Mary MacKillop

| St Mary of the Cross MacKillop | |

|---|---|

|

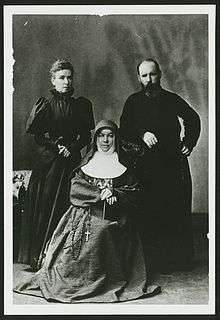

Mother Mary of the Cross (1869) | |

| Born |

15 January 1842 Newtown, New South Wales (now Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia) |

| Died |

8 August 1909 (aged 67) North Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 19 January 1995, Sydney, New South Wales, by Pope John Paul II |

| Canonized | 17 October 2010, Vatican City, by Pope Benedict XVI |

| Major shrine | Mary MacKillop Place, North Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Feast | 8 August |

| Patronage | Australia,[1] Brisbane,[2] Knights of the Southern Cross |

Mary Helen MacKillop RSJ (15 January 1842 – 8 August 1909), now formally known as St Mary of the Cross MacKillop, was an Australian nun who has been declared a saint by the Catholic Church. Of Scottish descent, she was born in Melbourne, but was best known for her activities in South Australia. Together with the Reverend Julian Tenison Woods, she founded the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart (the Josephites), a congregation of religious sisters that established a number of schools and welfare institutions throughout Australasia, with an emphasis on education for the rural poor.

With the process to have MacKillop declared a saint having begun in the 1920s, she was beatified in January 1995 by Pope John Paul II. Pope Benedict XVI prayed at her tomb during his visit to Sydney for World Youth Day 2008 and, in December 2009, approved the Catholic Church's recognition of a second miracle attributed to her intercession.[3] She was canonised on 17 October 2010, during a public ceremony in St Peter's Square at the Vatican.[4] She is the first and only Australian to be recognised by the Catholic Church as a saint.[5]

Early life and ministry

Mary Helen MacKillop was born on 15 January 1842 in what is now the Melbourne suburb of Fitzroy, Victoria (at the time part of an area called Newtown in the then British colony of New South Wales), to Alexander MacKillop and Flora MacDonald.[6] Although she continued to be known as "Mary", when she was baptised six weeks later she received the names Maria Ellen.[7]

MacKillop's parents lived in Roybridge, Inverness-shire, Scotland, prior to emigrating to Australia.[8] MacKillop visited the village in the 1870s where the local Catholic church, St Margaret's, now has a shrine to her.

MacKillop's father, Alexander MacKillop, born in Perthshire,[9] had been educated at the Scots College in Rome and at Blairs College in Kincardineshire, for the Catholic priesthood but at the age of 29 left, just before he was due to be ordained. He migrated to Australia and arrived in Sydney in 1838.[6] MacKillop's mother, Flora MacDonald, born in Fort William, had left Scotland and arrived in Melbourne in 1840.[6] Her father and mother married in Melbourne on 14 July 1840. MacKillop was the eldest of their eight children. Her younger siblings were Margaret ("Maggie", 1843–1872), John (1845–1867), Annie (1848–1929), Alexandrina ("Lexie", 1850–1882), Donald (1853–1925), Alick (who died at 11 months old) and Peter (1857–1878).[6] Donald became a Jesuit priest and worked among the Aborigines in the Northern Territory. Lexie also became a Josephite.

MacKillop was educated at private schools and by her father. She received her First Holy Communion on 15 August 1850 at the age of nine. In February 1851, Alexander MacKillop left his family behind after having mortgaged the farm and their livelihood and made a trip to Scotland lasting some 17 months. Throughout his life he was a loving father and husband but never able to make a success of his farm. Most of the time the family had to survive on the small wages the children were able to bring home.

MacKillop started work at the age of 14 as a clerk in a stationery store in Melbourne.[6] To provide for her needy family, in 1860 she took a job as governess[10] at the estate of her aunt and uncle, Alexander and Margaret Cameron in Penola, South Australia where she was to look after their children and teach them.[6] Already set on helping the poor whenever possible, she included the other farm children on the Cameron estate as well. This brought her into contact with Fr Woods, who had been the parish priest in the south east since his ordination to the priesthood in 1857 after completing his studies at Sevenhill.

MacKillop stayed for two years with the Camerons before accepting a job teaching the children of Portland, Victoria in 1862. Later she taught at the Portland school and after opening her own boarding school, Bay View House Seminary for Young Ladies, now Bayview College, in 1864,[11] was joined by the rest of her family.

