Martial eagle

| Martial eagle | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Maasai Mara, Kenya | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Polemaetus Heine, 1890 |

| Species: | P. bellicosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Polemaetus bellicosus (Daudin, 1800) | |

| |

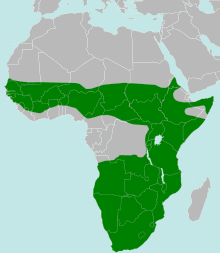

| Approximate range in green | |

The martial eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus) is a large eagle native to sub-Saharan Africa.[2] It is the only member of the genus Polemaetus. A species of the booted eagle sub-family (Aquillinae), it has feathering over its tarsus. One of the largest and most powerful species of booted eagle, it is a fairly opportunistic predator that varies it prey selection between mammals, birds and reptiles. Its hunting technique is unique as it is one of few eagle species known to hunt primarily from a high soar, by stooping on its quarry.[3] An inhabitant of wooded belts of otherwise open savanna, this species has shown a precipitous drop in the last few centuries due to a variety of factors. The martial eagle is one of the most persecuted bird species in the world. Due to its habit of taking livestock and regionally valuable game, local farmers and game wardens frequently seek to eliminate martial eagles, although the effect of eagles on this prey is almost certainly considerably exaggerated. Currently, the martial eagle is classified with the status of Vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN.[1][4][5]

Range

The martial eagle can be found in most of sub-Saharan Africa, wherever food is abundant and the environment favourable. With a total estimated distribution of about 26,000 km2 (10,000 sq mi), it is fairly widely distributed in the continent, having a somewhat broader range than species like the crowned eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus) and the Verreaux's eagle (Aquila verreauxii).[6] Although never common, greater population densities do exist in southern Africa and in some parts of east Africa. Martial eagles tend to be rare and irregular in west Africa but are known to reside in Senegal, The Gambia and northern Guinea-Bissau, southern Mali and the northern portions of Ivory Coast and Ghana. From southern Niger and eastern Nigeria the species is distributed spottily through Chad, Sudan and the Central African Republic as well as the northern, eastern, and southern portions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In east Africa, they range from northwestern Somalia and Ethiopia more or less continuously south through Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and in southern Africa from Angola, Zambia, Malawi and southern Mozambique to South Africa.[2] Some of the larger remaining populations are known to persist in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Generally, these birds are more abundant in protected areas such as Kruger National Park and Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park in South Africa, or Etosha National Park in Namibia.[7]

Taxonomy

_-_Flickr_-_Lip_Kee_(4).jpg)

The Accipitridae (hereafter accipitrids) family is by far the most diverse family of diurnal raptors in the world with more than 230 currently accepted species.[8] As a member of the booted eagle sub-family, Aquilinae, it is one of the roughly 15% extant species of the family to have feathers covering its legs.[2] This may be a useful feature for distinguishing these species from other eagles and raptors, as they are present even in tropical species such as the martial eagle.[9] Under current classifications, booted eagles consist of approximately 38 living species that are distributed in every continent inhabited by the accipitrids, which excludes only the continent of Antarctica. Just under half of the living species of booted eagle are found in Africa.[10][11] Studies have been conducted on the mitochondrial DNA of most booted eagle species, including the martial eagle, in order to gain insight on how the sub-family is ordered and which species bear relation to one another. DNA testing in the 1980s indicated the martial eagle was a specialized off-shoot of the small-bodied Hieraaetus eagles and one study went so far as to advocate that the martial eagle be included in the genus.[10] However, more modern and comprehensive genetic testing has shown that the martial eagle is extremely distinct from other living booted eagles and diverged from other existing genera several million years ago.[11][12] Genetically, the martial eagle fell between two other species in monotypical genera, the African long-crested eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis) and the Asian rufous-bellied eagle (Lophotriorchis kienerii), that similarly diverged long ago from other modern species. Given the disparity of this species’ unique morphology and that the two aforementioned most closely related living species are only about as large as the bigger buzzards, the unique heritage of the martial eagle is considered even superficially evident.[11][12] There are no subspecies of martial eagle and the species varies little in appearance and genetic diversity across its distribution.[2][5]

Description

The martial eagle is a very large eagle. In total length, it can range from 78 to 96 cm (31 to 38 in), with an average of approximately 85.5 cm (33.7 in).[2][13] Its total length – in comparison to its wingspan – is restricted by its relatively short tail. Nonetheless, it appears to be the sixth or seventh longest living eagle species.[2] The wingspan of martial eagles can range from 188 to 260 cm (6 ft 2 in to 8 ft 6 in).[2][8][14] Average wingspans have been claimed of 205 cm (6 ft 9 in) and 207.5 cm (6 ft 10 in) for the species, however ten measured martial eagles in the wild were found to average 211.9 cm (6 ft 11 in) in wingspan. Thus, the martial eagle appears to average fourth in wingspan among living eagles, behind only the Steller's sea-eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus), the white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) and the wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax), in roughly that order.[2][13][15][16][17] For a species that is fairly homogeneous in its genetic make-up, the body mass of martial eagles is surprisingly variable. To some extent, the variation of body masses in the species is contributable to considerable reverse sexual dimorphism as well as varying environmental conditions of various eagle populations.[18] Unsexed martial eagles from various studies have been found to have weighed an average of 3.93 kg (8.7 lb) in 17 birds, 3.97 kg (8.8 lb) in 20 birds and 4.23 kg (9.3 lb) in 20 birds while the average weight of martial eagles shot by game wardens in the early 20th century in South Africa was listed as 4.71 kg (10.4 lb).[15][18][19][20][21] In weight range, the martial eagle broadly overlaps in size with the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) and Verreaux's eagle (and is even exceeded by them in maximum known body mass). Based on numerous studies, the martial eagle appear to average mildly heavier than the Verreaux's eagle but (derived from the globally combined body mass of its various races), the mean body masses of golden and martial eagles are identical at approximately 4.17 kg (9.2 lb). The renders the golden and martial eagles as tied as the largest African eagles (by body mass but not in total length or wingspan, in which the martial bests the golden), as well as the heaviest two species of booted eagle in the world and as tied as the sixth heaviest eagles in the world, after the three largest species of sea eagle (Steller's being the heaviest extant, the others ranking 4th and 5th), the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and the Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi).[2][15][18][20][22][23] The longest African eagle (and second longest booted eagle after the wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax)) is the crowned eagle by virtue of its relatively longer tail, as its body weight is slightly less than these three heaviest booted eagle species.[2][20]

Sexual dimorphism

Martial eagles are highly sexual dimorphic. While females average about 10% larger in linear dimension, in body mass, the sexual dimorphism of martial eagles is more pronounced. Males reportedly can weigh from 2.2 to 3.8 kg (4.9 to 8.4 lb), with seven males averaging 3.17 kg (7.0 lb) and five averaging 3.3 kg (7.3 lb).[22][24][25] On the other, females can weigh from 4.45 to 6.5 kg (9.8 to 14.3 lb), with seven females averaging 4.95 kg (10.9 lb). Elsewhere, a claim was made of an average of 5.2 kg (11 lb) almost certainly describes female specimens.[22][26] Reports of males weighing as much as 5.1 kg (11 lb) and females weighing as little as 3.9 kg (8.6 lb) are known but may possibly represent individual eagles misidentified by sex, which is reportedly not infrequent due to mistakes in the field.[25][27][28] Thus the dimorphism by weight is roughly 36% in favor of the female, which is unusually out-of-sync with the linear differences between the sexes. For example, the greater spotted eagle (Clanga clanga), the most sexual dimorphic booted eagle overall with a linear difference between the sexes of 20%, has around the same level of sexual dimorphism by body mass as the martial eagle which show about half as much linear dimorphism.[2][24] In standard measurements, male martial eagles measure 560 to 610 mm (22 to 24 in) in wing chord size, 273 to 280 mm (10.7 to 11.0 in) in tail length and 97 to 118 mm (3.8 to 4.6 in) in tarsus length. Meanwhile, females measure 605 to 675 mm (23.8 to 26.6 in) in wing chord, 280 to 320 mm (11 to 13 in) in tail length and 114 to 130 mm (4.5 to 5.1 in) tarsal length.[2] Overall, the bulk and much more massive proportions of females, which include more robust feet and longer tarsi, may at times allow experienced observers to sex lone birds in the wild.[3][25]

Colouring and field identification

_juvenile_(17142198408).jpg)

