Maarrat al-Nu'man

| Ma‘arrat al-Nu‘man معرة النعمان Maarat al-Numaan | |

|---|---|

|

A collage of Maarat al-Numan showing city's important landmarks. | |

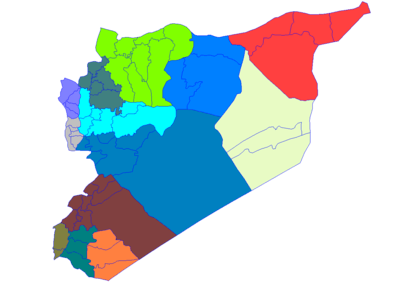

Ma‘arrat al-Nu‘man Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 35°38′N 36°40′E / 35.633°N 36.667°E | |

| Country |

|

| Governorate | Idlib |

| District | Maarrat al-Nu‘man |

| Subdistrict | Maarrat al-Nu‘man |

| Occupation | Jaish al-Fatah |

| Elevation | 522 m (1,713 ft) |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 58,008 |

Maarat al-Numaan (Arabic: مَعَرَّة النُّعْمَان, Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān), also known as al-Maʿarra, is a city in northwestern Syria, 33 km (21 mi) south of Idlib and 57 km (35 mi) north of Hama, with a population of about 58,008 (2004 census). It is located at the highway between Aleppo and Hama and near the Dead Cities of Bara and Serjilla. The city, known as Arra to the Greeks, has its present-day name combined of the Greek name and of its first Muslim governor an-Nu‘man ibn Bashir, a companion of Muhammad. The Crusaders called it Marre.

Today the city has a museum with mosaics from the Dead Cities, the Great Mosque of Maarrat al-Numan, a madrassa built by Abu al-Farawis from 1199 and remains of the medieval citadel. The city is also a birthplace of the poet Al-Maʿarri (973–1057).

History

In 891 Ya‘qubi described Maarrat al-Nu‘man as "an ancient city, now a ruin. It lies in the Hims province."[1] By the time of Estakhri (951) the place had recovered, as he described the city "very full of good things, and very opulent". Figs, pistachios and vines were cultivated.[1] In 1047 Nasir Khusraw visited the city, and described it as a populous town with a stone wall. There was a Friday Mosque, on a height, in the middle of the town. The bazaars were full of traffic. Considerable areas of cultivated land surrounded the town, with plenty of fig-trees, olives, pistachios, almonds and grapes.[1][2]

Massacre of Ma‘arra

The most infamous event from the city's history dates from late 1098, during the First Crusade. After the Crusaders, led by Raymond de Saint Gilles and Bohemond of Taranto, successfully besieged Antioch they found themselves with insufficient supplies of food. Their raids on the surrounding countryside during the winter months did not help the situation. By December 12 when they reached Ma‘arra, many of them were suffering from starvation and malnutrition. They managed to breach the city's walls and massacred about 8000 inhabitants. However, this time, as they could not find enough food, they resorted to cannibalism.[3]

One of the crusader commanders wrote to Pope Urban II: "A terrible famine racked the army in Ma‘arra, and placed it in the cruel necessity of feeding itself upon the bodies of the Saracens.[3]

Radulph of Caen, another chronicler, wrote: "In Ma‘arra our troops boiled pagan adults in cooking-pots; they impaled children on spits and devoured them grilled."[3]

These events were also chronicled by Fulcher of Chartres, who wrote: "I shudder to tell that many of our people, harassed by the madness of excessive hunger, cut pieces from the buttocks of the Saracens already dead there, which they cooked, but when it was not yet roasted enough by the fire, they devoured it with savage mouth."[4]

Among the European records of the incident was the French poem 'The Leaguer of Antioch', which contains such lines as,

- Then came to him the King Tafur, and with him fifty score

- Of men-at-arms, not one of them but hunger gnawed him sore.

- Thou holy Hermit, counsel us, and help us at our need;

- Help, for God's grace, these starving men with wherewithal to feed.'

