Delphine LaLaurie

| Delphine LaLaurie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Marie Delphine Macarty c. 1780 New Orleans, Spanish Louisiana Territory |

| Died |

7 December 1849 (aged 68–69)[1] Paris, France |

| Other names | Marie Delphine LaLaurie, Marie Delphine Macarty LaLaurie, Delphine Macarty LaLaurie , Delphine Maccarthy LaLaurie, Madame LaLaurie |

| Occupation | socialite |

| Known for | Torturing and killing of four black slaves, discovered in 1834 |

| Spouse(s) |

Don Ramón de Lopez y Angulo (married 1800 – died 1804) Jean Blanque (married 1808 – died 1816) Dr. Leonard Louis Nicolas LaLaurie (married 1825) |

| Children |

Marie-Borja/Borgia Delphine Lopez y Angulo de la Candelaria, nicknamed "Borquita" (daughter by Don Ramón de Lopez y Angulo) Marie Louise Pauline Blanque (daughter by Jean Blanque) Louise Marie Laure Blanque (daughter by Jean Blanque) Marie Louise Jeanne Blanque (daughter by Jean Blanque) Jeanne Pierre Paulin Blanque (son by Jean Blanque) |

Marie Delphine Macarty or MacCarthy (c. 1780 – 1849), more commonly known as Madame Blanque, until her third marriage and subsequent infamy remodeled her Madame LaLaurie, was a New Orleans Creole socialite and alleged serial killer, infamous for torturing and likely murdering her household slaves.

Born during the Spanish colonial period, Delphine Macarty married three times in Louisiana, having twice been widowed. She maintained her position in New Orleans society until April 10, 1834, when rescuers responded to a fire at her Royal Street mansion and discovered bound slaves in her attic who showed evidence of cruel, violent treatment over a long period. Lalaurie's house was subsequently sacked by an outraged mob of New Orleans citizens. She escaped to France with her family.[2]

The mansion where LaLaurie lived is a landmark in the French Quarter, in part because of its history and in part because there were relatively few homes of such massive size in the Quarter.

Early life and family history

Marie Delphine Macarty was born 1780, one of five children. Her father was Louis Barthelemy de McCarty, originally Chevalier de MacCarthy) whose father Barthelemy (de) MacCarthy brought the family to New Orleans from Ireland around 1730, during the French colonial period.[3] (The Irish surname MacCarthy was shortened to Macarty or de Macarty.) Her mother was Marie-Jeanne L'Erable, [4] also known as "the widow Le Comte", her marriage to Louis B. Macarty being her second.[3] Both were prominent in the town's white Creole community.[5] Delphine's Uncle, by marriage, Esteban Rodríguez Miró, was Governor of the Spanish American provinces of Louisiana and Florida during 1785–1791, and her cousin, Augustin de Macarty, was Mayor of New Orleans from 1815 to 1820.[6]

First marriage and death of husband

On June 11, 1800, Mlle. Marie Delphine Macarty married Don Ramón de Lopez y Angulo, a Caballero de la Royal de Carlos, a high-ranking Spanish royal officer,[5][7] at the Saint Louis Cathedral in New Orleans.[5] Luisiana, as it was spelled in Spanish, had become a Spanish colony in the 1760s. In 1804, after the American acquisition, Don Ramón had been appointed to the position of consul general for Spain in the Territory of Orleans.[5]

Also, in 1804, Delphine and Ramón Lopez traveled to Spain.[5] Accounts of the trip vary. Grace King wrote in 1921 that the trip was Lopez's "military punishment" and that Señora Delphine Lopez met the Queen, who was impressed with Mrs. Lopez's beauty.[8] Stanley Arthur's 1936 report differed; he stated that on March 26, 1804, Don Ramón Lopez was recalled to Spain "to take his place at court as befitting his new position," but that Lopez never arrived in Madrid because he died in en route, in Havana.[5]

During the voyage, Delphine gave birth to a daughter, named Marie-Borja/Borgia Delphine Lopez y Angulo de la Candelaria, nicknamed Borquita.[5][8] Delphine and her daughter returned to New Orleans afterwards.

