Man'yōshū

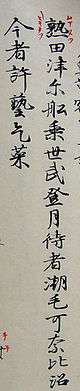

The Man'yōshū (万葉集, literally "Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves", but see Name below) is the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, compiled sometime after 759 AD during the Nara period. The anthology is one of the most revered of Japan's poetic compilations. The compiler, or the last in a series of compilers, is today widely believed to be Ōtomo no Yakamochi, although numerous other theories have been proposed. The last datable poem in the collection is from AD 759 (#4516[1]). It contains many poems from much earlier, many of them anonymous or misattributed (usually to well-known poets), but the bulk of the collection represents the period between AD 600 and 759. The precise significance of the title is not known with certainty.

The collection is divided into twenty parts or books; this number was followed in most later collections. The collection contains 265 chōka (long poems), 4,207 tanka (short poems), one tan-renga (short connecting poem), one bussokusekika (poems on the Buddha's footprints at Yakushi-ji in Nara), four kanshi (Chinese poems), and 22 Chinese prose passages. Unlike later collections, such as the Kokin Wakashū, there is no preface.

The Man'yōshū is widely regarded as being a particularly unique Japanese work. This does not mean that the poems and passages of the collection differed starkly from the scholarly standard (in Yakamochi's time) of Chinese literature and poetics. Certainly many entries of the Man'yōshū have a continental tone, earlier poems having Confucian or Taoist themes and later poems reflecting on Buddhist teachings. Yet, the Man'yōshū is singular, even in comparison with later works, in choosing primarily Ancient Japanese themes, extolling Shintō virtues of forthrightness (真 makoto) and virility (masuraoburi). In addition, the language of many entries of the Man'yōshū exerts a powerful sentimental appeal to readers:

[T]his early collection has something of the freshness of dawn. [...] There are irregularities not tolerated later, such as hypometric lines; there are evocative place names and makurakotoba; and there are evocative exclamations such as kamo, whose appeal is genuine even if incommunicable. In other words, the collection contains the appeal of an art at its pristine source with a romantic sense of venerable age and therefore of an ideal order since lost.[2]

Name

Although the name Man'yōshū literally means "Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves" or "Collection of Myriad Leaves", it has been interpreted variously by scholars.[3] Sengaku, Kamo no Mabuchi and Kada no Azumamaro considered the character 葉 yō to represent koto no ha (words), and so give the meaning of the title as "collection of countless words". Keichū and Kamochi Masazumi (鹿持雅澄) took the middle character to refer to an "era", thus giving "a collection to last ten thousand ages". The kanbun scholar Okada Masayuki (岡田正之) considered 葉 yō to be a metaphor comparing the massive collection of poems to the leaves on a tree. Another theory is that the name refers to the large number of pages used in the collection.

Of these, "collection to last ten thousand ages" is considered to be the interpretation with the most weight.[4]

Periodization

The collection is customarily divided into four periods. The earliest dates to prehistoric or legendary pasts, from the time of Emperor Yūryaku (r.?456–?479) to those of the little documented Emperor Yōmei (r.585–587), Saimei (r.594–661), and finally Tenji (r.668–671) during the Taika Reforms and the time of Fujiwara no Kamatari (614–669). The second period covers the end of the seventh century, coinciding with the popularity of Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, one of Japan's greatest poets. The third period spans 700–c.730 and covers the works of such poets as Yamabe no Akahito, Ōtomo no Tabito and Yamanoue no Okura. The fourth period spans 730–760 and includes the work of the last great poet of this collection, the compiler Ōtomo no Yakamochi himself, who not only wrote many original poems but also edited, updated and refashioned an unknown number of ancient poems.

Linguistic significance

In addition to its artistic merits the Man'yōshū is important for using one of the earliest Japanese writing systems, the cumbersome man'yōgana. Though it was not the first use of this writing system, which was also used in the earlier Kojiki (712), it was influential enough to give the writing system its name: "the kana of the Man'yōshū". This system uses Chinese characters in a variety of functions: their usual logographic sense; to represent Japanese syllables phonetically; and sometimes in a combination of these functions. The use of Chinese characters to represent Japanese syllables was in fact the genesis of the modern syllabic kana writing systems, being simplified forms (hiragana) or fragments (katakana) of the man'yōgana.

