Malthusian catastrophe

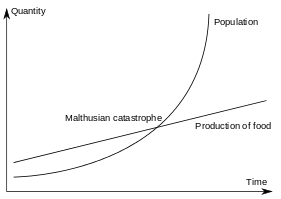

A Malthusian catastrophe (also known as Malthusian check or Malthusian spectre) is a prediction of a forced return to subsistence-level conditions once population growth has outpaced agricultural production.

Thomas Malthus

In 1779, Thomas Malthus wrote:

Famine seems to be the last, the most dreadful resource of nature. The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world.

Notwithstanding the apocalyptic image conveyed by this particular paragraph, Malthus himself did not subscribe to the notion that mankind was fated for a "catastrophe" due to population overshooting resources. Rather, he believed that population growth was generally restricted by available resources:

The passion between the sexes has appeared in every age to be so nearly the same that it may always be considered, in algebraic language, as a given quantity. The great law of necessity which prevents population from increasing in any country beyond the food which it can either produce or acquire, is a law so open to our view...that we cannot for a moment doubt it. The different modes which nature takes to prevent or repress a redundant population do not appear, indeed, to us so certain and regular, but though we cannot always predict the mode we may with certainty predict the fact.— Thomas Malthus, 1798. An Essay on the Principle of Population. Chapter IV.

Neo-Malthusian theory

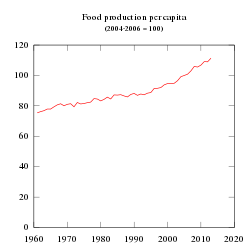

After World War II, mechanized agriculture produced a dramatic increase in productivity of agriculture and the Green Revolution greatly increased crop yields, expanding the world's food supply while lowering food prices. In response, the growth rate of the world's population accelerated rapidly, resulting in predictions by Paul R. Ehrlich, Simon Hopkins,[3] and many others of an imminent Malthusian catastrophe. However, populations of most developed countries grew slowly enough to be outpaced by gains in productivity.

By the early 21st century, many technologically developed countries had passed through the demographic transition, a complex social development encompassing a drop in total fertility rates in response to various fertility factors, including lower infant mortality, increased urbanization, and a wider availability of effective birth control.

On the assumption that the demographic transition is now spreading from the developed countries to less developed countries, the United Nations Population Fund estimates that human population may peak in the late 21st century rather than continue to grow until it has exhausted available resources.[4]

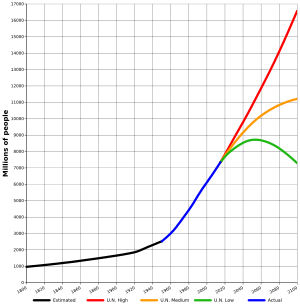

Historians have estimated the total human population back to 10,000 BC.[6] The figure on the right shows the trend of total population from 1800 to 2005, and from there in three projections out to 2100 (low, medium, and high).[4] The United Nations population projections out to 2100 (the red, orange, and green lines) show a possible peak in the world's population occurring by 2040 in the first scenario, and by 2100 in the second scenario, and never ending growth in the third.

The graph of annual growth rates (at the top of the page) does not appear exactly as one would expect for long-term exponential growth. For exponential growth it should be a straight line at constant height, whereas in fact the graph from 1800 to 2005 is dominated by an enormous hump that began about 1920, peaked in the mid-1960s, and has been steadily eroding away for the last 40 years. The sharp fluctuation between 1959 and 1960 was due to the combined effects of the Great Leap Forward and a natural disaster in China.[7] Also visible on this graph are the effects of the Great Depression, the two world wars, and possibly also the 1918 flu pandemic.

Though short-term trends, even on the scale of decades or centuries, cannot prove or disprove the existence of mechanisms promoting a Malthusian catastrophe over longer periods, the prosperity of a major fraction of the human population at the beginning of the 21st century, and the debatability of the predictions for ecological collapse made by Paul R. Ehrlich in the 1960s and 1970s, has led some people, such as economist Julian L. Simon, to question its inevitability.[8]

A 2004 study by a group of prominent economists and ecologists, including Kenneth Arrow and Paul Ehrlich[9] suggests that the central concerns regarding sustainability have shifted from population growth to the consumption/savings ratio, due to shifts in population growth rates since the 1970s. Empirical estimates show that public policy (taxes or the establishment of more complete property rights) can promote more efficient consumption and investment that are sustainable in an ecological sense; that is, given the current (relatively low) population growth rate, the Malthusian catastrophe can be avoided by either a shift in consumer preferences or public policy that induces a similar shift.

