Marriage and wedding customs in the Philippines

Traditional marriage customs in the Philippines and Filipino wedding practices pertain to the characteristics of marriage and wedding traditions established and adhered by them Filipino men and women in the Philippines after a period of courtship and engagement. These traditions extend to other countries around the world where Filipino communities exist. Kasalan is the Filipino word for "wedding",[1] while its root word – kasal – means "marriage".[2] The present-day character of marriages and weddings in the Philippines were primarily influenced by the permutation of Filipino, Christian, Catholic, Protestant, Chinese, Spanish,[1] and American models.

Historical overview

A typical ancient traditional Filipino wedding, during pre-colonial times, is held for three days and was officiated by a babaylan, a tribal priest or priestess.[3][4] The house of the babaylan was the ceremonial center for the nuptial. On the first day, the couple was brought to the priest's home, where the babaylan blesses them, while their hands are joined over a container of uncooked rice. On the third day, the priest would prick their chests to draw a small amount of blood, which will be placed on a container to be mixed with water. After announcing their love for each other three times, they were fed by the priest with cooked rice coming from a single container. Afterwards, they were to drink the water that was mixed with their blood. The priest proclaimed that they are officially wed after their necks and hands were bound by a cord or, sometimes, once their long hairs had been entwined together.[3][4] In lieu of the babaylan, the datu or a wise elder may also officiate a pre-colonial Filipino wedding.[4]

After the ceremony, a series of gift-exchanging rituals was also done to counter the negative responses of the bride: if asked to enter her new home, if she refuses to go up the stairs of the dwelling, if she denies to participate in the marriage banquet, or even to go into her new bedroom, a room she would be sharing with her spouse.[4]

Spanish colonialism brought changes to these marriage rituals because of the teachings and conversion efforts of Spanish missionaries, which occurred as early as the 18th century. As a result, the majority of current-day Filipino weddings became predominantly Christian or Catholic[4] in character, which is also because of the mostly Catholic population, although indigenous traditions still exist today in other regions of the Philippines.[4] Parts of Filipino wedding ceremonies have become faith-centered and God-centered, which also highlights the concept that the joining of two individuals is a "life long commitment" of loving and caring.[1][2] In general, the marriage itself does not only signify the union of two persons, but also the fusion of two families, and the unification of two clans.[5]

Requirements

The following are the legal requirements that must be met in order to marry in the Philippines.[6][7] Specific requirements for marriage are detailed in Title I of the Family Code of the Philippines.[8] Some of these requirements are:

- Legal capacity of the contracting parties who must be a male and a female, 18 years old and above without any impediment to get married.[6][7]

- Consent freely given in the presence of the solemnizing officer.

- Authority of the solemnizing officer (only incumbent member of the judiciary; priest, rabbi, imam, or minister of any church or religious sect duly authorized by his church or religious sect and registered with the civil registrar general; ship captain or airplane chief, military commander of a unit to which a chaplain is assigned, in the absence of the latter, during a military operation only in marriages at the point of death; and consul-general, consul or vice-consul only between Filipino citizens abroad are authorized by law to solemnize marriage).[6] Article 35(2) of the Family Code, however, specifies that marriages solemnized by any person not legally authorized to perform marriages which were contracted with either or both parties believing in good faith that the solemnizing officer had the legal authority to do so are neither void nor voidable.[8]

In cases where parental consent or parental advice is needed,[9] marriage law in the Philippines also requires couples to attend a seminar[6] on family planning before the wedding day in order to become responsible for family life and parenthood. The seminar is normally conducted at a city hall or a municipal council.[5]

Some officiating ministers or churches require the couple to present a Certificate of No Marriage Record (CENOMAR), on top of or together with the marriage license and the authority of the solemnizing officer. The CENOMAR can be secured from the Philippine Statistics Authority or its designated sub-offices and branches.[10]

Marriage proposal

The traditional marriage proposal takes the form of the pamanhikan[3] or pamamanhikan or the "parental marriage proposal", a formal way of asking the parents of the woman for her hand. The would-be groom and his parents go to the would-be bride's home, and ask the parents for their consent. Once the woman's parents accept the proposal, other matters will be discussed during this meeting including among other things, the wedding plan, the date, the finances, and the list of guests. The expenses for the wedding are generally shouldered by the groom and his family.[2]

Pamamanhikan enforces the importance of the familial nature of the wedding, as traditionally a marriage is the formation of an alliance between two clans as well as the joining of individuals. This is sometimes further expressed in how the whole extended family goes with the groom and his parents, using the occasion as a chance to meet and greet the other clan. In this situation, there is a feast held at the bride's family home.

