Marie Daulne

| Marie Daulne | |

|---|---|

Marie Daulne singing in Baltimore, US on November 2007 | |

| Born |

20 October 1964 Isiro, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Occupation | singer |

Marie Daulne /ˈduːlɪn/[1][2] (born 20 October 1964) is a Belgian singer.

Daulne was born in Isiro, Haut-Uele District, Democratic Republic of the Congo to a Belgian who was killed that same year by Simba rebels, and to a local Congolese woman. Daulne and her mother and sisters were airlifted out to Kinshasa in an emergency evacuation by Belgian paratroopers[3] and flown to Belgium because their father had been a Belgian citizen.[4] Daulne was raised in Belgium and as of 2007 calls Brussels home, but lived in New York City for three years starting in 2000.

Daulne is the founder and lead singer of the music group Zap Mama whose second album, Adventures in Afropea 1, "became 1993's best-selling world music album and established Zap Mama as an international concert sensation." With "over six albums and countless concerts, she continues to pay tribute to the family's saviors." Daulne insists that "one tune on each of her reggae-, soul-, funk- and hip-hop-infused albums be a traditional Pygmy song."[3]

Daulne says her mission is to be a bridge between the European and the African and bring the two cultures together with her music.[4] "What I would like to do is bring sounds from [Africa] and bring it to the Western world, because I know that through sound and through beats, that people discover a new culture, a new people, a new world."[5] Daulne specializes in polyphonic, harmonic music with a mixture of heavily infused African instruments, R&B, and Hip-hop and emphasizes voice in all her music.[4] "The voice is an instrument itself," says Daulne.[4] "It's the original instrument. The primary instrument. The most soulful instrument, the human voice."[6] Daulne calls her music afro-European.

Early life and musical origins

Daulne was born in Isiro, (pronunciation: "ee SEE roh" or [IPA] /i 'si ro/) Haut-Uele District, one of the largest cities in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[7] as the fourth child of a white civil servant,[3] Cyrille Daulne, a Walloon (French-speaking Belgian) and Bernadette Aningi, a woman from Kisangani, formerly Stanleyville, the third largest city in Congo Kinshasa.[4]

When Daulne was only a week old, her father was attacked and killed by Simba rebels, who were opposed to mixed-race relationships.[4] "He did not have a chance to come with us because he was captured," Daulne says.[8] "He said to my mother, 'Escape,' and we escaped into the forest, and the Pygmies hide us while we were waiting to see what happens," says Daulne.[3] "He was a prisoner of the rebels for a while, then they killed him."[8] Her mother was arrested by the rebels but was later set free because she spoke their language.[4] Daulne pays tribute to those pygmies who rescued her family in the song "Gati" from Supermoon.[9] "They saved my family and many others during the Congolese rebellion," Daulne says, "and they deserve recognition for that."[9] "My promise to them was I used your song to be known in the world and my goal is to talk about you," Daulne added.[3]

After eight months in the interior of the country,[1] Daulne and her mother,brother and sisters were eventually airlifted out to Isiro in an emergency evacuation by Belgian paratroopers[3] and flown to Belgium because their father had been a Belgian citizen.[4] "I think the experience of the political situation is more my mother, who had to survive. I was a baby, and I just was protected by my mother. What I know that I learned from my mother is to be strong and to stay positive in any kind of situation; that's the best weapon to survive. That's what I learned, and this is the main message I pass into my music," says Daulne.[5] Everything was different when Daulne, her mother, five other sisters, and an aunt arrived in Belgium.[10][11] "When we arrived, it was snowing, and my mother said, 'Look — the country of white people is white!'" says Daulne.[10]

Growing up in Belgium was hard for Daulne.[12] "It was hard as a kid, you want to look like everybody else, and there aren’t many black people in Belgium – compared to England, or America or France," says Daulne.[12] "It became easier as I grew older. There were more black role models about – musicians and sports stars. At school I started to see my mixed heritage as a bonus – I could be part of both the African and Belgian communities."[12]

