Marietta, Ohio

| Marietta, Ohio | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Downtown Marietta in July 2007, including the Muskingum River (foreground) and the Ohio River (background right) | |

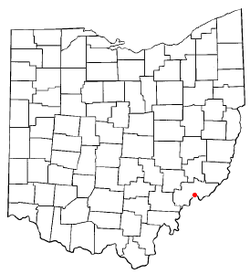

Location of Marietta in Ohio | |

Location of Marietta in Washington County | |

| Coordinates: 39°25′N 81°27′W / 39.417°N 81.450°WCoordinates: 39°25′N 81°27′W / 39.417°N 81.450°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Washington |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Joe Mathews (D) |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 8.75 sq mi (22.66 km2) |

| • Land | 8.43 sq mi (21.83 km2) |

| • Water | 0.32 sq mi (0.83 km2) |

| Elevation[2] | 614 ft (187 m) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • Total | 14,085 |

| • Estimate (2012[4]) | 14,027 |

| • Density | 1,670.8/sq mi (645.1/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP code | 45750 |

| Area code(s) | 740, 220 |

| FIPS code | 39-47628[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1076339[2] |

| Website | http://www.mariettaoh.net/ |

Marietta is a city in and the county seat of Washington County, Ohio, United States.[6] During 1788, pioneers to the Ohio Country established Marietta as the first permanent settlement of the new United States in the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio. Marietta is located in southeastern Ohio at the mouth of the Muskingum River at its confluence with the Ohio River. The population was 14,085 at the 2010 census.

It is the second-largest city in the Parkersburg-Marietta-Vienna, WV-OH Combined Statistical Area. The private, nonsectarian liberal arts Marietta College is located here. It was a station on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War. Marietta is also the site of the prehistoric Marietta Earthworks, a Hopewell complex more than 1500 years old, whose Great Mound and other major monuments were preserved by the earliest settlers in parks such as the Mound Cemetery.

Geography

Marietta is located at 39°25′15″N 81°27′2″W / 39.42083°N 81.45056°W (39.420824, −81.450506).[7]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.75 square miles (22.66 km2), of which 8.43 square miles (21.83 km2) is land and 0.32 square miles (0.83 km2) is water.[1]

The Muskingum River and Duck Creek flow into the Ohio River at Marietta. The area is part of the Appalachian Plateau which covers the eastern half of Ohio. The Appalachian Plateau consists of steep hills and valleys and is the most rugged area in the state. The area is within the ecoregion of the Western Allegheny Plateau.[8] This portion of the state is blessed with beautiful scenery and Ohio's most abundant mineral deposits.[9]

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by humid summers, cold winters, and evenly distributed precipitation throughout the year. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Marietta has a Humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfa" on climate maps.[10]

History

Prehistoric

Succeeding Indian cultures lived along the Ohio River and its tributaries for thousands of years. Among them were more than one culture who built earthwork mounds, monuments which generally expressed their cosmology, often with links to astronomical events.

Between 100 BC and AD 500, the Hopewell culture built the multi-earthwork complex on the terrace east of the Muskingum River near its mouth with the Ohio. It is now known as the Marietta Earthworks. Developed over many years, it had a large enclosed square, within which were four platform mounds, used for ceremonial purposes and elite residential; another square, and a larger conical mound used for burials. A walled, graded path led to the river's edge.[11] By the time of the historic tribes, such as the Shawnee, the purposes and makers of the monuments were no longer known.

Settlement

French explorers entered this area in the 18th century, and in 1749 buried numerous leaden plates to mark their claim to the Ohio Country (which they called the Illinois Territory, as they had more settlements near the Mississippi River.) They later ceded their territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain after the French and Indian War. Two of their plates were discovered in the Marietta area in 1798, and one was replicated for what is known as the French monument, erected in the 20th century. (See photo at right.)

In 1770, the future U.S. president George Washington, then a surveyor, began exploring large tracts of land west of his native Virginia. During the Revolutionary War, Washington told his friend General Rufus Putnam of the beauty he had seen in his travels through the Ohio Valley and of his ideas for settling the territory.