This event is separate from the Despedida de Soltera (Spanish: "Farewell to Single-hood") party some families have before the wedding. The local variant of the Hispanic custom normally holds it for the bride, and it is held by her family. It is similar in sentiment to the hen night, albeit a more wholesome and formal version.

Wedding announcement

After the pamamanhikan, the couple performs the pa-alam or "wedding announcement visitations." In this custom, the couple goes to the homes of relatives to inform the latter of their status as a couple and the schedule of their nuptial. It is also during these visits when the couple personally delivers their wedding invitations.[11]

Wedding date and invitation

The typical Filipino wedding invitation contains the date and venue for the wedding ceremony and for the wedding reception, as well as the names and roles of the principal sponsors of the bride. Weddings in the Philippines are commonly held during the month of June.[2]

Ceremonial protocol

Attire

Bride

The bride's attire is typically a custom-made white wedding gown and veil.[1] This is from the Anglo-American influence of dressing the woman in white on her wedding day.[2] A popular alternative is a white version of the Baro't saya, a form of national dress for Filipino women.

Groom

The groom is traditionally clothed in the Barong Tagalog, the formal and traditional transparent, embroidered, button-up shirt made from jusi (also spelled as husi) fabric made from pineapple fibers.[1] This formal Filipino men's dress is worn untucked[12] with a white t-shirt or singlet underneath, and commonly worn together with a black pair of trousers.

Wedding Guests

Males guests typically wear the Filipino Barong, or a suit. Women wear a formal or semi-formal dress, the length and color determined by the wedding theme. [13]

It is discouraged for female guests to wear white since this competes with the bride's traditional wedding dress color. For Filipino-Chinese weddings, it is customary for the bride to wear red. It is frowned upon to wear this color as a guest, for the same reason.

Black and white ensembles are also considered impolite in traditional Filipino-Chinese weddings. These colors symbolize death and mourning, and are deemed to have no places in a festive celebration like weddings. However, using these as accents is acceptable. [14]

Wedding ceremony

Generally, the wedding ceremony proper includes the celebration of an hour-long Mass or religious service. The groom arrives an hour earlier than the bride for the purpose of receiving guests at the church or venue. The groom could be waiting with his parents; the bride will arrive later with her father and mother on board a wedding car. Afterwards, the wedding party assembles to enter the church for the processional.[2] During the nuptials, Catholic and Aglipayan brides customarily bear an ornate, heirloom rosary along with their bridal bouquet.[2]

Ceremonial sponsors, witnesses, and participants

The principal wedding sponsors (also termed "godparents," "special sponsors," "primary sponsors," "counselors," or "witnesses"),[6] are often chosen by the betrothed, sometimes on advice of their families. Multiple pairs of godparents are customary, with six godmothers (ninang) and six godfathers (ninong)

Ritual objects

Ceremonial paraphernalia in Filipino weddings include the arrhae, the candles, the veils, the cord, and wedding rings.[1][2] The ring bearer acts as the holder and keeper of the rings until the exchanging of rings is performed, while the coin bearer acts as the holder and keeper of the arrhae until it is offered and given by the groom to his bride.[2] Among the secondary sponsors or wedding attendants, three pairs – each pair consists of a male and a female secondary sponsor – are chosen to light the wedding candles, handle the veils, and place the cord.[2]

Rings and arrhae

After the exchange of wedding rings by the couple, the groom gives the wedding arrhae to his bride. The arrhae is a symbol of his "monetary gift" to the bride because it is composed of 13 pieces of gold, or silver coins, a "pledge" that the groom is devoted to the welfare and well-being of his wife and future offspring. Both rings and arrhae are blessed first by the priest during the wedding.[2]

Candles

Candle Sponsors are secondary sponsors who light the pair of candles, one on each side of the couple. For Christians, this embodies the presence of God in the union. An old folk belief holds that should one of the candles go out during the rite, the person beside it will die ahead of the other.[3]

Many weddings add the ritual of the "unity candle", which signifies the joining of their two families. The couple takes the two lighted candles and together lights a single candle. For Christians, lighting this single candle symbolises the inclusion of Christ into their life as a married couple.[1][2] The practice is rooted in American Protestantism,[2] and is sometimes discouraged by Catholic parishes for theological reasons.

