Brazilian Navy

The Brazilian Navy (Portuguese: Marinha do Brasil) is the naval service branch of the Brazilian Armed Forces, responsible for conducting naval operations. The Brazilian Navy is the largest navy in South America and in Latin America, and the second largest navy in the Americas, after the United States Navy.[2]

The navy was involved in Brazil's war of independence from Portugal. Most of Portugal's naval forces and bases in South America were transferred to the newly independent country. In the initial decades following independence, the country maintained a large naval force and the navy was later involved in the Cisplatine War, the River Plate conflicts, the Paraguayan War as well as other sporadic rebellions that marked Brazilian history.

By the 1880s the Brazilian Imperial Navy was the most powerful in South America. After the 1893 naval rebellion, there was a hiatus in the development of the navy until 1905, when Brazil acquired two of the most powerful and advanced dreadnoughts of the day which sparked dreadnought race with Brazil's South American neighbours. The Brazilian Navy participated in both World War I and World War II, engaging in anti-submarine patrols in the Atlantic.

The Brazilian Navy's tonnage consists of French-made attack aircraft carrier (CVA), British-built guided missile frigates (FFG), locally built corvettes (FFL), coastal diesel-electric submarines (SSK) and many other river and coastal patrol craft, among other vehicles.

Mission

In addition to the roles of a traditional navy, the Brazilian Navy also carries out the role of organizing the merchant navy and other operational safety missions traditionally conducted by a coast guard. Other roles include:

- Conducting national maritime policy

- Implementing and enforcing laws and regulations with respect to the sea and inland waters.

History

Origins

The origins of the Brazilian Navy date back to the Portuguese naval forces based in Brazil. The transfer of the Portuguese monarchy to Brazil in 1808 during the Napoleonic wars also resulted in the transfer of a large part of the structure, personnel and ships of the Portuguese Navy. These became the core of the Navy of Brazil.

Imperial Navy (1822–1889)

War of Independence

The Brazilian Navy came into being with the independence of the country. Some of its members were native-born Brazilians, who under Portuguese rule had been forbidden to serve, while other members were Portuguese born who adhered to the cause of independence and foreign mercenaries. A number of establishments previously created by King João VI of Portugal were incorporated into the navy such as the Department of Navy, Headquarters of the Navy, the Intendancy and Accounting Department, the Arsenal (Shipyard) of the Navy, the Academy of Navy Guards, the Naval Hospital, the Auditorship, the Supreme Military Council, the powder plant, and others. The Brazilian-born Captain Luís da Cunha Moreira was chosen as the first minister of the Navy on October 28, 1822.[3][4]

British naval officer Lord Thomas Alexander Cochrane was made the commander of the Brazilian Navy and received the rank of "First Admiral".[5][6] At that time, the fleet was composed of one ship of the line, four frigates, and smaller ships for a total of 38 warships. The Secretary of Treasury Martim Francisco Ribeiro de Andrada created a national subscription to generate capital in order to increase the size of the fleet. Contributions were sent from all over Brazil. Even Emperor Pedro I acquired a merchant brig at his own expense (renamed Caboclo) and donated it to the Navy.[6][7] The navy fought in the north and also south of Brazil where it had a decisive role in the independence of the country.[8] After the suppression of the revolt in Pernambuco in 1824 and prior to the Cisplatine War, the navy increased significantly in size and strength. Starting with 38 ships in 1822, eventually the navy had 96 modern warships of various types with over 690 cannons.

Cisplatine War and rebellions (1825–49)

Example of vessels commissioned during this period:

Escuna Bertioga, 1825

Escuna Bertioga, 1825 Frigate Amalia, 1843

Frigate Amalia, 1843 Steam Corvette Dom Afonso, 1850

Steam Corvette Dom Afonso, 1850

The Navy blocked the estuary of the Río de la Plata hindering the contact of the United Provinces (as Argentina was then called) with the Cisplatine rebels who wanted Uruguay to joined Argentina again or become an independent country, and the outside world. Several battles had occurred between Brazilian and Argentine ships until the defeat of an Argentine flotilla composed of two corvettes, five brigs and one barquentine near the Island of Santiago in 1827. Brazil lost the war and in 1828 had to accept the independence of Uruguay. When Pedro I abdicated in 1831, he left a powerful navy made up of two ships of the line and ten frigates in addition to corvettes, steamships, and other ships for a total of at least 80 warships in peace time.[9][10]

During the 58-year reign of Pedro II the Brazilian Navy achieved its greatest strength in relation to navies around the world.[11] The Arsenal, Navy department, and the Naval Jail were improved and the Imperial Marine Corps was created. Steam navigation was adopted. Brazil quickly modernized its fleet acquiring ships from foreign sources while also constructing ships locally. Brazil's Navy substituted the old smoothbore cannons for new ones with rifled barrels, which were more accurate and had longer ranges. Improvements were also made in the Arsenals (shipyards) and naval bases, which were equipped with new workshops.[12] Ships were constructed in the Naval Arsenal of Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Recife, Santos, Niterói and Pelotas. The Navy also successfully fought against all revolts that occurred during the Regency where it conducted blockades and transported the Army troops; including Cabanagem, Ragamuffin War, Sabinada, Balaiada, amongst others.[12][13]

When Emperor Pedro II was declared of legal age and assumed his constitutional prerogatives in 1840, the Armada had over 90 warships: six frigates, seven corvettes, two barque-schooners, six brigs, eight brig-schooners, 16 gunboats, 12 schooners, seven armed brigantine-schooners, six steam barques, three transport ships, two armed luggers, two cutters and thirteen larger boats.[14]

During the 1850s the State Secretary, the Accounting Department of the Navy, the Headquarters of the Navy and the Naval Academy were reorganized and improved. New ships were purchased and the ports administrations were better equipped. The Imperial Mariner Corps was definitively regularized and the Marine Corps was created, taking the place of the Naval Artillery. The Service of Assistance for Invalids was also established, along with several schools for sailors and craftsmen.[15]

Platine & Paraguayan wars (1849–70)

Example of vessels commissioned during this period:

Steam gunboat Ivahy, attack on Paraguayan Forts in 1867.

Steam gunboat Ivahy, attack on Paraguayan Forts in 1867. Steam Frigate Recife, 1850.

Steam Frigate Recife, 1850. Steam Corvetta Parnahyba, 1860.