After the American Revolutionary War, the United States sold or granted large tracts of land to stimulate development in this area. Marietta was founded by settlers from New England who were investors in the Ohio Company of Associates.[12] It was the first of numerous New England settlements in what was then the Northwest Territory.[13] These New Englanders, or "Yankees" as they were called, were descended from the Puritan English colonists who had settled New England in the 1600s and were primarily Congregationalists. The first church constructed in Marietta was a Congregationalist church, founded around 1786.[13] Before the mid-1790s services were held at the fort or in Munsell's Hall at nearby Point Harmar. In 1798 the Muskingum Academy was built on the site of the 19th century Marietta Congregationalist Church. The academy building served for both educational and religious purposes.[14]

In the summer of 1781, John Carpenter built Carpenter's Fort, or Carpenter's Station as it was sometimes called, a fortified house above the mouth of Short Creek on the Ohio side of the Ohio River, near present-day Marietta.[15][16]

After the war, the newly formed United States had little cash but plenty of land. Eager to develop additional lands, the new government decided to pay veterans of the Revolution with warrants for land in the Northwest Territory, which was organized under federal authority in 1787 by the Northwest Ordinance. Competing states had agreed to end their claims to the lands; Pennsylvania and Virginia received some lands in a settlement. Arthur St. Clair was appointed by the president as governor of the new territory.

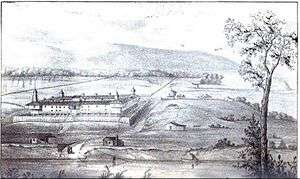

The Ohio Company of Associates had supported provisions in the ordinance to allow veterans to use their warrants to purchase the land. They bought 1.5 million acres (6,100 km²) of land from Congress. On April 7, 1788, 48 men of the Ohio Company of Associates, led by General Putnam, arrived at the confluence of the Muskingum and Ohio rivers. The site was on the east side of the Muskingum River, across from Fort Harmar, a military outpost built three years prior.

Bringing with them the first government sanctioned by the US for this area,[17] they established the first permanent United States settlement in the Northwest Territory.[18][19] (Older European settlements in the Northwest Territory region include Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, 1668; Detroit, 1701; Prairie du Rocher, Illinois, 1720; and Vincennes, Indiana, 1732, all settled by ethnic French colonists from Canada.) The Americans named Marietta in honor of Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France, who had aided the colonies in their battle for independence from Great Britain.

The Indians were unhappy to see white settlers moving into their territory. The latter immediately started construction of two forts: Campus Martius, whose former site is now occupied by the museum of the same name, and Picketed Point Stockade, at the confluence of the Muskingum and Ohio rivers. At the same time, the settlers started developing their community, platted according to plans they had made in Boston.

In 1788, George Washington said,

"No colony in America was ever settled under such favorable auspices as that which has just commenced at the Muskingum. ... If I was a young man, just preparing to begin the world, or if advanced in life and had a family to make provision for, I know of no country where I should rather fix my habitation...".[20]

The families of the settlers began arriving within a few months. By the end of 1788, 137 people populated the area.

In 1789, the United States signed the Treaty of Fort Harmar with several Indian tribes that occupied areas of the Northwest Territory, to settle issues related to trade, as well as the boundary between their lands and United States settlement. The US did not address the Indians' major grievance about American settlers moving into their lands, particularly in the Western Reserve, where there were disputes over land. Although Congress authorized Governor Arthur St. Clair to give land back to the Indians, he did not do so. Conflict increased as the Indians tried to push the settlers out. After years of warfare in the region, they were defeated. The US signed the Treaty of Greenville (1795) with the Indians, which secured the safety of settlers to leave the forts and develop their farms.