Veils

After the candle ritual, a pair of secondary sponsors known as the Veil Sponsors will pin the veil(s) on the couple. The veiling ritual signifies the clothing of the two individuals as one.[2]

Two variants of this custom exist: a long, white, rectangular veil is draped over the shoulder of the groom and above the bride's head;[1] two smaller veils may also be pinned on the groom and bride's shoulders.

Cord

After the veiling, the last pair of secondary sponsors will then drape the yugal over the shoulders of the couple. The cord is customarily shaped or looped to form the figure "8" (a lucky number; the figure is also interpreted as the infinity sign), to symbolise "everlasting fidelity."[1][2] Each loop of the cord is placed around the individual collar areas of the bride and the groom.

Apart from silk, popular materials used to make the wedding cord are strings of flowers, links of coins, or a chain designed like a long, double rosary.

Black Bible

Catholic and Protestant weddings include the entrustment to the couple of a copy of the Holy Bible.

Wedding reception

During the wedding reception, it is typical to release a pair of white male and female doves, symbolising marital harmony and peace.[1] These are placed in a cage or receptacle, which can be opened by pulling ribbons or cords or manually opened and released by the couple themselves. After their release from their cage,[1] the person who catches them may take them home to rear as pets.

It is also a common practice to have the "Money Dance." This is where the bride and groom dance to slow music while the guests pin money (notes) on the couple.[13] The monetary gift from the dance is a way to help the new couple get started with their married life.

Tossing the bouquet is for the most part uncommon for the bride to do, though it is increasingly being observed by younger women. Instead, the bride traditionally offers it at a side altar of the church before an image of either the Blessed Virgin Mary or a patron saint, or offers it at the grave of an important relative or ancestor.[2]

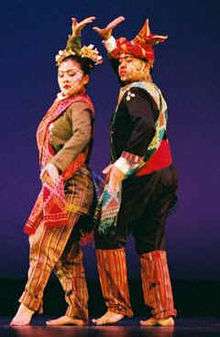

Filipino Muslim wedding

Filipino Muslims in the Mindanao region of the Philippines commonly practice pre-arranged marriages and betrothal.[15] The Tausog people's wedding include the pangalay, a celebration or announcement performed by means of the playing of percussion instruments like as the gabbang, the kulintang, and the agong. Included in the wedding ceremony that is officiated by an Imam are readings taken from the Qur'an and the placement of the groom's fingerprint on the forehead of the bride.

Same sex marriage

Marriage between couples of the same sex is currently not possible under the laws of the Philippines because, according to the Filipino Family Code, both family and marriage are considered as heterosexual units. The legal concept of a family in the Philippines does not incorporate homosexual relationships. Furthermore, finding that a party to the marital union is either homosexual or lesbian is a ground for annulment of the marriage and legal separation in the Philippines, which leads to the severance of the homosexual individual's spousal inheritance, claims to any conjugal property, and the custody of offspring.[16]

Pre-colonial Wedding customs

Filipinos have pre-colonial customs based on the Indian Hindu wedding that are related to marriage and weddings and still carried out even after colonial masters destroyed other customs after the imposition of Christianity.[3][4]

Pre-colonial customs include the groom or bride avoiding travel beforehand to prevent accidents from happening.[3] The bride must not wear pearls as these are similar to tears,[3] and a procession of men holding bolos and musicians playing agongs must be done. This march was also done after the ceremony until the newly-wed couple reaches their abode. The purpose of this procession is similar to the current practise of breaking plates during the wedding reception, in order to dispel bad luck.[3][4]

