Maria de Ergadia

Maria de Ergadia (died 1302) was a fourteenth-century Scottish noblewoman. She was Queen consort of Mann and the Isles and Countess of Strathearn.

Multiple marriages

Maria was a daughter of Eóghan Mac Dubhghaill, Lord of Argyll (died c.1268×1275), and thus a member of Clann Dubhghaill.[2]

She was married four times. Her successive husbands were: Magnús Óláfsson, King of Mann and the Isles (died 1265),[3] Maol Íosa II, Earl of Strathearn (died 1271),[4] Hugh, Lord of Abernethy (died 1291/1292),[5] and William FitzWarin (died 1299).[6] These unions appear to reveal the remarkable wide-ranging connections enjoyed by Clann Dubhghaill.[7]

It is unknown when Maria married her first husband.[8] Her father last appears on record in 1268, when he witnessed a charter of Maol Íosa. It is possible that this could have been about the time when Maria married him.[9] Within the same year, Maol Íosa is recorded to have owed a debt of £62 to the Scottish Crown,[10] a sum that could have been incurred as a result of the marriage.[11] The Earls of Strathearn were not amongst the Scottish realm's most wealthy magnates, and it is likely that Maol Íosa's marriage to the widow of the King of Mann and the Isles contributed to his wealth and enhanced his prestige.[12] Throughout much of her life, Maria bore the title Countess of Strathearn.[13]

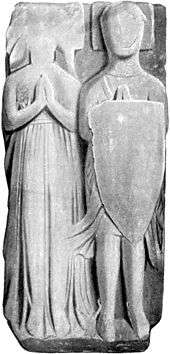

Maria and her third husband, Hugh, had several children.[14] One such child of her and Hugh was Alexander.[15] After Hugh's death, Maria was summoned to appear before parliament to answer regarding Alexander's rights to various lands.[16] In 1292, Maria was indebted to Nicholas de Meynell for 200 marks, part of the tocher of a daughter of hers.[17] When Maria rendered homage to Edward I, King of England in 1296, she styled herself "la Reẏne de Man".[18] In 1302, Maria died in London amongst her Clann Dubhghaill kin,[19] and was buried along with William in London's Greyfriars church.[20] An effigy of her second husband, and perhaps Maria herself, lies in Dunblane Cathedral.[1]

Citations

- 1 2 Holton (2017) pp. 196–197; Neville (1983a) p. 116; Brydall (1895) pp. 350, 351 fig. 14.

- ↑ Holton (2017) p. xviii fig. 2; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 94 tab. ii.

- ↑ Holton (2017) pp. xviii fig. 2, 140; Higgit (2000) p. 19; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Neville (1983a) p. 112; Paul (1911) p. 246; Paul (1902) pp. 19–20; Bain (1884) p. 124 § 508; Turnbull (1842) p. 109; Rymer; Sanderson (1816) p. 773; Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi (1814) p. 26.

- ↑ Holton (2017) pp. xviii fig. 2; Higgit (2000) p. 19; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Cowan (1990) p. 122; Neville (1983a) pp. 112–113; Cokayne; White (1953) pp. 382–383; Paul (1902) pp. 19–20; Bain (1884) pp. 124 § 508, 285 § 1117, 437 § 1642; Turnbull (1842) p. 109; Rymer; Sanderson (1816) p. 773; RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.).

- ↑ Beam (2008) p. 132 n. 59; McQueen (2002) pp. 148–149 n. 23; Higgit (2000) p. 19; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383; Paul (1911) pp. 246–247; Paul (1902) p. 19; Bliss (1893) p. 463; Theiner (1864) p. 125 § 277; The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1844) p. 446; Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi (1814) p. 26; PoMS, H2/152/1 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 38476 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.).

- ↑ Sellar (2004); Higgit (2000) p. 19; Watson (1991) p. 245; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383; Paul (1911) p. 247; Paul (1902) p. 20; Henderson (1898); Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Bain (1884) pp. 270 § 1062, 280 § 1104, 285 § 1117, 437 § 1642.

- ↑ Sellar (2004).

- ↑ Holton (2017) p. 141.

- ↑ Holton (2017) p. 144; Sellar (2000) p. 205; Neville (1983a) p. 112; Neville (1983b) pp. 98–100 § 53; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 382, 382 n. p; Paul (1911) p. 246, 246 n. 10; Lindsay; Dowden; Thomson (1908) pp. 86–87 § 96.

- ↑ Neville (1983a) pp. 112, 239.

- ↑ Neville (1983a) p. 112.

- ↑ Neville (1983a) p. 240.

- ↑ Neville (1983a) p. 113.

- ↑ Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383 n. a; Bliss (1893) p. 463.

- ↑ Beam (2008) p. 132 n. 59; McQueen (2002) p. 149 n. 23.

- ↑ Beam (2008) p. 132 n. 59; McQueen (2002) pp. 148–149, 149 n. 23; The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1844) p. 446; RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.).

- ↑ Neville (1983a) p. 113.