The adult's plumage consists of dark grey-brown coloration on the upperparts, head and upper chest, with an occasional slightly lighter edging to these feathers. The body underparts are feathered white with sparse but conspicuous blackish-brown spotting. The underwing coverts are dark brown, with the remiges being pale streaked with black, overall imparting the wings of adults a dark look. The underside of the tail has similar barring as the remiges while the upperside is the same uniform brown as the back and upperwing coverts. The eyes of mature martial eagles are rich yellow, while the cere and large feet pale greenish and the talons black. Martial eagles have a short erectile crest, which is typically neither prominent nor flared (unlike that of the crowned eagle) and generally appears as an angular back to a seemingly flat head. This species often perches in a quite upright position, with its long wings completely covering the tail, causing it be described as “standing” rather than “sitting” on a branch when perched. In flight, martial eagles bear long broad wings with relatively narrow rounded tips that can appear pointed at times depending on how the eagle is holding its wings. It is capable of flexible beats with gliding on flattish wings, or slightly raised in a dihedral. This species often spends much a large portion of the day on the wing, more so than probably any other African eagles, and often at a great height.[2][3][8] Juvenile martial eagles are conspicuously distinct in plumage with a pearly gray colour above with considerable white edging, as well as a speckled grey effect on crown and hind neck. The entire underside is conspicuously white. The wing coverts of juveniles are mottled grey-brown and white, with patterns of bars on primaries and tail that are similar to adult but lighter and greyer. In the 4th or 5th years, a very gradual increase to brownish feather speckling is noted but the back and crown remain a fairly pale grey. At this age, there may be increasing spots on throat and chest which coalesce into a gorget and some spots on abdomen may variably manifest as well. The eyes of juveniles are dark brown. This species reaches adult plumage by its seventh year with the transition to adult plumage happening quite rapidly after many years in a little-changing juvenile plumage.[2][3][29]

There are few serious identification challenges for the species. The black-chested snake eagle (Circaetus pectoralis) is similar in overall colouring (despite its name it is brown on the chest and the back, being no darker than the adult martial eagle) to martial eagles but is markedly smaller, with a relatively more prominent, rounded head with large eyes, plain, spotless abdomen, bare and whitish legs. In flight, the profile of the snake eagle is quite different with nearly white (rather than dark brown) flight feathers and much smaller, narrower wings and a relatively larger tail. For juveniles, the main source for potential confusion is the juvenile crowned eagle, which also regularly perches in an erect position. The proportions of crowned eagles are quite distinct from martial eagles as they have much shorter wings and a distinctly longer tail. The juvenile crowned eagle has a whiter head, more scaled back, and spotted thighs and legs lacking in the martial eagle. Beyond their distinct flight profile by wing and tail proportions, crowned eagles have whiter and more obviously banded flight-feathers and tail. Other large immature eagles in Africa tend to be much darker and more heavily marked both above and below than martial eagles.[2][3]

Predatory Physiology

Martial eagles have been noted as remarkable for their extremely keen eyesight (3.0–3.6 times human acuity). Due to this power, they can spot potential prey from a very great distance, having been known to be able to spot prey from as far as 5 to 6 km (3.1 to 3.7 mi) away.[2][30] Their visual acuity may rival some eagles from the Aquila genus and some of the larger falcons as the greatest of any diurnal raptors.[31][32] The talons of martial eagles are impressive and can approach the size, especially in mature females, of those of the crowned eagle despite their slenderer metatarsus and toes compared to the crowned species.[33] Accipitrids usually kill their prey with an elongated, sharp hind toe-claw, which is referred to as the hallux-claw and is reliably the largest talon in members of the accipitrid family.[34] The average length of the hallux-claw in unsexed martial eagles from Tsavo East National Park, Kenya was found to be 51.1 mm (2.01 in).[28] In comparison, the average hallux-claw of a large sample of golden eagles was similar at 51.7 mm (2.04 in). Meanwhile the three largest clawed modern eagles were found to measure as such: in small samples, the Philippine eagle and crowned eagle had an average hallux-claw length of 55.7 mm (2.19 in) and 55.8 mm (2.20 in), respectively, and harpy eagles have an average hallux-claw length of approximately 63.3 mm (2.49 in).[35][36][37][38] The inner-claw on the front of the foot of the martial eagle is especially sizeable proportional to other extremities and unusually can approach, if not reach, the same size as the hallux-claw. This inner-claw was found to average 46.1 mm (1.81 in), in comparison to that of the crowned eagle which measures 47.4 mm (1.87 in).[28][39] The tarsus is quite long in martial eagles, the fourth longest of any living eagle and the longest of any booted eagle species, seemingly an adaptation to prey capture in long grass, including potentially dangerous prey.[2][11] The bill is of medium-size relative to other large eagles, with a mean culmen length from Tsavo East of 43.7 mm (1.72 in). Their bill is larger than the average bill size of the large members of the Aquila genus but is notably smaller than those of the large species of sea eagle and the Philippine eagle.[28][24][37][35][40] The gape size of martial eagles is relatively large however, being proportionally larger than in other booted eagle species behind (albeit considerably behind) the Indian spotted eagle (Clanga hastata) in relative gape size, indicating a relative specialization towards swallowing large prey whole.[41]

Voice

The martial eagle is a weak and infrequent vocalizer. Little vocal activity has been reported even during the breeding season. The recorded contact call between pair-members consists of the birds, usually when perched, letting out a low mellow whistle, ko-wee-oh. More or less the same vocalization is known to have been uttered by females when male brings food and repeated mildly by large begging young. During territorial aerial display and sometimes when perched, adults may utter a loud, trilling klee-klee-klooeee-klooeee-kulee. The territorial call may be heard from some distance. Recent fledglings also at times make this call. A soft quolp may be heard, made by pairs around their nest, perhaps being a mutual contact call.[2][3][9] In comparison, the crowned eagle is highly vocal especially in the context of breeding.[9]

Habitat

The martial eagle is to some degree adaptable to varied habitats but shows an overall preference for open woods and woodland edges, wooded savannah and thornbush habitats. The martial eagle has been recorded at elevations of up to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) but is not a true mountain dwelling species and resident eagles do not usually exceed an elevation of 1,500 m (4,900 ft).[2][3] These eagles also avoid closed-canopy forests and hyper-arid desert.[7] As such it is mostly absent from Guinean and Congolian forests, despite the species’ requirement for large trees for nesting purposes. It is shown that martial eagles can inhabit forests locally in areas where openings occur.[9] For example, in a bird atlas for the country of Kenya, perhaps surprisingly, 88% of martial eagles were found to reside in well-wooded areas and they occurred in areas where annual rainfall exceeded 250 mm (9.8 in).[42] In southern Africa, they have adapted to seemingly more open habitats than elsewhere in their range, such as semi-desert and open savanna with scattered trees, wooded hillocks and, as a recent adaptation, around pylons. In the desert areas of Namibia, they utilize ephemeral rivers that flow occasionally and allow large trees to grow.[2][7] They usually seem to prefer desolate or protected areas. In the Karoo of South Africa, they consistently avoid areas with moderate to heavy cultivation or with heavier or more consistent winter rainfall.[43] One study on the occurrence of diurnal raptors in protected areas versus outside unprotected areas, found that martial eagle detection was nearly twice as frequent in protected areas during the dry season and more than three times as frequent during the wet season. Some assorted diurnal raptors were even relatively rarer outside of protected areas such as hooded vultures (Necrosyrtes monachus).[44]

Behavior

The martial eagle spends an exceptional amount of the time in the air, often soaring about hill slopes high enough that binoculars are often needed to perceive them. When not breeding, both mature eagles from a breeding pair may be found roosting on their own in some prominent tree up to several miles from their nesting haunt, probably hunting for several days in one area, until viable prey resources are exhausted, and then moving on to another area.[9][45] However, martial eagles, especially adult birds, are typically devoted to less disturbed areas, both due to these typically offering more extensive prey selection and their apparent dislike for a considerable human presence.[43] Martial eagles tend to be very solitary and are not known to tolerate others of the own species in the area outside of the pair during the breeding season.[46] In general this species is shier towards humans than other big eagles of Africa, but may be seen passing over populated country at times.[9] The most frequently seen type of martial eagle away from traditional habitats are presumed nomadic subadults. One individual that was ringed as subadult was recovered 5.5 years later 130 km (81 mi) away from the initial banding site. Another martial eagle ringed as a nestling was found to have moved 180 km (110 mi) in 11 months.[2]