Second marriage and death of husband

In June 1808, Delphine married Jean Blanque, a prominent banker, merchant, lawyer, and legislator.[5] At the time of the marriage, Blanque purchased a house at 409 Royal Street in New Orleans for the family, which became known later as the Villa Blanque.[5] Delphine had four more children by Blanque, named Marie Louise Pauline, Louise Marie Laure, Marie Louise Jeanne, and Jeanne Pierre Paulin Blanque.[5] Blanque died in 1816.[9]

Third marriage

Delphine married her third husband, physician Leonard Louis Nicolas LaLaurie, who was much younger than she,[10] on June 25, 1825.[9] In 1831, she bought property at 1140 Royal Street,[11] which she managed in her own name with little involvement of her husband,[10] and in 1832 had built a 2-story mansion there,[9] complete with attached slave quarters. She lived there with her third husband and two of her daughters,[10] and maintained a central position in New Orleans society.[2]

Torture and murder of slaves and 1834 LaLaurie mansion fire

The LaLaurie maintained several black slaves in slave quarters, attached to the Royal Street mansion. Accounts of Delphine LaLaurie's treatment of her slaves between 1831 and 1834 are mixed. Harriet Martineau, writing in 1838 and recounting tales told to her by New Orleans residents during her 1836 visit, claimed LaLaurie's slaves were observed to be "singularly haggard and wretched;" however, in public appearances LaLaurie was seen to be generally polite to black people and solicitous of her slaves' health,[10] and court records of the time showed that LaLaurie manumitted two of her own slaves (Jean Louis in 1819 and Devince in 1832).[12] Nevertheless, Martineau reported that public rumors about LaLaurie's mistreatment of her slaves were sufficiently widespread that a local lawyer was dispatched to Royal Street to remind LaLaurie of the laws relevant to the upkeep of slaves. During this visit, the lawyer found no evidence of wrongdoing or mistreatment of slaves by LaLaurie.[13]

Martineau also recounted other tales of LaLaurie's cruelty that were current among New Orleans residents in about 1836. She claimed that, subsequent to the visit of the local lawyer, one of LaLaurie's neighbors saw one of the LaLaurie's slaves, a twelve-year-old girl named Lia (or Leah), fall to her death from the roof of the Royal Street mansion while trying to avoid punishment from a whip-wielding Delphine LaLaurie. Lia had been brushing Delphine's hair when she hit a snag, causing Delphine to grab a whip and chase her. The body was subsequently buried on the mansion grounds. According to Martineau, this incident led to an investigation of the LaLauries, in which they were found guilty of illegal cruelty and forced to forfeit nine slaves. These nine slaves were then bought back by the LaLauries through the intermediary of one of their relatives, and returned to the Royal Street residences.[14] Similarly, Martineau reported stories that LaLaurie kept her cook chained to the kitchen stove, and beat her daughters when they attempted to feed the slaves.[15]

On April 10, 1834, a fire broke out in the LaLaurie residence on Royal Street, starting in the kitchen. When the police and fire marshals got there, they found a seventy-year-old woman, the cook, chained to the stove by her ankle. She later confessed to them that she had set the fire as a suicide attempt for fear of her punishment, being taken to the uppermost room, because she said that anyone who was taken there never came back. As reported in the New Orleans Bee of April 11, 1834, bystanders responding to the fire attempted to enter the slave quarters to ensure that everyone had been evacuated. Upon being refused the keys by the LaLauries, the bystanders broke down the doors to the slave quarters and found "seven slaves, more or less horribly mutilated ... suspended by the neck, with their limbs apparently stretched and torn from one extremity to the other", who claimed to have been imprisoned there for some months.[16]