Interest in European music

Daulne listened to European music as she grew up.[13] "We had the radio when I was growing up in Belgium, so we heard a lot of French music. And of course, American music was also very popular all over Europe. Since our mother did not want us to watch TV in our home, we entertained ourselves by creating our own music. We were very musical."[14] Daulne was introduced to black music watching television.[13] "When I was growing up, there weren't many black people in Europe -- my family was alone. Then I saw an American musical comedy with black people on TV. And I couldn't believe it. I said, "That's us!" My whole fantasy life was based on that movie."[13] Daulne felt a special connection to blue songs like Damn your eyes by Etta James.[15] "When I was a teenager I listened to a lot of American blues," says Daulne.[15] "That song brought me happiness while I was going through the pain of a broken love. It helped me to open the door and see the life in front of me." Daulne said she sang that song as a teenager "alone in my room."[10] "It’s a magic song, it transforms — when I sang that song I cried, and you need to cry to heal."[10] "I sing it now and I hope, in my turn, that I can help another teenager to do the same if they are having pain from love."[15]

When Daulne was 14 she went to England and first heard reggae.[13] "I discovered Bob Marley -- my favorite album was Kaya. I know that whole album by heart."[13] Then Daulne became interested in the rap music of Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys.[13] "I was into breakdancing at the time. I formed a gang, and we would beatbox like the Americans, like the Fat Boys."[13]

Interest in African music

"When I was growing up, I refused all this tradition," Daulne says.[3] "It was boring . . . because it was not what we talked about at school, the bands of the moment. Nobody was talking about Pygmies and sounds from Africa. It was a little bit of shame to talk about the African roots."[3] But although Daulne was encouraged to adopt the language and culture of Belgium, her mother kept Congolese music alive in the household.[1] "In Africa, before you eat or do something, you sing to call the spirits of the peace, and my mother teach me that," Daulne says.[1] "I discover that, with my two cultures, I have something very rich in me."[1]

Although Daulne remembers that her mother sang some songs from Congo Kinshasa around the house, her mother did not teach them to the children, stressing mastery of French instead[7] but after Daulne left home she remembered the African songs her mother sang to her as a child.[16] "Our mother would make us learn the polyphonic singing, but at the time we thought it was boring because it was traditional," says Daulne.[17] When Daulne went away to school, here sister and Daulne started to sing African melodies.[3][16] "When I left home, I missed those songs, and in the school choir, I wondered why we didn't use African harmonising. So my sister and I started to sing African melodies, and Zap Mama was born. I wrote my first song at 15, and my artist friend Nina said that what we were doing was amazing. She helped me to find a gig, and from that day, it has been non-stop."[16]

But Daulne didn't really get interested in singing until an accident she sustained while dancing in a stage show[18] left her unable to participate in athletics.[13] "I wanted to be a runner, but then I broke my leg and I was finished with sports. I stayed at home, listening to music. I was recording sounds all the time -- I would listen to sounds repeating for hours. But there was something that I needed still, and that's when I decided to go to Africa, to the forest."[13]

Return to Africa

In the documentary film Mizike Mama, Daulne and her family recall a reverse cultural tug-of-war for her allegiance during her childhood.[19] Her mother feared that Daulne would grow up too African and so did not teach her traditional songs.[19] Daulne first heard a recording of traditional pygmy music when she was 20.[20] "At 20, something happened in me," Daulne says.[3] "When you pass 13, 14, you want to look like the others, but after a certain point you want to be unique. And those sounds did something to me."[3]

Daulne studied jazz in college but decided that she wanted to focus on a different kind of sound that blended musical traditions from around the globe.[11] The Antwerp School of Jazz provided Daulne a brief period of formal training where she studied "Arab, Asian and African polyphony."[11] Then Daulne decided to return to Congo Kinshasa in 1984[7] to learn about her heritage and train in pygmy onomatopoeic vocal techniques.[20] "When I went to the Congo, I hadn’t thought of being a musician. Not at all. But I was there, and I was standing in the middle of the forest, hearing the music that had been a part of my earliest memories, and it was like an illumination, like a light," Daulne said.[14]

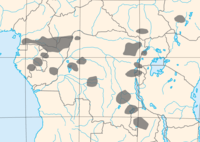

Daulne made further trips to Africa.[7] "I go all around Africa. I started where I was born, in the forest of Zaire. After that I branched out to West Africa, South Africa, East Africa. It [is] very easy for me to learn because all African cultures seem to have something in common the music and the voices," Daulne says.[7]

