Madrid

| Madrid | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||||||

From upper left: Gran Vía street, Plaza Mayor, view of business districts of AZCA and CTBA, Puerta de Alcalá, and view of Royal Palace and Almudena Cathedral. | |||||||

| |||||||

|

Motto: "Fui sobre agua edificada, mis muros de fuego son. Esta es mi insignia y blasón" ("On water I was built, my walls are made of fire. This is my ensign and escutcheon") | |||||||

Madrid  Madrid Location of Madrid within Spain / Community of Madrid | |||||||

| Coordinates: 40°23′N 3°43′W / 40.383°N 3.717°WCoordinates: 40°23′N 3°43′W / 40.383°N 3.717°W | |||||||

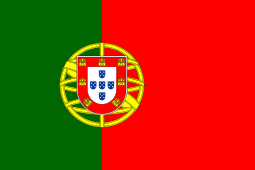

| Sovereign State |

| ||||||

| Autonomous community |

| ||||||

| Comarcas | Metropolitan Area and Corredor del Henares | ||||||

| Founded | 9th century[1] | ||||||

| Government | |||||||

| • Body | Ayuntamiento de Madrid | ||||||

| • Mayor | Manuela Carmena (Ahora Madrid) | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| • Municipality | 604.3 km2 (233.3 sq mi) | ||||||

| Elevation | 667 m (2,188 ft) | ||||||

| Population (2015[2]) | |||||||

| • Municipality | 3,141,991 | ||||||

| • Rank | 1st | ||||||

| • Density | 5,390/km2 (14,000/sq mi) | ||||||

| • Urban | 6,240,000 (2,016)[3] | ||||||

| • Metro | 6,529,700 (2,014)[4] | ||||||

| Demonym(s) |

Madridian, Madrilenian, Madrilene, Cat madrileño, -ña; matritense; gato (es) | ||||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||||||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||||

| Postal code | 28001–28080 | ||||||

| Area code(s) | +34 (ES) + 91 (M) | ||||||

| Patron saints |

Isidore the Laborer Virgin of Almudena | ||||||

| Website | www.madrid.es | ||||||

Madrid (/məˈdrɪd/, Spanish: [maˈðɾið], locally [maˈðɾi(θ)]) is the capital city of the Kingdom of Spain and the largest municipality in both the Community of Madrid and Spain as a whole. The city has almost 3.2 million[2] inhabitants with a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.5 million. It is the third-largest city in the European Union (EU) after London and Berlin, and its metropolitan area is the third-largest in the EU after those of London and Paris.[5][6][7][8] The municipality itself covers an area of 604.3 km2 (233.3 sq mi).[9]

Madrid lies on the River Manzanares in the centre of both the country and the Community of Madrid (which comprises the city of Madrid, its conurbation and extended suburbs and villages); this community is bordered by the autonomous communities of Castile and León and Castile-La Mancha. As the capital city of Spain, seat of government, and residence of the Spanish monarch, Madrid is also the political, economic and cultural centre of the country.[10] The current mayor is Manuela Carmena from Ahora Madrid.

The Madrid urban agglomeration has the third-largest GDP[11] in the European Union and its influences in politics, education, entertainment, environment, media, fashion, science, culture, and the arts all contribute to its status as one of the world's major global cities.[12][13] Madrid is home to two world-famous football clubs, Real Madrid and Atlético de Madrid. Due to its economic output, high standard of living, and market size, Madrid is considered the major financial centre of Southern Europe[14][15] and the Iberian Peninsula; it hosts the head offices of the vast majority of major Spanish companies, such as Telefónica, Iberia, and Repsol. Madrid is the 17th most liveable city in the world according to Monocle magazine, in its 2014 index.[16][17]

Madrid houses the headquarters of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), belonging to the United Nations Organization (UN), the Ibero-American General Secretariat (SEGIB), the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI), and the Public Interest Oversight Board (PIOB). It also hosts major international regulators and promoters of the Spanish language: the Standing Committee of the Association of Spanish Language Academies, headquarters of the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE), the Cervantes Institute and the Foundation of Urgent Spanish (Fundéu BBVA). Madrid organises fairs such as FITUR,[18] ARCO,[19] SIMO TCI[20] and the Cibeles Madrid Fashion Week.[21]

While Madrid possesses modern infrastructure, it has preserved the look and feel of many of its historic neighbourhoods and streets. Its landmarks include the Royal Palace of Madrid; the Royal Theatre with its restored 1850 Opera House; the Buen Retiro Park, founded in 1631; the 19th-century National Library building (founded in 1712) containing some of Spain's historical archives; a large number of national museums,[22] and the Golden Triangle of Art, located along the Paseo del Prado and comprising three art museums: Prado Museum, the Reina Sofía Museum, a museum of modern art, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which completes the shortcomings of the other two museums.[23] Cibeles Palace and Fountain have become one of the monument symbols of the city.[24][25]

Etymology

The first documented reference of the city originates in Andalusan times as the Arabic مجريط Majrīṭ (AFI [madʒriːtˁ]), which was retained in Medieval Spanish as Magerit ([madʒeˈɾit]). A wider number of theories have been formulated on possible earlier origins.

According to legend, Madrid was founded by Ocno Bianor (son of King Tyrrhenius of Tuscany and Mantua) and was named "Metragirta" or "Mantua Carpetana". Others contend that the original name of the city was "Ursaria" ("land of bears" in Latin), because of the many bears that were to be found in the nearby forests, which, together with the strawberry tree (Spanish madroño), have been the emblem of the city since the Middle Ages.[26]

The most ancient recorded name of the city "Magerit" (for *Materit or *Mageterit?) comes from the name of a fortress built on the Manzanares River in the 9th century AD, and means "Place of abundant water".[27] If the form is correct, it could be a Celtic place-name from ritu- 'ford' (Old Welsh rit, Welsh rhyd, Old Breton rit, Old Northern French roy) and a first element, that is not clearly identified *mageto derivation of magos 'field, plain' (Old Irish mag 'field', Breton ma 'place'), or matu 'bear', that could explain the Latin translation Ursalia.[28]

Nevertheless, it is also speculated that the origin of the current name of the city comes from the 2nd century BC. The Roman Empire established a settlement on the banks of the Manzanares river. The name of this first village was "Matrice" (a reference to the river that crossed the settlement). Following the invasions carried out by the Germanic Sueves and Vandals, as well as the Sarmatic Alans during the 5th century AD, the Roman Empire no longer had the military presence required to defend its territories on the Iberian Peninsula, and as a consequence, these territories were soon occupied by the Vandals, who were in turn dispelled by the Visigoths, who then ruled Hispania in the name of the Roman emperor, also taking control of "Matrice". In the 8th century, the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula saw the name changed to "Mayrit", from the Arabic term ميرا Mayra (referencing water as a 'tree' or 'giver of life') and the Ibero-Roman suffix it that means 'place'. The modern "Madrid" evolved from the Mozarabic "Matrit", which is still in the Madrilenian gentilic.[29]

History

Middle Ages

Although the site of modern-day Madrid has been occupied since prehistoric times,[30][31][32] and there are archaeological remains of Carpetani settlement,[30] Roman villas,[33] a Visigoth basilica near the church of Santa María de la Almudena[26][34] and three Visigoth necropoleis near Casa de Campo, Tetúan and Vicálvaro,[35] the first historical document about the existence of an established settlement in Madrid dates from the Muslim age. At the second half of the 9th century,[36] Emir Muhammad I of Córdoba built a fortress on a headland near the river Manzanares,[37] as one of the many fortresses he ordered to be built on the border between Al-Andalus and the kingdoms of León and Castile, with the objective of protecting Toledo from the Christian invasions and also as a starting point for Muslim offensives. After the disintegration of the Caliphate of Córdoba, Madrid was integrated in the Taifa of Toledo.

With the surrender of Toledo to Alfonso VI of León and Castile, the city was conquered by Christians in 1085, and it was integrated into the kingdom of Castile as a property of the Crown.[38] Christians replaced Muslims in the occupation of the centre of the city, while Muslims and Jews settled in the suburbs. The city was thriving and was given the title of Villa, whose administrative district extended from the Jarama in the east to the river Guadarrama in the west. The government of the town was vested to the neighbouring of Madrid since 1346, when king Alfonso XI of Castile implements the regiment, for which only the local oligarchy was taking sides in city decisions.[39] Since 1188, Madrid won the right to be a city with representation in the courts of Castile. In 1202, King Alfonso VIII of Castile gave Madrid its first charter to regulate the municipal council,[40] which was expanded in 1222 by Ferdinand III of Castile.

