Vosges

| Vosges | |

|---|---|

|

Location of the Vosges | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Grand Ballon (Alsatian: Großer Belchen) |

| Elevation | 1,424 m (4,672 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 120 km (75 mi) |

| Area | 5,500 km2 (2,100 sq mi) up to 6,000 km2 (2,300 sq mi) depending on the natural region boundaries selected |

| Geography | |

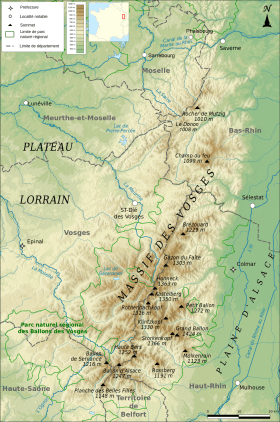

Map of the Vosges Mountains

| |

| Country | France |

| Region | Grand-Est, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté |

| Range coordinates | 48°N 7°E / 48°N 7°ECoordinates: 48°N 7°E / 48°N 7°E |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Low mountain range |

| Age of rock |

Gneiss, granite and vulcanite stratigraphic units: about 419–252 mya Bunter sandstone stratigraphic unit: 252–243 mya |

| Type of rock | Gneiss, granite, vulcanite, sandstone |

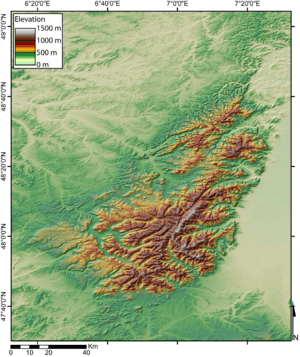

The Vosges (French pronunciation: [voʒ]; German: Vogesen [voˈɡeːzn̩]), also called the Vosges Mountains, are a range of low mountains in eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single geomorphological unit and low mountain range of around 8,000 km2 (3,100 sq mi) in area. It runs in a north-northeast direction from the Burgundian Gate (the Belfort–Ronchamp–Lure line) to the Börrstadt Basin (the Winnweiler–Börrstadt–Göllheim line), and forms the western boundary of the Upper Rhine Plain.

The Grand Ballon is the highest peak at 1,424 m (4,672 ft), followed by the Storkenkopf (1,366 m, 4,482 ft), and the Hohneck (1,364 m, 4,475 ft).[1]

Geography

The elongated massif is divided south to north into three sections:

- The Higher Vosges or High Vosges[2] (Hautes Vosges), extending in the southern part of the range from Belfort to the river valley of the Bruche. The rounded summits of the Hautes Vosges are called ballons in French, literally "balls".

- The sandstone Vosges or Middle Vosges[2] (50 km, 31 mi), between the Permian Basin of Saint-Die including the Devonian-Dinantian volcanic massif of Schirmeck-Moyenmoutier and the Col de Saverne

- The Lower Vosges or Low Vosges[2] (48 km, 30 mi), between the Col de Saverne and the source of the Lauter.

In addition, the term "Central Vosges" is used to designate the various lines of summits, especially those above 1,000 m (3,300 ft) in elevation. The French department of Vosges is named after the range.

From a geological point of view, a graben at the beginning of the Paleogene Period caused the formation of Alsace and the uplift of the plates of the Vosges, now considered in eastern France, and those in the Black Forest, now in Germany. From a scientific view, the Vosges Mountains are not mountains as such, but rather the western edge of the unfinished Alsatian graben, stretching continuously as part of the larger Tertiary formations. Erosive glacial action was the primary catalyst for development of the representative highland massif feature.

Geographically, the Vosges Mountains are wholly in France, far above the Col de Saverne separating them from the Palatinate Forest in Germany. The latter area logically continues the same Vosges geologic structure but traditionally receives this different name for historical and political reasons. From 1871 to 1918 the Vosges marked the border between Germany and France, due to the Franco-Prussian War.

The Vosges in their southern and central parts are called the Hautes Vosges. These consist of a large Carboniferous mountain eroded just before the Permian Period with gneiss, granites, porphyritic masses or other volcanic intrusions. In the north, south and west, there are places less eroded by glaciers, and here Vosges Triassic and Permian red sandstone remains are found in large beds. The grès vosgien, (a French name for a Triassic rose sandstone) are embedded sometimes up to more than 500 m (1,600 ft) in thickness. The Lower Vosges in the north are dislocated plates of various sandstones, ranging from 300 to 600 m (1,000 to 2,000 ft) high.

