Marija Gimbutas

| Marija Gimbutas | |

|---|---|

Prof. Dr. Marija Gimbutas at the Frauenmuseum Wiesbaden, Germany 1993 | |

| Born |

Marija Birutė Alseikaitė January 23, 1921 Vilnius, Lithuania |

| Died |

February 2, 1994 (aged 73) Los Angeles |

| Nationality | Lithuanian-American |

| Other names | Lithuanian: Marija Gimbutienė |

| Alma mater | Vilnius University |

| Occupation | archaeologist |

| Years active | 1949–1991 |

| Known for | Kurgan hypothesis |

| Notable work | The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe (1974); The Language of the Goddess (1989); The Civilization of the Goddess (1991) |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

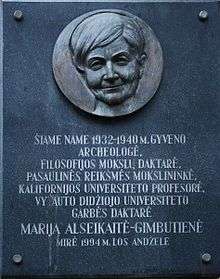

Marija Gimbutas (Lithuanian: Marija Gimbutienė; January 23, 1921 – February 2, 1994), was a Lithuanian-American archaeologist known for her research into the Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures of "Old Europe" and for her Kurgan hypothesis, which located the Proto-Indo-European homeland in the Pontic Steppe.

Biography

Early life

Born as Marija Birutė Alseikaitė to Veronika Janulaitytė-Alseikienė and Danielius Alseika in Vilnius, the capital of Republic of Central Lithuania, she had members of the Lithuanian intelligentsia as parents.[1] Her mother received a doctorate in ophthalmology at the University of Berlin in 1908 and became the first female physician in Lithuania, while her father received his medical degree from the University of Tartu in 1910. After the 1917 Russian Revolution, Gimbutas' parents founded the first Lithuanian hospital in the capital.[1] During this period, her father also served as the publisher of the newspaper Vilniaus Žodis and the cultural magazine Vilniaus Šviesa and was an outspoken proponent of Lithuanian independence during the Poland-Lithuanian War.[2] Gimbutas' parents were connoisseurs of traditional Lithuanian folk arts and frequently invited contemporary musicians, writers, and authors to their home, including Vydūnas, Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas, and Jonas Basanavičius.[3] With regard to her strong cultural upbringing, Gimbutas said:

I had the opportunity to get acquainted with writers and artists such as Vydunas, Tumas-Vaižgantas, even Basanavičius, who was taken care of by my parents. When I was four or five years old, I would sit in Basanavičius's easy chair and I would feel fine. And later, throughout my entire life, Basanavičius's collected folklore remained extraordinarily important for me.[3]

In 1931, Gimbutas settled with her parents in Kaunas, the temporary capital of Lithuania, where she continued her studies. After her parents separated that year, she lived with her mother and brother, Vytautas, in Kaunas. Five years later, her father died suddenly. At her father's deathbed, Gimbutas pledged that she would study to become a scholar: "All of a sudden I had to think what I shall be, what I shall do with my life. I had been so reckless in sports—swimming for miles, skating, bicycle riding. I changed completely and began to read."[4][5]

In 1941, she married architect Jurgis Gimbutas.

During the Second World War, Gimbutas lived under both Soviet and German occupations from 1940 to 1941 and 1941 to 1943, respectively.[6]

Emigration

A year after the birth of their first daughter, Danutė, in June 1942, the young Gimbutas family fled the country in the wake of the Soviet re-occupation, first to Vienna and then to Innsbruck and Bavaria.[7] In her reflection of this turbulent period, Gimbutas remarked, "Life just twisted me like a little plant, but my work was continuous in one direction."[8]

While holding a postdoctoral fellowship at Tübingen the following year, Gimbutas gave birth to her second daughter, Živilė. She did postgraduate work at the University of Heidelberg and the University of Munich in 1947 to 1949. The Gimbutas family left Germany and relocated to the United States in 1949.[7][9][10]

Her third daughter, Rasa Julija, was born August 1954 in Boston

Death

She died in Los Angeles in 1994, at age 73. Soon afterwards, she was interred in Kaunas's Petrašiūnai Cemetery.

