Mary Louise Booth

| Mary Louise Booth | |

|---|---|

Mary Louise Booth | |

| Born |

April 19, 1831 Millville, the present-day Yaphank, New York, United States |

| Died | March 5, 1889 (aged 57) |

| Occupation | Editor, translator, writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

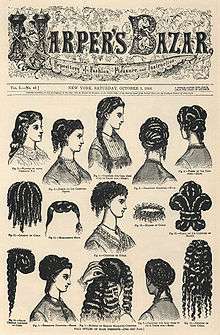

| Notable works | editor-in-chief, Harper's Bazaar |

| Years active | 1845–1889 (her death) |

| Partner | Mrs. Anno W. Wright |

Mary Louise Booth (April 19, 1831 – March 5, 1889) was an American editor, translator and writer. She was the first editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar.

At the age of 18, she left the family home for New York City and learned the trade of a vestmaker. She devoted her evenings to study and to writing. She contributed tales and sketches to various newspapers and magazines, but was not paid for them. She began to do reporting and book-reviewing for educational and literary journals, still without any pay in money, but happy at being occasionally paid in books. She said: "It is my college, and I must learn my business before I can demand pay." In 1856, she compiled a marbleworker's manual, such as had been issued in France, but although it was published, she again was given only books for compensation. As time went on, she received more and more literary work to do, and though still obliged at times to walk four miles for lack of horse-car fare, she made steady progress. She widened her circle of those friends who were beginning to appreciate her abilities. In 1859, she agreed to write a history of New York within a year, and succeeded in doing so; but even then, she was unable to support herself wholly, although she had given up vestmaking and was writing 12 hours a day. When she was 30 years old, she accepted the position of amanuensis to Dr. J. Marion Sims, and this was the first work of the kind for which she received steady payment. She was now able to do without her father's assistance, and live on her own resources in New York, though very plainly.[1]

In 1861, at the beginning of American Civil War, she procured the advance sheets, in French, of Agénor de Gasparin's "Uprising of a Great People," and hurried to Scribner's with it to ask if they would publish it if she would translate it. She was told that it would be valuable if it could be issued immediately, but that the war would not last more than a month, and then it would not be so interesting.[1] Booth took the book home with her. By working 20 hours a day, she translated the whole book in less than a week, and it was published in a fortnight. The book created a great sensation among Northerners, and both Charles Sumner and President Lincoln wrote her letters of thanks. But though Sumner wrote her that what she had done was "worth a whole phalanx in the cause of human freedom," again she received but little pecuniary compensation. While the war lasted, however, she translated many French books calculated to rouse patriotic feeling, and was, at one time, summoned to Washington to write for the men whose work for their country she considered it a privilege to help, receiving only her board at a hotel. She was able at this time to procure for her father the position of clerk in the New York Custom House, and so relieve him from the very wearing night work he had been doing.[2]

At the end of the American Civil War, Booth had proved so well her fitness for the position that the Messrs. Harper offered her the editorship of Harper's Bazaar – headquartered in New York City – from its beginning in 1867 until her death. She was at first diffident as to her powers, but finally accepted the responsibility, and it was principally due to her that the magazine became so popular. While keeping its character of a home paper, it steadily increased in influence and in circulation, and Booth's success was achieved with that of the paper she edited. She is said to have received a larger salary than any woman in America at the time. She died, after a short illness, on March 5th, 1889. [2]

Early years and education

Mary Louise Booth was born in Millville, the present-day Yaphank, New York, to William Chatfield Booth and Nancy Monswell. She was descended on her father's side from John Booth, who came to America about 1649, while her mother was the granddaughter of a refugee of the French Revolution (1789–1799).

