce Spey 203 turbofans | 1,386 mph | 57,200 ft | 1,000 m | 1,750 m | 7,550 litres (internal) 7,600 litres (external tanks) |

4 x AIM-7 Sparrow or Skyflash AAMs 4 x AIM-9 Sidewinder AAMs 20mm M61 Vulcan cannon |

Ferranti AN/AWG-11 X-band multi-mode radar | [8] |

Upon the withdrawal of HMS Ark Royal in 1978, the Phantoms of the Fleet Air Arm were turned over to the RAF and used to form a second squadron at Leuchars. At the time, 111 Squadron was stationed there operating the FGR.2 version of the Phantom, having been there since 1975.[45] In 1979, to save costs resulting from the differences between the FG.1 and FGR.2, the squadron converted to the ex-Navy aircraft and the FGR.2 airframes were distributed to other Phantom units. Both 43 and 111 Squadrons retained the FG.1 until 1989, when they converted to the new Tornado F.3. Following the standing down of the two operational squadrons and the final withdrawal of the type from service, the bulk of the RAF's FG.1 Phantoms were scrapped.[46][47][48] The RAF lost eight of their FG.1s in crashes throughout the type's twenty year service.[40]

Operators

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment

Royal Navy

Royal Navy

- 700P Naval Air Squadron

- 767 Naval Air Squadron

- 892 Naval Air Squadron

Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

- No. 43 Squadron

- No. 64 (R) Squadron

- No. 111 Squadron

Gallery (FG.1)

_1975.jpg) Phantom FG.1 of 892 NAS lands on USS Nimitz in 1975

Phantom FG.1 of 892 NAS lands on USS Nimitz in 1975

Phantom FG.1 of 111 Squadron at RAF Greenham Common in July 1983

Phantom FG.1 of 111 Squadron at RAF Greenham Common in July 1983

F-4M Phantom FGR.2

| F-4M Phantom FGR.2 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Royal Air Force Phantom FGR.2 of 23 Squadron at RAF Finningley in 1977 | |

| Role | Air defence interceptor Low level strike Close air support |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas |

| First flight | 17 February 1967 |

| Introduction | 23 August 1968 |

| Retired | 1 November 1992 |

| Status | Withdrawn |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force |

| Produced | 1966–69 |

| Number built | 118 |

| Career | |

| Serial | XT852 – XT853[20] XT891 – XT914[20] XV393 – XV442[21] XV460 – XV501[21] XV520 – XV551 (cancelled)[21] |

Close air support

Following the cancellation of both the TSR-2 and P.1154 programmes, the RAF were still left with a requirement to replace both the Canberra and Hunter in the long-range strike, close air support and reconnaissance roles. This resulted in the procurement of two aircraft, the General Dynamics F-111K, intended for the long-range interdiction roles carried out by the Canberra, and the F-4M Phantom, which would be used in the close air support role undertaken by the Hunter. The F-111K was cancelled within a year of being ordered, but the order for 150 Phantoms went ahead alongside the Phantom order for the Royal Navy; the final 32 units of the RAF order were eventually cancelled.[49] The RAF Phantom, given the designation FGR.2, was broadly similar to the naval version, with some minor variations in terms of engines, avionics and structure, which related to its use as a land-based, rather than carrier-based aircraft.[8]

The first RAF Phantom unit was 228 Operational Conversion Unit, which was stood up in August 1968. The Phantom entered operational service in May 1969, when 6 Squadron was formed at RAF Coningsby in the tactical strike role. 54 Squadron was formed in September the same year, followed by 41 Squadron in 1972 as a tactical reconnaissance unit. A further four squadrons were formed under RAF Germany in 1970 and 1971: 2, 14, 17 and 31 Squadrons, all at RAF Brüggen.[8] Along with their conventional strike role, 14, 17 and 31 Squadrons were assigned a tactical nuclear strike role under SACEUR, using weapons supplied by the United States.[50][51] After initial work-up, 2 Squadron moved to and operated from RAF Laarbruch in the tactical reconnaissance role. The aircraft assigned to the two tactical reconnaissance units were fitted with a pod containing four optical cameras, an infrared linescan and a sideways looking radar.[8][52]

During the 1970s, UK and France were developing a new aircraft which could fill the RAF tactical strike and reconnaissance missions: the SEPECAT Jaguar was introduced into service in 1974, and led to a re-think of the Phantom's role as, at the same time, the limitations of the Lightning as an interceptor were becoming more apparent. The conversion of the RAF's FGR.2 squadrons to operate the Jaguar, combined with its use of the Blackburn Buccaneer, meant that it was possible to begin transferring Phantoms to operate purely as interceptors in the air defence role.[8]

Air defence

In October 1974, 111 Squadron converted from the Lightning to the Phantom FGR.2, becoming the first unit to operate the type in the air defence role (notwithstanding 43 Squadron, which had used the FG.1 version since 1969). As more Jaguars were delivered, more Phantoms were released enabling existing Lightning squadrons to be converted;[53] 19 Squadron and 92 Squadron, the forward deployed air defence units in Germany, converted in 1976 and 1977 respectively, at the same time moving from RAF Gütersloh, which was the closest RAF base to the East German border, to RAF Wildenrath, taking advantage of the Phantom's superior range over the Lightning.[17] Three further UK based squadrons, 23, 29 and 56, were also converted between 1974 and 1976.[17] 111 Squadron, which had been the first unit to use the FGR.2 as an interceptor, converted to the FG.1 version in 1979 following the transfer of the Royal Navy's remaining airframes to the RAF.[8] The Phantom subsequently served as the RAF's primary interceptor for over a decade until the introduction into service of the Panavia Tornado F.3 in 1987.[54][55][56]

When Phantoms were first delivered to interceptor squadrons, they remained in the grey-green camouflage colour scheme more associated with the strike and close air support missions they had undertaken. During the late 1970s, the RAF began experimenting with new colours for its air defence units, with 56 Squadron tasked with trialling proposed new schemes. In October 1978, a Phantom FGR.2 of 56 Squadron became the first to be painted in the new air superiority grey colour, combined with small, low visibility roundels and markings. However, although the roundel remained in low visibility colours, individual squadron markings eventually returned to more observable sizes and colours.[57]

