Marinid dynasty

| Marinid dynasty | ||||||||||

| ⵉⵎⵔⵉⵏⴻⵏ Imrinen (ber) المرينيون Al Marīniyūn (ar) | ||||||||||

| Ruling dynasty of Morocco[1][2] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

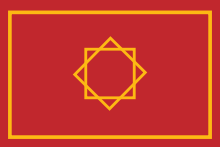

Flag

Emblem

| ||||||||||

The Marinid realm at its maximal extent (1347–1348) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Fes | |||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | |||||||||

| Government | Sultanate | |||||||||

| Sultan | ||||||||||

| • | 1215–1217 | Abd al-Haqq I | ||||||||

| • | 1420–1465 | Abd al-Haqq II | ||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Established | 1244 | ||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1465 | ||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Banu Abd al-Haqq | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country |

|

| Parent house | Banu Marin |

| Titles | Sultan of Morocco |

| Style(s) | Amir al-Muslimin |

| Founded | 1215 |

| Founder | Abd al-Haqq I |

| Final ruler | Abd al-Haqq II |

| Current head | none |

| Deposition | 1465 |

| Cadet branches |

Wattasid dynasty Ouartajin dynasty |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Morocco |

|

|

Related topics

|

|

|

The Marinid dynasty (Berber: Imrinen, Arabic: Marīniyūn) or Banu abd al-Haqq was a Sunni Muslim[3] dynasty of Zenata Berber descent that ruled Morocco from the 13th to the 15th century.[1][4]

In 1244, the Marinids overthrew the Almohad dynasty, which controlled Morocco.[5] The Marinid dynasty briefly held sway over all the Maghreb in the mid-14th century. It supported the Kingdom of Granada in Al-Andalus in the 13th and 14th centuries; an attempt to gain a direct foothold on the European side of the Strait of Gibraltar was however defeated at the Battle of Río Salado in 1340 and finished after the Castilian conquest of Algeciras from the Marinids in 1344.[6]

The Marinids were overthrown after the 1465 revolt. The Wattasids, a related dynasty, came to power in 1472.

History

Origins

The Marinids were a branch of the Wassin,[7] a nomadic Zenata Berber tribe that lived in the Zibans (present-day Algeria) before being driven towards Tlemcen by the Arab invasion in the 11th century.[8]

The tribe had first frequented the area between Sijilmasa and Figuig, Morocco.[9] Following the arrival of Arab tribes in the area in the 11th-12th centuries, Marinids moved to the north-west of present-day Algeria,[9] before settling into northern Morocco by the beginning of the 13th century.[10]

The Marinids took their name from their ancestor, Marin ibn Wartajan al-Zenati.[11]

Rise

After arriving in Morocco, they initially submitted to the Almohad dynasty, which was at the time the ruling house. After successfully contributing to the Battle of Alarcos, in central Spain, the tribe started to assert itself as a political power.[12] Starting in 1213, they began to tax farming communities of north-eastern Morocco (the area between Nador and Berkane). The relationship between them and the Almohads became strained and starting in 1215, there were regular outbreaks of fighting between the two parties. In 1217 they tried to occupy eastern Morocco, but they were expelled, after which they pulled back and settled in the eastern Rif mountains. Here they remained for nearly 30 years. During their stay in the Rif, the Almohad state suffered huge blows, losing large territories to the Christians in Spain, while the Hafsids of Ifriqia broke away in 1229, followed by the Zayyanid dynasty of Tlemcen in 1235.

Between 1244 and 1248 the Marinids were able to take Taza, Rabat, Salé, Meknes and Fes from the weakened Almohads.[13] The Marinid leadership installed in Fes declared war on the Almohads, fighting with the aid of Christian mercenaries. Abu Yusuf Yaqub (1259–1286) captured Marrakech in 1269.[14]

Height

After the Nasrids ceded Algeciras to the Marinids, Abu Yusuf went to Al-Andalus to support the ongoing struggle against the Kingdom of Castile. The Marinid dynasty then tried to extend its control to include the commercial traffic of the Strait of Gibraltar.

It was in this period that the Spanish Christians were first able to take the fighting to Morocco: in 1260 and 1267 they attempted an invasion of Morocco, but both attempts were defeated. After gaining a foothold in Spain, the Marinids became active in the conflict between Muslims and Christians in Iberia. To gain absolute control of the trade in the Strait of Gibraltar, from their base at Algeciras they started the conquest of several Spanish towns: by the year 1294 they had occupied Rota, Tarifa and Gibraltar.

