Mars 2020

|

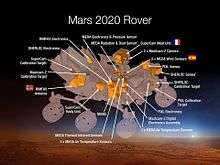

Computer-design drawing for NASA's 2020 Mars Rover | |

| Mission type | Rover |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| Website | http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/mars2020/ |

| Mission duration | Planned: 1 Mars year[1] |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | July 2020 (planned)[1] |

| Rocket | Atlas V 541[2] |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-41 |

| Mars rover | |

| Spacecraft component | Rover |

Mars 2020 is a Mars rover mission by NASA's Mars Exploration Program with a planned launch in 2020.[1] It is intended to investigate an astrobiologically relevant ancient environment on Mars, investigate its surface geological processes and history, including the assessment of its past habitability, the possibility of past life on Mars, and potential for preservation of biosignatures within accessible geological materials.[3][4]

The as-yet unnamed Mars 2020 was announced by NASA on 4 December 2012 at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.[5] The rover's design will be derived from the Curiosity rover, but will carry a different scientific payload.[6] Nearly 60 proposals[7][8] for rover instrumentation were evaluated and, on 31 July 2014, NASA announced the payload for the rover.[9][10]

Mission

| Year | Launch | C3-Launch energy |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Apr 2018 – May 2018 | 7.7–11.1 km2/s2 |

| 2020 | Jul 2020 – Sep 2020 | 13.2 - 18.4 km2/s2 |

The rover is planned to be launched in 2020.[5] The Jet Propulsion Laboratory will manage the mission. The payload and science instruments for the mission were selected in July 2014 after an open competition for payloads[9] based on scientific objectives set one year earlier.[12] However, the mission is contingent on receiving adequate funding.[13] Precise mission details will be determined by the mission's Science Definition Team.[14]

In May 2017, evidence of the earliest known life on land may have been found in 3.48-billion-year-old geyserite, a mineral deposit often found around hot springs and geysers, uncovered in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia.[15][16] These findings may be helpful in deciding where best to search for early signs of life on the planet Mars.[15][16]

Proposed objectives

The mission is part of NASA's Mars Exploration Program,[17] and its Mars Program Planning Group (MPPG), as well as the associate administrator of science John Grunsfeld, endorsed a sample retrieval and return mission to Earth for scientific analysis.[18][19][20] Regardless, a mission requirement is that it must help prepare NASA for its long-term sample return or manned mission efforts.[4][20][21]

On 9 July 2013, the Mars 2020 Science Definition Team reiterated that the rover should look for signs of past life, collect samples for possible future return to Earth, and demonstrate technology for future human exploration of Mars. The Science Definition Team proposed the rover collect and package as many as 31 samples of rock cores and soil for a later mission to bring back for more definitive analysis in laboratories on Earth, but in 2015 the concept was changed to collect even more samples and distribute the tubes in small piles across the surface of Mars. However, returning the samples to Earth would likely require two additional missions: one rover to land on Mars, take the samples collected by Mars 2020, and launch them into Mars orbit; and another to collect the sample canister in Mars orbit and return it to Earth. Neither of those missions is under development by NASA,[22][23] but it has been suggested that the proposed Mars 2022 orbiter may play a role in such future mission.[22][24]

In September 2013 NASA launched an Announcement of Opportunity for researchers to propose and develop the instruments needed, including a core sample cache.[25][26] The science conducted by the rover's instruments would provide the context needed to make informed decisions about whether to return the samples to Earth.[27] The chairman of the Science Definition Team stated that NASA does not presume that life ever existed on Mars, but given the recent Curiosity rover findings, past Martian life seems possible.[27]

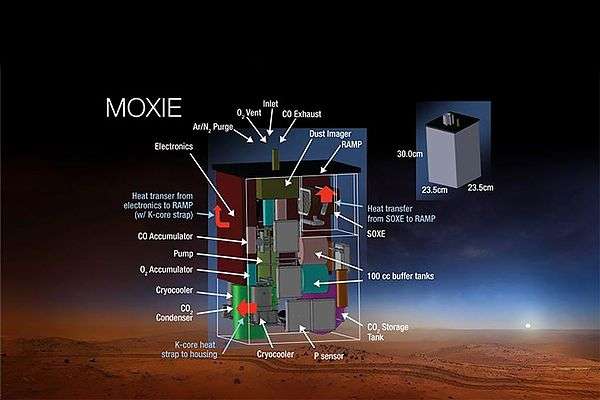

The rover can make measurements and technology demonstrations to help designers of a human expedition understand any hazards posed by Martian dust, and will test technology to produce oxygen (O2) from Martian atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2).[28] Improved precision landing technology that enhances the scientific value of robotic missions also will be critical for eventual human exploration on the surface.[29] Based on input from the Science Definition Team, NASA defined the final objectives for the 2020 rover. Those become the basis for soliciting proposals to provide instruments for the rover's science payload in the spring 2014.[28]