In 1309, the Courts of Castile were joined in Madrid for the first time under Ferdinand IV of Castile, and later in 1329, 1339, 1391, 1393, 1419 and twice in 1435. Since the unification of the kingdoms of Spain under a common Crown, the Courts were convened in Madrid more often.

Modern Age

During the revolt of the Comuneros, led by Juan de Padilla, Madrid joined the revolt against Emperor Charles V of Germany and I of Spain, but after defeat at the Battle of Villalar, Madrid was besieged and occupied by the royal troops. However, Charles I was generous to the town and gave it the titles of Coronada (Crowned) and Imperial. When Francis I of France was captured at the battle of Pavia, he was imprisoned in Madrid. And in the village is dated the Treaty of Madrid of 1526 (later denounced by the French) that resolved their situation.[41]

The number of urban inhabitants grew from 4,060 in the year 1530 to 37,500 in the year 1594. The poor population of the court was composed of ex-soldiers, foreigners, rogues and Ruanes, dissatisfied with the lack of food and high prices. In June 1561, when the town had 30,000 inhabitants, Philip II of Spain moved his court from Valladolid to Madrid, installing it in the old castle.[43] Thanks to this, the city of Madrid became the political centre of the monarchy, being the capital of Spain except for a short period between 1601 and 1606 (Philip III of Spain's government), in which the Court returned to Valladolid. This fact was decisive for the evolution of the city and influenced its fate.

During the reign of Philip III and Philip IV of Spain, Madrid saw a period of exceptional cultural brilliance, with the presence of geniuses such as Miguel de Cervantes, Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Quevedo and Lope de Vega.[44]

The death of Charles II of Spain resulted in the War of the Spanish succession. The city supported the claim of Philip of Anjou as Philip V. While the city was occupied in 1706 by a Portuguese army, who proclaimed king the Archduke Charles of Austria under the name of Charles III, and again in 1710, remained loyal to Philip V.

Philip V built the Royal Palace, the Royal Tapestry Factory and the main Royal Academies.[45] But the most important Bourbon was King Charles III of Spain, who was known as "the best mayor of Madrid". Charles III took upon himself the feat of transforming Madrid into a capital worthy of this category. He ordered the construction of sewers, street lighting, cemeteries outside the city, and many monuments (Puerta de Alcalá, Cibeles Fountain), and cultural institutions (El Prado Museum, Royal Botanic Gardens, Royal Observatory, etc.). Despite being known as one of the greatest benefactors of Madrid, his beginnings were not entirely peaceful, as in 1766 he had to overcome the Esquilache Riots, a traditionalist revolt instigated by the nobility and clergy against his reformist intentions, demanding the repeal of the clothing decree ordering the shortening of the layers and the prohibition of the use of hats that hide the face, with the aim of reducing crime in the city.[46]

The reign of Charles IV of Spain is not very meaningful to Madrid, except for the presence of Goya in the Court, who portrayed the popular and courtly life of the city.

From the 19th century to present day

On 27 October 1807, Charles IV and Napoleon I signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau, which allowed the passage of French troops through Spanish territory to join the Spanish troops and invade Portugal, which had refused to obey the order of international blockade against England. As this was happening, there was the Mutiny of Aranjuez (17 March 1808), by which the crown prince, Ferdinand VII, replaced his father as king. However, when Ferdinand VII returned to Madrid, the city was already occupied by Joachim-Napoléon Murat, so that both the king and his father were virtually prisoners of the French army. Napoleon, taking advantage of the weakness of the Spanish Bourbons, forced both, first the father then the son, to join him in Bayonne, where Ferdinand arrived on 20 April.

In the absence of the two kings, the situation became more and more tense in the capital. On 2 May, a crowd began to gather at the Royal Palace. The crowd saw the French soldiers pulled out of the palace to the royal family members who were still in the palace. Immediately, the crowd launched an assault on the floats. The fight lasted hours and spread throughout Madrid. Subsequent repression was brutal. In the Paseo del Prado and in the fields of La Moncloa hundreds of patriots were shot due to Murat's order against "Spanish all carrying arms". Paintings such as The Third of May 1808 by Goya reflect the repression that ended the popular uprising on 2 May.[47]

The Peninsular War against Napoleon, despite the last absolutist claims during the reign of Ferdinand VII, gave birth to a new country with a liberal and bourgeois character, open to influences coming from the rest of Europe. Madrid, the capital of Spain, experienced like no other city the changes caused by this opening and filled with theatres, cafés and newspapers. Madrid was frequently altered by revolutionary outbreaks and pronouncements, such as Vicálvaro 1854, led by General Leopoldo O'Donnell and initiating the progressive biennium. However, in the early 20th century Madrid looked more like a small town than a modern city. During the first third of the 20th century the population nearly doubled, reaching more than 950,000 inhabitants. New suburbs such as Las Ventas, Tetuán and El Carmen became the homes of the influx of workers, while Ensanche became a middle-class neighbourhood of Madrid.[48]

The Spanish Constitution of 1931 was the first legislated on the state capital, setting it explicitly in Madrid.

Madrid was one of the most heavily affected cities of Spain in the Civil War (1936–1939). The city was a stronghold of the Republicans from July 1936. Its western suburbs were the scene of an all-out battle in November 1936 and it was during the Civil War that Madrid became the first European city to be bombed by aeroplanes (Japan was the first to bomb civilians in world history, at Shanghai in 1932) specifically targeting civilians in the history of warfare. (See Siege of Madrid (1936–39)).[49]

During the economic boom in Spain from 1959 to 1973, the city experienced unprecedented, extraordinary development in terms of population and wealth, becoming the largest GDP city in Spain, and ranking third in Western Europe. The municipality was extended, annexing neighbouring council districts, to achieve the present extension of 607 km2 (234.36 sq mi). The south of Madrid became very industrialised, and there were massive migrations from rural areas of Spain into the city. Madrid's newly built north-western districts became the home of the new thriving middle class that appeared as result of the 1960s Spanish economic boom, while the south-eastern periphery became an extensive working-class settlement, which was the base for an active cultural and political reform.[49]

After the death of Franco and the start of the democratic regime, the 1978 constitution confirmed Madrid as the capital of Spain. In 1979, the first municipal elections brought Madrid's first democratically elected mayor since the Second Republic. Madrid was the scene of some of the most important events of the time, such as the mass demonstrations of support for democracy after the foiled coup, 23-F, on 23 February 1981. The first democratic mayors belonged to the leftist parties (Enrique Tierno Galván, Juan Barranco Gallardo), turning the city after more conservative positions (Agustín Rodríguez Sahagún, José María Álvarez del Manzano, Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón and Ana Botella). Benefiting from increasing prosperity in the 1980s and 1990s, the capital city of Spain has consolidated its position as an important economic, cultural, industrial, educational, and technological centre on the European continent.[49]

Geography

Climate

The Madrid region has an inland Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa)[50] bordering on a semi-arid climate (BSk),[51] with cool winters due to its altitude of 667 m (2,188 ft) above sea level, including sporadic snowfalls and minimum temperatures sometimes below freezing. Summers are hot, in the warmest month – July -average temperatures during the day ranging from 32 to 33 °C (90 to 91 °F) depending on location, with maximums commonly climbing over 35 °C (95 °F) during heat waves. Due to Madrid's altitude and dry climate, diurnal ranges are often significant during the summer. The highest recorded temperature was on 24 July 1995, at 42.2 °C (108.0 °F), and the lowest recorded temperature was on 16 January 1945 at −10.1 °C (13.8 °F). Although these records were registered at the airport, not at the city.[52] Precipitation is concentrated in the autumn and spring, and, together with Athens which has similar annual precipitation, is the driest capital in Europe. It is particularly sparse during the summer, taking the form of about two showers and/or thunderstorms a month.

| Climate data for Madrid (667 m), Buen Retiro Park in the city centre (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.2 (72) |

28.2 (82.8) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.0 (50) |

19.9 (67.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.3 (43.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

22.2 (72) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

15.0 (59) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.1 (61) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33 (1.3) |

35 (1.38) |

25 (0.98) |

45 (1.77) |

51 (2.01) |

21 (0.83) |

12 (0.47) |

10 (0.39) |

22 (0.87) |

60 (2.36) |

58 (2.28) |

51 (2.01) |

421 (16.57) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 148 | 157 | 214 | 231 | 272 | 310 | 359 | 335 | 261 | 198 | 157 | 124 | 2,769 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[53][54][55][56] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Madrid-Barajas Airport (609 m), in north east Madrid (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

32.8 (91) |

27.9 (82.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

21.1 (70) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.5 (41.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.9 (57) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.7 (47.7) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 29 (1.14) |

