Masculinity

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Masculism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Topics and issues

|

||||

|

By country

|

||||

|

Notable persons |

||||

|

Lists and categories

|

||||

|

| ||||

Masculinity (also called boyhood, manliness, or manhood) is a set of attributes, behaviors and roles generally associated with boys and men. Masculinity is both socially-defined and biologically-created.[1][2][3] It is distinct from the definition of the male biological sex.[4][5] Both males and females can exhibit masculine traits and behavior. Those exhibiting both masculine and feminine characteristics are considered androgynous, and feminist philosophers have argued that gender ambiguity may blur gender classification.[6][7]

Traits traditionally cited as masculine include courage, independence and assertiveness.[8][9][10] These traits vary by location and context, and are influenced by social and cultural factors.[11] An overemphasis on masculinity and power, often associated with a disregard for consequences and responsibility, is known as machismo.[12]

Overview

Masculine qualities, characteristics or roles are considered typical of, or appropriate for, a boy or man. They have degrees of comparison: "more masculine" and "most masculine", and the opposite may be expressed by "unmanly" or "epicene".[13] Similar to masculinity is virility (from the Latin vir, "man"). The concept of masculinity varies historically and culturally; although the dandy was seen as a 19th-century ideal of masculinity, he is considered effeminate by modern standards.[14] Masculine norms, as described in Ronald F. Levant's Masculinity Reconstructed, are "avoidance of femininity; restricted emotions; sex disconnected from intimacy; pursuit of achievement and status; self-reliance; strength and aggression, and homophobia."[15] These norms reinforce gender roles by associating attributes and characteristics with one gender.[16]

The academic study of masculinity received increased attention during the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the number of courses on the subject in the United States rising from 30 to over 300.[17] This has sparked investigation of the intersection of masculinity with other axes of social discrimination and concepts from other fields, such as the social construction of gender difference[18] (prevalent in a number of philosophical and sociological theories).

Development

In many cultures, displaying characteristics not typical of one's gender may be a social problem. In sociology, this labeling is known as gender assumptions and is part of socialization to meet the mores of a society. Non-standard behavior may be considered indicative of homosexuality, despite the fact that gender expression, gender identity and sexual orientation are widely accepted as distinct concepts.[19] When sexuality is defined in terms of object choice (as in early sexology studies), male homosexuality is interpreted as effeminacy.[20] Social disapproval of excessive masculinity may be expressed as "machismo"[12] or by neologisms such as "testosterone poisoning".[21]

The relative importance of socialization and genetics in the development of masculinity is debated. Although social conditioning is believed to play a role, psychologists and psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung believed that aspects of "feminine" and "masculine" identity are subconsciously present in all human males.[lower-alpha 1]

The historical development of gender roles is addressed by behavioural genetics, evolutionary psychology, human ecology, anthropology and sociology. All human cultures seem to encourage gender roles in literature, costume and song; examples may include the epics of Homer, the Hengist and Horsa tales and the normative commentaries of Confucius. More specialized treatments of masculinity may be found in the Bhagavad Gita and the bushidō of Hagakure.

Nature versus nurture

The extent to which masculinity is inborn or conditioned is debated. Genome research has yielded information about the development of masculine characteristics and the process of sexual differentiation specific to the human reproductive system. The testis determining factor (also known as SRY protein) on the Y chromosome, critical for male sexual development, activates the SOX9 protein.[22] SOX9 works with the SF1 protein to increase the level of anti-Müllerian hormone, repressing female development while activating and forming a feedforward loop with the FGF9 protein; this creates the testis cords and is responsible for sertoli cells, which aid in sperm production.[23] The activation of SRY halts the process of creating a female, beginning a chain of events leading to testicle formation, androgen production and a number of pre- and post-natal hormonal effects.

How a child develops gender identity is also debated. Some believe that masculinity is linked to the male body; in this view, masculinity is associated with male genitalia.[24]</ref> Others have suggested that although masculinity may be influenced by biology, it is also a cultural construct. Recent research has been done on one's self concept of masculinity and its relation to testosterone; the results have shown that masculinity not only differs in different cultures, but the levels of testosterone do not predict how masculine or feminine one feels.[25] Proponents of this view argue that women can become men hormonally and physically,[24] and many aspects of masculinity assumed to be natural are linguistically and culturally driven.[26] On the nurture side of the debate, it is argued that masculinity does not have a single source. Although the military has a vested interest in constructing and promoting a specific form of masculinity, it does not create it.[27] Facial hair is linked to masculinity through language, in stories about boys becoming men when they begin to shave.[28]

Hegemonic masculinity

Traditional avenues for men to gain honor were providing for their families and exercising leadership.[29] Raewyn Connell has labeled traditional male roles and privileges hegemonic masculinity, encouraged in men and discouraged in women: "Hegemonic masculinity can be defined as the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees the dominant position of men and the subordination of women".[30] In addition to describing forceful articulations of violent masculine identities, hegemonic masculinity has also been used to describe implicit, indirect, or coercive forms of gendered socialisation, enacted through video games, fashion, humour, and so on.[31]

Precarious manhood

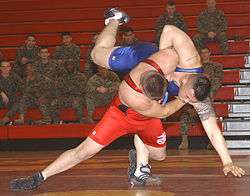

Researchers have argued that the "precariousness" of manhood contributes to traditionally-masculine behavior.[32] "Precarious" means that manhood is not inborn, but must be achieved. In many cultures, boys endure painful initiation rituals to become men. Manhood may also be lost, as when a man is derided for not "being a man." Researchers have found that men respond to threats to their manhood by engaging in stereotypically-masculine behaviors and beliefs, such as supporting hierarchy, espousing homophobic beliefs, supporting aggression and choosing physical tasks over intellectual ones.[33]

In 2014, Winegard and Geary wrote that the precariousness of manhood involves social status (prestige or dominance), and manhood may be more (or less) precarious due to the avenues men have for achieving status.[34] Men who identify with creative pursuits, such as poetry or painting, may not experience manhood as precarious but may respond to threats to their intelligence or creativity. However, men who identify with traditionally-masculine pursuits (such as football or the military) may see masculinity as precarious. According to Winegard, Winegard, and Geary, this is functional; poetry and painting do not require traditionally-masculine traits, and attacks on those traits should not induce anxiety. Football and the military require traditionally-masculine traits, such as pain tolerance, endurance, muscularity and courage, and attacks on those traits induce anxiety and may trigger retaliatory impulses and behavior. This suggests that nature-versus-nurture debates about masculinity may be simplistic. Although men evolved to pursue prestige and dominance (status), how they pursue status depends on their talents, traits and available possibilities. In modern societies, more avenues to status may exist than in traditional societies and this may mitigate the precariousness of manhood (or of traditional manhood); however, it will probably not mitigate the intensity of male-male competition.

