Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

| |

|

The MBTA provides services in five different modes (boat not pictured) around Greater Boston. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Greater Boston |

| Transit type | |

| Number of lines |

|

| Number of stations | |

| Daily ridership | 1,277,200 (weekday, Q4 2015)[6] |

| Chief executive | Brian Shortsleeve (interim)[7] |

| Headquarters |

|

| Website |

mbta |

| Operation | |

| Began operation |

|

| Operator(s) |

|

| Technical | |

| System length |

|

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (abbreviated the MBTA and The T)[9][10] is the public agency responsible for operating most public transportation services in Greater Boston, Massachusetts. Earlier modes of public transportation in Boston were independently owned and operated; many were first folded into a single agency with the formation of the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) in 1947. The MTA was replaced in 1964 with the present-day MBTA, which was established as an individual department within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts before becoming a division of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) in 2009.

The MBTA and Philadelphia's Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) are the only U.S. transit agencies that operate all five major types of terrestrial mass transit vehicles: light rail vehicles (the Ashmont–Mattapan High Speed and Green Lines); heavy rail trains (the Blue, Orange, and Red Lines); regional rail trains (the Commuter Rail); electric trolleybuses (the Silver Line); and motor buses (MBTA Bus).[11] In 2008, the system averaged 1.3 million passenger trips each weekday, of which the subway averaged 598,200, making it the fourth-busiest subway system in the United States.[12][13] Further, the Green Line and Ashmont–Mattapan High Speed Line comprise the busiest light-rail system in the U.S., with a weekday ridership of 255,100.

The MBTA is the largest consumer of electricity in Massachusetts, and the second-largest land owner (after the Department of Conservation and Recreation).[14][15] In 2007, its CNG bus fleet was the largest consumer of alternative fuels in the state.[16] The MBTA operates an independent law enforcement agency, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Police.

History

Mass transportation in Boston was provided by private companies, often granted charters by the state legislature for limited monopolies, with powers of eminent domain to establish a right-of-way, until the creation of the MTA in 1947. Development of mass transportation both followed and shaped economic and population patterns.

Railways

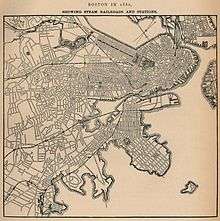

Shortly after the steam locomotive became practical for mass transportation, the private Boston and Lowell Railroad was chartered in 1830, connecting Boston to Lowell, a major northerly mill town in northeast Massachusetts' Merrimack Valley, via one of the oldest railroads in North America. This marked the beginning of the development of American intercity railroads, which in Massachusetts would later become the MBTA Commuter Rail system and the Green Line "D" Branch.

Streetcars

Starting with the opening of the Cambridge Railroad on March 26, 1856, a profusion of streetcar lines appeared in Boston under chartered companies.[17] Despite the change of companies, Boston is the city with the oldest continuously working streetcar system in the world. Many of these companies consolidated, and animal-drawn vehicles were converted to electric propulsion.[17]

Subways and elevated railways

Streetcar congestion in downtown Boston led to the subways in 1897 and elevated rail in 1901. The Tremont Street Subway was the first rapid transit tunnel in the United States. Grade-separation added capacity and avoided delays caused by cross streets.[18] The first elevated railway and the first rapid transit line in Boston were built three years before the first underground line of the New York City Subway, but 34 years after the first London Underground lines, and long after the first elevated railway in New York City, its Ninth Avenue El started operations on July 1, 1868 in Manhattan as an elevated cable car line.

Various extensions and branches were added at both ends, bypassing more surface tracks. As grade-separated lines were extended, street-running lines were cut back for faster downtown service. The last elevated heavy rail or "El" segments in Boston were at the extremities of the Orange Line: its northern end was relocated in 1975 from Everett to Malden, MA, and its southern end was relocated into the Southwest Corridor in 1987. However, the Green Line's Causeway Street Elevated remained in service until 2004, when it was relocated into a tunnel with an incline to reconnect to the Lechmere Viaduct. The Lechmere Viaduct and a short section of steel-framed elevated at its northern end remain in service, though the elevated section will be cut back slightly and connected to a northwards viaduct extension in 2017 as part of the Green Line Extension.

Public enterprise

The old elevated railways proved to be an eyesore and required several sharp curves in Boston's twisty streets. The Atlantic Avenue Elevated was closed in 1938 amidst declining ridership and was demolished in 1942. As rail passenger service became increasingly unprofitable, largely due to rising automobile ownership, government takeover prevented abandonment and dismantlement. The MTA purchased and took over subway, elevated, streetcar, and bus operations from the Boston Elevated Railway in 1947.[19]

In the 1950s, the MTA ran new subway extensions, while the last two streetcar lines running into the Pleasant Street Portal of the Tremont Street Subway were substituted with buses in 1953 and 1962.

While the operations of the MTA were relatively stable by the early 1960s, the privately operated commuter rail lines were in freefall. The New Haven Railroad, New York Central Railroad, and Boston and Maine Railroad were all financially struggling; deferred maintenance was hurting the mainlines while most branch lines had been discontinued. The 1945 Coolidge Commission plan assumed that most of the commuter rail lines would be replaced by shorter rapid transit extensions, or simply feed into them at reduced service levels. Passenger service on the entire Old Colony Railroad system serving the southeastern part of the state was abandoned by the New Haven Railroad in 1959, triggering calls for state intervention. Between January 1963 and March 1964, the Mass Transportation Commission tested different fare and service levels on the B&M and New Haven systems. Determining that commuter rail operations were important but could not be financially self-sustaining, the MTC recommended an expansion of the MTA to commuter rail territory.[20]

On August 3, 1964, the MBTA succeeded the MTA, with an enlarged service area intended to subsidize continued commuter rail operations. The original 14-municipality MTA district was expanded to 78 cities and towns.[21] Several lines were briefly cut back while contracts with out-of-district towns were reached, but, except for the outer portions of the Central Mass Branch (cut back from Hudson to South Sudbury), West Medway Branch (cut back from West Medway to Millis), Blackstone Line (cut back from Blackstone to Franklin), and B&M New Hampshire services (cut back from Portsmouth to Newburyport), these cuts were temporary; however, service on three branch lines (all of them with only one round trip daily: one morning rush-hour trip in to Boston, and one evening rush-hour trip back out to the suburbs) was dropped permanently between 1965 and 1976 (the Millis (the new name of the truncated West Medway Branch) and Dedham Branches were discontinued in 1967, while the Central Mass Branch was abandoned in 1971). The MBTA bought the Penn Central (New York Central and New Haven) commuter rail lines in January 1973, Penn Central equipment in April 1976, and all B&M commuter assets in December 1976; these purchases served to make the system state-owned with the private railroads retained solely as operators.[21] Only two branch lines were abandoned after 1976: service on the Lexington Branch (also with only one round trip daily) was discontinued in January 1977 after a snowstorm blocked the line, while the Lowell Line's full-service Woburn Branch was eliminated in January 1981 due to poor track conditions.

The MBTA assigned colors to its four rapid transit lines in 1965, and lettered the branches of the Green Line from north to south. Shortages of streetcars, among other factors, caused bustitution of rail service on two branches of the Green Line. The "A" Branch ceased operating entirely in 1969 and was replaced by the 57 bus,[21] while the "E" Branch was truncated from Arborway to Heath Street in 1985, with the section between Heath Street and Arborway being replaced by the 39 bus.[21]

The MBTA purchased bus routes in the outer suburbs to the north and south from the Eastern Massachusetts Street Railway in 1968.[21] As with the commuter rail system, many of the outlying routes were dropped shortly before or after the takeover due to low ridership and high operating costs.

In the 1970s, the MBTA received a boost from the Boston Transportation Planning Review area-wide re-evaluation of the role of mass transit relative to highways. Producing a moratorium on highway construction inside Route 128, numerous mass transit lines were planned for expansion by the Voorhees-Skidmore, Owings and Merrill-ESL consulting team. The removal of elevated lines continued, and the closure of the Washington Street Elevated in 1987 brought the end of rapid transit service to the Roxbury neighborhood. Between 1971 and 1985, the Red Line was extended both north and south, providing not only additional subway system coverage, but also major parking structures at several of the terminal and intermediate stations.[21]

Kickback schemes

Between 1980 and 1981, Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation and MBTA Chairman Barry Locke and the Assistant Director of the MBTA's Real Estate Department Frank J. Walters, Jr. ran a number of kickback schemes at the MBTA. The kickbacks were discovered when MBTA General Manager James O'Leary accidentally opened an envelope meant for Locke that contained the proceeds from one of the schemes. A total of seventeen people and one corporation would be indicted for their roles in kickback schemes at the MBTA.[22] Locke was convicted of five counts of bribery and sentenced to 7 to 10 years in prison. Locke is the only Massachusetts Cabinet Secretary to be convicted of a felony while in office since the state's adoption of the cabinet system in 1970.[23][24]

21st century

By 1999, the district was expanded further to 175 cities and towns, adding most that were served by or adjacent to commuter rail lines, though the MBTA did not assume responsibility for local service in those communities adjacent to or served by commuter rail.