She was a precocious child, — so much so that, on being asked, she once confessed she had no more recollection of learning to read either French or English than of learning to talk. As soon as she could walk, her mother said, she was following her about, book in hand, begging to be taught to read stories for herself. She read them soon to so much purpose that before she was five years old, she had finished the Bible, being rewarded by a polyglot Testament for the feat, and had also read Plutarch, which at every subsequent reading gave her an equal pleasure, and at seven, had mastered Racine in the original, upon which she began the study of Latin with her father.[3]

From that time she was an indefatigable reader, troubling her parents only by her devotion to books rather than to the play natural to her age. Her father had a considerable library, the contents of every book in which she made her own, always preferring history, — before she had finished her 10th year being acquainted with Hume, Gibbon, Alison, and kindred writers. At this point, she was sent away to school. Her father and mother, seeing the intellect for which they were responsible, took all possible pains with her education, and fortunately her physical strength was sufficient to carry her through an uninterrupted course in different academies and a series of lessons with masters at home. She cared more for languages and natural sciences, in which she was very proficient, than for most other studies, and took no especial pleasure in mathematics.[4] Booth's superior education was not given her at school, where she learned less than she did by herself, for she showed very young that disdain of obstacles and that taste for literature which were two strong points in her character. She was only a tiny child when she taught herself French. A stray French primer fell into her hands, and she became interested in spelling out the French words and comparing them with the English ones, and continued to study in this way. Later she acquired German in the same manner, and being self-taught, and not hearing either language, she never learned to speak them, but made herself so proficient in them in after years that she could translate almost any book from either German or French at sight, reading them aloud in English.[5]

When she was about 13 years of age, her father, William Chatfield Booth, moved his family from Yaphank, in which she was born, to Brooklyn, New York,[5] and there Mr. Booth organized the first public school that was established in that city. Mr. Booth was a man well qualified both by education and by native character for the guidance of such an intelligence as that developed by his daughter. Deeply interested in scholarly matters, a man of great directness of purpose and of fearless integrity, he and his daughter were in perfect sympathy, and he watched her growth with tender solicitude, and in subsequent years cherished with pride every word of her writing. But he could never quite bring himself to believe, even after she had won a handsome independence by her exertions, that she was really altogether capable of her own support, and always insisted upon making her the most generous gifts. As the President of the United States said of him, "A kinder and more honorable gentleman it would be hard to find."[4] Another daughter and two sons comprised the remainder of his family, the younger of the sons, Colonel Charles A. Booth, saw 20 years' service in the army.[6]

She was of French descent on her mother's side,[5] and the mother was still living, at the age of 80.[6] Booth's father, William Chatfield Booth, was descended from one of our earliest settlers, John Booth, who came to the U.S. in 1649, a kinsman of the Sir George Booth, afterwards Baron Delamere and Earl of Warrington, who, was the faithful friend and companion of Charles II in his exile. In 1652, Ensign John Booth purchased Shelter Island from the Native Americans, for 300 feet (91 m) of calico.[5] For at least 200 years, the family stayed close by.[6] Booth's father, for some years, provided night-watchmen for several large business houses in New York, and he was obliged to personally oversee them from 9:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M.[5]

As she grew older her determination to make literature her profession became very strong, and no discouragements ever altered her purpose. As she was the oldest of four children, her father did not feel that it would be fair to the others to give her more than her just proportion of aid, since the others might also, in time, require assistance. Consequently, when at eighteen years old Miss Booth decided that it was necessary for her work that she should be in New York, she could not depend entirely upon her father. While not disregarding any expressed wish of her parents, she made her own decision as to the chief aim of her life.[5] She was now obliged to leave them, and in some way to earn the difference between the sum her father could allow her and her expenses, and also to find time and opportunity for that other work to which she meant to make everything subordinate.[1]

Early career

A friend who was a vest-maker offered to teach her the trade, and to help her to get work, and this enabled her to carry out her plan of going to New York. She took a small room in the city, and went home only for Sundays, as the communication between Williamsburg and New York was very slow in those days, and the journey could not be made in leas than three hours. Two rooms were always kept ready for her in her parents' house, and those Sundays at home must have been a great rest and pleasure to her, though her family felt so little sympathy in her literary work that she rarely mentioned it at home.[1]

