Fisher (animal)

| Fisher | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Pekania |

| Species: | P. pennanti |

| Binomial name | |

| Pekania pennanti (Erxleben, 1777) | |

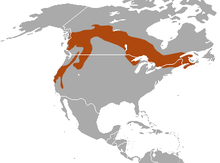

| |

| Fisher range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The fisher (Pekania pennanti) is a small carnivorous mammal native to North America. It is a member of the mustelid family (commonly referred to as the weasel family) and is in the monospecific genus Pekania. The fisher is closely related to but larger than the American marten (Martes americana). The fisher is a forest-dwelling creature whose range covers much of the boreal forest in Canada to the northern United States. Names derived from aboriginal languages include pekan, pequam, wejack, and woolang. It is also called a fisher cat, although it is not a feline.

Males and females look similar. Adult males are 90 to 120 cm (35–47 in) long and weigh 3.5 to 6 kilograms (8–13 lb). Adult females are 75 to 95 cm (30–37 in) long and weigh 2 to 2.5 kg (4–6 lb). The fur of the fisher varies seasonally, being denser and glossier in the winter. During the summer, the color becomes more mottled, as the fur goes through a moulting cycle. The fisher prefers to hunt in full forest. Though an agile climber, it spends most of its time on the forest floor, where it prefers to forage around fallen trees. An omnivore, the fisher feeds on a wide variety of small animals and occasionally on fruits and mushrooms. It prefers the snowshoe hare and is one of the few animals able to prey successfully on porcupines. Despite its common name, the fisher seldom eats fish.

The reproductive cycle of the fisher lasts almost a year. Female fishers give birth to a litter of three or four kits in the spring. They nurse and care for their kits until late summer, when they are old enough to set out on their own. Females enter estrus shortly after giving birth and leave the den to find a mate. Implantation of the blastocyst is delayed until the following spring, when they give birth and the cycle is renewed.

Fishers have few predators besides humans. They have been trapped since the 18th century for their fur. Their pelts were in such demand that they were extirpated from several parts of the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Conservation and protection measures have allowed the species to rebound, but their current range is still reduced from its historic limits. In the 1920s, when pelt prices were high, some fur farmers attempted to raise fishers. However, their unusual delayed reproduction made breeding difficult. When pelt prices fell in the late 1940s, most fisher farming ended. While fishers usually avoid human contact, encroachments into forest habitats have resulted in some conflicts.

Etymology

Despite the name fisher, the animal is not known to eat fish. The name is instead related to the word fitch, meaning a European polecat (Mustela putorius) or pelt thereof, due to the resemblance to that animal. The name comes from colonial Dutch equivalent fisse or visse. In the French language, the pelt of a polecat is also called fiche or fichet.[2]

In some regions, the fisher is known as a pekan, derived from its name in the Abenaki language. Wejack is an Algonquian word (cf. Cree wuchak, otchock, Ojibwa ojiig) borrowed by fur traders. Other American Indian names for the fisher are Chipewyan thacho[3] and Carrier chunihcho,[4] both meaning "big marten", and Wabanaki uskool.[2]

Taxonomy

The Latin specific name pennanti is named for Thomas Pennant, who described the fisher in 1771. Buffon had first described the creature in 1765, calling it a pekan. Pennant examined the same specimen but called it a fisher, unaware of Buffon's earlier description. Other 18th-century scientists gave it similar names, such as Schreber, who named it Mustela canadensis, and Boddaert, who named it Mustela melanorhyncha.[5] The fisher was eventually placed in the genus Martes by Smith in 1843.[6]

Members of the genus Martes are distinguished by their four premolar teeth on the upper and lower jaws. Its close relative Mustela has just three. The fisher has 38 teeth. The dentition formula is:3.1.4.12.1.4.2[7]

Evolution

There is evidence that ancestors of the fisher migrated to North America during the Pliocene era between 2.5 and 5 million years ago. Two extinct mustelids, M. palaeosinensis and M. anderssoni, have been found in eastern Asia. The first true fisher, M. divuliana, has only been found in North America. There are strong indications that M. divuliana is related to the Asian finds, which suggests a migration. M. pennanti has been found as early as the Late Pleistocene era, about 125,000 years ago. There are no major differences between the Pleistocene fisher and the modern fisher. Fossil evidence indicates that the fisher's range extended farther south than it does today.[2]

