Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment

| Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment | |

|---|---|

|

Continental Army riflemen skirmishing with enemy troops at the Battle of Saratoga. Painting by H. Charles McBarron, Jr. | |

| Active | June 17, 1776 – January 1, 1781: organized June 17, 1776; reorganized January 23, 1779; disbanded January 1, 1781 |

| Country | United States of America |

| Branch | Continental Army |

| Type | Light Infantry |

| Size | ~420 officers and enlisted men in late 1776, 52 officers and enlisted men in late 1780 |

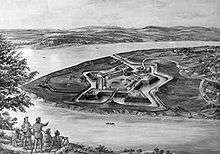

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Lee, Fort Washington, Fort Frederick, Fort Pitt |

| Nickname(s) | Stephenson's Rifle Regiment, Rawlings' (or Rawlins') Regiment, Maryland Corps, Maryland Rifle Corps, Maryland Independent Corps |

| Engagements | Battle of Fort Washington, Battle of Trenton, Battle of Princeton, Philadelphia Campaign (Battle of Brandywine, Battle of Germantown), Battle of Monmouth, and Brodhead Campaign. Detached elements participated in the Battles of Saratoga, Butler Campaign, and Sullivan Campaign. |

| Commanders | |

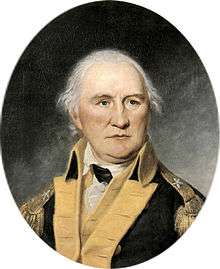

| First Commander | Col. Hugh Stephenson (June – September 1776) |

| Second Commander | Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings (September 1776 – June 1779) |

| Final Commanders | Capt. Thomas Beall (June 1779 – October 1780), Capt. Adamson Tannehill (October 1780 – January 1781) |

The Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment, most commonly known as Rawlings' Regiment in period documents, was organized in June 1776 as a specialized light infantry unit of riflemen in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. The American rifle units complemented the predominant, musket-equipped, line infantry forces of the war with their long-range marksmanship capability and were typically deployed with the line infantry as forward skirmishers and flanking elements. Scouting, escort, and outpost duties were also routine. The rifle units' battle formation was not nearly as structured as that of the line infantry units, which employed short-range massed firing in ordered linear formations. The riflemen could therefore respond with more adaptability to changing battle conditions.

The Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment consisted of nine companies—four from Maryland and five from Virginia. The two-state composition of the new unit precluded it from being managed through a single state government, and it was therefore directly responsible to national authority as an Extra Continental regiment.

Because most of the newly formed regiment surrendered to British and German forces at the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776, the service history of the unit's surviving element is complex. Although modern and contemporaneous accounts of the battle convey the impression that it marked the end of the regiment as a combat entity, a significant portion of the unit continued to serve actively in the Continental Army throughout most of the remainder of the war. Elements of the regiment served with George Washington's Main Army and participated in the army's major engagements of late 1776 through 1778. Select members of the regiment were also attached to Col. Daniel Morgan's elite Provisional Rifle Corps at its inception in mid-1777. The Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment was reorganized in January 1779 and was stationed at Fort Pitt, headquarters of the Continental Army's Western Department, in present-day western Pennsylvania primarily to help in the defense of frontier settlements from raids by British-allied Indian tribes. The unit was disbanded with all other Additional and Extra Continental regiments during the reorganization of the Continental Army in January 1781. It was the longest serving Continental Army rifle unit of the war.

Organization

During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress directed the organization of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment in resolves dated June 17 and 27, 1776.[3] The unit comprised three of the four independent Continental rifle companies that had formed in Maryland and Virginia by decree of Congress in mid-1775,[4] and six new companies—two from Maryland and four from Virginia. The three 1775 companies, among the first of the colonial units to join the newly constituted Continental Army, were raised and initially commanded by Capts. Michael Cresap, Thomas Price, and Hugh Stephenson.[5][6] The nine-company force became a regiment on the same tables of organization as the 1st Continental Regiment, which was originally the Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment.[7] Unlike this Pennsylvania unit, however, the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment was an Extra Continental regiment because of its two-state composition.[8] It was not part of a state line organization but was instead directly accountable to national authority (Congress and the Continental Army). The Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment's field officers were drawn from the original three 1775 companies based on their seniority. Hugh Stephenson from Virginia became the colonel, and Marylanders Moses Rawlings of Cresap's company[9] and Otho Holland Williams of Price's company[1] were designated the lieutenant colonel and major, respectively.[10] All company officers were appointed in the summer of 1776, and subsequent recruiting for the unit in the two states extended to the end of the year.[11] Recruiting occurred in Frederick and Harford Counties, Maryland, and Berkeley, Frederick, Loudoun, Fauquier, Prince William, and Culpeper Counties, Virginia.[12] The enlisted men of the regiment served for three years or the duration of the war.[10][13]

