Wigwag (railroad)

Wigwag is the nickname given to a type of railroad grade crossing signal once common in North America, named for the pendulum-like motion it used to signal the approach of a train. It is generally credited to Albert Hunt, a mechanical engineer at Southern California's Pacific Electric (PE) interurban streetcar railroad, who invented it in 1909 for safer railroad grade crossings. The term should not be confused with its usage in Britain, where wigwag is generally used to refer to alternate flashing lights, such as those found at modern level crossings.[1]

Rationale

Soon after the advent of the automobile, speeds were increasing and the popularity of enclosed cars made the concept of "stop, look, and listen" at railroad crossings difficult. Fatalities at crossings were increasing. Though the idea of automatic grade crossing protection was not new, no one had invented a fail-safe, universally recognized system. In those days, many crossings were protected by a watchman who warned of an oncoming train by swinging a red lantern in a side-to-side arc, used universally in the U.S. to signify "stop". This motion is still used today by railroad workers to indicate stop per the General Code of Operating Rules (GCOR) Rule 5.3.1. It was presumed that a mechanical device that mimicked that movement would catch the eye of approaching motorists and give an unmistakable warning.

Design

PE's earliest wigwags were gear-driven, but proved difficult to maintain. They were originally built in the railroad's shops. The final design, first installed at a busy crossing near Long Beach, California, in 1914, utilized alternating electromagnets pulling on an iron armature. A red steel target disc, slightly less than two feet in diameter, serving as a pendulum was attached. A red light in the center of the target illuminated, and with each swing of the target a mechanical gong sounded.

The new model, combining sight, motion and sound was dubbed the Magnetic Flagman, with production by the Magnetic Signal Company of Los Angeles, though history is unclear as to exactly when the changeover to Magnetic Signal took place.

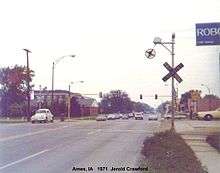

Three mechanically identical versions were produced: The upper-quadrant signal was mounted directly atop a steel pole and waved the target above the motor box. It was intended for use where space was limited. Since the target no longer served as the pendulum, a cast iron counterweight opposite the target was used. Accurate computer-generated animation of this type of signal can be seen in the 2006 theatrical release, Cars. The lower-quadrant version waved the target below the motor box and was intended to be above traffic on a pole mounted cantilever (see above photos). Some railroads, especially in the northwestern US, mounted their lower quadrant versions directly on top of a tall steel pole similar to the upper quadrant signal. They were placed on one side of the road or the other or on an island in the center of the road. They often had crossbucks fastened on top of the motor box. A lower quadrant signal of this kind is seen in the 2004 film Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events.

Though Magnetic Signal manufactured a steel pole and cast-iron base for this purpose (which served as a cabinet for backup batteries and relays), PE often mounted the cantilevers on the wooden poles that supported the overhead catenary providing power for streetcars. This rendered batteries unnecessary, since failure of PE's generators resulted in a shutdown of the railway. This also permitted the relays to be housed in a separate inexpensive cabinet, reducing the cost of the installation.

The third and least common version was a pole mounted lower-quadrant signal suspended above an octagonal steel frame that surrounded the target, presumably to protect both banner and motor box from being damaged by passing vehicles. Dubbed the "peach basket" because of the protective framework, the apparatus was crowned by another visual warning, the traditional X-shaped "RAILROAD CROSSING" sign, or crossbucks. The majority of peach baskets were used by the Union Pacific Railroad. One version of this signal had the lower stripe on the banner replaced with the word stop that was lighted. When the signals was at rest, the words were hidden behind a screen that was painted to look like the missing stripe. They were either mounted on an island in the center of the road or on the side of the road.

The Magnetic Flagman wigwag waves its target with large, black electromagnets pulling against an iron armature. Contacts slide to switch current between the magnets. Each Magnetic Flagman includes a builder's plate (bottom center) detailing patent dates and power requirements.

There were a few different models that were either manufactured by Magnetic Signal or customized by the different railroads. A few examples included two signals on the same pole for different traffic approaches, a circular upper quadrant signal in which the target swung in a circular frame, and three-position signals where the target was hidden behind a sign when the signal was inactive. The Norfolk and Western decided to make a change where the motion-limiting bumpers were placed on the front of the signal instead of inside at the rear. They felt that torque on the armature was reduced. They also had unique lights on their banners.

