Maharashtrian cuisine

|

| This article is part of the series |

| Indian cuisine |

|---|

|

Regional cuisines

|

|

Ingredients, types of food |

|

See also

|

|

Maharashtrian or Marathi cuisine is the cuisine of the Marathi people from the Indian state of Maharashtra. It has distinctive attributes, while sharing much with other Indian cuisines. Traditionally, Maharashtrians have considered their food to be more austere than others.

Maharashtrian cuisine includes mild and spicy dishes. Wheat, rice, jowar, bajri, vegetables, lentils and fruit are dietary staples. Peanuts and cashews are often served with vegetables. Meat is traditionally used sparsely or by the well off until recently, because of economic conditions and culture.

The urban population in metropolitan cities such as Mumbai, Pune and others has been influenced from other parts of India and abroad. For example, the Udupi dishes idli and dosa, as well as Chinese and Western dishes, are quite popular in home cooking and in restaurants.

Distinctly Maharashtrian dishes include ukdiche modak, aluchi patal bhaji and Thalipeeth.

Regular meals and staple dishes

| Maharashtrian cuisine | |

|---|---|

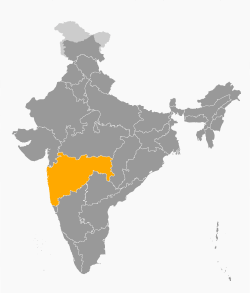

Location of Maharashtra in India | |

Map of Maharashtra with different regions and districts |

The Marathi people produced a diverse cuisine, which extends to the family level because each family uses its own unique combination of spices. The majority of Maharashtrians eat meat and eggs, but the Brahmin community is mostly lacto-vegetarian. The traditional staple food on Desh (the Deccan plateau) is usually bhakri, spiced cooked vegetables, dal and rice. However, North Maharashtrians and urbanites prefer roti or chapati, which is a plain bread made with wheat flour.

In the coastal Konkan region, rice is the traditional staple food. Wet coconut and coconut milk are used in many dishes. Marathi communities indigenous to Mumbai and North Konkan have their own distinct cuisine.[note 1] In South Konkan, near Malvan, another independent cuisine developed called Malvani cuisine, which is predominantly non-vegetarian. Kombdi vade, fish preparations and baked preparations are more popular there.

In the Vidarbha region, little coconut is used in daily preparations but dry coconut and peanuts are used in dishes such as spicy savjis, as well as in mutton and chicken dishes.

Lacto-vegetarian dishes are based on six main class of ingredients including grains, legumes, vegetables, dairy products and spices.[1]

Grains

Staple dishes are based on a variety of flatbreads and rice. Flatbreads can be wheat-based, such as the traditional trigonal ghadichi poli [2] or the round chapati that is more common in urban areas. Bhakri is an unleavened bread made using from ragi or millet, bajra or bajri or jwari – and forms part of daily meals in rural areas.[3]

Millets

Traditionally, the staple grains of the inland Deccan plateau have been millets, jwari [4] and bajri.[5] These crops grow well in this dry and drought-prone region. In the coastal Konkan region the finger millet called ragi is used for bhakri.[6][7] The staple meal of the rural poor was traditionally as simple as bajra bhakri accompanied by just a raw onion, a dry chutney, or a gram flour preparation called jhunka.[8][9] This meal later became fashionable among the urban classes.

Wheat

Increased urbanization has increased wheat's popularity.[10] Wheat is used for making flatbreads called chapati, the deep-fried version called puri or the thick paratha. One of the ancient sought-after breads was Mande.[11] As with rice, flatbreads accompany a meal of vegetables or dairy items.

Rice

Rice is the staple food in the rural areas of coastal Konkan region. Rice is popular in all urban areas.[4] Local varieties such as the fragrant ambemohar have been popular in Western Maharashtra. In most instances, rice is boiled on its own and becomes part of a meal that includes other items. A popular dish is varan bhaat where steamed rice is mixed with plain dal that is prepared with pigeon peas, lemon juice, salt and ghee.[12] Khichdi is a popular rice dish made with rice, mung dal and spices. For special occasions, a dish called masalebhat made with rice, spices and vegetables is popular.

Dairy

Milk is important as a staple food.[13] Both cow milk and water buffalo milk are popular. Milk is used mainly for drinking, to add to tea or coffee or to make homemade yogurt. The yogurt is used as dressing for many salad or koshimbir dishes to prepare cultured buttermilk or as a side dish in a thali. Buttermilk is used in a drink called mattha by mixing it with spices. It may also be used in curry preparations.[14]

Vegetables

Until recently, canned or frozen food was not widely available in India. Therefore, the vegetables used in a meal widely depended on the season. For example, spring (March–May) is the season of cabbages, onions, potatoes, okra, guar tondali,[15] shevgyachya shenga, dudhi, marrow and padwal. Monsoon season (June–September) brings green leafy vegetables, such as aloo (marathi: आळू), or gourds such as karle, dodka and eggplant. Chili peppers, carrots, tomatoes, cauliflower, french beans and peas are available in the cooler climate of October to February.[16]

