Malibou Lake, California

| Malibou Lake | |

|---|---|

Malibou Lake in Los Angeles | |

| Location | Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 34°06′25″N 118°45′25″W / 34.107°N 118.757°WCoordinates: 34°06′25″N 118°45′25″W / 34.107°N 118.757°W |

| Primary inflows | From the Medea and the Triunfo creeks |

| Primary outflows | Outlet from dam into Malibu Creek |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Surface area | 350 acres (140 ha) |

| Max. depth | 27 feet (8.2 m) |

| Shore length1 | 3 km (1.9 mi) |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Malibou Lake is a small and historic lake and community in the Santa Monica Mountains near Agoura Hills, California, USA.[1] Located within Malibu Creek State Park, and almost completely surrounded by the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area,[2] it is situated between Malibu Beach and the Conejo Valley. It was created in 1922 after a dam was built at the confluence of two creeks, the lake, and community of 250 residents[2] are private.[3] eBird shows data that Malibou Lake is a well travelled migratory bird stop.

The lake and the surrounding property of 350 acres, consisting of rugged mountain terrain, exclusive ranch houses, cabins and a club, has been a popular venue for filming due to its proximity to the Hollywood studios. About 100 Hollywood movies have been filmed since the silent film period.

A DVD made in 2007 has clippings of all films made in the backdrop of the Malibou lake and runs for two hours.[4]

Etymology

Malibu was originally settled by the Chumash, Native Americans whose territory extended loosely from the San Joaquin Valley to San Luis Obispo to Malibu, as well as several islands off the southern coast of California. They named it "Humaliwo"[5] or "the surf sounds loudly." The region's name, originally given by the Spanish, derives from this, as the "Hu" syllable is not stressed.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Malibu area was going through a significant turning point. The original Chumash inhabitants were all but gone, and the Spanish who had "civilized" them had found their California in the hands of mostly Caucasian mountain men. As the Santa Monica Mountains became a white, English-speaking community, ties with the area's Spanish roots were deliberately dropped. Hence, despite being aware of the Spanish spelling of Malibu, those who settled the Cornell area often spelt it 'Malibou', so as to Anglicize it.[4]

History

In 1922, George Wilson and Bertram Lackey bought 350 acres of land near Cornell with the vision of creating a remote residential community surrounding a lake. In 1922, they formed the Malibou Lake Club (later the Malibou Lake Mountain Club) For nearly four years Malibou "Lake" remained dry as a bone. Because of this, the Malibou Lake Mountain Club received harsh criticism from early cabin owners, who had purchased properties for up to $700 along roads such as "Lakeside Drive".[2][6] Finally on April 5, 1926, a late spring storm produced nearly five inches of rain. The vast hillsides nearby drained millions of gallons of water into Medea and Triunfo Creeks and Malibou Lake was filled for the first time. The founding members threw a party that lasted for days.[6][7] The club land is rich with Live Oak and Sycamore trees, and the trees of the riparian woodland.[2]

A historic 1936 clubhouse by well respected early Los Angeles architectural firm, Russell and Alpaugh stands today. The Malibou Lake Mountain Club clubhouse has a 2100 sq ft ballroom and a 475 sqft receiving room, a 1500 sqft patio, immediately adjacent gardens, a swimming pool and a tennis court and 18 ensuite 10' x 13' club member guest rooms (guest rooms not in use).

A larger MLMC clubhouse burned down back in 1936. Originally built in 1924, that Malibou Lake Clubhouse had 24 bedrooms, a lounge, a dining room, a stage, locker rooms, a trading post, a tennis court, a fleet of rowboats, and swimming/changing facilities.[7] 1936 fire and[4][8]

In 1961, Malibu Lake suffered severe drought and dried up. Attempts to resurrect the situation were initially unsuccessful.[2] Over the past few decades the community of Malibu Lake has proved successful in preserving the lake area and resisting various proposals for mass development in the area.[2] This location (within the 30 mile studio range) has been a popular location since the silent movie era for films, and has been depicted as part of the Mississippi River, northern woods of Canada, swamps of Philippines and an African jungle.[3][4]

Geography

Malibou Lake is located in the Santa Monica Mountains, half a mile south of Mulholland Highway, and over the hill, north of Malibu itself. It can also be reached via the Ventura (101) Freeway, approximately 3 miles to the north.[2][9] The Malibu Lake area includes parts of Point Dume and Thousand Oaks.[10] The lake sits at the bottom of a sharp defile where the confluence of Medea and Triunfo Creeks forms Malibu Creek.[11] Here, the canyon floor widens into a valley that includes the lake, which occasionally dries out.[2]

The lake is situated in the midst of the Santa Monica Mountains Recreation Area. According to the official tourism portal, many large ranches had been set up here by Ronald Reagan. The lake periphery measures 3 km and its shores are studded with many film settings and homes. The depth of water in the lake is ranges to 25 ft which provided the ideal location for the heroes of the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid to jump from the top of a cliff. A similar stunt act of jumping into the lake was performed by James Coburn, for the film “Our Man Flint”.[3][12][13][14]