- But Peter answered, 'Out, ye drones, a helpless pack that cry,

- While all unburied round about the slaughtered Paynim lie.

- A dainty dish is Paynim flesh, with salt and roasting due.

- From "The Leaguer of Antioch"[5]

Those events had a strong impact on the local inhabitants of Southwest Asia. The crusaders already had a reputation for cruelty and barbarism towards Muslims, Jews and even local Christians, Catholic and Orthodox alike (the Crusades began shortly after the Great Schism of 1054).

The accuracy of the events described by the contemporary writers have been disputed. The famine and cannibalism are recognised but the torture and killing of Muslim captives for cannibalism by Radulph of Caen are very unlikely since there are no Arab or Muslim records of the events. Had they occurred they would have undoubtedly been recorded. This has been noted by BBC Timewatch series, the episode The Crusades: A Timewatch Guide , which included the experts Dr Thomas Asbridge and Muslim Arabic historian Dr Fozia Bora, who states Radulph of Caen's description does not appear in Muslim contemporary chronicles.,[6][7][8]

Late medieval period

Ibn al-Muqaddam received lands in Maarat al-Nuʿman in 1179 as part of his compensation for yielding Baalbek to Saladin's brother Turan Shah. Ibn Jubayr passed by the town in 1185, and wrote that "Everywhere around the town are gardens... It is one of the most fertile and richest lands in the world".[2] Ibn Battuta visited in 1355, and described the town as small. The figs and pistachios of the town were exported to Damascus.[9]

Syrian Civil War

The town was the focus of intense protests against the government of President Bashar al-Assad on 2 June 2011.

On 25 October 2011, clashes occurred between loyalists and defected soldiers at a roadblock on the edge of the town. The defectors launched an assault on the government held roadblock in retaliation for a raid on their positions the previous night.[10] FSA takes control in December 2011–January 2012. The regime recaptures it at a later date. On 10 June 2012, the FSA takes it back, but the military recapture it in August.[11]

As the Syrian Civil War followed, the town's strategic position on the road between Damascus and Aleppo made it a significant prize. Starting October 8, 2012, the Battle of Maarrat al-Nu'man was fought between the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian Army, causing numerous civilian casualties and severe material damage.

A hospital in Maarrat al-Nu'man was struck by at least 4 missiles on February, 15th, 2016.[12][13][14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 le Strange, 1890, p. 495

- 1 2 le Strange, 1890, p. 496

- 1 2 3 Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, trans. Jon Rothschild (News York: Schocken Books, 1984), 39.

- ↑ Edward Peters, The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), 84.

- ↑ Von Sybel; History and Literature of the Crusades; translated by Lady Duff Gordon

- ↑ "A Timewatch Guide". RadioTimes. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "The Crusades: A Timewatch Guide". TVGuide.co.uk. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "The First Crusade: A New History: Amazon.co.uk: Thomas Asbridge: 9780743220842: Books". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ le Strange, 1890, p. 497

- ↑ "Assad forces fight deserters at northwestern town". Reuters. 25 October 2011.

- ↑ "Syria sends extra troops after rebels seize Idlib: NGO". English.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg, Germany (15 February 2016). "Syrien: Ärzte-ohne-Grenzen-Krankenhaus bombardiert - ein gezielter Angriff?". SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "Un hôpital de MSF en Syrie touché par des frappes aériennes". Radio-Canada.ca. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "MSF-backed hospital in Syria destroyed by air strikes: statement". Reuters. 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

- Sources

- Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. Schocken, 1989, ISBN 0-8052-0898-4

- le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ma'arrat al-Numan. |

External links

- Encyclopedia of the Orient: Crusades

- Utah Indymedia: The Cannibals of Ma`arra

- Telegraph.co.uk: "Syria-bloody-protests-over-the-slaying-of-30-children"

Coordinates: 35°38′19″N 36°40′18″E / 35.63861°N 36.67167°E