One-way compression function

In cryptography, a one-way compression function is a function that transforms two fixed-length inputs into a fixed-length output.[1] The transformation is "one-way", meaning that it is difficult given a particular output to compute inputs which compress to that output. One-way compression functions are not related to conventional data compression algorithms, which instead can be inverted exactly (lossless compression) or approximately (lossy compression) to the original data.

One-way compression functions are for instance used in the Merkle–Damgård construction inside cryptographic hash functions.

One-way compression functions are often built from block ciphers. Some methods to turn any normal block cipher into a one-way compression function are Davies–Meyer, Matyas–Meyer–Oseas, Miyaguchi–Preneel (single-block-length compression functions) and MDC-2/Meyer–Schilling, MDC-4, Hirose (double-block-length compression functions). These methods are described in detail further down. (MDC-2 is also the name of a hash function patented by IBM.)

Compression

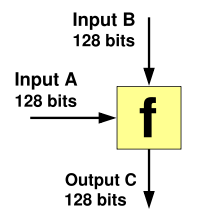

A compression function mixes two fixed length inputs and produces a single fixed length output of the same size as one of the inputs. This can also be seen as that the compression function transforms one large fixed-length input into a shorter, fixed-length output.

For instance, input A might be 128 bits, input B 128 bits and they are compressed together to a single output of 128 bits. This is equivalent to having a single 256-bit input compressed to a single output of 128 bits.

Some compression functions do not compress by half, but instead by some other factor. For example, input A might be 256 bits, and input B 128 bits, which are compressed to a single output of 128 bits. That is, a total of 384 input bits are compressed together to 128 output bits.

The mixing is done in such a way that full avalanche effect is achieved. That is, every output bit depends on every input bit.

One-way

A one-way function is a function that is easy to compute but hard to invert. A one-way compression function (also called hash function) should have the following properties:

- Easy to compute: If you have some input(s), it is easy to calculate the output.

- Preimage-resistance: If an attacker only knows the output it should be unfeasible to calculate an input. In other words, given an output h, it should be unfeasible to calculate an input m such that hash(m)=h.

- Second preimage-resistance: Given an input m1 whose output is h, it should be unfeasible to find another input m2 that has the same output h i.e. hash(m1)=hash(m2).

- Collision-resistance: It should be hard to find any two different inputs that compress to the same output i.e. an attacker should not be able to find a pair of messages m1 ≠ m2 such that hash(m1) = hash(m2). Due to the birthday paradox (see also birthday attack) there is a 50% chance a collision can be found in time of about 2n/2 where n is the number of bits in the hash function's output. An attack on the hash function thus should not be able to find a collision with less than about 2n/2 work.

Ideally one would like the "unfeasibility" in preimage-resistance and second preimage-resistance to mean a work of about 2n where n is the number of bits in the hash function's output. However, particularly for second preimage-resistance this is a difficult problem.

The Merkle–Damgård construction

A common use of one-way compression functions is in the Merkle–Damgård construction inside cryptographic hash functions. Most widely used hash functions, including MD5, SHA-1 and SHA-2 use this construction.

A hash function must be able to process an arbitrary-length message into a fixed-length output. This can be achieved by breaking the input up into a series of equal-sized blocks, and operating on them in sequence using a one-way compression function. The compression function can either be specially designed for hashing or be built from a block cipher.

The last block processed should also be length padded, this is crucial to the security of this construction. This construction is called the Merkle–Damgård construction. Most widely used hash functions, including SHA-1 and MD5, take this form.

When length padding (also called MD-strengthening) is applied, attacks cannot find collisions faster than the birthday paradox (2n/2, n is the block size in bits) if the used f-function is collision-resistant.[2][3] Hence, the Merkle–Damgård hash construction reduces the problem of finding a proper hash function to finding a proper compression function.

A second preimage attack (given a message m1 an attacker finds another message m2 to satisfy hash(m1) = hash(m2) ) can be done according to Kelsey and Schneier [4] for a 2k-message-block message in time k x 2n/2+1+2n-k+1. Note that the complexity is above 2n/2 but below 2n when messages are long and that when messages get shorter the complexity of the attack approaches 2n.

Construction from block ciphers

One-way compression functions are often built from block ciphers.