Dietary biology

The martial eagle is one of the world's most powerful avian predators. Due to both its underside spotting and ferocious efficiency as a predator it is sometimes nicknamed “the leopard of the air”.[47] The martial eagle is an apex predator, being at the top of the avian food chain in its environment.[25] In its common, scientific and most regional African names, this species name means “war-like” and indicates the force, brashness and indefatigable nature of their hunting habits. The aggressiveness of the hunting martial eagle, which may rival that of the overall behaviorally bolder crowned eagle, can seem incongruous with their other behaviours, as it otherwise is considered a shy, wary and evasive bird.[3][48][49] Martial eagles have been seen to charge at much larger adult ungulates and rake at their heads and flanks, at times presumably to separate the mammals from their young so they can take the latter with more ease.[50][51] At other times, these eagles will set down upon a wide-range of potentially dangerous prey including other aggressive predators in broad daylight, such as monitor lizards, venomous snakes, jackals and medium-sized wild cats.[3] Adult eagles tend to hunt larger, potentially dangerous prey more often than immature ones, presumably as they refine their hunting skills with maturity.[3] The martial eagle hunts mostly in flight, circling at a great height anywhere in its home range. When prey is perceived with their superb vision, the hunting eagle then stoops sharply to catch its prey by surprise with the prey often being unable to perceive the eagle at nearly as far as the eagle can perceive them despite often being in the open.[2][9] The martial eagle tends to hunt in a long, shallow stoop, however when the quarry is seen in a more enclosed space, it parachutes down at a relatively steeper angle. The speed of descent is controlled by the angle at which the wings are held above the back. At the point of impact, it shoots its long legs forward, often killing victims on impact somewhat like large falcons often dispatch their prey.[3][9] Prey may often be spotted from 3 to 5 km (1.9 to 3.1 mi) away with a record of about 6 km (3.7 mi).[2] On occasion, they may still-hunt from a high perch or concealed in vegetation near watering holes. If the initial attempt fails, they may swoop around to attempt again, especially if the intended victim is not dangerous. If the quarry is potentially hazardous, such as mammalian carnivores, venomous snakes or large ungulates, and becomes aware of the eagle too soon, the hunt tends to be abandoned.[2][3] Unusually for a bird of its size, it may rarely hover while hunting. This hunting method may be employed particularly if the quarry is any of the aforementioned potentially dangerous prey items such as venomous snakes or carnivores. Other large eagles may hunt similarly (if infrequently) hover over prey such as canids and then quickly drop onto if the quarry makes the mistake of pointing its dangerous mouth downwards, then gripping its victim on the back while controlling the neck with the other foot until blood-loss is sufficient to cause the prey to expire.[52][23] Prey, including birds, are generally killed on the ground, with infrequent reports of prey taken from trees. Some larger (and presumably slower-flying) avian prey may be taken while in flight, victims of successful hunts as such have consisted of water birds such as herons, storks and geese.[3] If kills are too large and heavy to carry in flight, both members of a pair may return to the kill over several days, probably roosting nearby. If nesting, the pair tends to dismember pieces of large kills such as limbs to bring to the nest. Much of the large prey, perhaps most, that is left on the ground is lost to scavengers, however.[2][3]

The diet of the martial eagle varies greatly with prey availability and can be dictated largely by opportunity. Remarkably, mammals, birds and reptiles can in turn dominate the prey selection of martial eagles in a given area with no one prey type globally dominating their prey spectrum.[3][9] In some areas, both mammals and birds can each comprise more than 80% of the prey selection.[9][53] Over 160 prey species have been reported for the martial eagle which is a much higher number than the full prey spectrum of other larger African booted eagles, and even this may neglect some of the prey they take in the little studied populations from west and Central Africa and the northern part of east Africa.[3][54] Prey may vary considerably in size but for the most part, prey weighing less than 0.5 kg (1.1 lb) are ignored by hunting martial eagles, with only about 15% of the known prey species averaging less than this. A majority of studies report the average size of prey for martial eagles being between 1 and 5 kg (2.2 and 11.0 lb).[3][55] Average weight of prey taken as been reported at as low as 1.2 kg (2.6 lb).[56] However, the mean prey body mass is considerably higher in known dietary studies. In by far the largest dietary study thus far conducted for the martial eagle species (in the Cape Province, South Africa) the estimated mean prey body mass was approximately 2.26 kg (5.0 lb).[55] In Tsavo East National Park of Kenya, the mean estimated body mass of prey was quite similar at approximately 2.31 kg (5.1 lb).[28] Despite perhaps a majority of prey for this species weighing less than 5 kg (11 lb), martial eagles regular prey size range is claimed at up to 12 to 15 kg (26 to 33 lb).[5][57][58] There is some evidence of prey partitioning (which can be potentially delineated both by prey species and body size of prey items taken) between the sexes. This is typical of raptors with pronounced size sexual dimorphism, as is the case in martial eagles. For instance, in populations where large adult monitor lizards are significant as prey, they only start to appear in prey remains at nests only after the female resumes hunting in the latter part of the breeding season.[3]

Mammals

The most diverse class of prey in the diet as known are mammals, with over 90 mammalian prey species reported.[3] In the Cape Province, the 2.1 kg (4.6 lb) cape hare (Lepus capensis) reportedly dominates the prey selection, comprising about 53% of the foods selected.[55] Other lagomorphs, namely the slightly smaller Smith's red rock hare (Pronolagus rupestris), mildly larger African savanna hare (Lepus microtis) and the much larger 3.6 kg (7.9 lb) scrub hare (Lepus saxatilis), are not infrequently taken both in and outside of the Cape area, but lagomorphs are not typically the main prey elsewhere.[3][55][59] For the most part rodents are ignored as prey as they are probably too small despite martial eagles taking at times appreciable numbers of Cape (Xerus inauris) and unstriped ground squirrels (Xerus rutilus).[55][60][61] However, rodents selected as prey have ranged in size from the 0.14 kg (4.9 oz) Southern African vlei rat (Otomys irroratus) to the 3.04 kg (6.7 lb) South African springhare (Pedetes capensis) and the 4 kg (8.8 lb) greater cane rat (Thryonomys swinderianus).[3][62][63] There are records of predation on 0.28 kg (9.9 oz) (the second largest African bat) straw-coloured fruit bats (Eidolon helvum) and galagos of various sizes (usually weighing a kilo or less) but otherwise mammalian prey they pursue tends to be relatively larger.[64][65][66]

Locally, large numbers are taken of any species of hyrax. The attractiveness of hyraxes as a prey resource may encourage martial eagles to vary their hunting techniques to potentially more time-consuming perch hunting so that they may capture rock hyraxes from rock formations and tree hyraxes from trees, contrary to their usual preference for capturing prey on the ground in the open after soaring high. Ranging in average mass from 2.2 to 3.14 kg (4.9 to 6.9 lb), hyraxes can comprise a healthy meal for a family of martial eagle and are probably among the larger items that male eagles will regularly deliver to nests.[55][67][68][69] Another miscellaneous mammal known to fall prey to martial eagles is the ground pangolin (Smutsia temminckii), although it is not clear the age pangolins that are preyed on and how they are dispatched, considering that adults weigh some 11.6 kg (26 lb) and have a hard keratin shell that is capable of withstanding lion (Panthera leo) jaws when in its rolled-up defensive posture.[3][4][70] Although far less accomplished and prolific as a predator of monkeys than the crowned eagle, the martial eagle has been known to prey on at least 14 species of monkey. The monkeys to turn up most often as martial eagle prey are grivets (Chlorocebus aethiops), vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) and malbroucks (Chlorocebus cynosuros), with mean body masses of 2.8 kg (6.2 lb), 4.12 kg (9.1 lb) and 4.53 kg (10.0 lb), respectively, because of their savanna-woods dwelling habits, tendencies to forage on the ground and their primarily diurnal activity.[3][28][68][71] Similarly, the larger Patas monkey (Erythrocebus patas), at 8.13 kg (17.9 lb), also dwells in similar habitats and so may be subject to occasional predaceous attacks.[72][73][74] There’s evidence that these monkey species have specific alarm calls, distinct from those uttered in response to the presence of a leopard (Panthera pardus) for example, specifically for martial eagles.[75][76] Martial eagles are also known to prey on mangabeys, Cercopithecus sp., colobus monkeys and guerezas, presumably around forest clearings, but these are probably quantitatively rare as prey given their forest-dwelling habits.[68][77][78][79] Predatory attacks by martial eagles have been reported as well for every species of baboon, although either mostly or entirely on young ones, and even on young chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes).[4][55][68][80][81] It has been claimed that juvenile monkeys are the most often selected as prey by martial eagles, even for species as small as vervet monkeys but little comprehensive analysis is known on this (the most accomplished primate predator, the crowned eagle, in Uganda, selects adult monkeys 52% of the time, juveniles 48% of the time).[56][82] On the hand, at times, martial eagles may at times be able to dispatch adult male monkeys weighing 9 kg (20 lb) or more, such as patas monkeys and Tana River mangabeys (Cercocebus galeritus), in seldom cases.[68][72]