Three subspecies were identified by Goldman in 1935, M.p. columbiana, M.p. pacifica, and M.p. pennanti. Later research has debated whether these subspecies could be positively identified. In 1959, E.M. Hagmeier concluded that the subspecies are not separable based on either fur or skull characteristics. Although some debate still exists, in general it is recognized that the fisher is a monotypic species with no extant subspecies.[8]

Biology and behavior

Physical characteristics

Fishers are a medium-sized mammal, comparable in size to the domestic cat, and the largest species in the marten genus. Their bodies are long, thin, and low to the ground. The sexes have similar physical features but they are sexually dimorphic in size, with the male being much larger than the female. Males are 90 to 120 cm (35–47 in) in length and weigh 3.5 to 6 kg (8–13 lb). Females measure 75 to 95 cm (30–37 in) and weigh 2 to 2.5 kg (4–6 lb).[9][10] The largest male fisher ever recorded weighed 9 kg (20 lb).[11]

The fisher's fur changes with the season and differs slightly between sexes. Males have coarser coats than females. In the early winter, the coats are dense and glossy, ranging from 30 mm (1 in) on the chest to 70 mm (3 in) on the back. The color ranges from deep brown to black, although it appears to be much blacker in the winter when contrasted with white snow. From the face to the shoulders, fur can be hoary-gold or silver due to tricolored guard hairs. The underside of a fisher is almost completely brown except for randomly placed patches of white or cream-colored fur. In the summer, the fur color is more variable and may lighten considerably. Fishers undergo moulting starting in late summer and finishing by November or December.[12]

Fishers have five toes on each foot, with unsheathed, retractable claws.[2] Their feet are disproportionately large for their legs, making it easier for them to move on top of snow packs. In addition to the toes, there are four central pads on each foot. On the hind paws there are coarse hairs that grow between the pads and the toes, giving them added traction when walking on a variety of surfaces.[13] Fishers have highly mobile ankle joints that can rotate their hind paws almost 180 degrees, allowing them to maneuver well in trees and climb down head-first.[14][15] The fisher is one of relatively few mammalian species with the ability to descend trees head-first.[16]

A circular patch of hair on the central pad of their hind paws marks plantar glands that give off a distinctive odor. Since these patches become enlarged during breeding season, they are likely used to make a scent trail to allow fishers to find each other so that they can mate.[13]

Hunting and diet

Fishers are generalist predators. Although their primary prey is snowshoe hare and porcupine, they are also known to supplement their diet with insects, nuts, berries, and mushrooms. Since they are solitary hunters, their choice of prey is limited by their size. Analyses of stomach contents and scat have found evidence of birds, small mammals, and even moose and deer—the latter two indicating that they are not averse to eating carrion. Fishers have been seen to feed on deer carcasses.[17] While the behavior is not common, fishers have been known to kill larger animals, such as wild turkey, bobcat, and lynx.[18][19][20]

Fishers are one of the few predators that seek out and kill porcupines. There are stories in popular literature that fishers can flip a porcupine onto its back and "scoop out its belly like a ripe melon".[21] This was identified as an exaggerated misconception as early as 1966.[22] Observational studies show that fishers will make repeated biting attacks on the face of a porcupine and kill it after about 25–30 minutes.[23]

Reproduction

The female fisher begins to breed at about one year of age and her reproductive cycle is an almost year-long event. Mating takes place in late March to early April. Blastocyst implantation is then delayed for 10 months until mid-February of the following year when active pregnancy begins. After gestating for about 50 days, the female gives birth to one to four kits.[24] The female then enters estrus 7–10 days later and the breeding cycle begins again.[25]

Females den in hollow trees. Kits are born blind and helpless. They are partially covered with fine hair. Kits begin to crawl after about 3 weeks. After about 7 weeks they open their eyes. They start to climb after 8 weeks. Kits are completely dependent on their mother's milk for the first 8–10 weeks, after which they begin to switch to a solid diet. After 4 months, kits become intolerant of their litter mates, and at 5 months, the mother pushes them out on their own. After one year, juveniles will have established their own range.[25]