32 (1.26) |

22 (0.87) |

38 (1.5) |

44 (1.73) |

22 (0.87) |

9 (0.35) |

10 (0.39) |

24 (0.94) |

51 (2.01) |

49 (1.93) |

42 (1.65) |

371 (14.61) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 55 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 144 | 168 | 224 | 226 | 258 | 310 | 354 | 329 | 258 | 199 | 151 | 128 | 2,749 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[53] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Madrid-Cuatro Vientos Airport, 8 km (4.97 mi) from the city centre (altitude: 690 metres (2,260 feet), satellite view) (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

28.9 (84) |

32.8 (91) |

32.2 (90) |

27.3 (81.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.2 (72) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.7 (44.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.6 (34.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34 (1.34) |

35 (1.38) |

25 (0.98) |

43 (1.69) |

50 (1.97) |

25 (0.98) |

12 (0.47) |

11 (0.43) |

24 (0.94) |

60 (2.36) |

57 (2.24) |

53 (2.09) |

428 (16.85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 158 | 173 | 221 | 238 | 280 | 316 | 364 | 335 | 250 | 203 | 161 | 135 | 2,840 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[57] | |||||||||||||

Water supply

Madrid derives almost 73.5 percent of its water supply from dams and reservoirs built on the Lozoya River, such as the El Atazar Dam, which was built in 1972 and inaugurated by Francisco Franco.[58] This water supply is managed by Canal de Isabel II, a public entity created in 1851. It is responsible for the supply, depurating waste water and the conservation of all the Comunidad de Madrid region natural water resources.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1897 | 510,616 | — |

| 1900 | 540,109 | +5.8% |

| 1910 | 556,958 | +3.1% |

| 1920 | 728,937 | +30.9% |

| 1930 | 863,958 | +18.5% |

| 1940 | 1,096,466 | +26.9% |

| 1950 | 1,527,894 | +39.3% |

| 1960 | 2,177,123 | +42.5% |

| 1970 | 3,120,941 | +43.4% |

| 1980 | 3,158,818 | +1.2% |

| 1991 | 2,909,792 | −7.9% |

| 2001 | 2,938,723 | +1.0% |

| 2011 | 3,198,645 | +8.8% |

| 2014 | 3,165,235 | −1.0% |

| 2015 | 3,141,991 | −0.7% |

| Source: Alterations to the municipalities in the Population Censuses since 1842, Instituto Nacional de Estadistica | ||

| Largest groups of foreign residents | |

| Nationality | Population (2015) |

|---|---|

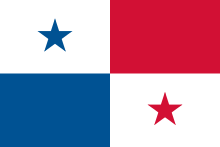

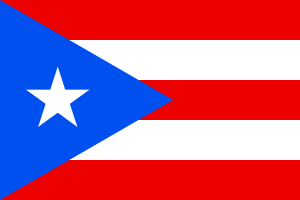

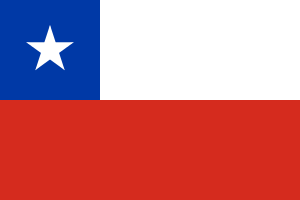

| 46,410 | |

| 32,174 | |

| 29,867 | |

| 21,137 | |

| 19,654 | |

| 18,606 | |

| 17,617 | |

| 16,802 | |

| 16,523 | |

| 14,134 | |

| 10,522 | |

| 9,534 | |

| 8,420 | |

| 5,658 | |

| 3,393 | |

The population of Madrid has overall increased since the city became the capital of Spain in the mid-16th century, and has stabilised at approximately 3 million since the 1970s.

From 1970 until the mid-1990s, the population dropped. This phenomenon, which also affected other European cities, was caused in part by the growth of satellite suburbs at the expense of the downtown region within the city proper. This also occurred during a period of slowed growth in the European economy.

The demographic boom accelerated in the late 1990s and early first decade of the 21st century due to immigration in parallel with a surge in Spanish economic growth. According to census data, the population of the city grew by 271,856 between 2001 and 2005.

Immigration

As the capital city of Spain, the city has attracted many immigrants from around the world. In 2015, about 89.8% of the inhabitants were Spanish, while people of other origins, including immigrants from Latin America, Europe, Asia, North Africa and West Africa, represented 11.2% of the population.

The ten largest immigrant groups include: Ecuadorian: 104,184, Romanian: 52,875, Bolivian: 44,044, Colombian: 35,971, Peruvian: 35,083, Chinese: 34,666, Moroccan: 32,498, Dominican: 19,602, Brazilian: 14,583, and Paraguayan: 14,308.[59] There were 2,476 Japanese citizens registered with the Japanese embassy in Madrid in 1993.[60] There are also important communities of Filipinos, Equatorial Guineans, Uruguayans, Bulgarians, Greeks, Indians, Italians, Argentines, Senegalese and Poles.[59]

Districts that host the largest number of immigrants are Usera (28.37%), Centro (16.87%), Carabanchel (22.72%) and Tetuán (21.54%). Districts that host the smallest number are Fuencarral-El Pardo (9.27%), Retiro (9.64%) and Chamartín (11.74%). Many members of Madrid's Japanese community, particularly those with children, live in Majadahonda, Mirasierra, The Vaguada, and other areas in northwest Madrid, in proximity to the Japanese international school. Central Madrid attracted many Japanese company employees without children due to its proximity to places of employment.[60]

Religion

The traditional religion in Madrid is Roman Catholic. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Madrid. In a 2011 survey conducted by InfoCatólica, 57.1% of Madrid residents of all ages identified themselves as Catholic.[61]

Government

The City Council consists of 57 members, one of them being the mayor. The mayor presides over the RKO.

The Plenary of the Council is the body of political representation of the citizens in the municipal government. Some of its attributions are: fiscal matters, the election and deposition of the mayor, the approval and modification of decrees and regulations, the approval of budgets, the agreements related to the limits and alteration of the municipal term, the services management, the participation in supramunicipal organisations, etc.[62] Nowadays, mayoral team consists of the mayor, the deputy mayor and 8 delegates; all of them form The Board of Delegates (the Municipal Executive Committee).[63]

Madrid has tended to be a stronghold of the People's Party (PP, right-wing political party), which has controlled the city's mayoralty since 1989. In the 2007 regional and local elections, the People's Party obtained 34 seats, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE, left political party) obtained 18 and United Left (IU, left political party) obtained 5. In the 2015 elections, however, the PP was the party with the most votes but failed to gain a majority with Ahora Madrid the runner-up. Manuela Carmena, mayoral candidate for Ahora Madrid, was proclaimed mayor after a coalition pact between her party and the PSOE.

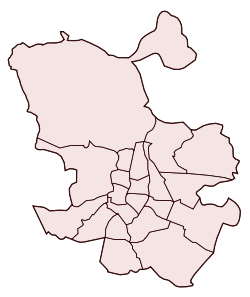

Districts

Madrid is administratively divided into 21 districts, which are further subdivided into 128 wards (barrios)

| Madrid districts. The numbers correspond with the list in the left |

- Centro: Palacio, Embajadores, Cortes, Justicia, Universidad, Sol.

- Arganzuela: Imperial, Acacias, La Chopera, Legazpi, Delicias, Palos de Moguer, Atocha.

- Retiro: Pacífico, Adelfas, Estrella, Ibiza, Jerónimos, Niño Jesús.

- Salamanca: Recoletos, Goya, Fuente del Berro, Guindalera, Lista, Castellana.

- Chamartín: El Viso, Prosperidad, Ciudad Jardín, Hispanoamérica, Nueva España, Castilla.

- Tetuán: Bellas Vistas, Cuatro Caminos, Castillejos, Almenara, Valdeacederas, Berruguete.

- Chamberí: Gaztambide, Arapiles, Trafalgar, Almagro, Vallehermoso, Ríos Rosas.

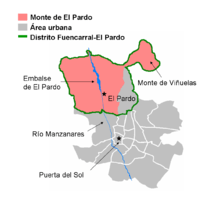

- Fuencarral-El Pardo: El Pardo, Fuentelarreina, Peñagrande, Barrio del Pilar, La Paz, Valverde, Mirasierra, El Goloso.

- Moncloa-Aravaca: Casa de Campo, Argüelles, Ciudad Universitaria, Valdezarza, Valdemarín, El Plantío, Aravaca.

- Latina: Los Cármenes, Puerta del Ángel, Lucero, Aluche, Las Águilas, Campamento, Cuatro Vientos.

- Carabanchel: Comillas, Opañel, San Isidro, Vista Alegre, Puerta Bonita, Buenavista, Abrantes.

- Usera: Orcasitas, Orcasur, San Fermín, Almendrales, Moscardó, Zofío, Pradolongo.

- Puente de Vallecas: Entrevías, San Diego, Palomeras Bajas, Palomeras Sureste, Portazgo, Numancia.

- Moratalaz: Pavones, Horcajo, Marroquina, Media Legua, Fontarrón, Vinateros.