A turning point in funding occurred in 2000. Prior to July 1, 2000, the MBTA was reimbursed by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for all costs above revenue collected (net cost of service). Beginning on that date, the T was granted a dedicated revenue stream consisting of amounts assessed on served cities and towns, along with a dedicated 20% portion of the 5% state sales tax. The MBTA now had to live within this "forward funding" budget.

The Commonwealth assigned to the MBTA responsibility for increasing public transit to compensate for increased automobile pollution from the Big Dig. The T submerged a nearby portion of the Green Line and rebuilt Haymarket and North Stations during Big Dig construction. However, these projects have strained the MBTA's limited resources, since the Big Dig project did not include funding for these improvements. Since 1988, the MBTA has been the fastest expanding transit system in the country, even as Greater Boston has been one of the slowest growing metropolitan areas in the United States.[25] When, in 2000, the MBTA's budget became limited, the agency began to run into debt from scheduled projects and obligatory Big Dig remediation work, which have now given the MBTA the highest debt of any transit authority in the country. In an effort to compensate, rates underwent an appreciable hike on January 1, 2007. Increasingly, local advocacy groups are calling on the state to assume $2.9 billion of the authority's now approximate debt of $9 billion, the interest on which severely limits funds available for required projects.[26]

In 2006, the creation of the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority saw Framingham, Natick, Weston, Sudbury, Wayland, Marlborough, Ashland, Sherborn, Hopkinton, Holliston, and Southborough subtract their MWRTA assessment from their MBTA assessment. Communities that are also members of other RTAs such as CATA, MVRTA, LRTA, WRTA, GATRA, and BAT may also subtract their RTA assessment from their MBTA assessment. The amount of funding the MBTA received remained the same; the assessment on remaining cities and towns increased but is still allocated by the same formula.

On October 31, 2007, the MBTA reestablished commuter rail service to the Greenbush section of Scituate, the third branch of the Old Colony service.[27] Rail renovation on the Green Line "D" Branch took place in the summer of 2007. New, low-floor cars on the line were introduced on December 1, 2008.

In 2008, Daniel Grabauskas, then the MBTA General Manager, revealed that the MBTA cut trips from published train and bus schedules without informing passengers, referred to as “hidden service cuts”, saying this misrepresentation of service had been happening for years. Grabauskas said this practice has been ended.[28]

On May 28, 2008, a westbound trolley on the Green Line "D" Branch slammed into a stopped train between the Waban and Woodland stations shortly after 6 p.m. At least seven people were injured, and the operator of the moving train, Terrese Edmonds, 24, was killed.[29] On May 8, 2009, two Green Line trolleys collided between Park Street and Government Center when the driver of one of them, 24-year-old Aiden Quinn, was text messaging his girlfriend.[30] A rule banning cell phones for operators while driving their bus, train, or streetcar was put into place days later.[31] On June 26, 2009, Governor Deval Patrick signed a law to place the MBTA along with other state transportation agencies within the administrative authority of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), with the MBTA now part of the Mass Transit division (MassTrans).[32][33][34][35] The 2009 transportation law continued the MBTA corporate structure and changed the MBTA board membership to the five Governor-appointed members of the Mass DOT Board.[36]

Rhode Island, which has funded commuter rail service to Providence since 1988, paid for extensions of the Providence/Stoughton Line to T.F. Green Airport in 2010 and Wickford Junction in 2012. The Fairmount Line, located entirely in the southern reaches of Boston, has been undergoing an improvement project since 2002. The first new station, Talbot Ave, opened in November 2012.[37]

Immediately following the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, the MBTA was partially shut down and National Guardsmen were deployed in various stations around the city.[38] During the ensuing manhunt for Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev the MBTA was fully shut down until the stay-inside request for Watertown, Cambridge, Belmont, and Boston was lifted.[39] During the manhunt, MBTA buses were used to ferry police around the city. After the suspect was caught the MBTA resumed normal service. The next day the MBTA began displaying "BOSTON STRONG" and "WE ARE ONE BOSTON" on buses and subway cars, in addition to the destination that is normally displayed.[40]

Services

Mode share of ridership on MBTA services in 2013[41]

Buses

The MBTA bus system is the nation's sixth largest by ridership and comprises over 150 routes across the Greater Boston area. The area served by the MBTA's bus operations is somewhat larger than that served by its subway and light rail, but is significantly smaller than that served by the MBTA's commuter rail operation. At least eight other regional transit authorities also provide bus services within that larger area, these being the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority, Brockton Area Transit Authority, Cape Ann Transportation Authority, Greater Attleboro Taunton Regional Transit Authority, Lowell Regional Transit Authority, Merrimack Valley Regional Transit Authority, Montachusett Regional Transit Authority, and Worcester Regional Transit Authority. All of these authorities have their own fare structures and some subcontract operation to private bus companies. In many cases, their buses serve as feeders to the MBTA commuter rail.[42]

Within MBTA's bus service area, transfers from the subway are free if using a CharlieCard (for local buses); transfers to the subway require paying the difference between bus and the higher subway fare (for local buses; if not using a CharlieCard, full subway fare must be paid in addition to full bus fare). Bus-to-bus transfers (for local buses) are free unless paying cash. Many of the outlying routes run express along major highways to downtown. The buses are colored yellow on maps and in station decor.

The Silver Line is the MBTA's first service designated as bus rapid transit (BRT), even though it lacks many of the characteristics of bus rapid transit.[43][44] The first segment began operations in 2002, replacing the 49 bus, which in turn replaced the Washington Street Elevated section of the Orange Line. A full subway fare was charged, with free transfers to the subways downtown until January 1, 2007, when the fare system was revised to categorize the service as a "bus" for fare purposes. The "Washington Street" segment runs along various downtown streets, and mostly in dedicated bus lanes on Washington Street itself.[45]

The "Waterfront" section opened at the end of 2004, and connects South Station to South Boston, partly via a tunnel and partly on the surface. These buses run dual-mode, trackless trolley in the tunnel and diesel bus outside. Service to Logan Airport began in June 2005. The Waterfront segment is classified as a "subway" for fare purposes.[45] A transfer between segments is possible at South Station.

A "Phase III" tunneled segment was proposed to connect the two segments for through service, but it was controversial due to high cost and the fact that many did not consider Phase I to be adequate replacement service for the old Elevated. All Phase III tunneling proposals have been suspended due to lack of funds, as has the Urban Ring, which was intended to expand upon existing crosstown buses. However, improvements in crosstown bus services, including a new route to Chelsea, are still being planned and implemented.

The MBTA contracts with private bus companies to provide subsidized service on certain routes outside of the usual fare structure. These are known collectively as the HI-RIDE Commuter Bus service, and are not numbered or mapped in the same way as integral bus services.[46]

Four routes connecting to Harvard Station (Red Line) still run as trackless trolleys; there was once a much larger trackless trolley system.[47] (See Trolleybuses in Greater Boston.)

In FY2005, there were on average 363,500 weekday boardings of MBTA-operated buses and trackless trolleys (not including the Silver Line), or 31.8% of the MBTA system. Another 4,400 boardings (0.38%) occurred on subsidized bus routes operated by private carriers.[48]

Subway

The subway system has three heavy rail rapid transit lines (the Red, Orange and Blue Lines), and two light rail lines (the Green Line and the Ashmont–Mattapan High Speed Line, the latter designated an extension of the Red Line). The system operates according to a spoke-hub distribution paradigm, with the lines running radially between central Boston and its environs.[9] It is common usage in Boston to refer to all four of the color-coded rail lines which run underground as "the subway" or "the T", regardless of the actual railcar equipment used.[9]

All four subway lines cross downtown, forming a quadrilateral configuration, and the Orange and Green Lines (which run approximately parallel in that district) also connect directly at two stations just north of downtown. The Red Line and Blue Line are the only pair of subway lines which do not have a direct transfer connection to each other. Because the various subway lines do not consistently run in any given compass direction, it is customary to refer to line directions as "inbound" or "outbound". Inbound trains travel towards the four downtown transfer stations, and outbound trains travel away from these hub stations.[9]

The Green Line has four branches in the west: "B" (Boston College), "C" (Cleveland Circle), "D" (Riverside), and "E" (Heath Street). The "A" Branch formerly went to Watertown, filling in the north-to-south letter assignment pattern, and the "E" Branch formerly continued beyond Heath Street to Arborway.

