Manila

| Manila Maynilà | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital City | |||

|

From top, left to right: The Manila skyline, Manila Central Post Office, Manila City Hall, Rizal Monument, Binondo, Malacañang Palace, Manila Bay sunset; Tondo Church | |||

| |||

|

Nickname(s): Pearl of the Orient Queen City of The Pacific Paris of Asia[1] The City of Our Affections Distinguished and Ever Loyal City | |||

| Motto: Forward Ever, Backward Never | |||

Location within Metro Manila | |||

.svg.png) Manila Location within the Philippines | |||

| Coordinates: 14°35′N 121°00′E / 14.58°N 121°ECoordinates: 14°35′N 121°00′E / 14.58°N 121°E | |||

| Country | Philippines | ||

| Region | National Capital Region | ||

| District | 1st to 6th districts of Manila | ||

| Bruneian Empire (Kingdom of Maynila) | 1500s | ||

| Spanish Manila | June 24, 1571 | ||

| Highly Urbanized City | December 22, 1979 | ||

| Barangays | 896 | ||

| Government[2] | |||

| • Type | Mayor–council | ||

| • Mayor | Joseph Estrada (PMP) | ||

| • Vice Mayor | Honey Lacuña Pangan (Asenso Manileño) | ||

| • City Representatives |

List

| ||

| • City Council |

Councilors

| ||

| Area[3][4] | |||

| • City | 42.88 km2 (16.56 sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 1,474.82 km2 (569.43 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 613.94 km2 (237.04 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) | ||

| Population (2015 census)[5] | |||

| • City | 1,780,148 | ||

| • Density | 42,000/km2 (110,000/sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 22,710,000[6] | ||

| • Metro | 12,877,253 | ||

| • Metro density | 21,000/km2 (54,000/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) |

English: Manileño, Manilan; Spanish: manilense,[7] manileño(-a) Filipino: Manileño(-a), Manilenyo(-a), Taga-Maynila | ||

| Time zone | PST (UTC+8) | ||

| ZIP code | +900 - 1-096 | ||

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)2 | ||

| Website |

manila | ||

Manila (/məˈnɪlə/; Filipino: Maynilà, pronounced [majˈnilaʔ] or [majniˈla]), officially the City of Manila (Filipino: Lungsod ng Maynilà [luŋˈsod nɐŋ majˈnilaʔ]), is the capital of the Philippines and the most densely populated city proper in the world.[3] It was the first chartered City by virtue of the Philippine Commission Act 183 on July 31, 1901 and gained autonomy with the passage of Republic Act No. 409 or the "Revised Charter of the City of Manila" on June 18, 1949.[8]

Spanish Manila was founded on June 24, 1571, by Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi, it is one of the oldest cities in the Philippines and was the seat of power for most of the country's colonial rulers. It is situated on the eastern shore of Manila Bay and is home to many landmarks, some of which date back to the 16th century. In 2016, the Globalization and World Cities Research Network listed Manila as an alpha- global city.[9] The city proper is home to 1,780,148 people in 2015[5], and is the historic core of a built-up area that extends well beyond its administrative limits. The term "Manila" is commonly used to refer to the whole metropolitan area, the greater metropolitan area or the city proper. The officially-defined metropolitan area called Metro Manila, the capital region of the Philippines, includes the much larger Quezon City and the Makati Central Business District. It is the most populous region of the country, one of the most populous urban areas in the world,[10] and is one of the wealthiest regions in Southeast Asia.[11][12] With 41,515 people per square kilometer, Manila is also the most densely populated city proper in the world. [5][3]

Manila is located on the eastern shores of the Manila Bay in one of the finest harbors in the country. The Pasig River runs through the middle of the city. Manila is made up of 16 districts: Binondo, Ermita, Intramuros, Malate, Paco, Pandacan, Port Area, Quiapo, Sampaloc, San Andres, San Miguel, San Nicolas, Santa Ana, Santa Cruz, Santa Mesa and Tondo. Manila is also made up of Six Congressional Districts that represents the city on the Lower House of the Philippine Congress.

Etymology

Maynilà, the Filipino name for the city, originated from the word nilà, referring to a flowering mangrove tree that grew on the delta of the Pasig River and the shores of Manila Bay. The flowers were made into garlands that, according to folklore, were offered to statues on religious altars or in churches.[13] As nilà products were distributed in other places, people came to refer to the area as "Sa may Nilà", Tagalog for "the place where there are nilàs". The word nilà itself is probably from the Sanskrit nila (नील), meaning "indigo tree".[14]

History

Precolonial history

The earliest evidence of human life around present-day Manila is the nearby Angono Petroglyphs, dated to around 3000 BC. Negritos, an Australoid people who became the aboriginal inhabitants of the Philippines, lived across the island of Luzon, where Manila is located, before the Malayo-Polynesians migrated in and assimilated them.[15]

The Kingdom of Tondo flourished during the latter half of the Ming dynasty as a result of direct trade relations with China. The Tondo district was the traditional capital of the empire, and its rulers were sovereign kings, not mere chieftains. They were addressed variously as panginuan in Maranao or panginoón in Tagalog ("lords"); anák banwa ("son of heaven"); or lakandula ("lord of the palace"). The Emperor of China considered the Lakans—the rulers of ancient Manila—"王", or kings.[16]

In the 13th century, Manila consisted of a fortified settlement and trading quarter on the shore of the Pasig River. It was then settled by the Indianized empire of Majapahit, as recorded in the epic eulogy poem "Nagarakretagama", which described the area's conquest by Maharaja Hayam Wuruk.[16] Selurong (षेलुरोन्ग्), a historical name for Manila, is listed in Canto 14 alongside Sulot, which is now Sulu, and Kalka.[16]

During the reign of Sultan Bolkiah from 1485 to 1521, the Sultanate of Brunei invaded, wanting to take advantage of Tondo's trade with China by attacking its environs and establishing the Kingdom of Maynilà (كوتا سلودوڠ; Kota Seludong). The kingdom was ruled under and gave yearly tribute to the Sultanate of Brunei as a satellite state.[17] It established a new dynasty under the local leader, who accepted Islam and became Rajah Salalila or Sulaiman I. He established a trading challenge to the already rich House of Lakan Dula in Tondo. Islam was further strengthened by the arrival of Muslim traders from the Middle East and Southeast Asia.[18] In 1574, Manila was temporarily besieged by the Chinese pirate Lim Hong, who was ultimately thwarted by the local inhabitants. The city then became the seat of the Spanish colonial government.

Spanish period

On June 24, 1571, the conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in Manila and declared it a territory of New Spain, establishing a city council in what is now the district of Intramuros.[19] López de Legazpi had the local royalty executed or exiled after the failure of the Tondo Conspiracy, a plot wherein an alliance between datus, rajahs, Japanese merchants and the Sultanate of Brunei would band together to execute the Spaniards, along with their Latin American mercenaries. The victorious Spaniards made Manila, the capital of the Spanish East Indies and of the Philippines, which their empire would control for the next three centuries.

Manila became famous during the Manila–Acapulco galleon trade, which lasted for three centuries and brought goods from Europe, Africa and Hispanic America across the Pacific Islands to Southeast Asia (which was already an entrepôt for goods coming from India, Indonesia and China), and vice versa. Silver that was mined in Mexico and Peru was exchanged for Chinese silk, Indian gems and the spices of Southeast Asia. Likewise, wines and olives grown in Europe and North Africa were shipped via Mexico to Manila.[20]

The city was captured by Great Britain in 1762 as part of the European Seven Years' War between Spain, France and Great Britain.[21] The city was then occpuied by the British for almost two years from 1762 to 1764 and remained the capital of the Philippines.[22] Eventually, the British withdrew in accordance with the 1763 Treaty of Paris. An unknown number of Indian soldiers known as sepoys, who came with the British, deserted and settled in nearby Cainta, Rizal, which explains the uniquely Indian features of generations of Cainta residents.[23][24]

The Chinese were then punished for supporting the British invasion, and the fortress city of Intramuros, initially populated by 1200 Spanish families and garrisoned by 400 Spanish troops,[25] kept its cannons pointed at Binondo, the world's oldest Chinatown.[26] The Mexican population was concentrated at the south part of Manila,[27][28] and also at Cavite, where ships from Spain's American colonies docked, and at Ermita, an area so named because of a Mexican hermit that lived there.[29]

After Mexico gained independence in 1821, Spain began to govern Manila directly.[30] Under direct Spanish rule, banking, industry and education flourished more than they had in the previous two centuries.[31] The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 facilitated direct trade and communications with Spain.