Battle of Fort Washington and surviving elements

By early November 1776, the majority of the regiment's officers and enlisted men had joined Washington's Main Army while it was engaged in the battle for New York City during the New York and New Jersey campaign.[14] They were initially stationed at Fort Washington on Manhattan Island and nearby Fort Lee on the opposite side of the Hudson River.[15] On November 16, most of the regiment was captured or killed during the Battle of Fort Washington.[16] The riflemen were defending the northern end of the American position from a much larger force of several thousand Hessian troops.[17][18] After heavy fighting that lasted most of the day and during which the Hessians suffered many casualties, the riflemen were eventually driven from the outer works into the fort where they and the rest of the outnumbered American garrison surrendered to the combined British and German attack force.[19] Lieutenant Colonel Rawlings was commanding the regiment during the battle because Colonel Stephenson had died of illness in August or September[20] and had not been replaced.[21] About 140 of the regiment's officers and enlisted men[22][23]—one-third of the unit's total complement of about 420 men[16][24]—were not present at the battle, however, because they were still completing organization and recruiting. A few enlisted men of the regiment who escaped from their captors within the short chaotic period following the battle augmented this remaining active force,[25] which continued to serve with the Main Army. On December 1, the first day of the army's next regular reporting period following the fall of Fort Washington, Washington provisionally grouped these remnants of the diminished regiment into two composite rifle companies commanded by the unit's highest ranking officers still free—Capts. Alexander Lawson Smith and Gabriel Long.[23][26] Smith's company comprised all the remaining Marylanders in the regiment, whereas the Virginians of the unit were placed under Long's command.

The regiment's two composite companies served with the Main Army during its retreat across New Jersey in late 1776,[27][28] in the ensuing Battles of Trenton and Princeton[29][30] in Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer's Brigade,[31][32] and in the early 1777 skirmishing in northern New Jersey, a period termed the Forage War.[33] While in winter quarters at Morristown during the winter and spring of 1777,[34] the two-company force and other riflemen from Pennsylvania and Virginia Line regiments[35] supported detached elements of line infantry units in front-line positions and conducted patrols in northern New Jersey,[36][37] primarily to keep the enemy's aggressive foraging activities in check. Because the two units under Captains Smith and Long provided an experienced, if small, force, Washington also used them to bolster the new 11th Virginia Regiment commanded by Col. Daniel Morgan after its arrival at Morristown in early April[38] by formally attaching them to this Virginia regiment.[23][26] Washington's decision to join the two composite companies with the 11th Virginia Regiment was based on Morgan's earlier direct association with the original three independent Continental rifle companies of 1775 that formed the core element of Rawlings' regiment.[21][39] Inasmuch as the attachment of one military unit to another was technically a temporary arrangement, however, the permanent unit of Smith's and Long's composite companies remained the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment.[40] The first muster rolls of the two companies taken after the Battle of Fort Washington, both dated May 16, 1777, were compiled by the army staff as a result of the attachment process and show that the units comprised about 110 officers and enlisted men on active duty in the spring of 1777.[22][23] The rolls also document that the units had lost a number of men over the winter months following the battle, primarily through desertion and a few deaths due to illness or wounds.

Attachment to Morgan's Provisional Rifle Corps

The success of these rifle units during the skirmishing period, coupled with the arrival of large numbers of new army recruits, led Washington to create additional provisional rifle companies. He placed them under the command of Daniel Morgan in early June 1777,[41] calling the unit the Provisional Rifle Corps, although it was most commonly known as Morgan's Rifle Corps in period documents. Morgan then simultaneously led the 11th Virginia Regiment, his permanent unit, and this provisional unit. Thirty-five officers and enlisted men in Smith's and Long's composite companies, as well as others selected from their regular musket regiments, were detached from their permanent units to form this elite regiment-sized force.[42] The men from the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment all served in one of the Rifle Corps' eight companies, Capt. Gabriel Long's Provisional Rifle Company; with the exception of a single man, all other members of the company came from the 11th Virginia Regiment.[43] Like Morgan, Long was now technically in command of two Continental Army units, one permanent and one provisional. Long served in the Rifle Corps until his resignation in May 1779,[44][45] at which time command of his company passed to Marylander Lt. Elijah Evans, also one of the original officers of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment.[16][46] Evans returned to Rawlings' regiment, his permanent unit, when his detached duty in the Rifle Corps ended with its formal disbanding in early November 1779.[47][48] The Rifle Corps is most notable for the major role it played in the Battles of Saratoga.[49]

Most members of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment, however, were not chosen for the Rifle Corps and remained with the Main Army. The Marylanders in Smith's composite company served with the 11th Virginia Regiment in the 3rd Virginia Brigade[50] at the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown, as well as at the Battle of Monmouth[51][52] after they were administratively attached to the 4th Maryland Regiment of the 2nd Maryland Brigade[53] at the end of the 1777 campaign season.[54] The Virginians in Long's composite company remained attached to the 11th Virginia Regiment and fought at the same engagements in 1777 and 1778.[51][55] Lt. (later Capt.) Philip Slaughter was the acting commander of the company during Long's nearly two-year attachment to the Rifle Corps and its permanent commander after Long's resignation.[56][57]

Fort Frederick and reorganization

.jpg)

Soon after Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings, a Marylander, was exchanged from British captivity in late December 1777 or January 1778,[58] the Board of War, at the request of the Maryland state government, assigned him command of the prisoner-of-war camp at Fort Frederick, Maryland, and its state militia guard.[59] The elements of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment in the field continued to be led by the company commanders until recruiting could bring the regiment up to greater strength. Maj. Otho Holland Williams, exchanged on January 16, 1778[60] (likely with Rawlings), had been promoted to colonel of the 6th Maryland Regiment in December 1776 while a prisoner of war; he took command of this unit upon his release.[61] The position of major in the reduced Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment was never refilled.