Steam Corvetta Parnahyba, 1860. Ironclad Tamandare, 1865.

Ironclad Tamandare, 1865.- Ironclad Bahia, 1865.

Ironclad Colombo, 1865.

Ironclad Colombo, 1865..jpg) Ironclad Barroso during the Battle of Curuzú in 1866.

Ironclad Barroso during the Battle of Curuzú in 1866. Ironclad Brasil seriously damaged after the attack on the Curuzú Fort, 1866.

Ironclad Brasil seriously damaged after the attack on the Curuzú Fort, 1866. Steam frigate Amazonas, 1870.

Steam frigate Amazonas, 1870.

The conflicts in the Platine region did not cease after the war of 1825. The anarchy caused by the despotic Rosas and his desire to subdue Bolívia, Uruguay and Paraguay forced Brazil to intercede. The Brazilian Government sent a naval force of 17 warships (a ship of the line, 10 corvettes and six steamships) commanded by the veteran John Pascoe Grenfell.[16] The Brazilian fleet succeeded in passing through the Argentine line of defence at the Tonelero Pass under heavy attack and transported the troops to the theater of operations. The Brazilian Armada had a total of 59 vessels of various types in 1851: 36 armed sailing ships, 10 armed steamships, seven unarmed sailing ships and six sailing transports.[17]

More than a decade later the Armada was once again modernized and its fleet of old sailing ships was converted to a fleet of 40 steamships armed with more than 250 cannons.[18] In 1864 the navy fought in the Uruguayan War and immediately afterwards in the Paraguayan War where it annihilated the Paraguayan navy in the Battle of Riachuelo. The navy was further augmented with the acquisition of 20 ironclads and six fluvial monitors. At least 9,177 navy personnel fought in the five years' conflict.[19] Brazilian naval constructors such as Napoleão Level, Trajano de Carvalho and João Cândido Brasil planned new concepts for warships that allowed the country's Arsenals to retain their competitiveness with other nations.[20] All damage suffered by ships was repaired and various improvements were made to them.[21] In 1870, Brazil had 94 modern warships[22] and had the fifth most powerful navy in the world.[23]

Expansion and the end of the Empire (1870–89)

Example of vessels commissioned during this period:

Ironclad Sete de Setembro, 1874.

Ironclad Sete de Setembro, 1874. Cruiser Almirante Barroso, 1880.

Cruiser Almirante Barroso, 1880. Battleship Riachuelo, 1885.

Battleship Riachuelo, 1885..jpg) Cruiser Imperial Marinheiro, 1882.

Cruiser Imperial Marinheiro, 1882. Battleship Aquidabã, 1893.

Battleship Aquidabã, 1893. Light cruiser Pereira da Cunha, 1890.

Light cruiser Pereira da Cunha, 1890..jpg) Torpedo boat Tiradentes, 1893.

Torpedo boat Tiradentes, 1893.

During the 1870s, the Brazilian Government strengthened the navy as the possibility of a war against Argentina over Paraguay's future became quite real. Thus, it acquired a gunboat and a corvette in 1873; an ironclad and a monitor in 1874; and immediately afterwards two cruisers and another monitor.[8][24] The improvement of the Armada continued during the 1880s. The Arsenals of the Navy in the provinces of Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, Pernambuco, Pará and Mato Grosso continued to build dozens of warships. Also, four torpedo boats were purchased.[25]

On November 30, 1883, the Practical School of Torpedoes was created along with a workshop devoted to constructing and repairing torpedoes and electric devices in the Arsenal of Navy of Rio de Janeiro.[26] This Arsenal constructed four steam gunboats and one schooner, all with iron and steel hulls (the first of these categories constructed in the country).[25] The Imperial Armada reached its apex with the incorporation of the ironclad battleships Riachuelo and Aquidabã (both equipped with torpedo launchers) in 1884 and 1885, respectively. Both ships (considered state-of-the-art by experts from Europe) allowed the Brazilian Armada to retain its position as one of the most powerful naval forces.[27] By 1889, the navy had 60 warships[21] and was the fifth or sixth most powerful navy in the world.[28]

In the last cabinet of the monarchic regime, the Minister of the Navy, Admiral José da Costa Azevedo (the Baron of Ladário), left the reorganization and modernization of the navy unfinished.[21] The coup that ended the monarchy in Brazil in 1889 was not well accepted by the Armada. Imperial Mariners were attacked when they tried to support the imprisoned Emperor in the City Palace. The Marquis of Tamandaré begged Pedro II to allow him to fight back the coup; however, the Emperor refused to allow any bloodshed.[29] Tamandaré would later be imprisoned by order of the dictator Floriano Peixoto under the accusation of financing the monarchist military in the Federalist Revolution.[30]

The Baron of Ladário remained in contact with the exiled Imperial Family, hoping to restore the monarchy, but ended up ostracized by the republican government. Admiral Saldanha da Gama led the Revolt of the Armada with the objective of restoring the Empire and allied himself with other monarchists who were fighting in the Federalist Revolution. However, all the attempts at restoration were violently crushed. High-ranking Monarchist officers were imprisoned, banished or executed by firing squad without due process of law and their subordinates also suffered harsh punishments.[31]

Early republic (1889–1917)

Example of vessels commissioned during this period:

.jpg) Protected cruiser Republica, 1892

Protected cruiser Republica, 1892 Transport Troops Comandante Freitas, 1896.

Transport Troops Comandante Freitas, 1896. Protected cruiser Almirante Barroso, 1896

Protected cruiser Almirante Barroso, 1896.jpg) Protected cruiser Tamandaré, 1897.

Protected cruiser Tamandaré, 1897..jpg) Coastal defence Deodoro, 1898.

Coastal defence Deodoro, 1898. Destroyer Gustavo Sampaio, 1898.

Destroyer Gustavo Sampaio, 1898. Torpedo cruiser Tupy, 1900.

Torpedo cruiser Tupy, 1900..jpg) Pará-class destroyer Rio Grande do Norte, 1908.

Pará-class destroyer Rio Grande do Norte, 1908. Battleship São Paulo, 1910.

Battleship São Paulo, 1910.- Cruiser Bahia, 1917.

Battleship Minas Geraes after its 1930s modernization, possibly during the Second World War.

Battleship Minas Geraes after its 1930s modernization, possibly during the Second World War.

