Manuela Sáenz

| Doña Manuela Sáenz | |

|---|---|

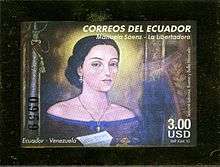

Libertadora del Libertador wearing the Order of the Sun medal | |

| Born |

December 27, 1797 Quito, Viceroyalty of New Granada (Present-day Ecuador) |

| Died |

November 23, 1856 (aged 58) Paita, Peru |

| Occupation | Revolutionary and spy |

| Spouse(s) | James Thorne (married 1817 – estranged 1822) |

| Partner(s) | Simón Bolívar (1822-1830) |

| Children | n/a |

| Parent(s) | Simón Sáenz Vergara and Maria Joaquina Aizpuru |

Doña Manuela Sáenz y Aizpuru (December 27, 1797 – November 23, 1856) was a revolutionary hero of South America who supported the revolutionary cause by gathering information, distributing leaflets, and protesting for women's rights. Manuela received the Order of the Sun ("Caballeresa del Sol" or 'Dame of the Sun'), honoring her services in the revolution.

Sáenz married a wealthy English merchant in 1817 and became a socialite in Lima, Peru. This provided the setting for involvement in political and military affairs, and she became active in support of revolutionary efforts. Leaving her husband in 1822, she soon began an eight-year collaboration and intimate relationship with Simón Bolívar that lasted until his death in 1830. After she prevented an 1828 assassination attempt against him and facilitated his escape, Bolívar began to call her "Libertadora del libertador" ("liberator of the liberator"). Manuela's role within the revolution after her death generally was overlooked until the late twentieth century, presently she is recognized as a feminist symbol of the 19th century wars of independence.

Life

Early life

Manuela was born in Quito, the illegitimate child of Maria Joaquina Aizpuru from Ecuador and the married Spanish nobleman Simón Sáenz Vergara (or Sáenz y Verega). Her mother was abandoned by her modest family as a result of the pregnancy and young "Manuelita" went to school at the Convent of Santa Catalina where she learned to read, and write. She was forced to leave the convent at the age of seventeen, when she was discovered to have been a victim of seduction by army officer Fausto D'Elhuyar, the nephew and son of Juan José and Fausto de Elhuyar y de Suvisa, who was one of the co-discoverers of tungsten.

Early participation within the revolution

For several years, Manuela lived with her father, who in 1817 arranged for her marriage to a wealthy English merchant, James Thorne, who was twice her age. The couple moved to Lima, Peru, in 1819 where she lived as an aristocrat and held social gatherings in her home where guests included political leaders and military officers. These guests shared military secrets about the ongoing revolution with her, and, in 1819, when Simón Bolívar took part in the successful liberation of New Granada, Manuela Sáenz became an active member in the conspiracy against the viceroy of Perú, José de la Serna e Hinojosa during 1820.[1]

Relationship with Simón Bolívar (1822 - 1830)

In 1822, Sáenz left her husband and traveled to Quito, where she met Simón Bolívar. She exchanged love letters with him, and visited him while he moved from one country to another. Manuela supported the revolutionary cause by gathering information, distributing leaflets, and protesting for women's rights. As one of the most prominent female figures of the wars for independence, Manuela received the Order of the Sun ("Caballeresa del Sol" or 'Dame of the Sun'), honoring her services in the revolution. During the first months of 1825 and from February to September 1826, she lived with Bolívar near Lima, but as the war continued, Bolívar was forced to leave. Manuela later followed him to Bogotá. On September 25, 1828, mutinous officers attempted to assassinate Bolívar, but with Manuela's help he was able to escape, which made him later call her "Libertadora del Libertador".

Bolívar left Bogotá in 1830 and died in Santa Marta from tuberculosis while he was in transit, leaving the country to exile. He had made no provision for Manuela. Francisco de Paula Santander, who returned to power after Bolívar's death then exiled Manuela. She went to Jamaica for the early years of her exile.[1]

Years in exile and death (1835 - 1856)

When she attempted to return to Ecuador in 1835, the Ecuadorian president, Vicente Rocafuerte, revoked her passport. She then took refuge in northern Peru, living in the small coastal town of Paita. For the next twenty-five years, a destitute outcast, Manuela sold tobacco and translated letters for North American whale hunters who wrote to their lovers in Latin America. While there, she met the American author Herman Melville, and the revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi.

In 1847, her husband was murdered in Pativilca and she was denied her 8,000 pesos inheritance. Disabled after the stairs in her home collapsed, Manuela died in Paita, on November 23, 1856, during a diphtheria epidemic. Her body was buried in a communal, mass grave and her belongings were burned. The items that did survive, personal letters and artifacts, contributed later to the legacy of both her and Simon Bolívar.

