Trebuchet

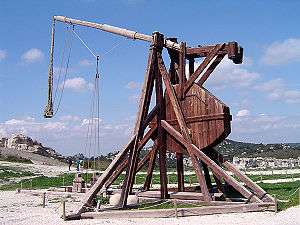

A trebuchet[nb 1] (French trébuchet) is a type of siege engine which uses a swinging arm to throw a projectile at the enemy.

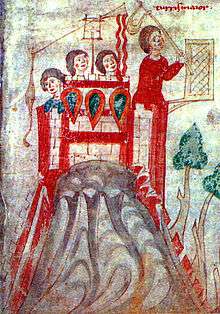

The traction trebuchet first appeared in China during the 4th century BC as a siege weapon. It spread westward, probably by the Avars, and was adopted by the Byzantines in the mid 6th century AD. It uses manpower to swing the arm.

The later counterweight trebuchet, also known as the counterpoise trebuchet, uses a counterweight to swing the arm. It appeared in both Christian and Muslim lands around the Mediterranean in the 12th century, and made its way back to China via Mongol conquests in the 13th century.

When used without further specification, the counterweight trebuchet is normally meant.

Basic design

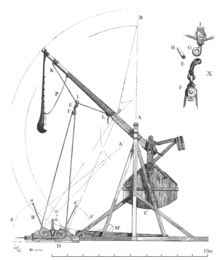

The trebuchet is a compound machine that makes use of the mechanical advantage of a lever to throw a projectile. They are typically large constructions (up to 100 feet [30 meters] in height or more) made primarily of wood, usually reinforced with metal, leather, rope, and other materials. They are usually immobile and must be assembled on-site, possibly making use of local lumber with only key parts brought with the army to the site of the siege or battle.

A trebuchet consists primarily of a long beam attached by an axle to a stout frame and base, such that the beam can rotate vertically through a wide arc (typically over 180°). A sling is attached to one end of the beam to hold the projectile. The projectile is thrown when the beam is quickly rotated by applying force to the opposite end of the beam. The mechanical advantage is primarily obtained by having the projectile end of the beam much longer — usually four to six times the length of the force-applied end.[3]

Counterweight trebuchets are powered by gravity; potential energy is stored by slowly raising an extremely heavy weight box (typically filled with stones, sand, or lead) attached by a hinged connection to the shorter end of the beam, and releasing it on command. Traction trebuchets are human powered; on command, men pull ropes attached to the shorter end of the trebuchet beam. The difficulties of coordinating the pull of very many men together repeatedly and predictably makes counterweight trebuchets preferable for the larger machines, though they are more complicated to engineer.[4]

When the trebuchet is loosed, the force causes rotational acceleration of the beam around the axle (the fulcrum of the lever). These factors multiply the acceleration transmitted to the throwing portion of the beam and its attached sling. The sling transmits the forces generated by the beam rotation to the projectile. The length of the sling increases the mechanical advantage, and also changes the trajectory so that, at the time of release from the sling, the projectile is traveling in the desired speed and angle to give it the range to hit the target.

The rotation speed of the throwing beam increases smoothly until it reaches maximum rotation speed (usually about the time when the projectile is released). Then the arm continues to rotate, slowing, coming to rest at the end of the rotation rather smoothly. This is unlike the violent sudden start and stop inherent in the action of other siege engine designs such as the onager. This key difference makes the trebuchet much more durable, allowing for larger and more powerful machines.

A trebuchet projectile can be almost anything, even debris, corpses, or incendiaries, but is typically a large stone. Dense stone, or even metal, specially worked to be round and smooth, gives the best range and predictability. When attempting to breach enemy walls, it is important to use materials that wouldn't shatter on impact; projectiles were sometimes brought from distant quarries to get the desired properties.[5]

The couillard is a smaller version of a counterweight trebuchet with a single frame instead of the usual double "A" frames. The counterweight is split into two halves to avoid hitting the center frame.[6]

History

Traction trebuchet

The trebuchet is thought to have originated in ancient China.[7][8][9] Torsion-based siege weapons such as catapults are not known to have been used in China.[10]