In women

Although often ignored in discussions of masculinity, women can also express masculine traits and behaviors.[35][36] In Western culture, female masculinity has been codified into identities such as "tomboy" and "butch". Although female masculinity is often associated with lesbianism, expressing masculinity is not necessarily related to a woman's sexuality. In feminist philosophy, female masculinity is often characterized as a type of gender performance which challenges traditional masculinity and male dominance.[37] Masculine women are often subject to social stigma and harassment, although the influence of the feminist movement has led to greater acceptance of women expressing masculinity in recent decades.[38]

Health

Evidence points to the negative impact of hegemonic masculinity on men's health-related behavior, with American men making 134.5 million fewer physician visits per year than women. Men make 40.8 percent of all physician visits, including women's obstetric and gynecological visits. Twenty-five percent of men aged 45 to 60 do not have a personal physician, increasing their risk of death from heart disease. Men between 25 and 65 are four times more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than women, and are more likely to be diagnosed with a terminal illness because of their reluctance to see a doctor. Reasons cited for not seeing a physician include fear, denial, embarrassment, a dislike of situations out of their control and the belief that visiting a doctor is not worth the time or cost.[39]

Studies of men in North America and Europe show that men who consume alcoholic drinks often do so in order to fulfill certain social expectations of manliness. While the causes of drinking and alcoholism are complex and varied, gender roles and social expectations have a strong influence encouraging men to drink.[40][41]

In 2004, Arran Stibbe published an analysis of a well-known men's-health magazine in 2000. According to Stibbe, although the magazine ostensibly focused on health it also promoted traditional masculine behaviors such as excessive consumption of convenience foods and meat, alcohol consumption and unsafe sex.[42]

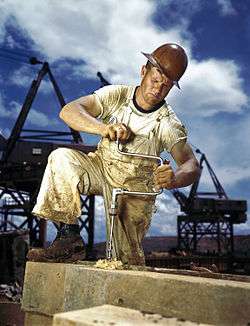

Research on beer-commercial content by Lance Strate[43] yielded results relevant to a study of masculinity.[44] In beer commercials, masculine behavior (especially risk-taking) is encouraged. Commercials often focus on situations in which a man overcomes an obstacle in a group, working or playing hard (construction or farm workers or cowboys). Those involving play have central themes of mastery (of nature or each other), risk and adventure: fishing, camping, playing sports or socializing in bars. There is usually an element of danger and a focus on movement and speed (watching fast cars or driving fast). The bar is a setting for the measurement of masculinity in skills such as billiards, strength, and drinking ability.

History

Since what constitutes masculinity has varied by time and place, according to Raewyn Connell, it is more appropriate to discuss "masculinities" than a single overarching concept.[45] Study of the history of masculinity emerged during the 1980s, aided by the fields of women’s and (later) gender history. Before women’s history was examined, there was a "strict gendering of the public/private divide"; regarding masculinity, this meant little study of how men related to the household, domesticity and family life.[46] Although women’s historical role was negated, despite the writing of history by (and primarily about) men a significant portion of the male experience was missing. This void was questioned during the late 1970s, when women’s history began to analyze gender and women to deepen the female experience.[47] Joan Scott’s seminal article, calling for gender studies as an analytical concept to explore society, power and discourse, laid the foundation for this field.[48] According to Scott gender should be used in two ways: productive and produced. Productive gender examined its role in creating power relationships, and produced gender explored the use and change of gender throughout history. This has influenced the field of masculinity, as seen in Pierre Bourdieu’s definition of masculinity: produced by society and culture, and reproduced in daily life.[49] A flurry of work in women’s history led to a call for study of the male role (initially influenced by psychoanalysis) in society and emotional and interpersonal life. Connell wrote that these initial works were marked by a "high level of generality" in "broad surveys of cultural norms". The scholarship was aware of contemporary societal changes aiming to understand and evolve (or liberate) the male role in response to feminism.[50] John Tosh calls for a return to this aim for the history of masculinity to be useful, academically and in the public sphere.[51]

Antiquity

.jpg)

Ancient literature dates back to about 3000 BC, with explicit expectations for men in the form of laws and implied masculine ideals in myths of gods and heroes. In the Hebrew Bible of 1000 BC, King David of Israel told his son to "be strong, and be a man" after David's death. Throughout history, men have met exacting cultural standards. Kate Cooper wrote about ancient concepts of femininity, "Wherever a woman is mentioned a man's character is being judged – and along with it what he stands for."[52] According to the Code of Hammurabi (about 1750 BC):

- Rule 3: "If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death."

- Rule 128: "If a man takes a woman to wife, but has no intercourse with her, this woman is no wife to him."[53]

Scholars cite integrity and equality as masculine values in male-male relationships[54] and virility in male-female relationships. Legends of ancient heroes include the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The stories demonstrate qualities in the hero which inspire respect, such as wisdom and courage: knowing things other men do not know and taking risks other men would not dare.