In May 1982, three Phantoms from 29 Squadron were forward deployed to RAF Wideawake on Ascension Island to provide air cover for the RAF's operations during the Falklands War, replacing Harriers of 1 Squadron, which were transiting to the war zone.[58] In August 1982, following the end of the conflict and the reconstruction of the runway, 29 Squadron detached a number of its aircraft to RAF Stanley to provide air defence for the Falkland Islands.[59] Late the following year, 23 Squadron took up the role, remaining stationed there until October 1988, when they were replaced by 1435 Flight. To make up for the loss of an entire squadron from the UK Air Defence Region, the RAF procured 15 second-hand F-4J Phantoms that had previously been used by the US Navy. These aircraft were operated by 74 Squadron from 1984 until 1991, when they were replaced by FGR.2 Phantoms that had been released by other squadrons following their conversion to the Tornado.[60] Initially, it was intended that Phantoms and Tornados serve alongside each other. A total of 152 Tornado F.3s were ordered for the RAF, enough to convert four squadrons of Phantoms and two of Lightnings, but insufficient to completely convert every air defence squadron. Both 23 and 29 Squadrons converted from the Phantom FGR.2 to the Tornado between 1987 and 1988, alongside the conversion of the final two remaining Lightning squadrons. The intention was to retain a pair of UK based Phantom squadrons at RAF Wattisham, alongside a pair of Tornado units at RAF Coningsby to provide air defence cover for the southern half of the UK Air Defence Region.[61] Another two squadrons stationed in Germany would also be retained.[62][63] The end of the Cold War however led to a more rapid withdrawal of Phantom units than had originally been planned; under the Options for Change defence review the Phantom was to be withdrawn from service, with the two Germany based units disbanded as part of the gradual run down of the RAF's presence, and a reduction in the number of air defence squadrons leading to the two UK based units being disbanded in late 1992.[64] However, just prior to the final withdrawal of the Phantom, it was recalled operationally as a result of Operation Granby, the UK's participation in the First Gulf War, when a total of six aircraft from 19 and 92 Squadrons were forward deployed to provide air defence cover at RAF Akrotiri; this was to replace the Tornados that had been originally deployed there on exercise, and were subsequently sent to the Gulf region.[65] Following their final withdrawal from service, with a few exceptions, the bulk of the RAF's FGR.2 fleet was scrapped.[47][48] Over its service life, 37 FGR.2s were lost to crashes.[40]

Operators

|

|

Gallery (FGR.2)

Phantom FGR.2 of 228 OCU at NAS Patuxent River in 1970

Phantom FGR.2 of 228 OCU at NAS Patuxent River in 1970 Phantom FGR.2 of 6 Squadron at RAF Coningsby in 1974

Phantom FGR.2 of 6 Squadron at RAF Coningsby in 1974 Phantom FGR.2 of 19 Squadron alongside a US Navy F-14 in 1990

Phantom FGR.2 of 19 Squadron alongside a US Navy F-14 in 1990

F-4J(UK) Phantom

| F-4J(UK) Phantom F.3 | |

|---|---|

_Phantom_of_74_Squadron_in_flight_1984.jpg) | |

| A Royal Air Force Phantom F.3 of 74 Squadron in 1984 | |

| Role | Air defence interceptor |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas |

| First flight | 10 August 1984 |

| Introduction | 19 October 1984 |

| Retired | 31 January 1991 |

| Status | Withdrawn |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force |

| Produced | 1984 |

| Number built | 15 |

| Career | |

| Serial | ZE350 – ZE364[66] |

After the Falklands War, the UK government began upgrading the defences of the Falkland Islands to guard against any further aggression from Argentina. One of the measures taken was the deployment of an interceptor squadron to the islands, with 23 Squadron forming at RAF Stanley in October 1983.[67] At the time, the air defence variant of the Panavia Tornado was still in development, meaning that the Phantom was the UK's primary air defence aircraft (supported by two remaining squadrons of Lightnings). The removal of a squadron of Phantoms to the Falkland Islands left a gap in the UK's air defences and nothing immediately available to fill it, given that the Tornado was still some years from service. As a result, the UK government decided to purchase another squadron of Phantoms. Because the aircraft in RAF service were a special production batch built to UK specifications, it would not be possible to obtain identical aircraft, so 15 second-hand airframes were procured from among the best of the ex-US Navy F-4Js stored at the Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Center at Davis–Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona and the Naval Air Rework Facility at NAS North Island.[68][69] The F-4J was chosen because it was the variant from which the RAF's F-4Ks and F-4Ms were developed, and was thus the closest available to the British aircraft. The 15 that were selected were extensively refurbished and brought to a standard almost equivalent to the F-4S, which was the last variant in service with the US Navy, the only differences being the absence of leading-edge slats and a helmet gun sight.[70]

The major difference between the F-4J and the British Phantoms was the absence of the Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan, the former being fitted with the GE J79-10B. This produced less power than the British engine, but had a faster afterburner light up, giving it better performance at high altitude, at the expense of slightly poorer acceleration at low level. The high-altitude performance was helped by the reduced drag from its smaller air intakes.[70] Initially delivered capable of carrying the AIM-7 Sparrow and AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles (AAM), they were soon made compatible with the Skyflash and SUU-23A gun pod, bringing them into line with the rest of the RAF's Phantoms.[70] Despite modifications to allow them to operate with the rest of the fleet, the F-4Js retained the vast bulk of the equipment they were originally fitted with, even requiring their crews to use American flying helmets.[17]

Although the new Phantoms were assigned a British designation as the F.3,[71][72] they were generally referred to as the F-4J(UK).[8] They were assigned to 74 Squadron at RAF Wattisham, which stood up in October 1984, two months after the first flight. The aircraft remained in service through the transition to the Tornado, which began entering service in 1987. In 1990, thanks to the conversion of F-4M squadrons to the Tornado, the RAF were able to transfer the best of its remaining FGR.2s to 74 Squadron, which meant that the F.3 was able to be withdrawn in January 1991.[60] With a couple of exceptions, all of the RAF's F-4Js were broken up for scrap.[47][48] One of the 15 airframes was lost in a crash in 1987, killing both crew members.[40]

Operators

Gallery (F.3)

A pair of Phantom F.3s form alongside a VC10 of 101 Squadron during their delivery flight to the UK in 1984

A pair of Phantom F.3s form alongside a VC10 of 101 Squadron during their delivery flight to the UK in 1984 Phantom F.3 on the flightline at RAF Valley in 1987

Phantom F.3 on the flightline at RAF Valley in 1987

Variations

FG.1 and FGR.2

The Phantom FG.1 and FGR.2 as built were similar, being fitted with broadly the same engines and avionics, although there were minor differences. The FGR.2 was fitted with the Mark 202 version of the Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan, while the FG.1 had the Mark 203; this was fundamentally the same, but the 203 had a modified control system for the afterburner, allowing it to light faster and enable power to be applied quickly in the event of a bolter on the small decks of the Royal Navy's aircraft carriers.[73] Both variants were fitted with a licence built version of the Westinghouse AN/AWG-10 avionics package; the FG.1 was fitted with the AN/AWG-11, which differed primarily in having a nose radome that was hinged and able to fold backwards against the aircraft's fuselage to allow for storage in the hangar of an aircraft carrier; the system was designed to be integrated with both the AGM-12 Bullpup missile and WE.177 as required.[15] The AN/AWG-12 fitted to the FGR.2 was not foldable, and featured a better ground mapping mode, to take into account the strike role for which the type was originally procured; allied to this was a Ferranti inertial navigation/attack system (removed when the type converted to the air defence role).[17] It was also configured to be able to control the SUU-23A gun pod, which the Royal Navy's FG.1s lacked.[15][74][75]