Vegetables are typically used in making bhaajis. Some bhaajis are made with a particular vegetable, while others are made with a combination. Bhaajis can be "dry" such as stir fry or "wet" as in the well-known curry. For example, fenugreek leaves can be used with mung dal to make a dry bhhaji or mixed with besan flour and buttermilk to make a curry preparation. Bhaaji requires the use of goda masala, consisting of a combination of onion, garlic, ginger, red chilli powder, green chillies, turmeric and mustard seeds. Depending on a family's caste or specific religious tradition, onions and garlic may be excluded. For example, a number of Hindu communities and other parts of India refrain from eating onions and garlic altogether during chaturmas, which broadly equals the monsoon.[17]

Leafy vegetables such as fenugreek, amaranth, beetroot, radish, dill, colocasia, spinach, ambadi, sorrel (Chuka in Marathi), chakwat, safflower (Kardai in Marathi) and tandulja are either stir-fried (pale bhaaji ) or made into a soup (patal bhaaji )[18] using buttermilk and gram flour.[19][20][21]

Many vegetables are used in salad preparations called koshimbirs or raita.[22] Most of these have yogurt as the other main ingredient. Koshimbirs popular include those based on radish, cucumber and tomato-onion combinations. Many raita require prior boiling or roasting of the vegetable as in the case of eggplant. Popular raita include those based on carrots, eggplant, pumpkin, dudhi and beetroot.

Legumes

Along with green vegetables, another class of popular food is various beans, either whole or split. Split beans are called dal and turned into amti or thin soup, added to vegetables such as dudhi. Dal may be cooked with rice to make khichadi. Whole beans are cooked as is or more popularly soaked in water until sprouted. Unlike Chinese cuisine, the beans are allowed to grow for only a day or two. Curries made out of sprouted beans are called usal and form an important source of proteins.[23] The beans are commonly peas, chick peas, mung, matki, urid kidney bean, black-eyed peas, kulith and toor (also called pigeon peas).[24] Out of the above toor and chick peas are staples.[4][25] The urid bean is the base for one of the most popular types of papadum.

Oil

Peanut oil[26] and safflower oil are the primary cooking oils, although sunflower oil and cottonseed oil are also used.[27] Clarified butter (called ghee) is often used for its distinct flavor.

Spices and herbs

Depending on region, religion and caste, Maharashtrian food can be mild to extremely spicy. Common spices include asafoetida, turmeric, mustard seeds, coriander, cumin, dried bay leaves, and chili powder. Other spices used especially for garam masala include cinnamon, cloves, black pepper, cardamom and nutmeg. Common herbs to impart flavor or to garnish a dish include curry leaves, and coriander leaves. Many common curry recipes call for garlic, onion, ginger and green chilli pepper. Ingredients that impart sour flavor to the food include yoghurt, tomatoes, tamarind paste, amsul skin[28] or unripe mangoes.

Meat and poultry

Chicken and goat are the most popular meats. Eggs are popular and exclusively come from chicken sources. Beef and pork are mainly consumed by Christian minorities and some Dalit communities.[29] However, these do not form part of traditional Maharashtrian cuisine.

Seafood

Seafood is a staple for many Konkan coastal communities.[30] Most of the recipes are based on marine fish, prawns and crab. A distinct Malvani cuisine of mainly seafood dishes is popular. Popular fish varieties include Bombay duck,[31] pomfret, bangda and surmai (kingfish). Seafood is used in recipes such as curries, pan-fried dishes and pilaf.

Miscellaneous ingredients

Other ingredients include oil seeds such as flax, karale,[32][33] coconut, peanuts, almonds and cashew nuts. Peanut powder and whole nuts are used in many preparations including, chutney, khosimbir and bhaaji. More-expensive nuts (almonds and cashew) are used for sweet dishes. Flax and karale seeds are used in making dry chutneys.[34] Traditionally, jaggery was used as the sweetening agent, but has been largely replaced by cane sugar. Fruit such as mango are used in many preparations including pickles, jams, drinks and sweet dishes. Bananas and jackfruit are also used. Peanut powder is often added to curry recipes.

Typical menus

Urban menus typically have wheat in the form of chapatis and plain rice as the main staples. Traditional rural households would have millet in form of bhakri on the Deccan plains and rice on the coast as respective staples.[35]

Typical breakfast items include misal, pohe, upma, sheera, sabudana khichadi and thalipeeth. In some households leftover rice from the previous night is fried with onions, turmeric and mustard seeds for breakfast, making phodnicha bhat. Typical Western breakfast items such as cereals, sliced bread and eggs, as well as South Indian items such as idli and dosa are also popular. Tea or coffee is served with breakfast.

Urban lunch and dinner menus

Vegetarian lunch and dinner plates in urban areas carry a combination of:

- Wheat flatbread such as chapati or ghadichi poli

- Boiled rice

- Salad or koshimbir based on onions, tomatoes or cucumber

- Papadum or related snacks such as sandge, kurdaya and sabudana papdya[36]

- Dry or fresh chutney, mango or lemon pickles

- Aamti or varan soup based on toor dal, other dals or kadhi. When usal is part of the menu, the aamti may be omitted.