Carnivores are exceptionally important prey for martial eagles. Among these many mongoose tend to be well represented in their diet. Most mongoose native to savanna tend to be highly social burrowers. Most of these types of mongoose are also relatively small (probably the second smallest important martial eagle food source after korhaans) and can effectively escape quickly to the safety of their underground home, so the lighter, more nimble male martial eagle is more likely to habitually pursue them. In southern Africa, the 0.72 kg (1.6 lb) meerkat (Suricata suricatta) comprises up to at least 9.6% of prey remains (as in the Cape Province) and the 0.75 kg (1.7 lb) Cape grey mongoose (Galerella pulverulenta) comprising an average of 7.2% of prey remains in the Cape area.[55][83][84] The largest of the social savanna-dwelling mongoose is the banded mongoose at 2.12 kg (4.7 lb). Despite often being successful in capturing banded mongoose, in one case when a (presumably inexperienced) immature martial eagle took one to a tree, the dominant male banded mongoose of the group scaled the tree and pulled away from the eagle the still-living mongoose prey to safety.[85][86] The martial eagle is a known predator of the full size range of mongoose species, from the smallest species, the 0.27 kg (9.5 oz) common dwarf mongoose (Helogale parvula), to the largest, the 3.38 kg (7.5 lb) white-tailed mongoose (Ichneumia albicauda).[68][87] Other moderate-sized carnivores known to fall prey to martial eagles include 0.83 kg (1.8 lb) striped polecat (Ictonyx striatus) and a few species of genet, which are about twice as heavy on average as the polecat.[4][55][68] The martial eagle, however, can be a surprisingly effective predator of carnivorans close to their own size or larger. In the Cape Province, 72 bat-eared foxes (Otocyon megalotis), which average about 4.1 kg (9.0 lb), were found in the prey remains, 85% of which were adults.[55][68] Other foxes have also been hunted, as well as both black-backed (Canis mesomelas) and golden jackals (Canis aureus).[55][88] Some of the black-backed jackals that martial eagles have captured and flown off with have included “half-grown” individuals and a rare adult, averaging some 8.9 kg (20 lb), may also be killed but is usually grounded prey. Despite being marginally the smallest of the 3 jackals, the black-backed is the most aggressive and predatory species, so are probably taken only in surprise blitzes.[55][68][89] Adult domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) of up to a modest size may occasionally be killed by martial eagles.[90] Martial eagles are also known to opportunistically grab pups of African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) as they emerge from their dens.[91] A similarly impressive range of felids have been included in their prey spectrum. Adults of both domestic cats and their ancestors, the 4.65 kg (10.3 lb) African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), are known to fall prey to this species.[55][90] Arguably their most impressive mammalian carnivore prey though are adults of much larger cat species such as the 10.1 kg (22 lb) serval (Leptailurus serval) and even the 12.7 kg (28 lb) caracal (Caracal caracal).[3][55][68] Apparent predatory attacks are even attempted on big cat cubs as they are considered potential predators of lion and leopard (Panthera pardus) cubs and confirmed predators of cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) cubs. Evidence shows, however, they rapidly abandon hunting attempts if the formidable mother lion or leopard are present.[92][93][94][95] Successful predatory attacks on other relatively large carnivores have included adults of the 12.4 kg (27 lb) African civet (Civettictis civetta) and the 8.16 kg (18.0 lb) aardwolf (Proteles cristata).[55][96]

While large accipitrids from around the world are credited with attacks on (almost always young) ungulates, perhaps no other species is as accomplished in this regard as this martial eagle. Over 30 species of ungulate have been identified as prey for this species, more species than are attributed to the perhaps more powerful crowned eagles and all the world’s golden eagles, although in all 3 seldom more than 30% of the diet are comprised by ungulates in a given region.[3][28][23][55] In Kruger National Park, the martial eagle is mentioned as the only bird considered as a major predator of ungulate species.[97] A majority of the ungulate diet of martial eagles are comprised by small antelope species or the young of larger antelopes. Locally favored prey are the dik-diks, one of the smallest kind of antelope, and every known species may be vulnerable to this eagle.[98] In Tsavo East National Park, Kirk's dik-dik (Madoqua kirkii) were the second most numerous prey species and it was estimated that at least 86 dik-diks are taken in the park over the course of the year by two pairs of martial eagles. At an average of 5 kg (11 lb), these can provide a very fulfilling meal for an eagle family.[28] Adults of other smaller antelope such as 4.95 kg (10.9 lb) suni (Neotragus moschatus) and 4.93 kg (10.9 lb) blue duikers (Philantomba monticola) are probably also taken with relative ease.[3][55][68] In general, the young of other antelope are usually attacked, including newborns. Occasional ambush attacks or successful predations are reported on adults of much larger species despite young ones being rather more vulnerable, including 12.1 kg (27 lb) klipspringers (Oreotragus oreotragus), 11.1 kg (24 lb) steenboks (Raphicerus campestris), both species of grysbok (7.6 to 10.6 kg (17 to 23 lb) on average), 14.6 kg (32 lb) oribis (Ourebia ourebi) and perhaps up to half a dozen larger duikers, potentially weighing from 7.7 to 25 kg (17 to 55 lb).[3][55][97][98][99][100][101] One duiker dispatched via strangulation weighed an estimated 37 kg (82 lb), the largest known raptorial kill for any species on the African continent.[2][3][102] Among extant birds of prey, only wedge-tailed eagles, reportedly capable of killing sheep and female red kangaroos (Macropus rufus) weighing up to 50 kg (110 lb), and golden eagles, credited with taking adult female deer of several species with weights estimated at 50 to 70 kg (110 to 150 lb) and capable of apparently dispatching domestic calves weighing up to 114 kg (251 lb), have larger kills attributed to them.[103][104][105][106] Calves, including neonatal young, of the following antelope may also be included in their prey spectrum: impala (Aepyceros melampus), hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus), bontebok (Damaliscus pygargus), common tsessebe (Damaliscus lunatus), springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), Eudorcas gazelles, gerenuk (Litocranius walleri), bushbuck (Tragelaphus sylvaticus), grey rhebok (Pelea capreolus), kob (Kobus kob) and mountain reedbuck (Redunca arundinum). These species can vary in weight from 2.6 kg (5.7 lb) (i.e. gazelles) to 11 kg (24 lb) (i.e. tsessebe) in newborns.[3][28][55][107][108][109][110][111] For the newborn impala, weighing already 5.55 kg (12.2 lb), the martial eagle is the only bird considered to be a significant predator.[57][112] Additionally, piglets of warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus) (of which only the martial eagle among accipitrids is similarly mentioned as a significant predator) and bushpigs (Potamochoerus larvatus) are taken.[4][55][113]

Birds

Compared to the range and sizes of mammals included in their prey spectrum, birds taken by martial eagles may seem less impressive as a whole but the morphology of the martial eagle, including large wing surface areas, pronounced sexual dimorphism and relatively long toes, shows the species’ partial adaptation to capture of avian prey. Birds are universally considered by biologists more difficult to capture than mammals of the same size. In all, more than 50 bird species have been identified as the prey of martial eagles.[2][3][114] The most significant portion of the avian diet is comprised by medium-sized terrestrial upland birds such as guineafowl, spurfowl and bustards. In total more than a dozen species of the galliform order and the bustard family each have been identified as their prey.[3][4][55] When attacking these ground-loving birds, which are understandably quite easily spooked and usually react to potential danger by flying off, martial eagles almost always try to take them on the ground much like they do mammalian prey. If the birds take flight, the hunting attempt will fail, although a hunting eagle may try to surprise the same birds again.[3] In Niger, the most numerous prey species is apparently the 1.29 kg (2.8 lb) helmeted guineafowl (Numida meleagris).[115] Other guineafowl such as the vulturine (Acryllium vulturinum) and crested guineafowl (Guttera edouardi) are also readily taken elsewhere.[116][117] Guineafowl and spurfowl were stated as the most numerous prey for martial eagles in Kruger National Park.[118] In Tsavo East National Park, the 0.67 kg (1.5 lb) red-crested korhaan (Lophotis ruficrista), perhaps the smallest bustard the eagle hunts, is the most numerous prey taken, comprising about 39% of the prey remains.[28] Medium sized bustards such as the 1.2 kg (2.6 lb) Hartlaub's bustard (Lissotis hartlaubii) and the 1.7 kg (3.7 lb) Karoo korhaan (Eupodotis vigorsii) were oft-taken supplemental prey in Tsavo East and the Cape Province, respectively.[28][22][55] Although these are not usually taken in large numbers, martial eagles are one of the main predators of larger bustards. These may include (averaged between the extremely size dimorphic sexes) the 3.44 kg (7.6 lb) Ludwig's bustard (Neotis ludwigii), the 5.07 kg (11.2 lb) Denham's bustard (Neotis denhami) and even the Kori bustard (Ardeotis kori), seemingly the heaviest bustard in the world on average at 8.43 kg (18.6 lb).[4][22][55] Attacks on adult male Kori bustards, which are certain to be the largest avian prey attacked by martial eagles and are twice as heavy as females, averaging some 11.1 kg (24 lb), can be extremely prolonged. One protracted battle resulted in an injured leg for the eagle and massive, fatal blood loss for the male bustard, which was ultimately scavenged by a jackal by the following morning.[22][119]