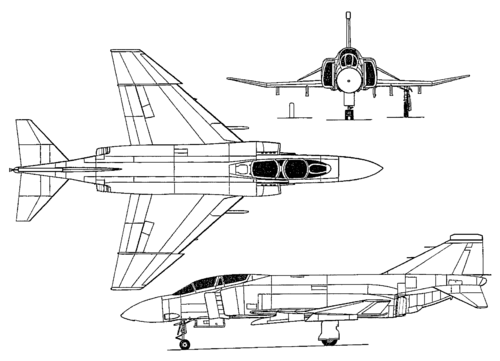

British Phantoms and other Phantoms

Although there were minor differences between the two types of Phantom built for the UK, there were many significant ones between the British Phantoms and those built for the United States. The most obvious was the substitution of the Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan for the General Electric J79 turbojet. The Spey was shorter but wider than the J79, which meant that the British Phantoms' intakes had to be redesigned for a higher airflow, making them 20% larger (with a consequent increase in drag), while the fuselage was widened by 152 mm (6.0 in). The position of the afterburner also meant that the rear of the fuselage had to be made deeper.[76] Auxiliary intake doors were fitted on the rear fuselage.[8]

Performance estimates of the Spey-engined Phantom contrary to its American equivalent indicated that the former had a 30% shorter take-off distance, 20% faster climb to altitude, higher top speed and longer range.[76] The Spey was more efficient at lower altitudes, and had better acceleration at low speed, giving British Phantoms better range and acceleration, which was shown during the deployment of 892 NAS to the Mediterranean aboard USS Saratoga in 1969, when the F-4K was repeatedly quicker off the deck than the F-4J used by the Americans.[77] It was less efficient at higher altitudes, the British Phantoms lacking speed compared to J79-powered versions owing to the increased drag of the re-designed fuselage.[15][76] This discrepancy became apparent when the F-4J was obtained by the UK in 1984; it was regarded as being the best of the three variants to serve in the RAF.[69][78]

The small size of the aircraft carriers Eagle and Ark Royal, from which the Royal Navy's Phantoms were intended to operate, compared to the US Navy carriers of the period, meant that the F-4K version required significant structural changes compared to the F-4J, from which it was descended, and which performed a similar role. As well as the folding nose radome to allow for storage in the smaller hangars of the British ships, it had to have a significantly strengthened undercarriage to account for the higher landing weight (British policy was to bring back unused ordnance). It had a telescopic nosewheel oleo that extended by 40 inches (100 cm) to provide an increased take-off attitude (the extension of the nosewheel put the Phantom at a 9° attitude[79]) due to the shorter and less powerful catapults. It was also fitted with drooping ailerons, enlarged leading edge flaps and a slotted tailplane, and increased flap and leading edge blowing, all to improve the lift and handling characteristics of operation from the much smaller carriers of the Royal Navy.[38]

| Ship | Displacement | Length | Beam | Power | Range | Speed | Aircraft catapult[80] | Complement | Total aircraft | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bow | Waist | |||||||||

| Ark Royal | 53,900 tons full load | 804 ft (245 m) | 171 ft (52 m) | 152,000 shp (113,000 kW) | 7,000 nautical miles (13,000 km) at 14 knots (26 km/h) | 31.5 knots (58.3 km/h) | 1 x 220 ft (67 m) BS5 | 1 x 268 ft (82 m) BS5A | 2,640 inc. air staff | 38 |

| 30,000 ft·lbf (41,000 J) each | ||||||||||

| Independence | 81,900 tons full load | 1,070 ft (326.1 m) | 270 ft (82.3 m) | 280,000 shp (210,000 kW) | 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km) at 20 knots (37 km/h) | 33 knots (61 km/h) | 2 x 276 ft (84 m) C-7 | 2 x 276 ft (84 m) C-7 | 5,100 inc. air staff | approx. 80 |

| 42,000 ft·lbf (57,000 J) each | ||||||||||

As the Phantom continued in service, other changes were made, most notably the Marconi ARI.18228 Radar Warning Receiver (RWR) fitted on top of the vertical stabiliser, exclusively on British models.[81] The RWR was fitted in the mid-1970s to the FG.1 and FGR.2 Phantoms, but not to the F.3. From 1978, the Skyflash AAM, derived from the AIM-7 Sparrow, began to be delivered to RAF Phantom units, and was used concurrently with the Sparrow; all three UK Phantom variants were eventually fitted to operate the Skyflash.[74]

- UK versions compared

F-4K; telescopic nosewheel oleo; hinged nose radome; wider and shorter engine exhausts; bigger air intakes; deeper rear fuselage; RWR installation on tailfin

F-4K; telescopic nosewheel oleo; hinged nose radome; wider and shorter engine exhausts; bigger air intakes; deeper rear fuselage; RWR installation on tailfin F-4J(UK); narrower and longer exhausts; narrower air intakes; shallower rear fuselage; no RWR installation

F-4J(UK); narrower and longer exhausts; narrower air intakes; shallower rear fuselage; no RWR installation

List of aircraft

The first batch of Phantoms produced for the UK received serials in the XT range, with a total of 44 production models (20 FG.1s and 24 FGR.2s), as well as the four prototypes and two pre-production models being given XT serial numbers.[20] The bulk of the UK's specially built Phantoms were delivered with XV serials (94 FGR.2s and 28 FG.1s), while the two cancelled sets of airframes (32 FGR.2 and 7 FG.1) also received XV numbers.[21] The second-hand examples (15 F.3) obtained in 1984 received serials in the ZE range.[66]

| Key: | Scrapped | Crashed | Preserved | Section preserved |

Stored | Cancelled |

|---|

| Aircraft serial | Variant | First UK operator | Final UK operator | Fate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XT595 | YF-4K | Ministry of Defence (Procurement Executive) | Scrapped | ||

| XT596 | YF-4K | Rolls-Royce | British Aerospace | Preserved (Yeovilton) | Oldest preserved UK Phantom[82] |

| XT597 | F-4K | Ministry of Defence (Procurement Executive) | Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment | Preserved (Bentwaters) | Final UK Phantom to fly[83] |