The first recorded use of traction trebuchets appeared in ancient China and were probably used by the Mohists as early as 4th century BC, descriptions of which can be found in the Mojing (compiled in the 4th century BC).[8][9] The trebuchet was carried westward by the Avars and appeared next in the eastern Mediterranean by the late 6th century AD.[7][11] The Byzantines adopted the traction trebuchet possibly as early as 587.[10] In China the traction trebuchet continued to be used until the counterweight trebuchet was introduced during the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty. In 617 Li Mi (Sui dynasty) constructed 300 trebuchets for his assault on Luoyang, in 621 Li Shimin did the same at Luoyang, and onward into the Song dynasty when in 1161, trebuchets operated by Song dynasty soldiers fired bombs of lime and sulphur against the ships of the Jin dynasty navy during the Battle of Caishi.[12][13]

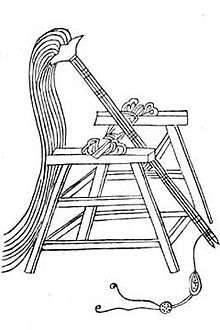

Hand-trebuchet

The hand-trebuchet (Greek: cheiromangana) was a staff sling mounted on a pole using a lever mechanism to propel projectiles. Basically a one-man traction trebuchet, it was used by emperor Nikephoros II Phokas around 965 to disrupt enemy formations in the open field. It was also mentioned in the Taktika of general Nikephoros Ouranos (c. 1000), and listed in De obsidione toleranda (author anonymous) as a form of artillery.[14]

Counterweight trebuchet

.jpg)

The first record of a counterweight trebuchet was in the 12th century from Mardi ibn Ali al-Tarsusi while talking of the conquests of Saladin.[15][16] The next record of the counterweight trebuchet appears in the work of the 12th century Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates. Niketas describes a trebuchet used by Andronikos I Komnenos, future Byzantine emperor, at the siege of Zevgminon in 1165 which was equipped with a windlass, which is useful only for counterweight trebuchets.[17] Chevedden dates the invention of the new artillery type back to the Siege of Nicaea in 1097 when the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos, an ally of the besieging crusaders, was reported to have invented new pieces of heavy artillery which deviated from the conventional design and made a deep impression on everyone.[18]

The dramatic increase in military performance is for the first time reflected in historical records on the occasion of the second siege of Tyre in 1124, when the crusaders reportedly made use of "great trebuchets".[19] By the 1120–30s, the counterweight trebuchet had diffused not only to the crusader states, but probably also westwards to the Normans of Sicily and eastwards to the Great Seljuqs. The military use of the new gravity-powered artillery culminated in the 12th century during the Siege of Acre (1189–91) which saw the kings Richard I of England and Philip II of France wrestle for control of the city with Saladin's forces.[20]

During the Crusades, Philip II of France named two of the trebuchets he used in the Siege of Acre in 1191 "God's Stone-Thrower" and "Bad Neighbour."[21] During a siege of Stirling Castle in 1304, Edward Longshanks ordered his engineers to make a giant trebuchet for the English army, named "Warwolf". Range and size of the weapons varied. In 1421 the future Charles VII of France commissioned a trebuchet (coyllar) that could shoot a stone of 800 kg, while in 1188 at Ashyun, rocks up to 1,500 kg were used. Average mass of the projectiles was probably around 50–100 kg, with a range of c. 300 meters. The cycle rate could be noteworthy: at the siege of Lisbon (1147), two engines were capable of launching a stone every 15 seconds. Also human corpses could be used on special occasion: in 1422 Prince Korybut, for example, in the siege of Karlštejn Castle shot men and manure within the enemy walls, apparently managing to spread infection among the defenders. The largest trebuchets needed exceptional quantities of timber: at the Siege of Damietta, in 1249, Louis IX of France was able to build a stockade for the whole Crusade camp with the wood from 24 captured Egyptian trebuchets.

Counterweight trebuchets do not appear with certainty in Chinese historical records until about 1268, when the Mongols laid siege to Fancheng and Xiangyang. At the Siege of Fancheng and Xiangyang, the Mongol army, unable to capture the cities despite besieging the Song defenders for years, brought in two Persian engineers who built hinged counterweight trebuchets. These engines were called by the Chinese historians the Huihui trebuchet (回回砲, where "huihui" is a loose slang referring to any Muslims), or Xiangyang trebuchet (襄陽砲) because they were first encountered in that battle. After Aju asked Kublai, the Emperor of the Mongol Empire, to help him with the powerful siege machines of the Ilkhanate, Ismail and Al-aud-Din from Iraq arrived in South China to construct a new type of trebuchet. These Persian engineers built mangonels and trebuchets for the siege.[22] Chinese and Muslim engineers operated Artillery and siege engines for the Mongol armies.[23] The design was taken from those used by Hulegu to batter down the walls of Baghdad. The Chinese were the inventors of the traction trebuchet, but now they faced Muslim-designed counterweight trebuchets in the Mongol army. The Chinese responded by building their own counterweight trebuchets.[24]