In the late spring of 1778, Rawlings began marshaling his regiment, including returning prisoners of war[16][62] and new recruits,[63][64] to reestablish its full complement. His efforts met with only limited success, however, despite Washington's request to Maryland governor Thomas Johnson in late December 1777 in anticipation of Rawlings' imminent exchange "that the most early and vigorous measures will be adopted, not only to make [Rawlings'] Regiment more respectable, but compleat [sic]."[65] Moreover, in early October 1778 Congress permitted Rawlings and his officers to recruit outside Maryland, with each new enlistee being officially entitled to the enlistment bonus and clothing allowance of his own state's line organization.[66] Implementation of this unusual ruling, however, added few men to the unit, reflecting the Continental Army's increasing difficulty in recruiting by this time of the war.[67] The few recruiting records for the unit that exist indicate that by the end of 1778, Rawlings' force of Continental regulars at Fort Frederick probably included no more than 30 to 40 new enlistees.[62][64]

Washington initiated more definitive measures to strengthen the regiment in early 1779. At his request,[68] Congress authorized on January 23 the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment to be reorganized into three companies, recruited to full strength, and reassigned from Fort Frederick to Fort Pitt, headquarters of the Continental Army's Western Department.[69] The reorganization, which was implemented on March 21,[70] served to supplement forces engaged in the defense of frontier settlements of present-day western Pennsylvania and vicinity from Indian raids that had started in early 1777. In mid-1778, after more than a year of these attacks, largely by warriors of British-allied Iroquois tribes and Loyalist forces, Washington commenced a concerted effort to neutralize the threat to the backcountry settlements of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—the war's western front.[71] In support of the reorganization process, on February 16, 1779, Washington ordered that all the regiment's detached members in the Main Army be reincorporated into the unit.[72] Pursuant to Washington's order, the enlisted men in Smith's composite company who were attached to the 4th Maryland Regiment rejoined Rawlings' command.[73] In contrast, the Virginians of Long's composite company already had been all but formally incorporated into the 11th Virginia Regiment by order of the Virginia state government in February 1777.[74] (Because Long's unit was a component of an Extra Continental regiment and therefore had no administrative connection to an individual state, the Virginia state government had exceeded its authority in this action, which was technically only within the purview of Congress. Washington tacitly accepted the arrangement, but the process was probably not formalized until the reorganization and redesignation of the 11th Virginia Regiment as the 7th Virginia Regiment on May 12, 1779.[51]) Moreover, the enlisted men of Smith's and Long's companies who were still attached to the Provisional Rifle Corps, which was not part of the Main Army at this time, remained in that unit until mid-1779, at which time they left the service because their three-year enlistment periods had expired.[46] Rawlings' force therefore now consisted of almost all Marylanders and was variously identified as the "Maryland Corps,"[75][76] "Maryland Rifle Corps,"[77][78] and "Maryland Independent Corps"[79][80] during its service on the western frontier. The unit, however, remained outside the state line organization, a source of great frustration for its officers.[81][82] Because no unit-redesignation orders accompanied the reorganization orders, the unit's formal name remained the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment despite significant variations from the unit's original 1776 configuration.[83]

Fort Pitt and the Western Department

After recruitment of the three companies had been no more than partially completed, Rawlings' regiment set off for Fort Pitt, arriving there in late May 1779.[84] The three companies consisted of about 100 enlisted men,[85] well below the prescribed total of about 60 enlisted men per company in a Continental Army line infantry regiment in 1779.[86] Moreover, a month after its arrival, the unit lost almost half of its troop strength[84] because the three-year enlistment periods of those men who had joined the regiment during its organization in mid-1776 had terminated. To further complicate matters, Rawlings resigned his command of the regiment on June 2,[87] primarily because of his frustration over not being able to fully rebuild the unit,[58] and did not accompany his men. He remained the commandant of Fort Frederick[88] and subsequently served as Deputy Commissary of Prisoners for Maryland.[87] Capt. Alexander Lawson Smith also did not proceed to Fort Pitt with the riflemen. He likely stayed with the 4th Maryland Regiment of the Main Army in a continued attached capacity until Congress approved his resignation from "the regiment formerly Rawlins [sic]" in September 1780.[89] The regiment was now commanded by senior captain Thomas Beall[47][80] and later Capt. Adamson Tannehill, both of whom had been with the unit since its inception.[90]

The Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment complemented the existing garrison at Fort Pitt: the 8th Pennsylvania and 9th (formerly 13th) Virginia Regiments.[91] The men of these Pennsylvania and Virginia line infantry units had been recruited from the central and western frontier counties of the two states and were assigned to the army's Western Department while at Valley Forge, reflecting a clear logic on Washington's part.[92] With the arrival of Rawlings' regiment, Western Department commander Col. Daniel Brodhead now led a force of largely frontier raised men experienced in Indian-style woodlands warfare. In his most notable tactical achievement, Brodhead headed a campaign of about 600 of his Continental regulars, which included the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment,[93][94] local militia, and volunteers to the upper waters of the Allegheny River in August and September 1779, where they destroyed the villages and crops of hostile Mingo and Munsee Indians.[95] Brodhead's expedition was part of Washington's wide-ranging, coordinated offensive of the summer of 1779 that also included the larger, concurrent Sullivan Campaign led by Maj. Gen. John Sullivan and Brig. Gen. James Clinton against enemy Iroquois and Loyalist units in southern and western New York State.[96] From mid-1779 until late 1780, however, the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment was primarily deployed in detachments to support line infantry contingents at several of the frontier outposts in the general vicinity of Fort Pitt, including Fort Laurens,[97] Fort McIntosh,[98] and Fort Henry (Wheeling)[99] in what is now eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, and northernmost West Virginia, respectively.

Change in command of the regiment occurred for the third time in late 1780. Under continual pressure to maintain sufficient troop strength in the unit, regimental commander Capt. Thomas Beall ran afoul of army regulations and Western Department commander Brodhead by approving the enlistment of a British prisoner of war in February 1780. Beall tried to rectify his lapse in judgment by discharging the recruit, although after he had already been given his recruitment bounty and service clothes.[100] On August 14, 1780, at Fort Pitt, Captain Beall was tried by court-martial, found guilty of "discharging a Soldier after having been duly inlisted [sic] and receiving his regimental cloathing [sic] through private and interested views thereby defrauding the United States," and on October 13, was dismissed from the service.[101] Capt. Adamson Tannehill succeeded Beall as commander of the regiment for the remaining few months of the unit's existence.[76]

Disbanding

On November 1, 1780, Washington issued orders approved by Congress that specified plans for the comprehensive reorganization of the Continental Army effective January 1, 1781.[102] All Additional and Extra Continental regiments, such as the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment, that had not been annexed to a state line organization were disbanded by that date. The much-diminished unit comprised only 2 officers and 50 enlisted men in late December 1780.[76] The officers received discharges on January 1, 1781,[103] and the enlisted men of the unit were transferred to the Maryland Line.[104] Relocation of the men from their remote post at Fort Pitt to their new assignments, however, was not completed until November 1781, at least in part because their officers were not present to supervise the process.[105]

The lineage of the regiment's Virginia elements is carried on by the 201st Field Artillery Regiment (United States).[106]

Notes

- 1 2 Maryland Historical Society (1927), pp. 275, 278.

- ↑ Washington to Congress (July 4, 1776).

- ↑ Ford, v. 5, pp. 452, 486.

- ↑ Ford, v. 2, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Balch, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Wright, p. 319.

- ↑ Ford, v. 5, p. 452.

- ↑ Wright, pp. 98–99, 319.

- ↑ Heitman, p. 459.

- 1 2 Ford, v. 5, p. 486.

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 130–133.

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Ford, v. 5, pp. 762–763.

- ↑ Linn and Egle, series 2, v. 10, p. 106.

- ↑ Showman et al., v. 1, pp. 328–329.

- 1 2 3 4 Rawlings to Washington (August 1778).

- ↑ The Historical Society of Pennsylvania (1901), pp. 259–262.

- ↑ Fischer, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Dandridge, pp. 11–19.

- ↑ Washington to Congress (September 28, 1776).

- 1 2 With Stephenson's death, Washington recommended to Congress in late September 1776 that the colonel's position be held vacant to allow Capt. Daniel Morgan to replace Stephenson once he was released from British captivity (Washington to Congress, September 28, 1776). Morgan had been taken prisoner in December 1775 at the Battle of Quebec City during the Canadian campaign (Higginbotham, pp. 27–54). Like Stephenson, he was one of the original captains of the four independent Continental rifle companies that formed in neighboring frontier counties of Maryland and Virginia in mid-1775 (Graham, pp. 53–54; Hentz, pp. 129, 132); three of these companies composed the core element from which the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment was formed and its field officers were drawn. Washington believed Morgan to be Stephenson's appropriate successor because he was senior in rank to the regiment's two remaining field officers (Rawlings, Williams) when they entered the service. The Virginia state government, however, endorsed Morgan as the colonel of the newly formed 11th Virginia Regiment when, by Congressional mandate, the state was required to raise several new regiments in late 1776 (Wright, p. 108). Anticipating Morgan's impending exchange, Congress issued his commission as colonel of the new Virginia line infantry unit on November 12, 1776 (Graham, p. 118). Morgan took command of the regiment upon his exchange in January 1777 (Higginbotham, p. 56). The position of colonel in the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment was never refilled.

- 1 2 Smith's Co. muster roll (May 16, 1777).