In 1276 they founded Fes Jdid, which they made their administrative and military centre. While Fes had been a prosperous city throughout the Almohad period, even becoming the largest city in the world during that time,[15] it was in the Marinid period that Fes reached its golden age, a period which marked the beginning of an official, historical narrative for the city.[16][17] It is from the Marinid period that Fes' reputation as an important intellectual centre largely dates, they established the first madrassas in the city and country.[18][19][20] The principal monuments in the medina, the residences and public buildings, date from the Marinid period.[21]

Despte internal infighting, Abu Said Uthman II (1310–1331) initiated huge construction projects across Morocco. Several madrassas were built, the Al-Attarine Madrasa being the most famous. The building of these madrassas were necessary to create a dependent bureaucratic class, in order to undermine the marabouts and Sharifian elements in Morocco.

The Marinids also strongly influenced the policy of the Emirate of Granada, from which they enlarged their army in 1275. In the 13th century, the Kingdom of Castile made several incursions into Morocco. In 1260, Castilian forces raided Salé and, in 1267, initiated a full-scale invasion of Morocco, but the Marinids repelled them.

At the height of their power, during the rule of Abu al-Hasan 'Ali (1331–1348), the Marinid army was large and disciplined. It consisted of 40.000 Zenata cavalry, while Arab nomads contributed to the cavalry and Andalusians were included as archers. The personal bodyguard of the sultan consisted of 7.000 men, and included Christian, Kurdish and Black African elements.[12] Under Abu al-Hasan another attempt was made to reunite the Maghreb. In 1337 the Abdalwadid kingdom of Tlemcen was conquered, followed in 1347 by the defeat of the Hafsid empire in Ifriqiya, which made him master of a huge territory, which spanned from southern Morocco to Tripoli. However, in 1340 the Marinids suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of a Portuguese-Castilian coalition in the Battle of Río Salado, and finally had to withdraw from Andalusia, only holding on to Algeciras. In that same year a revolt of Arab tribes in southern Tunisia, made them lose their eastern territories.

In 1348 Abu al-Hasan was deposed by his son Abu Inan Faris, who tried to reconquer Algeria and Tunisia. Despite several successes, he was strangled by his own vizir in 1358, after which the dynasty began to decline.

Decline

After the death of Abu Inan Faris in 1358, the real power lay with the viziers, while the Marinid sultans were paraded and forced to succeed each other in quick succession. The county was divided and political anarchy set in, with different viziers and foreign powers supporting different factions. In 1359 Hintata tribesmen from the High Atlas came down and occupied Marakesh, capital of their Almohad ancestors, which they would govern independently until 1526. To the south of Marakesh, Sufi mystics claimed autonomy, and in the 1370s Azemmour broke off under a coalition of merchants and Arab clan leaders of the Banu Sabih. To the east, the Zianid and Hafsid families reemerged and to the north, the Europeans were taking advantage of the Moroccan instability by attacking the Moroccan coast. Meanwhile, unruly wandering Arab Bedouin tribes increasingly spread anarchy in Morocco, which accelerated the decline of the empire.

In the 15th century Morocco was hit by a financial crisis, after which the state had to stop financing the different marabouts and Sharifian families, which had previously been useful instruments in controlling the country. The political support of these marabouts and Sharifians halted, and Morocco splintered into different entities. In 1399 Tetouan was taken and its population was massacred and in 1415 the Portuguese captured Ceuta. After the sultan Abdalhaqq II (1421–1465) tried to break the power of the Wattasids, he was executed.

Marinid rulers after 1420 came under the control of the Wattasids, who exercised a regency as Abd al-Haqq II became Sultan one year after his birth. The Wattasids however refused to give up the Regency after Abd al-Haqq came to age.[22]

In 1459, Abd al-Haqq II managed a massacre of the Wattasid family, breaking their power. His reign, however, brutally ended as he was murdered during the 1465 revolt.[23] This event saw the end of the Marinid dynasty as Muhammad ibn Ali Amrani-Joutey, leader of the Sharifs, was proclaimed Sultan in Fes. He was in turn overthrown in 1471 by Abu Abd Allah al-Sheikh Muhammad ibn Yahya, one of the two the surviving Wattasids from the 1459 massacre, who instigated the Wattasid dynasty.

