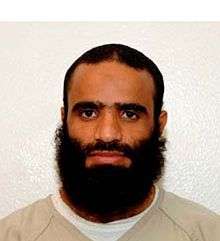

Mansur Ahmad Saad al-Dayfi

| Mansur Ahmad Saad al-Dayfi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Released |

2016-07-11 Serbia |

| Citizenship | Yemen |

| Detained at | Guantanamo |

| Alternate name |

|

| ISN | 441 |

| Charge(s) | no charge, extrajudicial detention |

| Status | given asylum in Serbia |

Mansur Ahmad Saad al-Dayfi is a citizen of Yemen who was held, without charge, in the United States Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba, from February 9, 2002, to July 11, 2016.[1] On July 11, 2016 he and a Tajikistani captive were transferred to Serbia.[2][3]

His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number is 441.[1] JTF-GTMO analysts estimate he was born in 1979, in Sana'a, Yemen.

According to the Washington Post the allegations against Al Zahri are internally inconsistent.[4][5]

Official status reviews

Originally the Bush Presidency asserted that captives apprehended in the "war on terror" were not covered by the Geneva Conventions, and could be held indefinitely, without charge, and without an open and transparent review of the justifications for their detention.[6] In 2004 the United States Supreme Court ruled, in Rasul v. Bush, that Guantanamo captives were entitled to being informed of the allegations justifying their detention, and were entitled to try to refute them.

Office for the Administrative Review of Detained Enemy Combatants

Following the Supreme Court's ruling the Department of Defense set up the Office for the Administrative Review of Detained Enemy Combatants.[6][9]

Scholars at the Brookings Institution, led by Benjamin Wittes, listed the captives still held in Guantanamo in December 2008, according to whether their detention was justified by certain common allegations:[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... are members of Al Qaeda."[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... traveled to Afghanistan for jihad."[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges that the following detainees stayed in Al Qaeda, Taliban or other guest- or safehouses."[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... took military or terrorist training in Afghanistan."[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... fought for the Taliban."[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives whose "names or aliases were found on material seized in raids on Al Qaeda safehouses and facilities."[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives who was a member of the "al Qaeda leadership cadre".[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of "36 [captives who] openly admit either membership or significant association with Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or some other group the government considers militarily hostile to the United States."[10]

- Abd Al Rahman Al Zahri was listed as one of the captives who had admitted "to training at Al Qaeda or Taliban camps".[10]

Formerly secret Joint Task Force Guantanamo assessment

On April 25, 2011, whistleblower organization WikiLeaks published formerly secret assessments drafted by Joint Task Force Guantanamo analysts.[11][12] His thirteen-page Joint Task Force Guantanamo assessment was drafted on June 9, 2008.[13] It was signed by camp commandant Rear Admiral David M. Thomas Jr., who recommended continued detention.

Transfer to Serbia

Al Dayfi was transferred to Serbia, together with an individual from Tajikistan, named "Muhammadi Davlatov".[2]

PBS Frontline profile

On February 21, 2017, Al-Dayfi was profiled in an episode of the PBS network's Frontline series.[14][15] His habeas attorney, Beth Jacobs, described how al-Dayfi was offered either Serbia or continued detention.

Jacobs said that neither Serbia, or the US, had provided him with any language training, or other support to help him adapt to civilian life, or adjust to living in a foreign culture, or help him find employment, and that he had started a hunger strike in consequence.[14]

Al-Dayfi learned English in Guantanamo.[14]

When Frontline visited al-Dayfi his weight had dropped 18 pounds in 21 days.[14] In Guantanamo he had been continuously force-fed for over two years.

Frontline producers were intercepted by security officials.[14]

During the course of their research al-Dayfi disappeared.[14] Serbian security officials interfered with their access to him.

References

- 1 2 OARDEC. "List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through May 15, 2006" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-05-15.

Works related to List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through May 15, 2006 at Wikisource

Works related to List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through May 15, 2006 at Wikisource

- 1 2 "Guantanamo Bay: US transfers two detainees to Serbia, Pentagon says". Australian Broadcasting Network. 2016-07-11. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

US defence, homeland security and other officials determined late last year that continued imprisonment of al-Dayfi "does not remain necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States".

- ↑ Margot Williams (2008-11-03). "Guantanamo Docket: Abdul Rahman Ahmed". New York Times. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ↑ Peter Finn (2009-02-16). "4 Cases Illustrate Guantanamo Quandaries: Administration Must Decide Fate of Often-Flawed Proceedings, Often-Dangerous Prisoners". Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ Peter Finn (2009-02-21). "Administration Must Decide Fate of Often-Flawed Proceedings, Often-Dangerous Prisoners". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2016-07-11.

Zahri has refused to meet with his attorneys, who said they were unable to discuss his case in any detail because much of the material about him remains classified. But they raised the possibility that his statements may have been coerced and cautioned that his sometimes contradictory remarks -- condemning bin Laden at one hearing and pledging fealty to him at another, threatening the United States and then saying he has "no issue" with America -- make anything he has said at Guantanamo Bay unreliable.

- 1 2 "U.S. military reviews 'enemy combatant' use". USA Today. 2007-10-11. Archived from the original on 2012-08-11.

Critics called it an overdue acknowledgment that the so-called Combatant Status Review Tribunals are unfairly geared toward labeling detainees the enemy, even when they pose little danger. Simply redoing the tribunals won't fix the problem, they said, because the system still allows coerced evidence and denies detainees legal representation.

- ↑ Neil A. Lewis (2004-11-11). "Guantánamo Prisoners Getting Their Day, but Hardly in Court". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- ↑ Mark Huband (2004-12-11). "Inside the Guantánamo Bay hearings: Barbarian "Justice" dispensed by KGB-style "military tribunals"". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- ↑ "Q&A: What next for Guantanamo prisoners?". BBC News. 2002-01-21. Archived from the original on 24 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Benjamin Wittes, Zaathira Wyne (2008-12-16). "The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study" (PDF). The Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 2012-06-22. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ↑ Christopher Hope; Robert Winnett; Holly Watt; Heidi Blake (2011-04-27). "WikiLeaks: Guantanamo Bay terrorist secrets revealed -- Guantanamo Bay has been used to incarcerate dozens of terrorists who have admitted plotting terrifying attacks against the West – while imprisoning more than 150 totally innocent people, top-secret files disclose". The Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

The Daily Telegraph, along with other newspapers including The Washington Post, today exposes America’s own analysis of almost ten years of controversial interrogations on the world’s most dangerous terrorists. This newspaper has been shown thousands of pages of top-secret files obtained by the WikiLeaks website.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks: The Guantánamo files database". The Telegraph (UK). 2011-04-27. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- ↑ "Abd Al Rahman Ahmed Said Abdihi: Guantanamo Bay detainee file on Abd Al Rahman Ahmed Said Abdihi, US9YM-000441DP, passed to the Telegraph by Wikileaks". The Telegraph (UK). 2011-04-27. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Out of Gitmo". Frontline (PBS). 2017-02-21. Archived from the original on 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- ↑ Arun Rath (2017-02-21). "'Out Of Gitmo': Released Guantanamo Detainee Struggles In His New Home". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

I traveled to Serbia and met Mansoor al-Dayfi, who had been sent to Guantanamo Bay soon after the war-on-terrorism detention facility was opened in early 2002.

External links

- Who Are the Remaining Prisoners in Guantánamo? Part Two: Captured in Afghanistan (2001) Andy Worthington, September 17, 2010