Career

From 1936, she participated in ethnographic expeditions to record traditional folklore and studied Lithuanian beliefs and rituals of death.[1] She graduated with honors from Aušra Gymnasium in Kaunas in 1938 and enrolled in the Vytautas Magnus University the same year, where she studied linguistics in the Department of Philology. She then attended the University of Vilnius to pursue graduate studies in archaeology (under Jonas Puzinas), linguistics, ethnology, folklore and literature.[1]

In 1942 she completed her master's thesis, "Modes of Burial in Lithuania in the Iron Age", with honors.[1] She received her Master of Arts degree from the University of Vilnius, Lithuania, in 1942.

In 1946, Gimbutas received a doctorate in archaeology, with minors in ethnology and history of religion, from Tübingen University with her dissertation "Prehistoric Burial Rites in Lithuania" (in German), which was published later that year.[7]

After arriving in the United States, Gimbutas immediately went to work at Harvard University translating Eastern European archaeological texts. She then became a lecturer in the Department of Anthropology. In 1955 she was made a Fellow of Harvard's Peabody Museum.

Kurgan hypothesis

In 1956 Gimbutas introduced her Kurgan hypothesis, which combined archaeological study of the distinctive Kurgan burial mounds with linguistics to unravel some problems in the study of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) speaking peoples, whom she dubbed the "Kurgans"; namely, to account for their origin and to trace their migrations into Europe. This hypothesis, and the act of bridging the disciplines, has had a significant impact on Indo-European studies.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Gimbutas earned a reputation as a world-class specialist on Bronze Age Europe, as well as on Lithuanian folk art and the prehistory of the Balts and Slavs, partly summed up in her definitive opus, Bronze Age Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe (1965). In her work she reinterpreted European prehistory in light of her backgrounds in linguistics, ethnology, and the history of religions, and challenged many traditional assumptions about the beginnings of European civilization.

As a Professor of European Archaeology and Indo-European Studies at UCLA from 1963 to 1989, Gimbutas directed major excavations of Neolithic sites in southeastern Europe between 1967 and 1980, including Anzabegovo, near Štip, Republic of Macedonia, and Sitagroi and Achilleion in Thessaly (Greece). Digging through layers of earth representing a period of time before contemporary estimates for Neolithic habitation in Europe – where other archaeologists would not have expected further finds – she unearthed a great number of artifacts of daily life and of religious cults, which she researched and documented throughout her career. During her successful career, Gimbutas stated, "After a millennium when the Hun Empire collapsed, a distinct Slavic culture re-emerged and spread rapidly," and "Neither Bulgars nor Avars colonized the Balkan Peninsula, after storming Thrace, Illyria and Greece they went back to their territory north of the Danube. It was the Slavs who did the colonizing."

Three genetic studies in 2015 gave support to the Kurgan theory of Gimbutas regarding the Indo-European Urheimat. According to those studies, haplogroups R1b and R1a, now the most common in Europe (R1a is also common in South Asia) would have expanded from the Russian steppes, along with the Indo European languages; they also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as Indo European Languages.[11][12][13]

Late archaeology

Gimbutas gained fame and notoriety in the English-speaking world with her last three English-language books: The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe (1974); The Language of the Goddess (1989), which inspired an exhibition in Wiesbaden, 1993-4; and the last of the three, The Civilization of the Goddess (1991), which, based on her documented archaeological findings, presented an overview of her conclusions about Neolithic cultures across Europe: housing patterns, social structure, art, religion, and the nature of literacy.

The Civilization of the Goddess articulated what Gimbutas saw as the differences between the Old European system, which she considered goddess- and woman-centered (gynocentric), and the Bronze Age Indo-European patriarchal ("androcratic") culture which supplanted it. According to her interpretations, gynocentric (or matristic) societies were peaceful, honored women, and espoused economic equality.

The androcratic, or male-dominated, Kurgan peoples, on the other hand, invaded Europe and imposed upon its natives the hierarchical rule of male warriors.

Gimbutas' work, along with that of her colleague, mythologist Joseph Campbell, is housed in the OPUS Archives and Research Center on the campus of the Pacifica Graduate Institute in Carpinteria, California. The library includes Gimbutas' extensive collection on the topics of archaeology, mythology, folklore, art and linguistics. The Gimbutas Archives house over 12,000 images personally taken by Gimbutas of sacred figures, as well as research files on Neolithic cultures of Old Europe.[14]

Doctorate

In 1946, Marija Gimbutas received her PhD in Archeology & Applied Sciences from the University of Tübingen, Germany. Her doctoral dissertation was titled, "Die Bestattung in Litauen in der vorgeschichtlichen Zeit" ("Burials in Lithuania in Prehistoric Times") and was published by J.C.B. Mohr, Germany[15]. She often said that she had the dissertation under one arm and her child under the other arm when she and her husband evacuated the city of Kaunas, Lithuania in the face of an advancing Soviet army in 1944.