Medieval and Victorian eras

Jeffrey Richards describes a European "medieval masculinity which was essentially Christian and chivalric."[55] Courage, respect for women of all classes and generosity characterize the portrayal of men in literary history. The Anglo-Saxons Hengest and Horsa and Beowulf are examples of medieval masculine ideals. According to David Rosen, the traditional view of scholars (such as J. R. R. Tolkien) that Beowulf is a tale of medieval heroism overlooks the similarities between Beowulf and the monster Grendel. The masculinity exemplified by Beowulf "cut[s] men off from women, other men, passion and the household".[56]

During the Victorian era, masculinity underwent a transformation from traditional heroism. Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1831: "The old ideal of Manhood has grown obsolete, and the new is still invisible to us, and we grope after it in darkness, one clutching this phantom, another that; Werterism, Byronism, even Brummelism, each has its day".[57]

Present day

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a traditional family consisted of the father as breadwinner and the mother as homemaker. Characteristic of present-day masculinity is men's willingness to counter stereotypes. Regardless of age or nationality, men more frequently rank good health, a harmonious family life and a good relationship with their spouse or partner as important to their quality of life.[58]

Effeminacy

Gay men are considered by some to "deviate from the masculine norm" and are benevolently stereotyped as "gentle and refined", even by other gay men. According to gay human-rights campaigner Peter Tatchell:

Contrary to the well-intentioned claim that gays are "just the same" as straights, there is a difference. What is more, the distinctive style of gay masculinity is of great social benefit. Wouldn't life be dull without the flair and imagination of queer fashion designers and interior decorators? How could the NHS cope with no gay nurses, or the education system with no gay teachers? Society should thank its lucky stars that not all men turn out straight, macho and insensitive. The different hetero and homo modes of maleness are not, of course, biologically fixed.[59]

Psychologist Joseph Pleck argues that a hierarchy of masculinity exists largely as a dichotomy of homosexual and heterosexual males: "Our society uses the male heterosexual-homosexual dichotomy as a central symbol for all the rankings of masculinity, for the division on any grounds between males who are "real men" and have power, and males who are not".[60] Michael Kimmel adds that the trope "You're so gay" indicates a lack of masculinity, rather than homosexual orientation.[61] According to Pleck, to avoid male oppression of women, themselves and other men, patriarchal structures, institutions and discourse must be eliminated from Western society.

In the documentary The Butch Factor, gay men (one of them transgender) were asked about their views of masculinity. Masculine traits were generally seen as an advantage in and out of the closet, allowing "butch" gay men to conceal their sexual orientation longer while engaged in masculine activities such as sports. Effeminacy is inaccurately[19] associated with homosexuality,[20] and some gay men doubted their sexual orientation; they did not see themselves as effeminate, and felt little connection to gay culture.[62] Some effeminate gay men in The Butch Factor felt uncomfortable about their femininity (despite being comfortable with their sexuality),[63] and feminine gay men may be derided by stereotypically-masculine gays.[64]

Feminine-looking men tended to come out earlier after being labeled gay by their peers. More likely to face bullying and harassment throughout their lives,[62] they are taunted by derogatory words (such as "sissy") implying feminine qualities. Effeminate, "campy" gay men sometimes use what John R. Ballew called "camp humor", such as referring to one another by female pronouns (according to Ballew, "a funny way of defusing hate directed toward us [gay men]"); however, such humor "can cause us [gay men] to become confused in relation to how we feel about being men."[65] He further stated:

[Heterosexual] men are sometimes advised to get in touch with their "inner feminine." Maybe gay men need to get in touch with their "inner masculine" instead. Identifying those aspects of being a man we most value and then cultivate those parts of our selves can lead to a healthier and less distorted sense of our own masculinity.[65]

A study by the Center for Theoretical Study at Charles University in Prague and the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic found "significant" differences in shape among the faces of heterosexual and gay men, with gay men having "masculine" features ("undermin[ing] stereotypical notions of gay men as more feminine looking.")[66]

Gay men have been presented in the media as feminine and open to ridicule, although films such as Brokeback Mountain are countering the stereotype.[65] A recent development is the portrayal of gay men in the LGBT community as "bears", a subculture of gay men celebrating rugged masculinity[67][68] and "secondary sexual characteristics of the male: facial hair, body hair, proportional size, baldness".[69]

Second-wave pro-feminism paid greater attention to issues of sexuality, particularly the relationship between homosexual men and hegemonic masculinity. This shift led to increased cooperation between the men's liberation and gay liberation movements developing, in part, because masculinity was understood as a social construct and in response to the universalization of "men" in previous men's movements. Men's-rights activists worked to stop second-wave feminists from influencing the gay-rights movement, promoting hypermasculinity as inherent to gay sexuality.[70]

Masculinity has played an important role in lesbian culture,[71] although lesbians vary widely in the degree to which they express masculinity and femininity. In LGBT cultures, masculine women are often referred to as "butch".[72][73][74]

Criticism

Two concerns over the study of the history of masculinity are that it would stabilize the historical process (rather than change it) and that a cultural overemphasis on the approach to masculinity lacks the reality of actual experience. According to John Tosh, masculinity has become a conceptual framework used by historians to enhance their cultural explorations instead of a specialty in its own right.[75] This draws attention from reality to representation and meaning, not only in the realm of masculinity; culture was becoming "the bottom line, the real historical reality."[51] Tosh critiques Martin Francis' work of in this light because popular culture, rather than the experience of family life, is the basis for Francis’ argument.[76] Francis uses contemporary literature and film to demonstrate that masculinity was restless, shying away from domesticity and commitment, during the late 1940s and 1950s.[76] Francis wrote that this flight from commitment was "most likely to take place at the level of fantasy (individual and collective)." In focusing on culture, it is difficult to gauge the degree to which films such as Scott of the Antarctic represented the era’s masculine fantasies.[76] Michael Roper’s call to focus on the subjectivity of masculinity addresses this cultural bias, because broad understanding is set aside for an examination "of what the relationship of the codes of masculinity is to actual men, to existential matters, to persons and to their psychic make-up" (Tosh's human experience).[77]

According to Tosh, the culture of masculinity has outlived its usefulness because it cannot fulfill the initial aim of this history (to discover how manhood was conditioned and experienced) and he urged "questions of behaviour and agency".[75] His work on Victorian masculinity uses individual experience in letters and sketches to illustrate broader cultural and social customs, such as birthing or Christmas traditions.[46]