One of those who entered the premises was Judge Jean-Francois Canonge, who subsequently deposed to having found in the LaLaurie mansion, among others, a "negress ... wearing an iron collar" and "an old negro woman who had received a very deep wound on her head [who was] too weak to be able to walk." Canonge claimed, that when he questioned Madame LaLaurie's husband about the slaves, he was told in an insolent manner that "some people had better stay at home rather than come to others' houses to dictate laws and meddle with other people's business."[17]

A version of this story circulating in 1836, recounted by Martineau, added that the slaves were emaciated, showed signs of being flayed with a whip, were bound in restrictive postures, and wore spiked iron collars which kept their heads in static positions.[15]

When the discovery of the tortured slaves became widely known, a mob of local citizens attacked the LaLaurie residence and "demolished and destroyed everything upon which they could lay their hands".[16] A sheriff and his officers were called upon to disperse the crowd, but by the time the mob left, the Royal Street property had sustained major damage, with "scarcely any thing [remaining] but the walls."[18] The tortured slaves were taken to a local jail, where they were available for public viewing. The New Orleans Bee reported that by April 12 up to 4,000 people had attended to view the tortured slaves "to convince themselves of their sufferings."[18]

The Pittsfield Sun, citing the New Orleans Advertiser and writing several weeks after the evacuation of LaLaurie's slave quarters, claimed that two of the slaves found in the LaLaurie mansion had died since their rescue, and added, "We understand ... that in digging the yard, bodies have been disinterred, and the condemned well [in the grounds of the mansion] having been uncovered, others, particularly that of a child, were found."[19] These claims were repeated by Martineau in her 1838 book Retrospect of Western Travel, where she placed the number of unearthed bodies at two, including the child.[15]

Escape from justice and self-imposed exile in France

Delphine LaLaurie's life after the 1834 fire is not well documented. Martineau wrote in 1838, that LaLaurie fled New Orleans during the mob violence that followed the fire, taking a coach to the waterfront and travelling, by schooner, from there to Mobile, Alabama and then on to Paris.[20] Certainly by the time Martineau personally visited the Royal Street mansion in 1836 it was still unoccupied and badly damaged, with "gaping windows and empty walls".[21]

Later life and death

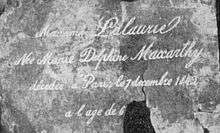

The circumstances of her death are also unclear. George Washington Cable recounted in 1888, a then-popular but unsubstantiated story, that LaLaurie had died in France, in a boar-hunting accident.[22] Whatever the truth, in the late 1930s, Eugene Backes, who served as sexton to St. Louis Cemetery #1 until 1924, discovered an old cracked, copper plate in Alley 4 of the cemetery. The inscription on the plate read "Madame LaLaurie, née Marie Delphine Maccarthy, décédée à Paris, le 7 Décembre, 1842, à l'âge de 6--."[23]

According to the French archives of Paris, however, Marie Delphine Maccarthy died on December 7, 1849.[1]

LaLaurie mansion

The New Orleans house occupied by Delphine LaLaurie at the time of the 1834 fires stands today at 1140 Royal Street, on the corner of Royal Street and Governor Nicholls Street (formerly known as Hospital Street). At three stories high, it was described in 1928 as "the highest building for squares around", with the result that "from the cupola on the roof one may look out over the Vieux Carré and see the Mississippi in its crescent before Jackson Square".[24] The entrance to the building bears iron grillwork, and the door is carved with an image of "Phoebus in his chariot, and with wreaths of flowers and depending garlands in bas-relief".[24] Inside, the vestibule is floored in black and white marble, and a curved mahogany-railed staircase runs the full three stories of the building. The second floor holds three large drawing rooms connected by ornamented sliding doors, whose walls are decorated with plaster rosettes, carved woodwork, black marble mantle pieces and fluted pilasters.[24]