In 1845 and 1846, Booth taught in her father's school in Williamsburg, New York, but gave up that pursuit on account of her health, and devoted herself to literature. Booth wrote tales and sketches for newspapers and magazines. She translated from the French The Marble-Worker's Manual (New York, 1856) and The Clock and Watch Maker's Manual. She translated Joseph Méry's André Chénier and Edmond François Valentin About's The King of the Mountains for Emerson's Magazine, which also published her own original articles. Booth next translated Victor Cousin's Secret History of the French Court: or, Life and Times of Madame de Chevreuse (1859). That same year, the first edition of her History of the City of New York appeared, which was the result of great research. Next she assisted Orlando Williams Wight in making a series of translations of the French classics, and she also translated Edmund About's Germaine (Boston, 1860).[6]

Booth was still scarcely more than a young girl when a friend suggested to her that no complete history of the city of New York had ever been written, and that it might be well to prepare such a one for the use of schools. Although without ambition to attempt the impossible, yet never daunted by the possible, she at once busied herself in the undertaking, and, after some years spent in preparation, finished one that became, on the request of a publisher, the basis of a more important work upon the same subject, her material having far outgrown the limits proposed, and her experience having taught her the best way of using it. She knew that it was no petty work, as many of the most stirring events of colonial and national history were connected with its story.[7] During the course of her historical work, Booth had full access to libraries and archives. Washington Irving sent her a letter of cordial encouragement, and D. T. Valentine, Henry B. Dawson, W. J. Davis, E. B. O'Callaghan, and numerous others showered her with documents and every assistance. "My Dear Miss Booth," writes Benson G. Lossing, "the citizens of New York owe you a debt of gratitude for this popular story of the life of the great metropolis, containing so many important facts in its history, and included in one volume accessible to all. I congratulate you on the completeness of the task and the admirable manner in which it has been performed." The history appeared in one large volume, and met at once with a generous welcome, whose pecuniary results were very considerable. So satisfactory, indeed, was its reception, that the publisher proposed to her to go abroad and write popular histories of the great European capitals, London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna. It was a bright vision for the young writer, but the approach of war and other fortuitous circumstances prevented its becoming a reality.[8]

American Civil War years

Shortly after the publication of the first edition of this work, the civil war broke out. Booth had always been a warm anti-slavery partisan and a sympathizer with movements for what she considered true progress, although directed by that calm judgment which never lets the heart run away with the head. But here heart and head were in accord, the country was aflame with fervor to prevent the destruction of the noblest government ever given to man; and all hoped that a certain result of the struggle would be that universal freedom without which the freedom already vaunted was a lie.[9]

Booth was, of course, enlisted on the side of the Union, and longing to do something to help the cause in which she so ardently believed. She did not feel herself qualified to act as a nurse in the military hospitals, not only having that inherent antipathy to the sight of sickness and suffering common to many poetic natures, although willing to endure all that such sight and association could bring, but being, through her life among books, too inexperienced in such work to venture assuming its tasks with their consequent risk of life. Still something she must do. That she had sent her brother to the front, scarcely more than a boy, as he was, seemed not half enough ; and, when, while burning with eagerness she received an advance copy of Count Agenor de Gasparin's "Uprising of a Great People," she at once saw her opportunity in bringing heartening words to those in the terrible struggle.

She took the work, without loss of time, to Mr. Scribner, proposing he should publish it. He demurred a little, saying he would gladly do so if the translation were ready, but that the war would be over before the book was out, Mr. Seward having authoritatively limited its duration to a small number not of weeks but of days. Mr. Scribner finally said, perhaps but half believing in the possibility, that if it could be ready in a week he would publish it. "It shall be done," was her reply, and she went home and went to work, working twenty hours of every twenty-four, receiving the proofsheets at night and returning them with fresh copy in the morning. The week lacked several hours of its completion when the work was finished, and in a fortnight the book was out, and its message rang from Maine to California.