Stefan Dudink believes that the methodological approach (trying to categorize masculinity as a phenomenon) undermined its historiographic development.[78] Abigail Solomou-Godeau’s work on post-revolutionary French art addresses a strong, constant patriarchy.[79]

Tosh’s overall assessment is that a shift is needed in conceptualizing the topic[75] back to the history of masculinity as a speciality aiming to reach a broader audience, rather than as an analytical tool of cultural and social history. The importance he places on public history hearkens back to the initial aims of gender history, which sought to use history to enlighten and change the present. Tosh appeals to historians to live up to the "social expectation" of their work,[75] which would also require a greater focus on subjectivity and masculinity. This view is contrary to Dudink’s; the latter called for an "outflanking movement" towards the history of masculinity, in response to the errors he perceived in the study.[78] This would do the opposite of what Tosh called for, deconstructing masculinity by not placing it at the center of historical exploration and using discourse and culture as indirect avenues towards a more-representational approach. In a study of the Low Countries, Dudink proposes moving beyond the history of masculinity by embedding analysis into the exploration of nation and nationalism (making masculinity a lens through which to view conflict and nation-building).[80] Martin Francis' work on domesticity through a cultural lens moves beyond the history of masculinity because "men constantly travelled back and forward across the frontier of domesticity, if only in the realm of the imagination"; normative codes of behavior do not fully encompass the male experience.[76]

Media images of boys and young men may lead to the persistence of harmful concepts of masculinity. According to men's-rights activists, the media does not address men's-rights issues and men are often portrayed negatively in advertising.[81] Peter Jackson called hegemonic masculinity "economically exploitative" and "socially oppressive": "The form of oppression varies from patriarchal controls over women's bodies and reproductive rights, through ideologies of domesticity, femininity and compulsory heterosexuality, to social definitions of the value of work, the nature of skill and the differential remuneration of 'productive' and 'reproductive' labor."[82]

Psychological research

According to a paper submitted by Tracy Tylka to the American Psychological Association, "Instead of seeing a decrease in objectification of women in society, there has just been an increase in the objectification of both sexes. And you can see that in the media today." Men and women restrict food intake in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively-thin body; in extreme cases, this leads to eating disorders.[83] Psychiatrist Thomas Holbrook cited a recent Canadian study indicating that as many as one in six people with eating disorders are men.[84]

Research in the United Kingdom found, "Younger men and women who read fitness and fashion magazines could be psychologically harmed by the images of perfect female and male physiques." Young women and men exercise excessively in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively-fit and muscular body, which may lead to body dysmorphic disorder or muscle dysmorphia.[85][86][87] Although the stereotypes may have remained constant, the value attached to masculine stereotypes has changed; it has been argued that masculinity is an unstable phenomenon, never ultimately achieved.[28]

Gender-role stress

In 1987 Eisler and Skidmore studied masculinity, creating the idea of "masculine stress" and finding three elements of masculinity which often result in emotional stress:

- The emphasis on prevailing in situations requiring body and fitness

- Being perceived as emotional

- The need for adequacy in sexual matters and financial status

Because of social norms and pressures associated with masculinity, men with spinal-cord injuries must adapt their self-identity to the losses associated with such injuries; this may "lead to feelings of decreased physical and sexual prowess with lowered self-esteem and a loss of male identity. Feelings of guilt and overall loss of control are also experienced."[88] Research also suggests that men feel social pressure to endorse traditional masculine male models in advertising. Brett Martin and Juergen Gnoth (2009) found that although feminine men privately preferred feminine models, they expressed a preference for traditional masculine models in public; according to the authors, this reflected social pressure on men to endorse traditional masculine norms.[89]

In their book Raising Cain: Protecting The Emotional Life of Boys, Dan Kindlon and Michael Thompson wrote that although all boys are born loving and empathic, exposure to gender socialization (the tough male ideal and hypermasculinity) limits their ability to function as emotionally-healthy adults. According to Kindlon and Thompson, boys lack the ability to understand and express emotions productively because of the stress imposed by masculine gender roles.[90]

In the article "Sexual Ethics, Masculinity and Mutual Vulnerability," Rob Cover works to unpack Judith Butler's study of masculinity. Cover goes over issues such as sexual assault and how it can be partially explained by a hypermasculinity.[91]

"Masculinity in crisis"

A theory of "masculinity in crisis" has emerged;[92][93] Australian archeologist Peter McAllister said, "I have a strong feeling that masculinity is in crisis. Men are really searching for a role in modern society; the things we used to do aren't in much demand anymore".[94] Others see the changing labor market as a source of stress. Deindustrialization and the replacement of smokestack industries by technology have allowed more women to enter the labor force, reducing its emphasis on physical strength.[95]

The crisis has also been attributed to feminism and its questioning of male dominance and rights granted to men solely on the basis of sex.[96] British sociologist John MacInnes wrote that "masculinity has always been in one crisis or another", suggesting that the crises arise from the "fundamental incompatibility between the core principle of modernity that all human beings are essentially equal (regardless of their sex) and the core tenet of patriarchy that men are naturally superior to women and thus destined to rule over them."[97]

According to John Beynon, masculinity and men are often conflated and it is unclear whether masculinity, men or both are in crisis. He writes that the "crisis" is not a recent phenomenon, illustrating several periods of masculine crisis throughout history (some predating the women's movement and post-industrial society), suggesting that due to masculinity's fluid nature "crisis is constitutive of masculinity itself."[98] Film scholar Leon Hunt also writes: "Whenever masculinity's 'crisis' actually started, it certainly seems to have been in place by the 1970s".[99]

Herbivore men

In 2008, the word "herbivore men" became popular in Japan and was reported worldwide. Herbivore men refers to young Japanese men who naturally detach themselves from masculinity. Masahiro Morioka characterizes them as men 1) having gentle nature, 2) not bound by manliness, 3) not aggressive when it comes to romance, 4) viewing women as equals, and 5) hating emotional pain. Herbivore men was severely criticized by men who love masculinity.[100]

See also

- Bear (gay culture)

- Bromance

- Castro clone

- Emasculation

- Gender role

- Gender roles in non-heterosexual communities

- Hegemonic masculinity

- Leather subculture

- Male privilege

- Men's spaces

- Men's liberation

- Men's rights

- Men's movement

- Men's World Day

- Model of masculinity under fascist Italy

- Mythopoetic men's movement

- Raewyn Connell

- Victorian masculinity

Notable works on masculinity

- Absent fathers, lost sons, Guy Corneau, 1985.