The Red Line has two branches in the south—Ashmont and Braintree, named after their terminal stations.

The colors were assigned on August 26, 1965 in conjunction with design standards developed by Cambridge Seven Associates,[49] and have served as the primary identifier for the lines since the 1964 reorganization of the MTA into the MBTA. The Orange Line is so named because it used to run along Orange Street (now lower Washington Street), as the former "Orange Street" also was the street that joined the city to the mainland through Boston Neck in colonial times;[50] the Green Line because it runs adjacent to parts of the Emerald Necklace park system; the Blue Line because it runs under Boston Harbor; and the Red Line because its northernmost station used to be at Harvard University, whose school color is crimson.[51]

The four transit lines all use standard rail gauge, but are otherwise incompatible; trains of one line would have to be modified to run on another. Orange and Blue Line trains are similar enough that modification of some Blue Line trains for operation on the Orange Line was considered, although ultimately rejected for cost reasons. Also, some of the new Blue Line cars from Siemens Transportation were tested on the Orange Line after hours, before acceptance for revenue service on the Blue Line. There are no direct track connections between lines, except between the Red Line and Ashmont-Mattapan High Speed Line, but all except the Blue Line have little-used connections to the national rail network, which have been used for deliveries of railcars and supplies.[52]

Opened in September 1897, the four-track-wide segment of the Green Line tunnel between Park Street and Boylston stations was the first subway in the United States, and has been designated a National Historic Landmark. The downtown portions of what are now the Green, Orange, Blue, and Red line tunnels were all in service by 1912. Additions to the rapid transit network occurred in most decades of the 1900s, and continue in the 2000s with the addition of Silver Line bus rapid transit and planned Green Line expansion. (See History and Future plans sections.)

In FY2005, there were on average 628,400 weekday boardings on the rapid transit and light rail lines (including the Silver Line Bus Rapid Transit), or 55.0% of the MBTA system.[48]

On January 29, 2014, the MBTA completed a countdown clock display system, alerting passengers to arriving trains, at all 53 heavy rail subway stations (the Red, Blue and Orange Lines). The MBTA expects to introduce countdown clocks in Green Line stations by the end of 2014.[53]

Commuter rail

The MBTA Commuter Rail system is a regional rail network that reaches from Boston into the suburbs of eastern Massachusetts. The system consists of twelve main lines, three of which have two branches. The rail network operates according to a spoke-hub distribution paradigm, with the lines running radially outward from the city of Boston. Eight of the lines converge at South Station, with four of these passing through Back Bay station. The other four converge at North Station. There is no passenger connection between the two sides; the Grand Junction Railroad is used for non-revenue equipment moves accessing the maintenance facility. The North–South Rail Link has been proposed to connect the two halves of the system; it would be constructed under the Central Artery tunnel of the Big Dig.

Special MBTA trains are run over the Franklin Line and the Providence/Stoughton Line to Foxborough station for New England Patriots home games and other events at Gillette Stadium. The CapeFLYER intercity service, operated on summer weekends, uses MBTA equipment and operates over the Middleborough/Lakeville Line. Amtrak runs regularly scheduled intercity rail service over four lines: the Lake Shore Limited over the Framingham/Worcester Line, Acela Express and Northeast Regional services over the Providence/Stoughton Line, and the Downeaster over sections of the Lowell Line and Haverhill Line. Freight trains run by Pan Am Southern, Pan Am Railways, CSX Transportation, the Providence and Worcester Railroad, and the Fore River Railroad also use parts of the network.

The first commuter rail service in the United States was operated over what is now the Framingham/Worcester Line beginning in 1834. Within the next several decades, Boston was the center of a massive rail network, with eight trunk lines and dozens of branches. By 1900, ownership was consolidated under the Boston and Maine Railroad to the north, the New York Central Railroad to the west, and the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad to the south. Most branches and one trunk line – the former Old Colony Railroad main – had their passenger services discontinued during the middle of the 20th century. In 1964, the MBTA was formed to subsidize the failing suburban railroad operations, with an eye towards converting many to extensions of the existing rapid transit system. The first unified branding of the system was applied on October 8, 1974, with "MBTA Commuter Rail" naming and purple coloration analogous to the four subway lines.[21] The system continued to shrink – mostly with the loss of marginal lines with one daily round trip – until 1981. The system has been expanded since, with four lines restored (Fairmount Line in 1979, Old Colony Lines in 1997, and Greenbush Line in 2007), six extended., and a number of stations added and rebuilt.

Several further expansions are planned or proposed. The South Coast Rail project, for which preliminary construction began in 2014, would extend the Stoughton section of the Providence/Stoughton Line to Taunton, with two branches to New Bedford and Fall River. Extensions of the Providence/Stoughton Line to Kingston, the Middleborough/Lakeville Line to Buzzards Bay, and the Lowell Line into New Hampshire are also proposed. Infill stations at Boston Landing, Blue Hill Avenue, West Station, and South Salem are under construction or planned.

Each commuter rail line has up to eleven fare zones, numbered 1A and 1 through 10. Riders are charged based on the number of zones they travel through. Tickets can be purchased on the train, from ticket counters or machines in some rail stations, or with a mobile app.[54] If a local vendor or ticket machine is available, riders will pay a surcharge for paying with cash on board. Fares range from $2.25 to $12.50, with multi-ride and monthly passes available.[55] In 2016, the system averaged 122,600 daily riders, making it the fourth-busiest commuter rail system in the nation.[56]

The MBTA commuter rail network was the first in the nation to offer free on-board Wi-Fi. It offers Wi-Fi-enabled coaches on all train sets.[57]

Ferries

The MBTA Boat system comprises several ferry routes via Boston Harbor. One of these is an inner harbor service, linking the downtown waterfront with the Boston Navy Yard in Charlestown. The other routes are commuter routes, linking downtown to Hingham, Hull, and Salem. Some commuter services operate via Logan International Airport.

All boat services are operated by private sector companies under contract to the MBTA. In FY2005, the MBTA boat system carried 4,650 passengers (0.41% of total MBTA passengers) per weekday.[48] The service is provided through contract of the MBTA by Boston Harbor Cruises (BHC) and Water Transportation Alternatives, Inc. (WTAI) under the name Boston's Best Cruises.

Paratransit

The MBTA contracts out operation of "The Ride", an on-demand pickup and dropoff service for people with mobility challenges. Paratransit services carry 5,400 passengers on a typical weekday, or 0.47% of the MBTA system ridership.[48][58] The three private service providers under contractual agreement with the MBTA for The Ride service are: Greater Lynn Senior Services (GLSS),[59] Veterans Transportation LLC,[60] and The Joint Venture of TTI/YCN, LLC.[61]

In September 2016, the MBTA announced that paratransit users would be able to get rides from transportation network companies Uber and Lyft. Riders would pay $2 for a pickup within a few minutes (more for longer trips worth more than $15) instead of $3.15 for a scheduled pickup the next day. The MBTA would pay $13 instead of $31 per ride ($46 per trip when fixed costs of The Ride are considered).[62]

Bicycles

Conventional bicycles are generally allowed on MBTA commuter rail, commuter boat, and rapid transit lines during off-peak hours and all day on weekends and holidays. However, bicycles are not allowed at any time on the Green Line, or the Ashmont–Mattapan High Speed Line segment of the Red Line. Buses equipped with bike racks at the front (including the Silver Line) may always accommodate bicycles, up to the capacity limit of the racks. The MBTA claims that 95% of its buses are now equipped with bike racks, except for trackless trolleys which still lack this capability.[63]

Due to congestion and tight clearances, bicycles are banned from Park Street, Downtown Crossing, and Government Center stations at all times.[63]

However, compact folding bicycles are permitted on all MBTA vehicles at all times, provided that they are kept completely folded for the duration of the trip, including passage through faregates. Gasoline-powered vehicles, bike trailers, and Segways are prohibited.[63]