Subsequent to LaLaurie's departure from America, the house remained ruined at least until 1836,[21] but at some point prior to 1888 it was "unrecognizably restored",[25] and over the following decades was used as a public high school, a conservatory of music, a tenement, a refuge for young delinquents, a bar, a furniture store, and a luxury apartment building.[26]

In April 2007, Nicolas Cage bought the LaLaurie House through Hancock Park Real Estate Company, LLC, for a sum of $3.45 million.[26] The mortgage documents were arranged in such a way that Cage's name did not appear on them.[27] On November 13, 2009, the property, then valued at $3.5 million, was listed for auction as a result of bank foreclosure and purchased by Regions Financial Corporation for $2.3 million.[27]

LaLaurie in folklore

Folk histories of Lalaurie's poor treatment of her slaves circulated in Louisiana during the nineteenth century, and were reprinted in collections of stories by Henry Castellanos[28] and George Washington Cable.[29] Cable's account (not to be confused with his unrelated 1881 novel Madame Delphine) was based on contemporary stories in newspapers such as the New Orleans Bee and the Advertiser, and upon Martineau's 1838 account, Retrospect of Western Travel, but mixed in some synthesis, dialogue and supposition entirely of his own creation.[29]

After 1945, stories of the Lalaurie slaves became considerably more explicit. Jeanne deLavigne, writing in Ghost Stories of Old New Orleans (1946), alleged that Lalaurie had a "sadistic appetite [that] seemed never appeased until she had inflicted on one or more of her black servitors some hideous form of torture" and claimed that those who responded to the 1834 fire had found "male slaves, stark naked, chained to the wall, their eyes gouged out, their fingernails pulled off by the roots; others had their joints skinned and festering, great holes in their buttocks where the flesh had been sliced away, their ears hanging by shreds, their lips sewn together ... Intestines were pulled out and knotted around naked waists. There were holes in skulls, where a rough stick had been inserted to stir the brains."[30] DeLavigne did not directly cite any sources for these claims, and they were not supported by the primary sources.

The story was further popularized and embellished in Journey Into Darkness: Ghosts and Vampires of New Orleans (1998) by Kalila Katherina Smith, the operator of a New Orleans ghost tour business. Smith's book added several more explicit details to the discoveries allegedly made by rescuers during the 1834 fire, including a "victim [who] obviously had her arms amputated and her skin peeled off in a circular pattern, making her look like a human caterpillar," and another who had had her limbs broken and reset "at odd angles so she resembled a human crab".[31] Many of the new details in Smith's book were unsourced, while others were not supported by the sources given.

Today, modern re-tellings of the Lalaurie legend often use deLavigne and Smith's versions of the tale to found claims of explicit tortures, and to place the number of slaves who died under Lalaurie's care at as many as one hundred.[32]

In popular culture

- The former, now defunct, historically themed wax museum in the French Quarter, the Musée Conti Wax Museum, on Conti Street, traditionally included a scene depicting abused slaves in Madame LaLaurie's attic.

- Poet Jennifer Reeser has written a poem in terza rima titled "The Lalaurie Horror," chronicling the mansion's history and folklore, done as a poetic "ghost tour."[33]

- In 2000, Ted Nicolaou directed a found footage movie called The St. Francisville Experiment about people who spend the night in a disused Louisiana plantation house and encounter hostile ghosts. While not the LaLaurie house in New Orleans, the plantation house is one location LaLaurie is alleged to have fled to after the 1834 fire incident. The fictional camera crew finds physical and supernatural evidence suggesting that LaLaurie did indeed flee to the house and continue her cruelty there.[34][35]

- In 2004, James Merendino directed "Trespassing," aka "Evil Remains," about a grad student of folklore leading his friends on a research expedition to an old plantation estate near New Orleans. The site, once the home of a woman whose backstory is directly taken from the bio of LaLaurie, is reputed to mysteriously cause madness and death to all who enter it.

