Magnetic declination

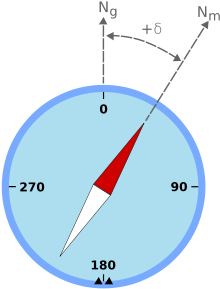

Magnetic declination or variation is the angle on the horizontal plane between magnetic north (the direction the north end of a compass needle points, corresponding to the direction of the Earth's magnetic field lines) and true north (the direction along a meridian towards the geographic North Pole). This angle varies depending on position on the Earth's surface, and changes over time.

Somewhat more formally, Bowditch defines variation as “the angle between the magnetic and geographic meridians at any place, expressed in degrees and minutes east or west to indicate the direction of magnetic north from true north. The angle between magnetic and grid meridians is called grid magnetic angle, grid variation, or grivation.”[1]

By convention, declination is positive when magnetic north is east of true north, and negative when it is to the west. Isogonic lines are lines on the Earth's surface along which the declination has the same constant value, and lines along which the declination is zero are called agonic lines. The lowercase Greek letter δ (delta) is frequently used as the symbol for magnetic declination.

The term magnetic deviation is sometimes used loosely to mean the same as magnetic declination, but more correctly it refers to the error in a compass reading induced by nearby metallic objects, such as iron on board a ship or aircraft.

Magnetic declination should not be confused with magnetic inclination, also known as magnetic dip, which is the angle that the Earth's magnetic field lines make with the downward side of the horizontal plane.

Declination change over time and location

Magnetic declination varies both from place to place and with the passage of time. As a traveller cruises the east coast of the United States, for example, the declination varies from 16 degrees west in Maine, to 6 in Florida, to 0 degrees in Louisiana, to 4 degrees east (in Texas). The declination at London, UK is one degree 7 minutes west (2014), and as the country is quite small that figure is fairly good for the whole of the country. It is reducing, and scientists predict that in about 2050 it will be zero.[2]

In most areas, the spatial variation reflects the irregularities of the flows deep in the Earth; in some areas, deposits of iron ore or magnetite in the Earth's crust may contribute strongly to the declination. Similarly, secular changes to these flows result in slow changes to the field strength and direction at the same point on the Earth.

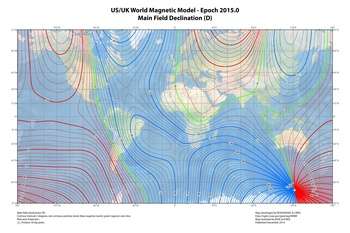

Level curves drawn on a declination map to denote the magnetic declination, described by signed degrees. Each level curve is an isogonic line. |

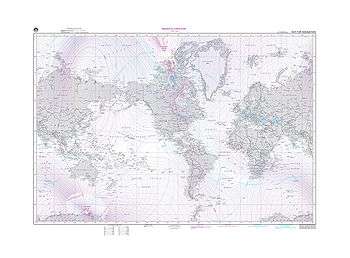

NIMA Magnetic Variation Map 2000 |

The magnetic declination in a given area may (most likely will) change slowly over time, possibly as little as 2–2.5 degrees every hundred years or so, depending upon how far from the magnetic poles it is. For a location closer to the pole like Ivujivik, the declination may change by 1 degree every three years. This may be insignificant to most travellers, but can be important if using magnetic bearings from old charts or metes (directions) in old deeds for locating places with any precision.

As an example of how variation changes over time, see the two charts of the same area (western end of Long Island Sound), below, surveyed 124 years apart. The 1884 chart shows a variation of 8 degrees, 20 minutes West. The 2008 chart shows 13 degrees, 15 minutes West.

.jpg) Western Long Island Sound, 1884 |

.jpg) Western Long Island Sound, 2008 |

|

Determining declination

Direct measurement

The magnetic declination at any particular place can be measured directly by reference to the celestial poles—the points in the heavens around which the stars appear to revolve, which mark the direction of true north and true south. The instrument used to perform this measurement is known as a declinometer.

The approximate position of the north celestial pole is indicated by Polaris (the North Star). In the northern hemisphere, declination can therefore be approximately determined as the difference between the magnetic bearing and a visual bearing on Polaris. Polaris currently traces a circle 0.73° in radius around the north celestial pole, so this technique is accurate to within a degree. At high latitudes a plumb-bob is helpful to sight Polaris against a reference object close to the horizon, from which its bearing can be taken.[3]

Determination from maps and models

A rough estimate of the local declination (within a few degrees) can be determined from a general isogonic chart of the world or a continent, such as those illustrated above. Isogonic lines are also shown on aeronautical and nautical charts.

