Maloti Mountains

| Maloti | |

|---|---|

| Maluti | |

Peaks of the Maloti range in Lesotho | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Thabana Ntlenyana |

| Elevation | 3,482 m (11,424 ft) |

| Listing | Mountain ranges of South Africa |

| Coordinates | 29°0′0″S 28°25′0″E / 29.00000°S 28.41667°ECoordinates: 29°0′0″S 28°25′0″E / 29.00000°S 28.41667°E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 150 km (93 mi) NW/SE |

| Width | 90 km (56 mi) NE/SW |

| Geography | |

Maloti | |

| Countries | Lesotho and South Africa |

| Region | Southern Africa |

| Parent range | Drakensberg |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Kaapvaal craton |

| Age of rock | Neoarchean to early Paleoproterozoic |

| Type of rock | Bushveld igneous complex, sandstone |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | From Maseru or Phuthaditjhaba |

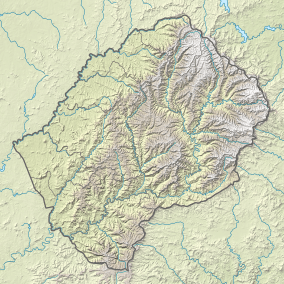

The Maloti Mountains, also spelled Maluti (Afrikaans: Malutiberge), are a mountain range of the highlands of the Kingdom of Lesotho. They extend for about 100 km into the Free State. The Maloti Range is part of the Drakensberg system that includes ranges across large areas of South Africa. “Maloti” is also the plural for Loti, the currency of the Kingdom of Lesotho. The range forms the northern portion of the boundary between the Butha-Buthe District in Lesotho and South Africa’s Orange Free State.[1]

Physiography

The range forms a high alpine basalt plateau up to 3,400 m (11,200 ft) in height. It is located between Butha-Buthe District in Lesotho and the Free State Province of South Africa. The highest point, 3,482 m (11,424 ft) high Thabana Ntlenyana, is located in the north-east of the range. It is the highest peak of Southern Africa, and the highest in Africa south of the Kilimanjaro.[2] The 3,291 m (10,797 ft) high Namahadipiek, the highest mountain in the Free State, is also part of the Maloti Range. The mountains form a continuous upland area of rounded peaks with incised deep valleys on the flanks which drain into the Senqu River. Snow and frost may be found even in summer on the highest peaks.[1]

The bioregion is made up of sandstone and shale overlain by basalt. The mountain’s rough terrain makes it less accessible to visitors and prevented any significant exploitation of its mineral resources. The topography differs between the two countries. In Lesotho, the mountain range is made up of a continuous landscape of more rounded mountains with deep valleys that drain into Lesotho’s Senqu River, known as the Orange River in South Africa. In South Africa, sheer basalt cliffs drop off from the transfrontier into foothills composed of sandstone. This rock is incised by the rivers that flow eastwards.[1]

Drainage

The area is usually dry between May and September, which are largely winter months. It experiences snow every month of the year. The snow and drainage, which includes the Orange River, Tugela River and the tributaries of the Caledon River make this the source of much of Southern Africa’s fresh water.[3]

The sources of two of the principal rivers in South Africa, the Orange River, known as Senqu in Lesotho, and the Tugela River, are in these mountains. Tributaries of the Caledon River, known as Mohokare in Lesotho, which forms the country's western border, also rise here, and the Makhaleng River rises on the flanks of Machache (2,886 m (9,469 ft)).[4]

Economic activities

The two countries are also largely economically different—with Lesotho being one of the least developed countries in the world and South Africa being among Africa’s biggest economies. Socially, Lesotho and the Orange Free State both have Sotho as the dominant culture. Like much of Lesotho, this bioregion is significantly rural and with limited commercial activity. South Africa has established and diversified the economy of the area, using it for agriculture and tourism.[1] The topography in the South African portion makes it more accessible and useful for livestock farming, crop production and tourism. Temperature extremes in winter and summer also cause seasonal limitations.[1]

Protected areas

In the early 1980s, officials from Lesotho approached the Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (previously known as the Natal Parks Board) to propose the collaborative management of the bioregion to protect its natural and cultural heritage. This eventually led to the signing of the Giant’s Castle Declaration in 1997. Since then the two countries have been making a concerted effort towards the protection and sustainable use of the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains.[1]

The Golden Gate Highlands National Park includes parts of the northeastern end of the Maloti Range. Other parks in this high mountain area are the Sehlabathebe National Park in Lesotho and the uKhahlamba / Drakensberg Park spanning parts of both KwaZulu-Natal province and Lesotho. These parks are part of the Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation Area.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zunckel, Kevan. 2010. Connectivity Conservation Management: A Global Guide (with Particular Reference to Mountain Connectivity Conservation). Earthscan. p.77-79

- ↑ Thabana Ntlenyana (mountain, Lesotho) - Britannica Online

- ↑ Maloti Mountains - Britannica Online

- ↑ J.-P. vanden Bossche; G. M. Bernacsek (1990). Source Book for the Inland Fishery Resources of Africa. Food & Agriculture Org. p. 93. ISBN 978-92-5-102983-1.

- ↑ Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation Area Archived 2012-01-30 at the Wayback Machine.