- Vegetables with gravy based on seasonal availability such as egg plants, okra, potatoes, or cauliflower

- Dry leafy vegetables such as spinach

- Usal based on sprouted or unsprouted whole legumes

Apart from bread, rice, and chutney, other items may be substituted. Families that eat meat, fish and poultry may combine vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes, with rice and chapatis remaining the staples. Vegetable or non-vegetable items are essentially dips for the bread or for mixing with rice.

Traditional dinner items are arranged in a circular way. With salt placed at 12 o'clock, pickles, koshimbir and condiments are placed anti-clockwise of the salt. Vegetable preparations are arranged in a clockwise fashion with a sequence of leafy greens curry, dry vegetables, sprouted been curry (usal ) and dal. Rice is always on the periphery rather than in the center.[18]

Rural lunch and dinner menus

In the Konkan coastal area, boiled rice and rice nachni bhakri is the staple, with a combination of the vegetable and non-vegetable dishes described in the lunch and dinner menu.

In other areas of Maharashtra such as Desh, Maharashtra, Khandesh, Marathwada and Vidarbha, the traditional staple was bhakri with a combination of dal, and vegetables. The bhakri is increasingly replaced by wheat-based chapatis.[10]

Methods and equipment

Open stove cooking is the most commonly used cooking method. The traditional three-stone chulha has largely been replaced by kerosene or gas stoves. A stove may be used for cooking in many different ways:

- Phodani – Often translated as "tempering", is a cooking technique and garnish where spices such as mustard seeds, cumin seeds, turmeric, and sometimes other ingredients such as minced ginger and garlic are fried briefly in oil or ghee to liberate essential oils from cells and thus enhance their flavours. Other ingredients such as vegetables and meat are then added to the pan.[37][38] Phodani may be the first step in making a bhaaji, aamti or curry. It may also be the last step, as part of a garnish.

- Simmering – Most curries and bhaajis are simmered for the meat or vegetables to cook

- Deep frying – This is used for making fritters such as onion bhaji, or sweet fried dumplings (karanji)

- Pan frying – This is characterized by the use of minimal cooking oil or fat (compared to shallow frying or deep frying); typically using just enough oil to lubricate the pan. This method is used for cooking delicate items such as fish.

- Tawa – This is usually a concave metal pan used on an open stove for making unleavened flatbreads such as ghadichi poli, chapatis or bhakris.

- Steaming – This method is mainly used for specialties such as ukadiche modak, or aluchya wadya.

- Roasting – Vangyache bharit involves roasting eggplant over open fire prior to mashing and adding other ingredients.[39]

- Pressure cooking – This technique is used extensively for shortening the cooking time for lentils, meat and rice.

Other methods of food preparation include:

- Baking – Baking is seldom used at home. The bread buns or pav used in popular street foods such as vadapav are baked by commercial bakers.

- Microwave –

- Sun drying – Papadum, a popular snack, and related products called papdya and kurdaya, are dried in the sun after rolling out. The dried products keep for many months.[40]

- Fermentation – This is used mainly for making yogurt or home-made butter from cream-enriched milk.[41]

Special dishes

A number of dishes are made for religious occasions, dinner parties or as restaurant items or street food.[42]

Meat and poultry

Meat dishes are prepared in a variety of ways:

- Taambda rassa is a hot spicy goat curry with red gravy from Kolhapur.

- Pandhara rassa is also a goat curry from Kolhapur with white coconut-milk-based gravy.[43]

- Kheema pav minced goat meat usually eaten with bread rolls.

- Popati (पोपटी) – A chicken dish with eggs and val papdi from the Raigad district of the coastal region.

- Malvani chicken

- Varhadi chicken – A hot chicken curry from the Vidarbha region.

- Kombdi vade – A recipe from Konkan region. Deep-fried flatbread made from spicy rice and urid flour served with chicken curry, more specifically with Malvani chicken curry.

- Chicken mirvani (Sangmeshwari curry)

- Chicken haladvani (Sangmeshwari curry)

Seafood dishes

Seafood is a staple for many communities that hail from the Konkan region.[30] Popular dishes include:

Curries and gravies eaten with rice

Various vegetable curries or gravies are eaten with rice, usually at both lunch and dinner. Popular dishes include:

- Amti – Lentil or bean curry, which is made mainly from toor dal or other lentils such as mung beans or chickpeas.[44] In many instances, vegetables are added to the amti preparation. A popular amti recipe has pods of drumsticks added to the toor dal.[21]

- Kadhi – This type of "curry" is made from a combination of buttermilk and chickpea flour (besan).

- Solkadhi – This soup is prepared from coconut milk and kokam, and is a specialty of the cuisine from the coastal region.

- Saar – Thin broth-like soups made from various dals or vegetables.

- Amsulache saar – Made with kokam.[45]

Pickles and condiments

- Chutney and preserves – Popular chutneys and preserves include raw mango chutney, mint, tamarind chutney, cilantro, panchamrit, and mirachicha thecha. Dry chutneys include those based on oil seeds such as flax seed, peanut, sesame, coconut and karale. Chutney based on the skin of roasted vegetables such as bottle gourd is also popular. Most chutnies include green or red chilli pepper for their heat. Garlic may also be added.

- Metkut – A dry preparation based on a blend of dry roasted legumes and spices.[46]

- Lon'ch (pickle)

- Muramba ― Made with unripe mangoes, spices and sugar.