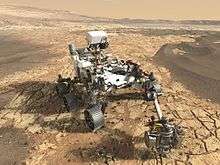

Design

As proposed, the rover will be based on the design of Curiosity.[5] While there will be differences in scientific instruments and the engineering required to support them, the entire landing system (including the sky crane and heat shield) and rover chassis can essentially be recreated without any additional engineering or research. This reduces overall technical risk for the mission, while saving funds and time on development.[30] One of the upgrades is a guidance and control technique called "Terrain Relative Navigation" to fine-tune steering in the final moments of landing.[31] The rover will have thicker, more durable wheels, with reduced width and a greater diameter than Curiosity's.[32]

A Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, left over as a backup part for Curiosity during its construction, will power the rover.[5][33]

The rover mission and launch is estimated to cost about US$2.1 billion.[22] The mission's predecessor, the Mars Science Laboratory, cost US$2.5 billion in total.[5] The availability of spare parts will make the new rover somewhat more affordable. Curiosity's engineering team are also involved in the rover's design.[5][14]

In October 2016, NASA reported using the Xombie rocket to test the Landing Vision System (LVS), as part of the Autonomous Descent and Ascent Powered-flight Testbed (ADAPT) experimental technologies, for the Mars 2020 mission landing.[34]

Proposed scientific instruments

- Planetary Instrument for X-Ray Lithochemistry (PIXL), an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer to determine the fine scale elemental composition of Martian surface materials.[35][36]

- Radar Imager for Mars' subsurface experiment (RIMFAX), a ground-penetrating radar to image dozens of meters beneath the rover.[37][38][39]

- Mars Environmental Dynamic Analyzer (MEDA), a set of sensors that will provide measurements of temperature, wind speed and direction, pressure, relative humidity and dust size and shape. It would be provided by Spain's Centro de Astrobiología.[40]

- The Mars Oxygen ISRU Experiment (MOXIE) is an exploration technology investigation that will produce oxygen (O2) from Martian atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2).[41] This technology could be scaled up in the future for human life support or make rocket fuel for return missions.[42]

- SuperCam, an instrument that can provide imaging, chemical composition analysis and mineralogy in rocks and regolith from a distance. It is similar to the ChemCam on the Curiosity rover but with four scientific instruments that will allow it to look for biosignatures.[43]

- Mastcam-Z, a stereoscopic imaging system with the ability to zoom.

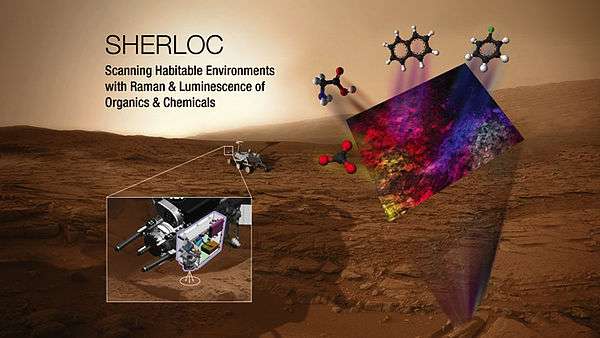

- Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals (SHERLOC), an ultraviolet Raman spectrometer that uses fine-scale imaging and an ultraviolet (UV) laser to determine fine-scale mineralogy and detect organic compounds.[44][45]

- Mars Helicopter Scout (MHS) is a solar powered helicopter drone with a mass of 1 kg (2.2 lb) that could help pinpoint interesting targets for study and plan the best driving route.[46][47] The helicopter would fly no more than 3 minutes per day and cover a distance of about 1 km (0.62 mi) daily.[48] It has coaxial rotors, a high resolution downward looking camera for navigation, landing, and science surveying of the terrain, and a communication system to relay data to the rover.[49] $15 million is being requested to keep development of the helicopter on track.[50]

- Microphones will be used during the landing event, while driving, and when collecting samples.[51]

| Proposed Mars 2020 rover instruments | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Proposed landing sites

The following locations are the eight landing sites that were under consideration for Mars 2020[52] previous to the meeting in Pasedena, California Feb 2017.