Social structure and home range

Fishers are generally crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk. They are active year-round. Fishers are solitary, associating with other fishers only for mating purposes. Males become more active during mating season. Females are least active during pregnancy and gradually increase activity after birth of their kits.[25]

A fisher's hunting range varies from 6.6 km2 (3 sq mi) in the summer to 14.1 km2 (5 sq mi) in the winter. Ranges of up to 20.0 km2 (8 sq mi) in the winter are possible depending on the quality of the habitat. Male and female fishers have overlapping territories. This behavior is imposed on females by males due to dominance in size and a male desire to increase mating success.[26]

Parasites

Parasites of fishers include Baylisascaris devosi, Taenia sibirica, nematode Physaloptera sp., Alaria mustelae, trematode Metorchis conjunctus, nematode Trichinella spiralis and Molineus sp.[27]

Habitat

Although fishers are competent tree climbers, they spend most of their time on the forest floor and prefer continuous forest to other habitats. Fishers have been found in extensive conifer forests typical of the boreal forest but are also common in mixed hardwood and conifer forests. Fishers prefer areas with continuous overhead cover with greater than 80% coverage and will avoid areas with less than 50% coverage.[28] Fishers are more likely to be found in old-growth forests. Since female fishers require moderately large trees for denning, forests that have been heavily logged and have extensive second growth appears to be unsuitable for their needs.[29]

Another factor that fishers select for are forest floors that have large amounts of coarse woody debris. In western forests, where fire regularly removes understorey debris, fishers show a preference for riparian woodland habitat.[26][30][31] Fishers tend to avoid areas with deep snow. Habitat is also affected by snow compaction and moisture content.[32]

Distribution

Fishers are widespread throughout the northern forests of North America. They are found from Nova Scotia in the east to the Pacific shore of British Columbia and Alaska. They can be found as far north as Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories and as far south as the mountains of Oregon. There are isolated populations in the Sierra Nevada of California and the Appalachian Mountains of Pennsylvania, West Virginia,[33] and Virginia[34]

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, fishers were virtually eliminated from the southern and eastern parts of their range including most American states and eastern Canada including Nova Scotia. Over-trapping and loss of forest habitat were the reasons for the decline.[35][36]

Most states had placed restrictions on fisher trapping by the 1930s, coincidental with the end of the logging boom. A combination of forest regrowth in abandoned farmlands and improved forest management practices increased available habitat and allowed remnant populations to recover. Populations have since recovered sufficiently that the species is no longer endangered. Increasing forest cover in eastern North America means that fisher populations will remain sufficiently robust for the near future. Between 1955 and 1985, some states had allowed limited trapping to resume. In areas where fishers were eliminated, porcupine populations subsequently increased. Areas with a high density of porcupines were found to have extensive damage to timber crops. In these cases, fishers were reintroduced by releasing adults relocated from other places into the forest. Once the fisher populations became reestablished, porcupine numbers returned to natural levels.[37] In Washington State, fisher sightings were reported into the 1980s, but an extensive survey in the 1990s did not locate any.[38]

Scattered fisher populations now exist in the Pacific Northwest. In 1961, fishers from British Columbia and Minnesota were re-introduced in Oregon to the southern Cascades near Klamath Falls and also to the Wallowa Mountains near La Grande. From 1977–1980, fishers were introduced to the region around Crater Lake.[39] Starting in January 2008, fishers were reintroduced into Washington State.[40] The initial reintroduction was on the Olympic peninsula (90 animals), with subsequent reintroductions into the south Cascade mountains. The reintroduced animals are monitored by radio collars and remote cameras, and have been shown to be reproducing.[41] From 2008 to 2011, about 40 fishers were re-introduced in the northern Sierra Nevada near Stirling City, complementing fisher populations in Yosemite National Park and along California's northern boundary between the Pacific Coast Ranges and the Klamath Mountains.[42] Fishers are a protected species in Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming. In Idaho and California, fishers are protected through a closed trapping season, but they are not afforded any specific protection;[43] however, in California the fisher has been granted threatened status under the Endangered Species Act.[44] In June 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recommended that fishers be removed from the endangered list in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. It also recommended further study to ensure that current populations are managed properly.[10]