- Kathy Bates portrays a heavily fictionalized Delphine LaLaurie in the 2013 third season of the American anthology horror television series American Horror Story.[36]

- Delphine LaLaurie is depicted as a reincarnation of the demoness Lilith in the 2015 Martin Kage book, Demoness.

- Delphine LaLaurie is a character in the board game Evil Baby Orphanage.

- Delphine LaLaurie appears as a character in Deadtime Stories, a PC game, (Deadtime Stories; developed by I-play and distributed by Big Fish Games), as a voodoo queen named Jessie Bodeen tells you her story of her commission by Delphine LaLaurie to drive away another socialite who was new in town and already more popular than Delphine Lalaurie, only for Delphine LaLaurie to renege on the deal when Jessie Bodeen had kept up her end of it. Jessie Bodeen seeks revenge on Delphine LaLaurie by invoking the Loa (who punish Delphine LaLaurie, and then Jessie Bodeen, 10 years later, for having taken on Delphine LaLaurie's commission).

- Delphine LaLaurie appears in the second of Barbara Hambly's Benjamin January mysteries, Fever Season.

- The story of the LaLaurie house is told and fictionally expanded on in issues 13-18 of Serena Valentino's Nightmares & Fairy Tales.

- Delphine LaLaurie's story serves as a basis for John Dickson Carr's Mystery Story "Papa La Bas" (first published in 1968). Unusually, it casts doubts on the truth of the torturing of slaves by LaLaurie.

- Delphine LaLaurie is the stage name of Glaswegian musician, Andrew Bell, who released an EP named nightmares and fairly tales.

See also

- Elizabeth Báthory

- Elizabeth Branch

- Elizabeth Brownrigg

- John Crenshaw

- History of slavery in Louisiana

- Augustin de Macarty

- La Quintrala

- Darya Nikolayevna Saltykova

Notes

- 1 2 Paris Archives online; scroll over to page 26, retrieved 31 October 2015.

- 1 2 "A torture chamber is uncovered by arson - Apr 10, 1834 - HISTORY.com". Retrieved on 23 January 2017.

- 1 2 King (1921), pp. 368–373.

- ↑ Archdiocese of New Orleans Sacramental Records Volume 01 (1718-1750), p. 167.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Arthur (1936), p. 148.

- ↑ King (1921), p. 373.

- ↑ King (1921), p. 359.

- 1 2 King (1921), pp. 359–360.

- 1 2 3 Arthur (1936), p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 Martineau (1838), p. 137.

- ↑ Cable (1888), p. 200.

- ↑ Orleans Parish Court, Index to Slave Emancipation Petititions, 1814–1843, City Archives and Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library.

- ↑ Martineau (1838), p. 138.

- ↑ Martineau (1838), pp. 138–139.

- 1 2 3 Martineau (1838), pp. 139.

- 1 2 New Orleans Bee (April 11, 1834).

- ↑ As quoted by Castellanos (1895), pp. 58–59.

- 1 2 The New Orleans Bee (April 12, 1834).

- ↑ Pittsfield Sun (May 8, 1834).

- ↑ Martineau (1838), pp. 141–142.

- 1 2 Martineau (1838), p. 142.

- ↑ Cable (1888), p. 217.

- ↑ Times-Picayune (January 28, 1941).

- 1 2 3 Saxon (1928), p. 203.

- ↑ Cable (1888), p. 192.

- 1 2 Big Time Listings (April 24, 2007).

- 1 2 CNN Money (November 16, 2009).

- ↑ Castellanos (1895), pp. 52–62.

- 1 2 Cable (1888), pp. 200–219.

- ↑ DeLavigne (1946), pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 19.

- ↑ Taylor (2000).

- ↑ http://www.amazon.com/The-Lalaurie-Horror-Jennifer-Reeser/dp/061587262X/ref=tmm_pap_title_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1380282793&sr=8-1

- ↑ "The St. Francisville Experiment". 3 October 2001. Retrieved on 23 January 2017 – via IMDb.