- Ciudad Lineal: Ventas, Pueblo Nuevo, Quintana, La Concepción, San Pascual, San Juan Bautista, Colina, Atalaya, Costillares.

- Hortaleza: Palomas, Valdefuentes, Canillas, Pinar del Rey, Apóstol Santiago, Piovera.

- Villaverde: San Andrés, San Cristóbal, Butarque, Los Rosales, Los Ángeles.

- Villa de Vallecas: Casco Histórico de Vallecas, Santa Eugenia.

- Vicálvaro: Casco Histórico de Vicálvaro, Ambroz.

- San Blas: Simancas, Hellín, Amposta, Arcos, Rosas, Rejas, Canillejas, Salvador.

- Barajas: Alameda de Osuna, Aeropuerto, Casco Histórico de Barajas, Timón, Corralejos.

Metropolitan area

The Madrid metropolitan area comprises the city of Madrid and forty surrounding municipalities. It has a population of slightly more than 6.271 million people[64] and covers an area of 4,609.7 square kilometres (1,780 sq mi). It is the largest metropolitan area in Spain and the third largest in the European Union.[5][6][7][8]

As with many metropolitan areas of similar size, two distinct zones of urbanisation can be distinguished:

- Inner ring (primera corona): Alcorcón, Leganés, Getafe, Móstoles, Fuenlabrada, Coslada, Alcobendas, Pozuelo de Alarcón, San Fernando de Henares

- Outer ring (segunda corona): Villaviciosa de Odón, Parla, Pinto, Valdemoro, Rivas-Vaciamadrid, Torrejón de Ardoz, Alcalá de Henares, San Sebastián de los Reyes, Tres Cantos, Las Rozas de Madrid, Majadahonda, Boadilla del Monte

The largest suburbs are to the South, and in general along the main routes leading out of Madrid.

Submetropolitan areas inside Madrid metropolitan area:

| Submetropolitan area | Area (km²) |

Population (pop.) |

Density (pop./km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid – Majadahonda | 996.1 | 3,580,828 | 3,595.0 |

| Móstoles – Alcorcón | 315.1 | 430,349 | 1,365.6 |

| Fuenlabrada – Leganés – Getafe – Parla – Pinto – Valdemoro | 931.7 | 822,806 | 883.1 |

| Alcobendas | 266.4 | 205,905 | 772.9 |

| Arganda del Rey – Rivas-Vaciamadrid | 343.6 | 115,344 | 335.7 |

| Alcalá de Henares – Torrejón de Ardoz | 514.6 | 360,380 | 700.3 |

| Colmenar Viejo – Tres Cantos | 419.1 | 104,650 | 249.7 |

| Collado Villalba | 823.1 | 222,769 | 270.6 |

| Madrid metropolitan area | 4,609.7 | 5,843,031 | 1,267.6 |

Cityscape

Architecture

Very little medieval architecture is preserved in Madrid, mostly in the Almendra central, including the San Nicolás and San Pedro el Viejo church towers, the church of St. Jerome, and the Bishop's Chapel. Nor has Madrid retained much Renaissance architecture, other than the Bridge of Segovia and the Convent of Las Descalzas Reales.

_08.jpg)

Many of the historic buildings of Madrid date from the Spanish Golden Age, which coincided with the Habsburgs reign (1516–1700). Philip II moved his court to Madrid in 1561 and transformed the town into a capital city.[65] These reforms were embodied in the Plaza Mayor, characterised by its symmetry and austerity, as well as the new Alcázar, which would become the second most impressive royal palace of the kingdom. The material used during the Habsburg era was mostly brick, and the humble façades contrast with the elaborate interiors. Notable buildings include the Prison of the Court, the Palace of the Councils, the Royal Convent of La Encarnación, and the Buen Retiro Palace. The Imperial College church model dome was imitated in all of Spain. Pedro de Ribera introduced Churrigueresque architecture to Madrid; the Cuartel del Conde-Duque, the church of Montserrat, and the Bridge of Toledo are among the best examples.

The reign of the Bourbons during the eighteenth century marked a new era in the city. Philip V tried to complete King Philip II's vision of urbanisation of Madrid. Philip V built a palace in line with French taste, as well as other buildings such as St. Michael's Basilica and the Church of Santa Bárbara. King Charles III beautified the city and endeavoured to convert Madrid into one of the great European capitals. He pushed forward the construction of the Prado Museum (originally intended as a Natural Science Museum), the Puerta de Alcalá, the Royal Observatory, the Basilica of San Francisco el Grande, the Casa de Correos in Puerta del Sol, the Real Casa de la Aduana, and the General Hospital (which now houses the Reina Sofia Museum and Royal Conservatory of Music). The Paseo del Prado, surrounded by gardens and decorated with neoclassical statues, is an example of urban planning. The Duke of Berwick ordered the construction of the Liria Palace.

_44.jpg)

During the early 19th century, the Peninsular War, the loss of viceroyalties in the Americas, and continuing coups limited the city's architectural development (Royal Theatre, the National Library of Spain, the Palace of the Senate, and the Congress). The Segovia Viaduct linked the Royal Alcázar to the southern part of town.

From the mid-19th century until the Civil War, Madrid modernised and built new neighbourhoods and monuments. The expansion of Madrid developed under the Plan Castro, resulting in the neighbourhoods of Salamanca, Argüelles, and Chamberí. Arturo Soria conceived the linear city and built the first few kilometres of the road that bears his name, which embodies the idea. The Gran Vía was built using different styles that evolved over time: French style, eclectic, art deco, and expressionist. Antonio Palacios built a series of buildings inspired by the Viennese Secession, such as the Palace of Communication, the Fine Arts Circle of Madrid (Círculo de Bellas Artes), and the Río de La Plata Bank (Instituto Cervantes). Other notable buildings include the Bank of Spain, the neo-Gothic Almudena Cathedral, Atocha Station, and the Catalan art-nouveau Palace of Longoria. Las Ventas Bullring was built, as the Market of San Miguel (Cast-Iron style).

_48.jpg)

The Civil War severely damaged the city. Subsequently, the old town and the Ensanche were destroyed, and numerous blocks of flats were built. Examples of post-war architecture include the Spanish Air Force headquarters and the skyscrapers of Plaza de España, at the time (the 1950s) the highest in Europe.

With the advent of Spanish economic development, skyscrapers, such as Torre Picasso, Torres Blancas and Torre BBVA, and the Gate of Europe, appeared in the late 20th century in the city. During the decade of the 2000s, the four tallest skyscrapers in Spain were built and together form the Cuatro Torres Business Area. Madrid-Barajas Airport Terminal 4 was inaugurated in 2006 and won several architectural awards. Terminal 4 is one of the world's largest terminal areas and features glass panes and domes in the roof, which allow natural light to pass through.

Urban sculpture

The streets of Madrid are a veritable museum of outdoor sculpture. The Museum of Outdoor Sculpture, located in the Paseo de la Castellana, is dedicated to abstract works, among which is the Sirena Varada (Strander Mermaid) by Eduardo Chillida.

Since the 18th century, the Paseo del Prado has been decorated with an iconographic program with classical monumental fountains: the Fuente de la Alcachofa (Fountain of the Artichoke), the Cuatro Fuentes (Four Fountains), the Fuente de Neptuno (Fountain of Neptune), the Fuente de Apolo (Fountain of Apollo), and the Fuente de Cibeles (Fountain of Cybele, also known as Fountain of Cibeles), all designed by Ventura Rodríguez.

The equestrian sculptures are particularly important, starting chronologically with two designed in the 17th century: the statue of Philip III, in the Plaza Mayor by Giambologna, and the statue of Philip IV, in the Plaza de Oriente (undoubtedly the most important statue of Madrid, projected by Velázquez and built by Pietro Tacca with scientific advice of Galileo Galilei).

Many areas of the Buen Retiro Park (Parque del Retiro) are really sculptural scenography: among them are The Fallen Angel by Ricardo Bellver and the Monument to Alfonso XII, designed by José Grases Riera.

In another vein are the neon advertising signs, some of which have acquired a historic range and are legally protected, such as Schweppes in Plaza de Callao or Tío Pepe in the Puerta del Sol, recently retired from its location for the restoration of the building.