The Santa Monica mountains and the Agoura hills, which form the catchment of the lake, and the creeks which drain into the lake are adjacent to Malibu Creek State Park. These locations were part of the CBS-TV series M*A*S*H screened during 1972 to 1983.[12]

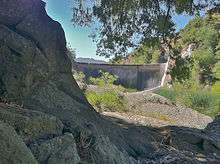

A gated dam-bridge is located at the lake's southern end.[15] When the area receives 4 inches (100 mm) or more of rain, the lake often overflows.[16] The water flows down Malibu Creek to the ocean at the Malibu Lagoon.

Film location

Malibou Lake has been used as a location or setting for many films and television programs.[17] These include Hollywood movies, such as The Ring, a 2002 American psychological horror film, the 1931 version of Frankenstein,[18] and the 1956 Oscar-nominated film The Bad Seed. Two famous actresses also shot movies at Malibu Lake. Claudette Colbert appears in "The Man from Yesterday" and Betty Grable appeared there in "Thrill of a Lifetime". The Postman Always Rings Twice, a 1946 movie starring Lana Turner and John Garfield, mentions Malibu Lake, but the lake does not appear in the film. Other notable films and programs include:

- (1933) Tillie and Gus with WC Fields

- (1936) Phantom Patrol

- (1937) Quality Street

- (1937) Make a Wish

- (1939) Gone with the Wind

- (1940) The Great Dictator[18]

- (1942) Watch on the Rhine

- (1946) The Postman Always Rings Twice

- (1958) I Married a Monster from Outer Space

- (1961) Return to Peyton Place

- (1965) Funny About Love

- (1965) How to Stuff a Wild Bikini

- (1970) M*A*S*H

- (1976) Rich Man, Poor Man[19]

- (1999) The Story of Us[18]

- (2002) The Ring[18]

- (2005) Must Love Dogs[18]

- Crazy Mama[18]

Malibu Lake holds more than a 100 film credits.[1]

Notable former residents

- Arthur Edeson, American film cinematographer[20]

- Elizabeth Montgomery, American film and television actress[21]

- Ronald Reagan, President of the United States[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 Rasmussen, Cecilia. "Malibou Lake has played its part in movie history". latimes.com. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pitt, Leonard; Pitt, Dale (1997). Los Angeles A to Z: an encyclopedia of the city and county. University of California Press. pp. 313–. ISBN 978-0-520-20530-7. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 "History of Malibou lake". Official web site of Malibu Lake. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Low Down:Malibou Lake". Agourahills.patch.com. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Humaliwo: An Ethnographic Overview of the Chumas in Malibu

- 1 2 Federal Writers' Project. Los Angeles: A Guide to the City and Its Environs. US History Publishers. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-60354-053-7. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- 1 2 "History". Malibou Lake Mountain Club. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ↑ Rivellino, Dolores (November 2007). The Malibu Cookbook: A Memoir by the Godmother of Malibu. AuthorHouse. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4259-1434-9. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ↑ Jaeger, Edmund C.; Smith, Arthur Clayton (January 1966). Introduction to the natural history of southern California. University of California Press. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-0-520-03245-3. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Geological Survey (U.S.) (1961). Geological Survey bulletin. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Geological Survey; Washington, D.C. pp. 461–. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Federal Writers' Project. Los Angeles: A Guide to the City and Its Environs. US History Publishers. pp. 383–. ISBN 978-1-60354-053-7. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- 1 2 "Local peaks were a convincing cinematic stand-in". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Local peaks were a convincing cinematic stand-in". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Three Magical Miles". Media: Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Hiking Malibu Creek". modernhiker.com. February 13, 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Stewart, Jocelyn (February 15, 1992). "Flooding a Part of Life on Shores at Malibou Lake Aftermath: Residents who returned to their homes to assess the damage take it in stride. Such disasters are a part of the community's history, they say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Loesing, John. "Author tells rich and colorful history of Malibou Lake". theacorn.com. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Medved, Harry; Akiyama, Bruce (27 June 2006). Hollywood Escapes: The Moviegoer's Guide to Exploring Southern California's Great Outdoors. Macmillan. pp. 273–. ISBN 978-0-312-30856-8. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Laura Randall (1 April 2006). 60 hikes within 60 miles, Los Angeles: including San Bernardino, Pasadena, and Orange counties. Menasha Ridge Press. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-0-89732-638-4. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Mank, Gregory William (13 May 2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. McFarland. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-0-7864-3480-0. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Craig Sheffer puts Malibou Lake home on the market". Los Angeles Times. June 30, 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ↑ Sutherland, James (4 September 2008). Ronald Reagan. Penguin. pp. 245–. ISBN 978-0-670-06345-1. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malibu Lake. |