- Manhood: a new definition, Stephen A. Shapiro, 1984.

- Female Masculinity, J. Halberstam, 1998.

- Wild at heart, John Eldredge, 2001.

- The new manhood, Steve Biddulph, 2010.

Notes

- ↑ See innate bisexuality and anima and animus for more information.

- ↑ Marianne van den Wijngaard (1997). Reinventing the sexes: the biomedical construction of femininity and masculinity. Race, gender, and science. Indiana University Press. pp. 171 pages. ISBN 0-253-21087-9. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ Hale Martin, Stephen Edward Finn (2010). Masculinity and Femininity in the MMPI-2 and MMPI-A. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 310 pages. ISBN 0-8166-2445-3. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ Richard Dunphy (2000). Sexual politics: an introduction. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 240 pages. ISBN 0-7486-1247-5. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ Ferrante, Joan. Sociology: A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 269–272. ISBN 0-8400-3204-8.

- ↑ Gender, Women and Health: What do we mean by "sex" and "gender"?', The World Health Organization

- ↑ Butler, Judith (1999 [1990]), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York and London: Routledge).

- ↑ Laurie, Timothy (2014). "The ethics of nobody I know: gender and the politics of description". Qualitative Research Journal. Emerald. 14 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1108/QRJ-03-2014-0011. Pdf.

- ↑ Vetterling-Braggin, Mary "Femininity," "masculinity," and "androgyny": a modern philosophical discussion

- ↑ Worell, Judith, Encyclopedia of women and gender: sex similarities and differences and the impact of society on gender, Volume 1 Elsevier, 2001, ISBN 0-12-227246-3, ISBN 978-0-12-227246-2

- ↑ Thomas, R. Murray (2000). Recent Theories of Human Development. Sage Publications. p. 248. ISBN 0761922474.

Gender feminists also consider traditional feminine traits (gentleness, modesty, humility, sacrifice, supportiveness, empathy, compassion, tenderness, nurturance, intuitiveness, sensitivity, unselfishness) morally superior to the traditional masculine traits (courage, strong will, ambition, independence, assertiveness, initiative, rationality and emotional control).

- ↑ Witt, edited by Charlotte (2010). Feminist Metaphysics: Explorations in the Ontology of Sex, Gender and Identity. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 77. ISBN 90-481-3782-9.

- 1 2 "Machismo (exaggerated masculinity) - Encyclopædia Britannica" (online ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Roget’s II: The New Thesaurus, 3rd. ed., Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

- ↑ Reeser (2010), pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Levant, Ronald F.; Kopecky, Gini (1995). Masculinity Reconstructed: Changing the Rules of Manhood—At Work, in Relationships, and in Family Life. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0452275416.

- ↑ Dornan, Jennifer (2004). "Blood from the Moon:Gender Ideology and the Rise of Ancient Maya Social Complexity". ISSN 0953-5233.

- ↑ Bradley, Rolla M. (2008). Masculinity and Self Perception of Men Identified as Informal Leaders. ProQuest. p. 9. ISBN 0549473998.

- ↑ Flood, Michael (2007). International Encyclopaedia of Men and Masculinities. Routledge. pp. Viii. ISBN 0415333431.

- 1 2 "Gender Identity and Expression Issues at Colleges and Universities". National Association of College and University Attorneys. 2 June 2005. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- 1 2 Associated Press (7 April 2006). "Chrysler TV ad criticized for using gay stereotypes". The Advocate. Here Press. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ↑ Alda, Alan (October 1975). "What every woman should know about men". Ms. New York.

- ↑ Moniot, Brigitte; Declosmenil, Faustine; Barrionuevo, Francisco; Scherer, Gerd; Aritake, Kosuke; Malki, Safia; Marzi, Laetitia; Cohen-Solal, Ann; Georg, Ina; Klattig, Jürgen; Englert, Christoph; Kim, Yuna; Capel, Blanche; Eguchi, Naomi; Urade, Yoshihiro; Boizet-Bonhoure, Brigitte; Poulat, Francis (2009). "The PGD2 pathway, independently of FGF9, amplifies SOX9 activity in Sertoli cells during male sexual differentiation". Development. The Company of Biologists Ltd. 136 (11): 1813–1821. PMID 19429785. doi:10.1242/dev.032631.

- ↑ Kim, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Sekido, R.; Dinapoli, L.; Brennan, J.; Chaboissier, M. C.; Poulat, F.; Behringer, R. R.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Capel, B. (2006). "Fgf9 and Wnt4 Act as Antagonistic Signals to Regulate Mammalian Sex Determination". PLoS Biology. Public Library of Science. 4 (6): e187. PMC 1463023

. PMID 16700629. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040187.

. PMID 16700629. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040187. - 1 2 Reeser (2010), p. 3.

- ↑ Pletzer, Belinda; Petasis, Ourania; Ortner, Tuulia M.; Cahill, Larry (2015). "Intereactive effects of culture and sex hormones on the role of self concept". Neuroendocrine Science. Frontiers Media. 9 (240): 1–10. PMC 4500910

. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00240.

. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00240. - ↑ Mills, Sara. "Third wave feminist linguistics and the analysis of sexism." Discourse analysis online 2.1 (2003).

- ↑ Reeser (2010), pp. 17–21.

- 1 2 Reeser (2010), pp. 30–31.

- ↑ George, A., "Reinventing honorable masculinity" Men and Masculinities

- ↑ Connell (2005), p. 77.

- ↑ Laurie, Timothy; Hickey-Moody, Anna (2017), "Masculinity and Ridicule", Gender: Laughter, Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference: 215–228

- ↑ Bosson, Jennifer K.; Vandello, Joseph A. (April 2011). "Precarious manhood and its links to action and aggression". Current Directions in Psychological Science. Sage. 20 (2): 82–86. doi:10.1177/0963721411402669.