_06.jpg) Fountain of Neptune (Ventura Rodríguez)

Fountain of Neptune (Ventura Rodríguez) Fountain of Cybele (Ventura Rodríguez)

Fountain of Cybele (Ventura Rodríguez) Monument to Alfonso XII (José Grasés Riera)

Monument to Alfonso XII (José Grasés Riera)_01.jpg) Strander Mermaid (Eduardo Chillida)

Strander Mermaid (Eduardo Chillida)

_06.jpg) Philip IV (Pietro Tacca)

Philip IV (Pietro Tacca)

Cervantes Monument at Plaza de España (Madrid)

Cervantes Monument at Plaza de España (Madrid)

_01.jpg) Monument to Christopher Columbus (Arturo Mélida, Jerónimo Suñol)

Monument to Christopher Columbus (Arturo Mélida, Jerónimo Suñol)

Environment

Madrid is the European city with the highest number of trees and green surface per inhabitant and it has the second highest number of aligned trees in the world, with 248,000 units, only exceeded by Tokyo. Madrid's citizens have access to a green area within a 15-minute walk. Since 1997, green areas have increased by 16%. At present, 8.2% of Madrid's grounds are green areas, meaning that there are 16 m2 (172 sq ft) of green area per inhabitant, far exceeding the 10 m2 (108 sq ft) per inhabitant recommended by the World Health Organization.

_01.jpg)

Buen Retiro Park (Parque del Buen Retiro, or simply Parque del Retiro), formerly the grounds of the palace built for Philip IV of Spain, is Madrid's most popular park and the largest park in central Madrid. Its area is more than 1.4 km2 (0.5 sq mi) (350 acres) and it is located very close to the Puerta de Alcalá and not far from the Prado Museum. The park is entirely surrounded by the present-day city. Its lake in the middle once staged mini naval sham battles to amuse royalty; these days the more tranquil pastime of pleasure boating is popular. Inspired by London's Crystal Palace, the Palacio de Cristal can be found at the south-eastern end of the park.

In the Buen Retiro Park is also the Forest of the Departed (Bosque de los Ausentes), a memorial monument to commemorate the 191 victims of the 11 March 2004 Madrid attacks.

Atocha Railway Station (Estación de Atocha) is the city's first and most central station, and is also home to a 4,000-square-metre (43,056-square-foot) indoor garden, with more than 500 species of plant life and ponds with turtles and goldfish in.

Casa de Campo is an enormous urban parkland to the west of the city, the largest in Spain and Madrid's main green lung. Its area is more than 1,700 hectares (6.6 sq mi). It is home to a fairground, the Madrid Zoo, an amusement park, the Parque de Atracciones de Madrid, and an outdoor municipal pool, to enjoy a bird's eye view of the park and city take a cable car trip above the tree tops. Casa de Campo's vegetation is one of its most important features. There are, in fact, three different ecosystems: oak, pine and river groves. The oak is the dominant tree species in the area and, although many of them are over 100 years old and reach a great height, they are also present in the form of chaparral and bushes. The pine-forest ecosystem boasts a large number of trees that have adapted perfectly to the light, dry conditions in the park. In addition, mushrooms often emerge after the first rains of autumn. Finally, the river groves, or riparian forests, are made up of various, mainly deciduous, species that grow in wetter areas. Examples include poplars, willows and alder trees. As regards fauna, this green space is home to approximately 133 vertebrate species.

The Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid (Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid) is an 8-hectare botanical garden located in the Plaza de Murillo, next to the Prado Museum. It was an 18th-century creation by Carlos III and it was used as a base for the plant species being collected across the globe. There is an important research facility that started life as a base to develop herbal remedies and to house the species collected from the new-world trips, today it is dedicated to maintaining Europe's ecosystem.

The Royal Palace (Palacio Real) is surrounded by three green areas. In front of the palace, are the gardens of the Plaza de Oriente; to the north, the gardens of Sabatini and to the west up to the Manzanares River, the famous Campo del Moro. Campo del Moro gardens has a surface area of 20 hectares and is a scenic garden with an unusual layout filled with foliage and an air of English romanticism. The Sabatini Gardens have a formal Neoclassic style, consisting of well-trimmed hedges, in symmetric geometrical patterns, adorned with a pool, statues and fountains, with trees also planted in a symmetrical geometric shape. Plaza de Oriente can distinguish three main plots: the Central Gardens, the Cabo Noval Gardens and the Lepanto Gardens. The Central Gardens are arranged around the central monument to Philip IV, in a grid, following the barroque model garden. They consist of seven flowerbeds, each packed with box hedges, forms of cypress, yew and magnolia of small size, and flower plantations, temporary. These are bounded on either side by rows of statues paths, popularly known as the Gothic kings, and mark the dividing line between the main body of the plaza and the Cabo Noval Gardens at north, and the Lepanto Gardens at south.

Mount of El Pardo (Monte de El Pardo) is a mediterranean forest inside the city of Madrid. It is one of the best preserved Mediterranean Forests in Europe. The European Union has designated the Monte de El Pardo as a Special Protection Area for bird-life. This meadow, which has been used as hunting grounds by the royalty given the variety of game animals that have inhabited it since the Middle Ages, is home to 120 flora species and 200 vertebrae species. Rabbits, red partridges, wild cats, stags, deer and wild boars live among ilexes, cork oaks, ash trees, black poplars, oaks, junipers and rockroses. Monte del Pardo is part of the Regional Park of the High Basin of the Manzanares, spreading out from the Guadarrama Mountains range to the centre of Madrid, and protected by strong legal regulations. Just before crossing the city, the River Manzanares forms a valley composed by sandy elements and detritus from the mountain range.

Soto de Viñuelas, also known as Mount Viñuelas, is a meadow-oak forest north of the city of Madrid and east of the Monte de El Pardo. It is a fenced property of about 3,000 hectares, which includes important ecological values, landscape and art. Soto de Viñuelas is part of the Regional Park of the High Basin of the Manzanares, a nature reserve which is recognised as a biosphere reserve by UNESCO, where it has been classified as Area B, the legal instrument that allows agricultural land use. Soto de Viñuelas has also received the statement of Special Protection Area for Birds.

El Capricho is a 14-hectare garden located in the area of Barajas district. It dates back to 1784. The art of landscaping in El Capricho is displayed in three different styles of classical gardenscapes: the "parterre" or French garden, English landscaping and the Italian giardino.

Madrid Río (Madrid River) is a linear park that runs along the bank of the Manzanares River, in the middle of Madrid. It is an area of parkland 10 kilometres (6 miles) long and covers 649 hectares in six districts: Moncloa-Aravaca, Centro, Arganzuela, Latina, Carabanchel and Usera. It is a large area of environmental, sporting, leisure and cultural interest. Madrid Río provides a link with other green spaces in the city such as Casa de Campo and the Linear Park of the Manzanares River. The main landscaped area in Madrid Río is the Arganzuela Park, covering 23 hectares where pedestrian and cycling routes cover the whole park. The Madrid Río cycling network covers some 30 km (19 mi) and is linked to other bike routes. To the north, Madrid Rio connects to the Senda Real, the Green Ring for Cyclists and the E 7 (GR 10) trail, which goes as far as the Sierra de Guadarrama mountain range. To the south, Madrid Río provides access to the Enrique Tierno Galván Park and the Linear Park of the Manzanares River, an extensive green zone running parallel to the river as far as Getafe. As well as the cycle routes there are 42 km (26 mi) of paths for walkers and runners. In the Salón de Pinos, a 6-kilometre long tree-lined promenade, there are circuits for aerobic and anaerobic exercise, while near the Puente de Praga bridge there is a tennis court and seven tennis courts.

The theme park Faunia is a natural history museum and zoo combined, aimed at being fun and educational for children. It comprises eight eco-systems from tropical rain forests to polar regions, and contains over 1,500 animals, some of which roam freely within.

Economy

_02.jpg)

After it became the capital of Spain in the 16th century, Madrid was more a centre of consumption than of production or trade. Economic activity was largely devoted to supplying the city’s own rapidly growing population, including the royal household and national government, and to such trades as banking and publishing.

A large industrial sector did not develop until the 20th century, but thereafter industry greatly expanded and diversified, making Madrid the second industrial city in Spain. However, the economy of the city is now becoming more and more dominated by the service sector.

Madrid is the 5th most important leading Center of Commerce in Europe (after London, Paris, Frankfurt and Amsterdam) and ranks 11th in the world.[14]

Economic history

As the capital city of the Spanish Empire from 1561, Madrid's population grew rapidly. Administration, banking, and small-scale manufacturing centred on the royal court were among the main activities, but the city was more a locus of consumption than production or trade, geographically isolated as it was before the coming of the railways.