Recent studies, as well as anecdotal evidence, show that fishers have begun making inroads into suburban backyards, farmland, and periurban areas in several US states and eastern Canada, as far south as most of northern Massachusetts, New York,[45][46] Connecticut,[47] Minnesota and Iowa,[48] and even rural New Jersey.[49] Some reports have shown that populations have become established on Cape Cod,[50] although the populations are likely smaller than the populations in the western part of New England.[51][52]

Fishers and people

Fishers have had a long history of contact with humans, but most of it has been to the detriment of fisher populations. Unprovoked attacks on humans are extremely rare, but fishers will attack if they feel threatened or cornered. In one case, a fisher was blamed for an attack on a six-year-old boy.[53][54] In another case, a fisher is believed to be responsible for an attack on a twelve-year-old boy.[55]

In 2003, a new minor league baseball team based in Manchester, New Hampshire, held a "Name The Team" contest; the name New Hampshire Fisher Cats was chosen by the public from a list of suggestions reflecting the local culture and environment.[56]

Fur trade and conservation

Fishers have been trapped since the 18th century. They have been popular with trappers due to the value of their fur, which has been used for scarves and neck pieces. The best pelts are from winter trapping with secondary quality pelts from spring trapping. The lowest-quality furs come from out-of-season trapping when fishers are moulting. They are easily trapped, and the value of their fur was a particular incentive for catching this species.[59]

Prices for pelts have varied considerably over the past 100 years. They were highest in the 1920s and 1930s, when average prices were about $100 US.[60] In 1936, pelts were being offered for sale in New York City for $450–750 per pelt.[61] Prices declined through the 1960s but picked up again in the late 1970s. In 1979, the Hudson's Bay Company paid $410 for one female pelt.[61] In 1999, 16,638 pelts were sold in Canada for $449,307 (CAN) at an average price of $27.[62]

Between 1900 and 1940, fishers were threatened with near-extinction in the southern part of their range due to overtrapping and alterations to their habitat. In New England, fishers, along with most other furbearers, were nearly exterminated due to unregulated trapping. Fishers became extirpated in many northern U.S. states after 1930, but were still abundant enough in Canada to maintain a harvest of over 3,000 fishers per year (see figure). Limited protection was afforded in the early 20th century, but it was not until 1934 that total protection was finally given to the few remaining fishers. Closed seasons, habitat recovery, and reintroductions have restored fishers to much of their original range.[2]

Trapping resumed in the U.S. after 1962 once numbers had recovered sufficiently. During the early 1970s, the value of fisher pelts soared, leading to another population crash in 1976. After a couple of years of closed seasons, fisher trapping re-opened in 1979 with a shortened season and restricted bag limits. The population has steadily increased since then, with steadily increasing numbers of trapped animals, despite a much lower pelt value.[57]

Captivity

_fur-skin.jpg)

Fishers have been captured live for fur farming, zoo specimens, and scientific research. From 1920–1946, pelt prices averaged about $137 CAN. Since pelts were relatively valuable, attempts were made to raise fishers on farms. Fur farming was popular with other species such as mink and ermine, so it was thought that the same techniques could be applied to fishers. However, farmers found it difficult to raise fishers due to their unusual reproductive cycle. In general, knowledge of delayed implantation in fishers was unknown at the time. Farmers noted that females mated in the spring but did not give birth. Due to declining pelt prices, most fisher farms closed operations by the late 1940s.[63]

Fishers have also been captured and bred by zoos, but they are not a common zoo species. Fishers are poor animals to exhibit because, in general, they hide from visitors all day. Some zoos have had difficulty keeping fishers alive since they are susceptible to many diseases in captivity.[64] Yet there is at least one example of a fisher kept in captivity that lived to be ten years old, and one case of a fisher living to be approximately 14 years old,[65] well beyond its natural lifespan of 7 years.[66][67]

In 1974, R.A. Powell raised two fisher kits for the purpose of performing scientific research. His primary interest was an attempt to measure the activity of fishers in order to determine how much food the animals required to function. He did this by running them through treadmill exercises that simulated activity in the wild. He compared this to their food intake and used the data to estimate daily food requirements. The research lasted for two years. After one year, one of the fishers died due to unknown causes. The second was released back into the wilderness of Michigan's Upper Peninsula.[68]

Interactions with domestic animals

In some areas, fishers can become pests to farmers when they raid chicken coops. There have been a few instances of fishers preying on cats and small dogs;[69][70][71][72][73][74] but in general, the evidence suggests these attacks are rare. A 1979 study examined the stomach contents of all fishers trapped in the state of New Hampshire; cat hairs were found in only 1 of over 1,000 stomachs.[75] More recent studies in suburban upstate New York and Massachusetts found no cat remains in 24 and 226 fisher diet samples (scat and stomach contents) respectively.[76] While there is popular belief for more frequent attacks on pets, zoologists suggest bobcats or coyotes are more likely to prey upon domestic cats and chickens.