In 1993, Marija Gimbutas received an honorary doctorate at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, Lithuania.

Influence

Gimbutas's theories have been extended and embraced by a number of neopaganism authors. Gimbutas did identify the diverse and complex Paleolithic and Neolithic female representations she recognized as depicting a single universal Great Goddess, but also as manifesting a range of female deities: snake goddess, bee goddess, bird goddess, mountain goddess, Mistress of the Animals, etc., which were not necessarily ubiquitous throughout Europe.

In a tape entitled "The Age of the Great Goddess," Gimbutas discusses the various manifestations of the Goddess which occur, and stresses the ultimate unity behind them: all of the Earth as feminine.

In 2003, filmmaker Donna Read and neopagan author and activist Starhawk released a collaborative documentary film about the life and work of Gimbutas, Signs Out of Time. The film produced under the label Belili Productions examines "her theories, her critics, and her influence on scholars, feminists and social thinkers." (From cover of DVD)

Assessment

Praise

Joseph Campbell and Ashley Montagu[16][17] each compared the importance of Marija Gimbutas' output to the historical importance of the Rosetta Stone in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. Campbell provided a foreword to a new edition of Gimbutas' The Language of the Goddess (1989) before he died, and often said how profoundly he regretted that her research on the Neolithic cultures of Europe had not been available when he was writing The Masks of God. The ecofeminist Charlene Spretnak argued in 2011 that a "backlash" against Gimbutas' work had been orchestrated, starting in the last years of her life and following her death.[18]

Criticism

Mainstream archaeology dismissed Gimbutas' later works.[19] Anthropologist Bernard Wailes (1934–2012) of the University of Pennsylvania commented to The New York Times that most of Gimbutas's peers[20] believe her to be "immensely knowledgeable but not very good in critical analysis. ... She amasses all the data and then leaps from it to conclusions without any intervening argument." He said that most archaeologists consider her to be an eccentric.[17]

David Anthony has praised Gimbutas's insights regarding the Indo-European Urheimat, but also disputed Gimbutas's assertion that there was a widespread peaceful society before the Kurgan incursion, noting that Europe had hillforts and weapons, and presumably warfare, long before the Kurgan.[17] A standard textbook of European prehistory corroborates this point, stating that warfare existed in neolithic Europe and that adult males were given preferential treatment in burial rites.[21]

Peter Ucko and Andrew Fleming were two early critics of the "Goddess" theory, with which later Gimbutas came to be associated. Ucko, in his 1968 monograph Anthropomorphic figurines of predynastic Egypt warned against unwarranted inferences about the meanings of statues. Ucko, for example, notes that early Egyptian figurines of women holding their breasts had been taken as "obviously" significant of maternity or fertility, but the Pyramid Texts revealed that in Egypt this was the female sign of grief.[22]

Fleming, in his 1969 paper "The Myth of the Mother Goddess", questioned the practice of identifying neolithic figures as female when they weren't clearly distinguished as male and took issue with other aspects of the "Goddess" interpretation of Neolithic stone carvings and burial practices.[23]

The 2009 book Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism by Cathy Gere examines the political influence on archaeology more generally. Through the example of Knossos on the island of Crete, which had been misrepresented as the paradigm of a pacifist, matriarchal and sexually free society, Gere claims that archaeology can easily slip into reflecting what people want to see, rather than teaching people about an unfamiliar past.[24] [25]

Bibliography

Monographs

- Gimbutas, Marija (1946). Die Bestattung in Litauen in der vorgeschichtlichen Zeit. Tübingen: H. Laupp.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1956). The Prehistory of Eastern Europe. Part I: Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age Cultures in Russia and the Baltic Area. American School of Prehistoric Research, Harvard University Bulletin No. 20. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum.

- Gimbutas, Marija & R. Ehrich (1957). COWA Survey and Bibliography, Area – Central Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1958). Ancient symbolism in Lithuanian folk art. Philadelphia: American Folklore Society, Memoirs of the American Folklore Society 49.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1958). Rytprusiu ir Vakaru Lietuvos Priesistorines Kulturos Apzvalga [A Survey of Prehistory of East Prussia and western Lithuania]. New York: Studia Lituaica I.

