Mabel Dwight

| Mabel Dwight | |

|---|---|

Mabel Dwight, self-portrait, 1932 | |

| Born |

Mabel Jacque Williamson January 31, 1875 |

| Died | September 4, 1955 (aged 80) |

| Known for | American artist, lithographer, watercolorist |

Mabel Dwight was an American artist whose lithographs showed scenes of ordinary life with humor and compassion.[1] Between the mid-1920s and the early 1940s she achieved both popularity and critical success. In 1936 Prints magazine named her one of the best living printmakers and a critic said she was one of the foremost lithographers in the United States.[2][3]

Early life and education

Born in Cincinnati and raised in New Orleans, she moved to San Francisco in the late 1880s. There, she studied with Arthur Mathews at the Mark Hopkins Institute.[4][5] She joined and became a director of the Sketch Club, the city's artists' association for women[6] and the club's tenth semi-annual exhibition in 1897 gave her the first opportunity to show her work to the public.[7][8] In her mid-20s she traveled extensively, visiting Egypt, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), India, and Java (now Indonesia).[6] Returning to the United States in 1903, she settled in Greenwich Village, then known as a locale friendly to artists.[4][5] For the next few years she tried to establish herself as a professional artist and was listed in the American Art Annual from 1903 to 1906 as a painter and illustrator.[9] She met and in 1906 married fellow artist Eugene Patrick Higgins. Although they were both socialists, and hence espoused equality of the sexes, Dwight fell into the role of help mate and stopped painting.[2][5][10]

In 1917 Dwight and Higgins separated and she resumed her painting career. The following year she joined Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney's newly founded Whitney Studio Club[11] and became secretary to Juliana Force, the club's director.[2] Over the next few years she attended life drawing sessions and showed at annual exhibitions that the club held. Although she made some experiments with etching, she worked mainly in watercolor at this time.[2][4][12]

Mature style

Dwight reached the age of 50 in 1925. Having been exposed to lithography when studying in San Francisco,[6][13] she met the New York art print dealer Carl Zigrosser some time before the outbreak of World War I, and, with his encouragement, traveled to Paris in 1926 to spend two years studying lithographic art in the Atelier Duchatel.[14] While in Paris, she made surreptitious sketches showing people engaged in everyday activities—watching puppet shows, sitting in cafés, worshiping at church, browsing stalls by the Seine—and worked up the sketches into lithographic prints. In their posture and gestures as much as their facial expressions, the characters she depicted show their personalities and individual foibles. This aspect of Dwight's mature style is clearly seen in Boulevard des Italiens of 1927 where the temperament of each person is made distinct.

From her earliest efforts onward, her pictures were artful celebrations of ordinariness. In them, Dwight's empathy for her subjects is apparent as well as her droll sense of humor. When she gave her Monkey House print the title The Brothers she was not making fun of the apes or the workmen spectators, but rather the priest who, shown turning his back on the scene, makes the picture into a gentle Darwinian joke. While most of her prints were black and white, a few, including Guignolette (1927), were enhanced by muted colors. As she pulled them off the lithographic stone, she would send proofs to Zigrosser for his critical review and after she returned to New York in 1927 he put her in touch with printmaker George Miller, whose expertise was the equal of the master printers at the Atelier Duchatel.[2]

Within a year of her return, the Paris prints and the ones she began to make in New York established her as one of America's best lithographic artists.[4][6][15] In 1928, Zigrosser gave her a first solo exhibit at the Weyhe Gallery.[2] Reviewing this show, a critic acknowledged Dwight's growing reputation, noted that her prints showed aspects of the humor of city life, and praised her for a style that was "quite without manner or a self-imposed technique."[16] She would later say that she chose print making so as to make her art available to a broad audience at reasonable cost.[4]

In 1929 the Print Club of Philadelphia gave her a retrospective solo exhibition including all the prints she had made in Paris, Chartres, and New York through the end of the previous year. In a lengthy review, Margaret Breuning of the New York Evening Post wrote that the show contained "gay happy lithographs accomplished by a true artist, whose affectionate pulse is nicely attuned to the heart beats of those she so faithfully depicts."[17]