The city's growing wealth and education attracted indigenous people, Chinese, Indians, Latinos, and Europeans from the surrounding provinces[32] and facilitated the rise of an ilustrado class that espoused liberal ideas: the ideological foundations of the Philippine Revolution, which sought independence from Spain.

American period

After the 1898 Battle of Manila, Spain ceded Manila to the United States. The First Philippine Republic, based in nearby Bulacan, fought against the Americans for control of the city.[33] The Americans defeated the First Philippine Republic and captured President Emilio Aguinaldo, who declared allegiance to the United States on April 1, 1901.

Upon drafting a new charter for Manila in June 1901, the Americans made official what had long been tacit: that the city of Manila consisted not of Intramuros alone but also of the surrounding areas. The new charter proclaimed that Manila was composed of eleven municipal districts: presumably Binondo, Ermita, Intramuros, Malate, Paco, Pandacan, Sampaloc, San Miguel, Santa Ana, Santa Cruz and Tondo. In addition, the Catholic Church recognized five parishes—Gagalangin, Trozo, Balic-Balic, Santa Mesa and Singalong—as part of Manila. Later, two more would be added: Balut and San Andres.[34]

Under American control, a new, civilian-oriented Insular Government headed by Governor-General William Howard Taft invited city planner Daniel Burnham to adapt Manila to modern needs.[35] The Burnham Plan included the development of a road system, the use of waterways for transportation, and the beautification of Manila with waterfront improvements and construction of parks, parkways and buildings.[36][37]

The planned buildings included a government center occupying all of Wallace Field, which extends from Rizal Park to the present Taft Avenue. The Philippine Capitol was to rise at the Taft Avenue end of the field, facing toward the sea. Along with buildings for various government bureaus and departments, it would form a quadrangle with a lagoon in the center and a monument to José Rizal at the other end of the field. Of Burnham's proposed government center, only three units—the Legislative Building and the buildings of the Finance and Agricultural Departments—were completed when World War II erupted.

Japanese occupation and World War II

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, American soldiers were ordered to withdraw from Manila, and all military installations were removed on December 24, 1941. General Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an open city to prevent further death and destruction, but Japanese warplanes continued to bomb it. Manila was occupied by Japanese forces on January 2, 1942.

From February 3 to March 3, 1945, Manila was the site of the bloodiest battle in the Pacific theater of World War II. Some 100,000 civilians were killed in February.[38] At the end of the battle, Manila was recaptured by joint American and Philippine troops. It was the second most devastated city in the world, after Warsaw, during the Second World War. Almost all of the structures in the city, particularly in Intramuros, were destroyed.

Contemporary period

In 1948, President Elpidio Quirino moved the seat of government of the Philippines to Quezon City, a new capital in the suburbs and fields northeast of Manila, created in 1939 during the administration of President Manuel L. Quezon.[39] The move ended any implementation of the Burnham Plan's intent for the government centre to be at Luneta.

With the Visayan-born Arsenio Lacson as its first elected mayor in 1952 (all mayors were appointed before this), Manila underwent The Golden Age,[40] once again earning its status as the "Pearl of the Orient", a moniker it earned before the Second World War. After Lacson's term in the 1950s, Manila was led by Antonio Villegas for most of the 1960s. Ramon Bagatsing (an Indian-Filipino) was mayor for nearly the entire 1970s until the 1986 People Power Revolution. Mayors Lacson, Villegas, and Bagatsing are collectively known as the "Big Three of Manila" for their contribution to the development of the city and their lasting legacy in improving the quality of life and welfare of the people of Manila.

During the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, the region of Metro Manila was created as an integrated unit with the enactment of Presidential Decree No. 824 on November 7, 1975. The area encompassed four cities and thirteen adjoining towns, as a separate regional unit of government.[41] On the 405th anniversary of the city's foundation on June 24, 1976, Manila was reinstated by Marcos as the capital of the Philippines for its historical significance as the seat of government since the Spanish Period. Presidential Decree No. 940 states that Manila has always been to the Filipino people and in the eyes of the world, the premier city of the Philippines being the center of trade, commerce, education and culture.[42]

During the martial law era, Manila became a hot-bed of resistance activity as youth and student demonstrators repeatedly clashed with the police and military which were subservient to the Marcos regime. After decades of resistance, the non-violent People Power Revolution (predecessor to the peaceful-revolutions that toppled the iron-curtain in Europe), ousted the authoritarian Marcos from power.[43]

In 1992, Alfredo Lim was elected mayor, the first Chinese-Filipino to hold the office. He was known for his anti-crime crusades. Lim was succeeded by Lito Atienza, who served as his vice mayor. Atienza was known for his campaign (and city slogan) "Buhayin ang Maynila" (Revive Manila), which saw the establishment of several parks and the repair and rehabilitation of the city's deteriorating facilities. He was the city's mayor for 3 terms (9 years) before being termed out of office.

Lim once again ran for mayor and defeated Atienza's son Ali in the 2007 city election and immediately reversed all of Atienza's projects[44] claiming Atienza's projects made little contribution to the improvements of the city. The relationship of both parties turned bitter, with the two pitting again during the 2010 city elections in which Lim won against Atienza.

Lim was sued by councilor Dennis Alcoreza on 2008 over human rights,[45] charged with graft over the rehabilitation of public schools,[46] and was heavily criticized for his haphazard resolution of the Rizal Park hostage taking incident, one of the deadliest hostage crisis in the Philippines. Later on, Vice Mayor Isko Moreno and 28 city councilors filed another case against Lim in 2012, stating that Lim's statement in a meeting were "life-threatening" to them.[47] In the 2013 elections, former President Joseph Estrada defeated Lim in the mayoral race. During his term, Estrada has paid more than ₱5 billion in city debts and increased the city's revenues from ₱6.2 billion in 2012 to ₱14.6 billion by 2016, resulting in increased infrastructure spending and the betterment of the welfare of the people of Manila. In 2015, the city became the most competitive city in the Philippines, making the city the best place for doing business and for living in. However, despite these achievements, Estrada only narrowly won over Lim in their electoral rematch in 2016.[48]

Torre de Manila, an under-construction residential building by DMCI Homes, is controversial for ruining the sight line of Rizal Park and violating several building and zoning laws.[49] It is now known as the "national photobomber" or as "Terror de Manila". It drew flak after heritage preservation groups and citizens condemned it for destroying the historical monument’s view.[50]

Geography

Manila is situated on the eastern shore of Manila Bay, on the western edge of Luzon, 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) from mainland Asia.[51] One of Manila's greatest natural resources is the protected harbor upon which it sits, regarded as the finest in all of Asia.[52] The Pasig River flows through the middle of city.[3][4] The overall grade of the city's central, built-up areas, is relatively consistent with the natural flatness of its overall natural geography, generally exhibiting only slight differentiation otherwise.