Founding of school and religious congregation

Fr Woods had been very concerned about the lack of education and particularly Catholic education in South Australia. In 1866, he invited MacKillop and her sisters Annie and Lexie to come to Penola and to open a Catholic school.[6] Woods was appointed director of education and became the founder, along with MacKillop, of a school they opened in a stable there. After renovations by their brother, the MacKillops started teaching more than 50 children.[12][13] At this time MacKillop made a declaration of her dedication to God and began wearing black.[14]

On 21 November 1866, the feast day of the Presentation of Mary, several other women joined MacKillop and her sisters. MacKillop adopted the religious name of Sister Mary of the Cross and she and Lexie began wearing simple religious habits. The small group began to call themselves the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart[6] and moved to a new house in Grote Street, Adelaide. There they founded a new school at the request of the bishop, Laurence Bonaventure Sheil OFM.[10] Dedicated to the education of the children of the poor, it was the first religious institute to be founded by an Australian.

The "Rule of Life" developed by Woods and MacKillop for the community emphasised poverty, a dependence on divine providence, no ownership of personal belongings, faith that God would provide and willingness to go where needed.[6] The "Rule of Life" was approved by Bishop Sheil. By the end of 1867, ten other women had joined the Josephites, who adopted a plain brown religious habit. Due to the colour of their attire and their name, the Josephite sisters became colloquially known as the "Brown Joeys".[14]

Expansion of the Sisters of St Joseph

In an attempt to provide education to all the poor, particularly in rural areas, a school was opened in Yankalilla, South Australia, in October 1867. By the end of 1869, more than 70 members of the Sisters of St Joseph were educating children at 21 schools in Adelaide and the country. MacKillop and her Josephites were also involved with an orphanage; neglected children; girls in danger; the aged poor; a reformatory (in Johnstown near Kapunda); and a home for the aged and incurably ill.[15] Generally, the Josephite sisters were prepared to follow farmers, railway workers and miners into the isolated outback and live as they lived.

In December 1869, MacKillop and several other sisters travelled to Brisbane to establish the order in Queensland.[13] They were based at Kangaroo Point and took the ferry or rowed across the Brisbane River to attend Mass at St Stephen's Cathedral. Two years later, she was in Port Augusta, South Australia for the same purpose. The Josephite congregation expanded rapidly and, by 1871, 130 sisters were working in more than 40 schools and charitable institutions across South Australia and Queensland.[15]

Excommunication

Bishop Sheil spent less than two years of his episcopate in Adelaide and his absences and poor health left the diocese effectively without clear leadership for much of his tenure. This resulted in bitter factionalism within the clergy and disunity among the lay community. After the founding of the Josephites, Sheil appointed Woods as director general of Catholic education.[16] Woods came into conflict with some of the clergy over educational matters[17] and local clergy began a campaign to discredit the Josephites. As well as allegations of financial incompetence, rumours were also spread that MacKillop had a drinking problem. In fact, it was widely known that she drank alcohol on doctor's orders to relieve the symptoms of dysmenorrhea, which often led to her being bedridden for days at a time. A 2010 investigation by the Revd Paul Gardiner, chaplain of the Mary MacKillop Penola Centre, found no evidence to support these allegations.[14]

In early 1870, MacKillop and her sister Josephites heard of allegations that Keating, of Kapunda parish to Adelaide's north, had been sexually abusing children.[18] The Josephites informed Father Woods, who in turn informed the vicar general Father John Smyth, who ultimately sent Keating back to Ireland.[18] The reason for Keating's dismissal was publicly thought to be alcohol abuse.[19] Keating's former Kapunda colleague, Father Charles Horan OFM, was angered by Keating's removal and there is evidence to suggest he sought revenge against Woods by attacking the Josephites.[18] Horan became acting vicar general after the death of Smyth in June 1870 and from this position sought to influence Bishop Sheil.[19] Horan met with Sheil on 21 September 1871 and convinced him that the Josephites' constitution should be changed in a way that could have left the Josephite nuns homeless; the following day, when MacKillop apparently did not accede to the request, Sheil excommunicated her, citing insubordination as the reason.[17][18] Though the Josephites were not disbanded, most of their schools were closed in the wake of this action.[17] Forbidden to have contact with anyone in the church, MacKillop lived with a Jewish family and was also sheltered by Jesuit priests. Some of the sisters chose to remain under diocesan control, becoming popularly known as "Black Joeys".[14][20]