Dwight liked to portray New Yorkers in public places and frequently worked in theaters. She would conceal her pencil and paper behind a large handbag in order to sketch performers and members of the audience. In 1928 she worked in Minsky’s National Winter Garden, a burlesque theater in the Lower East Side to make a series of lithographs and also illustrated an article, “The Last Days of Burlesque”, for the August 1929, issue of Vanity Fair.[18]

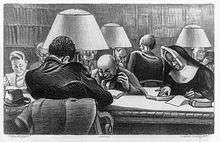

She made drawings of circus performances for an article in the April 1930 issue of Fortune magazine[5] and two years later was given a second solo exhibition at the Weyhe Gallery. In the latter she showed watercolors and drawings as well as lithographic prints. Her subjects were dark ones—old, decrepit houses on Staten Island, a stalking black cat, and graveyards in New Mexico and Paris—as well as the more festive scenes of parties and circus acts for which she had become known.[19] Her lithograph Night Work (1931) is literally dark, but the composition is pleasing rather than jarring and the tone is rather serene than despairing.

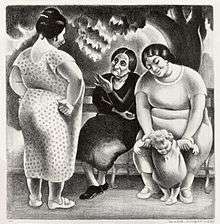

She maintained radical political views throughout her adult life. During the 1930s, she joined one of the Marxist John Reed Clubs and supported another Popular Front organization, the American Artists' Congress. Nonetheless, not wishing to become a propagandist and fearing she would lose sales that she needed to support her precarious existence, she rarely produced works of an overtly political character.[5][20] Dwight's Group in Central Park (1934) suggests the hardships endured by many citizens in the heart of the Depression, but its tone is gentle and the feeling conveyed to the viewer is an optimistic one. An untitled watercolor of 1936 showing an African American man and two women conversing while seated on a park bench is charming and lyrical; nothing about it suggests Depression conditions or the injustices racial discrimination.

In 1936 she was listed as one of America's best printmakers in Prints magazine[2] and that year produced what would become her most popular print, Queer Fish, which was one of a group of pictures made at the New York Aquarium in Battery Park.[4] That same year a newspaper critic called her "a foremost American lithographer" who had "climbed to the top of a difficult and highly competitive field."[3] When, during the second half of the 1930s, Dwight made lithographs for federal arts projects,[21] she retained her wry sense of humor and continued to show New Yorkers at their leisure. Mulberry Street Marionettes (1936), produced for the Federal Art Project, could just as well have been made in the prosperous years a decade earlier. While continuing to show her light touch in these years, her subjects also included wind-swept landscapes, laborers hard at work, and lonely and disconsolate individuals.

Although not much is known about her personal life, Dwight seems increasingly to have suffered from poverty, deafness, and poor health.[4][5] She retained nonetheless her sense of proportion and ability to empathize with others. In 1936 she wrote that "satire may play lightly with man's foibles—in kindly, ironic vein portray him not as such a bad fellow after all, but at times a rather absurd one." The artist, she said, may view "people with sympathy and translate them into art just as tragic and humorous as he may wish."[6] This kindly attitude shows plainly in works of the time, including Silence (1939), which, like her café scene of 1927 (Boulevard des Italiens), uses posture, gesture, and expression to show individual characteristics of each person who is depicted.

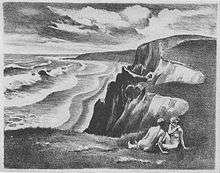

In 1938 Weyhe Gallery gave her a retrospective solo exhibition of 93 works that proved to be very successful.[22] Called "A Decade of Lithography", it covered the years from 1927 through 1937.[15][23] Citing her "rich, healthy human commentary", a reviewer said the show revealed the "love of life in its sprawling actuality" that was the main force of her art.[24] Included in the show were cityscapes like Ninth Avenue Church (1936) and a dramatic landscape with an improbable couple (Cliffs by the Sea, 1937), which give an idea of the range Dwight's artistic skill.

