Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley

| Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1833 West Bromwich, Staffordshire, England |

| Died |

26 May 1904 Monmouth, Monmouthshire, Wales |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Antiquarian, author, painter, school governor |

| Board member of | Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls |

| Spouse(s) | William Oakeley |

Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley (1833–1904) was an English antiquarian, author, and painter known for her work in Bristol and south-east Wales. She was a governor of the Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls and the mother of nine children.

Background

Mary Ellen Bagnall, eldest daughter and heiress of John Bagnall[1] and his wife Mary Ann Robbins,[2] was born in 1833 in West Bromwich, Staffordshire.[3][4][5] Her father John Bagnall (1794–1840), eldest son of John Bagnall, had become the senior member of John Bagnall and Sons, upon the death of his father in 1829.[6] The firm had been established by his father, who had brought five of his sons into partnership with him in 1828, the year before his death. The company had extensive collieries and ironworks. Mary Ellen's father John died on 4 February 1840.[6]

In 1841, Mary Ellen lived in West Bromwich with her mother, younger sisters Jane and Kate, and seven servants.[3] By 1851, the family had moved to Monmouth in Wales, where she resided with her widowed mother, two sisters, and staff of six.[4] Mary Ellen Bagnall married William Oakeley (1822–1912), son of Thomas and Elizabeth Oakeley, on 31 August 1853 in Monmouth.[1] Their marriage was registered in Monmouth in the third quarter of 1853.[7] Mary Ellen and her husband resided in the village of Penallt, near Monmouth, with their family and household servants, at the time of the 1861 and 1871 census enumerations. She was the mother of nine children, James Bagnall, William Ralph, Mary Beatrice, John Lewis, Jane Parnel, Elizabeth Blanche, Alexandra Ethel, Kemeys Leoline, and, the archer, Richard Henry.[8][9][10]

Clifton Antiquarian Club

Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley was a member of or associated with a number of societies in England and Wales. She took an interest in antiquarianism and numismatics, and penned numerous articles and pamphlets on antiquarian topics for societies. These included the 1902 '"Monnow Bridge Tower: Description of the Tower and Its History, with Copy of Old Documents in Connection Therewith" (Volume 1 of Monmouthshire pamphlets).[11][12][13]

On 8 January 1891, her husband Reverend William Oakeley was elected to membership of the Clifton Antiquarian Club that was based in Bristol.[14] As a woman, Mary Ellen was excluded from membership in that society.[15] However, she was still able to submit learned papers to the society. In addition, the historian was able to participate in the day excursions that the club sponsored.[15] On 20 July 1889, the club undertook an excursion to Tintern Abbey and Monmouth. Bagnall-Oakeley and her husband served as guides for the Monmouth portion of the excursion. The group visited St. Thomas Church, the gatehouse on the Monnow Bridge (pictured), the ruins of Monmouth Castle, the Church of St. Mary, and "Geoffrey's" Window.[16]

All of the papers submitted to the Clifton Antiquarian Club are maintained in the seven leather-bound volumes of the Proceedings and cover the years 1884 to 1912. The five papers that Mary Ellen submitted to the Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club cover the period from 1887–1888 (in Volume 1 of the Proceedings) to 1895 (in Volume 3 of the Proceedings). In chronological order, they include:[17]

- "Notes on the Stitches Employed in the Embroidery of the Copes." (Read on 20 December 1887, appeared in Volume 1)[18]

- "Notes on Round Towers." (Read on 12 October 1891, appeared in Volume 2)[19]

- "Early Christian Settlements in Ireland." (Read on 20 November 1893, appeared in Volume 3)[20]

- "A Week in the Aran Islands." (Read on 22 November 1894, appeared in Volume 3)[20]

- "On a Great Hoard of Roman Coins." (Read on 28 January 1896, appeared in Volume 3)[20]

Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society

Bagnall-Oakeley was a member of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society where she made presentations on a variety of antiquarian subjects. The society was founded in 1876 and, similar to the Clifton Antiquarian Club, offered a program of lectures and excursions.[21] In 1889, she presented a paper entitled "Sanctuary knockers" (or "hagodays") which detailed the history of 12th to 14th century church door knockers, the use of which allowed anyone to claim sanctuary at any hour.[22] All of the papers that she submitted are maintained in the Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. The historian submitted sixteen papers over a period of twenty years, from 1881–1882 (Volume 6 of the Transactions) to 1902 (Volume 25 of the Transactions). Her presentations to the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, in chronological order, include:[23][24][25]

- "On Roman Coins found in the Forest of Dean." (Volume 6, 1881 – 1882)

- "On Some Sculptured Effigies of Ecclesiastics in Gloucestershire." (Volume 9, 1884 – 1885)

- "Ancient Church Embroidery in Gloucestershire." (Volume 11, 1886 – 1887)

- "Ancient Church Embroidery in Gloucestershire (addendum)." (Volume 11, 1886 – 1887)

- "Sanctuary Knockers." (Volume 14, 1889 – 1890)