Naval revolts

The military coup that led to the proclamation of the Brazilian Republic (1889), accentuated the decline of shipbuilding in the country. For four decades, between 1890 and 1930 no new ships were built in Brazil. The focus of republican governments was to equip the army to fight internal uprisings in the new regime's early years. The Navy was perceived as a threat to the new republican regime, as it had been more loyal to the Monarchy.

The situation became precarious in just over a decade as the Naval Battalion was reduced to 295 soldiers and Imperial Marines to 1,904 men. The equipment and vessels acquired were considered outdated by Navy officials, who criticized the abandonment of repair shops. Naval officers participated in two riots, known as Naval Riots. The second, avowedly monarchist, cost the officers their careers and their lives, without entering the military justice process. The sailors who obeyed orders and took part in the attempt to restore monarchy suffered cruelly.[32]

South American naval rivalry

Brazil's navy fell into disrepair and obsolescence in the aftermath of the 1889 revolution, which deposed Emperor Pedro II, after naval officers led a revolt in 1893–94.[33] Meanwhile, although the Argentine–Chilean agreement had limited their naval expansion, they still retained the numerous vessels built in the interim,[34] so around the start of the 20th century the Brazilian Navy lagged far behind its Argentine and Chilean counterparts in quality and total tonnage,[35] despite Brazil having nearly three times the population of Argentina and almost five times that of Chile.[36] The navy had just forty-five percent of its authorized personnel in 1896, and the only modern armored ships were two small coast-defense vessels launched in 1898.[37] Rising demand for coffee and rubber brought Brazil an influx of revenue in the early 1900s.[38] Simultaneously, there was a drive on the part of prominent Brazilians, most notably Pinheiro Machado and the Baron of Rio Branco,[upper-alpha 1] to have the country recognized as an international power. A strong navy was seen as crucial to this goal.[40] The National Congress of Brazil drew up and passed a large naval acquisition program in late 1904, but it was two years before any ships were ordered.[41]

Law no. 1452 was passed on 30 December 1905, which authorized £4,214,550 for new warship construction, £1,685,820 in 1906, three small battleships, three armored cruisers, six destroyers, twelve torpedo boats, three submarines, and two river monitors were ordered.[42] Though the Brazilian government later eliminated the armored cruisers for reasons of cost, the Minister of the Navy, Admiral Júlio César de Noronha, signed a contract with Armstrong Whitworth for three small battleships on 23 July 1906.[43]

British shipyards were ordered to build two dreadnought battleships, Minas Gerais and São Paulo; this started a naval arms race with Argentina and Chile. Later the Rio de Janeiro was order and sold and another the Riachuelo was never completed as a result of the First World War.

Revolt of the Lash

Soon after São Paulo's arrival, a major rebellion known as the Revolt of the Lash, or Revolta da Chibata, broke out on four of the newest ships in the Brazilian Navy. The initial spark was provided on 21 November 1910 when Afro-Brazilian sailor Marcelino Rodrigues Menezes was brutally flogged 250 times for insubordination. Many Afro-Brazilian sailors were sons of former slaves, or were former slaves freed under the Lei Áurea (abolition) but forced to enter the navy. They had been planning a revolt for some time, and Menezes became the catalyst. Further preparations were needed, so the rebellion was delayed until 22 November. The crewmen of Minas Geraes, São Paulo, the twelve-year-old Deodoro, and the new Bahia quickly took their vessels with only a minimum of bloodshed: two officers on Minas Geraes and one each on São Paulo and Bahia were killed.[44]

The ships were well-supplied with foodstuffs, ammunition, and coal, and the only demand of mutineers—led by João Cândido Felisberto—was the abolition of "slavery as practiced by the Brazilian Navy". They objected to low pay, long hours, inadequate training for incompetent sailors, and punishments including bôlo (being struck on the hand with a ferrule) and the use of whips or lashes (chibata), which eventually became a symbol of the revolt. By the 23rd, the National Congress had begun discussing the possibility of a general amnesty for the sailors. Senator Ruy Barbosa, long an opponent of slavery, lent a large amount of support, and the measure unanimously passed the Federal Senate on 24 November. The measure was then sent to the Chamber of Deputies.[45]

Humiliated by the revolt, naval officers and the president of Brazil were staunchly opposed to amnesty, so they quickly began planning to assault the rebel ships. The former believed such an action was necessary to restore the service's honor. Late on the 24th, the President ordered the naval officers to attack the mutineers. Officers crewed some smaller warships and the cruiser Rio Grande do Sul, Bahia's sister ship with ten 4.7-inch guns. They planned to attack on the morning of the 25th, when the government expected the mutineers would return to Guanabara Bay. When they did not return and the amnesty measure neared passage in the Chamber of Deputies, the order was rescinded. After the bill passed 125–23 and the president signed it into law, the mutineers stood down on the 26th.[46]

During the revolt, the ships were noted by many observers to be well-handled, despite a previous belief that the Brazilian Navy was incapable of effectively operating the ships even before being split by a rebellion.

World Wars (1917–1945)

Example of vessels commissioned during this period:

The Brazilian submarine Humaytá. Humaytá was a modified Balilla-class submarine built in Italy for the Brazilian Navy.

The Brazilian submarine Humaytá. Humaytá was a modified Balilla-class submarine built in Italy for the Brazilian Navy..jpg) Minelayer Camocim, 1940.

Minelayer Camocim, 1940..jpg) Monitor Paraguassú, 1940.

Monitor Paraguassú, 1940.- Cannon-class destroyer escort Beberibe, 1943.

.jpg) Corvette-minelayer Cabedelo, 1944.

Corvette-minelayer Cabedelo, 1944.

First World War (1917–1918)

After the declaration of war on the Central Powers in October 1917 the Brazilian Navy participated in the war. On 21 December 1917 the British government requested that a Brazilian naval force of light cruisers be placed under Royal Navy control and a squadron comprising the cruisers Rio Grande do Sul and Bahia, the destroyers Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte, Piauí, and Santa Catarina, and the support ship Belmonte and the ocean-going tug Laurindo Pitta was formed, designated the Divisão Naval em Operações de Guerra ("Naval Division in War Operations"). The DNOG sailed on 31 July 1918 from Fernando de Noronha for Sierra Leone, arriving at Freetown on 9 August, and sailing onwards to its new base of operations, Dakar, on 23 August. On the night of the 25 August the division believed it had been attacked by a U-boat when the auxiliary cruiser Belmonte sighted a torpedo track. The purported submarine was depth-charged, fired on, and reportedly sunk by the Rio Grande do Norte, but the sinking was never confirmed.