Dwight liked to include cats in her work and Backyard (1938) puts one as the main focus of the composition. She was also an excellent portraitist as her self-portrait (1932) and Boy Resting (1939) make plain.

Later life and work

The last years of the 1930s proved to be the high point of Dwight's career. In the early 1940s her work continued to appear in New York group shows, including the Weyhe Gallery (1941, 1942), a collaborative dealers' show at the American Fine Arts Building (1941), and National Academy of Design (1942), but after 1942 there were practically none.[25] Although she was less productive, her Summer Evening of 1945 is a rare late work showing that she retained her ability to make excellent art at the age of 70. During the decade after 1945, however, Dwight's health and her financial condition continued to deteriorate. During her final years she was confined to a nursing home and, in 1955, suffered a stroke and died.[4][5]

Family and personal life

Although she gave various dates of birth during the course of her adult life, Dwight was probably born on January 31, 1875 and named Mabel Jacque Williamson.[26] She was the only child of Paul Huston Williamson (born ca. 1837) and his wife Adelaide, or Ada (born ca. 1845) Jacque .[27]

Paul Williamson owned a farm near Cincinnati in Colerain Township, Hamilton County, Ohio. While Dwight was still a child,[27] the family moved to New Orleans[6] and Dwight was put in a convent school in Carrollton, outside the city.[5] A few years later the Williamsons moved to San Francisco where Dwight was privately tutored while attending high school.[5][6] In the mid-1890s Dwight completed her secondary education and began studies under Arthur Mathews at the Mark Hopkins Institute.[4][5][6] At the turn of the century she embarked on extensive travels to the Middle- and Far East.[6] On returning in 1903 she settled with her parents in Greenwich Village, which was at that time a congenial neighborhood for young people who had both ambitions in the arts and progressive ideals.[5][6] While at the Mark Hopkins Institute she had become attached to the cause of socialism and she would retain radical social beliefs for the rest of her life. Later in life she said that discovering radical politics was like "getting religion" and, judging from the subjects of some of her prints, it appears she was not an atheist, but retained an attachment to Christianity in general and Roman Catholicism in particular.[6]

Not long after settling in Greenwich Village she met Eugene Patrick Higgins, a young artist who shared her political beliefs. On October 3, 1906, the two were married in a religious ceremony.[28] Although they had no children, Dwight became housewife and helpmate. Upon her marrying, she later wrote, "domesticity followed and for many years (my) career as an artist was in abeyance."[5] The two separated in 1917 and divorced in 1921.[4] While they were separated, Dwight's friend Carl Zigrosser introduced her to Roderick Seidenberg, an architectural draftsman. He was, like Higgins, a militant socialist, but where Higgins was a year older than Dwight, Seidenberg was 14 years younger. Their relationship grew close and for some years they lived together. They became estranged after Seidenberg fell in love with, and then married another woman. Dwight and Seidenberg would become reconciled when Dwight suffered periods of illness during the 1930s and 1940s and Seidenberg and his wife Catherine took her into their home in order to care for her.[6][29][30]

Following her divorce from Higgins she neither kept her married nor resumed her maiden name, but rather, for reasons she did not disclose, chose the surname Dwight.[4][6] Her reticence about her name was not unusual in her. Even though she wrote an (unpublished) autobiography, much about her life is unknown. Her ability to hear is an example. Most biographic summaries do not mention a hearing disability. Some say she was deaf, but do not specify the degree of hearing loss.[31] One source says she was partly deaf[32] and another says she was profoundly so.[33]

In 1929 or 1930 she traveled to New Mexico and this appears to have been the first and only time she traveled outside the Mid-Atlantic states after her return from Paris.[34] At about this time she moved from Greenwich Village to Staten Island and some time later moved to Pipersville, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.[35] After Dwight turned 65 in 1940, her deafness, chronic asthma, and poverty worsened. Although she continued to work, her output dwindled, and she was confined to nursing homes in the period before her death following a stroke in 1955.[1]

Collections

Dwight's prints are held by major museums in the United States and Europe including the following:

- Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

- Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

- Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

- Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

- Buffalo Museum, Buffalo, New York

- Canton Museum of Art, Canton, Ohio

- Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

- Cleveland Museum, Cleveland, Ohio

- Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas

- Detroit Museum, Detroit, Michigan

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco-Legion of Honor, San Francisco, California

- Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University Of Oklahoma, Norman

- Frederick R Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

- Georgia Museum of Art, University Of Georgia, Athens

- Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, South Carolina

- Godwin-Ternbach Museum, Queens College, Flushing, New York

- Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire

- Kupferstich Kabinett, Berlin

- Maier Museum of Art, Randolph-Macon Woman's College, Lynchburg, Virginia

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia

- Museum of Fine Art, Boston, Massachusetts

- National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC

- National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

- New York Public Library, New York

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Print Club of Albany, Fort Orange Station, Albany, New York

- Saint Joseph College Art Gallery, West Hartford, Connecticut

- San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, California

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

- Slater Memorial Museum, Norwich, Connecticut

- Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

- Southern Alleghenies Museum of Art, Loretto, Pennsylvania

- Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, Illinois

- University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa

- University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor

- University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

- University of Wyoming Art Museum, Laramie

- Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Exhibitions

Dwight exhibited mainly at the Weyhe Gallery in New York. Other exhibitions included the following:

- American Artist’s Congress, 1936

- American Institute of Graphic Arts, 'Fifty Prints of the Year', 1930 (traveling exhibition)

- Art Institute of Chicago, 1930, 1933, 1935

- Downtown Gallery, 1928, 1931, 1935

- Mexico City, 1929

- National Academy of Design, 1934

- Print Club of Philadelphia, 1929, 1932, 1935

- Society of American Etchers, 1937

Further reading

Dwight, Mabel, "Satire in Art," in Art for the Millions; Essays From the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, edited by Francis V. O'Connor, pp. 151–154. Boston, New York Graphic Society, 1975

Henkes, Robert. American Women Painting of the 1930s and 1940s; The Lives and Work of Ten Artists. Jefferson, N.C.; McFarland, 1991

Robinson, Susan Barnes, and John Pirog. Mabel Dwight: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997

Zigrosser, Carl. "Mabel Dwight: Master of Comédie Humaine." Artnews, Vol. 6, No. 126 (June 1949) pp. 42–45

References

- 1 2 "Mabel Dwight. American, 1875 - 1955". ArtLine. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 David W. Kiehl (1997). Between the wars : women artists of the Whitney Studio Club and Museum. Whitney Museum of American Art. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4381-0791-2.

- 1 2 "Just Between Ourselves". Times Record, Troy, New York. 1936.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Paul Anbinder, ed. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. Hudson Hills. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-55595-198-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Mabel Dwight: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs by Susan Barnes Robinson and John Pirog Frankenthaler: A Catalogue Raisonné, Prints 1961-1994 by Pegram Harrison and Suzanne Boorsch" (PDF). Woman's Art Journal. 20 (2): 52–55. Autumn 1999. JSTOR 1358988. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Carol Kort; Liz Sonneborn (1 January 2002). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. Infobase Publishing. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-4381-0791-2.

- ↑ "Art and the Artists". San Francisco Call. 1897-11-07. p. E7.

Chinatown must have been turned loose while the artists of the Sketch Club were preparing for this year's display.... and Mabel Williamson have all then up this subject.

- ↑ "Mabel Dwight, January 31, 1875-September 04, 1955". Clara Database of Women Artists, National Museum of Women in the Arts. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ↑ American Art Annual, Volume 5, 1905-06. American Art Annual, New York. 1905. p. 491.

WILLIAMSON. MABEL. 60 Washington Square S., New York, N. Y. (P., I.)

- ↑ She later wrote: "domesticity followed and for many years (my) career as an artist was in abeyance." (Robinson, Susan Barnes, and John Pirog. Mabel Dwight: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997)

- ↑ The Whitney Studio Club was an organization for promoting modern American art that evolved into the present-day Whitney Museum of American Art

- ↑ "Whitney Studio Club". New York Times (display ad). 1923-12-23. p. 9.