The settlers held services regularly and chartered the first church in 1796. It was a Congregational institution; its charter was unusually inclusive due to the varied religious backgrounds of its members. The congregation constructed the first church building in 1807.[13]

Education was important to the settlers, many of whom had been officers during the Revolution. During that first winter, they began a basic school for the children at Campus Martius. In 1797, settlers founded Muskingum Academy. The town had numerous abolitionists, and Ephraim Cutler was instrumental as a state delegate in 1802 at the state convention in swaying the vote for the state to be free of slavery.[21]

19th century

Townspeople organized and chartered Marietta College in 1835. It was used as a station on the Underground Railroad to help slaves escape from the South.[21] Ohio University was founded earlier in Athens, on land reserved for public education under the Northwest Ordinance.

The settlers preserved the Great Mound, or Conus, by planning their own cemetery around it. They also preserved the two largest platform mounds, which they called Capitolinus and Quadrophenus. The former was developed as the site for the city library.[11] As of 1900, the Mound Cemetery had the highest number of burials of Revolutionary War officers in the nation, indicating the nature of the generation that settled Marietta.[22]

Marietta's location on two major navigable rivers made it ideal for industry and commerce. Boat building was one of the early industries. Artisans built oceangoing vessels and sailed them downriver to the Mississippi and south to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. In less than two decades after settlement, the steamboat had been developed, and was also constructed here. Brick factories and sawmills supplied materials for homes and public buildings. An iron mill, along with several foundries, provided rails for the growing railroad industry; the Marietta Chair Factory made furniture.

Interest in the prehistoric culture that built the Marietta Earthworks continued. The complex was surveyed and drawn by Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, whose large project on numerous prehistoric mounds throughout the Ohio and Mississippi valleys was published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1848 as Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. It was the first book published by the Smithsonian. Their drawing to the right shows the plan of the original complex, which "included a large square enclosure surrounding four flat-topped pyramidal mounds, another smaller square, and a circular enclosure with a large burial mound at its center."[11] The walled, graded path, called by the settlers the Sacra Via, led from the largest enclosure to the lower river's edge. This pathway was destroyed in 1843 during mid-nineteenth century development.[11]

Railroads and oil

Local development began with the Belpre and Cincinnati Railroad (B&C); it was founded in 1845. It was intended to connect from Belpre, Ohio, the next town downriver, to a planned Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) spur to Parkersburg. But, for years, the Virginia government did not allow the B&O to construct track south of Wheeling. In 1851 developers changed the Ohio state terminus to Marietta and changed the name of the railroad to the Marietta and Cincinnati Railroad that year. The right-of-way for an alternate connection to the B&O extended upriver from Marietta to Bellaire, Ohio. The M&C was bankrupt by 1857, but construction of track continued west to reach Cincinnati. The first through-train from Cincinnati ran on April 9, 1857. The M&C got out of bankruptcy in 1860.

In 1871, the Ohio Valley Railroad was formed and for the next two years built tracks going north for 103 miles. Their home office was in Marietta, with treasurer offices in Pittsburgh. The Ohio Valley railroad was reorganized as the Marietta and Cleveland. The Pennsylvania Railroad in its expansion later purchased the railroad and its right-of-way between Marietta and Bellaire.

Passengers traveling between Marietta and Parkersburg, Virginia (now West Virginia) had to take a steamboat for the 14 miles between the two towns and transfer. With help from the B&O and the Baltimore City Council, the Union Railroad finally connected Marietta to Belpre, Ohio in 1860. Later absorbed by the B&O, this section of track is still in operation (2008), with unit coal trains providing most of the traffic.

The planned bridge from Parkersburg across the Ohio River to Belpre was finally built 1868–1870 by the B&O, as part of its main line from Baltimore to St. Louis, Missouri.[23] This cut Marietta off from traffic and trade, although it retained local and Ohio service. In the early 20th century, 24 passenger trains served Marietta each day, most of which ran on the PRR tracks.

William P. Cutler was a major figure in the M&C. He also backed the Union Railroad and the Marietta, Columbus and Cleveland Railroad, among other local railroads. Cutler served as General Manager and as President of the M&C for many years.