- "On the Monumental Effigies of the Family of Berkeley." (Volume 15, 1890 – 1891)

- "Ancient Sculptures in the South Porch of Malmesbury Abbey Church." (Volume 16, 1891 – 1892)

- "Ladies' Costume in the Middle Ages as represented on Monumental Effigies and Brasses." (Volume 16, 1891 – 1892)

- "On Some Pre-Roman Sculptured Slabs At Daglingworth Church." (Volume 17, 1892 – 1893)

- "The Dress of Civilians in the Middle Ages, from Monumental Effigies." (Volume 18, 1893 – 1894)

- "Notes on a great Hoard of Roman Coins found at Bishop's Wood." (Volume 19, 1894 – 1895)

- "Grosmont Castle (pictured), Skenfrith Castle (pictured) and Church, Pembroke Castle." (Volume 20, 1895 – 1897)

- "Monumental Effigies in Bristol and Gloucestershire." (Volume 25, 1902)

- "Rural Deanery of South Forest." (Volume 25, 1902)

- "Rural Deanery of Bitton." (Volume 25, 1902)

- "Rural Deanery of Cheltenham." (Volume 25, 1902)

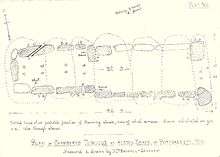

Illustrations for research papers

In addition to her antiquarian interests, Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley was also an accomplished artist. While she is most known for her watercolours, she also produced drawings to accompany some of her research papers. While some were artistic illustrations, others were more technical, and did not necessarily accompany only her own research. As mentioned above, women were allowed to join the excursions of the Clifton Antiquarian Club.[15] However, Bagnall-Oakeley not only accompanied men on the day trips; she actively participated in the investigations. An example of this is the excursion sponsored jointly by the Clifton Antiquarian Club and the Monmouthshire and Caerleon Antiquarian Association on 22 August 1888. The excursion is described in the postscript to the 1888 paper authored by the Reverend William Oakeley, "The Chambered Tumulus at Heston Brake, Monmouthshire," found in Volume 2 of the Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club.[26] On that day, the tumulus at the site Heston Brake in Portskewett was opened and examined under the direction of the members of the two associations. There was evidence that the tumulus had been previously disturbed. The few relics which remained, fragments of pottery and human bones and teeth, are now in the Caerleon Museum, the National Roman Legion Museum. At the time of that 1888 excavation, Bagnall-Oakeley made measurements of all the components of the tumulus. Her illustration (pictured), which accompanies her husband's paper, is entitled, "Plan of Chambered Tumulus at Heston Brake, nr Portskewett, Mon."[26] Illustrations also accompanied some of her own research papers. An example is "Notes on Round Towers" which was read on 12 October 1891 and appeared in Volume 2 of the Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club. The author examined the topic of round towers in Ireland, Scotland, Germany, France, and Italy. Bagnall-Oakeley's drawing of the Church of San Lorenzo in Verona, Italy (pictured) is included with that research paper.[27]

Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls

The Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls (pictured) was founded in 1892 by The Worshipful Company of Haberdashers.[28][29] The school was established courtesy of the charity founded by the haberdasher William Jones prior to his 1615 death.[28][30] Jones made The Worshipful Company of Haberdashers the trustee of his foundation.[28][30] The William Jones Foundation funded a number of schools and alms houses, including the Monmouth School and the Monmouth Alms Houses.[28][30] At the time that the Monmouth School for Girls was established, Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley was appointed as a governor, along with three other women, and was responsible for managing the school.[11] The structure of Divisions was introduced in 1913, with matriculating girls assigned randomly to Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, or Wagner.[31] Divisions were later replaced by Houses, with each House named in honour of one of the four original school governors, and students assigned on a geographical basis, rather than randomly.[31] One of the Houses is named Bagnall-Oakeley in honour of the former governor who served the school.[11][31] Students in her House may receive a Certificate of Bagnall Endeavours for a special accomplishment or an Order of Bagnall Excellence for an outstanding accomplishment.[11]

Watercolour paintings

A book of Bagnall-Oakeley's watercolours, entitled Nooks and corners of old Monmouthshire: A catalogue of watercolour paintings by Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley (1833–1904), is held by the Monmouth Museum.[32] Her collection of paintings is also at the Monmouth Museum at Market Hall on Priory Street.[33] They include the watercolour, "Forge" (pictured).