| XT598 | F-4K | Ministry of Defence (Procurement Executive) | No. 111 Squadron | Crashed, 23 Nov 1978 | Pre-production aircraft that was uprated to full production status and delivered for operations[84] |

| XT852 | YF-4M | British Aerospace | Scrapped | ||

| XT853 | YF-4M | British Aerospace | Scrapped | ||

| XT857 | F-4K | Royal Aircraft Establishment | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | Undertook deck trials on HMS Eagle[85] |

| XT858 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | British Aerospace | Scrapped | Took part in Daily Mail Trans-Atlantic Air Race[86] |

| XT859 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT860 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Crashed, 20 Apr 1988 | |

| XT861 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Crashed, 7 Sep 1987 | |

| XT862 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | 767 Naval Air Squadron | Crashed, 19 May 1971 | |

| XT863 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Cowes) |

| XT864 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Preserved (Lisburn) | |

| XT865 | F-4K | Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | Undertook deck trials on HMS Eagle[85] |

| XT866 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Crashed 9 Jul 1981 | |

| XT867 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT868 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | 892 Naval Air Squadron | Crashed, 12 May 1978 | Final Fleet Air Arm loss[40] |

| XT869 | F-4K | 700P Naval Air Squadron | 892 Naval Air Squadron | Crashed, 15 Oct 1973 | |

| XT870 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | Final aircraft launched from HMS Ark Royal[87] |

| XT871 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | Crashed 17 Jul 1973 | ||

| XT872 | F-4K | Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT873 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT874 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | Oldest F-4K not to serve in the Fleet Air Arm[88] |

| XT875 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT876 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | Crashed 10 Jan 1972 | ||

| XT891 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Preserved (Coningsby) | Gate guardian |

| XT892 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT893 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 56 Squadron | Crashed, 24 Apr 1989 | |

| XT894 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT895 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT896 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT897 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT898 | F-4M | Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment | No. 228 OCU | Scrapped | |

| XT899 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 19 Squadron | Preserved (Kbely) | |

| XT900 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 228 OCU | Scrapped | |

| XT901 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT902 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT903 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Cosford) |

| XT904 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | Crashed, 15 Oct 1971 | ||

| XT905 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Stored (Bentwaters) | |

| XT906 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT907 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Stored (Bentwaters) | |

| XT908 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 228 OCU | Crashed, 9 Jan 1989 | |

| XT909 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT910 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT911 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XT912 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 228 OCU | Crashed, 14 Apr 1982 | |

| XT913 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | Crashed, 14 Feb 1972 | ||

| XT914 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Preserved (Wattisham) | |

| XV393 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV394 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV395 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 228 OCU | Crashed, 9 Jul 1969 | First UK Phantom loss[40] |

| XV396 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV397 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 17 Squadron | Crashed, 1 Jun 1973 | |

| XV398 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV399 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Vik) |

| XV400 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV401 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Preserved (Bentwaters) | |

| XV402 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved |

| XV403 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Crashed 4 Aug 1978 | |

| XV404 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV405 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | Crashed, 24 Nov 1975 | ||

| XV406 | F-4M | Ministry of Defence | No. 228 OCU | Preserved (Carlisle) | |

| XV407 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV408 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Preserved (Tangmere) | |

| XV409 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 1435 Flight | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Stanley) |

| XV410 | F-4M | Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV411 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Stored (Manston) | Used for firefighting training |

| XV412 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV413 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 29 Squadron | Crashed, 12 Nov 1980 | |

| XV414 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 23 Squadron | Crashed, 9 Dec 1980 | |

| XV415 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Preserved (Boulmer) | Gate guardian |

| XV416 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Crashed, 3 Mar 1975 | |

| XV417 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Crashed 23 Jul 1976 | |

| XV418 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Crashed, 11 Jul 1980 | |

| XV419 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 228 OCU | Scrapped | |

| XV420 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV421 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 1435 Flight | Crashed, 30 Oct 1991 | Final UK Phantom loss[40] |

| XV422 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | Involved in 1982 Jaguar shoot-down incident[89] |

| XV423 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV424 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Preserved (Hendon) | |

| XV425 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 228 OCU | Scrapped | |

| XV426 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Norwich) |

| XV427 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 17 Squadron | Crashed, 22 Aug 1973 | |

| XV428 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 228 OCU | Crashed, 23 Sep 1988 | |

| XV429 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV430 | F-4M | No. 2 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV431 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | Crashed, 11 Oct 1974 | ||

| XV432 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV433 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV434 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 29 Squadron | Crashed, 7 Jan 1986 | |

| XV435 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV436 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 29 Squadron | Crashed, 5 Mar 1980 | |

| XV437 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Crashed, 18 Oct 1988 | |

| XV438 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV439 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV440 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | Crashed, 25 Jun 1973 | ||

| XV441 | F-4M | No. 2 Squadron | No. 14 Squadron | Crashed, 21 Nov 1974 | |

| XV442 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 1435 Flight | Scrapped | |

| XV460 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Bentwaters) |

| XV461 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 1435 Flight | Scrapped | |

| XV462 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Crashed, 8 Jan 1991 | |

| XV463 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 41 Squadron | Crashed, 17 Dec 1975 | |

| XV464 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV465 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV466 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 1435 Flight | Scrapped | |

| XV467 | F-4M | No. 2 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV468 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV469 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV470 | F-4M | No. 2 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Stored (Akrotiri) | |

| XV471 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Crashed, 3 Jul 1986 | |

| XV472 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 1435 Flight | Scrapped | |

| XV473 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV474 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Preserved (Duxford) | First Phantom in air superiority grey[90] |

| XV475 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV476 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV477 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | Crashed, 21 Nov 1972 | ||

| XV478 | F-4M | No. 41 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV479 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | Crashed, 12 Oct 1971 | ||

| XV480 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV481 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV482 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV483 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Crashed, 24 Jul 1978 | |

| XV484 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 23 Squadron | Crashed, 17 Oct 1983 | |

| XV485 | F-4M | No. 2 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV486 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 29 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV487 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV488 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV489 | F-4M | No. 2 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved |

| XV490 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Newark) |

| XV491 | F-4M | No. 31 Squadron | No. 29 Squadron | Crashed 7 July 1982 | |

| XV492 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV493 | F-4M | No. 228 OCU | No. 41 Squadron | Crashed, 9 Aug 1974 | Involved in 1974 Norfolk mid-air collision |

| XV494 | F-4M | No. 2 Squadron | No. 19 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV495 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 29 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV496 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV497 | F-4M | No. 41 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Preserved (Bentwaters) | Final RAF Phantom to fly[91] |

| XV498 | F-4M | No. 17 Squadron | No. 92 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV499 | F-4M | No. 6 Squadron | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV500 | F-4M | No. 54 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV501 | F-4M | No. 14 Squadron | No. 56 Squadron | Crashed, 2 Aug 1988 | |