- Gimbutas, Marija & R. Ehrich (1959). COWA Survey and Bibliography, Area 2 – Scandinavia. Cambridge: Harvard University.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1963). The Balts. London : Thames and Hudson, Ancient peoples and places 33.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1965). Bronze Age cultures in Central and Eastern Europe. The Hague/London: Mouton.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1971). The Slavs. London : Thames and Hudson, Ancient peoples and places 74.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1974). Obre and Its Place in Old Europe. Sarajevo: Zemalski Museum. Wissenchaftliche Mitteilungen des Bosnisch-Herzogowinischen Landesmuseums, Band 4 Heft A.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1974). The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe, 7000 to 3500 BC: Myths, Legends and Cult Images. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1981). Grotta Scaloria: Resoconto sulle ricerche del 1980 relative agli scavi del 1979. Manfredonia: Amministrazione comunale.

- Gimbutienė, Marija (1985). Baltai priešistoriniais laikais : etnogenezė, materialinė kultūra ir mitologija. Vilnius: Mokslas.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1989). The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1991). The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe. San Francisco: Harper.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1992). Die Ethnogenese der europäischen Indogermanen. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, Vorträge und kleinere Schriften 54.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1994). Das Ende Alteuropas. Der Einfall von Steppennomaden aus Südrussland und die Indogermanisierung Mitteleuropas. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft.

- Gimbutas, Marija, edited and supplemented by Miriam Robbins Dexter (1999) The Living Goddesses. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Edited volumes

- Gimbutas, Marija (ed.) (1974). Obre, Neolithic Sites in Bosnia. Sarajevo: A. Archaeologic.

- Gimbutas, Marija (ed.) (1976). Neolithic Macedonia as reflected by excavation at Anza, southeast Yugoslavia. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Monumenta archaeologica 1.

- Renfrew, Colin, Marija Gimbutas and Ernestine S. Elster (1986). Excavations at Sitagroi, a prehistoric village in northeast Greece. Vol. 1. Los Angeles : Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Monumenta archaeologica 13.

- Gimbutas, Marija, Shan Winn and Daniel Shimabuku (1989). Achilleion: a Neolithic settlement in Thessaly, Greece, 6400-5600 B.C. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles. Monumenta archaeologica 14.

Articles

- 1960: “Culture Change in Europe at the Start of the Second Millennium B.C. A Contribution to the Indo-European Problem”, Selected Papers of the Fifth International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. Philadelphia, September 1–9, 1956, ed. A.F.C. Wallace. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1960, pp. 540–552.

- 1961: “Notes on the chronology and expansion of the Pit-grave culture”, L’Europe à la fin de l’Age de la pierre, eds., J. Bohm & S. J. De Laet. Prague: Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, 1961, pp. 193–200.

- 1963: “The Indo-Europeans, archaeological problems”, American Anthropologist 65 (1963): 815–836.

- 1970: “Proto-Indo-European Culture: The Kurgan Culture during the Fifth, Fourth, and Third Millennia B.C.”, Indo-European and Indo-Europeans. Papers Presented at the Third Indo-European Conference at the University of Pennsylvania, ed. George Cardona, Henry M. Hoenigswald & Alfred Senn. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970, pp. 155–197.

- 1973: “Old Europe c. 7000–3500 BC: The Earliest European Civilization Before the Infiltration of the Indo-European Peoples”, Journal of Indo-European Studies (JIES) 1 (1973): 1–21.

- 1977: “The First Wave of Eurasian Steppe Pastoralists into Copper Age Europe”, JIES 5 (1977): 277–338.

- "Gold Treasure at Varna”, Archaeology 30, 1 (1977): 44–51.

- 1979: “The Three Waves of Kurgan People into Old Europe, 4500–2500 BC”, Archives suisses d’anthropologie genérale. 43-2 (1979): 113–137.

- 1980: “The Kurgan wave #2 (c.3400–3200 BC) into Europe and the following transformation of culture”, JIES 8 (1980): 273–315.

- “The Temples of Old Europe”, Archaeology 33-6 (1980): 41–50.