- ↑ Vandello, Joseph A.; Bosson, Jennifer K.; Cohen, Dov; Burnaford, Rochelle M.; Weaver, Jonathan R. (December 2008). "Precarious manhood". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. PsycNET. 95 (6): 1325–1339. doi:10.1037/a0012453.

- ↑ Winegard, Bo M.; Winegard, Ben; Geary, David C. (March 2014). "Eastwood’s brawn and Einstein’s brain: an evolutionary account of dominance, prestige, and precarious manhood". Review of General Psychology. PsycNET. 18 (1): 34–48. doi:10.1037/a0036594.

- ↑ Keith, Thomas (2017). Masculinities in Contemporary American Culture: An Intersectional Approach to the Complexities and Challenges of Male Identity. New York: Routledge. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-31-759534-2.

- ↑ Halberstam, Judith (1998). Female Masculinity. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. xi–. ISBN 0-82-232243-9.

- ↑ Gardiner, Judith Kegan (December 2009). "Female masculinities: a review essay". Men and Masculinities. 11 (5): 622–633. doi:10.1177/1097184X08328448.

- ↑ Girshick, Lori B. (2008). Transgender Voices: Beyond Women and Men. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-58-465683-8.

- ↑ Galdas, Paul M.; Cheater, Francine M.; Marshall, Paul (March 2005). "Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review". Journal of Advanced Nursing. Wiley. 49 (6): 616–623. PMID 15737222. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x.

- ↑ Lemle, R; Mishkind, ME (1989). "Alcohol and masculinity". Journal of substance abuse treatment. 6 (4): 213–22. PMID 2687480. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(89)90045-7.

- ↑ Berkowitz, Alan D. (2004). "Alcohol". In Kimmel, Michael S.; Aronson, Amy. Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia: Volume 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9781576077740.

- ↑ Stibbe, Arran (July 2004). "Health and the social construction of masculinity in "Men's Health" magazine". Men and Masculinities. 7 (1): 31–51. doi:10.1177/1097184X03257441.

- ↑ Postman, Nystrom, Strate, And Weingartner 1987; Strate 1989, 1990 and Wenner 1991

- ↑ Strate (2001).

- ↑ Connell (2005), p. 185.

- 1 2 Tosh, John (1999). A Man's Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-30-007779-3.

- ↑ Davis, Natalie Z. (Spring–Summer 1976). ""Women's history" in transition: the European case". Feminist Studies. Feminist Studies, Inc. 3 (3–4): 83–103. JSTOR 3177729. doi:10.2307/3177729.

- ↑ Scott, Joan W. (December 1986). "Gender: a useful category of historical analysis". The American Historical Review. Oxford Journals. 91 (5): 1053–1075. JSTOR 1864376. doi:10.1086/ahr/91.5.1053.

- ↑ Bourdieu, Pierre (2001). Masculini Domination. Cambridge.

- ↑ Connell (2005), p. 28.

- 1 2 Steedman, Carolyn (1992), "Culture, cultural studies and the historians", in Grossberg, Lawrence; Nelson, Cary; Treichler, Paula, Cultural studies, New York: Routledge, p. 617, ISBN 9780415903455.

- ↑ Cooper, Kate (1996). The Virgin and The Bride: Idealized Womanhood in Late Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 19.

- ↑ Hammurabi (1910). Hooker, Richard, ed. The Code of Hammurabi. L.W. King (translator). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Bassi, Karen (January 2001). "Acting like men: gender, drama, and nostalgia in Ancient Greece". Classical Philology. Chicago Journals. 96 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1086/449528.

- ↑ Richards, Jeffrey (1999). "From Christianity to Paganism: The New Middle Ages and the Values of 'Medieval' Masculinity". Cultural Values. Taylor and Francis. 3 (2): 213–234. doi:10.1080/14797589909367162.

- ↑ Rosen, David (1993). The Changing Fictions of Masculinity. University of Illinois Press. p. 11. ISBN 0252063090.

- ↑ Adams, James Eli (1995). Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Masculinity. Cornell University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0801482089.

- ↑ "Research and insights from Indiana University" (Press release). Indiana University. 26 August 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- See also: Sand, Michael S.; Fisher, William; Rosen, Raymond; Heiman, Julia; Eardley, Ian (March 2008). "Erectile dysfunction and constructs of masculinity and quality of life in the multinational Men's Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (MALES) study". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. Elsevier. 5 (3): 583–594. PMID 18221291. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00720.x.

- ↑ Tatchell, Peter (January 1999). "What Straight men Could Learn From Gay Men - A Queer Kind of Masculinity?". The Scavenger. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Pleck, Joseph. "Understanding Patriarchy and Men's Power". National Organization for Men Against Sexism (NOMAS). Retrieved 11 Jan 2017.

- ↑ Kimmel, Michael S.; Lewis, Summer (2004). Mars and Venus, Or, Planet Earth?: Women and Men in a New Millenium [sic]. Kansas State University.

- 1 2 ifsbutscoconuts. "The Butch Factor: Masculinity from a Gay Male Perspective (blog)". Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Curry, Tyler. "The Strength in Being a Feminine Gay Man". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Darianna (7 July 2014). "Why Do Masculine Gay Guys Look Down On Feminine Guys?". Queerty. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

See also: Jones, Darianna (9 July 2014). "An Open Letter to Gay Guys Who Look Down On 'Fem Guys'". The Good Men Project. Retrieved 6 March 2015. - 1 2 3 Ballew, John R. "Gay men and masculinity (blog)". bodymindsoul.org. John R. Ballew. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Saul, Heather (8 November 2013). "Gay and straight men may have different facial shapes, new study suggests". The Independent. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

Their results found that homosexual men were rated as more stereotypically 'masculine' than heterosexual men, which they said undermined stereotypical notions of gay men as more feminine looking.

- ↑ advocate.com editors (17 April 2014). "When The Advocate Invented Bears". The Advocate. Here Media Inc. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Mazzei, George (1979). "Who's Who in the Zoo?". The Advocate. Here Media Inc. pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Suresha, Ron (2009). Bears on Bears: Interviews and Discussions. Lethe Press. p. 83. ISBN 1590212444.