| XV520-XV551 | F-4M | Cancelled | |||

| XV565 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | Crashed, 28 Jun 1971 | ||

| XV566 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | Crashed, 3 May 1970 | First Fleet Air Arm loss[40] | |

| XV567 | F-4K | Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | Undertook deck trials on HMS Eagle[85] |

| XV568 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV569 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV570 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV571 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV572 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV573 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV574 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV575 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV576 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV577 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| XV578 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Crashed, 28 Feb 1979 | |

| XV579 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV580 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | Crashed, 18 Sep 1975 | ||

| XV581 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Aberdeen) | |

| XV582 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 228 OCU | Preserved (Bruntingthorpe) | |

| XV583 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV584 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV585 | F-4K | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| XV586 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Preserved (Yeovilton) | |

| XV587 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV588 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| XV589 | F-4K | 767 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Crashed, 3 Jun 1980 | |

| XV590 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 43 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV591 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Cosford) |

| XV592 | F-4K | 892 Naval Air Squadron | No. 111 Squadron | Scrapped | |

| XV604-XV610 | F-4K | Cancelled | |||

| ZE350 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Tunbridge Wells) | |

| ZE351 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE352 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | Nose section preserved (Preston) | |

| ZE353 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE354 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE355 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE356 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE357 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE358 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Crashed, 26 Aug 1987 | ||

| ZE359 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Preserved (Duxford) | Preserved in US Navy livery[92] | |

| ZE360 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Stored (Manston) | Used for firefighting training | |

| ZE361 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE362 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE363 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

| ZE364 | F-4J(UK) | No. 74 Squadron | Scrapped | ||

Phantom locations

The RAF operated the Phantom from a number of bases in the UK, Germany and the Falkland Islands during its operational service, while the Royal Navy initially based its Phantom units at its main air station at Yeovilton; following the disbanding of the Fleet Air Arm's dedicated training squadron, its sole operational Phantom squadron was subsequently moved to take up residence at the RAF's base at Leuchars.

(map of North Rhine-Westphalia)

|

|

|

Basic specifications

| Variant | Powerplant | Speed (at 40,000 ft) | Ceiling | Range | Weight | Wingspan | Length | Height | Production total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empty | Maximum | |||||||||

| FG.1 [8] |

2 x RR Spey 203 low-bypass turbofan | 1,386 mph (2,231 km/h) | 57,200 ft (17,400 m) | 1,750 mi (2,820 km) | 31,000 lb (14,000 kg) | 58,000 lb (26,000 kg) | 38 ft 5 in (11.71 m) | 57 ft 7 in (17.55 m) | 16 ft 1 in (4.90 m)[lower-roman 5] | 52 |

| FGR.2 [8] |

2 x RR Spey 202/204 low-bypass turbofan | 118 | ||||||||

| F.3 [8] |

2 x GE J79-10B axial flow turbojet | 1,434 mph (2,308 km/h) | 61,900 ft (18,900 m) | 29,900 lb (13,600 kg) | 58 ft 3 in (17.75 m) | 16 ft 6 in (5.03 m) | 15 | |||

| Total number of UK F-4 Phantoms | 185 | |||||||||

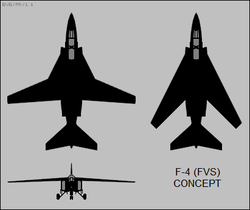

Other UK Phantom proposals

Although the Phantom was ordered in 1966, the variants that were eventually constructed were not the first to be offered to the UK. McDonnell Aircraft had been conducting studies into the possibility of the Royal Navy using the Phantom on its carriers since 1959. The company concluded that more power was needed than the J79 turbojet could provide to operate from the smaller decks of British carriers. The company spoke to Rolls-Royce about whether the RB-168 Spey turbofan, then in development for use in the Blackburn Buccaneer, could be fitted to the aircraft.[94] In 1960, McDonnell approached the RAF with its model number 98CJ, which was an F4H-1 (later F-4B) with various modifications, including the installation of the Rolls-Royce Spey Mk.101 turbofan.[95] McDonnell continued studies, proposing afterburning Spey 101 engines in 1962, while trials of an F-4B fitted with an extendable nosewheel oleo took place aboard USS Forrestal in 1963.[94] In 1964 the company proposed the model 98FC, which was identical to the F-4D variant but would have been fitted with the RB.168-25R version of the Spey engine.[96]

RF-4M

A further proposal came after the order for the F-4M was being finalized, and was a result of the UK's need for an aircraft to perform the tactical reconnaissance role. For this, McDonnell offered two options:[97]

- The standard F-4M fitted with a reconnaissance pod in place of the centerline fuel tank

- A modified airframe, designated as RF-4M, with the reconnaissance equipment carried internally

Although the RF-4M would have had some advantages, it was discounted as the cost would have been greater, with consequently fewer aircraft purchased, while only those that had been modified would have been able to undertake the reconnaissance mission. Ultimately, the RAF chose the standard F-4M and external pod, which allowed all of its aircraft to perform all designated roles.[98]

F-4(HL)

Another idea that McDonnell proposed was a variation of a carrier-based Phantom, with the goal of improving catapult performance and lowering approach speeds. The F-4(HL) would have had a longer fuselage and wingspan, with less sweep, stabilators with increased area and air intakes with auxiliary blow-in doors to increase airflow at low speeds. This proposal was not taken forward.[99]

Replacement

In the early 1970s, the RAF issued an Air Staff Requirement for the development of a new interceptor intended to replace both the Phantom and the Lightning.[63] An early proposal was McDonnell Douglas's plan for a Phantom with a variable-geometry wing. This was rejected by the RAF owing to the fact that there was little apparent improvement in performance over the existing Phantom, and that it might affect the development of the "Multi-Role Combat Aircraft" (MRCA).[100][101] Another idea that the MRCA concept, which eventually evolved into the Panavia Tornado, could be used in the interceptor role, was ruled out, as both its avionics and engines were optimised for low-level interdiction.[63] The UK's partners in the MRCA project displayed no enthusiasm for the idea of developing an air defence version of the Tornado, so the UK alone began the process, and the authorisation for what came to be known as the Tornado ADV was issued in March 1976.[63] The initial plan was for the Tornado to replace the remaining two squadrons of Lightnings, as well as all seven squadrons of Phantoms.[102] While the Tornado was in development, the RAF looked at interim measures to replace the Phantom, which had been in service for over a decade by 1980, and was beginning to suffer from fatigue;[103] one proposal considered was the possibility of leasing or purchasing F-15 Eagles to re-equip 19 and 92 Squadrons, the units stationed in Germany.[54] Further suggestions were that up to 80 F-15s be procured, to replace the Phantom and Lightning squadrons then in service, or even cancel the Tornado entirely and purchase the F-15 with UK adaptations (specifically to be fitted with the AI.24 Foxhunter radar developed for the Tornado, and capable of carrying the Skyflash air-to-air missile).[104] Ultimately, the F-15 option was not seriously considered, as it was felt there would not be time or cost savings over the Tornado ADV.[104] It was later decided that the Tornado, once it had entered service, would only re-equip three of the Phantom squadrons; two Phantom units would be retained in the UK, and two in Germany.[105] Eventually, the Tornado accounted for the two FG.1 squadrons at RAF Leuchars (43 and 111 Squadrons), plus two FGR.2 units (23 Squadron and 29 Squadron), while 56 and 74 Squadrons continued with the Phantom.[60]