- 1980–81: “The transformation of European and Anatolian culture c. 4500-2500 B.C. and its legacy”, JIES 8 (I-2), 9 (I-2).

- 1982: “Old Europe in the Fifth Millennium B.C.: The European Situation on the Arrival of Indo-Europeans”, The Indo-Europeans in the Fourth and Third Millennia BC, ed. Edgar C. Polomé. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers, 1982, pp. 1–60.

- “Women and Culture in Goddess-oriented Old Europe”, The Politics of Women’s Spirituality, ed. Charlene Spretnak. New York: Doubleday, 1982, pp. 22–31.

- “Vulvas, Breasts, and Buttocks of the Goddess Creatress: Commentary on the Origins of Art”, The Shape of the Past: Studies in Honor of Franklin D. Murphy, eds. Giorgio Buccellati & Charles Speroni. Los Angeles: UCLA Institute of Archaeology, 1982.

- 1985: “Primary and Secondary Homeland of the Indo-Europeans: Comments on Gamkrelidze-Ivanov Articles”, JIES 13:1–2 (1985): 185–202.

- 1986: “Kurgan Culture and the Horse”, critique of the article “The ‘Kurgan Culture’, Indo-European origins and the domestication of the horse: a reconsideration” by David W. Anthony (same issue, pp. 291–313), Current Anthropology 27-4 (1986): 305–307.

- “Remarks on the ethnogenesis of the Indo-Europeans in Europe”, Ethnogenese europäischer Völker, eds. W. Bernhard & A. Kandler-Palsson. Stuttgart / New York: Gustav Fische Verlag, 1986: 5–19.

- 1987: “The Pre-Christian Religion of Lithuania”, La Cristianizzazione della Lituania. Rome, 1987.

- “The Earth Fertility of old Europe”, Dialogues d’histoire ancienne, vol. 13, no. 1 (1987): 11-69.

- 1988: “A Review of Archaeology and Language by Colin Renfrew”, Current Anthropology 29-3 (Jul 1988): 453–456.

- “Accounting For a Great Change, critique of Archaeology and Language by C. Renfrew”, London Times Literary Supplement (Jun 24–30), 1988, p. 714.

- 1990: “The Social Structure of the Old Europe. Part II”, JIES 18 (1990): 225–284.

- “The Collision of Two Ideologies”, When Worlds Collide: Indo-Europeans and Pre-Indo-Europeans, eds. T.L. Markey & A.C. Greppin. Ann Arbor (MI): Kasoma, 1990, pp. 171–8.

- “Wall Paintings of Çatal Hüyük, 8th–7th Millenia B.C.”, The Review of Archaeology, 11/2 (1990): 1–5.

- 1992: “The Chronologies of Eastern Europe: Neolithic through Early Bronze Age”, Chronologies in Old World Archaeology, vol. 1, ed. R.W. Ehrich. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press, 1992, pp. 395–406.

- 1993: “The Indo-Europeanization of Europe: the intrusion of steppe pastoralists from south Russia and the transformation of Old Europe”, Word 44 (1993): 205–222.

Collected articles

- Dexter, Miriam Robbins and Karlene Jones-Bley (eds) (1997). The Kurgan culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected articles from 1952 to 1993 by M. Gimbutas. Journal of Indo-European Studies monograph 18. Washington DC: Institute for the Study of Man.

Studies in honor

- Skomal, Susan Nacev & Edgar C. Polomé (eds) (1987). Proto-Indo-European: The Archaeology of a Linguistic Problem. Studies in Honor of Marija Gimbutas. Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man.

- Marler, Joan, ed. (1997). From the Realm of the Ancestors: An Anthology in Honor of Marija Gimbutas. Manchester, CT: Knowledge, Ideas & Trends, Inc.

- Dexter, Miriam Robbins and Edgar C. Polomé, eds. (1997). Varia on the Indo-European Past: Papers in Memory of Gimbutas, Marija. Journal of Indo-European Studies Monograph #19. Washington, DC: The Institute for the Study of Man.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ware & Braukman 2004, p. 234.

- ↑ Marler 1998, p. 114.

- 1 2 Marler 1998, p. 115.

- ↑ Marler 1998, p. 116.

- ↑ Marler 1997, p. 9.

- ↑ Ware & Braukman 2004, pp. 234–235.

- 1 2 3 Ware & Braukman 2004, p. 235.