Chronology of events

- 1215: The Banu Marin (Marinids) attacks the Almohads when the 16-year-old Almohad caliph Yusuf II Al-Mustansir comes to power in 1213. The battle takes place on the coast of the Rif. In the reign of Yusuf II Al-Mustansir a great tower is erected to protect the royal palace in Seville.[24]

- 1217: Abd al-Haqq I dies during victorious combat against the Almohads. His son Uthman ibn Abd al-Haqq (Uthman I) succeeds to the throne. Marinids take possession of the Rif and seem to want to remain there. The Almohades counterattack in vain.

- 1240: Uthman I is assassinated by one of his Christian slaves. His brother Muhammad ibn Abd Al-Haqq (Muhammad I) succeeds him.

- 1244: Muhammad I is killed by an officer of his own Christian mercenary militia. Abu Yahya ibn Abd al-Haqq, the third son of Abd Al-Haqq, succeeds him.

- 1249: Severe repression of anti-Marinid forces in Fes.

- 1258: Abu Yahya ibn Abd al-Haqq dies of disease. His uncle, Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn Abd Al-Haqq, fourth son of Abd Al-Haqq, succeeds to the throne.

- 1260: The Castilians raid Salé.

- 1269: Seizure of Marrakesh and the end of Almohad domination of the western Maghreb.

- 1274: The Marinids seize Sijilmassa.

- 1276: Founding of Fes Jdid ("New Fes"), a new city near Fes, which comes to be considered a new district of Fes, in contrast to Fes el Bali ("Old Fes").

- 1286: Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn Abd Al-Haqq dies of disease in Algeciras after a fourth expedition to the Iberian Peninsula. His son Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr replaces him.

- 1286: Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr combats revolts in and around the Draa River and the province of Marrakesh.

- 1288: Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr receives in Fes the envoys of the king of Granada, to whom the town of Cadiz is returned.

- 1291: Construction of the mosque of Taza, the earliest preserved Marinid building.

- 1296: Construction of Sidi Boumediene mosque, or Sidi Belhasan, in Tlemcen.

- 1299: Beginning of Tlemcen's siege by the Marinids, which will last nine years.

- 1306: Conquest and destruction of Taroudannt.

- 1307: Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr is assassinated by a eunuch in connection with some obscure matter related to the harem. His son Abu Thabit Amir succeeds to the throne.

- 1308: Abu Thabit dies of disease after only one year in power in Tetouan, a city which he has just founded. His brother, Abu al-Rabi Sulayman succeeds him.

- 1309: Abu al-Rabi Sulayman enters Ceuta.

- 1310: Abu al-Rabi dies of disease after having repressed a revolt of army officials in Taza. Among them is Gonzalve, chief of the Christian militia. His brother Abu Said Uthman succeeds him to the throne.

- 1323: Construction of the Attarin's madrassa in Fes.

- 1325: Ibn Battuta begins his 29-year journey across Africa and Eurasia.

- 1329: The Marinids defeat the Castilians in Algeciras, establishing a foothold in the south of the Iberian peninsula with the hope of reversing the Reconquista.

- 1331: Abu Said Uthman dies. His son Abu al-Hasan ibn Uthman succeeds him.

- 1337: First occupation of Tlemcen.

- 1340: A combined Portuguese–Castilian army defeats the Marinids in the Battle of Rio Salado, close to Tarifa, the southernmost town of the Iberian peninsula. The Marinids return to Africa.

- 1344: The Castilians take over Algeciras. The Marinids are ejected from Iberia.

- 1347: Abu al-Hasan ibn Uthman destroys the Hafsid dynasty of Tunis and restores his authority over all the Maghreb.

- 1348: Abu al-Hasan dies, his son Abu Inan Faris succeeds him as Marinid ruler.

- 1348: The Black Death and the rebellions of Tlemcen and Tunis mark the beginning of the decline of the Marinids, who are unable to drive back the Portuguese and the Castilians.

- 1350: Construction of Bou Inania's madrassa in Meknes.

- 1351: Second seizure of Tlemcen.

- 1357: Defeat of Abu Inan Faris in front of Tlemcen. Construction of another of Bou Inania's madrassas in Fes.

- 1358 Abu Inan is assassinated by his vizir. A time of confusion starts. Each vizir tries to install weak candidates on the throne.

