Mallinckrodt, Inc. v. Medipart, Inc.

Mallinckrodt, Inc. v. Medipart, Inc., 976 F.2d 700 (Fed. Cir. 1992), is a decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, in which the court appeared to overrule or drastically limit many years of U.S. Supreme Court precedent affirming the patent exhaustion doctrine, for example in Bauer & Cie. v. O'Donnell.[1]

Factual background

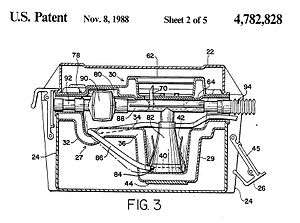

According to the opinions in the case, the plaintiff Mallinckrodt owned a patent on a device for dispensing a radioactive mist used in taking diagnostic lung X-rays, and for trapping the mist after use. Mallinckrodt sold the device to hospitals for about $40 or $50. Hospital personnel would load the device with a suitable radioactive fluid to perform a diagnostic procedure on a patient, use the device, and then discard it. Mallinckrodt labeled the devices it sold with the notice “Single use only.” Because the device itself cost approximately $10 to make but was sold for four or five times that, most of the purchase price that hospitals paid Mallinckrodt apparently represented the value of the patent (or the patented technology). This fact apparently led the defendant Medipart to go into the recycling business, in which Mallinckrodt itself had no direct interest (it chose to sell only new devices). For a $20 recycling fee, Medipart would clean one of the devices for a hospital, replace some parts, subject the device to gamma radiation to kill germs, and return it to the hospital for reuse. The district court and court of appeals opinions do not support the claim that a health or safety problem existed. However, Mallinckrodt asserted to the court that "potential adverse consequences, such as infectious disease transmission” provided the reason for its imposing the restriction against reuse.

Litigation and rulings

Since Medipart and hospitals dealing with it were defying Mallinckrodt's “Single use only” label and adversely affecting its business, Mallinckrodt sued the recycler for patent infringement. Medipart then moved to dismiss the patent infringement claim because of the exhaustion doctrine; the district court agreed and granted summary judgment.

Mallinckrodt appealed and the Federal Circuit reversed. It held that, despite the breadth of the language of the Supreme Court’s decisions on exhaustion, the apparently absolute rule against post-sale restrictions on patentees' customers should apply only to price-fixes and tie-ins. In cases not involving price-fixes or tie-ins, such as this one, patentees were free to limit their customer's use of products as long as the restrictions did not so greatly hinder competition as to amount to an antitrust violation.

The reasoning of the Mallinckrodt court proceeds along the following lines:

- Most or many of the Supreme Court's line of exhaustion doctrine cases involved price-fixing or tie-ins.

- Therefore, they could have been decided on the legal theory that price-fixes and tie-ins are illegal per se.

- Any sweeping language by the Supreme Court about property rights, and about post-sale restrictions on customers’ use of patented products not being patent infringement, is mere obiter dictum that may properly be disregarded in cases not involving price-fixes or tie-ins.

The ruling in Mallinckrodt had two principal prongs, both of which figured in subsequent Federal Circuit decisions. First, the main holding was that patent owners could sell patented goods with a restrictive notice and thereby restrict the disposition of the goods by the purchasers, with the sole exception of price-fixing and tie-in restrictions.[2] Thus, the Mallinckrodt court had said that, “[u]nless the condition violates some other law or policy (in the patent field, notably the misuse or antitrust law),” patentees enjoyed freedom of contract to impose post-sale restrictions on customers under a rule of reason. “The appropriate criterion” for determining the limits of this freedom to impose restrictions, according to the Federal Circuit, “is whether [the patentee’s or licensor's] restriction is reasonably within the patent grant, or whether the patentee has ventured beyond the patent grant and into behavior having an anticompetitive effect not justifiable under the rule of reason.”[3]

The second prong concerned patent misuse. According to the court, the legal tests for post-sale restrictions and for misuse were alike, outside the tie-in and price fixing area: “To sustain a misuse defense involving a licensing arrangement not held to have been per se anticompetitive by the Supreme Court, a factual determination must reveal that the overall effect of the license tends to restrain competition unlawfully in an appropriately defined relevant market.”[4]

Other Federal Circuit decisions have followed the ruling of the Mallinckrodt misuse prong.[5]

Impact

Until the Federal Circuit’s Mallinckrodt decision, an unbroken line of Supreme Court and lower court precedents held that the patentee’s patent right over a product that the patentee sold (or that a licensee authorised to make a sale sold) ended at the point of sale.[6] Accordingly, a customer did not commit patent infringement by disobeying a notice, contract, or other “remote control” limitation that the patentee sought to impose on the use of goods that it had sold to the customer. The Supreme Court’s rationale in exhaustion doctrine cases was that the purchasers acquired an unlimited property right in the patented products, and that it was inconsistent with that property right for the patentee to control how the purchasers used or disposed of the products once they had become the property of the purchasers. The legal reasoning in all of these decisions begins with that principle, and the rest of the analysis consists of applying it to the particular facts. Until the 2008 Supreme Court decision in the Quanta case, however, the Federal Circuit's Mallinckrodt decision superseded the earlier line of exhaustion cases.