No special permit is required to take a bicycle onto an MBTA vehicle, but bicyclists are expected to follow the rules and hours of operation. Cyclists under 16 years old are supposed to be accompanied by a parent or legal guardian. Detailed rules, and an explanation of how to use front-of-bus bike racks and bike parking are on the MBTA website.[63]

The MBTA says that over 95% of its stations are equipped with bike racks, many of them under cover from the weather. In addition, over a dozen stations are equipped with "Pedal & Park" fully enclosed areas protected with video surveillance and controlled door access, for improved security. To obtain access, a personally registered CharlieCard must be used. Registration is done online, and requires a valid email address and the serial number of the CharlieCard. All bike parking is free of charge.[63]

Parking

As of 2014, the MBTA operates park and ride facilities at 103 locations with a total capacity of 55,000 automobiles, and is the owner of the largest number of off-street paid parking spaces in New England.[64] The number of spaces at stations with parking varies from a few dozen to over 2,500. The larger lots and garages are usually near a major highway exit, and most lots fill up during the morning rush hour. There are some 22,000 spaces on the southern portion of the commuter rail system, 9,400 on the northern portion and 14,600 at subway stations. The parking fee ranges from $4 to $7 per day, and overnight parking (maximum 7 days) is permitted at some stations. Management for a number of parking lots owned by the MBTA is handled by LAZ Parking Limited, LLC.[65]

Customers parking in MBTA-owned and operated lots with existing cash "honor boxes" can pay for parking online or via phone while in their cars or once they board a train, bus, or commuter boat.[66][67] As of February 2014, the MBTA switched from ParkMobile to PayByPhone as its provider for mobile parking payments by smartphone.[64] Monthly parking permits are available, offering a modest discount. Detailed parking information by station is available online, including prices, estimated vacancy rate, and number of accessible and bicycle parking slots.[64]

As of 2014, the MBTA has a policy for electric vehicle charging stations in its parking spaces, but does not yet have such facilities available.[68]

From time to time the MBTA has made various agreements with companies that contribute to commuting options. One company the MBTA selected was Zipcar; the MBTA provides Zipcar with a limited number of parking spaces at various subway stations throughout the system.[69]

Hours of operation

Traditionally, the MBTA has stopped running around 1 am each night, despite the fact that bars and clubs in most areas of Boston are open until 2 am. Like nearly all subways worldwide, the MBTA's subway does not have parallel express and local tracks, so much rail maintenance is only done when the trains are not running. An MBTA spokesperson has said, "with a 109-year-old system you have to be out there every night" to do necessary maintenance.[70] The MBTA did experiment with "Night Owl" substitute bus service from 2001 to 2005, but abandoned it because of insufficient ridership, citing a $7.53 per rider cost to keep the service open, five times the cost per passenger of an average bus route.[71]

A modified form of the MBTA's previous "Night Owl" service was experimentally reinstated starting in the spring of 2014—this time, all subway lines were proposed to run until 3 am on weekends, along with the 15 most heavily used bus lines and the para-transit service "The Ride".[72][73]

Starting March 28, 2014, the late-night service began operation on a one-year trial basis, with service continuation depending on late-night ridership and on possible corporate sponsorship.[74] As of August 2014, late-night ridership was stable, and much higher than the earlier failed experimental service. However, it is still unclear whether and on what basis the program might be extended past its first year.[75] The extended hours program has not been implemented on the MBTA commuter rail operations.

In early 2016, the MBTA decided that Late-Night service would be canceled because of lack of funding. The last night for late-night service was on March 19, 2016. The last train left at 2 a.m. on March 19, 2016.

Ridership

| Average T Weekday Ridership (Red, Green, Orange, and Blue lines) | ||

|---|---|---|

| FY* | Ridership | ±% |

| 1964 | 386,700 | — |

| 1969 | 391,900 | +1.3% |

| 1970 | 385,693 | −1.6% |

| 1971 | 400,572 | +3.9% |

| 1973 | 359,681 | −10.2% |

| 1974 | 354,839 | −1.3% |

| 1975 | 341,086 | −3.9% |

| 1976 | 316,397 | −7.2% |

| 1977 | 345,255 | +9.1% |

| 1978 | 382,595 | +10.8% |

| 1979 | 387,353 | +1.2% |

| 1983 | 326,542 | −15.7% |

| 1984 | 338,192 | +3.6% |

| 1985 | 364,775 | +7.9% |

| 1986 | 378,817 | +3.8% |

| 1987 | 401,542 | +6.0% |

| 1988 | 378,166 | −5.8% |

| 1989 | 387,148 | +2.4% |

| 1990 | 416,887 | +7.7% |

| 1991 | 414,608 | −0.5% |

| 1992 | 412,366 | −0.5% |

| 1993 | 395,616 | −4.1% |

| 1995 | 404,298 | +2.2% |

| 1997 | 444,449 | +9.9% |

| 1999 | 590,942 | +33.0% |

| 2000 | 588,676 | −0.4% |

| 2001 | 659,500 | +12.0% |

| 2002 | 664,400 | +0.7% |

| 2003 | 656,400 | −1.2% |

| 2004 | 633,000 | −3.6% |

| 2005 | 617,300 | −2.5% |

| 2007 | 719,400 | +16.5% |

| 2008 | 733,637 | +2.0% |

| 2009 | 719,579 | −1.9% |

| 2010 | 719,933 | +0.0% |

| 2011 | 718,638 | −0.2% |

| 2012 | 752,700 | +4.7% |

| 2013 | 766,960 | +1.9% |

| 2014 | 788,400 | +2.8% |

| Sources:[76][77] | ||

During Fiscal Year 2013, the entire MBTA system had a typical weekday passenger ridership of 1,297,650. The MBTA's rapid transit lines (Red, Green, Orange, and Blue) accounted for 59% of all rides, buses accounted for 30%, and commuter rail accounted for 10% of all rides. The MBTA's ferries and paratransit accounted for the remaining 1% of rides.[78]

Passenger ridership has been steadily growing over the years, and between 2010 and 2013, the system saw passenger ridership grow 4.6% or an additional 57,000 daily passengers to the system.

| 2004 | 2007 | 2010 | 2013 | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid transit | |||||

| Red Line | 210,500 | 226,417 | 241,603 | 272,684 | +29.5% |

| Green Line | 212,550 | 237,410 | 236,096 | 227,645 | +7.1% |

| Orange Line | 154,350 | 216,183 | 184,961 | 203,406 | +31.8% |

| Blue Line | 55,600 | 50,515 | 57,273 | 63,225 | +13.7% |

| Commuter rail | |||||

| MBTA Commuter Rail | 143,092 | 140,825 | 132,720 | 129,075 | -9.8% |

| Bus & trolley | |||||

| MBTA bus & trolley (includes Silver Line) | 382,600 | 355,588 | 374,040 | 387,815 | +1.4% |

| Silver Line | 14,100 | 25,715 | 30,026 | 29,839 | +111.6% |

| Ferry | |||||

| MBTA boat | 4,674 | 4,900 | 4,372 | 4,464 | -4.5% |

| Paratransit and contracted bus | |||||

| The Ride | 8,740 | 9,823 | 9,376 | 9,336 | +6.8% |

| Total | 1,172,106 | 1,241,631 | 1,240,441 | 1,327,489 | +10.7% |

| Station | Passengers | Lines | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | South Station | 25,100 | Red Line, Silver Line, Commuter Rail |

| 2. | Downtown Crossing | 23,500 | Red Line, Orange Line, Silver Line |

| 3. | Harvard | 23,200 | Red Line |

| 4. | Park Street | 19,700 | Red Line, Green Line, Orange Line, Silver Line

note: use Park St. Downtown Crossing connection to access Orange Line and Silver Line |

| 5. | Back Bay | 18,100 | Orange Line, Commuter Rail |

| 6. | North Station | 17,100 | Orange Line, Green Line, Commuter Rail |

| 7. | Central | 16,500 | Red Line |

| 8. | Kendall/MIT | 15,400 | Red Line |

| 9. | Forest Hills | 15,200 | Orange Line, Commuter Rail |

| 10. | Copley | 14,000 | Green Line |

Funding

Fares and fare collection

The MBTA has various fare structures for its various types of service. The CharlieCard electronic farecard is accepted on the subway and bus systems, but not on commuter rail, ferry, or paratransit services. Passengers pay for subway and bus rides at faregates in station entrances or fareboxes in the front of vehicles; MBTA employees manually check tickets on the commuter rail and ferries.