- ↑ "The St. Francisville Experiment". Retrieved on 23 January 2017.

- ↑ "FX's John Landgraf on 'American Horror Story: Coven:' 'It's really funny this year'". Retrieved on 23 January 2017.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LaLaurie House, New Orleans. |

Books

- Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1936). Old New Orleans: A History of the Vieux Carré, Its Ancient and Historical Buildings. New Orleans, LA: Harmanson. ISBN 0788427229. OCLC 19380621.

- Cable, George Washington (1888). Strange True Stories of Louisiana. New York: The Century Co. ISBN 0-559-09492-2.

- Castellanos, Henry C; Kelleher Schafer, Judith; Reinecke, George F (1895). New Orleans as it was: episodes of Louisiana life. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-3209-8.

- Cosner Love, Victoria; Shannon, Lorelei (2011). Mad Madame Lalaurie. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1609491994.

- de Bachellé Seebold, Herman Boehm (1941). Old Louisiana Plantation Homes and Family Trees. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing. ISBN 1-58980-263-2.

- DeLavigne, Jeanne (1946). Ghost Stories of Old New Orleans. New York; Toronto: Rinehart & Co. OCLC 5128595.

- Heinan, Timothy (2012). L'immortalité: Madame Lalaurie and the Voodoo Queen. Bellevue,WA: On Demand Publishing, LLC-Create Space. ISBN 978-0615634715.

- King, Grace Elizabeth (1921). Creole Families of New Orleans. New York: MacMillan & Co. ISBN 0-87511-142-4. OL 13489529M.

- Martineau, Harriet (1838). Retrospect of Western Travel. 2. London: Saunders & Otley. OCLC 80223671.

- Morrow Long, Carolyn (2012). Madame Lalaurie Mistress of the Haunted House. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813038063.

- Saxon, Lyle (1928). Fabulous New Orleans. New York, London: The Century Co. ISBN 9781455604029. OCLC 421892.

- Smith, Kalila Katherina (1998). Haunted History Tours presents... Journey Into Darkness: Ghosts & Vampires of New Orleans. New Orleans, LA: De Simonin Publications. ISBN 1-883100-04-6.

Academic papers

- Morlas, Katy Francis (2005). La Madame Et La Mademoiselle: Creole Women In Louisiana, 1718–1865 (PDF) (Master of Arts thesis). Louisiana State University.

- Baker, Courtney R (2008). Misrecognized: Looking at Images of Black Suffering and Death (PhD thesis). Duke University.

Periodicals

- "The conflagration at the house occupied by the woman Lalaurie.." (PDF). New Orleans Bee. April 11, 1834. – The relevant text appears at the top-left of the linked scan. A transcript of this article can be found here for ease of reading.

- "The popular fury which we briefly adverted to in our paper of yesterday.." (PDF). New Orleans Bee. April 12, 1834. – The relevant text appears at the top-left of the linked scan. A transcript of this article can be found here for ease of reading.

- Pittsfield Sun. May 8, 1834. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Epitaph-Plate of 'Haunted' House Owner Found Here". The Times-Picayune. January 28, 1941. – A transcript of this article can be found here for ease of reading.

- "History of Delphine Macarty Lalaurie and the Haunted House on Royal Street" updated on 27 Sept 2013 at The Times-Picayune's NOLA.com; retrieved 31 Oct 2015.

Web content

- Goldsborough, Bob (April 24, 2007). "Nicolas Cage buys house in New Orleans' French quarter for $3,450,000". Big Time Listings. Celebrity Real Estate Homes Big Time Listings. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- Taylor, Troy (2000). "The Legacy of Madame Delphine LaLaurie". Denise's Dreams. Strange Nation. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- Yousuf, Hibah (November 16, 2009). "Nicolas Cage loses 2 homes in foreclosure auction". CNNMoney.com. Cable News Network. Retrieved December 30, 2010.