The highest points are in the Hautes Vosges: the Grand Ballon, in ancient times called Ballon de Guebwiller or Ballon de Murbach, rises to 1,424 m (4,672 ft); the Storckenkopf to 1,366 m (4,482 ft); the Hohneck to 1,364 m (4,475 ft); the Kastelberg to 1,350 m (4,429 ft); and the Ballon d'Alsace to 1,247 m (4,091 ft). The Col de Saales, between the Higher and Central Vosges, reaches nearly 579 m (1,900 ft), both lower and narrower than the Higher Vosges, with Mont Donon at 1,008 m (3,307 ft) being the highest point of this Nordic section.

The Vosges is greatly similar to the corresponding range of the Black Forest on the other side of the Rhine: both lie within the same degrees of latitude, have similar geological formations, and are characterized by forests on their lower slopes, above which are open pastures and rounded summits of a rather uniform altitude. Both areas exhibit steeper slopes towards the Rhine River and a more gradual descent on the other side. This occurs because both the Vosges and the Black Forest were formed by isostatic uplift, in a response to the opening of the Rhine Graben. The Rhine Graben is a major extensional basin. When such basins form, the thinning of the crust causes uplift immediately adjacent to the basin. The amount of uplift decreases with distance from the basin, causing the highest range of peaks to be immediately adjacent to the basin, and the increasingly lower mountains to stretch away from the basin.

Mountains

The highest mountains of the Vosges (with Alsatian or German names in brackets) are:

- Grand Ballon (Großer Belchen) 1,424 m (4,672 ft)

- Storkenkopf 1,366 m (4,482 ft)

- Hohneck 1,363 m (4,472 ft)

- Kastelberg 1,350 m (4,429 ft)

- Klintzkopf (Klinzkopf) 1,330 m (4,364 ft)

- Rothenbachkopf 1,316 m (4,318 ft)

- Lauchenkopf 1,314 m (4,311 ft)

- Batteriekopf 1,311 m (4,301 ft)

- Haut de Falimont 1,306 m (4,285 ft)

- Gazon du Faing 1,306 m (4,285 ft)

- Rainkopf 1,305 m (4,281 ft)

- Gazon du Faîte 1,303 m (4,275 ft)

- Ringbuhl (Ringbühl) 1,302 m (4,272 ft)

- Soultzereneck (Sulzereneck) 1,302 m (4,272 ft)

The following is a selection of other peaks in the Vosges:

- Le Tanet (Tanneck) 1,292 m (4,239 ft)

- Petit Ballon (Kahler Wasen or Kleiner Belchen) 1,272 m (4,173 ft)

- Ballon d'Alsace (Elsässer Belchen) 1,247 m (4,091 ft)

- Brézouard 1,229 m (4,032 ft)

- Ballon de Servance (highest point in the département of Haute-Saône) 1,216 m (3,990 ft)

- Drumont 1,200 m (3,937 ft)

- Planche des Belles Filles 1,148 m (3,766 ft)

- Molkenrain 1,123 m (3,684 ft)

- Champ du Feu (Hochfeld or Firstfeld) 1,099 m (3,606 ft)

- Baerenkopf 1,074 m (3,524 ft)

- Rocher de Mutzig (Mutzigfelsen) 1,010 m (3,314 ft)

- Donon 1,009 m (3,310 ft)

- Taennchel (Tännchel) 992 m (3,255 ft)

- Climont 965 m (3,166 ft)

- Hartmannswillerkopf (Hartmannsweilerkopf) 956 m (3,136 ft)

- Chatte Pendue 902 m (2,959 ft)

- Ungersberg 901 m (2,956 ft)

- Tête du Coquin 837 m (2,746 ft)

- Mont St. Odile (Odilienberg) 760 m (2,493 ft)

- Dabo (Dagsburg) 647 m (2,123 ft)

- Grand Wintersberg (Großer Wintersberg) 581 m (1,906 ft)

- Hohenbourg (Hohenburg) 550 m (1,804 ft)