In 1860, oil was first drilled in the Marietta region. Oil booms in 1875 and 1910 made investors rich, who constructed numerous lavish houses in town, of which many still stand.[24] The Dawes brothers of Marietta founded the Pure Oil Company. All four brothers became nationally prominent businessmen and/or politicians: Charles Gates Dawes, Rufus C. Dawes, Beman Gates Dawes and Henry May Dawes. Charles Dawes was elected in 1924 with President Calvin Coolidge to serve as the 30th Vice President of the United States (1925–1929). In 1925, he shared the Nobel Peace Prize, based on his work on the Dawes Plan and relieving an international crisis in 1923 related to German reparations after World War I.

In 1880, the first Putnam Street Bridge was opened to connect Marietta to Fort Harmar. It provided the first free crossing of the Muskingum River.

20th century

As transportation advanced along railroads and highways, Marietta was initially passed by. From 1868–1870, the B & O Railroad built a bridge to connect Parkersburg, West Virginia and Belpre; and the National Road went further north through Zanesville.

But, the Pennsylvania Railroad expanded in the late 19th century and had a station in Marietta, running 26 daily trains between Marietta and Pittsburgh. After WWII passenger service decreased as the railroads restructured and the federal government invested in highway construction. The last rail passenger service ended in 1953. Marietta was relatively isolated from new travel routes until 1967, when I-77 was opened with close access to the city.

Before the United States entered the Great War, a group of 23 young men went from Marietta College to serve in French in 1917 as an ambulance unit; four died in battle. In 1937–1938, during the US celebration of the Northwest Territory, France gave a plaque to the city of Marietta, which was installed on the French monument, to commemorate these young men and their service. (See photo at right.)

In 1939, the Sons and Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen was established in Marietta during the Great Depression to celebrate the city's substantial river history and its people. Two years later the Ohio River Museum was opened. In 1972, the museum campus was totally redesigned.

Economy

Marietta is home of the longest-running ferromanganese refinery in North America, Eramet Marietta Industries Inc., the only ferromanganese refinery in the United States until recently, and leader in Manganese emissions.[25]

Government

Local government

The city of Marietta uses the mayor-council form of government. The mayor is a full-time position; the seven city council members and the city council president are all part-time positions. The city is divided into four single-member districts or wards, with a person from each ward elected to the council. In addition, there is election at-large of a non-voting city council president and three voting councilmen.

Michael "Moon" Mullen, a Democrat, is the current mayor of Marietta. He followed Democrat Joseph Matthews after defeating him in the 2003 Democratic primary. Before becoming mayor, Mullen was an at-large member of city council. He had served the first ward on the council and as the Marietta City Development Director. On November 2, 2003, Mullen was elected mayor after defeating Republican challenger Cathy Harper and independent candidate Dan Harrison. Mullen took office in January 2004, and was reelected in 2007.

Al Miller is the current Safety Service Director of Marietta. He was appointed by Mullen in January 2011.

In 2007, no Republican candidate filed for the position of mayor. The former mayor Joe Matthews challenged Mayor Mullen for the Democratic nomination, but was defeated in the May 8th primary 55%–45%. 2003 Mayoral Candidate Dan Harrison filed to run for City Council President as an Independent. When it was found that he had voted in the Democratic primary, his Independent status was voided, so his name was removed from the ballot. In the November 6th general election, Mullen defeated two independent candidates, Chris Hansis and Rich Hudson. Mullen took 63.15% of the vote. Hansis, a 26-year-old newcomer to politics, took 27.13%, and Hudson, owner of a local store, took 9.72%.

| City Council of Marietta, Ohio (2008–2010 term) | ||

| Council President | Paul Bertram III | Republican |

| At-Large | Harley Noland | Democrat |

| At-Large | Denver Abicht | Democrat |

| At-Large | Josh Schlicher | Republican |

| First Ward | David White | Republican |

| Second Ward | Mike McCauley | Democrat |

| Third Ward | Jon Grimm | Republican |

| Fourth Ward | Tom Vukovic | Democrat |

With the retirements and electoral decisions, Marietta will have a council on which at least half of the eight Council positions will be held by new officeholders.