- 1 2 3 4 Long's Co. muster roll (May 16, 1777).

- ↑ Force, pp. 663–664.

- ↑ Rider and Dych war-pension testimonies.

- 1 2 Smith's Co. pay roll (May 1, 1777).

- ↑ Force, pp. 1035–1036.

- ↑ Washington to Congress (December 24, 1776).

- ↑ Lingan and Davenport war-pension testimonies.

- ↑ Harris and Smith war-pension testimonies.

- ↑ Force, pp. 1401–1402.

- ↑ Fischer, p. 408.

- ↑ Fischer, pp. 346–362.

- ↑ In late January or early February 1777, the effective force of the two composite companies was temporarily diminished when those members of the units who had not already had smallpox marched to Whippany, just northeast of Morristown, where they underwent inoculation (Maryland Historical Society [1910], p. 132), a process that typically lasted four to six weeks. Smallpox had seriously affected the readiness of the Continental Army earlier in the war. Therefore, starting in early 1777, Washington required smallpox inoculation of all troops who had not already suffered from, and thus had no immunity to, the virus (Washington to Shippen, January 6, 1777).

- ↑ Most of the Pennsylvanian riflemen were from the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, originally called the Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment (Hentz, p. 136). Among the other Virginian riflemen present were members of the three-company rifle elements from each of the few Virginia line infantry regiments that were with the Main Army during most of the winter and spring of 1777 (Wright, pp. 68–70, 108, 283, 285–287).

- ↑ Hendricks to Washington (April 12, 1777). James Hendricks was at this time the lieutenant colonel of the 6th Virginia Regiment (Heitman, p. 285).

- ↑ Hentz, p. 136.

- ↑ Russell and Gott, p. 171.

- ↑ Morgan built his new 11th Virginia Regiment around a cadre of officers and enlisted men from his 1775 independent Virginia rifle company (Wright, p. 108), which served alongside the other three independent Maryland and Virginia rifle companies at the Siege of Boston before it left to join Arnold's expedition to Quebec (Hentz, p. 129). He and his company were captured at the Battle of Quebec City in December 1775 and not exchanged until late 1776 and early 1777. As Washington was aware, Morgan's 1775 veterans and many of the new recruits that composed the 11th Virginia Regiment hailed from the same frontier area of northwest Virginia as many members of Long's composite company (Wright, pp. 289, 319). Moreover, a number of men in Smith's composite company came from the adjacent frontier region of western Maryland.

- ↑ Hentz, p. 135.

- ↑ Washington to Morgan (June 13, 1777).

- ↑ Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay roll (July 1777).

- ↑ Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay rolls (July 1777 – May 1778).

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Heitman, p. 356.

- 1 2 Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay rolls (April – September 1779).

- 1 2 Maryland Historical Society (1900), v. 18, pp. 350–351.

- ↑ Washington General Orders (November 7, 1779).

- ↑ Higginbotham, pp. 55–77.

- ↑ Wright, p. 289.

- 1 2 3 Wright, p. 290.

- ↑ Davenport, Callender, and Debruler war-pension testimonies.

- ↑ Wright, p. 279.

- ↑ Smith's Co. muster rolls (1778).

- ↑ Fritts war-pension testimony.

- ↑ Long's Co. muster rolls (July 1777 – May 1778).

- ↑ Heitman, p. 499.

- 1 2 Rawlings to Congress (November 28, 1785).

- ↑ Browne (1897), v. 16, pp. 555–556.

- ↑ Maryland Historical Society (1900), v. 18, p. 616.

- ↑ Heitman, p. 596.

- 1 2 Steiner (1924), v. 43, p. 424.

- ↑ Browne (1901), v. 21, pp. 147–148.

- 1 2 Browne (1901), v. 21, p. 148.

- ↑ Browne (1897), v. 16, pp. 448–450.

- ↑ Ford, v. 12, p. 993.

- ↑ Wright, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Washington to Congress (January 21, 1779).

- ↑ Ford, v. 13, p. 104.

- ↑ Washington to Rawlings (March 21, 1779).

- ↑ Williams, pp. 47–48, 148–289.

- ↑ Washington General Orders (February 16, 1779). The officer in Rawlings' regiment to whom the detached members were to be delivered ("Lieutenant Tauneyhill [sic]") is 1st Lt. Adamson Tannehill, an original member of the unit.

- ↑ Callender and Debruler war-pension testimonies.

- ↑ McIlwaine, v. 1, pp. 320–324.

- ↑ Kellogg (1917), p. 454.

- 1 2 3 Returns of the Maryland Corps (December 25, 1780).

- ↑ Browne (1901), v. 21, pp. 339–340.

- ↑ Tannehill to Roberts (April 24, 1818). Adamson Tannehill signed his one-page letter supporting the war-service pension claim of John Callender, his former subordinate at Fort Pitt and fellow Pittsburgh resident: "Witness my hand, A. Tannehill, late Capt. in Rawlings Regt. — commonly called the Maryd. Rifle Corps."

- ↑ Kellogg (1917), p. 400.

- 1 2 Hoenstine, p. 64.