Although Daulne draws inspiration from Africa, she does not call Africa home.[8] "You know when I went back to Congo, I thought I would have a welcome like I was part of the family, part of the country, but that was not the case," Daulne said.[8] "They treated me like a Belgian come to visit as a tourist. I saw that that is not especially a place to call home."[8] But Daulne is proud of the success of her music in Congo Kinshasa and says it helps restore a sense of pride and history to Africans and Westerners of African descent.[11] "In Africa they want to change, to become like white people, but I tell them, 'Stay like you are,'" says Daulne.[11] "In the beginning my mother didn't understand why I always asked her about traditional music, because everybody wants to do American-style music. Colonization changed the mentality of our parents. After Zap Mama, my mother and my aunt began to sing together again, and now my aunt says, 'Thank you.'"[11]

African European music

Daulne's music is a hybrid of African and European influences.[21] "If people want to know where my sounds are from, I say I’m an African European," says Daulne.[22] "There is the African American, and then there is the African European like me. My background is from Africa, and I grew up in the urban world of Europe. And I would say Afro-urban is easy to understand because it is urban music, but at the same time you have African elements in it."[22] "I think it’s because I’m born of two cultures. From my African heritage, I receive a lot of different harmonies and sounds and ways to express melody and probably all of this makes up what I do," says Daulne.[21] "Some say it’s African music that I do, but definitely not. I’m not African at all. My harmony is from Europe. I use things from all over the place. I use all these sounds and people can hear it. It’s because we are all human-we all want the same things."[21]

Citizen of the world

Other influences in Daulne's music include Brazil where she visited in 2008.[23] "I fell in love. The weather, the music — I was like a child. It's amazing," Daulne says.[23] Daulne went to Brazil "to first discover the country. The beauty of the city, the people walking, and haircuts — just feel what it is to be a woman in Brazil. I did my braid over there with a woman from the favelas and I have a friend who speaks Portuguese who was able to translate and have conversations. Now my music will have a Brazilian touch on my next album, definitely."[23]

Daulne has traveled the world to seek cultural connections with people around the planet.[23] "Inside me, I feel like a citizen of the world," Daulne says.[23] "In New York, it was the case that I found a lot of people from all over the place and what we talk about is what the human being can exchange as a person. The main thing I want in songs is what the feeling of the human being is."[23]

Zap Mama

Daulne defines her music over the years as evolving from an a cappella quintet to instruments and a lead voice.[24] "I’m a nomad. I like to discover my sound with different instruments, different genres. For me it’s normal. My name is Zap Mama – it’s easy to understand that it’s easy for me to zap in from one instrument to another, a culture, a style. I’m more a citizen of the world, not an American or Belgian."[24] The word Zap also means to switch TV channels or in this context to switch cultures.[18] Zap Mama have released seven full-length albums: Zap Mama (1991), Adventures in Afropea 1 (1993), Sabsylma (1994), Seven (1997), A Ma Zone (1999), Ancestry in Progress (2004), and Supermoon (2007) that fall into three cycles.[14]

First Cycle: Adventures in Afropea 1 and Sabsylma

Daulne returned to Belgium ready to begin making her own music.[1] "Spending time with the pygmies, all the music came to me," Daulne says.[1] "And when I came back to Belgium, I found all the energy to put it all together, and to find singers to sing with me."[1] By 1989 Daulne had spent several years singing in Brussels in jazz cafes when she decided to create a group to merge the cultures of her life and in 1990 founded the group Zap Mama.[25] "I didn't want to use my own name, I didn't really feel like it would come from me, because it was like the spirit of the ancestors talking to me and using me to translate what's going on," Daulne says.[1]

