Luo peoples

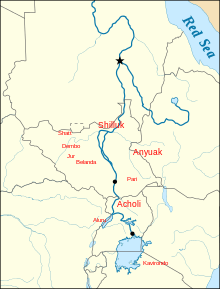

The Luo (also spelled Lwo) are several ethnically and linguistically related Nilotic ethnic groups in Africa that inhabit an area ranging from South Sudan and Ethiopia, through Northern Uganda and eastern Congo (DRC), into western Kenya, and the Mara Region of Tanzania. Their Luo languages belong to the Nilotic group and as such form part of the larger Eastern Sudanic family.

Luo groups in South Sudan include the Shilluk, Anuak, Pari, Acholi, Balanda Boor, Thuri, Maban, and Luo of Dimo, and those in Uganda include the Alur, Padhola, and Joluo.

The Joluo and their language Dholuo are also known as the "Luo proper", being eponymous of the larger group. The level of historical separation between these groups is estimated at about eight centuries. Dispersion from the Nilotic homeland in South Sudan was presumably triggered by the turmoils of the Muslim conquest of Sudan. The migration of individual groups over the last few centuries can to some extent be traced in the respective group's oral history.

Origins in South Sudan

The Luo (also Lwo) are part of the Nilotic group of people. The Nilote had separated from the other members of the East Sudanic family by about the 3rd millennium BC.[1] Within Nilotic, Luo forms part of the Western group.[2]

Within Luo, a Northern and a Southern group is distinguished. "Luo proper" or Dholuo is part of the Southern Luo group. Northern Luo is mostly spoken in South Sudan, while Southern Luo groups migrated south from the Bahr el Ghazal area in the early centuries of the second millennium AD (about eight hundred years ago).

A further division within the Northern Luo is recorded in a "widespread tradition" in Luo oral history:[3] the foundational figure of the Shilluk (or Chollo) nation was a chief named Nyikango, dated to about the mid-15th century. After a quarrel with his brother, he moved northward along the Nile and established a feudal society. The Pari people descend from the group that rejected Nyikango.[4]

Ethiopia

.jpg)

The Anuak are a Luo people whose villages are scattered along the banks and rivers of the southwestern area of Ethiopia, with others living directly across the border in South Sudan. The name of this people is also spelled Anyuak, Agnwak, and Anywaa. The Anuak of South Sudan live in a grassy region that is flat and virtually treeless. During the rainy season, this area floods, so that much of it becomes swampland with various channels of deep water running through it.

The Anuak who live in the lowlands of Gambela are distinguished by the color of their skin and are considered to be black Africans. The Ethiopian peoples of the highlands are of different ethnicities, and identify by lighter skin color. The Anuak have accused the current Ethiopian government and dominant highlands people of committing genocide against them. The government's oppression has affected the Anuak's access to education, health care and other basic services, as well as limiting opportunities for development of the area.

The Acholi, another Luo people in South Sudan, occupy what is now called Magwi County in Eastern Equatorial State. They border the Uganda Acoli of Northern Uganda. The South Sudan Acholi numbered about 10,000 on the 2008 population Census.

Uganda

Around 1500, a small group of Luo known as the Biito-Luo, led by Chief Labongo (his full title became Isingoma Labongo Rukidi, also known as Mpuga Rukidi), encountered Bantu-speaking peoples living in the area of Bunyoro. These Luo settled with the Bantu and established the Babiito dynasty, replacing the Bachwezi dynasty of the Empire of Kitara. According to Bunyoro legend, Labongo, the first in the line of the Babiito kings of Bunyoro-Kitara, was the twin brother of Kato Kimera, the first king of Buganda. These Luo were assimilated by the Bantu, and they lost their language and culture.

Later in the 16th century, other Luo-speaking people moved to the area that encompasses present day South Sudan, Northern Uganda and North-Eastern Congo (DRC) – forming the Alur, Jonam and Acholi. Conflicts developed when they encountered the Lango, who had been living in the area north of Lake Kyoga. The Lango also speak a Luo language. According to Driberg (1923), the Lango reached the eastern province of Uganda (Otuke Hills), having traveled southeasterly from the Shilluk area. The Lango language is similar to the Shilluk language. There is not consensus as to whether the Lango share ancestry with the Luo (with whom they share a common language), or if they have closer ethnic kinship with their easterly Ateker neighbours, with whom they share many cultural traits.