The collection, particularly volumes 14 and 20, is also highly valued by historical linguists for the information it provides on Japanese dialects.[5]

Translations

Julius Klaproth produced some early, severely flawed translations of Man'yōshū poetry. Donald Keene explained in a preface to the Nihon Gakujutsu Shinkō Kai edition of the Man'yōshū:

- "One 'envoy' (hanka) to a long poem was translated as early as 1834 by the celebrated German orientalist Heinrich Julius Klaproth (1783–1835). Klaproth, having journeyed to Siberia in pursuit of strange languages, encountered some Japanese castaways, fisherman, hardly ideal mentors for the study of 8th century poetry. Not surprisingly, his translation was anything but accurate."[6]

The Man'yōshū has been accepted in the Japanese Translation Series of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).[7]

Mokkan

A total of three wooden fragments known as mokkan (木簡) containing text from the Man'yōshū have been excavated:[8][9][10][11]

- From the archaeological site in Kizugawa, Kyoto. A 23.4 cm long, 2.4 cm wide, 1.2 cm deep fragment. Dated between 750 and 780, it contains the first eleven characters of poem #2205 (volume 10) written in Man'yōgana. Inspection with an infrared camera indicates other characters suggesting that it was used for writing practice

- From the Miyamachi archaeological site in Kōka, Shiga. A 2 cm wide, 1 mm deep fragment was discovered in 1997 and is dated to mid 8th century. It contains poem #3807 (volume 16).

- From the Ishigami archaeological site in Asuka, Nara. A 9.1 cm long, 5.5 cm wide, 6 mm deep fragment was found. Dated to the late 7th century, it is the oldest of the known Man'yōshū fragments. It contains the first 14 characters of poem #1391 (volume 7) written in Man'yōgana.

Others

More than 150 species of grasses and trees are included in 1500 entries of Man'yōshū. More than 30 of the species are found at the Man'yō Botanical Garden (万葉植物園 Manyō shokubutsu-en) in Japan, collectively placing them with the name and associated tanka for visitors to read and observe, reminding them of the ancient time in which the references were made. The first Manyo shokubutsu-en opened in Kasuga Shrine in 1932.[12][13]

See also

References

- ↑ Satake (2004: 555)

- ↑ Earl Miner; Hiroko Odagiri; Robert E. Morrell (1985). The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature. Princeton University Press. pp. 170–171. ISBN 0-691-06599-3.

- ↑ Uemura, Etsuko 1981 (24th edition, 2010). Man'yōshū-nyūmon p.17. Tokyo: Kōdansha Gakujutsu Bunko.

- ↑ Uemura 1981:17.

- ↑ Uemura 1981:25–26.

- ↑ Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkōkai. (1965). The Man'yōshū, p. iii.

- ↑ Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkōkai, p. ii.

- ↑ "7世紀の木簡に万葉の歌 奈良・石神遺跡、60年更新". Asahi. 2008-10-17. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "万葉集:3例目、万葉歌木簡 編さん期と一致--京都の遺跡・8世紀後半". Mainichi. 2008-10-23. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "万葉集:万葉歌、最古の木簡 7世紀後半--奈良・石神遺跡". Mainichi. 2008-10-18. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "万葉集:和歌刻んだ最古の木簡出土 奈良・明日香". Asahi. 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Manyo Shokubutsu-en(萬葉集に詠まれた植物を植栽する植物園)" (in Japanese). Nara: Kasuga Shrine. Archived from the original on 2009-08-05. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ↑ "Man'y Botanical garden(萬葉植物園)" (PDF) (in Japanese). Nara: Kasuga Shrine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-05. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

Bibliography and further reading

- texts and translations

- "Online edition of the Man'yōshū" (in Japanese). University of Virginia Library Japanese Text Initiative. Retrieved 2006-07-10. External link in

|publisher=(help) - Cranston, Edwin A. (1993). A Waka Anthology: Volume One: The Gem-Glistening Cup. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3157-8.

- Kodansha (1983). "Man'yoshu". Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. Kodansha.

- Honda, H. H. (tr.) (1967). The Manyoshu: A New and Complete Translation. The Hokuseido Press, Tokyo.

- Levy, Ian Hideo (1987). The Ten Thousand Leaves: A Translation of the Man'yoshu. Japan's Premier Anthology of Classical Poetry, Volume One. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00029-8.

- Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai (2005). 1000 Poems From The Manyoshu: The Complete Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai Translation. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43959-3.

- Suga, Teruo (1991). The Man'yo-shu : a complete English translation in 5–7 rhythm. Japan's Premier Anthology of Classical Poetry, Volume One. Tokyo: Kanda Educational Foundation, Kanda Institute of Foreign Languages. ISBN 4-483-00140-X., Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba City

- general

- Cranston, Edwin A. (1993). A Waka Anthology: Volume One: The Gem-Glistening Cup. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3157-8.

- Nakanishi, Susumu (1985). Man'yōshū Jiten (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Kōdansha. ISBN 4-06-183651-X.

- Satake, Akihiro; Hideo Yamada; Rikio Kudō; Masao Ōtani; Yoshiyuki Yamazaki (2004). Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei, Bekkan: Man'yōshū Sakuin (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-00-240105-7.

External links

- Man'yōshū – from the University of Virginia Japanese Text Initiative website

- Manuscript scans at Waseda University Library: 1709, 1858, unknown

- Man'yoshu - Columbia University Press, Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai translation 1940, 1965