Industry started to develop on a large scale only in the 20th century,[66] but then grew rapidly, especially during the "Spanish miracle" period around the 1960s. The economy of the city was then centred on diverse manufacturing industries such as those related to motor vehicles, aircraft, chemicals, electronic devices, pharmaceuticals, processed food, printed materials, and leather goods.[67] Since the restoration of democracy in the late 1970s, the city has continued to expand. Its economy is now among the most dynamic and diverse in the European Union.[68]

Present-day economy

As the national capital, Madrid concentrates activities directly connected with power (central and regional government, headquarters of Spanish companies, regional HQ of multinationals, financial institutions) and with knowledge and technological innovation (research centres and universities). It is one of Europe's largest financial centres and the largest in Spain.[69] The city has 17 universities and over 30 research centres.[69]:52 It is the third metropolis in the EU by population, and the fourth by gross internal product.[69]:69 Leading employers include Telefónica, Iberia, Prosegur, BBVA, Urbaser, Dragados, and FCC.[69]:569

The comunidad de Madrid, containing the city and surrounding areas, had a GDP of €203,626M in 2015, equating to a GDP per capita of €31,812.[70] In 2011 the city itself had a GDP per capita 74% above the national average and 70% above that of the 27 European Union member states, although 11% behind the average of the top 10 cities of the EU.[69]:237–239 Although housing just over 50% of the region's's population, the city generates 65.9% of its GDP.[69]:51 Following the recession commencing 2007/8, recovery was under way by 2014, with forecast growth rates for the city of 1.4% in 2014, 2.7% in 2015 and 2.8% in 2016.[71]:10

The economy of Madrid has become based increasingly on the service sector. In 2011 services accounted for 85.9% of value added, while industry contributed 7.9% and construction 6.1%.[69]:51 Nevertheless, Madrid continues to hold the position of Spain's second industrial centre after Barcelona, specialising particularly in high-technology production. Following the recession, services and industry were forecast to return to growth in 2014, and construction in 2015.[71]:32

Standard of living

Mean household income and spending are 12% above the Spanish average.[69]:537, 553 The proportion classified as "at risk of poverty" in 2010 was 15.6%, up from 13.0% in 2006 but less than the average for Spain of 21.8%. The proportion classified as affluent was 43.3%, much higher than Spain overall (28.6%).[69]:540–3

Consumption by Madrid residents has been affected by job losses and by austerity measures, including a rise in sales tax from 8% to 21% in 2012.[72]

Although residential property prices have fallen by 39% since 2007, the average price of dwelling space was €2,375.6 per sq. m. in early 2014,[71]:70 and is shown as second only to London in a list of 22 European cities.[73]

Employment

_05.jpg)

Participation in the labour force was 1,638,200 in 2011, or 79.0%. The employed workforce comprised 49% women in 2011 (Spain, 45%).[69]:98 41% of economically active people are university graduates, against 24% for Spain as a whole.[69]:103

In 2011, the unemployment rate was 15.8%, remaining lower than in Spain as a whole. Among those aged 16–24, the unemployment rate was 39.6%.[69]:97, 100 Unemployment reached a peak of 19.1% in 2013,[71]:17 but with the start of an economic recovery in 2014, employment started to increase.[74] Employment continues to shift further towards the service sector, with 86% of all jobs in this sector by 2011, against 74% in all of Spain.[69]:117

Services

The share of services in the city’s economy is 86%. Services to business, transport & communications, property & financial together account for 52% of total value added.[69]:51 The types of services that are now expanding are mainly those that facilitate movement of capital, information, goods and persons, and "advanced business services" such as research and development (R&D), information technology, and technical accountancy.[69]:242–3

Banks based in Madrid carry out 72% of the banking activity in Spain.[69]:474 The Spanish central bank, Bank of Spain, has existed in Madrid since 1782. Stocks & shares, bond markets, insurance, and pension funds are other important forms of financial institution in the city.

Madrid is an important centre for trade fairs, many of them coordinated by IFEMA, the Trade Fair Institution of Madrid.[69]:351–2 The public sector employs 18.1% of all employees.[69]:630 Madrid attracts about 8M tourists annually from other parts of Spain and from all over the world, exceeding even Barcelona.[69]:81[69]:362, 374[71]:44 Spending by tourists in Madrid was estimated (2011) at €9,546.5M, or 7.7% of the city’s GDP.[69]:375

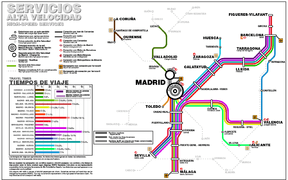

The construction of transport infrastructure has been vital to maintain the economic position of Madrid. Travel to work and other local journeys use a high-capacity metropolitan road network and a well-used public transport system.[69]:62–4 In terms of longer-distance transport, Madrid is the central node of the system of autovías and of the high-speed rail network (AVE), which has brought major cities such as Seville and Barcelona within 2.5 hours travel time.[69]:72–75 Also important to the city's economy is Madrid-Barajas Airport, the fourth largest airport in Europe.[69]:76–78 Madrid’s central location makes it a major logistical base.[69]:79–80

Industry

As an industrial centre Madrid retains its advantages in infrastructure, as a transport hub, and as the location of headquarters of many companies. Industries based on advanced technology are acquiring much more importance here than in the rest of Spain.[69]:271 Industry contributed 7.5% to Madrid's value-added in 2010.[69]:265 However, industry has slowly declined within the city boundaries as more industry has moved outward to the periphery. Industrial Gross Value Added grew by 4.3% in the period 2003–2005, but decreased by 10% during 2008–2010.[69]:271, 274 The leading industries were: paper, printing & publishing, 28.8%; energy & mining, 19.7%; vehicles & transport equipment, 12.9%; electrical and electronic, 10.3%; foodstuffs, 9.6%; clothing, footwear & textiles, 8.3%; chemical, 7.9%; industrial machinery, 7.3%.[69]:266

Construction

The construction sector, contributing 6.5% to the city’s economy in 2010,[69]:265 was a growing sector before the recession, aided by a large transport and infrastructure program. More recently the construction sector has fallen away and earned 8% less in 2009 than it had been in 2000.[69]:242–3 The decrease was particularly marked in the residential sector, where prices dropped by 25%–27% from 2007 to 2012/13[69]:202, 212 and the number of sales fell by 57%.[69]:216

International rankings

A recent study placed Madrid 7th among 36 cities as an attractive base for business.[75] It was placed third in terms of availability of office space, and fifth for easy of access to markets, availability of qualified staff, mobility within the city, and quality of life. Its less favourable characteristics were seen as pollution, languages spoken, and political environment. Another ranking of European cities placed Madrid 5th among 25 cities (behind Berlin, London, Paris and Frankfurt), being rated favourably on economic factors and the labour market, and on transport and communication.[76]

Art and culture

Museums and art centres

Madrid is considered one of the top European destinations concerning art museums. Best known is the Golden Triangle of Art, located along the Paseo del Prado and comprising three museums. The most famous one is the Prado Museum, known for such highlights as Diego Velázquez's Las Meninas and Francisco de Goya's La maja vestida and La maja desnuda. The other two museums are the Thyssen Bornemisza Museum, established from a mixed private collection, and the Reina Sofía Museum, where Pablo Picasso's Guernica hangs, returned to Spain from New York after more than two decades.

The Prado Museum (Museo del Prado) is a museum and art gallery that features one of the world's finest collections of European art, from the 12th century to the early 19th century, based on the former Spanish Royal Collection. The collection currently comprises around 7,600 paintings, 1,000 sculptures, 4,800 prints and 8,200 drawings, in addition to a large number of works of art and historic documents. El Prado is one of the most visited museums in the world, and it is considered to be among the greatest museums of art. It has the best collection of artworks by Goya, Velázquez, El Greco, Rubens, Titian, Hieronymus Bosch, José de Ribera, and Patinir as well as works by Rogier van der Weyden, Raphael Sanzio, Tintoretto, Veronese, Caravaggio, Van Dyck, Albrecht Dürer, Claude Lorrain, Murillo, and Zurbarán, among others. Among the most famous paintings in this museum are Las Meninas',' The Immaculate Conception, and The Judgement of Paris.