Beverages

A traditional offering (for a guest) used to be water and jaggery. This has been replaced by tea or coffee. These beverages are served with milk and sugar. Occasionally, along with tea leaves, the brew may include spices, freshly grated ginger[47][48] or lemon grass.[49] Coffee is served with milk and/or ground nutmeg.[50] Other beverages include:

- Kairi'ch pa'nh – A raw mango and jaggery-based drink which is popular during early summer,[51][52] served cold.

- Piyush – A shrikhand and buttermilk-based sweet preparation.

- Kokum sarbat – kokum and sugar, served cold.

- Solkadhi

- Masala taak – Spicy buttermilk, served cold.

- Sugar cane juice.

- Banana smoothie – This is consumed with chapatis or puri as part of a meal.

- Masala doodh – Sweet and spicy milk.

- Masala soda – A recently invented sweet and spicy cola.

Sweets and desserts

Desserts are an important part of festival and special occasion food. Typical sweets include lentil and jaggery mix, stuffed flatbread called puran poli, a preparation made from strained yogurt, sugar and spices called shrikhand, a sweet milk preparation made with evaporated milk called basundi, semolina and sugar based kheer and steamed dumplings stuffed with coconut and jaggery called modak. In some instances, the modak is deep-fried instead of steamed.[53][44][54] Traditionally, these desserts were associated with a particular festival. For example, modak is prepared during the Ganpati Festival.

- Puran Poli is one of the most popular sweet items in the Maharashtrian cuisine.[55] It is a buttery flatbread stuffed with jaggery (molasses or gur ), yellow gram (chana) dal, plain flour, cardamom powder and ghee. It is consumed at almost all festivals. Puran Poli is usually served with milk or a sweet-and-sour dal preparation called katachi amti. In rural areas it used to be served with a thin hot sugar syrup called gulawani.[44]

- Modak is a sweet dumpling that is steamed (ukdiche modak)[53][44] or fried. Modak is prepared during the Ganesha Festival around August, when it is often given as an offering to Lord Ganesha, as it is reportedly his favorite sweet. The sweet filling is made up of fresh-grated coconut and jaggery, while the soft shell is made from rice flour, or wheat flour mixed with khava or maida flour. The dumpling can be fried or steamed. The steamed version called ukdiche modak is eaten hot with ghee.

- Chirote[56] is a combination of semolina and plain flour.

- Anarsa is made from soaked powdered rice with jaggery or sugar. The traditional process for creating the anarsa batter takes three days.[44]

- Basundi is a sweetened dense milk dessert.[57]

- Amras is a pulp or thick juice made from mangoes, with a bit of sugar and/or milk.

- Shrikhand is a sweetened yogurt flavoured with saffron, cardamom and charoli nuts. Shrikhand puri is prepared on Gudhipadwa (Marathi new year).[58][59]

- Amrakhand is Shrikhand flavoured with mango, saffron, cardamom and charoli nuts.[58]

- Ladu are a popular snack traditionally prepared for Diwali. Ladus can be based on semolina, gram flour or bundi.

- Pedha are round balls made from a mixture of khoa, sugar and saffron.

- Amba barfi is made from mango pulp.

- Gul Poli is a stuffed wheat-flatbread with gul paste.

- Amba poli or mango poli: Although called poli or flatbread, this is not one. It is more like a pancake. It is made in summer by sun-drying thin spreads of reduced mango-pulp, possibly with sugar added, on flat plates. (Traditionally large leaves were used instead of plates.) It has no grain in it. Since it is sun-dried in harsh summer, it is durable and can be stored for several months.

- Phanas poli (Jackfruit poli) is similar to Amba poli but made with jackfruit pulp instead of mango.

- Ambavadi

- Chikki is a sugar peanut or other nut preparation.

- Narali paak is a sugar and coconut cake.

- Dudhi halwa is a traditional dessert made with dudhi and milk.

Other popular sweets include: kaju katli, gulab jamun, jalebi, various kinds of barfi, and rasmalai.

Street food, restaurant and homemade snacks

In many metropolitan areas, including Mumbai and Pune, fast food is popular. The most-popular forms are bhaji, vada pav, misalpav and pav bhaji. More-traditional dishes are sabudana khichadi, pohe, upma, sheera and panipuri. Most Marathi fast food and snacks are lacto-vegetarian.

Some dishes, including sev bhaji, misal pav and patodi are regional dishes within Maharashtra.

Maharashtrian snacks and street foods are popular throughout the state, but most especially in Mumbai.

- Chivda is spiced flattened rice. It is also known as "Bombay mix" in the UK.

- Pohe is a snack made from flattened rice. It is typically served with tea and is the most likely dish that a Maharashtrian will offer a guest. During arranged marriages, kanda pohe (literal translation, "pohe prepared with onion") is most likely the dish served when the two families meet. It is so common that sometimes arranged marriage itself is referred colloquially as kanda pohay. Other variants include batata pohe (where diced potatoes are used instead of onion shreds). Other famous recipes made with pohe (flattened rice) are dadpe pohe, a mixture of raw pohe with shredded fresh coconut, green chillies, ginger and lemon juice and kachche pohe, raw pohe with minimal embellishments of oil, red chili powder, salt and unsautéed onion shreds.