With the introduction of gunpowder, the trebuchet lost its place as the siege engine of choice to the cannon. Trebuchets were used both at the siege of Burgos (1475–1476) and siege of Rhodes (1480). One of the last recorded military uses was by Hernán Cortés, at the 1521 siege of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán. Accounts of the attack note that its use was motivated by the limited supply of gunpowder. The attempt was reportedly unsuccessful: the first projectile landed on the trebuchet itself, destroying it.[25]

Modern use

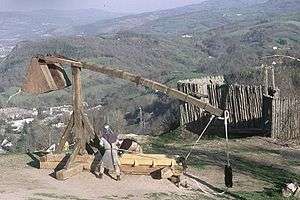

Recreation and education

Most trebuchet use in recent centuries has been for recreational or educational, rather than military purposes. New machines have been constructed and old ones restored by living history enthusiasts, for historical re-enactments, and use in other historical celebrations. As their construction is substantially simpler than modern weapons, trebuchets also serve as the object of engineering challenges.[26][27]

The trebuchet's technical constructions were lost at the beginning of the 16th century. In 1984, the French engineer Renaud Beffeyte made the first modern reconstruction of a trebuchet, based on documents from 1324.[28]

The largest currently-functioning trebuchet in the world is the 22-tonne machine at Warwick Castle, England. Based on historical designs, it stands 18 metres (59 ft) tall and throws missiles typically 36 kg (80 lbs) up to 300 metres (980 ft). It is built on the design of a similar trebuchet at Middelaldercentret in Denmark.[29] In 1989, Middelaldercentret became the first place in the modern era to have a working trebuchet.[29]

Trebuchets compete in one of the classifications of machines used to hurl pumpkins at the annual pumpkin chunking contest held in Sussex County, Delaware, U.S. The record-holder in that contest for trebuchets is the Yankee Siege II from New Hampshire, which at the 2013 WCPC Championship tossed a pumpkin 2835.8 ft (864.35 metres). The 51-foot-tall (16 m), 55,000-pound (25,000 kg) trebuchet flings the standard 8–10-pound (3.6–4.5 kg) pumpkins,[30] specified for all entries in the WCPC competition.

Developments

Although rarely used as a weapon today, trebuchets maintain the interest of professional and hobbyist engineers. One modern technological development, especially for the competitive pumpkin-hurling events, is the "floating arms" design.[31] Instead of using the traditional axle fixed to a frame, these devices are mounted on wheels that roll on a track parallel to the ground, with a counterweight that falls directly downward upon release, allowing for greater efficiency by increasing the proportion of energy transferred to the projectile.[32]

Uses in activism and insurgency

In 2013, during the Syrian civil war, rebels were filmed using a trebuchet in the Battle of Aleppo.[33] The trebuchet was used to project explosives at government troops.[34]

In 2014, during the Hrushevskoho street riots in Ukraine, rioters used an improvised trebuchet to throw bricks and molotov cocktails at the Berkut.[35]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Pronounced /ˈtrɛbəʃɛt/ TREB-ə-shet or /ˌtrɛbjʊˈʃɛt/ TREB-yuu-SHET;[1] also spelled trebucket /ˈtriːbʌkɪt/ TREE-buk-it or /ˌtrɛbjʊˈkɛt/ TREB-yuu-KET[2]

References

- ↑ OED, Random House Unabridged Dictionary

- ↑ Random House Unabridged Dictionary

- ↑ Saimre 2007, p. 65.

- ↑ Saimre 2007, p. 64.

- ↑ Saimre 2007, p. 73.

- ↑ Max (19 May 2015). "Trebuchet Design Factors".

- 1 2 Chevedden, Paul E.; et al. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American: 66–71. http://static.sewanee.edu/physics/PHYSICS103/trebuchet.pdf. Original version.

- 1 2 The Trebuchet, Citation:"The trebuchet, invented in China between the fifth and third centuries B.C.E., reached the Mediterranean by the sixth century C.E. "

- 1 2 PAUL E. CHEVEDDEN, The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion, p.71, p.74, See citation:"The traction trebuchet, invented by the Chinese sometime before the fourth century B.C." in page 74

- 1 2 Graff 2016, p. 86.

- ↑ Graff 2016, p. 141.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1987). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Volume 5, Part 7. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- ↑ Franke, Herbert (1994). Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ↑ Chevedden 2000, p. 110

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim (1992). The Medieval Siege. The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-312-7.