It has been observed that under the doctrine of the Mallinckrodt case, a patentee may sell its patented product with a legally effective notice prohibiting purchasers from engaging in any of the following conduct:[7]

- Prohibiting repair of patented products and parts replacement (for example, the seller labels the device: "Licensed for use only until element B wears out")

- Prohibiting modification or enhancement of patented devices (for example, the manufacturer places a notice on the machine stating "Machine licensed for use only as is, without modification")

- Charging different prices in different niche markets and preventing arbitrage from one market to another (for example, selling semiconductor chips labeled "For use only in microwave oven market")

- Permitting resale only in specified channel of distribution

The Federal Circuit’s Mallinckrodt doctrine has not avoided criticism as allegedly stating legal rules that contradict Supreme Court decisions. Thus in 2007, the United States Solicitor General filed an amicus curiae brief in Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc.,[8] stating, as to the first prong, "The test adopted by the Federal Circuit in Mallinckrodt thus reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the role and scope of the patent-exhaustion doctrine. ... The court of appeals’ approach cannot be reconciled with those [Supreme Court] precedents,"[9] and more generally that the Federal Circuit’s Quanta opinion based on Mallinckrodt “rests on the same erroneous understanding of patent exhaustion that infuses the Federal Circuit’s approach to this area of the law."[10]

The effect of Mallinckrodt may have been restricted by the Supreme Court's 2008 decision in Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc., which broadly reaffirmed the exhaustion doctrine without mentioning Mallinckrodt. It is too early to state, however, what the impact of Quanta on the Mallinckrodt doctrine will be.

Continued viability questioned

In April 2015, the Federal Circuit sua sponte called for briefing and amicus curiae participation in an en banc consideration of whether Mallinckrodt should be overruled in light of the recent Supreme Court decision in the Quanta case. The court ordered:

In light of Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc., 553 U.S. 617 (2008), should this court overrule Mallinckrodt, Inc. v. Medipart, Inc., 976 F.2d 700 (Fed. Cir. 1992), to the extent it ruled that a sale of a patented article, when the sale is made under a restriction that is otherwise lawful and within the scope of the patent grant, does not give rise to patent exhaustion?[11]

The Federal Circuit then re-affirmed Mallinckrodt but on December 2, 2016, the Supreme Court granted certiorari.[12] The case was argued in 2017 and was decided in June 2017; the Supreme Court emphatically rejected enforcement of post-sale patent rights, thereby disapproving the decision in Mallinckrodt.

References

- ↑ Richard H. Stern, The Unobserved Demise of the Exhaustion Doctrine in US Patent Law: Mallinckrodt v. Medipart, 15 EUR. INTELL. PROP. REV. 460 (1993).

- ↑ Richard H. Stern, Quanta Computer Inc v LGE Electronics Inc—Comments on the Reaffirmance of the Exhaustion Doctrine in the United States, [2008] EUR. INTELL. PROP. REV. 527.

- ↑ Mallinckrodt, 976 F.2d at 708.

- ↑ Mallinckrodt, 976 F.2d at 706 (quoting Windsurfing Int’l, Inc. v. AMF, Inc., 782 F.2d 995, 1001-02 (Fed. Cir. 1986)).

- ↑ See, e.g., U.S. Philips Corp. v. International Trade Com'n, 424 F.3d 1179, 1185 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (“If the particular licensing arrangement in question is not one of those specific practices that has been held to constitute per se misuse, it will be analyzed under the rule of reason. We have held that under the rule of reason, a practice is impermissible only if its effect is to restrain competition in a relevant market.") (citations omitted); Monsanto Co. v. McFarling, 363 F.3d 1336, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2004.

- ↑ See opinion of US Supreme Court in Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc., 128 S. Ct. 2109 (2008) (“The longstanding doctrine of patent exhaustion provides that the initial authorized sale of a patented item terminates all patent rights to that item.”). The Court’s opinion summarizes 19th and 20th Century case law.

- ↑ See Richard H. Stern, Post-Sale Patent Restrictions After Mallinckrodt -- An Idea in Search of Definition, 5 ALBANY L.J. SCI. & TECH. 1 (1994).

- ↑ 128 S. Ct. 2109 (2008).

- ↑ Brief for United States as amicus curiae in Quanta, at 23; see also id. at 6 ("In recent years, the first-sale doctrine has evolved in the Federal Circuit in a manner that is at odds with this Court’s precedents."); id. at 22 ("The Federal Circuit misreads Univis as standing only for the proposition that restrictions that have been found to be unlawful restraints on trade in the patent context, such as “price-fixing or tying” arrangements, cannot be enforced in a patent-infringement suit.").

- ↑ Id. at 30.

- ↑ Lexmark Int'l, Inc. v. Impression Prods., Inc., 785 F.3d 565 (Fed. Cir. 2015). The oral argument took place on Oct. 2, 2015.

- ↑ Impression Prods. v. Lexmark Int'l, Inc., 2016 U.S. LEXIS 7275.