The DNOG patrolled the Dakar-Cape Verde-Gibraltar triangle, which was suspected to be used by U-boats waiting on convoys, until 3 November 1918 when it sailed for Gibraltar to begin operations in the Mediterranean, with the exception of the Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Norte, and Belmonte. The Division arrived at Gibraltar on 10 November; while passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, they mistook three USN subchasers for U-boats but no damage was caused.[47]

Second World War (1942–1945)

Having the Suez Canal blocked and the necessity to go beyond to the far East, Germany used the Atlantic Ocean to maintain its supply of material necessities.

In World War II, Brazil's navy was obsolete. In early 1942, German submarines aimed to interdict supplies from reaching Britain and the Soviet Union. Between 1942 and 1944, Brazil's Navy was supported by the United States Navy. During this period several naval bases were established in the North and Northeast of Brazil, becoming the headquarters of the Allied Command Atlantic South.

Within their limitations and with the refitting and reorganization promoted with American resources, the Brazilian Navy participated actively in the fight against U-boats in the South, Central Atlantic and also the Caribbean. They guarded allied convoys bound for North Africa and the Mediterranean. Between 1942 and 1945 the navy was responsible for conducting 574 convoy operations protecting 3164 merchant ships of various nationalities. Enemy submarines managed to sink only three vessels. According to German documentation the Brazilian Navy made over sixty-six attacks against German submarines.

A total of nine U-boats known German submarines were destroyed along the Brazilian coast. Those were: U-164, U-128, U-590, U-513, U-662, U-598, U-199, U-591, and U-161

About 1,100 Brazilians died during the Battle of the Atlantic as a result of the sinking of 32 Brazilian merchant vessels and a naval warship. Among the 972 dead from the merchant vessels, 470 were crew and 502 were civilian passengers.[48] Besides these, 99 sailors died in the sinking of the Vital de Oliveira when she was attacked by German submarines, in addition to some 350 deaths in accidents that resulted in the sinking of the corvette Camaquã on July 21, 1944. The cruiser Bahia was sunk by an explosion on July 4, 1945 which resulted in the deaths of over 300 men.

Cold war period (1945–2000)

Example of vessels commissioned during this period:

_2.jpg) Destroyer Araguari, 1949.

Destroyer Araguari, 1949..jpg)

.jpg) Fletcher-class destroyer Piaui, 1963.

Fletcher-class destroyer Piaui, 1963. Aircraft carrier Minas Gerais, 1970.

Aircraft carrier Minas Gerais, 1970..jpg) Submarine Riachuelo, 1975.

Submarine Riachuelo, 1975..jpg) Corvette Caboclo, 1980.

Corvette Caboclo, 1980. Destroyer Parana, 2000.

Destroyer Parana, 2000..jpg) Transport troops Ary Parreira, 2002.

Transport troops Ary Parreira, 2002.

Lobster War (1961–1963)

_underway_with_destroyers_during_the_1961_Lobster_War.jpg)

In 1961, some groups of French fishermen who were operating very profitably off the coast of Mauritania extended their search to the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, settling on a spot off the coast of Brazil where lobsters are found on submerged ledges at depths of 250–650 ft. But local fishermen complained that large boats were coming from France to catch lobster off the state of Pernambuco, so the Brazilian Admiral Arnoldo Toscano ordered two corvettes to sail to the area where the French fishing boats were located. Seeing that the fishermen's claim was justifiable, the captain of the Brazilian vessel then demanded that the French boats receded to deeper water, leaving the continental shelf to smaller Brazilian vessels. The situation became very tense once the French rejected this demand and radioed a message asking for the French government to send a destroyer to accompany the lobster boats, which prompted the Brazilian government to put its many ships on state of alert.

French Government dispatched on 21 February the T 53-class destroyer to watch over the fishing boats, but it was promptly repelled by a Brazilian warship and the aircraft carrier Minas Gerais.

1964 Coup d'état

Although corporal punishment was officially abolished after the Revolt of the Lash, or Revolta da Chibata, at the end of 1910, improvement in working conditions and career plans were still contentious in early 1960. The dissatisfaction with officialdom and conservative politicians, coupled with the lack of vision and inability of the general policy of then president João Goulart, led the sailors, encouraged by leaders such as Corporal Anselmo, to the military coup of 1964.

The purges carried out later (not just the Navy but for all the armed forces), and the establishment of certain criteria for selection of its new members were a military term in the Brazilian tradition among its members openly harboring various currents of political thought.

The Colossus-class aircraft carrier Minas Gerais served the Navy until its decommissioning in 2001.

The carrier was commissioned into the Marinha do Brasil as NAeL Minas Gerais (named for Kubitschek's home state) on 6 December 1960. She departed Rotterdam for Rio de Janeiro on 13 January 1961. The duration of the refit meant that while the carrier was the first purchased by a Latin American nation, she was the second to enter service, after another Colossus-class carrier entered service with the Argentine Navy as ARA Independencia in July 1959.

Peacekeeping Operations (2004–present)

Haiti

On May 28, 2004 four Brazilian Navy ships (Mattoso Maia, Rio de Janeiro, Almirante Gastão Motta, Bosísio) departed from Rio de Janeiro bound for Haiti on a peace mission coordinated by the United Nations (UN). The ships transported part of the military contingent that was involved in Haitian reconstruction. In addition to 150 Marines and Army troops, the ships carried most of the materiel for the Brazilian stabilization force – approximately 120 vehicles, 26 trailers of various types, and 81 containers loaded with equipment and supplies.[49] On February 28, 2010, the Brazilian Navy ship Garcia D'Avila sailed from Rio de Janeiro with 900 tons of cargo, including humanitarian aid supplies to earthquake victims in Haiti as well as equipment for the Brazilian military that operates in that country.

Ammunition was brought for Brazilian soldiers in addition to 14 power generators and 30 vehicles, including trucks, ambulances and armored vehicles. The ship's crew consisted of 350 mariners.[50]

Lebanon

.jpg)

On 15 February 2011, Brazil assumed command of the Maritime Task Force (MTF) of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL).[51] On 4 October the Brazilian Ministries of Defence and Foreign Relations informed authorities that Brazil was sending a Navy vessel with up to 300 crew members, equipped with an aircraft, to join the fleet in Lebanon and the vessel was authorized by the National Congress.[52] On 25 November 2011 the frigate União with 239 officers and sailors aboard joined the task force, bringing to nine the number of vessels assisting the Lebanese Navy in monitoring Lebanese territorial waters.