In 2017, the City Government approved four reclamation projects: the New Manila Bay International Community (407.43 hectares), Solar City (148 hectares), the Manila Harbour Center expansion (50 hectares) and Horizon Manila (419 hectares). Projects such as these have been criticized by environmentalists and the Catholic Church, stating that these reclamation projects are not sustainable and would put communities at risk of flooding.[53][54] A fifth reclamation project is possible and when built, it will contain the in-city housing relocation projects.[55]

Almost all of Manila sits on top of centuries of prehistoric alluvial deposits built by the waters of the Pasig River and on some land reclaimed from Manila Bay. Manila's land has been altered substantially by human intervention, with considerable land reclamation along the waterfronts since the American colonial times. Some of the city's natural variations in topography have been evened out. As of 2013, Manila had a total area of 42.88 square kilometres (16.56 sq mi).[3][4]

Earthquakes

Swiss Re, the world’s second-largest reinsurer based in Zürich, Switzerland, places Manila as the second riskiest capital city to live in. The company cited dangers of earthquakes and flooding.[56] The seismically active Marikina Valley Fault System poses a threat to Manila and the surrounding regions.[57] Manila has endured several deadly earthquakes, notably in 1645 and in 1677 which destroyed the stone and brick medieval city.[58] The Earthquake Baroque style was used by architects during the Spanish colonial period in order to adapt to the frequent earthquakes.[59]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification system, Manila has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw). Together with the rest of the Philippines, Manila lies entirely within the tropics. Its proximity to the equator means that the temperature range is very small, rarely going below 20 °C (68 °F) or above 38 °C (100 °F). Temperature extremes have ranged from 14.5 °C (58.1 °F) on January 11, 1914,[60] to 38.6 °C (101.5 °F) on May 7, 1915.[61]

Humidity levels are usually very high all year round. Manila has a distinct dry season from December through May, and a relatively lengthy wet season that covers the remaining period with slightly cooler temperatures. In the wet season, it rarely rains all day, but rainfall is very heavy during short periods. Typhoons usually occur from June to September.[62]

| Climate data for Port Area, Manila | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.0 (84.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

32.9 (91.2) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

31.02 (87.83) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.9 (75) |

24.2 (75.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.1 (79) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25.39 (77.71) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.9 (75) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.97 (71.54) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 13.5 (0.531) |

7.3 (0.287) |

21.4 (0.843) |

18.7 (0.736) |

138.6 (5.457) |

283.8 (11.173) |

364.1 (14.335) |

476.3 (18.752) |

334.1 (13.154) |

200.5 (7.894) |

111.4 (4.386) |

56.0 (2.205) |

2,025.7 (79.753) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.10 mm) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 16 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 14 | 9 | 143 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 73 | 66 | 64 | 68 | 76 | 80 | 83 | 81 | 78 | 76 | 75 | 74.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 176.7 | 197.8 | 225.8 | 258.0 | 222.7 | 162.0 | 132.8 | 132.8 | 132.0 | 157.6 | 153.0 | 151.9 | 2,103.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 51 | 61 | 61 | 70 | 57 | 42 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 44 | 45 | 44 | 48 |

| Source #1: PAGASA[63] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Climatemps.com (sunshine)[64] | |||||||||||||

Environment

Due to industrial waste and automobiles, Manila suffers from air pollution,[65][66] affecting 98% of the population.[67] Annually, the air pollution causes more than 4,000 deaths.[68] Ermita is Manila's most air polluted district due to open dump sites and industrial waste.[69] According to a report in 2003, the Pasig River is one of the most polluted rivers in the world with 150 tons of domestic waste and 75 tons of industrial waste dumped daily.[70]

Annually, Manila is hit with 5 to 7 typhoons creating floods.[71] In 2009, Typhoon Ketsana struck the Philippines. In its aftermath, the lack of infrastructure led to one of the worst floodings in the Philippines and creating a significant amount of pollution.[72] Following the aftermath of Typhoon Ketsana, the city began to dredge its rivers and improve its drainage network. The Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission is in charge of cleaning up the Pasig River and tributaries for transportation, recreation and tourism purposes.[73] Rehabilitation efforts have resulted in the creation of parks along the riverside, along with stricter pollution controls.[74][75]

Cityscape

The city is made up of fourteen city districts, according to Republic Act No. 409—the Revised Charter of the City of Manila—the basis of which officially sets the present-day boundary of the city.[76] Two were later added, which are Santa Mesa (partitioned off from Sampaloc) and San Andres (partitioned off from Santa Ana).

Architecture

Manila is known for its eclectic mix of architecture that shows a wide range of styles spanning different historical and cultural periods. Architectural styles reflect American, Spanish, Chinese, and Malay influences.[77] Prominent Filipino architects such as Antonio Toledo, Felipe Roxas, Juan M. Arellano and Tomás Mapúa have designed significant buildings in Manila such as churches, government offices, theaters, mansions, schools and universities.

Manila is also famed for its Art Deco theaters. Some of these were designed by National Artists for Architecture such as Juan Nakpil and Pablo Antonio. Unfortunately most of these theater neglected, and some of it have been demolished. The historic Escolta Street in Binondo features many buildings of Neoclassical and Beaux-Arts architectural style, many of which were designed by prominent Filipino architects during the American Rule in the 1920s to the late 1930s. Many architects, artists, historians and heritage advocacy groups are pushing for the revival of Escolta Street, which was once the premier street of the Philippines.[78]

Almost all of Manila's prewar and Spanish colonial architecture were destroyed during its battle for liberation by the intensive bombardment of the United States Air Force during World War II. Reconstruction took place afterwards, replacing the destroyed historic Spanish-era buildings with modern ones, erasing much of the city's character. Some buildings destroyed by the war have been reconstructed, such as the Old Legislative Building (now the National Museum of Fine Arts), Ayuntamiento de Manila (now the Bureau of the Treasury) and the currently under construction San Ignacio Church and Convent (as the Museo de Intramuros). There are plans to rehabilitate and/or restore several neglected historic buildings and places such as Plaza Del Carmen, San Sebastian Church and the Manila Metropolitan Theater. Spanish-era shops and houses in the districts of Binondo, Quiapo, and San Nicolas are also planned to be restored, as a part of a movement to restore the city to its former glory and its beautiful prewar state.[79][80]

Since Manila is prone to earthquakes, the Spanish colonial architects invented the style called Earthquake Baroque which the churches and government buildings during the Spanish colonial period adopted.[59] As a result, succeeding earthquakes of the 18th and 19th centuries barely affected Manila, although it did periodically level the surrounding area. Modern buildings in and around Manila are designed or have been retrofitted to withstand an 8.2 magnitude quake in accordance to the country's building code.[81]

Demographics

| Population Census of Manila | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1903 | 219,928 | — |

| 1918 | 283,613 | +1.71% |

| 1939 | 623,492 | +3.82% |

| 1948 | 983,906 | +5.20% |

| 1960 | 1,138,611 | +1.22% |

| 1970 | 1,330,788 | +1.57% |

| 1975 | 1,479,116 | +2.14% |

| 1980 | 1,630,485 | +1.97% |

| 1990 | 1,601,234 | −0.18% |

| 1995 | 1,654,761 | +0.62% |

| 2000 | 1,581,082 | −0.97% |

| 2007 | 1,660,714 | +0.68% |

| 2010 | 1,652,171 | −0.19% |

| 2015 | 1,780,148 | +1.43% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[82][83][84][85] | ||

According to the 2015 census, the population of the city was 1,780,148, making it the second most populous city in the Philippines.[5]

Manila is the most densely populated city in the world, with 43,079 inhabitants per km2.[86] District 6 is listed as being the most dense with 68,266 inhabitants per km2, followed by District 1 with 64,936 and District 2 with 64,710, respectively. District 5 is the least densely populated area with 19,235.[87]

Manila's population density dwarfs that of Kolkata (27,774 inhabitants per km2), Mumbai (22,937 inhabitants per km2), Paris (20,164 inhabitants per km2), Dhaka (19,447 inhabitants per km2), Shanghai (16,364 inhabitants per km2, with its most dense district, Nanshi, having a density of 56,785 inhabitants per km2), and Tokyo (10,087 inhabitants per km2).[87]

Manila has been presumed to be the Philippines' largest city since the establishment of a permanent Spanish settlement with the city eventually becoming the political, commercial and ecclesiastical capital of the country.[88] Its population increased dramatically since the 1903 census as the population tended to move from rural areas to towns and cities. In the 1960 census, Manila became the first Philippine city to breach the one million mark (more than 5 times of its 1903 population). The city continued to grow until the population somehow "stabilized" at 1.6 million and experienced alternating increase and decrease starting the 1990 census year. This phenomenon may be attributed to the higher growth experience by suburbs and the already very high population density of city. As such, Manila exhibited a decreasing percentage share to the metropolitan population[89] from as high as 63% in the 1950s to 27.5%[90] in 1980 and then to 13.8% in 2015. The much larger Quezon City marginally surpassed the population of Manila in 1990 and by the 2015 census already has 1.1 million people more. Nationally, the population of Manila is expected to be overtaken by cities with larger territories such as Caloocan City and Davao City by 2020.[91]

The vernacular language is Filipino, based mostly on the Tagalog language of surrounding areas, and this Manila form of spoken Tagalog has essentially become the lingua franca of the Philippines, having spread throughout the archipelago through mass media and entertainment. English is the language most widely used in education, business, and heavily in everyday usage throughout Metro Manila and the Philippines itself.