Since the 1980s, the MBTA has offered discounted monthly passes on all modes for the convenience of daily commuters and other frequent riders. One-day and seven-day passes, intended primarily for tourists, are available for buses, subway, and inner harbor ferries.

The MBTA has periodically raised fares to match inflation and keep the system financially solvent. A substantial increase effective July 2012 raised public ire including an "Occupy the MBTA" protest. A transportation funding law passed in 2013 limits MBTA fare increases to 5% every two years.[82] A 5% fare increase effective July 1, 2014 was implemented.

Subway and bus

As of 1 July 2016, all subway trips (Green Line, Blue Line, Orange Line, Red Line, Ashmont-Mattapan Line, and the Waterfront section of the Silver Line) cost $2.25 for CharlieCard holders and $2.75 for CharlieTicket or cash payers.[83] Local bus and trackless trolley fares (including the Washington Street section of the Silver Line) are $1.70 for CharlieCard holders and $2.00 for others.[84] All transfers between subway lines are free with all fare media. Passengers using CharlieCards can transfer free from a subway to a bus, and from a bus to a subway for the difference in price ("step-up fare").[85] CharlieTicket holders can transfer free between buses, but not between subway and bus, except between rapid transit and the Washington Street section of the Silver Line.[85] Paying directly with cash is only available on buses, Green Line surface stops, and the Ashmont-Mattapan Line; a higher price is charged because it slows the process of boarding.

The MBTA operates "Inner Express" and "Outer Express" buses to suburbs outside the subway system. Inner Express bus trips cost $3.65 with a CharlieCard or $4.75 without; Outer Express trips cost $5.25 with and $6.80 without. Free transfers are available to the subway and local buses with a CharlieCard, and to local buses with a CharlieTicket.[84]

CharlieTickets are available from ticket vending machines in MBTA rapid transit stations. CharlieCards are not dispensed by the machines, but are available free of charge on request at most MBTA Customer Service booths in stations, or at the CharlieCard Store at Downtown Crossing station. As given out, the CharlieCards are "empty", and must have value added at an MBTA ticket machine before they can be used.

The fare system, including on-board and in-station fare vending machines, was purchased from German-based Scheidt and Bachmann, which developed the technology.[86] The CharlieCards were developed by Gemalto and later by Giesecke & Devrient.[87][88] In 2006 electronic fares replaced metal tokens, which had been used on and off on transit systems in Boston for over a century.

Until 2007, not all subway fares were identical - passengers were not charged for boarding outbound Green Line trains at surface stops, while double fares were charged for the outer ends of the Green Line "D" Branch and the Red Line Braintree Branch. As part of a general fare hike effective January 1, 2007, the MBTA eliminated these inconsistent fares.[89]

Subway and bus fare history

| Date | Subway | Bus | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | CharlieCard | Cash | CharlieCard | ||

| 1964 | $0.20 | N/A | $0.10 | N/A | [90] |

| 1968 | $0.25 | $0.20 | [90] | ||

| September 1975 | $0.25 | $0.25 | [90] | ||

| June 1980 | $0.50 | $0.25 | [90] | ||

| August 1981 | $0.75 | $0.50 | [90] | ||

| May 1982 | $0.60 | $0.50 | [90] | ||

| May 1989 | $0.75 | $0.50 | [91] | ||

| October 1991 | $0.85 | $0.60 | [92] | ||

| September 2000 | $1.00 | $0.75 | [93] | ||

| January 2004 | $1.25 | $0.90 | [93] | ||

| January 2007 | $2.00 | $1.70 | $1.50 | $1.25 | [94] |

| July 2012 | $2.50 | $2.00 | $2.00 | $1.50 | [95] |

| July 2014 | $2.65 | $2.10 | $2.10 | $1.60 | [96] |

| July 2016 | $2.75 | $2.25 | $2.00 | $1.70 | [97] |

Commuter Rail

Commuter rail fares are on a zone-based system, with fares dependent on the distance from downtown. Rides between Zone 1A stations - South Station, Back Bay, most of the Fairmount Line, and eight other stations within several miles of downtown - cost $2.10, the same as a subway fare with a CharlieCard. Fares for other stations range from $5.75 from Zone 1 (~5–10 miles from downtown) to $14.50 from Zone 10 (~60 miles). All Massachusetts stations are Zone 8 or closer; only T.F. Green Airport and Wickford Junction in Rhode Island are Zone 9 and 10.[98]

Interzone fares - for trips that do not go to Zone 1A - are offered at a substantial discount to encourage riders to take the commuter rail for less common commuting patterns for which transit is not usually taken. Discounted monthly passes are available for all trips; 10-ride passes at full price are also available for trips to Zone 1A. All monthly passes include unlimited trips on the subway and local bus; some outer-zone monthlies also offer free use of express buses and ferries. A cash-on-board surcharge of $3.00 is added for trips originating from stations with fare vending machines.[98]

MBTA Boat

The Inner Harbor Ferry costs $3.25 per ride, and is grouped as a Zone 1A monthly commuter rail pass. Single rides cost $8.50 from Hull or Hingham to Boston, $17.00 from Hull or Hingham to Logan Airport, and $13.75 from Boston to Logan Airport.[99]

The Ride

Fares on The Ride, the MBTA's paratransit program, are structured differently from other modes. Passengers using The Ride must maintain an account with the MBTA in order to pay for service. Fares are $3.00 for "ADA trips" originating within 0.75 miles (1.21 km) of fixed-route bus or subway service and booked in advance, and $5.00 for "premium trips" booked the same day, or originating further away.[100]

Discounted fares

Discounted fares (As of 1 July 2014, $1.05 for the subway and $0.80 for local buses) as well as discounted monthly local bus and subway passes are available to seniors over 65, and passengers who are permanently disabled who utilize a special photo CharlieCard (called "Senior ID" and "Transportation Access Pass", respectively). Holders of these passes are also entitled to 50% off the Commuter Rail. Passengers who are legally blind ride for free on all MBTA services (including express buses and the Commuter Rail) with a Blind Access Card.[101]

Children 11 and under ride for free with an adult, and students aged 12–17 receive a 50% discount on fares until 11 pm on school days. Student discounts require a Student CharlieCard issued through the holder's school and is good until around the time when school vacation begins.[101]

Budget

| Revenue Source | Amount (FY 2014 budget) |

|---|---|

| State Sales Tax | $799M |

| Fares | $569M |

| Municipal Assessments | $157M |

| Parking | $15.7M |

| Real Estate | $15.4M |

| Advertising | $14.2M |

| Federal government | $12M |

| Other | $160M |

| Interest | $1.5M |

| Utility reimbursement from tenants | $1.7M |

| Total | $1.75B |

Since the "forward funding" reform in 2000, the MBTA is funded primarily through 16% of the state sales tax excluding the meals tax (with minimum dollar amount guarantee), which is set at 6.25% statewide, and therefore equal to 1% of taxable non-meal purchases statewide.[102] The authority is also funded by passenger fares and formula assessments of the cities and towns in its service area (excepting those which are assessed for the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority). Supplemental income is obtained from its parking lots (reserved for passengers), renting space to retail vendors in and around stations, rents from utility companies using MBTA rights of way, selling surplus land and movable property, advertising on vehicles and properties, and federal operating subsidies for special programs.

The FY2014 budget includes $1.422 Billion for operating expenses and $443.8M in debt and lease payments.

The Capital Investment Program is a rolling 5-year plan which programs capital expenses. The draft FY2009-2014 CIP[103] allocates $3,795M, including $879M in projects funded from non-MBTA state sources (required for Clean Air Act compliance), and $299M in projects with one-time federal funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Capital projects are paid for by federal grants, allocations from the general budget of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (for legal commitments and expansion projects) and MBTA bonds (which are paid off through the operating budget).

The FY2010 budget was supplemented by $160 million in sales tax revenue when the statewide rate was raised from 5% to 6.25%, to avoid service cuts or a fare increase in a year when deferred debt payments were coming due.[104]

Capital improvements and planning process

The Boston Metropolitan Planning Organization is responsible for overall regional surface transportation planning. As required by federal law for projects to be eligible for federal funding (except earmarks), the MPO maintains a fiscally constrained 20+ year Regional Transportation Plan for surface transportation expansion, the current edition of which is called Journey to 2030. The required 4-year MPO plan is called the Transportation Improvement Plan.