- 1358: Abu Zian as-Said Muhammad ibn Faris is named sultan by the vizirs, just after the assassination of Abu Inan. His reign lasts only a few months. Abu Yahya abu Bakr ibn Faris comes to power, but also reigns only a few months.

- 1359: Abu Salim Ibrahim is nominated sultan by the vizirs. He is one of the sons of Abu al-Hasan ibn Uthman and is supported by the king of Castille, Pedro.

- 1359: Resurgence of the Zianids of Tlemcen.

- 1361: Abu Umar Tachfin is named the successor to Abu Salim Ibrahim by the vizirs, with the support of the Christian militia. He reigns only a few months.

- 1361: The period called the "reign of the vizirs" ends.

- 1362: Muhammad ibn Yaqub assumes power. He is a young son of Abu al-Hasan ibn Uthman, who had taken refuge in Castile.

- 1366: Muhammad ibn Yaqub is assassinated by his vizir. He is replaced by Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz ibn Ali, one of the sons of Abu al-Hasan ibn Uthman who until this time had been held locked up in the palace of Fes.

- 1370: Third seizure of Tlemcen.

- 1372: Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz ibn Ali dies of disease leaving the throne to his very young son Muhammad as-Said, beginning a new period of instability. The vizirs try on several occasions to install a puppet sovereign.

- 1373: Muhammad as-Said is presented as the heir to his father, Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz ibn Ali, but being only five years old cannot reign, and dies in the same year.

- 1374: Abu al-Abbas Ahmad, supported by the Nasrid princes of Granada, takes power.

- 1374: Partition of the empire into two kingdoms: the Kingdom of Fes and the Kingdom of Marrakech.

- 1384: Abu al-Abbas is temporarily removed by the Nasrids. The Nasrids replace him with Abu Faris Musa ibn Faris, a disabled son of Abu Inan Faris. This ensures a kind of interim during the reign of Abu al-Abbas Ahmad from 1384 to 1386.

- 1384: Abu Zayd Abd ar-Rahman reigns over the Kingdom of Marrakech from 1384 to 1387 while the Marinid throne is still based in Fes.

- 1386: Al-Wathiq ensures the second part of the interim in the reign of Abu al-Abbas from 1386 to 1387.

- 1387: Abu Al-Abbas begins to give vizirs more power. Morocco knows six years of peace again, although Abu Al-Abbas benefits from this period to reconquer Tlemcen and Algiers.

- 1393: Abu Al-Abbas dies. Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz ibn Ahmad is designated as the new sultan. The troubles which follow the sudden death of Abu Al-Abbas in Taza make it possible for the Christian sovereigns to carry the war into Morocco.

- 1396: Abu Amir Abdallah succeeds to the throne.

- 1398: Abu Amir dies. His brother, Abu Said Uthman ibn Ahmad, takes power.

- 1399: Benefitting from the anarchy within the Marinid kingdom, king Henry III of Castile arrives in Morocco, seizes Tetouan, massacres half of the population and reduces the rest to slavery.

- 1415: King John I of Portugal seizes Ceuta. This conquest marks the beginning of overseas European expansion.

- 1418: Abu Said Uthman besieges Ceuta but is defeated.

- 1420: Abu Said Uthman dies. He is replaced by his son, Abu Muhammad Abd al-Haqq, who is only one year old.

- 1437: Failure of a Portuguese expedition to Tangier. Many prisoners are taken and the infant Fernando, the Saint Prince is kept as a hostage. A treaty is made with the Portuguese enabling them to embark if they return Ceuta. Fernando is kept as a hostage to guarantee the execution of this pact. Influenced by Pope Eugene IV, Edward of Portugal sacrifices his brother for national trade interests.

- 1458: King Afonso V of Portugal prepares an army for a crusade against the Ottomans in response to the call of Pope Pius II, but he instead uses the army to attack a small port located between Tangier and Ceuta.

- 1459: Abu Muhammad Abd Al-Haqq revolts against his own Wattasid vizirs. Only two brothers survive, who will become the first Wattasid sultans in 1472.

- 1462: Ferdinand IV of Castile takes over Gibraltar.

- 1465: Abu Muhammad Abd Al-Haqq appoints a Jewish vizir, Aaron ben Batash, provoking a popular revolt. The sultan dies in the revolt when his throat is cut. The Portuguese king Afonso V finally manages to take Tangier, benefitting from the troubles in Fes.