Between the middle of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century, some Luo groups proceeded eastwards. One group called Padhola (or Jopadhola - people of Adhola), led by a chief called Adhola, settled in Budama in Eastern Uganda. They settled in a thickly forested area as a defence against attacks from Bantu neighbours who had already settled there. This self-imposed isolation helped them maintain their language and culture amidst Bantu and Ateker communities.

Those who went further a field were the Joka jok and Joka owiny. The Jok Luo moved deeper into the Kaviirondo Gulf; their descendants are the present-day Jo Kisumo and Jo Rachuonyo amongst others. Jo owiny occupied an area near got ramogi or ramogi hill in alego of siaya district. The Owiny's ruins are still identifiable to this day at Bungu Owiny near Lake Kanyaboli.

The other notable Luo group is the Omolo Luo who inhabited Ugenya and gem areas of Siaya district. The last immigrants were the Jo Kager, who are related to the Omollo Luo. Their leader Ochieng Waljak Ger used his advanced military skill to drive away the Omiya or Bantu groups, who were then living in present-day Ugenya around 1750AD.

Kenya and Tanzania

Between about 1500 and 1800, other Luo groups crossed into present-day Kenya and eventually into present-day Tanzania. They inhabited the area on the banks of Lake Victoria. According to the Joluo, a warrior chief named Ramogi Ajwang led them into present-day Kenya about 500 years ago.

As in Uganda, some non-Luo people in Kenya have adopted Luo languages. A majority of the Bantu Suba people in Kenya speak Dholuo as a first language and have largely been assimilated.

The Luo in Kenya, who call themselves Joluo (aka Jaluo, "people of Luo"), are the fourth largest community in Kenya after the Kikuyu, Kalenjin and Luhya. In 2010 their population was estimated to be 4.1million. In Tanzania they numbered (in 2001) an estimated 980,000 . The Luo in Kenya and Tanzania call their language Dholuo, which is mutually intelligible (to varying degrees) with the languages of the Lango, Kumam and Padhola of Uganda, Acoli of Uganda and South Sudan and Alur of Uganda and Congo.

The Luo (or Joluo) are traditional fishermen and practice fishing as their main economic activity. Other cultural activities included wrestling (yii or dhao) kwath for the young boys aged 13–18 in their age sets. Their main rivals in the 18th century were luo Lango, the Highland Nilotes, who traditionally engaged them in fierce bloody battles, most of which emanated from the stealing of their livestock.

The Luo people of Kenya are nilotes and are related to the Nilotic people. The Luo people of Kenya are the are the fourth largest community in Kenya after the Kikuyu, Kenya, and, together with their brethren in Tanzania, comprise the second largest single ethnic group in East Africa. The Luo of Kenya do not share ancestry with the Luo tribes below.

This includes peoples who share Luo ancestry and/or speak a Luo language.

- Acoli (Uganda and Kenya)

- Acholi (South Sudan and Uganda)

- Alur (Uganda and DRC)

- Anuak (Ethiopia and South Sudan)

- Blanda Boore (South Sudan)

- Gambella (Ethiopia)

- Jopadhola (Uganda)

- Jonam (Uganda)

- Jumjum (South Sudan)

- Jurbel (South Sudan)

- Kumam (Uganda)

- Joluo (Kenya and Tanzania)

- Luo of Dimo (South Sudan)

- Pari (South Sudan)

- Shilluk (South Sudan)

- Thuri (South Sudan)

- Maban (South Sudan)

- Balanda Bwoor (South Sudan)

- Cope/Paluo people (Uganda)

Internationally notable Luo people

- Frank X, Kenyan Billionaire

- Peter Opiyo, Kenyan footballer

- Aamito Stacie Lagum, Ugandan international fashion model and winner of the first Africa's Next Top Model

- Adongo Agada Cham, 23rd King of the Anuak Nyiudola Royal Dynasty of Sudan and Ethiopia

- Ayub Ogada, singer, composer, and performer on the nyatiti, the Nilotic lyre of Kenya

- Barack Obama, 44th President of the United States, of partial Luo descent through his father, Barack Obama, Sr.