In 1963, the prototype Hawker Siddeley P.1127 STOVL aircraft undertook initial landings aboard Ark Royal, while three years later pre-production Hawker Siddeley Kestrel (which subsequently became the Harrier), conducted a series of extensive trials from HMS Bulwark, which proved the concept of using vertical landing aircraft aboard aircraft carriers.[106] In the Royal Navy at the same time, the withdrawal of the conventional aircraft carrier was envisaged to see the end of fixed-wing aviation at sea. Because of this policy, 892 Naval Air Squadron used a black capital Omega (Ω) letter on the tailfins of their aircraft, as it was believed they would be the final fixed-wing squadron to be commissioned.[41] However, in the 1970s the Royal Navy was developing what was known as the "Through Deck Cruiser", a 20,000 ton ship with a full-length flight deck intended to embark a squadron of large anti-submarine warfare helicopters. Almost as soon as the first ship, HMS Invincible, was ordered, another specification was added to the design: as well as the helicopters, a small squadron of STOVL aircraft would form part of the air group to act as a deterrent to long-range reconnaissance aircraft.[107] To this end, a navalised version of the Harrier was developed – over the life of the design process, the Sea Harrier's air defence role was augmented by responsibility for reconnaissance and maritime strike missions. In March 1980, 14 months after 892 Naval Air Squadron was decommissioned and its Phantoms turned over to the RAF, 800 Naval Air Squadron was formed as the first operational Sea Harrier squadron.[108]

Aircraft replaced by and replacing the Phantom

Sir Sydney Camm, the Chief Designer at Hawker for many years, once said that no British aircraft could be considered a success until it was able to match the capabilities of the Phantom.[17] The Phantom's versatility was such that, in the RAF and Royal Navy, it was the direct replacement in squadron service for a total of four different aircraft types, comprising nine separate variants. In turn, when the Phantom was replaced, its major roles required three separate aircraft (see table):

| Unit | Formed | Variant | Role | Previous operations (withdrawn) | Disbanded | Replaced by | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700P NAS | 1968 | FG.1 | Operational Evaluation[lower-roman 6] | Wessex HAS.3[lower-roman 7] (1967) | 1969 | Sea King HAS.1[lower-roman 8] | [32][109] |

| 767 NAS | 1969 | Operational Conversion | N/A | 1972 | N/A[lower-roman 9] | ||

| 892 NAS | 1969 | Fleet Air Defence | Sea Vixen FAW.2 (1969) | 1978 | no replacement [lower-roman 10] | [110] | |

| 2 Sqn | 1970 | FGR.2 | Tactical Reconnaissance | Hunter FR.10 (1970) | 1976 | Jaguar GR.1 | [111][112] |

| 6 Sqn | 1969 | FGR.2 | Close Air Support/Tactical Strike | Canberra B.16 (1969) | 1974 | [113] | |

| 14 Sqn | 1970 | FGR.2 | Canberra B(I).8 (1970) | 1975 | [114] | ||

| 17 Sqn | 1970 | FGR.2 | Canberra PR.7[lower-roman 11] (1970) | 1975 | [115] | ||

| 19 Sqn | 1977 | FGR.2 | Air Defence | Lightning F.2A (1977) | 1992 | Hawk T.1[lower-roman 12] | [116] |

| 23 Sqn | 1975 | FGR.2 | Lightning F.3/F.6 (1975) | 1988 | Tornado F.3 | [117] | |

| 29 Sqn | 1975 | FGR.2 | Lightning F.3/F.6 (1975) | 1987 | [118] | ||

| 31 Sqn | 1971 | FGR.2 | Close Air Support/Tactical Strike | Canberra PR.7[xi] (1971) | 1976 | Jaguar GR.1 | [119] |

| 41 Sqn | 1972 | FGR.2 | Tactical Reconnaissance[lower-roman 13] | Bloodhound Mk.2 SAM (1970) | 1977 | [120] | |

| 43 Sqn | 1969 | FG.1 | Air Defence | Hunter FGA.9[lower-roman 14] (1967) | 1989 | Tornado F.3 | [121] |

| 54 Sqn | 1969 | FGR.2 | Close Air Support/Tactical Strike | Hunter FGA.9 (1969) | 1974 | Jaguar GR.1 | [122] |

| 56 Sqn | 1976 | FGR.2 | Air Defence | Lightning F.6 (1976) | 1992 | Tornado F.3[lower-roman 15] | [123] |

| 64 Sqn[lower-roman 16] | 1968 | FG.1/FGR.2 | Operational Conversion | Javelin FAW.7/FAW.9[lower-roman 17] (1967) | 1991 | N/A | [124] |

| 74 Sqn | 1984 | F.3[lower-roman 18] | Air Defence | Lightning F.6 (1971) | 1991 | Hawk T.1A[xii] | [125] |

| 92 Sqn | 1977 | FGR.2 | Lightning F.2A (1977) | 1992 | [126] | ||

| 111 Sqn | 1974 | FGR.2[lower-roman 19] | Lightning F.3/F.6 (1974) | 1990 | Tornado F.3 | [127] | |

| 1435 Flt | 1988 | FGR.2 | N/A[lower-roman 20] | 1992 | [128] |

Aircraft on display

List of Phantom aircraft on display that have been in service with the Royal Air Force or Royal Navy. The remaining aircraft were either lost in crashes or scrapped following withdrawal.[47]

YF-4K (prototype)

- XT596 Fleet Air Arm Museum, RNAS Yeovilton, Somerset, England.[129]

F-4K

- XT597 Bentwaters Airfield, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England – not on public display.[130]

- XT864 Maze-Long Kesh, Lisburn, Ulster Aviation Society, Northern Ireland.[131]

- XV582 RAF Leuchars, Fife, Scotland.[132]

- XV586 RNAS Yeovilton, Somerset, England – stored not on display.[133]

F-4M

- XT891 RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire, England.[134]

- XT889 Kbely Museum, Czech Republic.