A number of older residents can still speak basic Spanish, which used to be a mandatory subject in the curriculum of Philippine universities and colleges, and many children of Japanese Filipino, Korean Filipino, Indian Filipino, and other migrants or expatriates also speak their parents' languages at home, aside from English and/or Filipino for everyday use. A variant of Southern Min, Hokkien (locally known as Lan'nang-oe) is mainly spoken by the city's Chinese-Filipino community.

Economy

Manila is a major center for commerce, banking and finance, retailing, transportation, tourism, real estate, new media as well as traditional media, advertising, legal services, accounting, insurance, theater, fashion, and the arts in the Philippines. Around 60,000 establishments operates in the city.[92]

The National Competitiveness Council of the Philippines which annually publishes the Cities and Municipalities Competitiveness Index (CMCI), ranks the cities, municipalities and provinces of the country according to their economic dynamism, government efficiency and infrastructure. According to the 2016 CMCI, Manila was the second most competitive city in the Philippines.[93] Manila placed third in the Highly Urbanized City (HUC) category.[94] Manila held the title country's most competitive city in 2015, and since then has been making it to the top 3, assuring that the city is consistently one of the best place to live in and do business.[95] Lars Wittig, the country manager of Regus Philippines, hailed Manila as the third best city in the country to launch a start-up business.[96]

The Port of Manila is the largest seaport in the Philippines, making it the premier international shipping gateway to the country. The Philippine Ports Authority is the government agency responsible to oversee the operation and management of the ports. The International Container Terminal Services Inc. cited by the Asian Development Bank as one of the top five major maritime terminal operators in the world[97][98] has its headquarters and main operations on the ports of Manila. Another port operator, the Asian Terminal Incorporated, has its corporate office and main operations in the Manila South Harbor and its container depository located in Santa Mesa.

Binondo, the oldest and one of the largest Chinatowns in the world, was the center of commerce and business activities in the city. Numerous residential and office skyscrapers are found within its medieval streets. Plans to make the Chinatown area into a business process outsourcing (BPO) hub progresses and is aggressively pursued by the city government of Manila. 30 buildings are already identified to be converted into BPO offices. These buildings are mostly located along the Escolta Street of Binondo, which are all unoccupied and can be converted into offices.[99]

Divisoria in Tondo is known as the "shopping mecca of the Philippines". Numerous shopping malls are located in this place, which sells products and goods at bargain price. Small vendors occupy several roads that causes pedestrian and vehicular traffic. A famous landmark in Divisoria is the Tutuban Center, a large shopping mall that is a part of the Philippine National Railways' Main Station. It attracts 1 million people every month, but is expected to add another 400,000 people when the LRT Line 2 West Extension is constructed, which is set to make it as Manila's busiest transfer station.[100]

Diverse manufacturers within the city produce industrial-related products such as chemicals, textiles, clothing, and electronic goods. Food and beverages and tobacco products also produced. Local entrepreneurs continue to process primary commodities for export, including rope, plywood, refined sugar, copra, and coconut oil. The food-processing industry is one of the most stable major manufacturing sector in the city.

The Pandacan Oil Depot houses the storage facilities and distribution terminals of the three major players in the country's petroleum industry, namely Caltex Philippines, Pilipinas Shell and Petron Corporation. The oil depot has been a subject of various concerns, including its environmental and health impact to the residents of Manila. The Supreme Court has ordered that the oil depot to be relocated outside the city by July 2015,[101][102] but it failed to meet this deadline. It is currently being demolished which is expected to be finished before the year 2016 ends, and plans have been set up to turn this 33 hectare facility into a transport hub or even a food park.

Manila is a major publishing center in the Philippines.[103] Manila Bulletin, the Philippines' largest broadsheet newspaper by circulation, is headquartered in Intramuros.[104] Other major publishing companies in the country like The Manila Times, The Philippine Star and Manila Standard Today are headquartered in the Port Area. The Chinese Commercial News, the Philippines' oldest existing Chinese-language newspaper, and the country's third-oldest existing newspaper[105] is headquartered in Binondo.

Manila serves as the headquarters of the Central Bank of the Philippines which is located along Roxas Boulevard.[106] Some universal banks in the Philippines that has its headquarters in the city are the Landbank of the Philippines and Philippine Trust Company. Philam Life Insurance Company, currently the largest life insurance company in the Philippines in terms of assets, net worth, investment and paid-up capital,[107][108][109] has its headquarters along United Nations Avenue in Ermita. Unilever Philippines has its corporate office along United Nations Avenue in Paco.[110] Toyota, a company listed in the Forbes Global 2000, also has its regional office along UN Avenue.

Tourism

Manila welcomes over 1 million tourists each year.[103] Major destinations include the historic Walled City of Intramuros, the Cultural Center of the Philippines Complex,[note 1] Manila Ocean Park, Binondo (Chinatown), Ermita, Malate, Manila Zoo, the National Museum Complex and Rizal Park. The Walled City of Intramuros and Rizal Park were designated as flagship destination and as a tourism enterprise zone in the Tourism Act of 2009.[111]

Rizal Park, also known as Luneta Park, is the national park and the largest urban park in Asia[112] with an area of 58 hectares (140 acres),[113] The park was constructed as an honor and dedication to the country's national hero José Rizal, who was executed by the Spaniards on charges of subversion. The flagpole west of the Rizal Monument is the Kilometer Zero marker for distances to the rest of the country. The park was managed by the National Parks and Development Committee.

The 0.67 square kilometers (0.26 sq mi) Walled City of Intramuros is the historic center of Manila. It is administered by the Intramuros Administration, an attached agency of the Department of Tourism. It contains the famed Manila Cathedral and the 18th Century San Agustin Church, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Kalesa is a popular mode of transportation for tourists in Intramuros and nearby places including Binondo, Ermita and Rizal Park.[114]

The Department of Tourism designates Manila as the pioneer of medical tourism, expecting it to generate $1 billion in revenue annually.[115] However, lack of progressive health system, inadequate infrastructure and the unstable political environment are seen as hindrances for its growth.[116]

Shopping

Manila is regarded as one of the best shopping destinations in Asia.[117][118] Major shopping malls, department stores, markets, supermarkets and bazaars thrives within the city.

Robinsons Place Manila is the largest shopping mall in the city.[119] The mall was the second and the largest Robinsons Malls built. SM Supermall operates two shopping malls in the city which are the SM City Manila and SM City San Lazaro. SM City Manila is located on the former grounds of YMCA Manila beside the Manila City Hall in Ermita, while SM City San Lazaro is built on the site of the former San Lazaro Hippodrome in Sta. Cruz. The building of the former Manila Royal Hotel in Quiapo, which is famed for its revolving restaurant atop, is now the SM Clearance Center that was established in 1972.[120] The site of the first SM Store is located at Carlos Palanca Sr. (formerly Echague) Street in San Miguel.

Quiapo is referred to as the "Old Downtown", where tiangges, markets, boutique shops, music and electronics stores are common. C.M. Recto Avenue is where lots of department stores are located. One of Recto Avenue's famous destinations is Divisoria, home to numerous shopping malls in the city, including the famed Tutuban Center and the Lucky Chinatown Mall. It is also dubbed as the shopping mecca of the Philippines where everything is sold at bargain price. Binondo, the oldest Chinatown in the world,[26] is the city's center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants with a wide variety of Chinese and Filipino shops and restaurants.

Culture and contemporary life

Religion

Christianity

As a result of Spanish cultural influence, Manila is a predominantly Christian city. As of 2010, Roman Catholics were 83.5% of the population, followed by adherents of the Philippine Independent Church (2.4%); Iglesia ni Cristo (1.9%); various Protestant churches (1.8%); and Buddhists (1.1%). Members of Islam and other religions make up the remaining 10.4% of the city's population.[121]

Manila is the site of prominent Catholic churches and institutions. There are 113 Catholic churches within the city limits; 63 are considered as major shrines, basilicas, or a cathedral.[122] The Manila Cathedral is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila and the oldest established church in the country.[123] Aside from the Manila Cathedral, there are also three other basilicas in the city: Quiapo Church, Binondo Church, and the Minor Basilica of San Sebastián. The San Agustín Church in Intramuros is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is one of the two fully air-conditioned Catholic churches in the city. Manila also has other parishes located throughout the city, with some of them dating back to the Spanish Colonial Period when the city serves as the base for numerous Catholic missions both within the Philippines and to Asia beyond.