Nothing published during the war made half the sensation that did this prophetic volume, whose predictions were so wonderfully accurate that very few of them were found to have proved false at the end of the dark contest, dark not only because beginning to be so doubtful, and laden with sorrow, and suffering, and loss, but because, although the North shone in the light of a glorious resolve, and the South contended for principle, the struggle was still one between brothers. The newspapers of the day were full of reviews and notices, eulogistic and otherwise, according to the party represented. The book revived courage and rekindled hope. "It is worth a whole phalanx in the cause of human freedom," wrote Charles Sumner; and Abraham Lincoln paused in the midst of his mighty work to send her a letter of thanks and lofty cheer.[10]

The publication of the book was the means of putting Booth at once into communication with the author and his wife, who begged her to visit them in Switzerland; and it subsequently brought about a correspondence with most of those European sympathizers with the North who handled a pen, such as Augustin Cochin, Edouard Laboulaye, Henri Martin, Edmond de Pressense, Conte du Montalembert, Monseigneur Dupanloup, and others, — men of all shades of religious and political belief at home, but united in the hatred of slavery, and in sympathy for the cause in whose success its extinction was involved.[11] These gentlemen vied with each other in sending her advance-sheets of their boots, and numerous articles, letters, and pamphlets to meet the question of the day, which she swiftly translated, publishing them without money and without price, in the daily journals, and through the avenues afforded by the Union League Club. In return, she kept these noble Frenchmen accurately informed of the progress of events, and sent them such publications as could be of service.[11]

A second edition of the history was published in 1867, and a third edition, revised and brought down to date, appeared in 1880. A large paper edition of the work was taken by well-known book-collectors, extended and illustrated by them with supplementary prints, portraits, and autographs on the interleaved pages.[8] One copy, enlarged to folio and extended to nine volumes by several thousand maps, letters, and other illustrations, is owned in the city of Naw York, and is an unequalled treasure-house of interest. Booth owned a copy that was presented to her by an eminent bibliopolist, enriched by more than two thousand of those illustrations on inserted leaves.[12]

Translator

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Booth translated the works of eminent French writers in favor of the cause of the Union. In rapid succession appeared translations of: Agénor Gasparin's Uprising of a Great People and America before Europe (New York, 1861), Édouard René de Laboulaye's Paris in America (New York, 1865), and Augustin Cochin's Results of Emancipation and Results of Slavery (Boston, 1862). For this work she received praise and encouragement from U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, U.S. Senator Charles Sumner, and other statesmen. During the entire war she maintained a correspondence with Cochin, Gasparin, Laboulaye, Henri Martin, Charles Forbes René de Montalembert, and other European sympathizers with the Union. At that time, she also translated the Countess de Gasparin's Vesper, Camille, and Human Sorrows, and Count Gasparin's Happiness. Documents forwarded to her by French friends of the Union were translated and published in pamphlets, issued by the Union League Club, or printed in the New York journals. Booth translated Henri Martin's History of France. The two volumes treating of The Age of Louis XIV were issued in 1864, and two others, the last of the seventeen volumes of the original work, in 1866 under the title of The Decline of the French Monarchy. It was intended to follow these with the other volumes from the beginning, but, although she translated two others, the enterprise was abandoned for lack of success, and no more were printed. Her translation of Martin's abridgment of his History of France appeared in 1880. She also translated Laboulaye's Fairy Book, Jean Macé's Fairy Tales and Blaise Pascal's Lettres provinciales (Provincial Letters). The "Uprising of a Great People", was followed rapidly by Gasparin's "America Before Europe," by Laboulaye's "Paris in America," and two volumes by Augustin Cochin, " Results of Emancipation" and "Results of Slavery." Cochin's work attracted even more attention than Gasparin's had done. She received hundreds of appreciative letters from the leading Republican statesman — Henry Winter Davis, Senator Doolittle, Galusha A. Grow, Dr. Lieber, Dr. Bell, the president of the Sanitary Commission, and a host of others, among them George Sumner, Cassius M. Clay, and Attorney-General Speed, Charles Sumner writing her that Cochin's work had been of more value to the cause "than the Numidian cavalry to Hannibal."[11] In the meantime, she pursued her translations as before, adding to her list Laboulaye's "Fairy Tales," and Jean Mace's " Fairy Book," and several of the religious works of the Count and Countess do Gasparin, "Happiness" by the former, and "Camille," " Vesper," and " Human Sorrows " by the latter. Her translations in all number nearly forty volumes. She had thought of adding to this number, at the request of Mr. James T. Fields, an abridgment of George Sand's voluminous "Histoire de ma Vie". Circumstances, however, prevented the completion of the work.[13]