After winning a majority of council seats in the 2007 elections, the Republican Party lost that majority in 2009. Mike McCauley, a former Republican who switched parties to run as a Democrat, defeated the Ward 2 incumbent Randy Wilson. The City Council and City Hall are under control of the Democratic Party.

City of Marietta politics feature a number of citizens groups that influence policy and public opinion. Such groups as Citizens for Responsible Government, the Citizen's Armory Preservation Society, and Neighbors for Clean Air work to improve the public process. exercise significant influence over the government of the city.

State and federal government

The residents of the city of Marietta are represented by former Council-at-Large Republican Andy Thompson in the Ohio House of Representatives and Republican Jimmy Stewart in the Ohio Senate. Senator Stewart won the 2008 election after defeating Democrat Rick Shriver.

In the U.S. House of Representatives, Marietta is represented by Republican Bill Johnson.

Transportation

Highways

Interstates

Interstate 77 runs east of Marietta connecting it to Cleveland, Ohio to the north and Charleston, West Virginia to the south.

State Routes

Five state routes run through Marietta. These are; Ohio State Route 7, Ohio State Route 60, Ohio State Route 26, Ohio State Route 550, and Ohio State Route 676.

Air

Marietta is served by Mid-Ohio Valley Regional Airport in Williamstown, West Virginia which has 3 flights a day Monday Through Friday from Charlotte Douglas International Airport.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 321 | — | |

| 1810 | 463 | 44.2% | |

| 1820 | 746 | 61.1% | |

| 1830 | 1,207 | 61.8% | |

| 1840 | 1,814 | 50.3% | |

| 1850 | 3,175 | 75.0% | |

| 1860 | 4,323 | 36.2% | |

| 1870 | 5,218 | 20.7% | |

| 1880 | 5,444 | 4.3% | |

| 1890 | 8,273 | 52.0% | |

| 1900 | 13,348 | 61.3% | |

| 1910 | 12,923 | −3.2% | |

| 1920 | 15,140 | 17.2% | |

| 1930 | 14,285 | −5.6% | |

| 1940 | 14,543 | 1.8% | |

| 1950 | 16,006 | 10.1% | |

| 1960 | 16,847 | 5.3% | |

| 1970 | 16,861 | 0.1% | |

| 1980 | 16,467 | −2.3% | |

| 1990 | 15,026 | −8.8% | |

| 2000 | 14,515 | −3.4% | |

| 2010 | 14,085 | −3.0% | |

| Est. 2016 | 13,650 | [26] | −3.1% |

| Sources:[5][27][28][29] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 14,085 people, 5,828 households, and 3,215 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,670.8 inhabitants per square mile (645.1/km2). There were 6,519 housing units at an average density of 773.3 per square mile (298.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.9% White, 1.3% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.4% Asian, 0.5% from other races, and 1.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.1% of the population.

There were 5,828 households of which 25.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.9% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 44.8% were non-families. 37.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.14 and the average family size was 2.80.

The median age in the city was 39 years. 18.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 16% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 21.1% were from 25 to 44; 25.7% were from 45 to 64; and 18.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 46.9% male and 53.1% female.

2000 census

As of the census[5] of 2000, there were 14,515 people, 5,904 households, and 3,501 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,747.0 people per square mile (674.4/km²). There were 6,609 housing units at an average density of 795.4 per square mile (307.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 96.31% White, 1.08% African American, 0.46% Native American, 0.71% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.28% from other races, and 1.11% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.79% of the population.

There were 5,904 households out of which 27.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.4% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.7% were non-families. 35.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.21 and the average family size was 2.86.

In the city the population was spread out with 20.9% under the age of 18, 14.0% from 18 to 24, 25.1% from 25 to 44, 22.3% from 45 to 64, and 17.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females there were 87.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,272, and the median income for a family was $36,042. Males had a median income of $30,683 versus $22,085 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,021. About 13.6% of families and 16.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.6% of those under age 18 and 10.4% of those age 65 or over.