On his deathbed, Sheil instructed Horan to lift the excommunication on MacKillop.[14] On 21 February 1872, he met her on his way to Willunga and absolved her in the Morphett Vale church.[21] Later, an episcopal commission completely exonerated her.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) said in September 2010 that MacKillop had been "banished after uncovering sex abuse" and cited Father Paul Gardiner in evidence of this. Gardiner described this suggestion as false, saying "Early in 1870, the scandal occurred and the Sisters of Saint Joseph reported it to Father Tenison Woods, but Mary was in Queensland and no one was worried about her." The executive producer of the ABC documentary said that the documentary did not suggest that MacKillop was excommunicated because of her role in exposure of child abuse: "At no stage ... is it claimed Mary MacKillop was excommunicated because she personally reported instances of abuse to the Catholic Church."[22]

Rome

After the acquisition of the Mother House in Kensington in 1872, MacKillop made preparations to leave for Rome to have the "Rule of Life" of the Sisters of St Joseph officially approved.

MacKillop travelled to Rome in 1873 to seek papal approval for the religious congregation and was encouraged in her work by Pope Pius IX.[12] The authorities in Rome made changes to the way Josephite sisters lived in regards to their commitment to poverty[15] and declared that the superior general and her council were the authorities in charge of the congregation.[21] They assured MacKillop that the congregation and their "Rule of Life" would receive final approval after a trial period.[12] The resulting alterations to the "Rule of Life" regarding ownership of property caused a breach between MacKillop and Woods, who felt that the revised document compromised the ideal of vowed poverty and blamed MacKillop for not getting the document accepted in its original form.[17][21] Before Woods' death on 7 October 1889, he and MacKillop were personally reconciled, but he did not renew his involvement with the congregation.[21]

While in Europe, MacKillop travelled widely to observe educational methods.[17]

During this period, the Josephites expanded their operations into New South Wales and New Zealand. MacKillop relocated to Sydney in 1883 on the instruction of Bishop Reynolds of Adelaide.[15]

Return from Rome

When Mackillop returned to Australia in January 1875, after an absence of nearly two years, she brought approval from Rome for her sisters and the work they did, materials for her school, books for the convent library, several priests and most of all, 15 new Josephites from Ireland. Regardless of her success, she still had to contend with the opposition of priests and several bishops. This did not change after her unanimous election as superior general in March 1875.[21]

The Josephites were unusual among Catholic church ministries in two ways. Firstly, the sisters lived in the community rather than in convents. Secondly the congregation's constitutions required administration by a superior general chosen from within the congregation rather than by the bishop, which was uncommon in its day. However, the issues which caused friction were that the Josephites refused to accept government funding, would not teach instrumental music (then considered an essential part of education by the church) and were unwilling to educate girls from more affluent families. This structure resulted in the sisters being forced to leave Bathurst in 1876 and Queensland by 1880 due to the local bishops' refusal to accept this working structure.[23][24][25]

Notwithstanding all the trouble, the congregation did expand. By 1877, it operated more than 40 schools in and around Adelaide, with many others in Queensland and New South Wales. With the help from Benson, Barr Smith, the Baker family, Emanuel Solomon and other non-Catholics, the Josephites, with MacKillop as their leader and superior general, were able to continue the religious and other good works, including visiting prisoners in jail.

After the appointment of Roger Vaughan as Archbishop of Sydney in 1877, life became a little easier for MacKillop and her sisters. Until his death in 1882, the Revd Joseph Tappeiner had given MacKillop his solid support and, until 1883, she also had the support of Bishop Reynolds of Adelaide.