Climate

Meteorologically, as a consequence of the Foehn effect the difference between the eastern and western mean slopes of the range is very marked. The main air streams come generally from the west and southwest, so the Alsatian central plains just under the Hautes-Vosges receive much less water than the south-west front of the Vosges Mountains. The highlands of the arrondissement of Remiremont receive as annual rainfall or snowfall more than 2 m (6 ft 7 in) of precipitation yearly, whereas some dry country near Colmar receives less than 500 mm (20 in) of water in the event of insufficient storms. The temperature is much lower in the west front of the mountains than in the low plains behind the massif, especially in summer. On the eastern slope economic vineyards reach to a height of 400 m (1,300 ft); on the other hand, in the mountains, it is a land of pasture and forest.

The only rivers in Alsace are the Ill coming from south Alsace (or Sundgau), and the Bruche d'Andlau and the Bruche which have as tributaries other, shorter but sometimes powerful streams coming like the last two from the Vosges Mountains. The Moselle, Meurthe and Sarre rivers and their numerous affluents all rise on the Lorraine side.

In the High Moselle and Meurthe basins, moraines, boulders and polished rocks testify to the former existence of glaciers which once covered the top of the Vosges. The mountain lakes caused by the original glacial phenomena are surrounded by pines, beeches and maples, and green meadows provide pasture for large herds of cattle, with views of the Rhine valley, the Black Forest and the distant, snow-covered Swiss mountains.

Settlement and language

Over the centuries, settlement increased gradually, as was typical for a forested region. Forests were cleared for, inter alia, agriculture, livestock and early industrial factories (charcoal works and glassworks) and the water mills used water power. Concentrations of settlement and immigration took place and not only in areas where minerals were found. In the mining area of the Lièpvrette valley, for example, there was an influx of Saxon miners and mining specialists. From time to time, wars, plagues and religious conflicts saw the depopulation of territories – in their wake it was not uncommon for people to be relocated there from other areas.

In pre-Roman times, the Vosges was empty of settlements or was colonized and dominated by the Celts. After the Roman era, Alemanni also settled in the east, and Franks in the northwest. Contrary to widespread belief, the main ridge of the Vosges coincided with the historical Roman-Germanic language boundary only in the southern Vosges. Old Romance (Altromanisch) is spoken east of the main ridge: in the valley of the Weiss around Lapoutroie, the valley of Lièpvrette (nowadays also called the Val d'Argent, i.e. "Valley of Silver"), parts of the canton of Villé valley (Vallée de Villé) and parts of the Bruche valley (Vallée de la Bruche). By contrast, those parts of the northern Vosges and the whole of the Wasgau, which lie north of the Breusch valley, fall within the Germanic-speaking area because, from Schirmeck the historical linguistic boundary turns to the northwest and runs between Donon and Mutzigfelsen heading for Sarrebourg (Saarburg). The Germanic areas of the Vosges mountains are part of the Alemannic dialect region and cultural area and, in the north, also part of the Frankish dialect region and cultural area. The Romanesque areas are part of the patois language region. For a long time the distribution of languages and dialects basically correlated with the pattern of settlement movements. However, the switch from German to French as the lingua franca which took place between the 17th and the 20th century across the whole of Alsace was not accompanied by any further significant movements of population.

History

The massif known in Latin as Vosago mons or Vosego silva, sometimes Vogesus mons, was extended to the vast woods covering the region. Later, German speakers referred to the same region as Vogesen or Wasgenwald.

On the lower heights and buttresses of the main chain on the Alsatian side are numerous castles, generally in ruins, testifying to the importance of this crucial crossroads of Europe, violently contested for centuries. At several points on the main ridge, especially at Sainte Odile above Ribeauvillé (German: Rappoltsweiler), are the remains of a wall of unmortared stone with tenons of wood, about 1.8 to 2.2 m (6 to 7 ft) thick and 1.3 to 1.7 m (4 to 6 ft) high, called the Mur Païen (Pagan Wall). It was used for defence in the Middle Ages and archaeologists are divided as to whether it was built by the Romans, or before their arrival.

During the French Revolutionary Wars, on 13 July 1794, the Vosges were the scene of the Battle of the Vosges.