Later family life

Among the responsibilities of her husband, the Reverend William Oakeley, was the spiritual welfare of those in the William Jones Newland Alms Houses in Newland, Gloucestershire.[11] The bequest from William Jones to the town of Newland had also created a lectureship, which was held by Reverend Oakeley.[34] Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley was a staunch supporter of women's suffrage.[11] Her husband William may have been ahead of his time. He periodically used Mary Ellen's conjoined surname Bagnall-Oakeley as his own. Examples include his probate records,[35] the 1911 Wales Census,[10] and the paper "The Chambered Tumulus at Heston Brake, Monmouthshire" (Volume 2, 1888 – 1889)[17] submitted to the Clifton Antiquarian Club. At the time of the 1881 and 1891 census enumerations, Mary Ellen lived in Newland with her family and servants.[36][37] By 1901, the family had moved to Monmouth, where the antiquarian resided with her clergyman husband William, single daughter Mary, and household staff of five.[38] Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley died on 26 May 1904 in Monmouth.[11][39] After her death, her widowed husband and daughter Mary continued to reside in Monmouth, where William died in 1912.[10][35] Mary Ellen and her husband were both interred in Monmouth Cemetery.[11][33]

References

- 1 2 "Marriages". The Gentleman's Magazine, Volume 40. W. Pickering. 1853. p. 524. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Bagnall, John. "England & Wales Marriages, 1538–1940". ancestry.com. British Isles Vital Records Index, 2nd Edition (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- 1 2 Bagnall, Mary. "1841 England Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1841. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- 1 2 Bagnall, Mary E. "1851 Wales Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1851. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- ↑ Oakeley, Mary Ellen B. "England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837–1915". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- 1 2 "Memoirs" (PDF). icevirtuallibrary. Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE). Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Bagnall, Mary Ellen. "England & Wales, FreeBMD Marriage Index: 1837–1915". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- ↑ Cokeley, Mary Ellen. "1861 Wales Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1861. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- ↑ Oakaley, Mary Ellen. "1871 Wales Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1871. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- 1 2 3 Bagnall-Oakeley, William. "1911 Wales Census". Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911. The National Archives of the UK, 1911 (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Bagnall-Oakeley". hmsg.co.uk. Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ "Monnow Bridge Tower: Description of the Tower and Its History, with Copy of Old Documents in Connection Therewith". books.google.com. Google. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ↑ "Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley". amazon.co.uk. amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Alfred Edmund Hudd, ed. (1893). Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club for 1888–1893, Vol. II. Clifton Antiquarian Club. p. 175. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 "History and Mission Statement". cliftonantiquarian.co.uk. Clifton Antiquarian Club. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Alfred Edmund Hudd, ed. (1893). Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club for 1888–93, Vol. II. Clifton Antiquarian Club. pp. 89–90. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- 1 2 "Index to the proceedings, Volumes 1–7, 1884–1912" (PDF). cliftonantiquarian.co.uk. Clifton Antiquarian Club. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Alfred Edmund Hudd, ed. (1888). Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club for 1884–88, Vol. I. Clifton Antiquarian Club. pp. 229, 238. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Alfred Edmund Hudd, ed. (1893). "Notes on Round Towers". Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club for 1888–93, Vol. II. Clifton Antiquarian Club. p. 142. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 Alfred Edmund Hudd, ed. (1896). Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club for 1893–96, Vol. III. Clifton Antiquarian Club. pp. 81, 99, 162. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "About the Society". bgas.org.uk. The Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ↑ John MacLean, ed. (1889–1890). "Sanctuary Knockers". Transactions – Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Bristol: C. T. Jefferies and Sons, Limited. pp. 131–140. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ "Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Contents Pages for Vols. 1–10 (1876–1886)". bgas.org.uk. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ "Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Contents Pages for Vols. 11–20 (1887–1895)". bgas.org.uk. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ "Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Contents Pages for Vols. 21–30 (1896–1907)". bgas.org.uk. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- 1 2 Rev William Bagnall-Oakeley, M.A. "The Chambered Tumulus at Heston Brake, Monmouthshire" (PDF). cliftonantiquarian.co.uk. Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club, Volume 2. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Arthur Edmund Hudd, ed. (1893). "Notes on Round Towers". Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club for 1888–1893, Vol. II. The Clifton Antiquarian Club. pp. 142–151. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "History". habs-monmouth.org. Haberdashers' Monmouth Schools. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ "The Haberdashers' Company". hmsg.co.uk. Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 William Meyler Warlow (1899). A history of the charities of William Jones (founder of the "Golden lectureship" in London), at Monmouth & Newland. W. Bennett. pp. 18–54. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 "School Houses". hmsg.co.uk. Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Bagnall-Oakeley, Mary Ellen. Nooks and corners of old Monmouthshire: A catalogue of watercolour paintings by Mary Ellen Bagnall-Oakeley (1833–1904). Monmouth Museum, Market Hall, Priory St.

- 1 2 Label in Monmouth Museum, read April 2012.

- ↑ "Newland and Tythings 1876". freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Morris & Co. Directory & Gazetteer. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- 1 2 Bagnall-Oakeley, William. "England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1861–1941". ancestry.com. Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice in England. Principal Probate Registry (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- ↑ Oakley, Mary E. "1881 England Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1881. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- ↑ Oakley, Mary E B. "1891 England Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1891. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- ↑ Oakley, Hary (sic) B. "1901 Wales Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

- ↑ Bagnall-Oakeley, Mary Ellen. "England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1861–1941". ancestry.com. Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice in England. Principal Probate Registry (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).