Several Mainline Protestant denominations are headquartered in the city. St. Stephen's Parish pro-cathedral in the Sta. Cruz district is the see of the Episcopal Church in the Philippines' Diocese of Central Philippines, while align Taft Avenue are the main cathedral and central offices of the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (also called the Aglipayan Church, a national church that was a product of the Philippine Revolution). Other faiths like The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) has several churches in the city.

The indigenous Iglesia ni Cristo has several locales (akin to parishes) in the city, including its very first chapel (now a museum) in Punta, Sta. Ana. Evangelical, Pentecostal and Seventh-day Adventist denominations also thrive within the city. The headquarters of the Philippine Bible Society is in Manila. Also, the main campus of the Cathedral of Praise is located along Taft Avenue. Jesus Is Lord Church also has several branches and campuses in Manila, and celebrates its anniversary yearly at the Burnham Green and Quirino Grandstand in Rizal Park.

Manila Cathedral is the seat of Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila

Manila Cathedral is the seat of Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila_Manila%2C_Filipinas..jpg)

- The Binondo Church

Quiapo Church is the home to the iconic Black Nazarene which celebrates its feasts every January 9.

Quiapo Church is the home to the iconic Black Nazarene which celebrates its feasts every January 9.

Other faiths

The city also hosts other religions. There are many Buddhist and Taoist temples serving the Chinese Filipino community. Quiapo is home to a sizable Muslim population which worships at Masjid Al-Dahab. Members of the Indian expatriate population have the option of worshiping at the large Hindu temple in the city, or at the Sikh gurdwara along United Nations Avenue. The National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the Philippines, the governing body of the Filipino Bahá'í community, is headquartered near Manila's eastern border with Makati.

Festivities and holidays

Manila celebrates civic and national holidays. Manila Day, which celebrates the city's founding on June 24, 1571, was first proclaimed by Herminio A. Astorga (then Vice Mayor of Manila) on June 24, 1962 and has been annually commemorated, under the patronage of John the Baptist. Locally, each of the city's barangays also have their own festivities guided by their own patron saint. The city is also the host to the Feast of the Black Nazarene, held every January 9, which draws millions of Catholic devotees. Other religious feasts held in Manila are the Feast of Santo Niño in Tondo and Pandacan held on the third Sunday of January and the Feast of the Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados de Manila (Our Lady of the Abandoned), the patron saint of Santa Ana and held every May 12. Non-religious holidays include the New Year's Day, National Heroes' Day, Bonifacio Day and Rizal Day.

Museums

As the cultural center of the Philippines, Manila is the home to a number of museums. The National Museum of the Philippines operates a chain of museums in Rizal Park, such as the National Museum of Fine Arts, the National Museum of Anthropology and the National Museum of Natural History. Museums established by educational institutions include the Mabini Shrine, the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, UST Museum of Arts and Sciences, and the UP Museum of a History of Ideas.

Bahay Tsinoy, one of Manila's most prominent museums, documents the Chinese lives and contributions in the history of the Philippines. The Intramuros Light and Sound Museum chronicles the Filipinos desire for freedom during the revolution under Rizal's leadership and other revolutionary leaders. The Metropolitan Museum of Manila exhibits the Filipino arts and culture.

Other museums in the city are the Museum of Manila, the city-owned museum that exhibits the city's culture and history, Museo Pambata, a children's museum, the Museum of Philippine Political History, which exhibits notable political events in the country, the Parish of the Our Lady of the Abandoned and the San Agustin Church Museum, which houses religious artifacts, and Plaza San Luis, a public museum.

Sports

Sports in Manila have a long and distinguished history. The city's, and in general the country's main sport is basketball, and most barangays have a basketball court or at least a makeshift basketball court, with court markings drawn on the streets. Larger barangays have covered courts where inter-barangay leagues are held every summer (April to May). Manila has many sports venues, such as the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex and San Andres Gym, the home of the now defunct Manila Metrostars.[125] The Rizal Memorial Sports Complex houses the Rizal Memorial Track and Football Stadium, the Baseball Stadium, Tennis Courts, Memorial Coliseum and the Ninoy Aquino Stadium (the latter two are indoor arenas). The Rizal complex had hosted several multi-sport events, such as the 1954 Asian Games and the 1934 Far Eastern Games. Whenever the country hosts the Southeast Asian Games, most of the events are held at the complex, but in the 2005 Games, most events were held elsewhere. The 1960 ABC Championship and the 1973 ABC Championship, forerunners of the FIBA Asia Championship, was hosted by the complex, with the national basketball team winning on both tournaments. The 1978 FIBA World Championship was held at the complex although the latter stages were held in the Araneta Coliseum in Quezon City, Southeast Asia's largest indoor arena at that time.

Manila also hosts several well-known sports facilities such as the Enrique M. Razon Sports Center and the University of Santo Tomas Sports Complex, both of which are private venues owned by a university; collegiate sports are also held, with the University Athletic Association of the Philippines and the National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball games held at Rizal Memorial Coliseum and Ninoy Aquino Stadium, although basketball events had transferred to San Juan's Filoil Flying V Arena and the Araneta Coliseum in Quezon City. Other collegiate sports are still held at the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex. Professional basketball also used to play at the city, but the Philippine Basketball Association now holds their games at Araneta Coliseum and Cuneta Astrodome at Pasay; the now defunct Philippine Basketball League played some of their games at the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex.

The Manila Storm are the city's rugby league team training at Rizal Park (Luneta Park) and playing their matches at Southern Plains Field, Calamba, Laguna. Previously a widely played sport in the city, Manila is now the home of the only sizable baseball stadium in the country, at the Rizal Memorial Baseball Stadium. The stadium hosts games of Baseball Philippines; Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth were the first players to score a home run at the stadium at their tour of the country on December 2, 1934.[126] Another popular sport in the city are cue sports, and billiard halls are a feature in most barangays. The 2010 World Cup of Pool was held at Robinsons Place Manila.[127]

The Rizal Memorial Track and Football Stadium hosted the first FIFA World Cup qualifier in decades when the Philippines hosted Sri Lanka in July 2011. The stadium, which was previously unfit for international matches, had undergone a major renovation program before the match.[128] The Football Stadium now regularly hosts matches of the United Football League. The stadium also hosted its first rugby test when it hosted the 2012 Asian Five Nations Division I tournaments.[129]

Law and government

.jpg)

Manila—officially known as the City of Manila—is the national capital of the Philippines and is classified as a Special City (according to its income)[130][131] and a Highly Urbanized City (HUC). The mayor is the chief executive, and is assisted by the vice mayor, the 36-member City Council, six Congressmen, the President of the Association of Barangay Captains, and the President of the Sangguniang Kabataan. The members of the City Council are elected as representatives of specific congressional districts within the city. The city, however, have no control over Intramuros and the Manila North Harbor. The historic Walled City is administered by the Intramuros Administration, while the Manila North Harbor is managed by the Philippine Ports Authority. Both are national government agencies. The barangays that have jurisdictions over these places only oversee the welfare of the city's constituents and cannot exercise their executive powers.

The current mayor is Joseph Estrada, who served as the President of the Philippines from 1998 to 2001. He is currently on his second term in serving as the city mayor. The current vice mayor is Dr. Maria Shielah "Honey" Lacuna-Pangan, daughter of former Manila Vice Mayor Danny Lacuna. The mayor and the vice mayor are term-limited by up to 3 terms, with each term lasting for 3 years.

Manila, being the seat of political power of the Philippines, has several national government offices headquartered at the city. Planning for the development for being the center of government started during the early years of American colonization when they envisioned a well-designed city outside the walls of Intramuros. The strategic location chosen was Bagumbayan, a former town which is now the Rizal Park to become the center of government and a design commission was given to Daniel Burnham to create a master plan for the city patterned after Washington, D.C. These improvements were eventually abandoned under the Commonwealth Government of Manuel L. Quezon.