- ↑ Holton (2017) p. 140 n. 76; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Bain (1884) p. 212; Instrumenta Publica... (1834) p. 164; PoMS, H6/2/0 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 79965 (n.d.).

- ↑ Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Simpson; Galbraith (n.d.) p. 173 § 290.

- ↑ Higgit (2000) p. 19; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383; Kingsford (1915) p. 74.

References

Primary sources

- Bain, Joseph, ed. (1884). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 2, A.D. 1272–1307. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via Internet Archive.

- Bliss, WH, ed. (1893). Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 1 (pt. 2). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office – via Internet Archive.

- Instrumenta Publica Sive Processus Super Fidelitatibus Et Homagiis Scotorum Domino Regi Angliæ Factis, A.D. MCCXCI–MCCXCVI. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. 1834 – via Internet Archive.

- Kingsford, CL (1915). The Grey Friars of London: Their History with the Register of Their Convent and an Appendix of Documents. British Society of Franciscan Studies (series vol. 6). Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press – via Internet Archive.

- Lindsay, WA; Dowden, J; Thomson, JM, eds. (1908). Charters, Bulls and Other Documents Relating to the Abbey of Inchaffray: Chiefly From the Originals in the Charter Chest of the Earl of Kinnoull. Publications of the Scottish History Society (series vol. 56). Edinburgh: Scottish History Society – via Internet Archive.

- Neville, CJ (1983b). The Earls of Strathearn From the Twelfth to the Mid-Fourteenth Century, With an Edition of Their Written Acts (PhD thesis). Vol. 2. University of Aberdeen.

- "PoMS, H2/152/1". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "PoMS, H6/2/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 38476". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 79965". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi. Vol. 1. His Majesty King George III. 1814 – via Google Books.

- "RPS, 1293/2/10". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "RPS, 1293/2/10". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Rymer, T; Sanderson, R, eds. (1816). Fœdera, Conventiones, Litteræ, Et Cujuscunque Generis Acta Publica, Inter Reges Angliæ, Et Alios Quosvis Imperatores, Reges, Pontifices, Principes, Vel Communitates. Vol. 1 (pt. 2). London – via HathiTrust.

- Simpson, GG; Galbraith, JD, eds. (n.d.). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 5, (Supplementary) A.D. 1108–1516. Scottish Record Office – via Internet Archive.

- The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland. Vol. 1. 1844 – via HathiTrust.

- Theiner, A, ed. (1864). Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum Historiam Illustrantia. Rome: Vatican – via HathiTrust.

- Turnbull, WBDD, ed. (1842). Extracta E Variis Cronicis Scocie: From the Ancient Manuscript in the Advocates Library at Edinburgh. Edinburgh: The Abbotsford Club – via Internet Archive.

Secondary sources

- Beam, AG (2008). The Balliol Dynasty, 1210–1364. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978 1 904607 73 1 – via Google Books.

- Brydall, R (1895). "The Monumental Effigies of Scotland, From the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Vol. 29: 329–410.

- Cokayne, GE; White, GH, eds. (1953). The Complete Peerage. Vol. 12, part 1. London: The St Catherine Press.

- Cowan, EJ (1990). "Norwegian Sunset — Scottish Dawn: Hakon IV and Alexander III". In Reid, NH. Scotland in the Reign of Alexander III, 1249–1286. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. pp. 103–131. ISBN 0-85976-218-1.

- Henderson, TF (1898). "Strathearn, Malise". In Lee, S. Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 35–36 – via Internet Archive.

- Higgitt, J (2000). The Murthly Hours: Devotion, Literacy and Luxury in Paris, England and the Gaelic West. The British Library Studies in Medieval Culture. London: The British Library. ISBN 0-8020-4759-9 – via Google Books.

- Holton, CT (2017). Masculine Identity in Medieval Scotland: Gender, Ethnicity, and Regionality (PhD thesis). University of Guelph – via The Atrium.

- McQueen, AAB (2002). The Origins and Development of the Scottish Parliament, 1249–1329. University of St Andrews – via Research@StAndrews:FullText.

- Neville, CJ (1983a). The Earls of Strathearn From the Twelfth to the Mid-Fourteenth Century, With an Edition of Their Written Acts (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. University of Aberdeen.

- Paul, JB (1902). "The Abernethy Pedigree". The Genealogist. Vol. 18: 16–325, 73–378 – via Foundations For Medieval Genealogy.

- Paul, JB, ed. (1911). The Scots Peerage: Founded on Wood's Edition of Sir Robert Douglas's Peerage of Scotland, Containing an Historical and Genealogical Account of the Nobility of that Kingdom. Vol. 8. Edinburgh: David Douglas – via Internet Archive.

- Sellar, WDH (2000). "Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA. Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 187–218. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sellar, WDH (2004). "MacDougall, Ewen, Lord of Argyll (d. in or After 1268)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49384. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription required (help)).

- Watson, F (1991). Edward I in Scotland: 1296–1305 (PhD thesis). University of Glasgow – via Glasgow Theses Service.