Daulne couldn't work as a solo artist.[11] "I saw in Zaire that I have to mix with other people, because with me alone, the polyphony is not there," says Daulne.[11] "I knew there must be singers in the world I could mix with, and I found them."[11] Daulne auditioned scores of female singers looking for the right combination of voices for an a cappella ensemble.[26] "When I did my first album, I was looking for girls that were the same mix as me--African and European," she says.[15] "Because I wanted to put these two sounds together to prove that to have blood from white and black was perfect harmony on the inside."[15] "I remembered Sylvie Nawasadio because we used to sing together on the train going to school," says Daulne.[10] "I met her again at the university in Brussels, studying sociology and anthropology. I asked her if she wanted to be a part of a cultural singing group. And Sabine [Kabongo] is, like me, a mixture–Zairean and Belgian. After her, I held an audition, and discovered Marie Alfonso, who’s Portuguese and white. Then came Sally Nyolo and the first concert, in November 1989."[10] The original idea of Zap Mama was "five singers who would be one as the pygmy," Daulne said.[27] "There is no chief."[27] "The power of voices was my thing," Daule said.[26] "I wanted to show the world the capacity of five women exploring with our voices and our minds, nothing else."[26] Daulne felt she was channeling the spirit of her Congolese ancestry so instead of using her own name, she called the group Zap Mama.[26] "We have a Zairean memory and a European memory, and together we find the same vibration, because we have European and Zairean music inside," said Daulne.[11] Combining the sounds of Pygmies with vocal styles of European choral traditions.[25] Zap Mama received initial support from the French Belgian Community Government's cultural department but the group soon came to the attention of Teddy Hillaert when he saw them perform at the Ancienne Belgique in Brussels.[11] "It's a mixture of humor, dance, color; it's really powerful," Hillaert said.[11] "Their show sold out so quickly, I said 'This is amazing.'"[11] Hillaert became Zap Mama's manager and in Summer, 1991[11] the group began recording their first record Zap Mama at Studio Daylight in Brussels. Belgium[28] The album was completed in October, 1991[11] and released by Crammed, the Belgian record label of Marc Hollander and Vincent Kenis.[6] Hollander said that Zap Mama "present Western audiences with an impression of Africa which is half-real and half-imaginary. They research and reinterpret certain forms of traditional music, but from a semi-European standpoint, with a lot of humor, and a vision which doesn't lack social and political content."[11]

Zap Mama began picking up fans in the United States even before their arrival earning exposure at a college radio station at the University of Santa Monica, where the album topped the station's unofficial charts for several weeks.[11] In 1992 Marc Maes wrote in Billboard that Zap Mama was the "flavor of the month on the international circuit."[11] Randall Grass praised them in the Village Voice for their "positively ground-breaking amalgams of African, Arabic, and European melody, and snatches of South African mbube amidst a little Bulgarian mystere."[11] When Zap Mama came to the United States for the first time in 1992 to perform at New Music Seminar in New York they met David Byrne and agreed to let him reissue Zap Mama's first recordings as Adventures in Afropea 1[14] on Luaka Bop Records.[27] "I don't know the music of this man, but I know this man is good," said Daulne.[11] "We have the same passion."[11] Yale Evelev, President of Luaka Bop Records, said Zap Mama had made an impression on him and Byrne.[11] "It's very popular music but there's a real artistic underpinning to it. It's not someone saying, 'What can I do to be successful?' It's someone saying, 'This is the music I want to do.'"[11]

Luaka Bop Records repackaged the first Crammed Discs release for American listeners in 1993 as Adventures in Afropea 1.[11] By the end of the year, Billboard announced it was the top seller for "world music."[27] Zap Mama went on tour playing New York's Central Park, Paris' Olympia, the Jazz-festival of Montreux.[6] After the success of Adventures in Afropea 1, Daulne said the record company "wanted to mould us into a poppy girl band, but I said, 'No, you'll kill me', and I stopped. Everyone was asking why I wanted to stop when we'd finally arrived at the top. But I felt that it was completely wrong. I wasn't ready. I wasn't strong enough. The manager said that if I stopped then, I'd be killing my career, but it was my decision."[16]

The next album Sabsylma (1994) contained music with Indian, Moroccan and Australian influences[25] and earned Zap Mama a Grammy nomination for Best World Music Album.[14] Daulne explained that the sharper sound of Sabsylma was due to the increasing influence of American music and the sound of being on the road.[6] "We've been touring so intensively. Zap Mama was a soft, African record with a natural, round sound. Sabsylma is hectic, sharper. Not on purpose, mind you. I can't help it. If you're driving in a van for months, and you constantly hear the sounds of traffic, TV, hardrock on the radio ... those sounds hook up in your ears, and come out if you start to sing."[6] Daulne also broadened her music to embrace other cultures on Sabsylma.[10] "Before I spoke about the Pygmies and the people around them. Now I want to talk about the people around me," says Daulne.[10] "My neighbor who has nothing to eat–I want to know what’s going on inside his head. Some of the most rewarding travel I’ve done was just ringing my neighbors’ doors. My Moroccan neighbor shared her Moroccan world. The Pakistani man at the grocery showed me Pakistan. That’s what this album is about–I suggest that people dream and travel in their own cities by talking to their neighbors."[10]