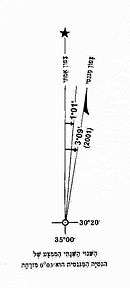

Larger-scale local maps may indicate current local declination, often with the aid of a schematic diagram. Unless the area depicted is very small, declination may vary measurably over the extent of the map, so the data may be referred to a specific location on the map. The current rate and direction of change may also be shown, for example in arcminutes per year. The same diagram may show the angle of grid north (the direction of the map's north-south grid lines), which may differ from true north.

On the topographic maps of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), for example, a diagram shows the relationship between magnetic north in the area concerned (with an arrow marked "MN") and true north (a vertical line with a five-pointed star at its top), with a label near the angle between the MN arrow and the vertical line, stating the size of the declination and of that angle, in degrees, mils, or both.

A prediction of the current magnetic declination for a given location (based on a worldwide empirical model of the deep flows described above) can be obtained online from a web page operated by the National Geophysical Data Center, a division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States.[4] This model is built with all the information available to the map-makers at the start of the five-year period it is prepared for. It reflects a highly predictable rate of change, and is usually more accurate than a map—which is likely months or years out of date—and almost never less accurate.

Software

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) provides source code written in C that is based on the World Magnetic Model (WMM). The source code is free to download and includes a data file updated every five years to account for movement of the magnetic north pole.

Using the declination

Adjustable compasses

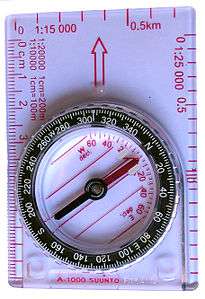

A magnetic compass points to magnetic north, not geographic north. Compasses of the style commonly used for hiking usually include a "baseplate" marked with a bezel that includes a graduated scale of degrees along with the four cardinal directions. Most advanced or costlier compasses include a declination adjustment. Such an adjustment moves the red "orienting arrow" (found on the base of the liquid filled cylinder that contains the needle) relative to the bezel and the baseplate. Either the cylinder has a mark to read against the scale of degrees on the baseplate, or a separate scale displays the current adjustment in degrees (i.e., the angle by which it has turned).

In either case, the underlying concept is that for a declination of 10° W, the red orienting arrow on the cylinder must lie 10° W of 0°/N on the bezel. (Basically, in this case, you are permanently subtracting 10° from your future bearings to compensate for the −10° declination. If your declination was 10°E you would rotate the baseplate's red orienting arrow 10° E of 0°/N to compensate for the +10° declination.) In this sense, it can be said that the compass has been adjusted to indicate true north instead of magnetic north (as long as the compass remains within an area on the same isogonic line).

Non-adjustable compasses

To work with both true and magnetic bearings, the user of a non-adjustable compass needs to make simple calculations that take into account the local magnetic declination. The example on the left shows how you would convert a magnetic bearing (one taken in the field using a non-adjustable compass) to a true bearing (one that you could plot on a map) by adding the magnetic declination. The declination in the example is 14°E (+14°). If, instead, the declination was 14°W (-14°), you would still “add” it to the magnetic bearing to obtain the true bearing: 40°+ (-14°) = 26°.

The opposite procedure is used in converting a true bearing to a magnetic bearing. With a local declination of 14°E, a true bearing (perhaps taken from a map) of 54° is converted to a magnetic bearing (for use in the field) by subtracting the declination: 54° - 14° = 40°. If, instead, the declination was 14°W (-14°), you would still “subtract” it from the true bearing to obtain the magnetic bearing: 26°- (-14°) = 40°.

Navigation

On aircraft or vessels there are three types of bearing: true, magnetic, and compass bearing. Compass error is divided into two parts, namely magnetic variation and magnetic deviation, the latter originating from magnetic properties of the vessel or aircraft. Variation and deviation are signed quantities. As discussed above, positive (easterly) variation indicates that magnetic north is east of geographic north.

Compass, magnetic and true bearings are related by:

The general equation relating compass and true bearings is

Where

is Compass bearing

is Magnetic bearing

is True bearing

is Variation

is compass Deviation

for Westerly Variation and Deviation

for Easterly Variation and Deviation

To calculate true bearing from compass bearing (and known deviation and variation):

- Compass bearing + deviation = magnetic bearing

- Magnetic bearing + variation = true bearing.

To calculate compass bearing from true bearing (and known deviation and variation):

- True bearing − variation = Magnetic bearing

- Magnetic bearing − deviation = Compass bearing.

These rules are often combined with the mnemonic "West is Best, East is least"; that is to say, add W declinations when going True headings to Magnetic Compass, and subtract E ones.