- Barack Obama, Sr., Economist, Harvard University Graduate, father of previous U.S. President Barack Obama (Kenyan)

- Bazilio Olara-Okello, Former Senior Army officer, deceased (Ugandan) who led the rebellion that gave Tito Okello the Presidency

- Betty Bigombe, Former Ugandan Politician, a senior fellow at the U.S Institute of Peace

- David Peter Simon Wasawo, University of Oxford trained Zoologist and the first African Deputy Principal of Makerere University College and Nairobi University College

- George Ramogi, musician (Kenya)

- Grace Ogot, Educationist (Kenya)

- Henry Luke Orombi, Archbishop of the church of Uganda

- Janani Luwum, Former Archbishop of the Church of Uganda

- Jaramogi Oginga Odinga - Independence Fighter, First Vice President of Independent Kenya

- Johnny Oduya, a defenseman for the Chicago Blackhawks of the NHL

- Joseph Kony, Leader of the Lord's Resistance Army, notorious rebel group in Uganda

- Kevin Ochieng Obura (Kenya), African and Luo Information System Expert

- Dennis Oliech,Football player, the most successful Kenyan footballer of his time[5]

- Dr. Lakareber Janet (Uganda), author, Acoli Accented Orthography ISBN 978-0954932305

- Lupita Nyong'o (Kenya), Actress and Filmmaker (Yale School of Drama)

- Matthew Lukwiya, Epidemiologist, died while fighting to eradicate the ebola pandemic in northern Uganda

- Okot p'Bitek, poet and author of the Song of Lawino (Uganda)

- Olara Otunnu, Former Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations and Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict

(Uganda)

- Raila Amolo Odinga, Second Prime Minister of Kenya

- Ramogi Achieng Oneko, Independence Freedom Fighter and Politician (Kenya)

- Robert Ouko, Kenyan Foreign Minister, murdered in 1990

- James Orengo, Senate Member in Kenya and a Senior Counsel in Kenya. He is also known for the Second Liberation fight in Kenyan politics

- Oburu Odinga, Former Kenyan Minister and Member of Kenyan Senate

- Thomas Odhiambo, Pre-eminent scientist, founder of International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, exceptional thinker, visionary and influencer (Kenya)

- Francis Ochola Orieny, Political editor (Kenya)

- Thomas Risley Odhiambo, University of Cambridge trained entomologist and environmental activist (Kenya), and the founder Director Of ICIPE, African Academy of Sciences and RANDFORUM

- Ruth Odinga, Kisumu Deputy Governor, younger sister to Raila Odinga and Daughter of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. (Kenya)

- Tito Okello, Former President of Uganda and Army Commander – Deceased

- Tom Mboya, politician, Pan-Africanist, assassinated in 1969 (Kenya)

- Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Author (Kenya)

- Allan Orimba, Philanthropist (Kenya)

- Paul Frohmiller Owiti, Activist (Kenya)

- D.O Owino misiani, Musician (Kenya/Tanzania)

- Ochieng Kabaselleh, Musician (Kenya)

- Musa Juma, Musician (Kenya)

- Omondi Tony, Musician (Kenya)

- Robert Jakech, ThoughtWorks Senior Quality Analyst (Uganda)[6]

- Dr John Alphonse Okidi, Senior Program Specialist - IDRC, Canada

- Isaac Okeyo, doctor at Egerton university

- Dr. Crispin Odhiambo Mbai, Former Chairman of the sub committee on devolution of power at the National Constitutional Conference of Kenya

- Apollo Milton Obote, former Ugandan President.

- Chris Musando, Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (Kenya) Deputy Director of ICT who was assassinated in July 2017.

Rev.Father Leopoldo Anywar,Founder of anyanya one rebellion in South Sudan.

References

- ↑ John Desmond Clark, From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa, University of California Press, 1984, p. 31

- ↑ Bethwell Ogot, History of the Southern Luo: Volume 1 Migration and Settlement.

- ↑ Conradin Perner, Living on Earth in the Sky, vol. 2 (1994), p. 135.

- ↑ Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster: Dualism, Centralism, and the Scapegoat King in Southeastern Sudan, BRILL (1992), p. 53.

- ↑ "The world's most wanted young players". The Guardian. 28 January 2004. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ https://www.thoughtworks.com/profiles/robert-jakech

External links

- Re-introducing the "People Without History"

- Towards a Human Rights Approach to Citizenship and Nationality Struggles in Africa

- The making of the Shilluk kingdom, A socio-political synopsis

- About Kenya

- The Luo

- History of the Anuak to 1956, by Professor Emeritus - Robert O. Collins.

- The pride of a people: Barack Obama, the ‘LUO’, lwanda magere)by Philip Ochieng, Nation Media Group, January, 2009.

Further reading

- Ogot, Bethwell A., History of the Southern Luo: Volume I, Migration and Settlement, 1500-1900, (Series: Peoples of East Africa), East African Publishing House, Nairobi, 1967

- Johnson D., History and Prophecy among the Nuer of Southern Sudan, PhD Thesis, UCLA, 1980

- Deng F.M. African of Two Worlds; the Dinka in Afro-Arab Sudan, Khartoum, 1978