Daulne used an organic process to improvise her music in the studio.[6] "I'm always looking for sounds. Most of the time, I work with colors. Each sound needs different colors of voices. I dissect sounds, cut them in little pieces, order them, and reassemble them," says Daulne.[6] "The songs themselves come about in a very organic, improvising way. During the rehearsals, we light some candles, start a tape-recorder, close our eyes, and start making up a story. On that, we start adding sounds. We let ourselves go. We are carried away by the music."[6]

At the same time Sabsylma was being created, Director Violaine de Villers made a documentary, Mizike Mama, (1993) that presents a group portrait of Zap Mama.[19] The film focuses on Daulne and discusses the implications of membership in a racially mixed group that consciously fuses African rhythms and vocal tones with European polyphony.[19] The documentary won the International Visual Music award for Best Popular Music TV Documentary.[10]

Second Cycle: Seven and A Ma Zone

After the success of the first two albums, Daulne put her music on hold for a few years to birth and mother her daughter Kesia. Adventures in Afropea 1 and Sabslyma had both been largely a cappella.[7] In 1996, Daulne decided to dissolve the group and make a formal break from a cappella, retaining the Zap Mama name but looking for new collaborators in the United States.[1] Daulne moved her music in a different direction[7] coming back as the lone Zap Mama to record Seven, a break with the past for the inclusion of male musicians and vocalists, the increased number of instruments and the number of songs in English.[7] "I made music on Seven the same way as on the other albums. I only used acoustic instruments... I'm looking for instruments that have vocal sounds, forgotten instruments like the guimbri... The first and second albums were about the voice, what came before. This album is about introducing those sounds into modern, Western life," says Daulne.[25] Daulne had help on the album from Wathanga Rema, from Cameroon.[10] "I couldn’t have made this album without him!" says Daulne.[10] "I met someone who could sing high female parts and also have that male power... that changed everything!"[10] Daulne's sister Anita also contributed to both songwriting and vocals.[10] "She always knows when I fly too high and when I lose my way," says Daulne.[10]

The title of Seven (1997)[14] refers to the seven senses of a human being.[25] Daule had traveled to Mali in 1996 and had learned from a man in Mali that in addition to the five senses known in the west, some have a sixth sense which is emotion.[25] "But not everyone has the seventh. It is the power to heal with music, calm with color, to soothe the sick soul with harmony. He told me that I have this gift, and I know what I have to do with it," Daulne says.[6]

Daulne's next album was A Ma Zone (1999).[14] The title is a wordplay meaning both "Amazone," the female warrior, and "A Ma Zone," (in my zone)[6] which "means that I feel at ease wherever I am," Daulne says.[14] "Naturally an Amazon is a rebel, a fighter who, once she has set her heart on something, pulls out all the stops to achieve her goal. I feel this way as well when I'm standing on the stage with the group.- as a team we share the same aim of winning over the audience with our music. I'm a nomad. I'm meeting new people all the time and sealing these friendships with tunes," Daulne says.[14]

Third Cycle: Ancestry in Progress and Supermoon

Daulne moved to New York in 2000.[27] "I've never been welcome in any country as my own country," says Daulne.[27] "In Europe, they talk to me as if I'm from Congo. In Congo, they act like I'm from Europe. The first time I felt at home was in New York. I said, ‘Here is my country. Everybody is from somewhere else. I feel so comfortable here.'"[27] Ancestry in Progress (2000) reflects Dualne's new life in the United States.[14] "The American beat is a revolution all over the world," Daulne says.[14] "Everybody listens to it and everybody follows it. But the beat of the United States was inspired by the beat coming from Africa. Not just its structure, but the sound of it. This is the source of modern sounds, the history of the beat, starting from little pieces of wood banging against one another, and arriving on the big sound-systems today. It's genius. So I wanted to create an album about the evolution of old ancestral vocal sounds, how they traveled from Africa, mixing with European and Asian sounds, and were brought to America."[14]