Environmental issues

Eramet has released thousands of pounds of manganese and other hazardous air pollutants into the air.[30][25]

Notable people

- Founding pioneers, including Gen. Rufus Putnam, Gen. Benjamin Tupper, Gen. James Varnum, Gen. Samuel Holden Parsons, Commodore Abraham Whipple, Col. William Stacy, Griffin Greene, and other notable pioneers.[17][18][19][31]

- Levi Barber, was a surveyor, court administrator, banker, and member of the Ohio House of Representatives, Fifteenth United States Congress, & Seventeenth United States Congress[32]

- Dewey F. Bartlett, 19th Governor of Oklahoma, United States Senator[33]

- Hobart Bosworth, movie actor, director, writer and producer.

- John Brough, 26th Governor of Ohio, Member of the Ohio House of Representatives[34]

- Clem S. Clarke, oilman and Republican politician from Shreveport, Louisiana; born in Marietta in 1897[35]

- William Cutler, Member of the Ohio House of Representatives[36]

- Charles G. Dawes, 30th Vice President of the United States

- Rufus Dawes, Union Brigadier General

- Larry Dickson, auto racer

- Charles H. Elston, member of the United States House of Representatives[37]

- Althea Flynt, pornographic model, and wife of magazine magnate, Larry Flynt

- Samuel Prescott Hildreth, pioneer physician, scientist, and historian

- Nancy Hollister, 66th Governor of Ohio, Lieutenant Governor of Ohio, member of the Ohio House of Representatives[38]

- Perley Brown Johnson, Member of the Ohio House of Representatives[39]

- Alf Landon, 26th Governor of Kansas, 1936 Republican Presidential Candidate[40]

- Francis B. Loomis, 25th United States Assistant Secretary of State

- Return Jonathan Meigs, Jr., 4th Governor of Ohio and 5th United States Postmaster General[41]

- C. William O'Neill, 59th Governor of Ohio, Speaker of the Ohio House of Representatives, Associate & Chief Justice of the Ohio Supreme Court, Attorney General of the State of Ohio[42]

- Harrison Gray Otis (publisher), Los Angeles Times

- Greg Pryor, former Major League Baseball infielder

- Warner Wing, Michigan jurist and legislator[43]

- George White, 52nd Governor of Ohio[44]

- William A. Whittlesey, former US Congressman

- Chief Zimmer, major league baseball player and manager[45]

Notable events

- Since 1975, the Ohio River Sternwheel Festival has been held on the weekend after Labor Day in September. 2005 was the 30th anniversary of the event, which attracts dozens of Sternwheelers to the banks of the Ohio River near downtown Marietta. The Festival includes performances from musical artists, Sternwheel races, and a large fireworks display; it attracts thousands of visitors from across the country.

- The Riverfront Roar powerboat races are held annually in July. The event includes Formula 2 and Formula 3 powerboat racing along the Ohio River.

- Marietta Civil War Reenactment is also held at the end of September. It includes Union and Confederate reenactors battling across the scenic Muskingum River.

- Goodfest is held at Goodfellows Park; this local music festival for teenagers features local musicians in a drug & alcohol-free environment.

- A number of rowing regattas are held throughout the spring. Chief among them Marietta High School's Ralph Lindamood Memorial Regatta and the Marietta Invitational Regatta hosted by Marietta College, which brings some of the nation's fastest college rowing programs to the Muskingum River. In the fall season, the "Head of the Muskingum" head race is held, again drawing rowing teams from across the country. The race is run over a 3–3.5 mile course starting in Devola, Ohio and ending at Marietta College's Lindamood-Van Voorhis Boathouse.

- The 2016 Ohio State of the State address was held at People's Bank Theater on April 6. The speech was given by governor John Kasich.