- Upma, sanja or upeeth is similar to the South Indian upma. It is a thick porridge made from semolina perked up with green chillies, onions and other spices.

- Surali Wadi is a chickpea flour roll with a garnishing of coconut, coriander leaves and mustard.[60]

- Vada pav is a fast food dish consisting of a fried mashed potato dumpling (vada), eaten sandwiched in a wheat bread bun (pav). This is the Indian version of a burger and is almost always accompanied with red chutney made from garlic and fried red and green chillies. Vada pav in its entirety is rarely made at home, mainly because home baking is not common.[61][62]

- Pav bhaji is a fast food dish consisting of a vegetable curry (Marathi: bhaji ) served with a soft bread roll (pav).[63][64]

- Misal Pav is a dish from Kolhapur. It is made from curried sprouted lentils, topped with batata bhaji, pohay, chivda, farsaan, raw chopped onions and tomato. It is sometimes eaten with yogurt. Usually, the misal is served with a wheat-bread bun.[65]

- Thalipeeth is a type of flatbread. It is usually spicy and eaten with curd.[66] It is a popular traditional breakfast that is prepared using bhajani, a mixture of roasted lentils.

- Sabudana Khichadi: Sautéed sabudana (pearls of sago palm), a dish commonly eaten on religious fast days.

- Sabudana vada is a deep-fried snack based on sabudana. It is often served with spicy green chutney and hot chai and is best eaten fresh.

- Khichdi is made of rice and dal with mustard seeds and onions to add flavor.

- Chana daliche dheerde is a savory crepe made with chana dal.

Like most Indian cuisines, Maharashtrian cuisine is laced with lots of fried savories, including:

- Aluchi vadi is prepared from colocasia leaves rolled in chickpea flour, steamed and then pan fried.

- Kothimbirichi vadi is made with cilantro leaves.

- Bhelpuri: Bhelpuri (Marathi भेळ) is a savoury snack, and is also a type of chaat. It is made of puffed rice, chopped vegetables such as tomatoes and onions and a tangy tamarind sauce. Bhelpuri is often associated with Mumbai beaches, such as Girguam or Juhu.[67] Bhelpuri is thought to have originated within the cafes and street-food stalls of Mumbai, and has spread across India where it was modified to suit local food availability. It is also said to be originated from Bhadang (भडंग), a spicy puffed-rice dish from Western Maharashtra. Dry bhel is made from bhadang.

- Sevpuri type of chaat. It originates from Mumbai. In Mumbai, sev puri is strongly associated with street food, but is also served at upscale locations. Supermarkets stock ready-to-eat packets of sev puri and similar snacks like bhelpuri.

- Ragda pattice is a popular Mumbai fast food. This dish is usually served at restaurants that offer Indian fast food along with other dishes. It is a main item on menus of food stalls. This dish has two parts: ragda, a spicy stew based on dry peas and fried potato patties.[68]

- Dahipuri is a form of chaat and from Mumbai. It is served with mini puri shells that are more-popularly recognized from the dish pani puri. Dahi puri and pani puri chaats are often sold from the same vendor.

Special occasions and festivals

Makar Sankrant

This festival falls on January 14 of the Gregorian calendar. Maharashtrians exchange tilgul or sweets made of jaggery and sesame seeds along with the customary salutation, tilgul ghya aani god bola, which means "Accept the tilgul and be friendly." Tilgul Poli or gulpoli are the main sweet preparations. It is a wheat-based flatbread filled with sesame seeds and jaggery.[69][70]

Mahashivratri

Marathi Hindu people fast on this day. Fasting food includes chutney prepared with pulp of the kavath fruit (Limonia).[71]

Holi

As part of Holi, a festival that is celebrated on the full moon evening in the month of Falgun (March or April), a bonfire is lit to symbolize the end of winter and the slaying of a demon in Hindu mythology. People make puran poli as a ritual offering to the holy fire.[54] The day after the bonfire night is called Dhulivandan. Marathi people celebrate with colors on the fifth day after the bonfire on Rangpanchami.[72]

Ganesh Chaturthi

Modak is said to be the favorite food of Ganesh. An offering of twenty-one pieces of this sweet preparation is offered on Ganesh Chaturthi and other minor Ganesh-related events.[73][74]

Diwali

Diwali is one of the most popular Hindu festivals. In Maharashtrian tradition family members have a ritual bath before dawn and then sit down for a breakfast of fried sweets and savory snacks. These sweets and snacks are offered to visitors and exchanged with neighbors. Typical sweet preparations include ladu, anarse, shankarpali and karanjya. Popular savory treats include chakli, shev and chiwda.[75] High in fat and low in moisture, these snacks can be stored at room temperature for many weeks without spoiling.