A new government center was to be built on the hills northeast of Manila, or what is now Quezon City. Several government agencies have set up their headquarters in Quezon City but several key government offices still reside in Manila. However, many of the plans were substantially altered after the devastation of Manila during World War II and by subsequent administrations.

The city, as the capital, still hosts the Office of the President, as well as the president's official residence. Aside from these, important government agencies and institutions such as the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeals, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, the Departments of Budget and Management, Finance, Health, Justice, Labor and Employment and Public Works and Highways still call the city home. Manila also hosts important national institutions such as the National Library, National Archives, National Museum and the Philippine General Hospital.

Congress previously held office at the Old Congress Building. In 1972, due to declaration of martial law, Congress was dissolved; its successor, the unicameral Batasang Pambansa, held office at the new Batasang Pambansa Complex. When a new constitution restored the bicameral Congress, the House of Representatives stayed at the Batasang Pambansa Complex, while the Senate remained at the Old Congress Building. In May 1997, the Senate transferred to a new building it shares with the Government Service Insurance System at reclaimed land at Pasay. The Supreme Court will also transfer to its new campus at Bonifacio Global City, Taguig in 2019.[132]

Finance

In the 2015 Annual Audit Report by the Commission on Audit on the City of Manila, the city's total income was ₱12,589,845,794. The city increased its revenue collection by 20.80% or 1.94 billion pesos higher than that of 2014.[133] The city's asset was worth ₱18.6 billion in 2013.[134] Its local income was ₱5.41 billion and its national government allocation was ₱1.74 billion, having an annual regular income (ARI) of ₱7.15 billion.[135] Manila's net income was ₱3.54 billion in 2014.[136] The City of Manila has the highest budget allocation to healthcare among all the cities and municipalities in the Philippines. It was also one of the cities with the highest tax and internal revenue.[137] Tax revenue accounts for 46% of the city's income in 2012.[138] Manila employs 14,586 personnel by the end of 2015.[133]

Barangays and Districts

Manila is made up of 896 barangays,[139] which are grouped into 100 Zones for statistical convenience. Manila has the most number of barangays in the Philippines.[140] Attempts at reducing its number have not prospered despite local legislation—Ordinance 7907, passed on 23 April 1996—reducing the number from 897 to 150 by merging existing barangays, because of the failure to hold a plebiscite.[141]

- The 1st District (2015 population: 415,906) covers the western part of Tondo and is the most densely populated Congressional District. It is the home to one of the biggest urban poor communities. The Smokey Mountain in Balut Island is once known as the largest landfill where thousands of impoverished people lives in the slums. After the closure of the landfill in 1995, mid-rise housing buildings were built in place. This district also contains the Manila North Harbour Centre, the Manila North Harbor, and the Manila International Container Terminal of the Port of Manila.

- The 2nd District (2015 population: 215,457) covers the eastern part of Tondo known as Gagalangin. It contains Divisoria, a popular shopping place in the Philippines and the site of the Main Terminal Station of the Philippine National Railways.

- The 3rd District (2015 population: 197,242) covers Binondo, Quiapo, San Nicolas and Santa Cruz.

- The 4th District (2015 population: 265,046) covers Sampaloc and some parts of Santa Mesa. It contains the University of Santo Tomas, the oldest existing university in Asia.

- The 5th District (2015 population: 366,714) covers Ermita, Malate, Paco Port Area, Intramuros, San Andres Bukid, and a portion of Santa Ana.

- The 6th District (2007 population: 295,245) covers Pandacan, San Miguel, Santa Ana, Santa Mesa and a portion of Paco.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Infrastructure

Utilities

Water and electricity

Water services used to be provided by the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System, which served 30% of the city with most other sewage being directly dumped into storm drains, septic tanks, or open canals.[142] MWSS was privatized in 1997, which split the water concession into the east and west zones. The Maynilad Water Services took over the west zone of which Manila is a part. It now provides the supply and delivery of potable water and sewerage system in Manila,[143] but it does not provide service to the southeastern part of the city which belongs to the east zone that is served by Manila Water. Electric services are provided by Meralco, the sole electric power distributor in Metro Manila.

Transportation

.jpg)

One of the more famous modes of transportation in Manila is the jeepney. Patterned after U.S. Army jeeps, these have been in use since the years immediately following World War II.[144] The Tamaraw FX, the third generation Toyota Kijang, which competed directly with jeepneys and followed fixed routes for a set price, once plied the streets of Manila. All types of public road transport plying Manila are privately owned and operated under government franchise.

On a for-hire basis, the city is served by numerous taxicabs, "tricycles" (motorcycles with sidecars, the Philippine version of the auto rickshaw), and "trisikads" or "sikads", which are also known as "kuligligs" (bicycles with a sidecars, the Philippine version of pedicabs). In some areas, especially in Divisoria, motorized pedicabs are popular. Spanish-era horse-drawn calesas are still a popular tourist attraction and mode of transportation in the streets of Binondo and Intramuros. By October 2016, the city will phase out all gasoline-run tricycles and pedicabs and replace them with electric tricycles (e-trikes). The city plans to distribute 10,000 e-trikes to qualified tricycle drivers from the city.[145][146]

The city is serviced by the LRT Line 1 and Line 2, which form the Manila Light Rail Transit System. Development of the railway system began in the 1970s under the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, when Line 1 was built, making it the first light rail transport in Southeast Asia. These systems are currently undergoing a multibillion-dollar expansion.[147] Line 1 runs along the length of Taft Avenue (R-2) and Rizal Avenue (R-9), and Line 2 runs along Claro M. Recto Avenue (C-1) and Ramon Magsaysay Boulevard (R-6) from Santa Cruz, through Quezon City, up to Masinag in Antipolo, Rizal.

The main terminal of the Philippine National Railways lies within the city. One commuter railway within Metro Manila is in operation. The line runs in a general north-south direction from Tutuban (Tondo) toward Laguna. The Port of Manila, located in the vicinity of Manila Bay, is the chief seaport of the Philippines. The Pasig River Ferry Service which runs on the Pasig River is another form of transportation. The city is also served by the Ninoy Aquino International Airport and Clark International Airport.

In 2006, Forbes magazine ranked Manila the world's most congested city. According to Waze's 2015 "Global Driver Satisfaction Index", Manila is the town with the worst traffic worldwide.[148] Manila is notorious for its frequent traffic jams and high densities.[149] The government has undertaken several projects to alleviate the traffic in the city. Some of the projects include: the construction of a new viaduct or underpass at the intersection of España Boulevard and Lacson Avenue,[150] the construction of the Metro Manila Skyway Stage 3, the proposed LRT Line 2 West Extension Project from Recto Avenue to Tondo or the Port Area,[151] and the expansion and widening of several national and local roads. However, such projects have yet to make any meaningful impact, and the traffic jams and congestion continue unabated.[152]

The Metro Manila Dream Plan, formulated in the mid-2010s seeks to address these problems. It consists of a list of short term priority projects and medium to long term infrastructure projects that will last up to 2030.[153][154]

Healthcare

The Manila Health Department is responsible for the planning and implementation of the health care programs provided by the city government. It operates 59 health centers and six city-run hospitals, which are free of charge for the city's constituents. The six public city-run hospitals are the Ospital ng Maynila Medical Center, Ospital ng Sampaloc, Gat Andres Bonifacio Memorial Medical Center, Ospital ng Tondo, Sta. Ana Hospital, and Justice Jose Abad Santos General Hospital.[155] Manila is also the site of the Philippine General Hospital, the tertiary state-owned hospital administered and operated by the University of the Philippines Manila. The city is also planning to put up an education, research and hospital facility for cleft-palate patients.[156][157]

Manila's healthcare is also provided by private corporations. Private hospitals that operates in the city are the Manila Doctors Hospital, Chinese General Hospital and Medical Center, Dr. José R. Reyes Memorial Medical Center, Metropolitan Medical Center, Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, and the University of Santo Tomas Hospital.

The Department of Health has its main office in Manila. The national health department also operates the San Lazaro Hospital, a special referral tertiary hospital. Manila is also the home to the headquarters of the World Health Organization's Regional Office for the Western Pacific and Country Office for the Philippines.