Harper's Bazaar

In the year 1867, Booth undertook another enterprise of an entirely opposite but no less important nature, in assuming the management of Harper's Bazaar, a weekly journal devoted to the pleasure and improvement of the domestic circle. She had long been in pleasant relations with the Messrs. Harper, the four brothers who founded the great house which bears their name, and who conducted its business to such splendid results; and when they resolved upon issuing a family newspaper of this description they immediately asked her to take its editorial control.[14]

Under her editorial management it proved the swiftest journalistic success on record, numbering its subscribers by the hundred thousand, and while other papers took a loss for granted in the beginning, putting itself upon a paying basis at the outset. While she had assistants in every department, among their names those of some most distinguished in our literature, she was herself the inspiration of the whole corps, and under the advice and suggestion of its proprietors she held it on an even course. There was scarcely a poet, or a story-writer, or novelist of any rank in America or England who is not a contributor to its pages, and its purity, its self-respect, its high standard, and its literary excellence, were unrivalled among periodical publications. The influence of such a paper within American homes was something hardly to be computed. It was always on the side of good and sweet things; it made the right seem the best and pleasantest; it taught while it has amused; it held the happiness, well-being, and virtue of women and the family as its first consideration, and it created a wholesome atmosphere wherever it was constantly read. Through its columns, its editor made her hand felt in countless families for nearly 16 years, and helped to shape the domestic ends of a generation to peace and righteousness.[15]

Personal life

Perhaps Booth could not have accomplished so much if she had been hampered, as many women are, by conditions demanding exertion in other than her chosen path, and without the comfort about her of a perfect home. She lived in the city of New York, in the neighborhood of Central Park, in a house which she owned, with her sister by adoption, Mrs. Anno W. Wright, between whom and herself there exists one of those lifelong and tender affections which are too intimate and delicate for public mention, but which are among the friendships of history, — a friendship that was begun in childhood and that cannot cease in death.[16]

Their house was one particularly adapted to entertaining, with its light and lovely parlors and connecting rooms. There were always guests, and in the salon, every Saturday night, there was an assemblage of authors of note, great singers, players, musicians, statesmen, travellers, publishers, journalists. Booth was blessed with steadfast friends. She forgot herself in serving others, and was happy in their happiness. She was described as sensitive, sympathetic and delicate.[16] Booth died, after a short illness, on March 5, 1889.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sharpless & Dewees 1890, p. 342.

- 1 2 3 Sharpless & Dewees 1890, p. 343.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 117.

- 1 2 Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sharpless & Dewees 1890, p. 341.

- 1 2 3 4 Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 119.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 120.

- 1 2 Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 121.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 126.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 128.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 123.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 129.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 130.

- ↑ Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 131.

- 1 2 Phelps, Stowe & Cooke 1884, p. 132.

Attribution

-

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Booth, Mary Louise". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Booth, Mary Louise". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. -

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Phelps, Elizabeth Stuart; Stowe, Harriet Beecher; Cooke, Rose Terry (1884). "Mary Louise Booth by Harriet Prescott Spofford". Our Famous Women: An Authorized Record of the Lives and Deeds of Distinguished American Women of Our Times ... A. D. Worthington & Company.

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Phelps, Elizabeth Stuart; Stowe, Harriet Beecher; Cooke, Rose Terry (1884). "Mary Louise Booth by Harriet Prescott Spofford". Our Famous Women: An Authorized Record of the Lives and Deeds of Distinguished American Women of Our Times ... A. D. Worthington & Company. -

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Sharpless, Isaac; Dewees, Watson W. (1890). The Student (Public domain ed.). Isaac Sharpless and Watson W. Dewees.

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Sharpless, Isaac; Dewees, Watson W. (1890). The Student (Public domain ed.). Isaac Sharpless and Watson W. Dewees.

Bibliography

- Stern, Madeleine B. (1975). "Booth, Mary Louise". In Edward T. James; Janet Wilson James. Notable American Women, 1607–1950 – A Biographical Dictionary. 1 (4th ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.

External links

- Works by Mary Louise Booth at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mary Louise Booth at Internet Archive

- Mary Louise Booth at Library of Congress Authorities, with 36 catalog records

.jpg)