- Columbia Hills, in Gusev Crater

- Eberswalde Crater

- Holden Crater

- Jezero Crater[53][54]

- Mawrth Vallis

- Northeastern region of Syrtis Major Planum

- Nili Fossae

- Southwestern region of Melas Chasma

A workshop was held on 8–10 February 2017 in Pasadena, California, to discuss these sites, with the goal of narrowing down the list to 3-4 final sites for further consideration.[55] The selected sites are:[56]

- Jezero Crater

- Northeastern region of Syrtis Major Planum

- Columbia Hills, in Gusev Crater, where the Spirit rover landed

Reactions

In reaction to the announcement, California U.S. Representative Adam Schiff came out in support of the Mars rover mission plans, saying that "an upgraded rover with additional instrumentation and capabilities is a logical next step that builds upon now proven landing and surface operations systems."[5] Schiff also said he favored an expedited launch in 2018 which would enable an even greater payload to be launched to Mars. Schiff said he would be working with NASA, White House administration and Congress to explore the possibility of advancing the launch date.[5]

NASA's science chief John Grunsfeld responded that while it could be possible to launch in 2018, "it would be a push." Grunsfeld said a 2018 launch would require certain science investigations be excluded from the rover and that even the 2020 launch target would be "ambitious."[5]

Space educator Bill Nye added his support for the planned mission saying, “We don't want to stop what we're doing on Mars because we're closer than ever to answering these questions: Was there life on Mars and stranger still, is there life there now in some extraordinary place that we haven't yet looked at? Mars was once very wet—it had oceans and lakes. Did life start on Mars and get flung into space and we are all descendants of Martian microbes? It's not crazy, and it's worth finding out. It's worth the cost of a cup of coffee per taxpayer every 10 years or 13 years to find out.” Nye also endorsed a Mars sample-return role, saying “The amount of information you can get from a sample returned from Mars is believed to be extraordinarily fantastic and world-changing and worthy."[57]

The selection has been criticized for NASA's constant attention to Mars,[58] and neglecting other Solar System destinations in constrained budget times. Contrary to usual NASA practices, the mission was approved for flight before a Science Definition Team (SDT) had been formed to decide on the mission's purpose and goals.

Images

| Proposed landing site – Jezero crater[54][59] (18°51′18″N 77°31′08″E / 18.855°N 77.519°E)[60] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Mars 2020 (NASA, July 2013) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Mission: Overview". NASA. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Ray, Justin (25 July 2016). "NASA books nuclear-certified Atlas 5 rocket for Mars 2020 rover launch". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Chang, Alicia (9 July 2013). "Panel: Next Mars rover should gather rocks, soil". AP News. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- 1 2 Cowing, Keith (21 December 2012). "Science Definition Team for the 2020 Mars Rover". NASA. SpaceRef. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Harwood, William (4 December 2012). "NASA announces plans for new $1.5 billion Mars rover". CNET. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

Using spare parts and mission plans developed for NASA's Curiosity Mars rover, the space agency says it can build and launch the rover in 2020 and stay within current budget guidelines.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (4 December 2012). "Nasa to send new rover to Mars in 2020". BBC News. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (21 January 2014). "NASA Receives Mars 2020 Rover Instrument Proposals for Evaluation". NASA. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ Timmer, John (31 July 2014). "NASA announces the instruments for the next Mars rover". ARS Technica. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- 1 2 Brown, Dwayne (31 July 2014). "RELEASE 14-208 – NASA Announces Mars 2020 Rover Payload to Explore the Red Planet as Never Before". NASA. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne (31 July 2014). "NASA Announces Mars 2020 Rover Payload to Explore the Red Planet as Never Before". NASA. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ McCleese, Daniel J. (March 2006). "Robotic Mars Exploration Strategy, 2007–2016" (PDF). Mars Advanced Planning Group 2006. NASA: 27. JPL 400–1276.

- ↑ "Objectives – 2020 Mission Plans". mars.nasa.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ↑ "Update on NASA Mars Rover Plans". www.planetary.org. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- 1 2 Wall, Mike (4 December 2012). "NASA to Launch New Mars Rover in 2020". Space.com. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- 1 2 Staff (9 May 2017). "Oldest evidence of life on land found in 3.48-billion-year-old Australian rocks". Phys.org. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- 1 2 Djokic, Tara; Van Kranendonk, Martin J.; Campbell, Kathleen A.; Walter, Malcolm R.; Ward, Colin R. (9 May 2017). "Earliest signs of life on land preserved in ca. 3.5 Ga hot spring deposits". Nature Communications. doi:10.1038/ncomms15263. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ↑ Program And Missions – 2020 Mission Plans. NASA, 2015.