Despite its preference for ground-dwelling avian prey, a surprisingly considerable number of water birds may also be attacked. Waterfowl known to be attacked include the 1.18 kg (2.6 lb) South African shelduck (Tadorna cana), 1 kg (2.2 lb) yellow-billed duck (Anas undulata), the 4.43 kg (9.8 lb) spur-winged goose (Plectropterus gambensis) (Africa’s largest waterfowl species) and especially the peculiar, overly bold and aggressive 1.76 kg (3.9 lb) Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca), which is one of the main prey species for martial eagles in Kruger National Park.[3][4][22][55][118][120] Larger wading birds are also fairly frequently attacked including herons and egrets, flamingoes storks, ibises, spoonbills and cranes.[3][4][55][121][122] The diversity and number of storks taken is particularly impressive. They are known to take 8 species of stork, ranging from the smallest known species, the 1.08 kg (2.4 lb) African openbill (Anastomus lamelligerus), to the tallest species in the world, the 6.16 kg (13.6 lb), 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in)-tall saddle-billed stork (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis). One naturalists observed up to a half dozen attacks in different parts of Africa on 3.45 kg (7.6 lb) white storks (Ciconia ciconia).[3][123][124] Short of three attacks on spotted thick-knees (Burhinus capensis), which weigh about 0.42 kg (15 oz), so far as is known small waders or shorebirds are ignored as prey.[3][55] Other assorted avian prey may consists of ostrich (Struthio camelus) chicks (frequently resulting in the immediate ire of protective ostrich parents), sandgrouse, pigeons and doves, hornbills and crows.[3][4][55] Beyond occasional captures of other birds of prey (covered later), one other impressive avian prey species is the southern ground hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri), which at 3.77 kg (8.3 lb) is probably the world’s largest hornbill.[22][125] At the other end of the scale, some martial eagles may capture a few small social species of passerine, which are exceptionally small prey (the smallest recorded prey species for the eagle overall), potentially consisting of the 18.6 g (0.66 oz) red-billed queleas (Quelea quelea) and the 27.4 g (0.97 oz) sociable weavers (Philetairus socius), as practically every meat-eating bird in Africa may be attracted to these species’ colonial abundance.[3][22][126]

Reptiles

_with_its_prey_-_a_White-throated_Monitor_Lizard_(16844993595).jpg)

Reptiles can be locally important in the diet, and they are known to take larger numbers of reptiles than other large African booted eagles. Only relatively large reptiles, it seems, are attacked and many of this prey is also potentially dangerous, so a great majority time such prey is taken in ambushes.[3][11] In particular, in the former Transvaal province of northeastern South Africa, reptiles were the main prey, with monitor lizards alone comprising just under half of the prey remains. The monitors attacked may include the 6.1 kg (13 lb) rock monitor (Varanus albigularis), the 5.25 kg (11.6 lb) nile monitor (Varanus niloticus) and the 1.02 kg (2.2 lb) savannah monitor (Varanus exanthematicus). These monitors, the largest lizards in Africa, are formidable prey and almost all attacks are ambushes on adult monitors by mature female eagles. Sometimes a lengthy struggle will ensue as the eagles try to get a good grip into the tough back skin of the monitors while simultaneously trying to control their necks to avoid the prey’s powerful jaws, however the eagles are usually successful in dispatching the large lizards.[3][4][28][55][127][128][129][130] Reptiles as a whole made up 38% of the prey remains from Kruger National Park. These consisted of monitor lizards as well as wide range of venomous snakes, including Cape cobras (Naja nivea), boomslangs (Dispholidus typus), puff adders (Bitis arietans), the eastern (Dendroaspis angusticeps) and western green mambas (Dendroaspis viridis), and even black mambas (Dendroaspis polylepis), these species ranging in size from the 0.3 kg (11 oz) boomslang to the 1.6 kg (3.5 lb) black mamba. Also taken here were the non-venomous but already sizeable youngsters of the African rock python (Python sebae), the largest African snake.[118][131] Elsewhere, snouted cobras (Naja annulifera) may added to the list of their prey spectrum.[4] A surprising number of tortoises and turtles are also taken by martial eagles, ranging from one of the smallest tortoises, the 0.23 kg (0.51 lb) greater padloper (Homopus femoralis) to the one of the largest, the 10.8 kg (24 lb) leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis) (though probably only small specimens of the latter species are taken of this, the second largest tortoise on mainland Africa).[55][132][133][134][135][136] In one case, an estimated 90 cm (2 ft 11 in) nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) was captured and flown with by a martial eagle.[137]

Interspecies predatory relationships

.jpg)

For terrestrial predators, including birds of prey, sub-Saharan Africa may be the most competitive environment in the modern world. Due to great diversity of raptors present, each species have shown adaptive specializations, which may consist of various morphological differences that allow them to capitalize on distinct prey selection, hunting methods, habitat and/or nesting habits.[2][3][138][139] The larger booted eagles that dominate the avian food chain in Africa consists of martial eagles, 4 kg (8.8 lb) Verreaux's eagles and 3.64 kg (8.0 lb) crowned eagles, which due to their size and conspicuousness may lend themselves to comparisons. While prey species may overlap in these in southern Africa and some parts of east Africa, where the prey size range of all three eagles averages 1 to 5 kg (2.2 to 11.0 lb), these three powerful eagles differ considerably in habitat preferences, nesting habits and hunting methods. The Verreaux's eagle nests in and hunts around rocky, mountainous kopje to be in close proximity to the much favored prey, rock hyraxes, which they mainly use contour-hunting (hugging the uneven ground to surprise the prey) to capture. The crowned eagle dwells mainly in mature forests, building nests in large interior trees, and is primarily a perch-hunter, watching and listening for monkeys and other prey over a long period. While all three are known to locally favor rock hyraxes, the nesting habitat differences where they overlap are sufficient to allow these birds not to effect one another.[2][3][15][20][22][140] The average prey mass of Verreaux's eagle was similar to that martial eagles, with a pair of studies showing it ranges from 1.82 to 2.6 kg (4.0 to 5.7 lb).[23][141] The mean prey mass of crowned eagles in southern Africa also appears to be similar to that of martial eagles but in west Africa (i.e. Ivory Coast) it was considerably heavier at 5.67 kg (12.5 lb) (which may well be the highest mean prey mass for any of the world’s raptors).[127][142] Elsewhere, mean prey masses for the larger booted eagles appears to be considerably smaller than in the larger African species, i.e. single studies for the Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti) and wedge-tailed eagles showed means of 0.45 kg (0.99 lb) and 1.3 kg (2.9 lb), respectively, while a large number of extensive dietary studies for the golden eagle show its global mean prey mass is around 1.61 kg (3.5 lb).[23][143][144]