After the death of Vaughan in 1883, Patrick Francis Moran became archbishop. Although he had a somewhat positive outlook toward the Josephites, he removed MacKillop as superior general and replaced her with Sister Bernard Walsh.[12][15][21]

Pope Leo XIII gave official approval to the Josephites as a congregation in 1885, with its headquarters in Sydney.[21]

On 31 May 1886, Mary MacKillop's mother, Flora MacKillop was travelling from Melbourne to Sydney in the SS Ly-ee-Moon, to visit Mary and another daughter who was also a nun. The ship struck a reef near the Green Cape Lighthouse. Flora, along with 70 others, died.[26]

Pope Leo XIII gave the final approval to the Sisters of Saint Joseph of the Sacred Heart in 1888.[12]

Although still living through alms, the Josephite sisters had been very successful. In South Australia, they had schools in many country towns including, Willunga, Willochra, Yarcowie, Mintaro, Auburn, Jamestown, Laura, Sevenhill, Quorn, Spalding, Georgetown, Robe, Pekina, Appila and several others. MacKillop continued her work for the Josephites in Sydney and tried to provide as much support as possible for those in South Australia. In 1883 the order was successfully established at Temuka in New Zealand, where MacKillop stayed for over a year.[27] In 1889 it was also established in the Australian state of Victoria.

During all these years MacKillop assisted Mother Bernard with the management of the Sisters of St Joseph. She wrote letters of support, advice and encouragement or just to keep in touch. By 1896, MacKillop was back in South Australia, visiting fellow sisters in Port Augusta, Burra, Pekina, Kapunda, Jamestown and Gladstone. That same year, she travelled again to New Zealand, spending several months in Port Chalmers and Arrowtown in Otago.[27][28] During her time in New Zealand with the Sisters of St Joseph, a school was established in Arrowtown, near Queenstown, South Island. Located in the grounds of St Patrick's Church, the small yellow cottage now known as Mary MacKillop cottage was originally built as a miner's house around 1870. It was bought by the church and incorporated into the church school in 1882 and then in 1897, Sister Mary MacKillop had the cottage and some of the school converted to a convent for the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart who worked in New Zealand and Australia.

In 1897, Bishop Maher of Port Augusta arranged for the Sisters of St Joseph to take charge of the St Anacletus Catholic Day School at Petersburg (now Peterborough).

MacKillop founded a convent and base for the Sisters of St Joseph in Petersburg on 16 January 1897. "On January 16th, 1897, the founder of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, Mother Mary of the Cross,[17] arrived in Petersburg to take over the school. She was accompanied by Sister Benizi (who was placed in charge of the school), Sister M. Joseph, Sister Clotilde and Sister Aloysius Joseph. They were met at the station by Rev. Father Norton who took them to the newly blessed convent, purchased for them on Railway Terrace."[29] The property at 40 Railway Terrace is identified as the convent by a plaque placed by the Catholic diocese of Peterborough.[29]

After the death of Mother Bernard, MacKillop was once more elected unopposed as superior general in 1899,[12] a position she held until her own death. During the later years of her life she had many problems with her health which continued to deteriorate. She suffered from rheumatism and after a stroke in Auckland, New Zealand in 1902, became paralysed on her right side. For seven years, she had to rely on a wheelchair to move around, but her speech and mind were as good as ever and her letter writing had continued unabated after she learned to write with her left hand. Even after suffering the stroke, the Josephite nuns had enough confidence in her to re-elect her in 1905.

Death

MacKillop died on 8 August 1909 at the Josephite convent in North Sydney.[10] The Archbishop of Sydney, Cardinal Moran, said: "I consider this day to have assisted at the deathbed of a saint."[14] She was laid to rest at the Gore Hill cemetery, a few kilometres up the Pacific Highway from North Sydney.

After MacKillop's burial, people continually took earth from around her grave. As a result, her remains were exhumed and transferred on 27 January 1914 to a vault before the altar of the Virgin Mary in the newly built memorial chapel in Mount Street, North Sydney.[30] The vault was a gift of Joanna Barr Smith, a lifelong friend and admiring Presbyterian.

Canonisation and commemoration

In 1925, the Mother Superior of the Sisters of St Joseph, Mother Laurence, began the process to have MacKillop declared a saint and Michael Kelly, Archbishop of Sydney, established a tribunal to carry the process forward. The process for MacKillop's beatification began in 1926, was interrupted in 1931 but began again in April 1951 and was closed in September of that year. After several years of hearings, close examination of MacKillop's writings and a 23-year delay, the initial phase of investigations was completed in 1973.[31] After further investigations, MacKillop's "heroic virtue" was declared in 1992. That same year, the church endorsed the belief that Veronica Hopson, apparently dying of leukaemia in 1961, was cured by praying for MacKillop's intercession; MacKillop was beatified on 19 January 1995 by Pope John Paul II.[12] For the occasion of the beatification, the Croatian-Australian artist Charles Billich was commissioned to paint MacKillop's official commemorative.[32]

On 19 December 2009, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints issued a papal decree formally recognising a second miracle, the complete and permanent cure of Kathleen Evans[33] of inoperable lung and secondary brain cancer in the 1990s.[34] Her canonisation was announced on 19 February 2010 and subsequently took place on 17 October 2010.[35] This made her the first Australian to be recognised as a saint by the Catholic Church.