The MBTA maintains its own 25-year capital planning document, called the Program for Mass Transportation, which is fiscally unconstrained. The agency's 4-year plan is called the Capital Improvement Plan; it is the primary mechanism by which money is actually allocated to capital projects. Major capital spending projects must be approved by the MBTA Board, and except for unexpected needs, are usually included in the initial CIP.

In addition to federal funds programmed through the Boston MPO, and MBTA capital funds derived from fares, sales tax, municipal assessments, and other minor internal sources, the T receives funding from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for certain projects. The state may fund items in the State Implementation Plan (SIP) - such as the Big Dig mitigation projects - which is the plan required under the Clean Air Act to reduce air pollution. (As of 2007, all of Massachusetts is designated as a clean air "non-attainment" zone.)

In 2005, the administration of then-governor Mitt Romney announced a long range transportation plan that emphasized repair and maintenance over expansion.

Due to the financial constraints on the MBTA budget, it is expected that funds for all further expansion projects will be funded with money outside the MBTA's budget. A state transportation bond bill is being used to fund the Green Line extension to Somerville and Medford, and planning for commuter rail service to Fall River and New Bedford.

Projects underway and future plans

Blue Line

There is a proposal to extend the Blue Line northward to Lynn, Massachusetts, with two potential extension routes having been identified. One proposed path would run through marshland alongside the existing Newburyport/Rockport commuter rail line, while the other would extend the line along the remainder of the BRB&L right of way.[105]

In addition, the MBTA has committed to designing an extension of the line's southern terminus westward to Charles/MGH, where it would connect with the Red Line.[106] This was one of the mitigation measures the Commonwealth of Massachusetts agreed to as part of the Big Dig.[107]

Green Line

To settle a lawsuit with the Conservation Law Foundation to mitigate increased automobile emissions from the Big Dig, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts agreed to extend the Green Line north to Somerville and Medford, two suburbs currently under-served by the MBTA. This plan starts at a relocated Lechmere Station, and terminates at College Avenue in Medford and Union Square in Somerville. The original settlement-imposed deadline was December 31, 2014.[108] There will be an expected daily ridership of 8,420.[109] After projected costs increased to $3 billion, the project was halted in 2015 and scaled back. The revised project is expected to serve passengers beginning in late 2021.[110]

Another mitigation project in the initial settlement was restoration of service on the "E" Branch between Heath Street and Arborway/Forest Hills. A revised settlement agreement resulted in the substitution of other projects with similar air quality benefits. The state Executive Office of Transportation promised to consider other transit enhancements in the Arborway corridor.[111]

Silver Line

The MBTA and MassDOT are building a new Silver Line route to Chelsea via East Boston and the Airport Blue Line station.[112] Four new Silver Line stations will be built in Chelsea—Eastern Avenue, Box District, Downtown Chelsea and Mystic Mall. A new Chelsea commuter rail station and transit hub will be constructed at the terminus of the new Silver Line route. Service is expected to begin in 2017.[113][114][115]

A planned Silver Line Phase III would have connected the two halves of the Silver Line via an underground busway from Boylston station on the Green Line to South Station. An initial proposed route involved a mile long tunnel connecting separate portals located at Charles and at Tremont streets.[116] As of 2014, planning of the Phase III tunnel has been suspended indefinitely, without any physical construction having begun, due to funding difficulties and community opposition.

Urban Ring

The Urban Ring is a project of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, to develop new public transportation routes that would provide improved circumferential connections among many existing transit lines that project radially from downtown Boston, allowing easier travel between locations outside of downtown. The project corridor passes through various neighborhoods of Boston, Chelsea, Everett, Malden, Medford, Somerville, Cambridge, and Brookline. The capital cost for this version of the plan is estimated at $2.2 billion, with a projected daily ridership of 170,000. Fifty-three percent of the route is either in a bus-only lane, dedicated busway, or tunnel.[117] The Urban Ring would have a higher collective ridership than the Orange Line, Blue Line, or the entire commuter rail system.[117]

Commuter rail

There are several proposed extensions to current commuter rail lines. An extension of the Stoughton Line is proposed to serve Fall River, and New Bedford.[118][119] Critics argue that building the extension does not make economic sense.[120]

A 20-mile (32 km) extension of the Providence Line past Providence to T. F. Green Airport and Wickford Junction in Rhode Island opened in 2012. The Rhode Island Department of Transportation is also studying the feasibility of serving existing Amtrak stations in Kingston and Westerly as well as constructing new stations in Cranston, East Greenwich, and West Davisville. Federal funding has also been provided for preliminary planning of a new station in Pawtucket.[121]

In September 2009, CSX Transportation and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts finalized a $100 million agreement to purchase CSX's Framingham to Worcester tracks, as well as some other track, to improve service on the Framingham/Worcester Line.[122] A liability issue that had held up the agreement[123][124] was resolved. There is also a project underway to upgrade the Fitchburg Line to have cab signaling and to construct a second track along a 7-mile (11 km) run near Acton which is shared with freight traffic, so that the Fitchburg to Boston trip will be able to take only about an hour. Completion is expected in December 2015.[125]

The state of New Hampshire created the New Hampshire Rail Transit Authority and allocated money to build platforms at Nashua and Manchester.[126] An article in The Eagle-Tribune claimed that Massachusetts was negotiating to buy property which has the potential to extend the Haverhill Line to Plaistow, New Hampshire.[127]

Massachusetts agreed in 2005 to make improvements on the Fairmount Line part of its legally binding commitment to mitigate increased air pollution from the Big Dig. These improvements, including four new infill stations, were supposed to be complete by December 31, 2011.[128] The total cost of the project was estimated at $79.4 million,[129] and it was expected to divert 220 daily trips from automobiles to transit.[130] As of March 2014, three of the new stations were open; the fourth station has been delayed by community opposition. In 2014, the MBTA announce it would purchase Diesel Multiple Unit (DMU) self-propelled rail cars for the Fairmount Line with eventual expansion to five other lines to be known as the Indigo Line.[131]

No direct rail connection exists between North Station and South Station, effectively splitting the commuter rail network into separate pieces. A North–South Rail Link has been proposed to unite the two halves of the commuter rail system, to allow more convenient and efficient through-routed service. However, because of high cost, Massachusetts withdrew its sponsorship of the proposal in 2006, in communications with the United States Department of Transportation. Advocacy groups continue to press for the project as a better alternative than expanding South Station, which would also be costly but provide fewer overall improvements in service.[132]

Management and administration

In 2015, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed new legislation creating a financial control board to oversee the MBTA.[133] The Fiscal and Management Control Board started meeting in July 2015 and is charged with bringing financial stability to the agency.[134] The Fiscal and Management Control Board reports to Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation Stephanie Pollack. Three of the five members of the MBTA Fiscal and Management Control Board are also members of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. The Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation leads the executive management team of MassDOT in addition to serving in the Governor's Cabinet. The MBTA's executive management team is led by its General Manager, who is currently also serving as the MassDOT Rail and Transit Administrator, overseeing all public transit in the state.[135]

The MBTA Advisory Board represents the cities and towns in the MBTA service district. The municipalities are assessed a total of $143M annually (as of FY2008). In return, the Advisory Board has veto power over the MBTA operating and capital budgets, including the power to reduce the overall amount.[136]

Key people

MassDOT Board of Directors

- Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation Stephanie Pollack (Chair)[137]

- Dominic Blue

- Ruth Bonsignore

- Lisa Calise

- Russell Gittlen

- Dean Mazzarella

- Robert Moylan, Jr.