The frigate served as the flagship for Rear Admiral Luiz Henrique Caroli of Brazil who had been Commander of UNIFIL-MTF since February.[53]

On 10 April 2012 the frigate Liberal (F43) left Rio de Janeiro bound for Lebanon to join the force.[54] It was relieved in January 2013 by the frigate Constituição (F42) which joined a multinational group comprising nine ships; three from Germany, two from Bangladesh, one from Greece, one from Indonesia and one from Turkey. The crew comprised 250 military officials. The return to Rio was scheduled for August 2013.[55]

On 8 August 2015 the corvette Barroso left Rio de Janeiro to replace União and later that month carried out maritime interdiction operations and provided training to the Lebanese Navy.[56] On 4 September 2015 it rescued 220 Syrian migrants in the Mediterranean Sea, as reported by the Ministry of Defense in a statement released on its website. The Brazilian ship was sailing towards Beirut in Lebanon when it received an alert from the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) about a sinking vessel taking immigrants to Europe.[56]

Notable naval battles involving the Brazilian Navy

Brazilian War of Independence

- Battle of 4 May – The largest naval battle of the War of Independence. The Brazilian and Portuguese fleets clashed with inconclusive results.

- Siege of Salvador – Brazilian Imperial warships surrounding troops and Portuguese ships in Salvador, Bahia.

- Battle of Montevideo – Imperial naval forces sought to capture the last Portuguese redoubt in the Cisplatina province.

Cisplatine War

- Battle of Monte Santiago – The Imperial Navy, commanded by James Norton, surprised and chased an Argentine squad.

Platine War

- Battle of The Tonelero Pass – An Imperial naval force forced passage under an artillery barrage from the Argentine Army.

Uruguayan War

- Siege of Salto – Imperial Navy blockade and bombing of the city of Salto, Uruguay.

- Siege of Paysandú – Imperial warships siege and bombard the city of Paysandú.

Paraguayan War

- Battle of Riachuelo – Largest naval battle of the Brazilian Navy history, one of the most important in South America. Involved Brazilian and Paraguayan naval forces.

- Battle of Paso de Cuevas – Brazilian and Argentine warships successfully pass Argentine troops at the Cuevas Pass on the Rio Paraná.

- Battle of Curuzú – Brazilian Imperial warships bombardment of Curuzú fortifications.

- Siege of Humaitá – Passage of the Imperial fleet before the fortification of Humaitá on the Rio Paraguay.

World War I

- U-boat Campaign (World War I) – Brazilian squad created to patrol the area between Dakar-Cape Verde-Gibraltar, during World War I.

World War II

- Battle of the Atlantic – Brazilian warships against German submarines in World War II.

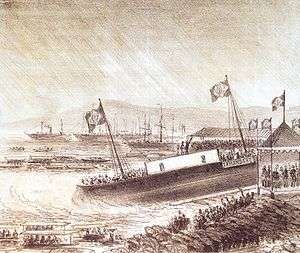

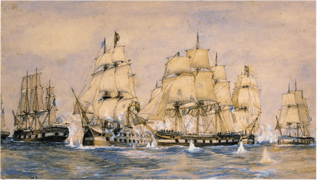

Brazilian Imperial Navy in the Battle of 4 May.

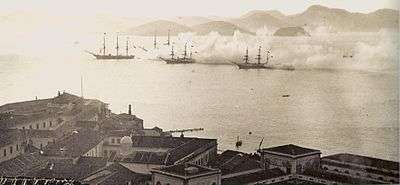

Brazilian Imperial Navy in the Battle of 4 May. The Brazilian fleet blockading Buenos Aires celebrates the end of the Cisplatine War in 1828.

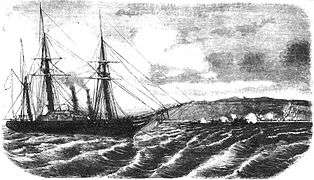

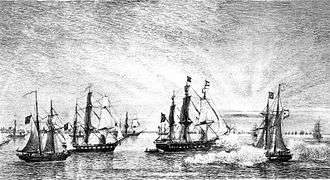

The Brazilian fleet blockading Buenos Aires celebrates the end of the Cisplatine War in 1828. Passage of the Tonelero during the Platine War (1851–52).

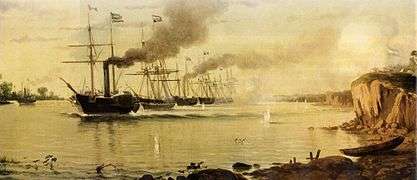

Passage of the Tonelero during the Platine War (1851–52). The Naval Battle of Riachuelo was a key victory during the Paraguayan War, 1865.

The Naval Battle of Riachuelo was a key victory during the Paraguayan War, 1865. Battle of Curuzú Naval Warfare in Paraguay: Brazilian Ironclad Rio de Janeiro, launched 1866 and sunk by a mine the same year on the Paraná River.

Battle of Curuzú Naval Warfare in Paraguay: Brazilian Ironclad Rio de Janeiro, launched 1866 and sunk by a mine the same year on the Paraná River. Paraguayan Canoes giving approach to Brazilian monitor Alagoas, riverine warfare in 1866.

Paraguayan Canoes giving approach to Brazilian monitor Alagoas, riverine warfare in 1866. Imperial fleet bombing the fortification Humaitá.

Imperial fleet bombing the fortification Humaitá. Brazilian navy in anti-submarine warfare, Atlantic ocean, 1942.

Brazilian navy in anti-submarine warfare, Atlantic ocean, 1942.