- ↑ Beall to Washington (May 7, 1779).

- ↑ Tannehill to Smallwood (December 25, 1780).

- ↑ Hentz, p. 139.

- 1 2 Brodhead to Washington (May 29, 1779).

- ↑ Johnson to Washington (April 23, 1779).

- ↑ Ford, v. 11, pp. 538–539.

- 1 2 Steuart, p. 122.

- ↑ Browne (1901), v. 21, p. 546.

- ↑ Hunt, v. 17, p. 807.

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 130–141.

- ↑ Brodhead to Washington—Return of troops in the Western Department (April 17, 1779).

- ↑ Wright, pp. 265, 291.

- ↑ Pleasants, v. 47, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Dowden war-pension testimony.

- ↑ Hazard, series 1, v. 12, pp. 155–158.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 192–202, 238–296.

- ↑ Kellogg (1916), p. 364.

- ↑ Kellogg (1917), p. 309.

- ↑ Hazard, series 1, v. 12, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Steiner (1927), v. 45, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Washington General Orders (October 13, 1780).

- ↑ Washington General Orders (November 1, 1780).

- ↑ Maryland Historical Society (1900), v. 18, p. 365.

- ↑ Washington to Brodhead (January 10, 1781).

- ↑ Pleasants, v. 47, p. 547.

- ↑ Lineage and honors certificate, 201st Field Artillery Regiment (March 12, 2003).

References

Primary references (books)

- Balch, Thomas, ed. (1857). Papers relating chiefly to the Maryland Line during the Revolution. Philadelphia: T. K. and P. G. Collins, pp. 4–5 (Proceedings of the Frederick County Committee of Observation, June 21, 1775).

- Browne, William H., ed. (1897). Archives of Maryland: journal and correspondence of the Council of Safety, January 1 – March 20, 1777; Journal and correspondence of the State Council, March 20, 1777 – March 28, 1778. Baltimore: The Friedenwald Co., v. 16, pp. 448–450 (Washington to Johnson, December 29, 1777), 555–556 (Council of Maryland to Gates, March 27, 1778).

- Browne, William H., ed. (1901). Archives of Maryland: journal and correspondence of the Council of Maryland, April 1, 1778 – October 26, 1779. Baltimore: The Lord Baltimore Press, v. 21, pp. 147–148 (Council of Maryland correspondence, June 24, 1778), 148 (Council of Maryland to Hughes, June 24, 1778), 339–340 (Washington to Johnson, April 8, 1779), 546 (Council of Maryland to Wiley, October 4, 1779).

- Dandridge, Danske (1911). American prisoners of the Revolution. Charlottesville: The Michie Co., pp. 11–19 (undated letter from Maj. Henry Bedinger to son of Gen. Samuel Finley). ISBN 1-4069-3807-6.

- Force, Peter (1853). American archives. Washington: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, Fifth Series, v. 3, pp. 663–664 ("Return of the Forces encamped on the Jersey Shore, commanded by Major-General Greene, November 13, 1776"), 1035–1036 ("General Return of the Army. Trenton, December 1st, 1776"), 1401–1402 ("Return of the Forces in the service of the States of America, encamped and in quarters on the banks of Delaware, in the State of Pennsylvania ... December 22d, 1776").

- Ford, Worthington C., ed. (1905, 1906, 1908, 1909). Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, v. 2, pp. 89–90, v. 5, pp. 452, 486, 762–763; v. 11, pp. 538–539; v. 12, p. 993; v. 13, p. 104.

- Graham, James (1859). The life of General Daniel Morgan of the Virginia Line of the army of the United States. New York: Derby & Jackson, pp. 53–54 (Proceedings of the Frederick County, Virginia, Committee, June 22, 1775; and Morgan's commission, June 22, 1775), 118 (Morgan's commission, November 12, 1776). ISBN 1-880484-06-4.

- Hazard, Samuel, ed. (1856). Pennsylvania Archives. Philadelphia: Joseph Severns & Co., series 1, v. 12, pp. 155–158 (Brodhead to Washington, September 16, 1779), 194–195 (Finley to Taylor, November 28, 1779).

- Hunt, Gaillard, ed. (1910). Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, v. 17, p. 807.

- Kellogg, Louise P. (1916). Frontier advance on the upper Ohio, 1778–1779. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, p. 364 (Brodhead's orders, June 14, 1779). ISBN 0-7884-0048-7.

- Kellogg, Louise P. (1917). Frontier retreat on the upper Ohio, 1779–1781. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, pp. 309 (Brodhead to Clark, December 16, 1780), 400 (Brodhead to Huntington, May 30, 1781), 454 (Order for a court of inquiry, Fort Pitt, September 3, 1780). ISBN 0-8063-5191-8.

- Linn, John B., and Egle, William H., eds. (1880). Pennsylvania Archives. Harrisburg: Lane S. Hart, series 2, v. 10, p. 106 ("Return of the Troops on York Island in the Service of the United States, Commanded by Col. Magaw, November 7, 1776"). The digital link is to a later edition of this citation and shows a different page number.