In the week leading up to her canonisation, the Australian federal government announced that it was protecting the use of MacKillop's name for commercial purposes.[36] According to a statement from the office of the Prime Minister of Australia, Julia Gillard, the only other individual Australian whose name has similar protection is Australian cricket legend Sir Donald Bradman.[37] Australia Post issued an official postage stamp to recognise MacKillop's canonisation.[38]

An estimated 8,000 Australians were present in Vatican City to witness the ceremony.[39] The Vatican Museum held an exhibition of Aboriginal art to honour the occasion titled "Rituals of Life".[40] The exhibition contained 300 artifacts which were on display for the first time since 1925.[41]

Along with MacKillop, sainthood was also approved for Saint André Bessette, a Canadian Holy Cross Brother; Stanisław Kazimierczyk, a 15th-century Polish priest; Italian nuns Giulia Salzano and Camilla Battista da Varano; and Spanish nun Candida Maria of Jesus.

MacKillop is remembered in numerous ways, particularly in Australia. Many things have been named for her, including the electoral district of MacKillop in South Australia and several MacKillop collegess. In 1985, the Sisters of St Joseph approached one of Australia's foremost rose growers to develop the Mary MacKillop Rose.[42] MacKillop was the subject of the first of the "Inspirational Australians" one dollar coin series, released by the Royal Australian Mint in 2008.[43]

Representations film, drama, music and literature

Several Australian composers have written sacred music to celebrate Mary MacKillop. In 2009 Nicholas Buc was commissioned by the Shire of Glenelg to write an hour-long cantata mass for the centenary of the death of Mary MacKillop.[44] It was premiered by the Royal Melbourne Philharmonic in Portland, Victoria.[45] The "Mass of Mary McKillop" is a Mass setting for congregational singing, composed by Joshua Cowie.[46][47] Hymns specifically used in St Mary of the Cross celebrations including A Saint for Today and Mary MacKillop, Woman of Australia by Josephite Sister Margaret Cusack, and If I Could Tell The Love of God, In Love God Leads Us and Psalm 103 by Jesuit Priest Christopher Willcock.[48]

MacKillop is also the subject of several artistic productions, including the 1994 film Mary, directed by Kay Pavlou with Lucy Bell as MacKillop;[49] Her Holiness, a play by Justin Fleming;[50] and MacKillop, a dramatic musical created by Victorian composer Xavier Brouwer[51] and first performed for pilgrims at World Youth Day 2008 in Melbourne.[52] Novelist Pamela Freeman's The Black Dress is a fictionalised biography of MacKillop's childhood and young adulthood.[53]

In 2000, the State Transit Authority named a SuperCat ferry after MacKillop.

See also

References

- ↑ "St Mary of the Cross MacKillop Named Second Patron of Australia". Sydney Catholic. Archdiocese of Sydney. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "St. Mary MacKillop". Catholic Online. Catholic Online. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ MacKillop has become Australia's first saint, ABC News, 20 December 2009

- ↑ "Canonization for Mary MacKillop underway". Sydney Morning Herald. 17 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Nun becomes first Australian saint". Al Jazeera. 17 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mary's Story: Beginnings, retrieved 25 September 2010

- ↑ Pickles, Katie (December 2005). "Colonial Sainthood in Australasia". National Identities. 7 (4): 401. doi:10.1080/14608940500334457.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Martin (18 October 2010). "Saintly daughter of Scotland honoured". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, Caroline (15 August 2010). "Sainthood". The Herald. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 Saint Mary MacKillop, http://www.sosj.org.au. Retrieved 20 October 2008

- ↑ "Bayview College – Home". Bayview.vic.edu.au. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Blessed Mary of the Cross". Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- 1 2 "Mary's Story: Growth". Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "In Her Own Hand", The Advertiser, pp. 8, 89; 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mary MacKillop. Retrieved 20 October 2008 Archived 22 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Sheil, Laurence Bonaventure (1815–1872)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Osmund Thorpe, 'MacKillop, Mary Helen (1842–1909)', Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 21 October 2008

- 1 2 3 4 "MacKillop banished after uncovering sex abuse". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 September 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- 1 2 Fennessy, Ignatius (1999). "Hugh Charles Horan of Galway and Mother Mary MacKillop". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society. Galway: Galway Archaeological & Historical Society. 51: 140–146.