On his deathbed, Bolívar had asked his aide-de-camp, General Daniel F. O'Leary to burn the remaining, extensive archive of his writings, letters, and speeches. O'Leary disobeyed the order and his writings survived, providing historians with a vast wealth of information about Bolívar's liberal philosophy and thought, as well as details of his personal life, such as his longstanding love affair with Manuela Sáenz. Shortly before her own death in 1856, Sáenz augmented this collection by giving O'Leary her own letters from Bolívar.[1]

Recognition and 2010 reburial

On July 5, 2010, Manuela Sáenz was given a full state burial in Venezuela. Because she had been buried in a mass grave, no official remains of her existed for the state burial; instead, "symbolic remains", composed of some soil from the mass grave into which she was buried during the epidemic, were transported through Peru, Ecuador and Colombia to Venezuela. Those remains were laid in the National Pantheon of Venezuela where those Bolívar are also memorialized.

Legacy

After the revolution, Manuela effectively faded within literature. Between 1860-1940 only three Ecuadorian writers wrote about her and her participation within the revolution,[2] and these writings largely portrayed her as either exclusively the lover of Simón Bolívar or as incapable and wrongfully participating within the political sphere. These portrayals also assured her femininity as a mainstay of her characterization.[2] However, the 1940s created a significant shift in how she was viewed and characterized. Literature like Papeles De Manuela Saenz, 1945, by Vicente Lecuna, which was a compilation of documents regarding the life of Bolívar, effectively disproved popular stereotypes about Manuela.[2] Ideas about her being sexually deviant, hyper feminine and incapable were replaced by more favorable portrayals as the 20th century progressed.

The later 20th century generated shifts in her portrayals that were consistent with ideological shifts within Latin America, like the increase of feminism of the 1980s and nationalism of the 1960s - 1970’s. Portrayals within the fictional The General in His Labyrinth by Gabriel García Márquez and the nonfictional Alfonso Rumazo’s Manuela Saenz La Libertedora del Libertador contributed to her effective humanization within popular culture and helped politicize her image.[3] Alfonso Rumazo’s novel was especially poignant for its ideas of Pan-American Nationalism that were represented through Manuela’s participation within the wars of independence. Manuela became increasingly popular with radical Latin American feminist groups subsequently, her image was commonly used as a rallying point for Indo-Latina causes of the 1980s.[3] The popular image of Manuela riding horseback in men’s clothing, popularized by her portrayal in The General in His Labyrinth, was re-enacted by female demonstrators in Ecuador in 1998.[3]

On May 25, 2007 the Ecuadorian government symbolically gave Saenz the rank of General.[3]

Museo Manuela Sáenz

The Museo Manuela Sáenz is a museum in Old Town, Quito, that contains personal effects from both Sáenz and Bolívar in order to "[safeguard] the memories of Manuela Saenz, Quito's illustrious daughter".[4] Located at Junin 709 y Montufar, Centro Histórico, Quito. Entrance to the museum is free with the purchase of one of the books about Manuela's life. Personal effects within the museum include letters, stamps, and paintings.

Biographical writings

- "The Four Seasons of Manuela". Biography by Victor Wolfgang von Hagen (1974)

- "Manuela". Novel by Gregory Kauffman (1999). ISBN 978-0-9704250-0-3

- "Manuela Sáenz – La Libertadora del Libertador". Author: Alfonso Rumazo González (Quito 1984)

- "En Defensa de Manuela Sáenz". Authors: Pablo Neruda, Ricardo Palma, Victor von Hagen, Vicente Lecuma, German Arciniegas, Alfonso Rumazo, Pedro Jorge Vera, Jorge Salvador Lara, Jorge Enrique Adoum, Mario Briceño Perozo, Mary Ferrero, Benjamín Carrión, Jorge Villalba S.J., Leonardo Altuve, Juan Liscano (Quito)

- "Manuela Sáenz – presencia y polémica en la historia". Authors: María Mogollón and Ximena Narváez (Quito 1997)

- "la Vida Ardiente De Manuelita Sáenz". Author: Alberto Miramón (Bogota 1946)

- For Glory and Bolívar: The Remarkable Life of Manuela Sáenz. Biography by Pamela S. Murray. (Austin, TX 2008). ISBN 978-0-292-71829-6

- Our Lives Are the Rivers: A Novel. Author: Jaime Manrique.

Biographical movies and opera

- Manuela Sáenz, directed by Diego Rísquez (2000) 97 minutes.

- Manuela y Bolívar, opera in two acts by composer/librettist Diego Luzuriaga (2006) 2-1/2 hours.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manuela Sáenz. |

- 1 2 3 Bolívar, Simón (1983). Hope of the universe (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 9231021036.

- 1 2 3 Murray, Pamela S. (2001). "Loca' or 'Libertadora'?: Manuela Sáenz in the Eyes of History and Historians, 1900-c.1990.". Journal of Latin American Studies. 33: 291–310 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 3 4 Murray, Pamela (2008). For Glory and Bolívar. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 156–160. ISBN 978-0292721517.

- ↑ "Museo Manuela Sáenz | Quito | Museums & Galleries | eventseeker". eventseeker.com. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

Cited sources

- Arismendi Posada, Ignacio (1983). Gobernantes Colombianos [Colombian Presidents] (second ed.). Bogotá, Colombia: Interprint Editors Ltd.; Italgraf.