Exhibition and sale of paintings, etchings, and monotypes by Henry R. Beekman, Mildred M. Coughlin, Mabel Dwight, John A. Ten Eyck III; Dec. 19th to Jan. 2nd.

- ↑ Her instructor, Arthur Mathews, had learned lithography while working as a designer and illustrator in a litho shop. (A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts, Infobase Publishing, 2002, pp. 56–57)

- ↑ The Atelier Duchatel was a studio run by the widow of French lithographic printer Édouard Duchatel. (Paul Anbinder, ed., An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum, Hudson Hills, 2001, p. 230)

- 1 2 "Mabel Dwight, 79, An Artist, Is Dead". New York Times. 1955-09-05. p. 11.

- ↑ "American Print Makers; Second Exhibition at Downtown Gallery is Hailed as the Season's Livest Symposium". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1928-12-16.

Just at present burlesque shows and the circus are affording suggestive subject matter to a number of the exhibitors, notably Reginald Marsh, Ernest Fiene, and Mabel Dwight. These artists are all experimenting with lithography, which again might be described as a characteristic of the group—almost its common denominator.

- ↑ C. H. Bonte (1939-01-20). "In Gallery and Studio; An Intensely Modernistic Exhibition and Two Others That Are Just Slightly Tinged; Nine-Woman Show at the Plastic Club and Mabel Dwight's Richly Humorous Lithographs". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ↑ "Mabel Dwight". Keith Sheridan Fine Prints. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1932-01-09). "Mabel Dwight in Varied Moods". New York Times. p. 20.

- ↑ The anti-fascist, Danse Macabre (1933) and anti-capitalist Merchants of Death (1935) are her two best-known political works. (Robinson, Susan Barnes, and John Pirog. Mabel Dwight: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997)

- ↑ Between 1935 and 1939, she worked first for the Public Works of Art Project and then for the Federal Art Project of the Works Projects Administration.

- ↑ Howard Devree (1938-01-30). "A Reviewer's Notebook: Comment on Some of the Newly Opened Exhibitions Current in Galleries". New York Times. p. 160.

- ↑ "Among the Solo Shows". New York Times. 1938-01-09. p. X10.

- ↑ ""The Eight" and Other U.S. Artists Exhibit". New York Post. 1938-01-22. p. 19.

- ↑ This list of shows comes from articles appearing in the New York Times, 1940 to 1946, passim. Dwight was reported to appear in only one group show after 1942: at Grand Central Galleries in 1946.

- ↑ For example, she gave her birth date as January 29, 1877, on returning to New York in 1909 ("New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1957", index and images, FamilySearch, accessed 21 Aug 2014). Most sources say she was born January 31, 1875.

- 1 2 "Paul H Williamson, Colerain, Hamilton, Ohio, United States". United States Census, 1880, sheet 68C, NARA microfilm publication T9 on FamilySearch.org. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- ↑ "Eugene Patrick Higgins and Mabel Jacque Williamson, 03 Oct 1906". New York Marriages, 1686-1980; FHL microfilm 1558673 on FamilySearch.org. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- ↑ "Guide to the Roderick Seidenberg and Mabel Dwight Collection". Digital Collections, Langsdale Library, University of Baltimore. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- ↑ "Mabel Dwight Correspondence with Carl Zigrosser, 1915-1967, n.d.". Franklin Library, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ "Mabel Dwight". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ↑ "Oral history interview with Holger Cahill, 1960 Apr. 12 and Apr. 15". Oral Histories; Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Christine Bold (1999). The WPA Guides: Mapping America. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-57806-195-2.

Mabel Dwight's lithograph "Derelicts (East River Water Front" represents the same subject matter in more grotesque yet more intimate light: her men touch and lean on each other with a degree of dependency not indicated by the more public photograph. Dwight—an elderly, partly deaf employee of the New York City Art Project—generally makes graphic the quotidian camaraderie of the working classes and the destitute, humanizing some of the guidebook's stark information.

- ↑ "Mabel Dwight". AskArt Artists' Bluebook. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- ↑ "Mabel Dwight, Artist, Dies". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1955-09-06. p. 32.