The Reina Sofía National Art Museum (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, abbreviated as MNCARS) is Spain's national museum of 20th-century art. The museum is mainly dedicated to Spanish art. Highlights of the museum include excellent collections of Spain's greatest 20th-century masters, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Juan Gris, and Julio González. Certainly the most famous masterpiece in the museum is Picasso's painting Guernica. The Reina Sofía also hosts a free-access library specialising in art, with a collection of over 100,000 books, over 3,500 sound recordings, and almost 1,000 videos.[77]

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza) is an art museum that fills the historical gaps in its counterparts' collections: in the Prado's case, this includes Italian primitives and works from the English, Dutch, and German schools, while in the case of the Reina Sofía, the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, once the second largest private collection in the world after the British Royal Collection,[78] includes Impressionists, Expressionists, and European and American paintings from the second half of the 20th century, with over 1,600 paintings.[79]

The Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando) currently functions as a museum and gallery that houses a fine art collection of paintings from the 15th to 20th centuries, including works by Giovanni Bellini, Correggio, Rubens, Zurbarán, Murillo, Goya, Juan Gris, and Pablo Serrano. The academy is also the headquarters of the Madrid Academy of Art. Francisco Goya was once one of the academy's directors, and its alumni include Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Antonio López García, Juan Luna, and Fernando Botero.[80][81]

The Royal Palace of Madrid (Palacio Real de Madrid) is the official residence of Felipe VI of Spain, but he uses it only for official acts. It is a baroque palace full of artworks and is one of the largest European royal palaces, characterised by its luxurious rooms and its rich collections of armours and weapons, pharmaceuticals, silverware, watches, paintings, tapestries, and the most comprehensive collection of Stradivarius in the world[82]

The National Archaeological Museum (Museo Arqueológico Nacional) collection includes, among others, Pre-historic, Celtic, Iberian, Greek and Roman antiquities, and medieval (Visigothic, Muslim and Christian) objects. Highlights include a replica of the Altamira cave (the first cave in which prehistoric cave paintings were discovered), Lady of Elx (an enigmatic polychrome stone bust), Lady of Baza (a famous example of Iberian sculpture), Biche of Balazote (an Iberian sculpture), and Treasure of Guarrazar (a treasure that represents the best surviving group of early medieval Christian votive offerings and the high point of Visigothic goldsmith's work).[83]

The Museum of the Americas (Museo de América) is a national museum that holds artistic, archaeological, and ethnographic collections from the American continent, ranging from the Paleolithic period to the present day. The permanent exhibit is divided into five major themed areas: an awareness of America, the reality of America, society, religion, and communication.[84]

The National Museum of Natural Sciences (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales) is Spain's national museum of natural history. The research departments of the museum are biodiversity and evolutionary biology, evolutionary ecology, paleobiology, vulcanology, and geology.[85]

The Naval Museum (Museo Naval) is managed by the Ministry of Defense. The museum's mission is to acquire, preserve, investigate, report, and display for study, education, and contemplation parts, sets, and collections of historical, artistic, scientific, and technical works related to naval activity in order to disseminate Spanish maritime history; to help illustrate, highlight, and preserve their traditions; and promote national maritime awareness.[86]

The Convent of Las Descalzas Reales (Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales) resides in the former palace of King Charles I of Spain and Isabella of Portugal. Their daughter, Joan of Austria, founded this convent of nuns of the Poor Clare order in 1559. Throughout the remainder of the 16th century and into the 17th century, the convent attracted young widowed or spinster noblewomen. Each woman brought with her a dowry. The riches quickly piled up, and the convent became one of the richest convents in all of Europe. It has many works of Renaissance and Baroque art, including a recumbent Christ by Gaspar Becerra, a staircase whose paintings were painted by an unknown artist (perhaps Velázquez) and that are considered masterpieces of Spanish Illusionistic painting, and Brussels tapestries inspired by paintings of Rubens.[87]

The Museum of Lázaro Galdiano (Museo de Lázaro Galdiano) houses an encyclopaedic collection specialising in decorative arts. Apart from paintings and sculptures, it displays 10th-century Byzantine enamel; Arab and Byzantine ivory chests; Hellenistic, Roman, medieval, renaissance, baroque, and romantic jewellery; Pisanello and Pompeo Leoni medals; Spanish and Italian ceramics; Italian and Arab clothes; and a collection of weapons; including the sword of Pope Innocent VIII.[88]

The National Museum of Decorative Arts (Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas) is one of the oldest museums in the city and illustrates the evolution of the so-called "minor arts" (furniture, ceramics and glass, textile, etc.). Its 60 rooms display 15,000 of the institute's approximately 40,000 total.[89]

The National Museum of Romanticism (Museo Nacional de Romanticismo) contains a large collection of artefacts and art, focusing on daily life and customs of the 19th century, with special attention to the aesthetics of Romanticism.[90]

The Museum Cerralbo (Museo Cerralbo) houses a private collection of ancient works of art, artefact,s and other antiquities collected by Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa, 17th Marquis of Cerralbo.[91]

The National Museum of Anthropology (Museo Nacional de Antropología) provides an overview of different cultures, with objects and human remains from around the world, highlighting a Guanche mummy from Tenerife.[92]

The Sorolla Museum (Museo Sorolla) is located in the building in which the Valencian Impressionist painter had his home and workshop. The collection includes, in addition to numerous works by Joaquín Sorolla, a large number of objects that the artist possessed, including sculptures by Auguste Rodin.[93]

CaixaForum Madrid is a post-modern art gallery in the centre of Madrid. It is sponsored by the Catalan-Balearic bank La Caixa and located next to the Salón del Prado. Although the CaixaForum is a modern building, it also exhibits retrospectives of artists from earlier time periods and has evolved into one of the most-visited museums in Madrid. It was constructed by the Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron from 2001 to 2007, who took an unused industrial building and hollowed it out at the base and inside and then added additional floors encased with rusted steel. Next to the gallery is an art installation by French botanist Patrick Blanc of green plants growing on the wall of the neighbouring house. The red of the top floors with the green of the wall next to it form a contrast. The green is in reflection of the neighbouring Royal Botanical Garden.[94]

Major cultural centres organise parallel cultural events housed in unique buildings:

_06.jpg)

Centrocentro is an exhibition space in Cibeles Palace, formerly the Palace of Communications and now the City Hall. Two social areas have been set up and offer catalogues and publications about current exhibitions and cultural events along the Art Walk. Near these social areas are two large street maps showing the 59 institutions, monuments and buildings of special interest that make the Art Walk such a diverse experience.

The Fine Arts Circle (Círculo de Bellas Artes), built by Antonio Palacios, is one of Madrid's oldest arts centres and one of the most important private cultural centres in Europe. It is a multidisciplinary centre with activities ranging from visual art to literature, science to philosophy, film and to the performing arts. Nowadays it hosts exhibitions, shows, film screenings, conferences and workshops; its radio programming and magazine Minerva play an important part in the country's cultural life.

Matadero Madrid, literally "Madrid Abattoir", is a complex situated by the river Manzanares whose buildings are an architectural ensemble devoted to performance arts, managed and programmed by the Teatro Español (Madrid). Matadero is a flexible area that allows the autonomous operation of three interconnected spaces: a theatre café, which accommodates small-scale shows; a large stage, for all sorts of genres and more experimental options; and a third building for dressing rooms and areas for training, debate, analysis and rehearsing new productions.

Conde Duque cultural centre has expanded the amount of space dedicated to culture and art. The new installations now accommodate a theatre, an exhibition hall and an auditorium with a year-round program.

Other art galleries and museums in Madrid include:

_07.jpg)

Lady of Elche (National Archaeological Museum)

Lady of Elche (National Archaeological Museum)_03.jpg)

Museum of Madrid History

Museum of Madrid History

Landmarks

_27.jpg)

In the year 2006, Madrid was the fourth most-visited city in Europe and the first in Spain, with almost seven million tourists.[98] It is also the seat of the World Tourism Organization and the International Tourism Fair – FITUR.

Most of the tourist attractions of Madrid are in the old town and the Ensanche, corresponding with the districts of Centro, Salamanca, Chamberí, Retiro, and Arganzuela. The nerve centre of the city is the Puerta del Sol, the starting point for the numbering of all city streets and all the country's highways.

The Calle de Alcalá or Alcalá Street leads from the Puerta del Sol from the NE of the city. From the street you get from Plaza de Cibeles. Subsequently, the street reaches the "Plaza de la Independencia", which includes the Puerta de Alcalá and an entrance to the Buen Retiro Park.

The Calle Mayor leads to Plaza Mayor continuing for the so-called Madrid de los Austrias, in reference to the Dynasty of Habsburg – finally reaching Calle de Bailén, near the Cathedral of the Almudena and the church of San Francisco el Grande.

The Calle del Arenal comes to Royal Theatre in Plaza de la Ópera, continuing through Plaza de Oriente, where the Royal Palace is. From there, the Calle Bailen leads to the Plaza de España and the Temple of Debod, an Egyptian temple moved stone by stone to Spain in gratitude for their help in the construction of the Aswan Dam. Also in this square is the start of the Gran Vía street.

Churches

_01.jpg)

Madrid has a considerable number of Catholic churches, some of which are among the most important Spanish religious artworks.

The oldest church that survives today is San Nicolás de los Servitas, whose oldest item is the bell tower (12th century), in Mudéjar style. The next oldest temple is San Pedro el Real, with its high brick tower.

St. Jerome Church is a gothic church next to El Prado Museum. The Catholic Monarchs ordered its construction in the 15th century, as part of a vanished monastery. The monastery's cloister is preserved. It has recently been renovated by Rafael Moneo, with the goal to house the neoclassical collection of El Prado Museum, and also sculptures by Leone Leoni and Pompeo Leoni.