- ↑ Marler 1998, p. 118.

- ↑ Chapman 1998, p. 300.

- ↑ Marler 1998, p. 119.

- ↑ Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, Haak et al, 2015

- ↑ Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia, Allentoft et al, 2015

- ↑ Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe, Mathieson et al, 2015

- ↑ http://www.opusarchives.org/gimbutas_overview.shtml

- ↑ Marija Gimbutas' doctoral dissertation listed in the University of Tubingen Catalog https://katalog.ub.uni-tuebingen.de/opac/RDSRecord/RDSDetails?id=010331530

- ↑ "According to anthropologist Ashley Montagu, "Marija Gimbutas has given us a veritable Rosetta Stone of the greatest heuristic value for future work in the hermeneutics of archaeology and anthropology." "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2004-02-04. Retrieved 2004-02-19.

- 1 2 3 Peter Steinfels (1990) Idyllic Theory Of Goddesses Creates Storm. NY Times, February 13, 1990

- ↑ Spretnak C., (2011), in Marler J. and Haarmann H., (eds.), "Anatomy of a Backlash: Concerning the Work of Marija Gimbutas", J. of Archaeomythology, 7: 1–27, ISSN 2162-6871

- ↑ Paul Kiparsky, "New perspectives in historical linguistics", To appear in Claire Bowern (ed.)Handbook of Historical Linguistics.

- ↑ The New York Times book of science literacy: what everyone needs to know from Newton to the knuckleball, page 85, Richard Flaste, 1992

- ↑ S. Milisauskas, European prehistory (Springer, 2002), p.82, 386, etc. See also Colin Renfrew, ed., The Megalithic Monuments of Western Europe: the latest evidence (London : Thames and Hudson, 1983).

- ↑ P. Ucko, Anthropomorphic figurines of predynastic Egypt and neolithic Crete with comparative material from the prehistoric Near East and mainland Greece (London, A. Szmidla, 1968).

- ↑ A. Fleming (1969), "The Myth of the Mother Goddess", World Archaeology 1(2), 247–261.

- ↑ Cathy Gere (2009), Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism, University of Chicago Press, pp. 4-16ff.

- ↑ See also Charlotte Allen, "The Scholars and the Goddess.", The Atlantic Monthly, January 1, 2001.

Further reading

- Chapman, John (1998), "The impact of modern invasions and migrations on archaeological explanation: A biographical sketch of Marija Gimbutas", in Díaz-Andreu, Margarita; Sørensen, Marie Louise Stig, Excavating Women: A History of Women in European Archaeology, New York: Routledge, pp. 295–314, ISBN 0-415-15760-9.

- Elster, Ernestine S. (2007). “Marija Gimbutas: Setting the Agenda”, in Archaeology and Women: Ancient and Modern Issues, eds. Sue Hamilton, Ruth D. Whitehouse, and Katherine I. Wright. Left Coast Press (reprint Routledge, 2016).

- Häusler, Alexander (1995), "Über Archäologie und den Ursprung der Indogermanen", in Kuna, Martin; Venclová, Natalie, Whither archaeology? Papers in honour of Evzen Neustupny, Prague: Institute of Archaeology, pp. 211–229, ISBN 80-901934-0-4.

- Marler, Joan (1997), Realm of the Ancestors: An Anthology in Honor of Marija Gimbutas, Manchester, Connecticut: Knowledge, Ideas & Trends, ISBN 1-879198-25-8.

- Marler, Joan (1998), "Marija Gimbutas: Tribute to a Lithuanian Legend", in LaFont, Suzanne, Women in Transition: Voices from Lithuania, Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-3811-2.

- Meskell, Lynn (1995), "Goddesses, Gimbutas and 'New Age' Archaeology", Antiquity, 69: 74–86.

- Murdock, Maureen (2014), "Gimbutas, Marija, and the Goddess", Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion, 2nd edn., ed. David A. Leeming. NY–Heidelberg–Dordrecht–London: Springer, pp. 705–10.

- Spretnak, Charlene (2011), Marler, Joan; Haarmann, Harald, eds., "Anatomy of a Backlash: Concerning the Work of Marija Gimbutas" (PDF), Journal of Archaeomythology, 7: 1–27, ISSN 2162-6871, retrieved 2014-06-24

- Ware, Susan; Braukman, Stacy Lorraine (2004), Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01488-X.