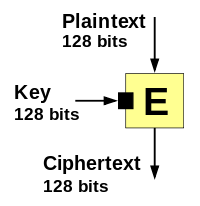

Block ciphers take (like one-way compression functions) two fixed size inputs (the key and the plaintext) and return one single output (the ciphertext) which is the same size as the input plaintext.

However, modern block ciphers are only partially one-way. That is, given a plaintext and a ciphertext it is infeasible to find a key that encrypts the plaintext to the ciphertext. But, given a ciphertext and a key a matching plaintext can be found simply by using the block cipher's decryption function. Thus, to turn a block cipher into a one-way compression function some extra operations have to be added.

Some methods to turn any normal block cipher into a one-way compression function are Davies–Meyer, Matyas–Meyer–Oseas, Miyaguchi–Preneel (single-block-length compression functions) and MDC-2, MDC-4, Hirose (double-block-length compressions functions).

Single-block-length compression functions output the same number of bits as processed by the underlying block cipher. Consequently, double-block-length compression functions output twice the number of bits.

If a block cipher has a block size of say 128 bits single-block-length methods create a hash function that has the block size of 128 bits and produces a hash of 128 bits. Double-block-length methods make hashes with double the hash size compared to the block size of the block cipher used. So a 128-bit block cipher can be turned into a 256-bit hash function.

These methods are then used inside the Merkle-Damgård construction to build the actual hash function. These methods are described in detail further down.

Using a block cipher to build the one-way compression function for a hash function is usually somewhat slower than using a specially designed one-way compression function in the hash function. This is because all known secure constructions do the key scheduling for each block of the message. Black, Cochran and Shrimpton have shown that it is impossible to construct a one-way compression function that makes only one call to a block cipher with a fixed key.[5] In practice reasonable speeds are achieved provided the key scheduling of the selected block cipher is not a too heavy operation.

But, in some cases it is easier because a single implementation of a block cipher can be used for both block cipher and a hash function. It can also save code space in very tiny embedded systems like for instance smart cards or nodes in cars or other machines.

Therefore, the hash-rate or rate gives a glimpse of the efficiency of a hash function based on a certain compression function. The rate of an iterated hash function outlines the ratio between the number of block cipher operations and the output. More precisely, if n denotes the output bit-length of the block cipher the rate represents the ratio between the number of processed bits of input m, n output bits and the necessary block cipher operations s to produce these n output bits. Generally, the usage of less block cipher operations could result in a better overall performance of the entire hash function but it also leads to a smaller hash-value which could be undesirable. The rate is expressed in the formula .

The hash function can only be considered secure if at least the following conditions are met:

- The block cipher has no special properties that distinguish it from ideal ciphers, such as for example weak keys or keys that lead to identical or related encryptions (fixed points or key-collisions).

- The resulting hash size is big enough. According to the birthday attack a security level of 280 (generally assumed to be infeasible to compute today) is desirable thus the hash size should be at least 160 bits.

- The last block is properly length padded prior to the hashing. (See Merkle–Damgård construction.) Length padding is normally implemented and handled internally in specialised hash functions like SHA-1 etc.

The constructions presented below: Davies–Meyer, Matyas–Meyer–Oseas, Miyaguchi–Preneel and Hirose have been shown to be secure under the black-box analysis.[6][7] The goal is to show that any attack that can be found is at most as efficient as the birthday attack under certain assumptions. The black-box model assumes that a block cipher is used that is randomly chosen from a set containing all appropriate block ciphers. In this model an attacker may freely encrypt and decrypt any blocks, but does not have access to an implementation of the block cipher. The encryption and decryption function are represented by oracles that receive a pair of either a plaintext and a key or a ciphertext and a key. The oracles then respond with a randomly chosen plaintext or ciphertext, if the pair was asked for the first time. They both share a table for these triplets, a pair from the query and corresponding response, and return the record, if a query was received for the second time. For the proof there is a collision finding algorithm that makes randomly chosen queries to the oracles. The algorithm returns 1, if two responses result in a collision involving the hash function that is built from a compression function applying this block cipher (0 else). The probability that the algorithm returns 1 is dependent on the number of queries which determine the security level.