The city has free immunization programs for children, specifically targeted against the seven major diseases – smallpox, diphtheria, tetanus, yellow fever, whooping cough, polio, and measles. As of 2016, a total of 31,115 children age one and below has been “fully immunized”.[158] The Manila Dialysis Center that provides free services for the poor has been cited by the United Nations Committee on Innovation, Competitiveness and Public-Private Partnerships as a model for public-private partnership (PPP) projects.[159][160]

Education

The center of education since the colonial period, Manila — particularly Intramuros — is home to several Philippine universities and colleges as well as its oldest ones. It served as the home of the University of Santo Tomas (1611), Colegio de San Juan de Letran (1620), Ateneo de Manila University (1859), Lyceum of the Philippines University and the Mapua Institute of Technology. Only Colegio de San Juan de Letran (1620) remains at Intramuros; the University of Santo Tomas transferred to a new campus at Sampaloc in 1927, and Ateneo left Intramuros for Loyola Heights, Quezon City (while still retaining "de Manila" in its name) in 1952.

The University of the City of Manila (Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila) located at Intramuros, and Universidad de Manila located just outside the walled city, are both owned and operated by the Manila city government. The national government controls the University of the Philippines Manila, the oldest of the University of the Philippines constituent universities and the center of health sciences education in the country.[161] The city is also the site of the main campus of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines, the largest university in the country in terms of student population.[162]

The University Belt refers to the area where there is a high concentration or a cluster of colleges and universities in the city and it is commonly understood as the one where the San Miguel, Quiapo and Sampaloc districts meet. Generally, it includes the western end of España Boulevard, Nicanor Reyes St. (formerly Morayta St.), the eastern end of Claro M. Recto Avenue (formerly Azcarraga), Legarda Avenue, Mendiola Street, and the different side streets. Each of the colleges and universities found here are at a short walking distance of each other. Another cluster of colleges lies along the southern bank of the Pasig River, mostly at the Intramuros and Ermita districts, and still a smaller cluster is found at the southernmost part of Malate near the border with Pasay such as the private co-educational institution of De La Salle University, the largest of all De La Salle University System of schools.

The Division of the City Schools of Manila, a branch of the Department of Education, refers to the city's three-tier public education system. It governs the 71 public elementary schools, 32 public high schools.[163]

The city also contains the Manila Science High School, the pilot science high school of the Philippines; the National Museum, where the Spoliarium of Juan Luna is housed; the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, a museum of modern and contemporary visual arts; the Museo Pambata, the Children's Museum, a place of hands-on discovery and fun learning; and, the National Library, the repository of the country's printed and recorded cultural heritage and other literary and information resources.

Sister cities

Asia

-

Astana, Kazakhstan[164]

Astana, Kazakhstan[164] -

Bangkok, Thailand[165]

Bangkok, Thailand[165] -

Beijing, China[166][167]

Beijing, China[166][167] -

Dili, East Timor[168]

Dili, East Timor[168] -

Guangzhou, China[167]

Guangzhou, China[167] -

Haifa, Israel[169]

Haifa, Israel[169] -

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam[170]

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam[170] -

Incheon, South Korea[171]

Incheon, South Korea[171] -

Jakarta, Indonesia[172]

Jakarta, Indonesia[172] -

Nantan, Kyoto, Japan[173]

Nantan, Kyoto, Japan[173] -

Osaka, Japan (Business Partner)[174]

Osaka, Japan (Business Partner)[174] -

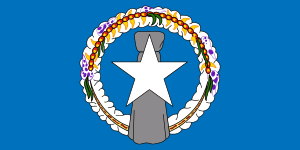

Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands[175]

Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands[175] -

Shanghai, China[176]

Shanghai, China[176] -

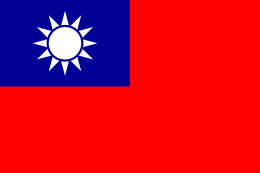

Taipei, Taiwan[177]

Taipei, Taiwan[177] -

Takatsuki, Osaka, Japan[178][179]

Takatsuki, Osaka, Japan[178][179] -

Yokohama, Japan[179][180]

Yokohama, Japan[179][180]

Europe

Americas

-

Acapulco, Mexico[183]

Acapulco, Mexico[183] -

Cartagena, Colombia[164]

Cartagena, Colombia[164] -

Havana, Cuba[164]

Havana, Cuba[164] -

Honolulu, Hawaii, United States[184][185]

Honolulu, Hawaii, United States[184][185] -

Lima, Peru[164]

Lima, Peru[164] -

Maui County, Hawaii, United States[185]

Maui County, Hawaii, United States[185] -

Mexico City, Mexico

Mexico City, Mexico -

Montreal, Quebec, Canada[186]

Montreal, Quebec, Canada[186] -

New York City, New York, United States (Global Partner)[187]

New York City, New York, United States (Global Partner)[187] -

Sacramento, California, United States[185]

Sacramento, California, United States[185] -

San Francisco, California, United States[185]

San Francisco, California, United States[185] -

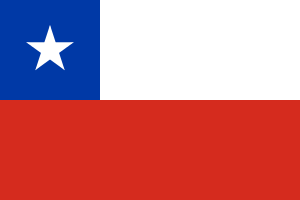

Santiago, Chile[164]

Santiago, Chile[164] -

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada[188]

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada[188]

See also

- Cities of the Philippines

- Greater Manila Area

- Imperial Manila

- Kingdom of Maynila

- List of cities in the Philippines

- Mega Manila

- Remarkable people from Manila

- SM Mall of Asia

Notes

References

- ↑ "'PEARL OF ORIENT' STRIPPED OF FOOD; Manila, Before Pearl Harbor, Had Been Prosperous—Its Harbor One, of Best Focus for Two Attacks Osmeña Succeeded Quezon". New York Times. 5 February 1945. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

Manila, modernized and elevated to the status of a metropolis by American engineering skill, was before Pearl Harbor a city of 623,000 population, contained in an area of fourteen square miles.

- ↑ "Cities". Quezon City, Philippines: Department of the Interior and Local Government. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "An Update on the Earthquake Hazards and Risk Assessment of Greater Metropolitan Manila Area" (PDF). Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. November 14, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Enhancing Risk Analysis Capacities for Flood, Tropical Cyclone Severe Wind and Earthquake for the Greater Metro Manila Area Component 5 – Earthquake Risk Analysis" (PDF). Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology and Geoscience Australia. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ "Demographia World Urban Areas PDF (March 2013)" (PDF). Demographia. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ This is the original Spanish, even used by José Rizal in El filibusterismo.

- ↑ "Annual Audit Report: City of Manila". 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ "GaWC – The World According to GaWC 2016". www.lboro.ac.uk. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ "Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population". Philippine Statistics Authority. May 19, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Global Metro Monitor". Brookings Institution. January 22, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ↑ "GRDP Tables 2015 (as of July 2016)". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ↑ "The Folklore on How Manila Got Its Name". Philippines Insider. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ↑ E.M. Pospelov, Geograficheskie nazvanie mira (Географические название мира) (Moscow 1998).

- ↑ Mijares, Armand Salvador B. (2006). .The Early Austronesian Migration To Luzon: Perspectives From The Peñablanca Cave Sites Archived July 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 26: 72–78.

- 1 2 3 Gerini, G. E. (1905). "The Nagarakretagama List of Countries on the Indo-Chinese Mainland (Circâ 1380 A.D.)". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (July 1905): 485–511. JSTOR 25210168.

- ↑ "Pusat Sejarah Brunei" (in Malay). Government of Brunei Darussalam. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 22

- ↑ Wright, Hamilton M. (1907). "A Handbook of the Philippines", p. 143. A.C. McClurcg & Co., Chicago.

- ↑ Kane, Herb Kawainui (1996). "The Manila Galleons". In Bob Dye. Hawaiʻ Chronicles: Island History from the Pages of Honolulu Magazine. I. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 25–32. ISBN 0-8248-1829-6.

- ↑ "Manila (Philippines)". Britannica. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ Backhouse, Thomas (1765). The Secretary at War to Mr. Secretary Conway. London: British Library. pp. v. 40.

- ↑ Fish 2003, p. 158

- ↑ "Wars and Battles: Treaty of Paris (1763)". www.u-s-history.com.

- ↑ Barrows, David (2014). "A History of the Philippines". Guttenburg Free Online E-books. 1: 179.