Champa Sashthi

Many Maharashtrian communities from all social levels observe the Khandoba Festival or Champa Shashthi in the month of Mārgashirsh. Households perform Ghatasthapana of Khandoba during this festival. The sixth day of the festival is called Champa Sashthi. For many people, the Chaturmas period ends on Champa Sashthi. It is customary for many families not to consume onions, garlic and eggplant during the Chaturmas. Following the festival, the consumption of these foods resumes with ritual preparation of vangyache bharit (baingan bharta) with rodga.[76][77]

Traditional wedding menu

The traditional wedding menu among Maharashtrian Hindu communities used to be a lacto-vegetarian fare with mainly multiple courses of rice dishes with different vegetables and dals. Some menus also included a course with puris. In some communities, the first course was plain rice and the second was dal with masala rice.[78]) The main meal typically ended with plain rice and mattha. Some of the most-popular curries to go with this menu and with other festivals were those prepared from taro (Marathi: अलउ) leaves. Buttermilk with spices and coriander leaves, called mattha, is served with the meal. Popular sweets for the wedding menu were shreekhand, boondi ladu and jalebi.[79][80]

Hindu fasting cuisine

Marathi Hindu people fast on days such as Ekadashi, in honour of Lord Vishnu or his Avatars, Chaturthi in honour of Ganesh, Mondays in honour of Shiva, or Saturdays in honour of Maruti or Saturn.[81] Only certain kinds of foods are allowed to be eaten. These include milk and other dairy products (such as yogurt), fruit and Western food items such as sago,[82] potatoes,[83] purple-red sweet potatoes, amaranth seeds, nuts and varyache tandul (shama millet).[84] Popular fasting dishes include Sabudana Khichadi or danyachi amti (peanut soup).[85]

Endnotes

- ↑ Some of the indigenous Marathi communities of North Konkan and Mumbai are Aagri, Koli, Pathare Prabhu, SKPs (Panchkalshi) and (Chaukalshi), CKPs and East Indian Catholic }

- ↑ Fish Koliwada is not part of traditional Maharashtrian cuisine, however, it is an iconic appetizer from Mumbai created by the Singh brothers, Bahadur and Hakam in the 1950s. In 1955, Bahadur Singh along with his brother Hakam Singh folded up their small dhaba near Delhi–Uttar Pradesh highway and moved to Sion in Mumbai where many from his community had already taken shelter after the Partition of India. The brothers started selling the fried fish from a bare-boned makeshift stall. The popularity of their crispy fried-fish led to their first eatery at Sion Koliwada in 1970, aptly named Mini Punjab.

References

Citations

- ↑ Singh, K.S. (2004). Maharashtra (first ed.). Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. p. XLIX. ISBN 81-7991-100-4. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ KHANNA, VIKAS (Dec 1, 2012). My Great Indian Cookbook. Penguin UK,.

- ↑ Khatau, Asha (2004). Epicure S Vegetarian CuisinesJOf India. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan ltd. p. 57. ISBN 81-7991-119-5.

- 1 2 3 Singh, K.S. (2004). People of India: Maharashtra (Vol. 30). Popular Prakashan. p. XLvii.

- ↑ TIWALE, SACHIN (2010). "Foodgrain vs Liquor: Maharashtra under Crisis". Economic and Political Weekly. 45 (22): 19. JSTOR 27807071.

- ↑ Stemler, editors, Jack R. Harlan, Jan M.J. de Wet, Ann B.L. (1976). Origins of African plant domestication. The Hague: Mouton. pp. 409–412. ISBN 978-0202900339.

- ↑ Hawley, edited by John C. (2008). India in Africa, Africa in India : Indian Ocean cosmopolitanisms ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0253219756.

- ↑ Rao, S., Joshi, S., Bhide, P., Puranik, B., & Asawari, K. (2014). Dietary diversification for prevention of anaemia among women of childbearing age from rural India. Public health nutrition, 17(04), 939-947.

- ↑ Khatau, Asha (2003). Epicure's Vegetarian Cuisines of India. Popular Prakashan. p. 57. ISBN 978-8179911198. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- 1 2 Krishnamachari, K.A.V.R., Rao, N.P. and Rao, K.V., 1974. Food and nutritional situation in the drought affected areas of Maharashtra-a survey and recommendations. Indian journal of nutrition and dietetics, 11(1), pp.20-27.

- ↑ Kulshrestha, V.P., 1985. History and ethnobotany of wheat in India. Journal d'agriculture traditionnelle et de botanique appliquée, 32(1), pp.61-71.

- ↑ Rice Bowl: Vegetarian Rice Recipes from India and the World.

- ↑ Singh, K.S. (2004). People of India: Maharashtra (Vol. 30). Popular Prakashan. p. XLviii.

- ↑ Yildiz, edited by Fatih (2010). Development and manufacture of yogurt and other functional dairy products. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4200-8207-4. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ Chapman, Pat (2007). India--food & cooking : the ultimate book on Indian cuisine. London: New Holland. p. 160. ISBN 978-184537-6192. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ Barve, Mangala; Translator: Datar, Snehalata. Annapurna (1 ed.). Mumbai, India: Majestic Prakashan. ISBN 9788174320032. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Singh, K.S. (2004). Maharashtra (first ed.). Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. p. XLVIII. ISBN 81-7991-100-4.

- 1 2 McWilliams, Mark (Editor); Rowe, Caroline (Author) (2014). Food & material culture : proceedings of the oxford symposium on food and cookery. Blackawton, Devon, UK: Prospect books. pp. 268–269. ISBN 9781909248403. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ Singh, G., Kawatra, A. and Sehgal, S., 2001. Nutritional composition of selected green leafy vegetables, herbs and carrots. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 56(4), pp.359-364.