- ↑ Jeffreys, Sheila (2003). Unpacking queer politics: a lesbian feminist perspective. Cambridge Malden, Massachusetts: Polity Press. ISBN 9780745628387.

- ↑ Halberstam, Judith (1998). Female Masculinity. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. p. 119. ISBN 0822322439.

- ↑ Wickens, Kathryn. "Welcome to our Butch-Femme Definitions Page (blog)". Butch–Femme Network, founded in Massachusetts in 1996. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Hollibaugh, Amber L. (2000). My Dangerous Desires: A Queer Girl Dreaming Her Way Home. Duke University Press. p. 249. ISBN 0822326191.

- ↑ Boyd, Helen (2004). My Husband Betty: Love, Sex and Life With a Cross-Dresser. Sdal Press. p. 64. ISBN 1560255153.

- 1 2 3 4 Tosh, John (2013). "The history of masculinity: an outdated concept?". In Arnold, John H.; Brady, Sean. What is masculinity? Historical dynamics from antiquity to the contemporary world. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-13-730560-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Francis, Martin (April 2007). "A flight from commitment? Domesticity, adventure and the masculine imaginary in Britain after the Second World War". Gender & History. Wiley. 19 (1): 163–185. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2007.00469.x.

- ↑ Roper, Michael (March 2005). "Slipping out of view: subjectivity and emotion in gender history". History Workshop Journal. Oxford Journals. 59 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbi006.

- 1 2 Dudink, Stefan (September 1998). "The trouble with men: Problems in the history of 'masculinity'". European Journal of Cultural Studies. Sage. 1 (3): 419–431. doi:10.1177/136754949800100307.

- ↑ Solomou-Godeau, Abigail (1997). Male Trouble: A Crisis in Representation. London.

- ↑ Dudink, Stefan (March 2012). "Multipurpose masculinities: gender and power in low countries histories of masculinity". BMGN: Low Countries Historical Review. Royal Netherlands Historical Society. 127 (1): 5–18. doi:10.18352/bmgn-lchr.1562.

- ↑ Farrell, W. & Sterba, J. P. (2008) Does Feminism Discriminate Against Men: A Debate (Point and Counterpoint), New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Jackson, Peter (April 1991). "The cultural politics of masculinity: towards a social geography". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Wiley. 16 (2): 199–213. JSTOR 622614. doi:10.2307/622614.

- ↑ Grabmeier, Jeff (10 August 2006). "Pressure to be more muscular may lead men to unhealthy behaviors". Ohio State University.

- ↑ Goode, Erica (25 June 2000). "Thinner: The Male Battle With Anorexia". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ "Magazines 'harm male body image'". BBC News. 28 May 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ "Muscle dysmorphia". AskMen.com.

- ↑ "Men muscle in on body image problems". livescience.com. LiveScience. 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Susan L.; Kleiber, Douglas A. (January 2000). "Heroic masculinity following spinal cord injury: Implications for therapeutic recreation practice and research". Therapeutic Recreation Journal. Sagamore Journals. 34 (1).

- ↑ Martin, Brett A.S.; Gnoth, Juergen (December 2009). "Is the Marlboro man the only alternative? The role of gender identity and self-construal salience in evaluations of male models". Marketing Letters. Springer. 20 (4): 353–367. doi:10.1007/s11002-009-9069-2. Pdf.

- ↑ Kindlon, Dan; Thompson, Michael (2000), "The road not taken: turning boys away from their inner life", in Kindlon, Dan; Thompson, Michael, Raising Cain: protecting the emotional life of boys, New York: Ballantine Books, pp. 1–20, ISBN 9780345434852.

- ↑ Cover, Rob (2014). "Sexual ethics, masculinity and mutual vulnerability: Judith Butler’s contribution to an ethics of non-violence". Australian Feminist Studies. Taylor and Francis. 29 (82): 435–451. doi:10.1080/08164649.2014.967741.

- ↑ Horrocks, Rooger (1994). Masculinities in Crisis: Myths, Fantasies, and Realities. St Martin's Press. ISBN 0333593227.

- ↑ Robinson, Sally (2000). Marked Men: White Masculinity in Crisis. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-231-50036-4.

- ↑ Rogers, Thomas (November 14, 2010). "The dramatic decline of the modern man". Salon. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ↑ Beynon (2002), pp. 86–89.

- ↑ Beynon (2002), pp. 83–86.

- ↑ MacInnes, John (1998). The end of masculinity: the confusion of sexual genesis and sexual difference in modern society. Philadelphia: Open University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-335-19659-3.

- ↑ Beynon (2002).

- ↑ Hunt, Leon (1998). British low culture: from safari suits to sexploitation. London, New York: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-415-15182-5.

- ↑ Morioka, Masahiro (September 2013). "A phenomenological study of "Herbivore Men"". The Review of Life Studies. 4: 1–20. Pdf.

References

- Beynon, John (2002), "Masculinities and the notion of 'crisis'", in Beynon, John, Masculinities and culture, Philadelphia: Open University Press, pp. 75–97, ISBN 978-0-335-19988-4

- Reeser, Todd W. (2010). Masculinities in theory: an introduction. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6859-5.

- Connell, R.W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 0-74-563427-3.

- Levine, Martin (1998). Gay macho: the life and death of the homosexual clone. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814746943.

- Strate, Lance (2001). "Beer commercials: a manual on masculinity". In Kimmel, Michael; Messner, Michael. Men's lives (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 9780205321056.

Further reading

Contemporary

- Arrindell, Willem A. (1 October 2005). "Masculine gender role stress". Psychiatric Times. XXII (11): 31.

- Arrindell, Willem A.; et al. (September–December 2003). "Masculine gender role stress: a potential predictor of phobic and obsessive-compulsive behaviour". Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 34 (3–4): 251–267. PMID 14972672. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2003.10.002.

- Ashe, Fidelma (2006). The New Politics of Masculinity : Men, Power and Resistance. City: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781281062505.