Sister cities

See also

References

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- 1 2 "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- ↑ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- 1 2 3 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Level III Ecoregions of Ohio". National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ http://www.netstate.com/states/geography/oh_geography.htm

- ↑ Climate Summary for Marietta, Ohio

- 1 2 3 4 "Marietta Earthworks", Ohio History Central, accessed 20 August 2012

- ↑

- 1 2 3 Lois Kimball Mathews, The Expansion of New England: The Spread of New England Settlement and Institutions to the Mississippi River, 1620–1865, page 175

- ↑ Dickinson,Rev. CE. A History of the First Congregational Church of Marietta. self-publ., 1896. 9–30

- ↑ J. A. Caldwell: History of Belmont and Jefferson Counties, Ohio, Historical Publishing Co., Wheeling, W.Va., 1880, p. 605, reprinted 1983.

- ↑ Julie Minot Overton, with Kay Ballantyne Hudson and Sunda Anderson Peters, eds.: Ohio Towns and Townships to 1900: A Location Guide, The Ohio Genealogical Society, Mansfield, Ohio: Penobscot Press, 2000, p. 59.

- 1 2 Hildreth, S. P.: Pioneer History: Being an Account of the First Examinations of the Ohio Valley, and the Early Settlement of the Northwest Territory, H. W. Derby and Co., Cincinnati, Ohio (1848)

- 1 2 Hulbert, Archer Butler: The Records of the Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company, Volume I, Marietta Historical Commission, Marietta, Ohio (1917).

- 1 2 Hulbert, Archer Butler: The Records of the Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company, Volume II, Marietta Historical Commission, Marietta, Ohio (1917). Note:

- ↑ Sparks, Jared: The Writings of George Washington, Vol. IX, Harper and Brothers, New York (1847) p. 385.

- 1 2 Robert C. Yeager, "A Historic River Town Where the West Began", New York Times, 6 November 2009, accessed 22 August 2012

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR): American Monthly, Vol. 16, Jan–Jun 1900, New York: R. R. Bowker Co., 1900, p. 329

- ↑ Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, Parkersburg Bridge, Ohio River, Parkersburg, Wood County, WV, Historic American Engineering Record, accessed 22 August 2012

- ↑ Yeager, Robert C. (November 6, 2009). "A Historic River Town Where the West Began". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- 1 2 Haynes EN, Heckel P, Ryan P, Roda S, et al. Environmental manganese exposure in residents living near a ferromanganese refinery in Southeast Ohio: a pilot study.Neurotoxicology. 2010 Sep;31(5):468-74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.10.011.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Number of Inhabitants: Ohio" (PDF). 18th Census of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Ohio: Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ Economic Impact Analysis (EIA) for the Manganese Ferroalloys RTR. EPA 2015, 68pp

- ↑ Summers, Thomas J.: History of Marietta, The Leader Publishing Co., Marietta, Ohio (1903).

- ↑ "BARBER, Levi, (1777–1833)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "BARTLETT, Dewey Follett, (1919–1979)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Ohio Governor John Brough". National Governors Association. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Historians Allan Nevins and Frank Ernest Hill. "Reminiscences of Clem S. Clarke: Oral history, 1951". New York City: Columbia University. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ↑ "CUTLER, William Parker, (1812–1889)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "ELSTON, Charles Henry, (1891–1980)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Ohio Governor Nancy P. Hollister". National Governors Association. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Biography of Perley Brown Johnson". Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ "Kansas Governor Alfred Mossman Landon". National Governors Association. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Ohio Governor Return Jonathan Meigs Jr.". National Governors Association. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Ohio Governor Crane William O'Neill". National Governors Association. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ 'History of Monroe County, Michigan,' volume I, John McClelland Bulkley, Lewis Publishing Company: 1913, Biographical Sketch of Warner Wing, pg. 259

- ↑ "Ohio Governor George White". National Governors Association. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Reichler, Joseph L., ed. (1979) [1969]. The Baseball Encyclopedia (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-578970-8.

- ↑ "Katrina: Marietta's sister city". August 28, 2010.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Marietta (Ohio). |

- Official city government website

- Marietta Area Chamber of Commerce website

- Convention and Visitors Bureau website

- WMOA, local radio station

- The Marietta Times, daily newspaper

- Chris Sandford, "Marietta Earthworks", Links to articles and early maps, hosted on University of Ohio faculty website