- XT905 Bentwaters Airfield, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England – not on public display.[130]

- XT907 Bentwaters Airfield, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England

- XT914 Wattisham Airfield, Suffolk, England.[135]

- XV401 Bentwaters Airfield, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England.[136]

- XV406 Soloway Aviation Museum, Carlisle Airport, Cumbria, England.[137]

- XV408 Tangmere Military Aviation Museum, West Sussex, England.[138]

- XV411 Defence Fire Training and Development Centre, Manston Airport, Kent, England – not on public display.[139]

- XV415 RAF Boulmer, Alnwick, Northumberland, England.[140]

- XV424 Royal Air Force Museum London, England.[141]

- XV470 RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus – stored and not on public display.[142]

- XV474 Duxford Aerodrome, Cambridgeshire, England.[143]

- XV497 Bentwaters Airfield, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England.[136]

F-4J(UK)

- ZE359 American Air Museum, Duxford Aerodrome, Cambridgeshire, England. Painted in United States Navy markings.[144]

- ZE360 Defence Fire Training and Development Centre, Manston Airport, Kent, England – not on public display.[139]

Specifications (F-4M)

Data from Thunder & Lightnings – Phantom History[8]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 57 ft 7 in (17.55 m)

- Wingspan: 38 ft 4.5 in (11.7 m)

- Height: 16 ft 1 in (4.9 m)

- Empty weight: 31,000 lb (14,061 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 56,000 lb (25,402 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Spey 202/204 low bypass turbofans, 12,140 lbf dry thrust (54 kN), 20,500 lbf in afterburner (91.2 kN) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.9 (1,386 mph) at 40,000 ft (12,190 m)

- Ferry range: 1,750 mi (2,816 km)

- Service ceiling: 60,000 ft (18,300 m)

Armament

- Air defence

- 4 × AIM-7 Sparrow or Skyflash in fuselage recesses plus 4 × AIM-9 Sidewinders on wing pylons;

- 1 × 20 mm (0.787 in) M61 Vulcan 6-barrel Gatling cannon in SUU-23 gun pod

- Strike

Avionics

- Ferranti AN/AWG-12 Multi-Mode Radar

- Marconi ARI18228 Radar Warning Receiver

- Marconi AN/ASN-39A computer

- AN/ARN-91 TACAN bearing/distance navigation system

- Cossor IFF

- STR-70P Radio Altimeter

- EMI Reconnaissance Pod containing:

- 2 × F.135 forward facing camera

- 4 × F.95 oblique facing camera

- Texas Instruments RS700 Infra-Red Linescan

- MEL/EMI Q-Band Sideways Looking Reconnaissance Radar

References

- Notes

- ↑ Victorious departed on her final commission with a total of 10 Sea Vixens and 7 Buccaneers;[24] by contrast, Ark Royal was able to accommodate an air group including up to 12 Phantoms and 14 Buccaneers,[25]

- ↑ Although Eagle and Ark Royal were the largest ships in the UK's carrier fleet, some sources have stated that the plan for Phantom operation was to see aircraft obtained for use aboard Ark Royal and Victorious[26][27]

- ↑ The launch bridle for the Phantom could only be used on that type, and was thus considerably more expensive than those used for other types. As a consequence, bridle catchers were fitted to the ends of the ship's new catapults so that the bridles could be reused.[37]

- ↑ While undertaking trials aboard US carriers, the higher exhaust temperatures caused by the Spey turbofan led to significant damage to the flight decks of the American ships[37]

- ↑ 16 ft 9 in (5.11 m) with Radar Warning Receiver

- ↑ 700 NAS is the assigned number to all units evaluating new aircraft for the Fleet Air Arm

- ↑ As 700H NAS

- ↑ As 700S NAS

- ↑ Phantom conversion training was undertaken by the FAA Phantom Training Flight following the disbanding of 767 NAS

- ↑ Following the decommissioning of HMS Ark Royal in 1978, the Royal Navy was no longer able to operate conventional fixed wing aircraft at sea. The British Aerospace Sea Harrier was introduced into both the air defence (replacing the Phantom) and strike (replacing the Buccaneer) roles in the Fleet Air Arm with 800 NAS and 801 NAS in 1980

- ↑ The Canberra was used in the tactical reconnaissance role

- ↑ The instances where the Phantom was replaced in squadron service by the Hawk were a result of the "Options for Change" defence cuts, with the squadrons being transferred to training roles

- ↑ 41 Squadron converted to this role from being an air defence SAM squadron

- ↑ The Hunter was used in the close air support role

- ↑ This unit became the "shadow" squadron number of 229 OCU, the Tornado OCU

- ↑ This was the "shadow" squadron number of 228 OCU

- ↑ The Javelin squadron was an operational interceptor unit

- ↑ 74 Squadron converted to the FGR.2 in 1991 prior to disbanding

- ↑ 111 Squadron converted to the FG.1 in 1979

- ↑ The original 1435 Flight served from December 1941 to April 1945

- Citations

- 1 2 Lake 1992.

- ↑ "An Industry Regrouped" (pdf). Flight. Iliffe & Sons. 78 (2686): 367–373. 2 September 1960. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Lessons of the TSR.2 Story" (pdf). Flight International. Iliffe & Sons. 96 (3161): 570–571. 9 October 1969. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Buttler 2000, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Burke 2010, p. 274.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of the P.1154" (PDF). Hawker Association Newsletter. Hawker Association: 4–5. Summer 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Burke, Damien (12 April 2012). "Phantom History". Thunder & Lightnings. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Thornborough and Davies 1994, p. 260.

- ↑ "HMS Hermes 1962–1964" (PDF). Axford's Abode. 1964. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ↑ Hobbs 2014, p. 280

- ↑ Goebel, Greg (1 February 2014). "Phantom In Foreign Service". The McDonnell DOuglas F-4 Phantom. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ Flintham, Vic (2011). "McDonnell Phantom". vicflintham.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ Richardson 1984, p. 26

- 1 2 3 4 Courtnage, Paul (2006). "Chapter 5: The Phantom". Vox Clamantis in Deserto. Project Ocean Vision. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ "McDonnell-Douglas F-4 Phantom". Warbird Alley. Doublestar Group. 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hobbs, David (2008). "British F-4 Phantoms". Air International. Key Publishing. 74 (5): 30–37.

- ↑ Sturtivant 2004, pp. 470–471

- ↑ Petit et al 1983, p. 172

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Serials in range XT". UK Serials Resource Centre. Wolverhampton Aviation Group. 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Serials in range XV". UK Serials Resource Centre. Wolverhampton Aviation Group. 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- 1 2 "History". Phantom F4K Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Hobbs, David (2014). British Aircraft Carriers: Design, Development & Service Histories. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781848321380.