More similar in habitat and, locally, prey selection to martial eagles are three medium-sized eagles, the 1.47 kg (3.2 lb) African hawk-eagle (Aquila spilogaster), the 2.25 kg (5.0 lb) tawny eagle (Aquila rapax) and the 2.2 kg (4.9 lb) bateleur (Terathopius ecaudatus).[3][28][22] The biology of martial eagles was compared extensively with that of these species in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya, where all four were known to prey on large numbers of Kirk's dik-diks (albeit none of these took as many as did the martial eagles and some eaten by bateleurs and tawny eagles are probably scavenged). It was found that the bateleur and tawny eagle are even broader in their prey composition and take live prey more often of a smaller size, also often coming to and feeding on carrion (which is seldom seen in martial eagles) and pirating from other raptors, especially the tawny eagles. The African hawk-eagle takes fairly similar prey to the martial eagle but does not conflict with martial eagles considering its much smaller size and preference for slightly denser wooded areas. In Tsavo East, 29% of prey of tawny eagle and 21% of bateleur foods were the same that of martial eagles. In east Africa, the breeding season differs mildly between these eagles with bateleurs nesting much earlier than the others and African hawk-eagles breeding peaking slightly later. Thus pressure on shared prey types such as dik-diks are exerted at different times of the year. While the bateleur and tawny eagle can kill prey weighing up to 4 kg (8.8 lb) and the African hawk-eagle (being relatively large footed and clawed despite its smaller size) can kill prey of up to 5 kg (11 lb), these raptors are too small to regularly go after live prey as large in the prey spectrum of martial eagles, with the bateleur and tawny having talons relatively smaller even adjusted for their body size (the hawk-eagle’s talons were relatively similar in proportion to their body size).[2][3][28] Due to its large size and broad wings, martial eagles are not highly maneuverable in flight and are not infrequently robbed of their catches by these more agile and swift smaller eagles, particularly bold tawny eagles. Other raptors to steal food from martial eagles include bateleurs and even other big species such as Verreaux's eagles and lappet-faced vultures (Torgos tracheliotos). Considering their potential for aggressiveness in regards to prey pursuits, martial eagles can be surprisingly passive in response to kleptoparasitism, especially if they are able to first fill their crop. This may be because they try to avoid unnecessary expenditures of energy in contention over food.[3][145] Leopards also rarely steal kills from martial eagles but may also be robbed of small kills by martial eagles as have cheetahs.[146][147] In another case, a martial eagle stole a rock hyrax from a bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus).[3] Prey species are shared by a wide range of birds of prey, both other eagles and other, usually, larger raptors, and mammalian carnivores of many sizes that are too numerous to mention. Some mammalian carnivores such as caracals have superficially similar diets to martial eagles.[148][149] One other species worth noting is the Verreaux's eagle owl (Bubo lacteus), as it is similarly the largest African owl, weighing about 2.1 kg (4.6 lb), with almost identical habitat preferences and distributional range as the martial eagle.[3][22][24] Therefore, some consider the eagle owl to be the martial eagle’s nocturnal ecological equivalent.[150] While there is considerable overlap in their diets, there are discrepancies as the eagle owl tends to hunt large numbers of hedgehogs (not known in the eagle’s diet) and occasionally high quantities of mole-rats. When considered this in combination with their different times of activity and the fact that the eagle owl weighs about half as much as the martial eagle, direct competition probably does not affect either predator in any considerable way.[3][151]

The martial eagle infrequently hunts other birds of prey, perhaps doing so only slightly more often than do crowned eagles and Verreaux's eagles.[3][55] In comparison, the temperate-zone-dwelling golden eagle is a fairly prolific predator of other birds of prey. This may be due to more scarce prey resources in colder regions forcing eagles to pursue difficult prey such as this more frequently, whereas booted eagles in rich Africa biospheres may not need to do so as much.[23][152][153] Nonetheless, a somewhat diverse range of raptorial birds have been identified as prey for martial eagles: the 0.61 kg (1.3 lb) lanner falcon (Falco biarmicus), the 0.65 kg (1.4 lb) spotted eagle owl (Bubo africanus) (with a surprisingly large number of 6 found at one nest in Tsavo East), the 0.67 kg (1.5 lb) pale chanting goshawk (Melierax canorus), the 2.04 kg (4.5 lb) hooded vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus) (in one case after a protracted aerial battle), the 4.17 kg (9.2 lb) white-headed vulture (Trigonoceps occipitalis) and even Africa’s largest bird of prey, the 9.28 kg (20.5 lb) Cape vulture (Gyps coprotheres).[28][15][55][154][155][156] As apex predators, martial eagles are themselves largely invulnerable to predation. A video exists that purportedly depicts a leopard killing a martial eagle but this eagle was misidentified as it actually features a leopard preying on an immature African fish eagle (Haliaeetus vociferus) (and, at that, one that was possibly grounded for unknown reasons).[157] There are, however, verified (if rare) cases of caracals preying on sleeping martial eagles at night, by climbing trees and pouncing in an ambush.[158][159] It is possible that leopards may too ambush sleeping eagles but post-fledgling martial eagles are known to be highly wary and healthy individuals a great majority of the time will successfully evade potential dangers by day.[3] Predation on nests of martial eagles, beyond those by humans, are little-known, with no verified depredations known in the literature, but are likely to occur.[160]

Territiorality

Despite their rather aerial existence, the territorial display of adult martial eagles is considered relatively unspectacular. Their display often consists of nothing more than the adult male or both members of a pair circling and calling over their home range area or perching and calling near nestlings. Compared to other large African booted eagles, this species infrequently “sky-dances” (i.e. undulation and dramatic movements high in the sky), but some are known with presumably the male martial eagle only engaging in shallow undulations.[2][9][161] During mutual circling, the adult female may turn and present talons. Martial eagles are not known to “cartwheel” which is when two eagles lock feet and circle down, falling almost to the ground, an action that was once thought to be part of breeding displays but is known generally considered territorial in nature.[2][162] The territory of martial eagles can vary greatly in size. The average home range is estimated to be 125 to 150 km2 (48 to 58 sq mi) in east Africa and southern Africa, with mean distances between nests of approximately 11 to 12 km (6.8 to 7.5 mi).[2] In Kruger National Park, the average home range of pairs is 144 km2 (56 sq mi) with an average nest-spacing of 11.2 km (7.0 mi). In Namib-Naukluft National Park, Namibia, the home range size was 250 km2 (97 sq mi) per pair.[3] Within Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa, nest spacing ranged from 15.1 km (9.4 mi) in the Auob river basin to 31.3 km (19.4 mi) in the interior dunes area.[160] In the Nyika Plateau of northern Malawi, the average nest spacing was 32 km (20 mi), with only one martial eagle nest recorded in an area that contained four crowned eagle nests.[163] In protected areas of west Africa, the average home range size of martial eagles is about 150 to 300 km2 (58 to 116 sq mi).[164] Somewhat surprisingly, considering their relative scarcity in west Africa overall in comparison in east and southern Africa, home ranges may be just as large in some parts of Kenya, at up to 300 km2 (120 sq mi), and the largest known home ranges sizes known come from southern Africa. These are from Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park where the home ranges may be anywhere from 225 to 990 km2 (87 to 382 sq mi), with average spacing between nests of 37 km (23 mi). By the 1990s, approximately 100 pairs were estimated to breed in Hwange.[2][165] This disparity in territory sizes are likely due to regional differences in food supply, persecution rates and habitat disturbance.[2][8]

Breeding

Martial eagles may breed in various months in the different parts of their range. They are considered a fairly early breeder compared to the average for sub-Saharan Africa birds of prey but breed much less early than bateleurs.[28][166][167] The mating season is in November through April in Senegal, January to June in Sudan, August to July in northeast Africa and almost any month in east Africa and southern Africa, though mostly in April–November. The breeding season may thus begin in various parts of the range in a wet season or the earlier or later part of the local dry season so that no part of the brooding stage will occur during heavy rains.[2][9] They build their nests in large trees, often larger than other trees in the woodlot. The nest is usually placed them in the main fork of tree at 6–20 m (20–66 ft) off the ground, though nests have been recorded at anywhere from 5 to 70 m (16 to 230 ft) high, in the highest cases on top of the tree canopy. Tree species is unimportant with the eagles seeming to prefer any type that it difficult to climb, such as those that have thorny branches, few lower branches or smoother bark.[2][9][100] In Kalahari Gemsbok National Park of South Africa, almost all nests were in the highly thorny, Acacia-like tree, Vachellia erioloba, in savanna areas.[160] Most nests in southern Africa often are at a height of less than 15 m (49 ft).[3] Often trees used are on the sides of cliffs, ridges, valley or hilltop, with one nest having been found within a cave.[2][168] In the karoo of South Africa, they have also nested on electric-power pylons. Locally, with the sometimes epidemic levels of clear-cutting of old-growth trees, such pylons may provide a fairly suitable alternative that the eagles can utilize in absence of woodlands.[169][170][171] The nest of the martial eagle is a large and conspicuous construction of sticks. In the first year of construction, the nest will average 1.2 to 1.5 m (3.9 to 4.9 ft) in diameter and measure about 0.6 m (2.0 ft) deep. After regular use over several years, the nests can regularly measure in excess of 2 m (6.6 ft) in both diameter and depth. The nest may be lightly lined with green leaves.[2] The central depression of the nest averages about 0.4 to 0.5 m (1.3 to 1.6 ft) across.[3] The nest of martial eagles average slightly smaller than those of crowned eagles and, compared to other large eagle tree nests, are much broader than they are deep, relatively, especially when newly constructed.[9] The construction of new nests can take several months and, in some cases, pairs can take up to two months where they appear to return to the nests daily but contribute only green leaves to line the nest. The repair of an existing nest takes on average two to three weeks. Most pairs will usually just use one nest (as opposed to temperate-zone eagles which may have several alternate nests), with up to 21 years of continuous use for one nest recorded, but pairs constructing a second nest are not infrequent either. One exceptionally prolific pair built or repaired 7 nests during 17 years in Zimbabwe, although they only nested 5 of the 17 years.[3][172]