Daulne collaborated with the Roots collective in Philadelphia who acted as producers for Ancestry in Progress.[1] "They invited me to do some of my sounds in one of their albums, and that was where the relationship develop[ed]," says Daulne.[21] "The hardest [thing was] that at the time my English was so little that I had no way to express myself, so I didn’t know how it happened in the Philly world or the United States, or the way it work[ed] with studios. I was there, like in the middle of an ocean with my sounds, my spirit and my vibe."[21] "What I like about the Roots is their instruments, the jazz background, which is helping to have a real, acoustic, organic sound," says Daulne.[1] "If you take it and make it groovy, it seems like our life is lighter and easier. ... And I loved the beatbox which some of their members were doing, grooving with only [their] mouth."[1] One of the tracks includes baby sounds from Daulne's youngest child, Zekey.[1] Ancestry in Progress (2004),[14] reached #1 on the Billboard World Music Album chart.[29]

Daulne moved back to Belgium after three years in the United States[30] and now calls Brussels home.[12] "I lived in the United States from 2000 to 2004 and it is a place with so many stars. When I met a lot of big celebrities I realized I was not a big star and that I didn't want to be, because your life would be a habit, stuck in this and that. I prefer the singularity. I prefer to be me."[26] Daulne finds life easier in Belgium.[12] "I used to live in New York, and the system in Belgium is much better than in America. It’s much easier for families here."[12] "With my family, my husband, my children, the people I love — that is home."[8] Daulne still draws inspiration from her travels.[30] "Currently, I feel the need to go to England, because a lot of interesting things are happening over there. In my band, there are a lot of young musicians who teach me completely new things. They challenge me - and that is the way I like it," Daulne says.[30] Daulne also found American interests and values different from Europe.[23] "American people are so addicted to music — sports and music," says Daulne.[23] "Where I live, with the French influence, it's the foods that are very important, and literature — all this probably more important than sports and music."[23]

In Supermoon (2007),[14] Daulne's vocals take centerstage.[27] "When the audience appreciates the art of the artist, the audience becomes the sun and makes the artist shine as a full moon," says Daulne.[27] Supermoon is also one of Daulne's most personal statements[29] with songs like "Princess Kesia," an ode to her daughter and how she is no longer a baby but a beautiful girl.[31] "With Supermoon, I reveal the way I chose to live when I started my career,” says Daulne.[29] “It’s very intimate…You’re seeing me very close up. I hope that’s a kind of intimacy that people will understand. I’m opening a door to who I am."[29] "I always used to hide myself, and I'm not complaining about it, but now it is time to show my eyes and my femininity and my delicate side," said Daulne.[26] "I am proud to be so feminine, because I have taken the time to develop the inside of my femininity. Now that I have that, I can face anybody. And if anybody challenges me, there is no problem."[26]

Discography

- Zap Mama (1991)

- Adventures in Afropea 1 (1993)[14]

- Sabsylma (1994)[14]

- Seven (1997)[14]

- A Ma Zone (1999)[14]

- Ancestry in Progress (2004)[14]

- Supermoon (2007)[14]

- ReCreation (2009)

Collaboration with other artists

- Daulne is a guest performer on the song "Listener Supported" by Michael Franti, from the album Stay Human.[32]

- Daulne is featured on the track "Ferris Wheel" from Common's 2002 album Electric Circus.[33]

- Daulne is featured on the soundtrack to La Haine, a French film which she recorded with her brother Jean-Louis Daulne.[34]

- Daulne is a guest performer on the song "Comin' to Gitcha" by Michael Franti, from the album Chocolate Supa Highway.[17]

- Daulne is featured on the song "Danger of Love" by DJ Krush, from the album Zen.[35]

Humanitarianism and activism

An active humanitarian, Daulne devotes much of her time working to protect human rights and fight global poverty with organizations such as Amnesty International, Doctors Without Borders, CARE, and the United Nations.[14] In 1993 Zap Mama was asked to sing a commercial for Coca-Cola and Daulne's initial response was no. However Daulne had second thoughts.[11] "But we do like Robin Hood," Daulne said.[11] "I thought there is money there that can go to help people. I see poor people and think, 'Maybe one day when Zap Mama is over, I can help people.' Then I thought, I can help people now."[11] Zap Mama made the commercial and used the money to help build a school in Africa.[18]