- ↑ "Arms and Men: The Trebuchet". Historynet.com. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ↑ Chevedden 2000, p. 86

- ↑ Chevedden 2000, pp. 76–86; 110f.

- ↑ Chevedden 2000, p. 92

- ↑ Chevedden 2000, pp. 104f.

- ↑ "Historic Trebuchets – Acre 1191", IInet.net.au

- ↑ Jasper Becker (2008). City of heavenly tranquility: Beijing in the history of China (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0195309979. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ René Grousset (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia (reprint ed.). Rutgers University Press. p. 283. ISBN 0813513049. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Stephen R. Turnbull (2003). Genghis Khan & the Mongol conquests, 1190-1400 (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 1841765236. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ Chevedden 1995, p. 5

- ↑ "Thelep.org.uk". Thelep.org.uk. 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ↑ "Wright.edu". Engineering.wright.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ↑ "armedieval - le trebuchet et les machines civiles et militaires médiévales".

- 1 2 June 14, 2005 Reconstructing Medieval Artillery. archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved 12 September 2013

- ↑ "World Championship Punkin Chunkin-Current World Records". punkinchunkin.com. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ↑ Punkin Chunkin 2010- Tired Iron (YouTube). Hancock, NH USA: The Science Channel. November 24, 2010. Event occurs at 1:17. Archived from the original (Youtube) on November 24, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ RLT Industries. "The Original Floating Arm Trebuchet". Trebuchet.com. New Braunfels, TX. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ↑ YouTube.

- ↑ Syrian opposition use medieval 'trebuchet' to launch bombs - Truthloader. 22 February 2013 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Ukrainian Protesters Built A Giant Catapult To Fight The Riot Police". BuzzFeed. 20 January 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

Bibliography

- Chevedden, Paul E.; et al. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet" (PDF). Scientific American: 66–71.. Original version.

- Chevedden, Paul E. (2000). "The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 54: 71–116. JSTOR 1291833. doi:10.2307/1291833.

- Dennis, George (1998). "Byzantine Heavy Artillery: The Helepolis". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies (39).

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Gravett, Christopher (1990). Medieval Siege Warfare. Osprey Publishing.

- Hansen, Peter Vemming (April 1992). "Medieval Siege Engines Reconstructed: The Witch with Ropes for Hair". Military Illustrated (47): 15–20.

- Hansen, Peter Vemming (1992). "Experimental Reconstruction of the Medieval Trebuchet". Acta Archaeologica (63): 189–208.

- Jahsman, William E.; MTA Associates (2000). The Counterweighted Trebuchet – an Excellent Example of Applied Retromechanics.

- Jahsman, William E.; MTA Associates (2001). FATAnalysis (PDF).

- Archbishop of Thessalonike, John I (1979). Miracula S. Demetrii, ed. P. Lemerle, Les plus anciens recueils des miracles de saint Demitrius et la penetration des slaves dans les Balkans. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Liang, Jieming (2006). Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity – An Illustrated History.

- Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilization in China. Cambridge University Press. p. 218.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Payne-Gallwey, Sir Ralph (1903). "LVIII The Trebuchet". The Crossbow With a Treatise on the Balista and Catapult of the Ancients and an Appendix on the Catapult, Balista and Turkish Bow (Reprint ed.). pp. 308–315.

- Saimre, Tanel (2007), Trebuchet – a gravity operated siege engine. A Study in Experimental Archaeology (PDF)

- Siano, Donald B. (November 16, 2013). Trebuchet Mechanics (PDF).

- Al-Tarsusi (1947). Instruction of the masters on the means of deliverance from disasters in wars. Bodleian MS Hunt. 264. ed. Cahen, Claude, "Un traite d'armurerie compose pour Saladin". Bulletin d'etudes orientales 12 [1947–1948]:103–163.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trebuchets. |

| Look up trebuchet in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Trébuchet. |

- Secrets of Lost Empires: Medieval Siege (building of and history of trebuchets), from the NOVA website

- Warwick trebuchet

- Video Demonstration of the Medieval Siege Society's trebuchet

- Caerphilly Castle trebuchet shooting

- Trebuchet animation

- Trebuchet plans

- Virtual Trebuchet

- Trebuchet de l'AMQ a St-Marcellin on YouTube

- Slow motion mini trebuchet on YouTube

- Traction Trebuchet hurling a football on YouTube

- Super Trebuchets - A website about trebuchets with particular focus on modern uses and developments.