Martial eagles have a slow breeding rate, laying usually one egg (rarely two) every two years. Clutches of two have only been reported only in South Africa and once in Zambia and the younger sibling probably never survives or possibly ever even hatches unless the first egg or hatchling dies.[9][173] Martial eagle eggs are rounded oval and are white to pale greenish-blue, variously. Sometimes they may be handsomely marked with brown and grey blotches. The eggs of martial eagles measure 79.9 mm × 63.4 mm (3.15 in × 2.50 in) on average among 57 eggs, with ranges of 72 to 87.5 mm (2.83 to 3.44 in) in egg length by 60 to 69 mm (2.4 to 2.7 in) in width. Their eggs are the largest of any booted eagle, slightly larger on average than those of golden or Verreaux's eagle and considerably larger than those of crowned eagles.[3][9][174][175] The egg is incubated for 45 to 53 days. The female does a great majority of the incubation, as is typical, but the male may relieve her and incubate for a maximum of three hours in a day.[2][3] If the nest is approached by humans, the female tends to sit tight, often only flying off once the nest is reached. Unlike the crowned eagle, the martial eagle is not known to protectively attack animals such as humans who come too close to the nest, usually just unobtrusively abandoning the nest until the person leaves the area, in a similar fashion to Aquila eagles. However, if maimed or grounded themselves, martial eagles are known to viscously turn on their human tormentors until they are finished off, in some anecdotal claims of early hunting journals, an occasion hunting accident have resulted in martial eagles tearing the flesh down to the bone on the legs of game wardens and even broken arms with their powerful grip. Although these accounts are quite possibly exaggerated, the ferocity of cornered martial eagles may have some influence on its name.[3][21][176][177] Once the eggs hatch, the male of a pair may rarely brood the young but has never been seen to the feed the chick and, for the most part, the male just brings prey for the female to distribute between herself and the nestling. The female attendance at the nest drops considerably at seven weeks after hatching, at which point she resumes hunting. Then, the female may become main food provider but males will also make deliveries. Despite her lower attendance, she still roosts on or near the nest until the nestling stage is done. Despite the occasional capture of food, the male usually is rarely seen near the nest after the female resumes hunting.[3][9] In one unusual case, a first or second year plumaged male martial eagle was seen assisting an adult female in the way that an adult male would but it was not known if he had merely replaced a deceased male that had sired the young or had actually bred with the female, the following year the young male was verified to mate with the female. Cases of immature plumaged eagles breeding are often considered indicative of stress on a species’ regional population.[3]

_juvenile_(13816501623).jpg)

The newly hatched chick tends to have a two-tone down pattern which is dark grey above and white below, which lightens at about four weeks of age, with the down becoming pale-grey. At 7 weeks, the feathers mostly cover the down and do so completely by 10 weeks except that at that stage the flight feathers are underdeveloped.[3] The new chick is usually quite weak and feeble, becoming more active only after they are 20 days old.[9] The nestlings usually first feeds itself at 9 to 11 weeks old, while it tends to engage in vigorous wing exercises performed from 10 weeks on. Like crowned eagles, males seem to be more active than female youngsters and probably fly sooner too. In one case, a male fledged prematurely at 75 days, however it is possible that male fledging can occur at less than 90 days.[3] Most estimations place fledging as occurring at 96 to 109 days, on average at about 99 days of age. However, after making their first flight, the fledgling usually return to roost in the nest for several days, before gradually moving away from it.[2][3][9] Despite increasing signs of independence (such as flight and beginning to practice hunting), in extreme cases, juvenile birds may remain in the care of their parents for a further 6 to 12 months. A typical post-fledgling care stage will continue for about 3 months after fledging. Despite its ability to fly, it will continue to beg for food from both parents as they are seen. Sometimes, the young eagle from the prior mating season may still be present at the onset of the next breeding season. Evidence exist of juvenile eagles returning to their nest site at as old as 3 years of age but are likely to be no longer fed.[3][9] On the other hand, juvenile martial eagle soar much more readily than crowned eagles and, unlike that species, have been recorded traveling up to several miles from the nest 3 to 4 months after making their first flight.[9] Due to this long dependence period, these eagles can usually only mate in alternate years.

Breeding success is variable and is probably driven by a combination of factors, including prey supply, rainfall levels and distance from human activity.[161][178] In Kenya in the 1960s, breeding success at producing a fledgling was 72% for all eggs and 48% for all possible attempts. Here, various pairs reared between 0.25 and 1 young per pair, averaging 0.55.[3][9][179] In the Namibian Nest Record Scheme, where young were monitored for more than two months, success has also been estimated at 83%, i.e. five out of six attempts.[180] At Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa, 38 of 53 martial eagle breeding attempts were in consecutive years and fledged an average 0.43 young per year.[160] In 63 pair years, an average of 0.51 fledglings per pair was found for the former Transvaal province of South Africa.[3] Breeding is characterized as exceptionally erratic but the inconsistencies of their breeding habits in the last few centuries may have unnatural influences, due to this species sensitivity to human disturbance and high rates of persecution they suffer under humans.[3][5][9] Breeding may occur as frequent as in 4 consecutive years or only once every three years with no consistent biannual breeding pattern as in the crowned eagle. In Zimbabwe, a pair studied for 18 years had a replacement rate of 0.44 but bred very erratically: 3 eggs from 4 clutches, then only twice in next 9 years, then reared no young until they bred again and produced 5 young in 5 successive years.[3][5][9][160] The immature eagle, with an average of about four years before it can expect its first breeding season, spends much of its time subsequent to its final separation from its parents looking for feeding opportunities and refining its hunting techniques. There is evidence of a young eagle engaging in a form of play where it throws and tries to catch sticks, a probable form of hunting practice.[3][181] Almost without predators and other natural threats, the martial eagles is quite a long-lived birds with an average lifespan estimated to be 12 to 14 years.[9] The longevity record for a wild eagle of the species is now 31.4 years of age.[182] However, due to fact that they do not reproduce under normal circumstances until they are 6 to 7 years old and their sporadic, widely placed breeding attempts, makes the martial eagle an exceptionally unproductive bird with very low population replacement levels.[161]

Conservation issues

The martial eagle is probably naturally scarce, due to its requirement for large territories and low reproductive rates. Nonetheless, the species has been experiencing a major decline in numbers in recent years, due largely to being directly killed by humans. Its conservation status was uplisted to Near Threatened in 2009 and to Vulnerable in 2013, with another uplisting already expected.[1] As a regional example of their decline: in the former Transvaal Province of South Africa, the total estimated martial eagles present dropped from about 1,500 in the mid-20th century to less than 500 by the 1990s.[2] In terms of the level of decline, it rivals the bateleur as the most reduced of all African eagles, a fact already apparent even up to half a century ago from the 2010s.[3][54] In many areas where they come into contact with humans, eagle populations have decreased greatly through persecution via shooting and poisoning. The reasoning behind such persecution is that martial eagles are taken as a predatory threat to livestock. Despite this perception, in reality domestic animals constitute only a small proportion of the species' diet, whereas the presence of eagles is a sure sign of a healthy environment. In the Cape Province of South Africa, for example, no more than 8% of the diet appeared to consist of domestic stock. This does not take into account, that unlike previously thought, martial eagles do not disdain carrion and some birds, especially immature, are certain to attend carcasses of livestock at times, leading to them being mistaken as stock-killers.[3][53] 76% of martial eagles, almost all of which were clearly shot, brought into the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe were immature ones, thus immature martial eagles are far more prone to come to livestock as a food source.[3] However, martial eagles will indeed at times kill not inconsiderable numbers of livestock, including goats and sheep (mostly young kids and lambs), chickens, most variety of pets, piglets and possibly newborn calves.[43][183][184][185] The local name of martial eagles in South Africa is lammervenger (or “lamb catcher”).[185] The total number of livestock that martial eagles kill annually is controversial, as the claims made by farmers rival those of Verreaux's eagles and exceed in quantity those made against wedge-tailed eagles and even the much wider ranging golden eagles (both locally considered dangerous to livestock). Up to several hundred of livestock kills annually are blamed on them in South Africa alone. The martial eagle, alongside Verreaux's, thus takes the unfortunate title of being allegedly the two most dangerous birds in the world to livestock. However biologists have agreed for some time that the numbers claimed to be killed by martial eagles are considerably exaggerated.[3][183][184][186] Into the 21st century, the martial eagle continue to be strongly disliked by farmers and shot at on sight, even by those favorable towards other eagle species.[1][185][187]