Spanish colonisers introduced new beliefs to the Philippines, with particular concern over banning activities that may cause broken marriages, sadness and regret. Wedding gowns cannot be worn in advance, [3] as any black-coloured clothing during the ceremony, and sharp objects such as knives cannot be given as gifts.[3][4]

Other beliefs include a typhoon on the wedding day being an ill omen; that after the ceremony the bride should walk ahead of her husband or step on his foot to prevent being dominated by him; and an accidentally dropped ring, veil, or arrhae will cause marital misery.[4][17]

Superstitious beliefs on good fortune include showering the married couple with uncooked rice, as this wishes them a prosperous life together.[3] The groom's arrival at the venue ahead of his bride also diminishes dire fate.[3] In addition, a single woman who will follow the footsteps of a newly married couple may enhance her opportunity to become a bride herself.[4]

Siblings are not permitted to marry within the calendar year as this is considered bad luck. The remedy to this belief, called sukob, is to have the one marrying later pass through the back entrance of the church instead of its main doors. Bride and groom cannot have marital relations starting from the 60th day prior to the wedding.

See also

- Religion in the Philippines

- Sexuality in the Philippines

- Civil Code of the Philippines

- Philippine legal codes

- LGBT culture in the Philippines

- LGBT rights in the Philippines

- Christian views on marriage

- Catholic marriage

- Marriage and wedding customs in Islam

- Islamic marital jurisprudence

References

Specific

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Wedding in the Philippines, Tagaytay Wedding Cafe Blog, www.tagaytayweddingcafe.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Wedding planning: Filipino Wedding Traditions Archived 2010-02-11 at the Wayback Machine., Information on the characteristics of a traditional Filipino Wedding, www.essortment.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Philippine Wedding Culture and Superstitions, asiarecipe.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Funtecha, Henry F. IIlonggo Traditional Marriage Practices (2), Bridging the Gap, The News Today, thenewstoday.info, June 23, 2006.

- 1 2 Daza, Jullie Y. "I Went to Your Wedding", High Profile, The Magazine of PAGCOR (Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation), Issue 3, Fall 2009, page 82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stritof, Sheri and Bob Stritof. Philippines Marriage License Information, Getting Married in The Republic of The Philippines, About.com Guide, marriage.about.com

- 1 2 Stritof, Sheri and Bob Stritof. Philippine Marriage License Information, About.com Guide, marriage.about.com

- 1 2 3 "The Family Code of the Philippines". Chan Robles Law Library. July 6, 1987.

- ↑ Article 16 of the Family Code.[8]

- ↑ CENOMAR Archived 2010-03-15 at the Wayback Machine. from Weddings at Work (W@W). Retrieved on 4 March 2010, 14:54

- ↑ Pa-alam or the Wedding Announcement, Filipino Wedding Traditions and Spanish Influence, muslim-marriage-guide.com

- ↑ Barong Tagalog, philippines.hvu.nl

- 1 2 Network, Asia Wedding. "Asia Wedding Magazine".

- ↑ Network, Asia Wedding. "Asia Wedding Magazine".

- ↑ Courtship in the Philippines Today, SarahGats's Blog, sarahgats.wordpress.com, March 29, 2009

- ↑ Hunt, Dee Dicen and Cora Sta. Ana-Gatbonton. Filipino Sexuality, Filipino Women and Sexual Violence: Speaking Out and Providing Services, cpcabrisbane.org

- ↑ "Maui Weddings". www.justmauiweddings.com.

General

- Wedding Traditions in the Philippine Islands, worldweddingtraditions.com

- Filipino Wedding Ceremony Traditions, mybarong.com

- Filipino Weddings, snoopydude.com

- Filipino Weddings, blissweddings.com

- Weddings in the Philippines, weddingphilippines.net

- Weddings in the Philippines (HTML), seiyaku.com

- Weddings in the Philippines (PDF), seiyaku.com

- Maranao Wedding of the Year, Inquirer Philippines, showbizstyle.inquirer.net

External links

- Filipino Wedding Ceremonies, videobabylon.ca

- Kasalan Culture, weddingsatwork.com

- My Filipino Wedding, myfilipinowedding.com

- Marriage Rites, Customs and Ceremonies of the Nations of the Universe Book, site.booksite.com

- Ways to Keep Romantic Wedding on a Budget