From 1871 to 1918, they formed the main border line between France and the German Empire. The demarcation line stretched from the Ballon d'Alsace to Mont Donon with the lands east of it being incorporated into Germany as part of Alsace-Lorraine.

During the First World War, the Vosges were the scene of severe and almost continuous fighting.[3] And during the Second World War, in autumn 1944, they were the site of brief but sharp fighting between Franco-American and German forces.

In the late 20th century a wide area of the massif was included in two protected areas, the Parc naturel régional des Vosges du Nord (established in 1976) and the Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges (established in 1989).

On 20 January 1992 Air Inter Flight 148 crashed into the Vosges Mountains while circling to land at Strasbourg International Airport, killing 87 people.

Nature parks

Two nature parks lie within the Vosges: the Ballons des Vosges Nature Park and the Northern Vosges Regional Nature Park. The Northern Vosges Nature Park and the Palatinate Forest Nature Park on the German side of the border form the cross-border Palatinate Forest-North Vosges Biosphere Reserve.

See also

References and notes

- ↑ IGN maps available on Géoportail

- 1 2 3 Dickinson, Robert E (1964). Germany: A Regional and Economic Geography (2nd ed.). London: Methuen, p. 540. ASIN B000IOFSEQ.

- ↑

Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). "Vosges Mountains". Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Company.

Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). "Vosges Mountains". Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Company.

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vosges (mountains)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vosges (mountains)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

General texts:

- René Bastien, Histoire de Lorraine, éditions Serpenoise, Metz, 1991, 224 pages. ISBN 2-87692-088-3 (simple historic approach for children)

- Etienne Julliard, Atlas et géographie de l'Alsace et de la Lorraine, Flammarion, 1977, 288 pages (a geogropher's view of this part of France who gives theirs waters to Rhin)

- Robert Parisot, Histoire de Lorraine (Meurthe, Meuse, Moselle, Vosges), Tome 1 à 4 et index alphabétique général, Auguste Picard éditeur, Paris, 1924. Anastaltic impression in Belgium by the éditions Culture et Civilisation, Bruxelles, 1978. (large and more sophisticated evenemential history)

- Yves Sell (dir.), L'Alsace et les Vosges, géologie, milieux naturels, flore et faune, La bibliothèque du naturaliste, Delachaux et Niestlé, Lausanne, 1998, 352 pages. ISBN 2-603-01100-6 (global view of nature and land)

- Jean-Paul von Eller, Guide géologique Vosges-Alsace, guide régionaux, collection dirigée par Charles Pomerol, 2° édition, Masson, Paris, 1984, 184 pages. ISBN 2-225-78496-5 (a precise geologic description)

List of majors periodicals concerning Lorraine and South Lorraine:

- Annales de l'Est (et du Nord), Nancy.

- Annales de la Société d'Émulation des Vosges, Epinal, from 1826.

- Bulletin de la Société Philomatique Vosgienne, Saint-Dié, from 1875 to 1999 (nowadays Mémoire des Vosges Histoire Société Coutumes)

- Publications of the Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie lorraine, Metz (from 1890, nowadays Les Cahiers Lorrains, trimestrial review).

- Publications of the Société d'Histoire de la Lorraine & Musée Lorrain, Nancy (Lotharingist wrintings since 1820, nowadays trimestrial périodical, Le Pays Lorrain)

On the First World War:

- Guide des sources de la Grande Guerre dans le département des Vosges, Conseil général de Vosges, Epinal, 2008, 296 pages. ISBN 978-2-86088-062-6

- Isabelle Chave (dir.) avec Magali Delavenne, Jean-Claude Fombaron, Philippe Nivet, Yann Prouillet, La Grande Guerre dans les Vosges : sources et état des lieux, Actes du colloque tenu à Epinal du 4 au 6 septembre 2008, Conseil général des Vosges, 2009, 348 pages. ISBN 978-2-86088-067-1

- "La guerre aérienne dans les Vosges. 1914–1919", Mémoire des Vosges H.S.C. édité par la Société Philomatique Vosgienne, [hors série n°5, septembre 2009], 68 pages. ISSN 1626-5238

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vosges mountains. |

- Illustrated article on the Vosges battlefields of WWI at Battlefields Europe at the Wayback Machine (archived 20 April 2012)