Poisoning

In 2012, a study conducted by Integral Ecology Research Center, UC Davis, US Forest Service, and the Hoopa Tribe showed that fishers in California were exposed to and killed by anticoagulant rodenticides associated with marijuana cultivation.[77] In this study, 79% of fishers that were tested in California were exposed to an average of 1.61 different anticoagulant rodenticides and four fishers died directly attributed to these toxicants. A 2015 follow-up study building on this data determined that the trend of exposure and mortality from these toxicants increased to 85%, that California fishers were now exposed to an average of 1.73 different anticoagulant rodenticides, and that nine more fishers died, bringing the total to 13.[78] The extent of marijuana cultivation within fishers' home ranges was highlighted in a 2013 study focusing on fisher survival and impacts from marijuana cultivation within the Sierra National Forest.[79] Research showed that fishers had an average of 5.3 individual grow sites within their home range.[79] One fisher had 16 individual grow sites within its territory.

Literature

One of the first mentions of fishers in literature occurred in The Audubon Book of True Nature Stories. Robert Snyder relates a tale of his encounter with fishers in the woods of the Adirondack Mountains of New York. He recounts three sightings, including one where he witnessed a fisher attacking a porcupine.[80]

In Winter of the Fisher, Cameron Langford relates a fictional encounter between a fisher and an aging recluse living in the forest. The recluse frees the fisher from a trap and nurses it back to health. The fisher tolerates the attention, but being a wild animal, returns to the forest when well enough. Langford uses the ecology and known habits of the fisher to weave a tale of survival and tolerance in the northern woods of Canada.[81]

Fishers are mentioned in several other books including The Blood Jaguar (an animal shaman), Ereth's Birthday (a porcupine hunter) and in The Sign of the Beaver, where a fisher is thought to have been caught in a trap.[82][83][84]

Notes

- ↑ Reid, F. & Helgen, K. (2008). "Pekania pennanti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved August 21, 2016. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

- 1 2 3 4 5 Powell, R.A. (1981). "Mammalian Species: Martes pennanti" (PDF). The American Society of Mammalogists: 156:1–6. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Fort Resolution Chipewyan Dictionary" (PDF). January 22, 2011. p. 40. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Poser, William J. (1998). Nak'albun/Dzinghubun Whut'enne Bughuni (Stuart/Trembleur Lake Carrier Lexicon), 2nd edition. Vanderhoof, BC: Yinka Dene Language Institute.

- ↑ Coues, p. 66.

- ↑ Powell, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Powell, p. 12.

- ↑ Powell, p. 14.

- ↑ "Martes pennanti: Fisher". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- 1 2 "Fisher". 2011.

- ↑ Powell, p. 3.

- ↑ Powell, pp. 4–6.

- 1 2 Powell, p. 9.

- ↑ Fergus, p. 101.

- ↑ Nations, Johnathan A.; Link, Olson. "Scansoriality in Mammals". Animal Diversity Web.

- ↑ Alexander, R. McNeill (2003). Principles of animal locomotion. Princeton University Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-691-08678-8.

- ↑ Fergus, p. 102.

- ↑ "Ecological Characteristics of Fishers in the Southern Oregon Cascade Range" (PDF). USDA Forest Service – Pacific Northwest Research Station 2006.

- ↑ Vashon, Jennifer; Vashon, Adam; Crowley, Shannon. "Partnership for Lynx Conservation in Main December 2001 – December 2002 Field Report" (PDF). Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. p. 9.

- ↑ Richardson, John (March 17, 2010). "Researchers collect data to track health of, threats to Canada lynx". The Portland Press Herald. Pressherald.com. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Doyle, Brian (March 6, 2006). "Fishering". High Country News. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Coulter, M.W. (1966). Ecology and management of fishers in Maine. (Ph.D. thesis). Syracuse, N.Y.: St. Univ. Coll. Forest. Syracuse University.