- ↑ Mann, Adam (4 December 2012). "NASA Announces New Twin Rover for Curiosity Launching to Mars in 2020". Wired. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ "Mars Planning Group Endorses Sample Return". SpaceNews. 3 October 2012. (subscription required)

- 1 2 Summary of the MPPG Final Report

- ↑ Moskowitz, Clara (5 February 2013). "Scientists Offer Wary Support for NASA's New Mars Rover". Space.com. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 Mars 2020 rover mission to cost more than $2 billion. Jeff Foust Space News, 20 July 2016.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Jake (12 October 2015). "Mars 2020 and the Adaptive Caching Assembly: An Intern’s Perspective". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Evans, Kim (13 October 2015). "NASA Eyes Sample-Return Capability for Post-2020 Mars Orbiter". Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ "Announcement of Opportunity: Mars 2020 Investigations" (PDF). NASA. 24 September 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ "Mars 2020 Mission: Instruments". NASA. 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Science Team Outlines Goals for NASA's 2020 Mars Rover". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. 9 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- 1 2 Klotz, Irene (21 November 2013). "Mars 2020 Rover To Include Test Device To Tap Planet’s Atmosphere for Oxygen". Space News. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (2 September 2014). "Curiosity EDL data to provide 2020 Mars Rover with super landing skills". NASA Space Flight. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ Dreier, Casey (10 January 2013). "New Details on the 2020 Mars Rover". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "Mars 2020 Rover: Entry, Descent, and Landing System". NASA. July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ Gebhardt, Chris. "Mars 2020 rover receives upgraded eyesight for tricky skycrane landing". Nasaspaceflight. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (4 December 2012). "NASA plans 2020 Mars rover remake". Cosmic Log. NBC News. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ Williams, Leslie; Webster, Guy; Anderson, Gina (4 October 2016). "NASA Flight Program Tests Mars Lander Vision System". NASA. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- 1 2 Webster, Guy (31 July 2014). "Mars 2020 Rover's PIXL to Focus X-Rays on Tiny Targets". NASA. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "Adaptive sampling for rover x-ray lithochemistry" (PDF).

- ↑ "RIMFAX, The Radar Imager for Mars' Subsurface Experiment". NASA. July 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Chung, Emily (19 August 2014). "Mars 2020 rover's RIMFAX radar will 'see' deep underground". Canadian Broadcasting Corp. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ↑ U of T scientist to play key role on Mars 2020 Rover Mission

- ↑ In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). GCD-NASA.

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth (31 July 2014). "NASA to test making rocket fuel ingredient on Mars". AP News. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ Webb, Jonathan (1 August 2014). "Mars 2020 rover will pave the way for future manned missions". BBC News. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ NASA Administrator Signs Agreements to Advance Agency's Journey to Mars. 16 June 2015.

- 1 2 Webster, Guy (31 July 2014). "SHERLOC to Micro-Map Mars Minerals and Carbon Rings". NASA. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "SHERLOC: Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals, an Investigation for 2020" (PDF).

- ↑ "NASA Is Developing A Helicopter Drone For 2020 Mars Mission". Business 2 Community. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ Leone, Dan (19 November 2015). "Elachi Touts Helicopter Scout for Mars Sample-Caching Rover". Space News. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ "Crazy Engineering Mars Helicopter Transcript" (PDF). JPL – NASA. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ Volpe, Richard. "2014 Robotics Activities at JPL" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (24 May 2016). "Four wild technologies lawmakers want NASA to pursue". ARS Technica. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ Strickland, Ashley (15 July 2016). "New Mars 2020 rover will be able to 'hear' the Red Planet". CNN News. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Farley, Ken (8 September 2015). "Researcher discusses where to land Mars 2020". Phys.org. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ Hand, Eric (6 August 2015). "Mars scientists tap ancient river deltas and hot springs as promising targets for 2020 rover". Science News. Science News. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- 1 2 "PIA19303: A Possible Landing Site for the 2020 Mission: Jezero Crater". NASA. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ "2020 Landing Site for Mars Rover Mission". NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ↑ Witze, Alexandra (11 February 2017). "Three sites where NASA might retrieve its first Mars rock". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21470. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ↑ Rosie Mestel (6 December 2012). "Bill Nye, the (planetary) science guy, on NASA's future". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ Matson, John (21 February 2013). "Has NASA Become Mars-Obsessed?". Scientific American. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ↑ Goudge, Timothy A.; Mustard, John F.; Head, James W.; Fassett, Caleb I.; Wiseman, Sandra M. (6 March 2015). "Assessing the Mineralogy of the Watershed and Fan Deposits of the Jezero Crater Paleolake System, Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research. doi:10.1002/2014JE004782.

- ↑ Wray, James (6 June 2008). "Channel into Jezero Crater Delta". NASA. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mars 2020. |

- Mars 2020 website

- Mars 2020 Science Definition Team Report at NASA.gov

- Proposed 2020 Mars Rover Science Goals (July 2013) on YouTube

- Mars 2020 Rover and Beyond News Teleconference (July 2014) on YouTube

.jpg)

.jpg)