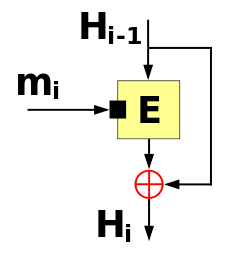

Davies–Meyer

The Davies–Meyer single-block-length compression function feeds each block of the message (mi) as the key to a block cipher. It feeds the previous hash value (Hi-1) as the plaintext to be encrypted. The output ciphertext is then also XORed () with the previous hash value (Hi-1) to produce the next hash value (Hi). In the first round when there is no previous hash value it uses a constant pre-specified initial value (H0).

In mathematical notation Davies–Meyer can be described as:

The scheme has the rate (k is the keysize):

If the block cipher uses for instance 256-bit keys then each message block (mi) is a 256-bit chunk of the message. If the same block cipher uses a block size of 128 bits then the input and output hash values in each round is 128 bits.

Variations of this method replace XOR with any other group operation, such as addition on 32-bit unsigned integers.

A notable property of the Davies–Meyer construction is that even if the underlying block cipher is totally secure, it is possible to compute fixed points for the construction : for any , one can find a value of such that : one just has to set .[8] This is a property that random functions certainly do not have. So far, no practical attack has been based on this property, but one should be aware of this "feature". The fixed-points can be used in a second preimage attack (given a message m1, attacker finds another message m2 to satisfy hash(m1) = hash(m2) ) of Kelsey and Schneier [4] for a 2k-message-block message in time 3 x 2n/2+1+2n-k+1 . If the construction does not allow easy creation of fixed points (like Matyas–Meyer–Oseas or Miyaguchi–Preneel) then this attack can be done in k x 2n/2+1+2n-k+1 time. Note that in both cases the complexity is above 2n/2 but below 2n when messages are long and that when messages get shorter the complexity of the attack approaches 2n.

The security of the Davies–Meyer construction in the Ideal Cipher Model was first proved by R. Winternitz.[9]

Matyas–Meyer–Oseas

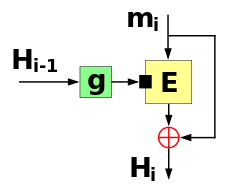

The Matyas–Meyer–Oseas single-block-length one-way compression function can be considered the dual (the opposite) of Davies–Meyer.

It feeds each block of the message (mi) as the plaintext to be encrypted. The output ciphertext is then also XORed () with the same message block (mi) to produce the next hash value (Hi). The previous hash value (Hi-1) is fed as the key to the block cipher. In the first round when there is no previous hash value it uses a constant pre-specified initial value (H0).

If the block cipher has different block and key sizes the hash value (Hi-1) will have the wrong size for use as the key. The cipher might also have other special requirements on the key. Then the hash value is first fed through the function g( ) to be converted/padded to fit as key for the cipher.

In mathematical notation Matyas–Meyer–Oseas can be described as:

The scheme has the rate:

A second preimage attack (given a message m1 an attacker finds another message m2 to satisfy hash(m1) = hash(m2) ) can be done according to Kelsey and Schneier[4] for a 2k-message-block message in time k x 2n/2+1+2n-k+1. Note that the complexity is above 2n/2 but below 2n when messages are long and that when messages get shorter the complexity of the attack approaches 2n.

Miyaguchi–Preneel

The Miyaguchi–Preneel single-block-length one-way compression function is an extended variant of Matyas–Meyer–Oseas. It was independently proposed by Shoji Miyaguchi and Bart Preneel.

It feeds each block of the message (mi) as the plaintext to be encrypted. The output ciphertext is then XORed () with the same message block (mi) and then also XORed with the previous hash value (Hi-1) to produce the next hash value (Hi). The previous hash value (Hi-1) is fed as the key to the block cipher. In the first round when there is no previous hash value it uses a constant pre-specified initial value (H0).

If the block cipher has different block and key sizes the hash value (Hi-1) will have the wrong size for use as the key. The cipher might also have other special requirements on the key. Then the hash value is first fed through the function g( ) to be converted/padded to fit as key for the cipher.

In mathematical notation Miyaguchi–Preneel can be described as:

The scheme has the rate:

The roles of mi and Hi-1 may be switched, so that Hi-1 is encrypted under the key mi. Thus making this method an extension of Davies–Meyer instead.