The Bishop Chapel is a gothic chapel built in the 16th century by order of the Bishop of Plasencia, Gutierre de Vargas. It was originally built to house the remains of Saint Isidore Laborer (Madrid's patron saint), but it was used as the Vargas family mausoleum. Inside are the altarpiece and the tombs of the Vargas family, which were the work of Francisco Giralte, a disciple of Alonso Berruguete. They are considered masterpieces of Spanish Renaissance sculpture.

_02.jpg)

St. Isidore Church was built between 1620 and 1664 by order of Empress Maria of Austria, daughter of Charles V of Germany and I of Spain, to become part of a school run by the Jesuits, which still exists today. Its dome is the first example of a dome drawing on a wooden frame covered with plaster, which, given its lightness, makes it easy to support the walls. It was the cathedral of Madrid between 1885 and 1993, which is the time it took to build the Almudena. The artworks inside were mostly burned during the Spanish Civil War, but it retained the tomb that holds the incorrupt body of Saint Isidore Laborer and the urn containing the ashes of his wife, Maria Torribia.

The Royal Convent of La Encarnación is an Augustinian Recollect convent. The institution, which belonged to ladies of the nobility, was founded by Queen Margaret of Austria, wife of Philip III of Spain, in the early 17th century. Due to the frescoes and sculptures it houses, it is one of the most prominent temples in the city. The building's architect was Fray Alberto de la Madre de Dios, who built it between 1611 and 1616. The façade responds to an inspiring Herrerian style, with great austerity, and it was imitated by other Spanish churches. The church's interior is a sumptuous work by the great Baroque architect Ventura Rodriguez.

In the church are preserved shrines containing the blood of St. Januarius and St. Pantaleon, the second (according to tradition) liquefies every year on the saint's day on 27 July.

San Antonio de los Alemanes (St. Anthony Church) is a pretty 17th-century church that was originally part of a Portuguese hospital. Subsequently, it was donated to the Germans living in the city.

The interior of the church has been recently restored. It has some beautiful frescoes painted by Luca Giordano, Francisco Carreño, and Francisco Rizi. The frescoes represent some kings of Spain, Hungary, France, Germany, and Bohemia. They all sit looking at the paintings in the vault, which represent the life of Saint Anthony of Padua.

The Royal Chapel of St. Anthony of La Florida is sometimes named the "Goya's Sistine Chapel". The chapel was built on orders of King Charles IV of Spain, who also commissioned the frescoes by Goya. These were completed over a six-month period in 1798. The frescoes portray miracles by Saint Anthony of Padua, including one that occurred in Lisbon but that the painter has relocated to Madrid. Every year on 13 June, the chapel becomes the site of a lively pilgrimage in which young unwed women come to pray to St. Anthony and ask for a partner.

San Francisco el Grande Basilica was built in neoclassical style in the second half of the 18th century by Francesco Sabatini. It has the fifth largest diameter dome to Christianity. (33 metres (108 feet) in diameter: it's smaller than the dome of Rome's Pantheon (43.4 metres or 142.4 feet), St. Peter's Basilica (42.4 metres or 139.1 feet), the Florence Cathedral (42 metres or 138 feet), and the Rotunda of Mosta (37.2 metres or 122.0 feet) in Malta, but it's larger than St. Paul's Cathedral (30.8 metres or 101 feet) in London and Hagia Sophia (31.8 metres or 104 feet) in Istanbul).

The church is dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi, who according to legend was established in Madrid during his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Its sumptuous interior features many artworks, including paintings by Goya and Zurbarán.

The Cathedral of Santa María la Real de la Almudena is the episcopal seat of the Archdiocese of Madrid. It is a temple 102 metres (335 feet) long and 73 metres (240 feet) high, built during the 19th and 20th centuries in a mixture of different styles: neoclassical exterior, neo-Gothic interior, neo-Romanesque crypt, and neo-Byzantine apse's paints.

The cathedral was built in the same place as the Moorish citadel (Al-Mudayna). It was consecrated by Pope John Paul II on his fourth trip to Spain on 15 June 1993, thus becoming the only Spanish cathedral dedicated by a pope.

Literature

_05.jpg)

Madrid has been one of the great centres of Spanish literature. Some of the best writers of the Spanish Golden Century were born in Madrid, including: Lope de Vega (Fuenteovejuna, The Dog in the Manger, The Knight of Olmedo), who reformed the Spanish theatre, a work continued by Calderon de la Barca (Life is a Dream), Francisco de Quevedo, Spanish nobleman and writer famous for his satires, which criticised the Spanish society of his time, and author of El Buscón. And finally, Tirso de Molina, who created the famous character Don Juan. Cervantes and Góngora also lived in the city, although they were not born there. The homes of Lope de Vega, Quevedo, Gongora and Cervantes are still preserved, and they are all in the Barrio de las Letras (District of Letters).

Other writers born in Madrid in later centuries have been Leandro Fernandez de Moratín, Mariano José de Larra, Jose de Echegaray (Nobel Prize in Literature), Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Dámaso Alonso, Enrique Jardiel Poncela and Pedro Salinas.

The "Barrio de las Letras" (District of Letters) owes its name to the intense literary activity developed over the 16th and 17th centuries. Some of the most prominent writers of the Spanish Golden Age settled here, as Lope de Vega, Quevedo or Góngora, and the theatres of Cruz and Príncipe, two of the major comedy theatres of that time. At 87 Calle de Atocha, one of the roads that limit the neighbourhood, was the printing house of Juan Cuesta, where the first edition of the first part of Don Quixote (1604) was published, one of the greatest works of Spanish literature. Most of the literary routes are articulated along the Barrio de las Letras, where you can find scenes from novels of the Siglo de Oro and more recent works like "Bohemian Lights".

Madrid is home to the Royal Academy of Spanish Language, an internationally important cultural institution dedicated to language planning by enacting legislation aimed at promoting linguistic unity within the Hispanic states; this ensures a common linguistic standard, in accordance with its founding statutes "to ensure that the changes undergone [by the language] [...] not break the essential unity that keeps all the Hispanic".[99]

Madrid is also home to another international cultural institution, the Instituto Cervantes, whose task is the promotion and teaching of the Spanish language as well as the dissemination of the culture of Spain and Hispanic America.

The National Library of Spain is the largest major public library in Spain. The library's collection consists of more than 26,000,000 items, including 15,000,000 books and other printed materials, 30,000 manuscripts, 143,000 newspapers and serials, 4,500,000 graphic materials, 510,000 music scores, 500,000 maps, 600,000 sound recording, 90,000 audiovisuals, 90,000 electronic documents, more than 500,000 microforms, etc.[100]

Commemorative plaque of the 1st edition of Don Quixote

Commemorative plaque of the 1st edition of Don Quixote Plaza de Santa Ana, Barrio de las Letras

Plaza de Santa Ana, Barrio de las Letras_2005_July.jpg)

Nightlife

The nightlife in Madrid is one of the city's main attractions. Tapas bars, cocktail bars, clubs, jazz lounges, live music venues, flamenco theatres, and establishments of all kinds cater to all. Every night, venues pertaining to the Live Music Venues Association La Noche en Vivo host a wide range of live music shows. Everything from acclaimed to up-and-coming artists, singer-songwriters to rock bands, jazz concerts or electronic music sessions to showcase music at its best.

Nightlife and young cultural awakening flourished after the death of Franco, especially during the 80s while Madrid's mayor Enrique Tierno Galván (PSOE) was in office. At this time, the cultural movement called La Movida flourished, and it initially gathered around Plaza del Dos de Mayo. Nowadays, the Malasaña area is known for its alternative scene.

Some of the most popular night destinations include the neighbourhoods of Bilbao, Tribunal, Atocha, Alonso Martínez or Moncloa, together with the Puerta del Sol area (including Ópera and Gran Vía, both adjacent to the popular square) and Huertas (Barrio de las Letras), destinations which are also filled with tourists day and night. The district of Chueca has also become a hot spot in the Madrilenian nightlife, especially for the gay population. Chueca is popularly known as the gay quarter, comparable to The Castro district in San Francisco.

What is also popular is the practice of meeting in parks or streets with friends and drinking alcohol together (this is called botellón, from botella, 'bottle'), but in recent years, drinking in the street is punished with a fine of €600.

Usually in Madrid people do not go out until later in the evening and do not return home until early in the morning. A typical evening out could start after 12:00 AM and end at 6:30 AM.

Bohemian culture

The city has venues for performing alternative art and expressive art. They are mostly located in the centre of the city, including in Ópera, Antón Martín, Chueca and Malasaña. There are also several festivals in Madrid, including the Festival of Alternative Art, the Festival of the Alternative Scene.[101][102][103][104]