"I am here to fight for peace," says Daulne.[7] "I grew up in a country where there were mostly white people and they always pointed out that I was different, that I was black. We shouldn't ignore the problems. But always shouting, 'There is a problem! There is a problem!' will not help us to arrive at a solution. I think about what I can do to bring an end to it, then I face the problem and attack it one step at a time."[7] Daulne says that her music speaks for "the world that nobody wants to talk about - the disabled people. And people like us, we’re all looking for the best, we all have the same energies and mindset, and to remind us that it is not only our country and what TV tells us…we need to travel and open our mind and not follow especially the system, the manipulation of the politics that bring us fear. If we know what’s going on in this world, we see by our eyes and still with our bodies we can start to think about ourselves. This is what I want to see."[22]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Creative Loafing. "Zap Mama's Marie Daulne merges African, African-American sounds" by Jeff Kaliss. 5 April 2005

- ↑ IMDB. "Marie Daulne"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Washington Post "A Shimmering 'Supermoon'" by Richard Harrington. 2 November 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Intermix. "Marie Daulne Is Zap Mama."

- 1 2 Metroactive. "Zap Happy" by Mike Conner. 30 July 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 The Belgium Pop and Rock Archives. "Zap Mama."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rootsworld. "Marie Daulne talks with Jen Watson about unifying people through music"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 North Coast Journal. "The Way Home" by Bob Boran. 30 August 2007. Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Pitchfork Media. "Zap Mama Supermoon" by Roque Strew. 13 September 2007 Archived 31 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Luaka Bop. "A Brief History of Zap Mama" 1995. Archived 6 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Musician Guide. "Zap Mama Lyrics and Biography" by Ondine E. Le Blanc and James M. Manheim.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 there! the Inflight Magazine of Brussels Airlines. "Q & A with Marie Daulne" 1 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Barnes and Noble. "Urban Beats and Forest Chants Harmonize in Zap Mama's A MA ZONE." Archived 14 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Zap Mama. "Zap My Message = Zap Mama Welcome Page + Zap Marie = Zap Mama Bio." Archived 24 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Denver Westword. "Mama Knows Best" by Linda Gruno. 21 August 1997.

- 1 2 3 4 The Independent. "World Music: The second coming of Zap Mama" by Phil Meadley. 8 October 2004.

- 1 2 MCA Records. "Zap Mama" by Luaka Bop. 29 May 2002

- 1 2 3 Ballet Met. "World premiere of Suite Mizike" by Gerard Charles. October, 1996. Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 New York Times. "Djembefola." 15 September 1993.

- 1 2 Answers.com "Zap Mama."

- 1 2 3 4 5 A Coat of Red Paint in Hell. "Zap Mama: An Interview with Marie Daulne" by Shanejr. 28 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 Wingcom "Zap Mama’s Marie Daulne spawns musical revolution in Atlanta’s Variety Playhouse" by Tomi and Kurk Johnson. 20 April 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Read Express from the Washington Post. "Citizen of the World: Zap Mama" by Katherine Silkaitis. 30 June 2008. Archived 14 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 The Providence Journal. "Zap Mama: Citizen of the world" by Rick Massimo. 9 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Singers.com "Zap Mama."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Minneapolis Star Tribune. "Ready for her close-up" by Britt Robson. 18 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 San Diego City beat. "Superswoon: Zap Mama has to be seen to be believed in" by Troy Johnson 15 August 2007.

- ↑ CD Universe. "Adventures in Afropea 1."

- 1 2 3 4 Concord Music Group. "About Zap Mama."

- 1 2 3 Primary News: "New Signing - Zap Mama." September, 2004.

- ↑ Black Grooves. "Supermoon" 12 October 2007

- ↑ Six Degrees. "Michael Franti & Spearhead." Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Blue Beat. "Common -- Electric Circus (Clean)"

- ↑ Amazon. "La Haine (Hate)"

- ↑ Bush, John: Zen. DJ Krush. Review. allmusic