- 1472: Abu Abd Allah al-Sheikh Muhammad ibn Yahya, one of the two Wattasid vizirs surviving the 1459 massacre, installs himself in Fes, where he founds the Wattasid dynasty.

Marinid rulers

- 1215–1269 : leaders of the Marinids, engaged in a struggle against the Almohads, based in Taza from 1216 to 1244

- Abd al-Haqq I (1215–1217)

- Uthman I (1217–1240)

- Muhammad I (1240–1244)

- Since 1244 : Marinid Emirs based in Fez

- Abu Yahya ibn Abd al-Haqq (1244–1258)

- Umar (1258–1259)

- Abu Yusuf Yaqub (1259–1269)

- 1269–1465 : Marinid Sultans of Fez and Morocco

- Abu Yusuf Yaqub (1269–1286)

- Abu Yaqub Yusuf (1286–1306)

- Abu Thabit Amir (1307–1308)

- Abu al-Rabi Sulayman (1308–1310)

- Abu Said Uthman II (1310–1331)

- Abu al-Hasan 'Ali (1331–1348)

- Abu Inan Faris (1348–1358)

- Muhammad II as Said (1359)

- Abu Salim Ali II (1359–1361)

- Abu Umar Tashfin (1361)

- Abu Zayyan Muhammad III (1362–1366)

- Abu l-Fariz Abdul Aziz I (1366–1372)

- Muhammad as-Saîd (1372–1374)

- Abu l-Abbas Ahmad (1374–1384)

- Abu Zayyan Muhammad IV (1384–1386)

- Muhammad V (1386–1387)

- Abu l-Abbas Ahmad (1387–1393)

- Abdul Aziz II (1393–1398)

- Abdullah (1398–1399)

- Abu Said Uthman III (1399–1420)

- Abd al-Haqq II (1420–1465)

See also

References

- 1 2 "Marinid dynasty (Berber dynasty) - Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "Marinides ou Mérinides ; Dynastie marocaine (1269-1465) - Encyclopédie Larousse en ligne". Larousse.fr. Retrieved 2016-06-05.

- ↑ Ira M. Lapidus, Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History, (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 414.

- ↑ C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, (Columbia University Press, 1996), 41-42.

- ↑ (in French)"Les Merinides" on Universalis

- ↑ Niane, D.T. (1981). General History of Africa. IV. p. 91. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ Abd al-Rahman b. Muhammad Ibn Khaldûn (1856). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale, tr. par le baron de Slane. p. 25.

- ↑ V. Piquet, Les civilisations de l'Afrique du nord: Berbères-Arabes Turcs, Ed. Colin, 1909

- 1 2 C.E. Bosworth. The Encyclopaedia of Islam: Vol 4. Brill Archives. p. 571.

- ↑ Yassir Benhima, Les Mérinides et les Wattasides (1196-1549), on qantara-med.org

- ↑ Idris El Hareir (2011). The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. UNESCO. p. 420. ISBN 9789231041532.

- 1 2 The Encyclopedia of Islam, Volume 6, Fascicules 107-108 - Clifford Edmund Bosworth - Google Boeken. Books.google.nl. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "Encyclopédie Larousse en ligne - Marinides ou Mérinides". Larousse.fr. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, 42.

- ↑ The Report: Morocco 2009 - Oxford Business Group - Google Boeken. Books.google.nl. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "An Architectural Investigation of Marrind and Wattasid Fes Medina (674-961/1276-1554), In Terms of Gender, Legend, and Law" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Watasid Fes" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. p. 23. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936 - Google Boeken. Books.google.nl. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ The Berbers and the Islamic State - Maya Shatzmiller - Google Boeken. Books.google.nl. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ Islamic Art and Visual Culture: An Anthology of Sources - Google Boeken. Books.google.nl. 2011-04-25. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "Al- Hakawati". Al-hakawati.net. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ Julien, Charles-André, Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord, des origines à 1830, Payot 1931, p.196

- ↑ C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic dynasties, p.42 Edinburgh University Press 1996. ISBN 978-0-231-10714-3.

- ↑ E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, M. Th Houtsma

Bibliography

- JULIEN, Charles-André, Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord, des origines à 1830, édition originale 1931, réédition Payot, Paris, 1994 (in French)

- Marinid Dynasty at britannica

| — Royal house — Banu Marin | ||

| Preceded by Almohad dynasty |

Ruling house of Morocco 1269–1465 |

Succeeded by Idrisid dynasty Joutey branch |