Any version could be ordered to operate on the railroad signal standard of 8 volts DC (VDC) current or the 600 VDC used to power streetcars and electric locomotives, with little more than a change in the electromagnets. Most, if not all, of the 600 VDC units were used by PE. With the conversion to diesel power after PE sold its passenger operations in 1953, those 600 VDC wigwags were gradually converted to 8 VDC units. There were also some 110 volt AC model Magnetic Flagmen used on several railroads, including Norfolk and Western, Winston-Salem Southbound, and the Milwaukee Road. Since AC power did not generate good torque, a coil cutoff device was installed that utilized all four magnets until full motion of the banner was obtained, then 2 of the magnets went off line and movement was maintained by the remaining two magnets. Other options included a round, counterbalancing "sail" for use in windy areas and which were sometimes painted in the same scheme as the main target, a warning light with adjustable housing, a rare, adjustable turret-style mount for properly aiming the signal if space considerations did not allow for the cantilever to fully extend over the roadway and an "OUT OF ORDER" warning sign that dropped into view if power to the signal was interrupted. The last known example of the turret-mounted wigwag was removed from service in Gardena, California in 2000, while the versions with the warning signs were mostly shipped to Australia. One surviving example is on display at a railway museum in Victoria, in addition to one which has been restored and now operates on the Puffing Billy Railway. An example or two of each signal still survive with collectors.

After these distinctive signals were installed train-versus-car collisions began decreasing at PE grade crossings. They were so common throughout the area that they became near-icons of Southern California motoring. They became popular and Magnetic Signal wigwags began appearing at railroad crossings across the United States (including Alaska on the Copper River & Northwestern Railroad and several Hawaiian railroads), Canada, Mexico, and as far away as Australia. There are also photographs of Magnetic Flagmen in use in Europe.

A ruling by the United States Interstate Commerce Commission mandated a change in the target in the early 1930s, necessitating a change in the paint scheme from solid red to a black cross and border on a white background, but remained otherwise unchanged until another ruling that changed the standard to the alternating red light system in use today. The "black cross on a white background symbol" was adopted for use in the US as the traffic sign warning drivers of an upcoming grade crossing and, in modified form with a yellow background and the cross rotated 45 degrees into an "X," remains in use today. It was also incorporated into the corporate logo of the Santa Fe Railroad. Some railroads, among them the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, instead used a concentric black circle on a white background, resembling a bullseye. This scheme was rare, partly because the L&N used few wigwags.

This, along with other rules pertaining to grade crossing signaling that the wigwag was unable to meet due to its power requirements, rendered it obsolete for new installations in 1949, but grandfathering laws allowed them to remain until upgrades to the crossings they protected were necessary. Magnetic Signal was sold to the Griswold Signal Company of Minneapolis shortly after WWII. Production of new signals continued until 1949, and replacement parts until 1960.

In modern America and elsewhere

Few wigwag signals currently remain in place, though the number dwindles as crossings are upgraded and spare parts become scarce. Once broken down and sold (or given away) as scrap as modern flashers took their place, they are now railroad collectibles, commanding a hefty price and winding up in personal collections of railroad officials. Magnetic Flagman made in Minneapolis, Minnesota after production was moved from Los Angeles are especially rare and are valued by collectors.

According to Federal Railroad Administration data from 2004, there were 215,224 railroad crossings in the U.S., of which 1,098 were listed as having one or more wigwags as their warning device. This is a reduction from 1983 information from the Federal Highway Administration (FRA) that showed 2,618 crossings equipped with wigwags.[2] Of these 1,098 crossings having wigwags, 398 are in California, 117 in Wisconsin, 97 in Illinois, 66 are in Texas and 45 are in Kansas. A total of 44 states have at least one railroad crossing having a wigwag as its warning device.

As of 2013, only one wigwag in the U.S. remains on a main rail line; a Magnetic Flagman (made in Minneapolis) upper-quadrant at a rural crossing in Delhi, Colorado on the BNSF Railway. Until destroyed by a truck in April 2004, a lower-quadrant Magnetic Flagman wigwag protected a private crossing of a BNSF line hidden from public view by a sound barrier in Pittsburg, California. The wigwag, the last "Model 10" in active use, was replaced by standard highway flashers. The Model 10 was distinguished by its short, low-hanging cantilever and use of crossbucks mounted higher than the cantilever. They were almost exclusively used by the Santa Fe, although there were also a few of this model on the Southern Pacific. In 2011, working wigwags were installed at Disney California Adventure Park in Anaheim, California.

A single lower-quadrant wigwag in the industrial city of Vernon, California, protects a crossing on 49th Street with nine separate tracks on the BNSF Harbor Subdivision. A link between downtown Los Angeles and the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, this line currently sees less traffic since the completion of the more direct Alameda Corridor between downtown and the harbor. This project eliminated many at-grade crossings along Alameda Street and a number of Southern Pacific wigwags remaining from the PE era. Those remaining protect crossings of lightly used spur lines primarily in California and Wisconsin, the latter state featuring a different signal produced by Bryant-Zinc purchased by the Railroad Supply Company, which later became the Western Railroad Supply Company (WRRS).