- ↑ Reddy, N.S. and Bhatt, G., 2001. Contents of minerals in green leafy vegetables cultivated in soil fortified with different chemical fertilizers. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 56(1), pp.1-6.

- 1 2 Gupta, S., Lakshmi, A.J. and Prakash, J., 2008. Effect of different blanching treatments on ascorbic acid retention in green leafy vegetables. Nat. Prod. Radiance, 7, pp.111-116.

- ↑ Mane, Asha, et al. "Improvement in nutritional and therapeutic properties of daily meal items through addition of oyster mushroom." Proceedings of 8th International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products (ICMBMP8), New Delhi, India, 19–22 November 2014. Volume I & II. ICAR-Directorate of Mushroom Research, 2014.

- ↑ Bharadwaj, Monisha (2005). The Indian Spice Kitchen (Illustrated ed.). Hippocrene Books. p. 167. ISBN 0-7818-1143-0. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ↑ Bladholm, Linda (2000). The Indian grocery store demystified (1st ed.). Los Angeles: Renaissance Books. pp. 55–63. ISBN 978-1580631433. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Reejhsinghani, Aroona (1975). Delights from Maharashtra (2 ed.). Mumbai, India: Jaico. p. 15. ISBN 9788172245184. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ McWilliams, Mark (Editor); Rowe, Caroline (Author) (2014). Food & material culture : proceedings of the oxford symposium on food and cookery. Blackawton, Devon, UK: Prospect books. p. 267. ISBN 9781909248403. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (September 2007). World and Its People: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 415–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ Christine, Manfield (1999). Spice. London: Viking. p. 22. ISBN 978-0670870851. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ↑ PATOLE, SHAHU (2016). "Why I wrote a book on Dalit food". Express Foodie beta (SEPTEMBER 8). Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- 1 2 Sen, Colleen Taylor (2004). Food culture in India. Westport, Conn.[u.a.]: Greenwood. p. 101. ISBN 0-313-32487-5. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Chapman, Pat (2007). India--food & cooking : the ultimate book on Indian cuisine. London: New Holland. p. 88. ISBN 978-184537-6192. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ Getinet,, A; Sharma, S. M. (1996). Niger, Guizotia Abyssinica (L. F.) Cass By A. Bioversity International. p. 18.

- ↑ Nikam, T.D. and Shitole, M.G., 1993. Regeneration of niger (Guizotia abyssinica Cass.) CV Sahyadri from seedling explants. Plant cell, tissue and organ culture, 32(3), pp.345-349.

- ↑ Arya, A.B., Pradnya, D., Zanvar, V.S. and Devi, R., 2012. Flax Seed Fortification for Value Addition of Chutneys. The Indian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics, 49(2), pp.68-77.

- ↑ Taylor Sen, Colleen (2014). Feasts and Fasts A History of Indian Food. London: Reaktion Books. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-78023-352-9. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Khedkar, R., Shastri, P. and Bawa, A.S., Standardization, Characterization and Shelf Life Studies on Sandge, a Traditional Food Adjunct of Western India. IJEAB: Open Access Bi-Monthly International Journal: Infogain Publication, 1 (Issue-2)

- ↑ Rai, Ranjit (1990). Curry, curry, curry : the heart of Indian cooking. New Delhi, India: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140129939.

- ↑ Dandekar, Hemalata (2004). "Women, Food and the Sustainable Economy: A Simple Relationship". Progressive Plannin. 158 (Winter issue): 41–43. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ Jaffrey, Madhur (2003). Madhur Jaffrey Indian cooking. (1st ed. for North American. ed.). Hauppauge, N.Y.: Barron's. p. 162. ISBN 978-0764156496. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Khedkar, R., Shastri, P. and Bawa, A.S., Standardization, Characterization and Shelf Life Studies on Sandge, a Traditional Food Adjunct of Western India. IJEAB: Open Access Bi-Monthly International Journal: Infogain Publication, 1(Issue-2).

- ↑ Morgan, James LeRoy (2006). Culinary Creation: An Introduction to Foodservice and World Cuisine. Oxford, UK: Butterworth -Henneman. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-7506-7936-7. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Seal, Partho Pratim (2016). How to Succeed in Hotel Management Job Interviews Kindle Edition (1st ed.). Jaico Publishing House;. ISBN 8184957424. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ Wright, Clifford A. (2012). Some like it hot : spicy favorites from the world's hot zones (Uncorr. bound galley. ed.). Boston, Mass.: Harvard Common. ISBN 978-1558322691. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reejhsinghani 1975, p. x.

- ↑ Khatan, Asha. Epicure's Vegetarian Cuisines of India. Popular Prakashan. p. 58. ISBN 81-7991-119-5. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ↑ Renu, K., Pratima, S. and Bawa, A.S., 2016. Standardization, chemical characterization and storage studies on Metkut, a pulse based Indian traditional food adjunct. Food Science Research Journal, 7(1), pp.105-111.