A 2002 study[10] by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization predicts that world food production will be in excess of the needs of the human population by the year 2030; however, that source also states that hundreds of millions will remain hungry (presumably due to economic realities and political issues).

Criticism

Since the mid-19th Century, many economists have suggested that humanity will not face a Malthusian catastrophe because "necessity is the mother of invention" and "the market will fix itself".

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that Malthus failed to recognize a crucial difference between humans and other species. In capitalist societies, as Engels put it, scientific and technological "progress is as unlimited and at least as rapid as that of population".[11] Marx argued, even more broadly, that the growth of both a human population in toto and the "relative surplus population" within it, occurred in direct proportion to accumulation.[12]

Henry George criticized Malthus's view that population growth was a cause of poverty, arguing that poverty was caused by the concentration of ownership of land and natural resources. George noted that humans are distinct from other species, because unlike most species humans can use their minds to leverage the reproductive forces of nature to their advantage. He wrote, "Both the jayhawk and the man eat chickens; but the more jayhawks, the fewer chickens, while the more men, the more chickens." [13]

Ester Boserup suggested that population levels determined agricultural methods, rather than agricultural methods determining population.[14]

Julian Simon was another economist who argued that there could be no global Malthusian catastrophe, because of two factors: (1) the existence of new knowledge, and educated people to take advantage of it, and (2) "economic freedom", that is, the ability of the world to increase production when there is a profitable opportunity to do so.[15]

In contrast to these criticisms, some individuals, such as Joseph Tainter, argue that science has diminishing marginal returns[16] and that scientific progress is becoming more difficult, harder to achieve, and more costly.

See also

- Demographic trap

- The dismal science

- Food security

- Human overpopulation

- Malthusian trap

- Overshoot (population)

- Olduvai theory

- Pledge two or fewer (campaign for smaller families)

- r/K selection theory

Notes

- ↑ Oxford World's Classics reprint

- ↑ Fischer, R. A.; Byerlee, Eric; Edmeades, E. O. "Can Technology Deliver on the Yield Challenge to 2050" (PDF). Expert Meeting on How to Feed the World. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: 12.

- ↑ Hopkins, Simon (1966). A Systematic Foray into the Future. Barker Books. pp. 513–569.

- 1 2 "2004 UN Population Projections, 2004." (PDF).

- ↑ Data source: http://faostat3.fao.org/download/Q/QI/E, see graph metadata for further details.

- ↑ "Historical Estimates of World Population, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2006.".

- ↑ "International Data Base".

- ↑ Simon, Julian L, "More People, Greater Wealth, More Resources, Healthier Environment", Economic Affairs: J. Inst. Econ. Affairs, April 1994.

- ↑ Arrow, K., P. Dasgupta, L. Goulder, G. Daily, P. Ehrlich, G. Heal, S. Levin, K. Mäler, S. Schneider, D. Starrett and B. Walker, "Are We Consuming Too Much" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3), 147-172, 2004.

- ↑ World agriculture 2030: Global food production will exceed population growth August 20, 2002.

- ↑ Engels, Friedrich."Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy", Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, 1844, pg.1.

- ↑ Karl Marx (transl. Ben Fowkes), Capital Volume 1, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1976 (originally 1867), pp. 782–802.

- ↑ Progress and Poverty, Chapter 7, Malthus vs. Facts in http://www.henrygeorge.org/pchp7.htm

- ↑ Ester Boserup, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure

- ↑ The Ultimate Resource II: People, Materials, and Environment in http://www.juliansimon.com/writings/Ultimate_Resource/

- ↑ Tainter, Joseph: The Collapse of Complex Societies, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2003.

References

- Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00414-4

- Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00559-0 See especially Chapter 2 of this book

- Korotayev A. & Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends in Africa. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00560-4

- Malthus, Thomas Robert (1826). "An Essay on the Principle of Population: A View of its Past and Present Effects on Human Happiness; with an Inquiry into Our Prospects Respecting the Future Removal or Mitigation of the Evils which It Occasions" (Sixth ed.). London: John Murray. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- Turchin, P., et al., eds. (2007). History & Mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of Complex Societies. Moscow: KomKniga. ISBN 5-484-01002-0

- A Trap At The Escape From The Trap? Demographic-Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics 2/2 (2011): 1-28.

External links

- Essay on life of Thomas Malthus

- Malthus' Essay on the Principle of Population

- David Friedman's essay arguing against Malthus' conclusions

- United Nations Population Division World Population Trends homepage