- ↑ "'Black Joeys' to meet in Hunter Valley". Cathnews.acu.edu.au. 2005-04-15. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mary's Story: Challenge, retrieved 25 September 2010

- ↑ Rawlinson, Clare; Madden, James (7 October 2010). "Priest denies making claims about MacKillop's excommunication". The Australian. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ↑ Rosa MacGinley Partition And Amalgamation Among Women’s Religious Institutes In Australia, 1838–1917

- ↑ Henningham, Nikki (5 June 2009). "Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart". The Australian Women's Register. National Foundation for Australian Women and the University of Melbourne. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ↑ "Timeline, Moments in the Life of Saint Mary Mackillop". Saint Mary MacKillop. Sisters of Saint Joseph. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Flora Mackillop".

- 1 2 Owens, S. "Mary McKillop in New Zealand", Marist Messenger NZ, 1 October 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ↑ Gilchrist, Shane (16 October 2010). "A blessing on both sides". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- 1 2 The Catholic Story, of Peterborough. Peterborough Centenary Committee. 1976. cited in "Mary MacKillop Lane, Peterborough, South Australia". Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart website. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ↑ "www.marymackillopplace.org.au/chapel". Marymackillopplace.org.au. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ B. Bennett, Mary MacKillop: A rocky road to canonisation, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 31/2 (2010/11), 60-67.

- ↑ Charles Billich – Arts Archived 6 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Maley, Jacqueline (11 January 2010). "Cancer survivor Kathleen speaks of her Mary miracle". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ Maley, Jacqueline; O'Grady, Desmond (20 December 2009). "Our Mother Mary: a model for the world". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ↑ "Date set for MacKillop's sainthood". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ↑ Karvelas, Patricia (11 October 2010). "Mary Mackillop to join Don Bradman on protected list". The Australian. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ↑ "Government to protect MacKillop's name". Sydney, Australia: ABC News. 11 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ↑ "World Stamp News". World Stamp News. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ Alberici, Emma (18 October 2010). "Australians celebrate Mary's canonisation". ABC News. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ Alberici, Emma (15 October 2010). "First Australians celebrate first Australian saint". ABC News. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "Rudd leads delegation to Vatican". Big Pond News. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "Mary MacKillop Rose". Helpmefind.com. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Mint Issue 76 > 2008 $1 uncirculated coin – Mary MacKillop Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 21 October 2008

- ↑ "Bio — Nicholas Buc". Nicholasbuc.com. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ "Celebrations For Mary Mackillop - Portland" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ "Mass of Mary MacKillop Music Book". Asonevoice.com.au. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ "Music". Joshua Cowie. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ "Saint Mary MacKillop | Resources". Marymackillop.org.au. 2010-10-01. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ Mary on IMDb

- ↑ Her Holiness, review by Brett Casben at AustralianStage.com 2 June 2008)

- ↑ Mother Mary set to music. (13 May 2009). Charrison, Emily. Eastern Courier. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ "Mary the saintly musical". ABC News. 23 February 2010.

- ↑ "Pamela Freeman: Mary McKillop and The Black Dress". Pamelafreemanbooks.com. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mary MacKillop. |

- Mary MacKillop official website

- Sisters of Saint Joseph of the Sacred Heart official website

- Mary MacKillop Place official website

- Mary MacKillop Penola Centre official website

- MacKillop, a musical by Xavier Brouwer

- MacKillop Family Services website

- O Mother Mary of the Cross, a hymn to St. Mary of the Cross, text by Veronica Brandt, music by Charles H. Giffen.

- MacKillop, Mary Helen in The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia

Further reading

- Paton, Margaret (2010). Mary MacKillop: The ground of her loving. London: Darton Longman Todd. ISBN 978-0-232-52799-5.