- Broom, Alex; Tovey, Philip, eds. (2009). Men's health: body, identity, and social context. Chichester, West Sussex, U.K. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470516560.

- Burstin, Fay (October 15, 2005). "What's killing men". Herald Sun. Melbourne.

- Courtenay, Will H. (May 2000). "Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health" (PDF). Social Science & Medicine. 50 (10): 1385–1401. PMID 10741575. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1.

- Durham, Meenakshi G.; Oates, Thomas P. (2004). "The mismeasure of masculinity: the male body, 'race' and power in the enumerative discourses of the NFL Draft". Patterns of Prejudice. 38 (3): 301–320. doi:10.1080/0031322042000250475.

- Evans, Joan; et al. (March 2011). "Health, Illness, Men and Masculinities (HIMM): a theoretical framework for understanding men and their health" (PDF). Journal of Men's Health. 8 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.jomh.2010.09.227.

- Galdas, Paul M.; Cheater, Francine M. (2010). "Indian and Pakistani men’s accounts of seeking medical help for cardiac chest pain in the United Kingdom: constructions of marginalised masculinity or another version of hegemonic masculinity?". Qualitative Research in Psychology. 7 (2): 122–139. doi:10.1080/14780880802571168.

- Juergensmeyer, Mark (2003). "Why Guys Throw Bombs" (PDF). Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence (౩rd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 198–. ISBN 0-52-024011-1.

- Hamber, Brandon (December 2007). "Masculinity and transitional justice: an exploratory essay". International Journal of Transitional Justice. 1 (3): 375–390. doi:10.1093/ijtj/ijm037.

- hooks, bell (2004). We real cool: Black men and masculinity. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415969277.

- Kimmel, Michael; Messner, Michael, eds. (2001). Men's lives (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 9780205321056.

- Lawson, Robert (2013). "The construction of ‘tough’ masculinity: Negotiation, alignment and rejection". Gender and Language. 7 (3): 369–395. doi:10.1558/genl.v7i3.369.

- Levant, Ronald F.; Pollack, William S., eds. (1995). A new psychology of men. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465039166.

- Levant, Ronald F.; Wong, Y. Joel (2017). The Psychology of Men and Masculinities. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-43-382690-0.

- Lupton, Ben (March 2006). "Explaining men's entry into female-concentrated occupations: issues of masculinity and social class". Gender, Work and Organization. John Wiley & Sons. 13 (2): 103–128. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2006.00299.x.

- Mansfield, Harvey (2006). Manliness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300106640.

- Masculinity for Boys: Resource Guide for Peer Educators (PDF). New Delhi: UNESCO. 2006. IN/2006/ED/4.

- Robinson, L. (October 21, 2005). "Not just boys being boys: Brutal hazings are a product of a culture of masculinity defined by violence, aggression and domination". Ottawa Citizen. Ottawa, Ontario.

- Stephenson, June (1995). Men are not cost-effective: male crime in America. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 9780060950989.

- Simpson, Mark (1994). Male impersonators: men performing masculinity. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 9780415909914.

- Also available as: Simpson, Mark (1993). Male impersonators: men performing masculinity. London: Cassell. ISBN 9780304328086.

- Shuttleworth, Russell (2004), "Disabled masculinity", in Smith, Bonnie G.; Hutchison, Beth, Gendering disability, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, pp. 166–178, ISBN 9780813533735

- Tozer, Malcolm (2015). The ideal of manliness: the legacy of Thring's Uppingham. Truro: Sunnyrest Books. ISBN 9781329542730.

- Walsh, Fintan (2010). Male trouble: masculinity and the performance of crisis. Basingstoke, Hampshire England New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781349368242.

- Williamson, P. (29 November 1995). "Their own worst enemy". Nursing Times. 91 (48): 24–27. OCLC 937998604.

- Wong, Y. Joel; et al. (2017). "Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes" (PDF). Journal of Counseling Psychology. 64 (1): 80–93. doi:10.1037/cou0000176.

- World Health Organization (2000). What About Boys?: A Literature Review on the Health and Development of Adolescent Boys (PDF). Geneva, Switzerland. WHO/FCH/CAH/00.7.

- Wray, Herbert (26 September 2005). "Survival skills". U.S. News & World Report. Vol. 139 no. 11. p. 63.

Historical

- Jenkins, Earnestine; Clark Hine, Darlene (1999). A question of manhood: a reader in U.S. Black men's history and masculinity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253213433.

- Kimmel, Michael (2012) [1996]. Manhood in America: A Cultural History (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199781553.

- Laurie, Ross (1999), "Masculinity", in Boyd, Kelly, Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing vol 2, Taylor & Francis, pp. 778–80, Historiography.

- Pleck, Elizabeth Hafkin; Pleck, Joseph H. (1980). The American man. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780130281425.

- Taylor, Gary (2002). Castration: an abbreviated history of western manhood. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415938815.

- Theweleit, Klaus (1987). Male fantasies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816614516.

- Stearns, Peter N. (1990). Be a man!: males in modern society. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 9780841912816.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Masculinity |

| Look up masculinity in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Bibliographic

- The Men's Bibliography, a comprehensive bibliography of writing on men, masculinities, gender and sexualities, listing over 16,700 works. (mainly from a constructionist perspective)

- Boyhood Studies, features a 2200+ bibliography of young masculinities.

Other

- The ManKind Project of Chicago, supporting men in leading meaningful lives of integrity, accountability, responsibility, and emotional intelligence

- NIMH web pages on men and depression, talks about men and their depression and how to get help.

- HeadsUpGuys, health strategies for managing and preventing depression in men.

- Article entitled "Wounded Masculinity: Parsifal and The Fisher King Wound" The symbolism of the story as it relates to the Wounded Masculinity of Men by Richard Sanderson M.Ed., B.A.

- BULL, print and online literary journal specializing in masculine fiction for a male audience.

- Art of Manliness, an online web magazine/blog dedicated to "reviving the lost art of manliness".

- The Masculinity Conspiracy, an online book critiquing constructions of masculinity.

- Men in America, series by National Public Radio