- Steve Poftak

- Joseph Sullivan

- Betsy Taylor

- Monica Tibbits-Nutt

MBTA Fiscal and Management Control Board

- Joseph Aiello (Chair)[138]

- Lisa Calise

- Brian Lang

- Steve Poftak

- Monica Tibbits-Nutt

Other key people

- MBTA General Manager—Brian Shortsleeve (interim)

- MBTA Acting Chief Financial Officer- Michael Abramo[139]

- MBTA Chief Operating Officer-Jeffrey D. Gonneville

- MBTA Blue Line Deputy Director—Carolyne Daniels

- MBTA Green Line Deputy Director-Ted Timmons

- MBTA Orange Line Deputy Director—Tina Beasley

- MBTA Red Line Deputy Director—William McClellan

- MBTA Silver Line Deputy Director—Karen Burns

- Manager of Fixed Route Disability/Senior Services—Kathy Cox

- Customer Service Director—Carla Howze

- Director of Community Relations-Stephanie Neal-Johnson

- Director of Communications and Coordination-Darrin M. McAuliffe

General managers

- Edward Dana: 1947–1959

- Willis B. Downey (acting): 1959–1960

- Thomas McLernon: 1960–1965

- Otis M. Whitney: April 1–May 16, 1962 (Ran the MTA during a emergency period caused by a Carmen's strike)

- Rush B. Lincoln Jr.: 1965–1967

- Leo J. Cusick: 1967–1970

- Joseph C. Kelly (acting): 1970

- Joseph C. Kelly: 1970–1975

- Bob Kiley: 1975–1979 (as chairman/CEO)

- Robert Foster: 1979–1980 (as chairman/CEO)

- Barry Locke: 1980–1981 (as chairman/CEO)

- James O'Leary: 1981–1989

- Thomas P. Glynn: 1989–1991

- John J. Haley Jr.: 1991–1995

- Patrick Moynihan: 1995–1997

- Robert H. Prince: 1997–2001

- Michael H. Mulhern: 2002–2005

- Daniel Grabauskas: 2005–2009

- Richard A. Davey: 2010–2011

- Jonathan Davis (interim): 2011–2012

- Beverly A. Scott: 2012–2015

- Frank DePaola (interim): 2015–2016

- Brian Shortsleeve (acting): 2016–present

Major facilities and offices

The MBTA's buses are maintained and stored at several bus garages located throughout eastern Massachusetts:

- Albany Street, South End

- Cabot Garage, South Boston

- Arborway, Jamaica Plain

- Bartlett Garage (defunct, replaced by Arborway), Roxbury

- Charlestown Garage (two conjoined garages)

- Everett Main Repair Facility (also known as Everett Shops)

- Fellsway Garage, Medford

- Lynn Garage

- North Cambridge(trolley-buses only)

- Southampton Street Garage, South Boston (Silver Line, routes 28 and 39)

- Quincy Garage

Rail lines have their own maintenance facilities:

- Blue Line: Orient Heights Yard

- Green Line: Riverside Yard and Reservoir Yard

- Orange Line: Wellington Yard

- Red Line: Cabot Yard

Major administrative facilities:

- 10 Park Plaza (State Transportation Building), Boston

- 45 High Street, Boston

- MBTA Transit Police: 240 Southampton Street, Boston

- Senior & Transportation Access Pass (TAP) / Disability Office: CharlieCard Store, Downtown Crossing Station concourse (near Arch Street exit), Boston[140]

- Customer Service Window: CharlieCard Store, Downtown Crossing Station concourse, Boston[140]

- Revenue Operations: 32 Alford Street, Charlestown

Employees and unions

As of 2009, the MBTA employs 6,346 workers, of which roughly 600 are in part-time jobs.[141]

Structurally, the employees of the MBTA function as part of a handful of trade unions. The largest union of the MBTA is the Carmen’s Union (Local 589), representing bus and subway operators. This includes full and part-time bus drivers, motorpersons and streetcar motorpersons, full and part-time train attendants, and Customer Service Agents (CSAs). Further unions include the Machinists Union, Local 264; Electrical Workers Union, Local 717; the Welder's Union, Local 651; the Executive Union; the Office and Professional Employees International Union, Local 453; the Professional and Technical Engineers Union, Local 105; and the Office and Professional Employees Union, Local 6.

Within the authority, employees are ranked according to seniority (or "rating"). This is categorized by an employee's five-digit badge number, though some of the longest serving employees still have only four-digits. An employee's badge number indicates the relative length of employment with the MBTA; badges are issued in sequential order. The rating structure determines many different things, including the rank in which perks are to be offered to employee, such as: When offering the choice for quarter-annual route assignments ("picks"), overtime offerings, and even the rank to transfer new hires from part-time roles to a full-time role.

Law enforcement and security

The MBTA maintains its own police force which actively patrols all areas and vehicles used by the Authority. MBTA Police conduct routine vehicle patrol, routine foot patrol, incident investigations, and specialized patrol with K-9 dogs, and other specialized methods of explosive and narcotics detection.

The MBTA also maintains several closed-circuit television facilities located throughout its service area.[142] The cameras monitor various areas including trains stations, and MBTA vehicles throughout the system on a 24-hour basis. MBTA phone numbers pasted onto the front of the fare gates can place customers having a problem directly into contact with one of these operations centers.

Criticism

Fares and financial issues

Ahead of the MBTA's 2009 restructuring with the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), the MBTA had a total debenture of over US$8 billion.[143] As a direct result, MBTA fares and parking fees have increased significantly.[144] On July 1, 2012 MBTA fares went up as well as multiple service cuts, another fare hike took place on July 1, 2016

Rail vs. bus service

When the Orange Line was rebuilt in the 1980s, it was rerouted from deteriorating elevated railway structures to instead follow existing rail right-of-way, to greatly reduce land acquisition and construction costs. This had the side effect of changing its course away from the lower income areas of Everett, Chelsea, and Roxbury (where residents are less likely to own cars, and depend more on public transit), toward the more affluent towns of Malden and Medford, as well as sections of the Jamaica Plain neighborhood (where car ownership is higher, and thus, reliance on public transit is far lower).

To mitigate this, the MBTA set up a new bus line served by articulated buses equipped with specialized dispatching equipment, and a few of the features of a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) route. The MBTA named this new service the Silver Line, and classified it as though it were a high-capacity rail transit service, though it fails to meet full service standards for a BRT route. The Silver Line service has been criticized in many respects, most notably for its slow speed and the fact that it operates in mixed street traffic, subject to gridlock and collisions, earning it the nickname "Silver Lie" among some critics.[145] A rating from the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) determined that the MBTA Silver Line was best classified as "Not BRT" after local decision makers gradually decided to do away with most BRT-specific features.[146]:7,45

Radial vs. circumferential routes

Transportation advocates in Boston have complained that rail transit riders cannot travel from one outlying area to another without first traveling to the downtown hub stations, changing lines, and traveling outbound again. Some of the radial transit lines, notably the Green Line, are so overcrowded that service is very slow, unreliable, and capacity-limited because of rush-hour "crush loads". There are several crosstown bus lines, such as the #1, #66, CT1, CT2, and CT3 routes, but they are slow, unreliable, and subject to bus bunching because they must operate in mixed street traffic.

The MBTA Urban Ring Project would provide faster and more reliable circumferential service, and relieve overcrowding in the downtown hub stations. This issue has been studied as early as 1972, in the Boston Transportation Planning Review,[147] and has been in detailed planning stages since before 2000,[148] but has only been partially implemented due to lack of funding. A similar problem also occurs in the Washington Metro system, where customers cannot travel between suburbs on the same side of Washington without going through downtown, and Chicago's Metra and CTA systems, where all lines lead into and out of the central business district, rather than around it.

In popular culture

In 1951, the growing subway network was the setting of "A Subway Named Mobius", a science fiction short story written by the American astronomer Armin Joseph Deutsch. The tale described a Boston subway train which accidentally became a "phantom" by becoming lost in the fourth dimension, analogous to a topological Mobius strip.[149]:43[150] In 2001, a half-century later, the narrative was awarded a Retro Hugo Award for Best Short Story at the World Science Fiction Convention.[151]

In 1959, the satirical song "M.T.A." (informally known as "Charlie on the MTA") was a hit single, as performed by the folksingers the Kingston Trio. It tells the absurd story of a passenger named Charlie, who cannot pay a newly imposed 5-cent exit fare, and thus remains trapped in the subway system. The song was still well known in 2006, when the MBTA named its new electronic farecards the "CharlieCard" and "CharlieTicket".

See also

- Boston Street Railway Association

- David L. Gunn

- List of MBTA Subway stations

- List of metro systems

- List of United States rapid transit systems by ridership

- MBTA v. Anderson

- Noise mitigation

- Transit fares

- Transportation in Boston

References

- ↑ "MBTA-About the MBTA". Mbta.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "MBTA Silver Line". MBTA. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "MBTA Green Line". Mbta.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "MBTA Red Line". MBTA. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "MBTA Subway Map". MBTA. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2015" (pdf). American Public Transportation Association. March 2, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-15 – via http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Pages/ridershipreport.aspx.