Another simple way to remember which way to apply the correction for Continental USA is:

- For locations east of the agonic line (zero declination), roughly east of the Mississippi: The magnetic bearing is always bigger.

- For locations west of the agonic line (zero declination), roughly west of the Mississippi: The magnetic bearing is always smaller.

Common abbreviations are:

- TC = true course;

- V = variation (of the Earth's magnetic field);

- MC = magnetic course (what the course would be in the absence of local declination);

- D = deviation caused by magnetic material (mostly iron and steel) on the vessel;

- CC = compass course.

Deviation

Magnetic deviation is the angle from a given magnetic bearing to the related bearing mark of the compass. Deviation is positive if a compass bearing mark (e.g., compass north) is right of the related magnetic bearing (e.g., magnetic north) and vice versa. For example, if the boat is aligned to magnetic north and the compass' north mark points 3° more east, deviation is +3°. Deviation varies for every compass in the same location and depends on such factors as the magnetic field of the vessel, wristwatches, etc. The value also varies depending on the orientation of the boat. Magnets and/or iron masses can correct for deviation, so that a particular compass accurately displays magnetic bearings. More commonly, however, a correction card lists errors for the compass, which can then be compensated for arithmetically. Deviation must be added to compass bearing to obtain magnetic bearing.

Air navigation

Magnetic declination has a very important influence on air navigation, since the most simple aircraft navigation instruments are designed to determine headings by locating magnetic north through the use of a compass or similar magnetic device.

Aviation sectionals (maps / charts) and databases used for air navigation are based on true north rather than magnetic north, and the constant and significant slight changes in the actual location of magnetic north and local irregularities in the planet's magnetic field require that charts and databases be updated at least twice each year to reflect the current magnetic variation correction from true north.

For example, as of March 2010, near San Francisco, magnetic north is about 14.3 degrees east of true north, with the difference decreasing by about 6 minutes of arc per year.[5]

When plotting a course, most small aircraft pilots plot a trip using true north on a sectional (map), then convert the true north bearings to magnetic north for in-plane navigation using the magnetic compass. During flight, the pilot derives the correct compass course by adding or subtracting the local variation displayed on a sectional.

Radionavigation aids located on the ground, such as VORs, are also checked and updated to keep them aligned with magnetic north to allow pilots to use their magnetic compasses for accurate and reliable in-plane navigation.

Runways are designated by a number between 01 and 36, which is generally one tenth of the magnetic azimuth of the runway's heading: a runway numbered 09 points east (90°), runway 18 is south (180°), runway 27 points west (270°) and runway 36 points to the north (360° rather than 0°).[6] However, due to magnetic declination, changes in runway designators have to occur at times to keep their designation in line with the runway's magnetic heading. An exception is made for runways within the Northern Domestic Airspace of Canada; these are numbered relative to true north because proximity to the magnetic North Pole makes the magnetic declination large.

GPS systems used for air navigation can use magnetic north or true north. In order to make them more compatible with systems that depend on magnetic north, magnetic north is often chosen, at the pilot's preference. The GPS receiver natively reads in true north, but can elegantly calculate magnetic north based on its true position and data tables; the unit can then calculate the current location and direction of the north magnetic pole and (potentially) any local variations, if the GPS is set to use magnetic compass readings.

See also

Nautical portal

Nautical portal Geomagnetism – Wikipedia book

Geomagnetism – Wikipedia book- Compass survey

- Geomagnetism

- L-shell

- Magnetic inclination

- Pole star

- Shen Kuo

- Voyages of Christopher Columbus

References

- ↑ Bowditch, Nathaniel (2002). American Practical Navigator. Paradise Cay Publications. p. 849. ISBN 9780939837540.

- ↑ "Find the magnetic declination at your location". Magnetic-Declination.com. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ Magnetic declination, what it is , how to compensate.

- ↑ "Estimated Value of Magnetic Declination". Geomagnetism. NOAA National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ According to NOAA Geophysical Data Center on-line model

- ↑ Federal Aviation Administration Aeronautical Information Manual, Chapter 2, Section 3 Airport Marking Aids and Signs part 3b Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

- USGS Geomagnetism Program

- Looks up your IP address location and tells you your declination.

- Online declination calculator at the National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC)

- Online declination and field strength calculator at the NGDC

- Mobile web-app for magnetic declination at the NGDC

- Historical magnetic declination viewer at the NGDC

- Magnetic declination calculator at Natural Resources Canada

- A Google spreadsheet application to bulk calculate magnetic declination

- World Magnetic Model source code download site