- ↑ Powell, pp. 134–6.

- ↑ Burt, Henry W. (1976) A Field Guide to the Mammals. Boston, p. 55. ISBN 0-395-24084-0.

- 1 2 3 Feldhamer, pp. 638–9.

- 1 2 Feldhamer, p. 641.

- ↑ Dick T. A & Leonard R. D. (1979). "Helminth parasites of fisher Martes pennanti (Erxleben) from Manitoba, Canada". Journal of Wildlife Diseases 15(3): 409-412. PMID 574167.

- ↑ Powell, p. 88.

- ↑ Powell, p. 92.

- ↑ "Fisher Martes pennanti". Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Martes pennanti: North American range map". Discover Life. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Powell, p. 93.

- ↑ Feldhamer, p. 636.

- ↑ "fisher | VDGIF". www.dgif.virginia.gov. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ Powell, p. 77.

- ↑ Hardisky, Thomas, ed. (July 2001). "Pennsylvania Fisher Reintroduction Project". Pennsylvania Game Commission, Bureau of Wildlife Management. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Powell, pp. 77–80.

- ↑ "Threatened and Endangered Wildlife in Washington: 2012 Annual Report" (PDF).

- ↑ Keith B. Aubry; Jeffrey C. Lewis (November 2003). "Extirpation and reintroduction of fishers (Martes pennanti) in Oregon: implications for their conservation in the Pacific states". Biological Conservation. 114: 79–90. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00003-X. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ↑ Mapes, Lynda V (January 28, 2008). "Weasel-like fisher back in state after many decades". Seattle Times. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Threatened and Endangered Species in Washington: 2012 Annual Report" (PDF). Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ Peter Fimrite (2011-12-09). "Fishers returned to area in Sierra after 100 years". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ↑ Zielinski, William J.; Kucera, Thomas E. (1998). American Marten, Fisher, Lynx, and Wolverine: Survey Methods for Their Detection. DIANE Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7881-3628-3. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ↑ "CNDDB Endangered and Threatened Animals List" (PDF). April 1, 2017. p. 13. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ↑ Zezima, Katie (June 10, 2008). "A Fierce Predator Makes a Home in the Suburbs". New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ LaPoint S, Gallery P, Wikelski M, Kays R (2013) Animal behavior, cost-based corridor models, and real corridors. Landscape Ecology 28:1615-1630

- ↑ Polansky, Rob. "West Haven residents concerned over fisher cats". WFSB Eyewitness News. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Trail camera shows fierce mammal not seen in Iowa since 1800s". February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ↑ Kontos, Charles (October 19, 2013). "Rutgers, friends memorialize naturalist Charlie Kontos". Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ Ward, Katy (2017-03-23). "Fisher cat found dead on the beach near MacMillan Pier". Wicked Local Provincetown. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ Davis, Chase (November 13, 2005). "Elusive fisher cats returning to Cape". Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ Brennan, George (April 3, 2008). "Rare Cape fisher caught on camera". Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Fisher cat attacks boy". Westerly Sun.

- ↑ "Fisher Cat Attacks Child at Bus Stop". FOX News, Providence, RI. June 23, 2009. Archived from the original on March 6, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Family says boy, 12, attacked by fisher cat". WCVB News. July 1, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ↑ "'Fisher Cats' Chosen For Baseball Team Name". December 3, 2003. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- 1 2 Milan Novak, ed. (1987). Furbearer harvests in North America, 1600–1984. Ontario Trappers Association.

- ↑ "Bank of Canada inflation calculator". Bank of Canada. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ↑ Hodgson, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Powell, Roger A. Martes pennanti. The American Society of Mammalogists. May 8, 1981.

- 1 2 Hodgson, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Statistics Canada. Agriculture Division (2008). Fur Statistics (Report).

- ↑ Hodgson, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Powell, pp. 207–8.

- ↑ "Feds issue notice after Pacific fisher dies at HSU". times-standard.com.

- ↑ New York Zoological Society (1971). Bronx Zoo (Report).

- ↑ "Basic Facts About Fishers". Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ↑ Powell, pp. xi–xv.