Wigwags manufactured by WRRS and its predecessors were once numerous in the Midwest, with almost every town using them to protect their main crossings. The most common model was called the Autoflag #5. They functioned in much the same way as the Magnetic Flagmen. They utilized alternating electromagnets to swing a shaft with an attached illuminated banner. Bells were not integral to the devices as with the Magnetic Flagmen. They employed standard bells that were used on other types of signals, and mounted either to the mast or to a bracket on the top of the center harp style, as in the Devil's Lake, WI photo. Autoflag #5s were widely used on the C&NW, CB&Q, Illinois Central, Soo Line and the Milwaukee Road. A few were also used on the Louisville & Nashville and the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio as well as other roads in the US and Canada. Most of these wigwags were removed in the 1970-1980s as crossings were updated. They were made in both a lower quadrant style and a center harp style similar to the Magnetic Flagman's peachbasket style. Early on, there were Autoflag #5s that would hold the banner behind a shield much like the Magnetic Flagman disappearing banner-style. These were replaced as time went on with the standard two-position banner that hung vertically when not energized. Several railroad, such as the GM&O and CB&Q, had a second light below the main light on the banner. This served as a second reserve light in case of failure of both bulbs in the main light and as a signal maintainers' warning of a burned out bulb without having to climb up and open the main light to check each bulb. If the secondary light was illuminated, there was an issue with burned out bulbs in the main light.

Wigwags were also manufactured by Union Switch and Signal (US&S). They were primarily used in the northeastern US, with a few in Florida, although the Frisco had some in the Great Plains. An example was also pictured in a review of Hawaiian sugar cane railroads from the 1940s.[3] They were manufactured in both a disappearing banner style in the East and standard two-position in the Great Plains. While there are a few examples in museums, the sole surviving US&S wigwag in service in the US is a two-position style in Joplin, MO on an ex-Frisco industrial spur. It was not destroyed in the May, 2011 Joplin tornado, being a few blocks outside the damage path. These were a bit different in design from the Autoflag #5 and the Magnetic Flagman. The swing of the banner was produced through a drive shaft. Some of them, particularly on the Boston & Maine Railroad, had chase lights mounted above the banner that simulated the movement of the banner. The last one of this type with the chase lights was removed in 1985 and US&S wigwags were thought to have disappeared from the USA until the discovery of the specimen in Joplin. There are a number of US&S wigwags that have been preserved and restored by museums.

US&S and WRRS wigwags were also used by the CPR on its Canadian lines. The last ones in use on the CPR are believed to have been removed in Chatham, Ontario in the mid-1980s. Two wig-wags remain in service in Canada, located on the CN CASO sub near Tilbury, Ontario. Both are WRRS Autoflag #5s with disappearing banners. Disappearing banners were the only style of wigwag approved for use in Canada. They were slated to be removed in early 2009, although they are still in place as of November, 2009. In 2011, the CASO sub was abandoned & the wigwags will be removed. There are several US&S wigwags employed today in Chile, but little literature about this style has survived. Several movie clips of the wigwags in this area were made in 2009.

The wigwags at the crossing that mark the location of the western terminus of the BNSF in Richmond, California became pawns in a fight over local control in 2003. The two upper-quadrant wigwags are the last of their kind paired together in active use, and are on land that the BNSF plans to develop. The BNSF is also bowing to pressure from the state's transportation authority to upgrade the crossing with modern signals. Richmond is trying to preserve the crossing with historical designation and other planning tools. According to information recently posted at Dan's Wigwag Site (see below), the crossing will be updated with gates, modern flashers and bells. In an unusual compromise, the wigwags will remain as non-operative decorations at the crossing, once the modern gates, red lights and bells are put in place. In the interest of safety, signs will be posted at the wigwags stating that the signals are non-operational. The ability to be activated by trains will be retained, but only for special events.[4] In 2011, a water main break caused a catastrophic ground collapse under one of the Point Richmond wig-wags and it was removed for safekeeping while the area was being repaired.

On the episode of American Restoration aired on April 16, 2013, a pair of WRRS Autoflag #5 wigwag signals were restored for the Nevada Northern Railway Museum in Ely, Nevada.

See also

References

- Dan's Wigwag Site. This is the preeminent website on the Magnetic Flagman wigwag and was the primary source of reference for this entry. Accessed April 25, 2006

- ↑ Traffic Light System Auto Mate Systems

- ↑ US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration (September 1986). Railroad-Highway Grade Crossing Handbook; second edition, FHWA-TS-86-215 (PDF). p. 30. Retrieved 2006-04-25.

- ↑ Hawaiian Railway Album World War II Photos Vol 3 -- Plantation Ry's on Oahu

- ↑ Todd, Gail (17 April 2008). "Point Richmond: A tunnel separating two worlds". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wigwags. |

- Orange Empire Railway Museum. A link to the Orange Empire Railway Museum of Perris, California whose impressive collection includes a number of working wigwags on display.

- City of Vernon. Article about the Vernon wigwag on the City of Vernon's own website.

- Link to information about the Richmond wigwags.

- San Francisco Bay Crossings.com article.

- Wig Wag Archive Via Google Maps