- ↑ Being Marathi. "INDIAN TEA MAKING FULL RECIPE GINGER TEA चहा MONSOON SPECIAL". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "ginger tea recipe". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "Chaitime". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "Vadani kaval gheta". Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ "Flavours of Maharashtra at Renaissance". The Times of India. 12 July 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ "Feed your ‘Desi Mania’ at Nirula's". Fnbnews. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- 1 2 Khanna, Vikas (2013). SAVOUR MUMBAI: A CULINARY JOURNEY THROUGH INDIA's MELTING POT. New Delhi: Westland Limited.

- 1 2 Taylor Sen, Colleen (2014). Feasts and Fasts A History of Indian Food. London: Reaktion Books. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-78023-352-9. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Puran Poli - Lazy 2 Cook, Loves 2 Eat !!!". Lazy 2 Cook, Loves 2 Eat !!!. 2015-04-22. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ↑ "Recipe for Chirote". 22 October 2011.

- ↑ CHOUGULE, VM, BK PAWAR, and DM CHOUDHARI. "Sensory quality of Basundi prepared by using cardamom and saffron." Research Journal of Animal Husbandry and Dairy Science 5.1 (2015).

- 1 2 SENAPATI, A., PANDEY, A., ANN, A., RAJ, A., GUPTA, A., DAS, A.J., RENUKA, B., NEOPANY, B., RAJ, D., ANGCHOK, D. and CHYE, F.Y., 2016. INDIGENOUS FERMENTED FOODS INVOLVING ACID FERMENTATION.

- ↑ Singh, Kumar Suresh. People of India: Maharashtra. Vol. 30. Popular Prakashan, 2004.

- ↑ "Indiaparenting.com - Recipes". www.indiaparenting.com. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ↑ Graves, Helen. "Vada pav sandwich recipe". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Sarma, Ramya. "In Search of Mumbai Vada Pav". The Hindu. The Hindu. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Dalal, Tarla (2010). Mumbai's Roadside Snacks. Mumbai: Sanjay & Company. p. 60. ISBN 978-81-89491-66-6. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Wells, Troth (2006). The world of street food : easy quick meals to cook at home. London: New Internationalist. p. 54. ISBN 978-1904456506.

- ↑ Hingle, R. (2015). Vegan Richa's Indian Kitchen: Traditional and Creative Recipes for the Home Cook. Vegan Heritage Press, LLC. p. pt237. ISBN 978-1-941252-10-9. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ↑ Khatau, Asha (2004). Epicure S Vegetarian Cuisines Of India. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan ltd. p. 63. ISBN 81-7991-119-5.

- ↑ Chapman, Pat (2007). India--food & cooking : the ultimate book on Indian cuisine. London: New Holland. p. 37. ISBN 978-184537-6192. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ Wells, Troth (2006). The world of street food : easy quick meals to cook at home. London: New Internationalist. p. 50. ISBN 1904456502.

- ↑ Naik*, S.N.; Prakash, Karnika (2014). "Bioactive Constituents as a Potential Agent in Sesame for Functional and Nutritional Application". JOURNAL OF BIORESOURCE ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY. 2 (4): 42–60.

- ↑ Sen, Colleen Taylor (2004). Food culture in India. Westport, Conn.[u.a.]: Greenwood. p. 142. ISBN 978-0313324871. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Deshmukh, B. S.; Waghmode, Ahilya (July 2011). "Role of wild edible fruits as a food resource: Traditional knowledge" (PDF). INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES. 2 (7): 919–924.

- ↑ Gupte 1994, p. 90.

- ↑ Zealiot, Eleanor; Berntsen, Maxine (1988). The experience of Hinduism: Essays on religion in Maharashtra. Albany, New York, USA: State University of New York Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-88706-662-3.

- ↑ Ghosh, Shweta (2013). "Eating Spaces, Resisting Creation A study of creation and consumption of travel-based food shows on regional and national television" (PDF). SubVersions. 1 (1): 96. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Edmund W. Lusas; Lloyd W. Rooney (5 June 2001). Snack Foods Processing. CRC Press. pp. 488–. ISBN 978-1-4200-1254-5.

- ↑ Gupte 1994, p. 16.

- ↑ Pillai 1997, p. 192.

- ↑ "Masale bhat". indianrecipedelights.blogspot.com. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ by, SHRIYA. "THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO CKP WEDDINGS: FOOD AND DESSERT". The big fat indian wedding. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ Dalal 2010, p. 6.

- ↑ Arnott, editor Margaret L. (1975). Gastronomy : the anthropology of food and food habitys. The Hague: Mouton. p. 319. ISBN 978-9027977397. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Walker, ed. by Harlan (1997). Food on the move : proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1996, [held in September 1996 at Saint Antony's College, Oxford]. Devon, England: Prospect Books. p. 291. ISBN 978-0907325796. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Dalal 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ Dalal 2010, p. 63.

Bibliography

- Sadhana Ginde

- Reejhsinghani, Aroona (1975). Delights from Maharashtra. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing. ISBN 81-7224-518-1.

- Dalal, Tarla (2010). Faraal Foods for fasting days. Mumbai: Sanjay and Co. ISBN 9789380392028.

- Gupte, B. A. (1994). Hindu Holidays and Ceremonials: With Dissertations on Origin, Folklore and Symbols. Asian Educational Services. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-206-0953-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuisine of Maharashtra. |