Within the walls, there were some six hundred houses of a private nature, most of them built of stone and tile, and an equal number outside in the suburbs, or "arrabales," all occupied by Spaniards ("todos son vivienda y poblacion de los Españoles"). This gives some twelve hundred Spanish families or establishments, exclusive of the religious, who in Manila numbered at least one hundred and fifty, the garrison, at certain times, about four hundred trained Spanish soldiers who had seen service in Holland and the Low Countries, and the official classes.

- 1 2 Raitisoja, Geni " Chinatown Manila: Oldest in the world", Tradio86.com, July 8, 2006, accessed March 19, 2011.

- ↑ "In 1637 the military force maintained in the islands consisted of one thousand seven hundred and two Spaniards and one hundred and forty Indians." ~Memorial de D. Juan Grau y Monfalcon, Procurador General de las Islas Filipinas, Docs. Inéditos del Archivo de Indias, vi, p. 425. "In 1787 the garrison at Manila consisted of one regiment of Mexicans comprising one thousand three hundred men, two artillery companies of eighty men each, three cavalry companies of fifty men each." La Pérouse, ii, p. 368.

- ↑ Barrows, David (2014). "A History of the Philippines". Guttenburg Free Online E-books. 1: 229.

Reforms under General Arandía.—The demoralization and misery with which Obando's rule closed were relieved somewhat by the capable government of Arandía, who succeeded him. Arandía was one of the few men of talent, energy, and integrity who stood at the head of affairs in these islands during two centuries. He reformed the greatly disorganized military force, establishing what was known as the "Regiment of the King," made up very largely of Mexican soldiers. He also formed a corps of artillerists composed of Filipinos. These were regular troops, who received from Arandía sufficient pay to enable them to live decently and like an army.

- ↑ "Living in the Philippines: Living, Retiring, Travelling and Doing Business".

- ↑ Fundación Santa María (Madrid) 1994, p. 508

- ↑ John Bowring, "Travels in the Philippines", p. 18, London, 1875

- ↑ Olsen, Rosalinda N. "Semantics of Colonization and Revolution". www.bulatlat.com. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ↑ The text of the amended version published by General Otis is quoted in its entirety in José Roca de Togores y Saravia; Remigio Garcia; National Historical Institute (Philippines) (2003), Blockade and siege of Manila, National Historical Institute, pp. 148–150, ISBN 978-971-538-167-3

See also s:Letter from E.S. Otis to the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands, January 4, 1899. - ↑ Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila My Manila. Vera-Reyes, Inc. p. 137, 178.

- ↑ Moore 1921, p. 162.

- ↑ Moore 1921, p. 162B.

- ↑ Moore 1921, p. 180.

- ↑ White, Matthew. "Death Tolls for the Man-made Megadeaths of the 20th Century". Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ "Milestone in History". Quezon City Official Website. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Hancock 2000, p. 16

- ↑ "Presidential Decree No. 824 November 7, 1975". The LawPhil Project. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Presidential Decree No. 940 June 24, 1976". Chan C. Robles Virtual Law Library. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Edsa people Power 1 Philippines". Angela Stuart-Santiago. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ↑ Mundo, Sheryl (December 1, 2009). "It's Atienza vs. Lim Part 2 in Manila". Manila: ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Archived from the original on December 3, 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

Environment Secretary Jose 'Lito' Atienza will get to tangle again with incumbent Manila Alfredo Lim in the coming 2010 elections.

- ↑ Legaspi, Amita (July 17, 2008). "Councilor files raps vs Lim, Manila execs before CHR". GMA News. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Mayor Lim charged anew with graft over rehabilitation of public schools". The Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "Isko Moreno, 28 councilors file complaint vs Lim". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ Lopez, Tony (June 10, 2016). "Erap's hairline victory". The Standard Philippines. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Ranada, Pia (August 4, 2014). "Pia Cayetano to look into Torre de Manila violations". Rappler. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ↑ Dario, Dethan (April 28, 2017). "Timeline: Tracking the Torre De Manila case". The Philippine Star. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Geography of Manila". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Environment — Manila". City-Data. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ↑ Rambo Talabong (June 6, 2017). "Estrada approves building 3 islands at Manila Bay for new commercial district". Rappler. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ↑ Aie Balagtas See (June 7, 2017). "Erap OKs fourth reclamation project in Manila Bay". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ↑ Rambo Talabong (May 12, 2017). "Manila to relocate 7,000 families in esteros". Rappler. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ↑ Lozada, Bong (March 27, 2014). "Metro Manila is world's second riskiest capital to live in–poll". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ Rimando, Rolly; Rolly E. Rimando; Peter L.K. Knuepfer (February 10, 2004). "Neotectonics of the Marikina Valley fault system (MVFS) and tectonic framework of structures in northern and central Luzon, Philippines". ScienceDirect. pp. 17–38. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Fire and Quake in the construction of old Manila". The Frequency of Earthquakes in Manila. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- 1 2 "The City of God: Churches, Convents and Monasteries" Discovering Philippines. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Temperatures drop further in Baguio, MM". Philippine Star. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ "Metro Manila temperature soars to 36.2C". ABS-CBN. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ "Manila". Jeepneyguide. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Climatological Normals of the Philippines (1951–1985) (PAGASA 1987)" (PDF). PAGASA. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ↑ "Manila, Luzon Climate & Temperature". Climatemps.com. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ↑ "City Profiles:Manila, Philippines". United Nations. Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ↑ Alave, Kristine L. (18 August 2004). "METRO MANILA AIR POLLUTED BEYOND ACCEPTABLE LEVELS". Clean Air Initiative – Asia. Manila: Cleanairnet.org. Archived from the original on December 3, 2005. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "POLLUTION ADVERSELY AFFECTS 98% OF METRO MANILA RESIDENTS". Hong Kong: Cleanairnet.org. 31 January 2005. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Air pollution is killing Manila". GetRealPhilippines. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ Fajardo, Feliciano (1995). Economics. Philippines: Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 357. ISBN 978-971-23-1794-1. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ de Guzman, Lawrence (11 November 2006). "Pasig now one of world's most polluted rivers". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are the upcoming tropical cyclone names?". NOAA. Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan (September 29, 2009). "The Manila Floods: Why Wasn't the City Prepared?". TIME. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Presidential Decree Number 274, Pertaining to the Preservation, Beautification, Improvement, and Gainful Utilization of the Pasig River, Providing for the Regulation and Control of the Pollution of the River and Its Banks In Order to Enhance Its Development, Thereby Maximizing Its Utilization for Socio-Economic Purposes.". Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Santelices, Menchit. "A dying river comes back to life". Philippine Information Agency. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008.

- ↑ "Estero de San Miguel: The great transformation". Yahoo! Philippines. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Republic Act No. 409". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ "Manila : : Architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ↑ "Escolta Street tour shows retro architecture and why it's worth reviving as a gimmick place". News5. Archived from the original on March 2, 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ Jenny F. Manongdo (June 13, 2016). "Culture agency moves to restore 'Manila, Paris of the East' image". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Let's bring back the glory days of Manila with the rehabilitation of the Met!". Coconuts Manila. June 17, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ↑ Lila Ramos Shahani (May 11, 2015). "Living on a Fault Line: Manila in a 7.2 Earthquake". The Philippine Star. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ↑ Census of Population (2015). "National Capital Region (NCR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Census of Population and Housing (2010). "National Capital Region (NCR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ↑ Census of Population (1995, 2000 and 2007). "National Capital Region (NCR)". Total Population by Province, City and Municipality. NSO. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011.

- ↑ "Province of Metro Manila, 1st (Not a Province)". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "World's Densest Cities". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- 1 2 "Manila – The city, History, Sister cities" (PDF). Cambridge Encyclopedia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2010. (from Webcite archive)

- ↑ "The Philippines: The Spanish Period". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Population estimates for Metro Manila, Philippines, 1950–2015".

- ↑ "Profile of Makati City" (PDF). Makati City Government.

- ↑ Mercurio, Richmond S. "Richmond S. Mercurio". Philippine Star. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ↑ Tony Macapagal (February 8, 2017). "Manila dads hail fast CTO service". The Standard. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ↑ "Rankings". Cities and Municipalities Competitiveness Index. Retrieved 9 January 2017.