A second preimage attack (given a message m1 an attacker finds another message m2 to satisfy hash(m1) = hash(m2) ) can be done according to Kelsey and Schneier[4] for a 2k-message-block message in time k x 2n/2+1+2n-k+1. Note that the complexity is above 2n/2 but below 2n when messages are long and that when messages get shorter the complexity of the attack approaches 2n.

Hirose

The Hirose[7] double-block-length one-way compression function consists of a block cipher plus a permutation p. It was proposed by Shoichi Hirose in 2006 and is based on a work[10] by Mridul Nandi.

It uses a block cipher whose key length k is larger than the block length n, and produces a hash of size 2n. For example, any of the AES candidates with a 192- or 256-bit key (and 128-bit block).

Each round accepts a portion of the message mi that is k−n bits long, and uses it to update two n-bit state values G and H.

First, mi is concatenated with Hi−1 to produce a key Ki. Then the two feedback values are updated according to:

- Gi = EKi(Gi−1) ⊕ Gi−1

- Hi = EKi(p(Gi−1)) ⊕ p(Gi−1).

p(Gi−1) is an arbitrary fixed-point-free permutation on an n-bit value, typically defined as

- p(x) = x ⊕ c

for an arbitrary non-zero constant c. (All-ones may be a convenient choice.)

Each encryption resembles the standard Davies–Meyer construction. The advantage of this scheme over other proposed double-block-length schemes is that both encryptions use the same key, and thus key scheduling effort may be shared.

The final output is Ht||Gt. The scheme has the rate RHirose = (k−n)/2·n relative to encrypting the message with the cipher.

Hirose also provides a proof in the Ideal Cipher Model.

See also

- WHIRLPOOL – A cryptographic hash function built using the Miyaguchi–Preneel construction and a block cipher similar to Square and AES.

- CBC-MAC, OMAC and PMAC – Methods to turn block ciphers into message authentication codes (MACs).

References

- ↑ Handbook of Applied Cryptography by Alfred J. Menezes, Paul C. van Oorschot, Scott A. Vanstone. Fifth Printing (August 2001) page 328.

- ↑ Ivan Damgård. A design principle for hash functions. In Gilles Brassard, editor, CRYPTO, volume 435 of LNCS, pages 416–427. Springer, 1989.

- ↑ Ralph Merkle. One way hash functions and DES. In Gilles Brassard, editor, CRYPTO, volume 435 of LNCS, pages 428–446. Springer, 1989.

- 1 2 3 4 John Kelsey and Bruce Schneier. Second preimages on n-bit hash functions for much less than 2n work. In Ronald Cramer, editor, EUROCRYPT, volume 3494 of LNCS, pages 474–490. Springer, 2005.

- ↑ John Black, Martin Cochran, and Thomas Shrimpton. On the Impossibility of Highly-Efficient Blockcipher-Based Hash Functions. Advances in Cryptology -- EUROCRYPT '05, Aarhus, Denmark, 2005. The authors define a hash function "highly efficient if its compression function uses exactly one call to a block cipher whose key is fixed".

- ↑ John Black, Phillip Rogaway, and Tom Shrimpton. Black-Box Analysis of the Block-Cipher-Based Hash-Function Constructions from PGV. Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO '02, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 2442, pp. 320-335, Springer, 2002. See the table on page 3, Davies–Meyer, Matyas–Meyer–Oseas and Miyaguchi–Preneel are numbered in the first column as hash functions 5, 1 and 3.

- 1 2 S. Hirose, Some Plausible Constructions of Double-Block-Length Hash Functions. In: Robshaw, M.J.B. (ed.) FSE 2006, LNCS, vol. 4047, pp. 210-225, Springer, Heidelberg 2006.

- ↑ Handbook of Applied Cryptography by Alfred J. Menezes, Paul C. van Oorschot, Scott A. Vanstone. Fifth Printing (August 2001) page 375.

- ↑ R. Winternitz. A secure one-way hash function built from DES. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Information Security and Privacy, p. 88-90. IEEE Press, 1984.

- ↑ M. Nandi, Towards optimal double-length hash functions, In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Cryptology in India (INDOCRYPT 2005), Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3797, pages 77–89, 2005.

- Menezes; van Oorschot; Vanstone (2001). "Hash Functions and Data Integrity" (PDF). Handbook of Applied Cryptography.

- Bartkewitz, Timo (2009). "Building Hash Functions from Block Ciphers, Their Security and Implementation Properties".