Brazilian Navy today

Personnel

As of 2011, the Brazilian Navy has a reported strength of 60,000 active personnel,[57] of which approximately 15,000 are naval infantry. The current Navy Commander is Admiral Eduardo Leal Ferreira.[58]

Ships and submarines

As of 2012, the Brazilian Navy had about 100 commissioned ships,[59] with others undergoing construction, acquisition and modernization. Between 1996 and 2005 the Navy retired 21 ships.[60] The Brazilian Navy operated one Clemenceau-class aircraft carrier, the São Paulo, formerly the French Navy's Foch. It was retired in 2017.[61] Its possible replacements are presently in the early stage of planning and will not be expected until at least 2025.[62]

Four Tupi-class and one Tikuna-class Type 209 submarines are in the fleet. The Tupi-class submarines will be upgraded by Lockheed Martin at a cost of $35 million.[63] The modernization includes the replacement of existing torpedoes with new MK 48 units.[64] On March 14, 2008, the Navy purchased four Scorpène-class submarines from France.[65] The Navy is currently developing its first nuclear submarine.[66] The Navy plans to have the Scorpène-class submarines in service in 2017, and their first nuclear-powered submarine commissioned in 2023.[67]

In August 2008 the Navy incorporated the corvette Barroso, which was designed and built in Brazil[68] at a cost of $263 million.[69] In August 2012 the Navy requested 4 new ships based on the Barroso class but redesigned using a stealth design.

The PROSUPER program plans to acquire, firstly, five new 6,000 tons frigates, five new OPV and one Logistics Support Vessel.

In January 2012 BAE Systems contracted to supply three patrol vessels that were Port of Spain-class corvettes. The contract is worth £133m. The ocean patrol vessels are already built, originally ordered by the government of Trinidad and Tobago in a contract which was terminated in 2010.[70][71] The first vessel was commissioned at the end of June 2012, the second was scheduled for December 2012 and the last in April 2013.[72]

In March 2014, the Brazilian Navy announced plans to domestically build an aircraft carrier, with plans to enter service around 2029. Originally, the São Paulo was to be modernized until its introduction, but escalating repair costs forced its retirement in February 2017. The carrier will likely be based on an existing project and be built with a foreign partner. French company DCNS has a strong presence in Brazil and is already engaged in building five submarines and a naval base in the country. The company has been showcasing their DEAC Aircraft Carrier project based on the Charles de Gaulle carrier's design and aviation systems including launching conventional take-off aircraft, unmanned aerial vehicle integration, advanced conventional propulsion, and platform stabilization systems. American company General Atomics is marketing their Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) to Brazil. Possible aircraft to be operated by the carrier may include the Saab Sea Gripen, given that the Air Force has chosen the land-based version as their new jet fighter.[73]

Aircraft

As of 2011, the Naval Aviation arm of the Navy operates around 85 aircraft. All the aircraft, with the exception of the A-4 Skyhawks, are helicopters.

A Brazilian Westland Super Lynx Mk-21A.

A Brazilian Westland Super Lynx Mk-21A. A Brazilian Aérospatiale AS-332 Super Puma

A Brazilian Aérospatiale AS-332 Super Puma A Brazilian SH-3 Sea King

A Brazilian SH-3 Sea King.jpg) A Brazilian Bell 206 Jet Ranger

A Brazilian Bell 206 Jet Ranger.jpg) A Brazilian HB350 Esquilo

A Brazilian HB350 Esquilo A Brazilian McDonnell Douglas AF-1 Skyhawk

A Brazilian McDonnell Douglas AF-1 Skyhawk A Brazilian S-70B Seahawk

A Brazilian S-70B Seahawk A Brazilian EC-725 Cougar

A Brazilian EC-725 Cougar_during_UNITAS_exercises.jpg) A Brazilian Eurocopter AS355

A Brazilian Eurocopter AS355

Marines

The Brazilian Marine Corps (Portuguese: Corpo de Fuzileiros Navais; CFN)[74] is the land combat branch of the Brazilian Navy.

.jpg) Brazilian marines protection in response to chemical emergencies

Brazilian marines protection in response to chemical emergencies.jpg) Marines corps in riverine operations.

Marines corps in riverine operations..jpg) Brazilian AAV amphibious vehicle in action

Brazilian AAV amphibious vehicle in action.jpg) Landing ship dock amphibious vehicles.

Landing ship dock amphibious vehicles..jpg) Rocket artillery in Brazilian Marines Corps

Rocket artillery in Brazilian Marines Corps.jpg) Marines on patrol boat for river

Marines on patrol boat for river.jpg) convoy of AAV vehicles

convoy of AAV vehicles.jpg) Mowag Piranha III 8x8

Mowag Piranha III 8x8.jpg) Anti-Aircraft cannon

Anti-Aircraft cannon.jpg) Mistral missile system

Mistral missile system

Structure and organisation

Branches

The main branches of the Brazilian Navy are:[75]

- The "Comando de Operações Navais" (Naval Operations Command)

- The "Comando da Força de Superfície" (Surface Fleet Command)

- The "Comando da Força de Submarinos" (Submarine Fleet Command)

- The "Comando da Força Aeronaval" (Naval Aviation Command)

- The "Comando da 1ª Divisão da Esquadra" (1st Fleet Division Command)

- The "Comando da 2ª Divisão da Esquadra" (2nd Fleet Division Command)

- The "Comando Geral do Corpo de Fuzileiros Navais" (Marine Corps General Command)

Naval Districts

_fires_at_an_unmanned_aerial_vehicle_during_a_drone_exercise_(DRONEX)_with_ship.jpg)

- 1º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Rio de Janeiro-RJ)

- 2º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Salvador-BA)

- 3º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Natal-RN)

- 4º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Belém-PA)

- 5º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Rio Grande-RS)

- 6º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Ladário-MS)

- 7º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Brasilia-DF)

- 8º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (São Paulo-SP)

- 9º Distrito Naval da Marinha do Brasil (Manaus-AM)

Naval bases

_team.jpg)

As of 2009, the main naval bases in use are:[76]

- Rio de Janeiro:

- "Base Naval Almirante Castro e Silva", submarine base

- "Base Naval do Rio de Janeiro", main naval base

- "Arsenal da Marinha do Rio de Janeiro", naval shipyard

- "Base Aérea Naval de São Pedro da Aldeia", naval aviation base

- "Base de Fuzileiros Navais da Ilha do Governador", marine corps base

- "Base de Fuzileiros Navais da Ilha das Flores", marine corps base

- "Base de Fuzileiros Navais do Rio Meriti", marine corps base

- Bahia:

- "Base Naval de Aratu", naval base and repair facility

- Rio Grande do Norte:

- "Base Naval de Natal", naval base

- "Base Naval Almirante Ary Parreiras", naval base and repair facility

- Pará:

- "Base Naval de Val-de-Cães", naval base and repair facility

- Mato Grosso do Sul:

- Amazonas:

- "Estação Naval do Rio Negro", riverine naval base and repair facility

- Rio Grande do Sul:

- "Estação Naval do Rio Grande", naval base

Gallery

.jpg) Brazilian Navy ship Greenhalgh (F46) steams through the Atlantic during the Iwo Jima Expeditionary Strike Group composite unit training exercise

Brazilian Navy ship Greenhalgh (F46) steams through the Atlantic during the Iwo Jima Expeditionary Strike Group composite unit training exercise Brazilian submarine formation

Brazilian submarine formation Brazilian Navy corvette Júlio de Noronha

Brazilian Navy corvette Júlio de Noronha Tupi-class submarine Tamoio

Tupi-class submarine Tamoio River Patrol Boat Rondônia

River Patrol Boat Rondônia.jpg) Parnaíba (U17) River Monitor

Parnaíba (U17) River Monitor River Patrol boat Pampeiro (P12) camouflaged Amazon region

River Patrol boat Pampeiro (P12) camouflaged Amazon region.jpg) The Brazilian frigate BNS Constituição (F42)

The Brazilian frigate BNS Constituição (F42) Destroyer Paraíba (D28)

Destroyer Paraíba (D28).jpg) Imperial Marinheiro-class corvette Solimões (V24).

Imperial Marinheiro-class corvette Solimões (V24)..jpg) Destroyer Pará (D27).

Destroyer Pará (D27). Brazilian navy in Amazonian River Basin.

Brazilian navy in Amazonian River Basin._on_the_Minas_Gerais_Schleiffert-1.jpg) Brazilian aircraft carrier Minas Gerais.

Brazilian aircraft carrier Minas Gerais..jpg)

See also

- Armed Forces of the Empire of Brazil

- Imperial Brazilian Navy

- Naval Revolt

- Brazilian Marine Corps

- Brazilian Naval Aviation

- Brazilian Army

- Brazilian Air Force

- Military history of Brazil

- Military ranks of Brazil

- Brazil and weapons of mass destruction

Notes

- ↑ A professional diplomat and the son of the famed Viscount of Rio Braco, the Baron of Rio Branco was named as Brazil's Foreign Minister in 1902 after a distinguished career as a diplomat, and served there until his death in 1912. In that time, he oversaw the signing of many treaties and mediated territorial disputes between Brazil and its neighbors, and became a famous name in his own right.[39]

References

- ↑ Comandante da Marinha confirma nova esquadra no Nordeste [Navy commander confirms new Northeastern fleet] (in Portuguese), Marinha do Brasil, 2009-01-26, archived from the original on 2011-05-24, retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ↑ "Oceanographic and Meteorological Data Buoys", Hydro International, retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ↑ Holanda 1974, p. 260.

- ↑ Maia 1975, p. 53.

- ↑ Maia 1975, pp. 58–61.

- 1 2 Holanda 1974, p. 261.

- ↑ Maia 1975, pp. 54–57.

- 1 2 Holanda 1974, p. 272.

- ↑ Maia 1975, pp. 133–35.

- ↑ Holanda, p. 264.

- ↑ Maia 1975, p. 216.

- 1 2 Holanda 1974, p. 264.

- ↑ Maia 1975, pp. 205–6.

- ↑ Maia 1975, p. 210.

- ↑ Janotti 1986, pp. 207–8.

- ↑ Holanda 1974, p. 265.

- ↑ Carvalho 1975, p. 181.

- ↑ Holanda 1974, p. 266.

- ↑ Salles 2003, p. 38.

- ↑ Maia 1975, p. 219.

- 1 2 3 Janotti 1986, p. 208.

- ↑ Schwarcz 2002, p. 305.

- ↑ Doratioto 1996, p. 23.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, p. 466.

- 1 2 Maia 1975, p. 225.

- ↑ Maia 1975, p. 221.

- ↑ Maia 1975, pp. 221, 227.

- ↑ Calmon 2002, p. 265.

- ↑ Calmon 1975, p. 1603.

- ↑ Janotti 1986, p. 66.

- ↑ Janotti 1986, p. 209.

- ↑ Janotti 1986. However, the question directly involved in the revolt was confined to the text of Brazilian Constitution of 1891 regarding the vacancy of the President.

- ↑ Grant, Rulers, Guns, and Money, 148; Martins, A marinha brasileira, 56, 67; Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 32; Topliss, "Brazilian Dreadnoughts", 240.

- ↑ Scheina, Naval History, 45–52; Garrett, "Beagle Channel", 86–88.

- ↑ Martins, A marinha brasileira, 50–51; Martins, "Colossos do mares", 75; Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 32.

- ↑ Scheina, "Brazil", 403; Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy", 32.

- ↑ Love, Revolt, 16; Sondhaus, Naval Warfare, 216; Scheina, "Brazil", 403.

- ↑ Scheina, "Brazil", 403.

- ↑ Love, Revolt, 8–9.

- ↑ Love, Revolt, 14; Scheina, Naval History, 80.

- ↑ Scheina, Naval History, 80; Scheina, "Brazil", 403; Topliss, "Brazilian Dreadnoughts", 240.

- ↑ English, Armed Forces, 108; Scheina, Naval History, 80; Grant, Rulers, Guns, and Money, 147; Martins, A marinha brasileira, 75, 78.

- ↑ Martins, A marinha brasileira, 80; Topliss, "Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 240–46.

- ↑ Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 32–38, 50.

- ↑ Morgan, The Revolt of the Lash, 40–42.

- ↑ Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 44–46.

- ↑ Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900–2001. Brassey's. pp. 38–39. ISBN 1-57488-452-2.

- ↑ Bento, Cláudio Moreira (1995), "Participação das Forças Armadas e da Marinha Mercante do Brasil na Segunda Guerra Mundial (1942–1945)" [Participation of the Armed Forces and Merchant Navy of Brazil in World War II (1942–1945)], Gazetilha (in Portuguese), Volta Redonda, RJ: AHIMTB.