- ↑ http://www.wbur.org/news/2016/05/23/mbta-frank-depaola-retire

- ↑ "About the T - Financials - Appendix: Statistical Profile" (PDF). MBTA. 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Ferry, J. Amanda (May 20, 2003). "Boston's subway". Boston.com. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ↑ Cudahy, Brian J. (2003). A Century of Subways: Celebrating 100 Years of New York's Underground Railways. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 167. ISBN 0-8232-2292-6.

- ↑ "Media Guide" (PDF). SEPTA. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ "Ridership rising fast, MBTA announces". Boston Globe. Boston.com. 6 June 2008. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ Wall, Lucas (1 August 2005). "T ridership reaches low point of decade". Boston.com. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- ↑ Daniels, Mac (13 March 2007). "T to tap reserves to balance budget". Boston Globe. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ Jonathan R. Davis (2 November 2007). "Joint Development and Intermodal Facilities" (PDF). Railvolution.org. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ "Creating a Sustainable Transportation & Energy Vision for the 21st Century" (Press release). mbta.com. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- 1 2 Cheney, Frank & Sammarco, Anthony M. (1999). Boston in Motion. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 7–9. ISBN 0738500879.

- ↑ "Famous Firsts in Massachusetts". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ↑ Boston's Green Line Crisis

- ↑ Humphrey, Thomas J. & Clark, Norton D. (1985). Boston's Commuter Rail: The First 150 Years. Boston Street Railway Association. p. 15. ISBN 9780685412947.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Belcher, Jonathan (22 March 2014). "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). NETransit. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ↑ Simon, James (January 18, 1982). "Suspended T official's trial starts". The Associated Press. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Barry Locke sentenced to 7–10 years in Walpole". Associated Press. February 17, 1982. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ Kindleberger, R.S. (March 20, 1984). "Locke Free, Vows to Aid Prison Reform in Mass.". Boston Globe. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ "T expansion on wrong track". The Boston Globe. May 24, 2006.

- ↑ "Legislators, Advocacy Groups And T Riders Call For MBTA Debt Relief". MASSPIRG. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "High hopes aboard as Greenbush commuter train gets rolling - The Boston Globe". Boston.com. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- ↑ Herald, Boston (2008-02-16). "Bus-ted: T lied to cut costs - BostonHerald.com". News.bostonherald.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ Boston Globe, May 29, 2008, "Fatal Crash On Green Line", pp. A1,A18.

- ↑ "Trolley Driver Was Texting Girlfriend At Time Of Crash: 46 Injured In Green Line Crash" Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine., WCVB, Boston, May 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Trolley Crash Inspires Tougher Cell Phone Policy: NTSB Still Investigating Crash". WCVB Boston. May 9, 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-02-22. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "Governor Patrick Signs Bill to Dramatically Reform Transportation System: New law will put an end to big dig culture, abolish the turnpike and help secure the commonwealth’s economic future". Press Release. Office of the Governor of Massachusetts. June 26, 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ↑ "Chapter 25 of the Acts of 2009: An Act Modernizing the Transportation Systems of the Commonwealth". Session Laws 2009. General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. June 29, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ↑ Bierman, Noah (January 15, 2009). "Senate roadway plan avoids tax or toll hike: Critics say concept ignores cash need". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ↑ Viser, Matt; Noah Bierman (June 18, 2009). "Legislature approves transportation bill despite union concerns". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ↑ Brownsberger, Will; State Representative; 24th Middlesex District (June 18, 2009). "Transportation Reform Enacted". WillBrownsberger.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ↑ Rocheleau, Matt (12 November 2012). "MBTA opens new commuter rail station at Talbot Avenue in Dorchester on Fairmount Line". Boston Globe. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ Spc. Michael V. Broughey, 65th Public Affairs Operations Center (April 24, 2013). "Soldiers deploy to MBTA subway stations following the Boston Marathon bombing | Article | The United States Army". Army.mil. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ↑ Shirley Leung (2013-04-19). "MBTA shutdown during hunt for Marathon bombing suspect irks commuters". Boston.com. Boston Globe. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- ↑ Bernstein, David S. (2013-04-22). "MBTA Buses Display 'Boston Strong' Messages". Bostonmagazine.com. Metrocorp, Inc. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

In a show of support for the families affected by the bombing, the T put up compassionate sayings.

- ↑ "Ridership and Service Statistics" (PDF) (14 ed.). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ "Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority, Regional Transit Authorities Coordination and Efficiencies Report" (PDF). Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ↑ Weinstock, Annie; et al. "Recapturing Global Leadership in Bus Rapid Transit" (PDF). Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

The majority of the [Boston] system lacks basic BRT features.

- ↑ Malouff, Dan (2013-05-17). "The US has only 5 true BRT systems, and none are "gold"". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Fare and Pass Information for Subway Service". MBTA.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "Schedules & Maps – Private Bus". MBTA. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ Cooke, Gilmore (November 10, 2004). "Power System of Boston’s Rapid Transit: Its Development, Historic Significance and Contributions". IEEE Milestone Presentation. Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Journey to 2030 Archived 2004-02-05 at the Wayback Machine.. Boston Metropolitan Planning Organization. May 2007. Chapter 2, p. 2-8. Refers to: MBTA, "Ridership and Service Statistics," Tenth Edition, 2006. Archived February 5, 2004, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Cambridge Seven Associates Website". C7a.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ↑ Vintage (early 1800s) map of Boston Neck, showing an "Orange Street" running SW to it from peninsular Boston of the 1770s

- ↑ Kleespies, Gavin W. & MacDonald, Katie. "Transportation History". Harvard Square Business Association. Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ↑ Discussion of rail intereconnections. The Red Line connection is at JFK/UMass, the Orange Line at Wellington (last used ca. 1981), and the Green Line at Riverside. Tractor trailer trucks may also be used to deliver train cars from the manufacturer. http://groups-beta.google.com/group/ne.transportation/browse_frm/thread/e6ba611be5abb7a/6c500ca982d60b28

- ↑ "Mbta announces completion of subway countdown clock system". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. January 29, 2014.

- ↑ "mTicket for Commuter Rail and Ferry". Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ↑ "Fare and Pass Information for Commuter Rail Service". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ↑ "Transit Ridership Report: Second Quarter 2016" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. August 22, 2016. p. 5.

- ↑ "Riding the T – Wi-Fi Commuter Rail Connect". MBTA. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "MBTA Paratransit Contractors Dispatch". Executive Office of Transportation. Archived from the original on 2012-02-23. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "Greater Lynn Senior Services". Glss.net. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "Veterans Transportation LLC". Handyline.veteranstheride.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "TTI/YCN Joint Venture, LLC (A joint venture of TTI and YCN Transportation, Inc.)". Jv-theride.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "MBTA Partners With Uber, Lyft To Improve Services For Riders With Disabilities". 16 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Bikes on the T". mbta.com. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved 2014-07-01.

- 1 2 3 "Parking". mbta.com. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved 2014-07-01.

- ↑ MBTA Press Release, November 19, 2007

- ↑ "MBTA Pay By Phone FAQs". Mbta.com. 2011-07-01. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "MBTA Pay-By-Phone website". Us.parkmobile.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "Electric Vehicle Charging Station Policy". mbta.com. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved 2014-07-01.

- ↑ "mbta.com". mbta.com. 2007-03-28. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "Fed Up". Boston Phoenix, January 19–25, 2007, p17.

- ↑ Tang, Lai-Yan. "Lights out for MBTA Night Owl bus routes". The Heights, March 17, 2005. Accessed 8 October 2009.

- ↑ Powers, Martine (December 4, 2013). "T’s late-night service plan could be arriving right on time". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ↑ "MBTA To Resume Late Night Service In The Spring". boston.cbslocal.com. CBSBoston. December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ↑ Annear, Steve (March 13, 2014). "Date Set For New Late-Night MBTA Service". Boston. Boston Magazine. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ↑ Powers, Martine (August 6, 2014). "MBTA says late-night ridership is steady". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ↑ "BART Ridership FY1964-FY2001" (PDF) (PDF). MBTA. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- ↑ "Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Statistics Presentation – Board of Directors" (PDF). MBTA. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Ridership and Service Statistics: Fourteenth Edition 2014" (PDF). MBTA. July 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ridership and Service Statistics: Thirteenth Edition 2010" (PDF). MBTA. July 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ridership and Service Statistics: Eleventh Edition 2007" (PDF). MBTA. October 2007. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "Service and Infrastructure Profile: July, 2005" (PDF). MBTA. Retrieved 21 January 2015.