- ↑ "British Carriers at Portsmouth 1954-2011". Hampshire Airfields. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Benbow, 2011, p. 182

- 1 2 Davies, p. 31

- ↑ Beedle, p. 197

- ↑ Toppan, Andrew (24 April 2000). "RN Postwar Attack Carriers". World Aircraft Carriers List. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Hobbs, 1982, p. 20

- ↑ Hobbs, 1982, p. 38

- 1 2 "McDonnell F-4K Phantom FG.Mk.1". Phabulous Phantom. 30 December 1999. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Royal Navy Squadrons". Phantom F4K Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ "Not a Lot of People Know That...". National Cold War Exhibition. RAF Museum. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Phantoms On HMS Eagle (Film). British Pathé. 8 June 1969. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- 1 2 "HMS Eagle Deck Trials 1969". www.phantomf4k.org. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ "Spray-type Arresting Gear". Flight International. Hiffe Transport Publications. 82 (2787): 183. 9 August 1962. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Caygill 2005, p. 42-43

- 1 2 "McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II". www.aviation-history.com. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ "892 Squadron record of service". Phantom F4K Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "F-4 Phantom – UK". ejection-history.org.uk. 15 November 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- 1 2 Kent, Rick (22 September 2006). "McDonnell Phantom in British Service". IPMS Stockholm. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ "Royal Air Force Phantom Squadrons". RAF Yearbook. IAT Publishing: 17. 1992.

- ↑ "No. 11 Squadron". The Lightning Association. June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Burke, Damien (4 April 2012). "Lightning History". Thunder & Lightnings. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "RAF Leuchars saying farewell to Treble One's Tornado F3s". The Courier. 18 March 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ "Clydeside Carnage: The Battered Remains of RAF Leuchars' Phantom Fleet". Urban Ghosts. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Phantom FG-1, FGR-2 & F-4J (UK) Aircraft Histories.". The Phantom Shrine. Corsair Publishing. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Burke, Damian (12 April 2012). "Survivors". Thunder & Lightnings. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ "McDonnell F-4M Phantom FGR.Mk.2". Phabulous Phantom. 30 December 1999. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Tactical Nuclear Weapons. 1971–1972.". The National Archives. p. 5. DEFE 11/470 E30. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- 1 2 Norris, p. 64

- ↑ "McDonnell Douglas Phantom FGR-2 EMI Reconnaissance Pod". Post WW2. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ Braybrook, Ray (1981). "Lightning". RAF Yearbook. Leicester: WM Caple: 53.

- 1 2 Fricker, John (1980). "The RAF Looks Ahead". RAF Yearbook. Leicester: Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund.

- ↑ Courtnage, Paul (2016). "Tornado". Vox Clamantis in Deserto. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "Tornado F.3: Tremblers' Farewell – the end of the Tornado F.3". Global Aviation Resource. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ Eade, Dave. "Phantastic Phantom's arrival". The Wattisham Chronicles. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Gordon (31 May 2013). "Part 15. Royal Air Force – Role & Operations". Battle Atlas of the Falkalnds War 1982 by Land, Sea and Air. naval-history.net. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ "29(R) Squadron". Royal Air Force. 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Archer, Bob (1992). "Sunset for the Phantom". RAF Yearbook. IAT Publishing: 14.

- ↑ Peacock, Lindsay (1990). "For F4 Read F3". RAF Yearbook. Fairford: IAT Publishing.

- ↑ Jackson, Paul (1988). "Farewell Lightning, Welcome Tornado". RAF Yearbook. Fairford: IAT Publishing.

- 1 2 3 4 Darling 2012, p.189

- ↑ Tom King, Secretary of State for Defence (25 July 1990). "Defence (Options for Change)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 468–486.

- ↑ "RAF Akrotiri – History". RAF Akrotiri Revisited. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Serials in range ZE". UK Serials Resource Centre. Wolverhampton Aviation Group. 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ Damien Burke. "McDonnell-Douglas/BAC F-4K/M Phantom II - History". www.thunder-and-lightnings.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ "The Modern Era: Hawks & Phantoms". No 74 Squadron Association. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- 1 2 Davies, p. 30

- 1 2 3 Rawlings, John (1985). "The Tigers Are Back". RAF Yearbook. ABC: 33.

- ↑ "RAF Timeline 1980–1989". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

No 74 Squadron reforms at Wattisham with the delivery of the first of the F4J Phantoms, given the RAF designation Phantom F3

- ↑ "No 74 Squadron". National Cold War Exhibition. Royal Air Force Museum. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ Bourne, Nigel. "Development of the Rolls-Royce Military Spey Mk202 Engine". Thrust SSC. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- 1 2 "Weaponry". National Cold War Exhibition. RAF Museum. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Davies, p. 24

- 1 2 3 The Phantom and the Spey (Information plaque in museum). RAF Museum, Hendon: Royal Air Force Museum. 2003.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg (1 February 2014). "Phantom In Foreign Service". The McDonnell F-4 Phantom. airvectors.net. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ Eade, Dave. "Part Five:Phantastic Phantom's Arrival". The Wattisham Chronicles. Air Scene UK. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Burns, J.G.; Edwards, M. (14 January 1971). "Blow, Blow Thou BLC Wind". Flight International. Flight Global. 99 (3227): 56–59. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Catapults & Ski Ramps". Modern Naval Vessel Design Evaluation Tool. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ↑ "Equipment Fit". National Cold War Exhibition. RAF Museum. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Burke, Damien (11 January 2012). "XT596 – Fleet Air Arm Museum, RNAS Yeovilton, Somerset". Thunder and Lightnings. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Parson, Gary (23 June 2002). "Midsummer Phantom". airsceneuk.org.uk. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "Today in Aviation History". Flight. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

◾Royal Navy Hawker-Siddeley/McDonnell-Douglas F-4K Phantom II FG.1, XT598, used for trials installations at HSA Holme and A&AEE, Boscombe Down, then passed to 111 Squadron. Written off on approach to Leuchars this date. - Thursday 23rd Nov, 1978

- 1 2 3 "A & AEE. (Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment)". Phantom F4K Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Daily Mail Trans-Atlantic Record Holder 1969". Phantom F4K - Fleet Air Arm Royal Navy. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ "On this day 27 November 1978". Fleet Air Arm Officers Association. 27 November 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Armament Practice Camps – McD F-4 Phantom FG.1/FGR.2". Aviation in Malta. 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 55364". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Burke, Damien (11 January 2012). "XV474 – Imperial War Museum, Duxford, Cambridgeshire". Thunder and Lightnings. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Museum Aircraft". Bentwaters Cold War Museum. 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2016.