- ↑ "Brazilian ships leave for Haiti on peace mission". Agência Brasil. EBC. 2004-05-27. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "Brazilian Navy ship leaves for Haiti with humanitarian aid and military equipment". Portal Brasil. Brazilian government. 2010-02-28. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "Participação brasileira na Unifil" [Brazilian Unifil participation] (in Portuguese). Ministério das Relações Exteriores. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "Brazilian Navy ship to travel to Lebanon". Agência de Notícias Brasil Árabe. BR: Acha notícias. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL)". UN missions. Archived from the original on 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "Marinha do Brasil envia navio para operação de paz no Líbano" [Brazilian Navy sends ship to peace operations in Lebanon] (in Portuguese). Tecnologia & Defesa. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ Diplomacia [Diplomacy] (news) (in Portuguese), Anba.

- 1 2 http://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/en/internacional/noticia/2015-09/brazilian-navys-corvette-rescues-migrants-mediterranean-sea

- ↑ Comandante da Marinha confirma nova esquadra no Nordeste [Navy Commander confirms new fleet in the Northeast] (in Portuguese), Brazilian Navy, archived from the original on 2011-05-24, retrieved 2009-02-01

- ↑ Comandantes da Marinha na República [Republican Navy Commanders] (in Portuguese), Brazilian Navy, archived from the original on December 15, 2009, retrieved June 10, 2009

- ↑ "Uma nova agenda militar" [A new military agenda], Época (in Portuguese), archived from the original on 2017-03-25, retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ BRAZILIAN NAVY RETIRES SAO PAOLO CARRIER

- ↑ Guisnel, Jean (6 December 2011), "France is in the running for two aircraft carriers for Brazilian Navy", World Naval Forces News, Navy recognition.

- ↑ "Brazil seeks to modernize submarine Force", Mercopress, 2008-02-05, retrieved 2014-01-19.

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin Awarded $35 Million Contract to Modernize Brazilian Navy Submarine Force", Money, CNN.com, retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ "Brazil To Start With Scorpène", Strategy Page, retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ↑ "Brazil to get nuclear sub technology from France", Americas, CNN, retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ↑ "Navy plans to get first nuclear sub", Dmilt, March 6, 2013.

- ↑ Incorporação da Corveta Barroso [Barroso corvette commissioning] (in Portuguese), Brazilian Navy, retrieved 2008-11-25

- ↑ "Navio Mais Barato" [Cheaper ship], Dinheiro (in Portuguese), Istoé, retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ↑ "BAE Systems sells patrol vessels to Brazil". BBC News. 2012-01-02.

- ↑ Defense news.

- ↑ Фрегат ‘Таркаш’ планируется передать ВМС Индии в ноябре этого года [Frigate ‘Tarkash’ planned to be delivered to the Indian Navy in November] (in Russian). RU: Flotprom. 2012-06-26. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ Brazil planning to build an Aircraft Carrier with a foreign partner - Navyrecognition.com, 12 March 2014

- ↑ Trevor Nevitt Dupuy (1993). International military and defense encyclopedia, Volume 1. Brassey's (US). p. 137.

- ↑ "Estrutura de Comando", A estrutura militar do Brasil [The Brazilian military structure] (in Portuguese), Defesa Brasil, retrieved 2009-06-10

- ↑ Wertheim, Eric (2007), The Naval Institute Guide to Combat Fleets of the World, Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-59114-955-2, retrieved 2009-10-06.

Sources

- Doratioto, Francisco (2002). Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai [Cursed War: New War history of Paraguay] (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- English, Adrian J. (1984), Jane's Armed Forces of Latin America, London and New York: Jane's, ISBN 0-7106-0321-5, OCLC 11537114

- Garrett, James L (Autumn 1985), "The Beagle Channel Dispute: Confrontation and Negotiation in the Southern Cone", Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs, Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Miami, 27 (3): 81–109, JSTOR 165601, doi:10.2307/165601.

- Grant, Jonathan A (Mar 2007), Rulers, Guns & Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism (hardback), Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02442-7.

- de Holanda, Sérgio Buarque (1974). Declínio e queda do Império [Decline and Fall of the Empire]. História Geral da Civilização Brasileira (in Portuguese) (2 ed.). São Paulo: Difusão européia do livro.

- Janotti, Maria de Lourdes Monaco (1986). Os Subversivos da República [The Republic’s subversives] (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Brasiliense.

- Livermore, Seward W (Mar 1944), "Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925", The Journal of Modern History, The University of Chicago Press, 16 (1): 31–48, JSTOR 1870986, doi:10.1086/236787.

- Love, Joseph L (2012), The Revolt of the Whip, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-8109-5, OCLC 757838402.

- Maia, Prado (1975). A Marinha do Brasil na colônia e no Império [The Navy of Brazil in the Colony and the Empire] (in Portuguese) (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Cátedra.

- Martins, João Roberto filho (2007), "Colossos do mares" [Sea colossuses], Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional, 3 (27): 74–77, ISSN 1808-4001, OCLC 61697383.

- ——— (2010), A marinha brasileira na era dos encouraçados, 1885–1910: tecnologia, Forças Armadas e política [The Brazilian Navy in the ironclads era, 1885–1910: technology, armed forces & politics] (in Portuguese), Rio de Janeiro: FGV, ISBN 978-85-225-0803-7, OCLC 679733899.

- Morgan, Zachary R (2003), "The Revolt of the Lash, 1910", in Bell, Christopher M; Elleman, Bruce A, Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective, Portland, OR: Frank Cass, pp. 32–53, ISBN 0-7146-8468-6, OCLC 464313205.

- Scheina, Robert L (1984), "Brazil", in Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, pp. 403–7, ISBN 0-87021-907-3, OCLC 12119866.

- ——— (1987), Latin America: A Naval History, 1810–1987 (ill ed.), Annapolis, MD: Naval Inst Press, ISBN 978-0-87021-295-6, OCLC 15696006.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz (2002), As Barbas do Imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos [The Emperor’s beard: D. Peter II, a king in the tropics] (in Portuguese) (2 ed.), São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Topliss, David (1988), "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 1904–1914", Warship International, 25 (3): 240–89, ISSN 0043-0374, OCLC 1647131.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brazilian Navy. |

- Brazilian Navy Official website (in Portuguese)

- Poder Naval Brazilian warships and naval aviation (in Portuguese)

- Official histories of Brazilian ships (in Portuguese)

- Global Security Brazilian Navy profile

- History of World's Navy's Ships of the Brazilian Navy

- History of VF-1 "Falcões" (Hawks) in the Brazilian Navy

- Brazilian naval flags

- Base Militar Web Magazine's Brazilian military aircraft data base

- Military Orders and Medals from Brazil (in Portuguese)