- ↑ "Weasel-like fishers rebound; backyard pets become prey". San Diego Union-Tribune. June 12, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Fisher: The fisher is a North American marten, a medium sized mustelid". Science Daily. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ "What is a Fisher Cat?". WPRI.com. June 23, 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Fisher [sic] in Massachusetts". Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ O'Brian, Brian (August 25, 2005). "On the wild side: Once nearly extinct, weasel-like fishers thrive in the suburbs, where their ravenous feeding habits threaten family pets". Boston Globe. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Fahim, Kareem (July 4, 2007). "A Cat Fight? Sort of, only louder and uglier". New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Orff, Eric B. "The Fisher: New Hampshire's Rodney Dangerfield". New Hampshire Fish and Wildlife News. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Kays, Roland (April 6, 2011). "Do Fishers Really Eat Cats?". New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ Gabriel, Mourad W.; Woods, Leslie W.; Poppenga, Robert; Sweitzer, Rick A.; Thompson, Craig; Matthews, Sean M.; Higley, J. Mark; Keller, Stefan M.; Purcell, Kathryn (July 13, 2012). "Anticoagulant Rodenticides on our Public and Community Lands: Spatial Distribution of Exposure and Poisoning of a Rare Forest Carnivore". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e40163. PMC 3396649

. PMID 22808110. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040163.

. PMID 22808110. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040163. - ↑ Gabriel, Mourad W.; Woods, Leslie W.; Wengert, Greta M.; Stephenson, Nicole; Higley, J. Mark; Thompson, Craig; Matthews, Sean M.; Sweitzer, Rick A.; Purcell, Kathryn (November 4, 2015). "Patterns of Natural and Human-Caused Mortality Factors of a Rare Forest Carnivore, the Fisher (Pekania pennanti) in California". PLoS ONE. 10 (11): e0140640. PMC 4633177

. PMID 26536481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140640.

. PMID 26536481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140640. - 1 2 Thompson, Craig; Sweitzer, Richard; Gabriel, Mourad; Purcell, Kathryn; Barrett, Reginald; Poppenga, Robert (March 1, 2014). "Impacts of Rodenticide and Insecticide Toxicants from Marijuana Cultivation Sites on Fisher Survival Rates in the Sierra National Forest, California". Conservation Letters. 7 (2): 91–102. ISSN 1755-263X. doi:10.1111/conl.12038.

- ↑ Snyder, Robert G. (1958). Terres JK, ed. The Audubon Book of True Nature Stories. Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York. pp. 205–9.

- ↑ Langford, Cameron (1971). Winter of the Fisher. Macmillan of Canada Company, Toronto, Ontario. ISBN 0-7089-2937-0.

- ↑ Payne, Michael H. (1998). The Blood Jaguar. Tor, New York. ISBN 0-312-86783-2.

- ↑ Avi (2000). Ereth's Birthday. HarperCollins, New York. ISBN 0-380-80490-5.

- ↑ Speare, Elizabeth George (1983). The Sign of the Beaver. Bantam Doubleday Dell Books for Young Readers, New York. ISBN 0-547-34870-3.

References

- Coues, Elliott (1877). Fur Bearing Animals: a Monograph of North American Mustelidae. Department of the Interior (US). pp. 62–74. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Feldhamer, George A.; Thompson, Bruce C.; Chapman, Joseph A. (2003). Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and conservation. (Google books limited preview) Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 635–649. ISBN 0-8018-7416-5. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Fergus, Charles (2006). Wildlife of Virginia and Maryland and Washington. Stackpole Books. pp. 101–103. ISBN 0-8117-2821-8. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Hodgson, Robert G. (1937). Fisher Farming. Fur Trade Journal of Canada.

- Powell, Roger A. (November 1993). The Fisher: Life History, Ecology, and Behavior. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-2266-5.

Further reading

- Buskirk, Steven W.; Harestad, Alton S.; Raphael, Martin G.; Powell, Roger A. (1994). Martens, sables, and fishers: biology and conservation. Comstock Publishing Associates. ISBN 978-0-8014-2894-4.

External links

- Fisher videos, photos and facts Arkive.org.

- Fisher Cat Screech Online community of fisher cat sightings, sounds, and videos.

-

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Fisher". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Fisher". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Fisher". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.