- McIlwaine, Henry R., ed. (1931). Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia. Richmond: The Virginia State Library, v. 1, pp. 320–324 (Council meeting, February 3, 1777).

- Maryland Historical Society (1900). Archives of Maryland: muster rolls and other records of service of Maryland troops in the American Revolution (1775–1783). Baltimore: The Lord Baltimore Press, v. 18, pp. 350–351 ("Muster Roll of the Maryland Corps in the Service of the U. States, Commanded by Captain Thomas Beall for the Months of Jan., Feb., March, April, May, June, July, Aug., Sept. and Oct. 1780"), 365 ("Officers in the Maryland part of the Rifle Regiment Supernumerary Jany., 1st, 1781"), 616 ("Return of Maryland Officers exchanged from the 24th March, 1777").

- Pleasants, J. Hall, ed. (1930). Archives of Maryland: journal and correspondence of the State Council of Maryland, 1781. Baltimore: The Lord Baltimore Press, v. 47, pp. 129–130 (Swearingen to Lee, March 16, 1781), 547 (Gibson to Lee, November 12, 1781).

- Showman, Richard K., Cobb, Margaret, and McCarthy, Robert E., eds. (1976). The papers of General Nathanael Greene. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, v. 1, pp. 328–329 (Greene to Washington, October 31, 1776). ISBN 0-8078-1285-4.

- Steiner, Bernard C., ed. (1924). Archives of Maryland: journal and correspondence of the State Council of Maryland, 1779–1780. Baltimore: The Lord Baltimore Press, v. 43, p. 424 (Beall to Council of Maryland, February 10, 1780).

- Steiner, Bernard C., ed. (1927). Archives of Maryland: journal and correspondence of the State Council of Maryland, 1780–1781. Baltimore: The Lord Baltimore Press, v. 45, pp. 69–70 (Beall to Lee and Council of Maryland, August 30, 1780).

Primary references (periodicals)

- The Historical Society of Pennsylvania (1901). "Letter of Lambert Cadwalader to Timothy Pickering on the capture of Fort Washington [May 1822]." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 25, 259–262. ISSN 0031-4587.

- Hoenstine, Floyd G., ed. (1976). "Expenditures and receipts at Fort Pitt, PA., October 27, 1779 to December 31, 1781, as copied from the ledger used by John Boreman, [Deputy] Paymaster General [of the Western Department], Continental Army." Your Family Tree: Pennsylvania Genealogy and History West of the Susquehanna 22(3), 62–65. OCLC 41385183.

- Maryland Historical Society (1910). "Alex. Lawson Smith to Lieut. Michael Gilbert [February 17, 1777]." Maryland Historical Magazine 5, 131–134. ISSN 0025-4258.

- Maryland Historical Society (1927). "A muster roll of Captain Thomas Price's Company of Rifle-Men in the service of the United Colonies." Maryland Historical Magazine 22, 275–283. ISSN 0025-4258.

Primary references (archive documents)

- Beall to Washington (May 7, 1779): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 34, frames 375-376.

- Brodhead to Washington—Return of troops in the Western Department (April 17, 1779): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Brodhead to Washington (May 29, 1779): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Callender and Debruler war-pension testimonies: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804: roll 452, frames 006–015, claim no. S 40792 (Pvt. John Callender); roll 782, frames 729–744, claim no. S 35890 (Pvt. John Debruler).

- Davenport, Callender, and Debruler war-pension testimonies: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804: roll 744, frames 038–059, claim no. S 35874 (Pvt. Adrian Davenport); roll 452, frames 006–015, claim no. S 40792 (Pvt. John Callender); roll 782, frames 729–744, claim no. S 35890 (Pvt. John Debruler).

- Dowden war-pension testimony: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804, roll 844, frames 145–161, claim no. S 30996 (Pvt. James Dowden).

- Fritts war-pension testimony: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804, roll 1029, frames 580–596, claim no. S 42732 (Pvt. Valentine Fritts).

- Harris and Smith war-pension testimonies: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804: roll 1199, frames 493–499, claim no. S 31726 (Pvt. James Harris, Long's Co.); roll 2216, frames 514–531, claim no. W 19052 (Pvt. Jacob Smith, Long's Co.).

- Hendricks to Washington (April 12, 1777): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Johnson to Washington (April 23, 1779): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Lingan and Davenport war-pension testimonies: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804: roll 1567, frames 879–891, claim no. S 34962 (Lt. Thomas Lingan, Smith's Co.); roll 744, frames 038–059, claim no. S 35874 (Pvt. Adrian Davenport, Smith's Co.).

- Lineage and honors certificate, 201st Field Artillery Regiment (March 12, 2003): United States Army Center of Military History, Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, D.C.

- Long's Co. muster roll (May 16, 1777): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 109, frames 492–494 ("A Muster Roll of Capt. Gabriel Long's Company of the Eleventh Virginia Regiment of Foot Commanded by Col. Daniel Morgan ... May 16th 1777—Together with part of Capts. Shepherd, West's & Brady's Compys").

- Long's Co. muster rolls (July 1777 – May 1778): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 109, frames 495–527.

- Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay roll (July 1777): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 133, frames 414–415 ("Pay Roll of Capt. Gabl. Long's Detach'd Comy. of Rifle men Commdd. by Colo. Danl. Morgan for the month of July 1777").

- Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay rolls (July 1777 – May 1778): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 133, frames 414–450.

- Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay rolls (April – September 1779): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, Microcopy M246, roll 133, frames 433–448.

- Rawlings to Congress (November 28, 1785): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 360, microcopy M247, roll 51, item 41, v. 8, pp. 361–363.

- Rawlings to Washington (August 1778): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 360, microcopy M247, roll 51, item 41, v. 8, p. 365.

- Returns of the Maryland Corps (December 25, 1780): Maryland State Archives, Maryland State Papers (Series A), Box 21, Items 119A and 119B, MSA No. S 1004-27 ("A Return of the Commissioned Officers of the Maryland Corps [Late Rawlings's] Specifying their Names, Rank, Claims to Promotion &c." and "Return of the Non-Commission'd officers & Rank and File of the Maryland Corps [formerly Commanded by Lieut. Colo. Moses Rawlings] of Foot in the Army of the United States, under the Command of His Excellency Genl. Washington, Specifying the expiration of Inlistments, Monthly from the 10th. of October 1780 to July next inclusively, together with the number engaged to Serve during the War").

- Rider and Dych war-pension testimonies: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804: roll 2045, frames 001-010, claim no. S 40341 (Pvt. Adam Rider); roll 879, frames 446–452, claim no. S 42689 (Pvt. Peter Dych).

- Smith's Co. pay roll (May 1, 1777): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 126, frames 190–200 (at end of roll 126) ("Pay Roll of Capt. Alex. Lawson Smith's Comy. with part of Capts. Griffith's, Davis' & Beall's Comys. of Lieut. Colo. Moses Rawlings Batn. Riflemen, now under Command of Colo. Danl. Morgan of the 11th Virginia Regiment ... 1st Day of May 1777").

- Smith's Co. muster roll (May 16, 1777): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 126, frames 175–176 (at end of roll 126) ("A Muster Roll of Capt. Alexr. Lawson Smith's Company Including part of other Company's belonging to the same Regiment of Lieut. Colo. Rawling's Batn. of Foot now under Commnd. [sic] of Colo. Daniel Morgan of 11th Virga. Regmt.").

- Smith's Co. muster rolls (1778): Maryland Historical Society, Revolutionary War Collection, MS 1814.

- Tannehill to Roberts (April 24, 1818), in Callender war-pension testimony: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 15, microcopy M804, roll 452, frame 13, claim no. S 40792 (Pvt. John Callender).

- Tannehill to Smallwood (December 25, 1780): Maryland State Archives, Maryland State Papers (Series A), Box 21, Item 120, MSA No. S 1004-27.

- Washington to Brodhead (January 10, 1781): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Washington to Congress (July 4, 1776): U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 360, microcopy M247, roll 166, item 152, v. 2, pp. 152–157.

- Washington to Congress (September 28, 1776): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries A, Letterbook 2.

- Washington to Congress (December 24, 1776): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries A, Letterbook 2.

- Washington to Congress (January 21, 1779): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Washington General Orders (February 16, 1779): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries G, Letterbook 4.

- Washington General Orders (November 7, 1779): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries G, Letterbook 4.

- Washington General Orders (October 13, 1780): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries G, Letterbook 5.

- Washington General Orders (November 1, 1780): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries G, Letterbook 5.

- Washington to Morgan (June 13, 1777): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Washington to Rawlings (March 21, 1779): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4.

- Washington to Shippen (January 6, 1777): Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries B, Letterbook 2.

Secondary references

- Fischer, David H. (2004). Washington's crossing. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517034-2.

- Heitman, Francis B. (1914). Historical register of officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783. Washington, D.C.: The Rare Book Shop Publishing Co., pp. 285, 356, 459, 499, 596. ISBN 0-548-21649-5.

- Hentz, Tucker F. (2006). "Unit history of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (1776–1781): Insights from the service record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill." Military Collector & Historian 58(3), 129–144. ISSN 0026-3966.

- Higginbotham, Don (1961). Daniel Morgan, revolutionary rifleman. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1386-9.

- Russell, T. Triplett, and Gott, John K. (1977). Fauquier County in the Revolution. Warrenton: Warrenton Printing & Publishing Company. ISBN 1-888265-60-4.

- Steuart, Rieman (1969). A history of the Maryland Line in the Revolutionary War, 1775–1783. Towson: Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland.

- Williams, Glenn F. (2005). Year of the hangman: George Washington's campaign against the Iroquois. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, LLC. ISBN 1-59416-013-9.

- Wright, Robert K., Jr. (1983). The Continental Army. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History Publication 60-4-1, U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-16-001931-1.

Further reading

- Hentz, Tucker F. (2007). Unit history of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (1776-1781): Insights from the service record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill. Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, Library General Collection, call number E259 .H52 2007, 46 p. (Expanded archive manuscript from which Hentz [2006] is derived.)