In southern Africa, many martial eagles have taken to nesting on high-tension pylons in areas that are now often absent of large trees, it is one of the few raptors to actually possibly reap more benefit than harm from the presence of these (death by collision with wires and pylons is now one of the worst killers of birds of prey, especially in Europe and southern Africa). However, collision with power-lines can be a serious source of mortality, being a common modern problem for especially immature martial eagles, which are less self-assured fliers.[169][188][189][190] Another hazard is caused by steep sided farm reservoirs in South Africa, in which many birds drown. Of 68 eagle drownings there, 38% were martial eagles, the highest percentage of any raptor recorded to be killed by this (again mostly immatures are claimed by this cause of mortality).[3][191] In South Africa, this eagle may have lost 20% of its population in the last three generations due to such collisions.[192] Further exacerbating the problems faced by the martial eagle, habitat destruction and reduction of prey continues to occur at a high rate outside of protected areas. Due to this large swathes of their former breeding range are now unsuitable[2][5] The preservation of this species depends on education of farmers and other local people, and the increase of protected areas where the species can nest and hunt without excessive disturbance.[5][183]

References

- 1 2 3 4 BirdLife International (2013). "Polemaetus bellicosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Ferguson-Lees & Christie, Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company (2001), ISBN 978-0-618-12762-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 Steyn, P. (1983). Birds of prey of southern Africa: Their identification and life histories. Croom Helm, Beckenham (UK). 1983.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Simmons, R.E. (2005). Martial Eagle Polemaetus bellicosus. Roberts’ Birds of southern Africa, 7th edition. Hockey, PAR, Dean, WRJ and Ryan, PG (eds), 538-539.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cloete, D. (2013). Investigating the decline of the Martial Eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus) in South Africa. University of Cape Town.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2017) IUCN Red List for birds. Downloaded from

- 1 2 3 Boshoff, A.F. Martial eagle Polemaetus bellicosus. In: Harrison JA, Allan DG, Underhill LG, Herremanns M, Tree AJ, Parker V, Brown CJ, editors. The atlas of southern African Birds, vol 1. (1997). Randburg: BirdLife South Africa. 192-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Kemp, A.C. (1994). Martial Eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus). Pp. 200-201 in: del Hoyo, Elliott & Sargatal. eds. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 2. ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Brown, L. & Amadon, D. (1986). Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World. The Wellfleet Press. ISBN 978-1555214722.

- 1 2 Amadon, D. (1982). The genera of booted eagles: Aquila and relatives. Journal of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, 14(2-3), 108-121.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lerner, H., Christidis, L., Gamauf, A., Griffiths, C., Haring, E., Huddleston, C.J., Kabra, S., Kocum, A., Krosby, M., Kvaloy, K., Mindell, D., Rasmussen, P., Rov, N., Wadleigh, R., Wink, M. & Gjershaug, J.O. (2017). Phylogeny and new taxonomy of the Booted Eagles (Accipitriformes: Aquilinae). Zootaxa, 4216(4), 301-320.

- 1 2 Lerner, H.R., & Mindell, D.P. (2005). Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 37(2), 327-346.

- 1 2 Redman, N., Stevenson, T., & Fanshawe, J. (2010). Birds of the Horn of Africa: Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia and Socotra. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ↑ Polemaetus bellicosus- University of Michigan Species Profile

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mendelsohn, J.M., Kemp, A.C., Biggs, H.C., Biggs, R., & Brown, C.J. (1989). Wing areas, wing loadings and wing spans of 66 species of African raptors. Ostrich, 60(1), 35-42.

- ↑ Saito, K. (2009). Lead poisoning of Steller’s Sea-Eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) and White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) caused by the ingestion of lead bullets and slugs. Hokkaido Japan. In RT Watson, M. Fuller, M. Pokras, and WG Hunt (Eds.). Ingestion of Lead from Spent Ammunition: Implications for Wildlife and Humans. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho, USA.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- 1 2 3 Biggs, H.C., Kemp, A.C., Mendelsohn, H.P. & Mendelsohn, J.M. (1979). Weights of South African Raptors and Owls. Durban Museum Novitates, 12: 73-81.

- ↑ Bright, J.A., Marugán-Lobón, J., Cobb, S.N., & Rayfield, E.J. (2016). The shapes of bird beaks are highly controlled by nondietary factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(19), 5352-5357.

- 1 2 3 4 Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- 1 2 Stevenson-Hamilton, J. (1954). Wild life in South Africa. Cassell and Co., London.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Watson, Jeff (2010). The Golden Eagle. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-1420-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Musindo, P.T. (2012). Morphological variation in bills and claws in relation to Prey type in Southern African Birds of Prey (Orders Falconiformes and Strigiformes). Thesis, University of Zimbabwe.

- 1 2 3 4 van Eeden, R., Whitfield, D.P., Botha, A., & Amar, A. (2017). Ranging behaviour and habitat preferences of the Martial Eagle: Implications for the conservation of a declining apex predator. PloS one, 12(3), e0173956.

- ↑ L. Brent Vaughan Hill's Practical Reference Library Volume II (NewYork, NY: Dixon, Hanson and Company, 1906)

- ↑ Kovařík, J. (2002). 1809-Orel proti orlu. Hart.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Smeenk, C. (1974). Comparative-ecological studies of some East African birds of prey. Ardea 62 (1-2) : 1-97.

- ↑ North, M.E.W. (1939). Field Notes on certain Raptorials and Water‐Birds in Kenya Colony—Part II. Ibis, 3(4), 617-643.

- ↑ Shlaer, Robert (1972-05-26). "An Eagle's Eye: Quality of the Retinal Image" (PDF). Science. 176 (4037): 920–922. PMID 5033635. doi:10.1126/science.176.4037.920. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ Reymond, L. (1985). Spatial visual acuity of the eagle Aquila audax: a behavioural, optical and anatomical investigation. Vision research, 25(10), 1477-1491.

- ↑ Fox, R., Lehmkuhle, S.W., & Westendorf, D.H. (1976). Falcon visual acuity. Science, 192(4236), 263-265.

- ↑ Chapin, J.P., & Lang, H. (1953). The birds of the Belgian Congo. Part 3/by James P. Chapin. Bulletin of the AMNH; v. 75A.

- ↑ Fowler, D.W., Freedman, E.A., & Scannella, J.B. (2009). Predatory functional morphology in raptors: interdigital variation in talon size is related to prey restraint and immobilisation technique. Plos One, 4(11), e7999.

- 1 2 Blas R. Tabaranza Jr. "Haribon – Ha ring mga Ibon, King of Birds". Haring Ibon's Flight…. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ↑ Prout-Jones, D.V., & Kemp, A.G. (1997). Moult, plumage sequence and maintenance behaviour of a captive male and female crowned eagle, Stephanoaetus coronatus (Aves: Accipitridae). Annals of the Transvaal Museum, 36(Part 19).

- 1 2 Bortolotti G.R. (1984). "Age and sex size variation in Golden Eagles". Journal of Field Ornithology. 55: 54–66.

- ↑ Fowler, J.M.; Cope, J.B. "Notes on the Harpy Eagle in British Guiana". The Auk. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ↑ Worthy, T.H. & Holdaway, R.N. (2002). The Lost World of the Moa: Prehistoric Life of New Zealand. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253340349.

- ↑ Shephard, J.M., Catterall, C.P., & Hughes, J.M. (2004). Discrimination of sex in the White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster, using genetic and morphometric techniques. Emu, 104(1), 83-87.

- ↑ Parry, S.J., Clark, W.S., & Prakash, V. (2002). On the taxonomic status of the Indian Spotted Eagle Aquila hastata. Ibis, 144(4), 665-675.

- ↑ Lewis, A., & Pomeroy, D. (1989). A bird atlas of Kenya. CRC Press.

- 1 2 3 Machange, R.W., Jenkins, A.R., & Navarro, R.A. (2005). Eagles as indicators of ecosystem health: Is the distribution of Martial Eagle nests in the Karoo, South Africa, influenced by variations in land-use and rangeland quality? Journal of Arid Environments, 63(1), 223-243.

- ↑ Herremans, M., & Herremans-Tonnoeyr, D. (2000). Land use and the conservation status of raptors in Botswana. Biological Conservation, 94(1), 31-41.

- ↑ Pennycuick, C.J. (1972). Soaring behaviour and performance of some East African birds, observed from a motor‐glider. Ibis, 114(2), 178-218.

- ↑ Ash, J., & Atkins, J. (2010). Birds of Ethiopia and Eritrea: an atlas of distribution. Bloomsbury Publishing.