Lunar: Eternal Blue

| Lunar: Eternal Blue | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) |

Game Arts Studio Alex |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Director(s) |

Yōichi Miyaji Hiroyuki Koyama |

| Producer(s) |

Kazutoyo Ishii Yōichi Miyaji |

| Designer(s) | Masayuki Shimada |

| Programmer(s) |

Hiroyuki Koyama Naozumi Honma Masao Ishikawa |

| Artist(s) |

Masatoshi Azumi Toshio Akashi Toshiyuki Kubooka |

| Writer(s) |

Kei Shigema Takashi Hino Toshio Akashi |

| Composer(s) | Noriyuki Iwadare |

| Series | Lunar |

| Platform(s) | Sega CD |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing video game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Lunar: Eternal Blue (ルナ エターナルブルー Runa Etānaru Burū) is a role-playing video game developed by Game Arts and Studio Alex for the Sega CD as the sequel to Lunar: The Silver Star. The game was originally released in December 1994 in Japan, and later in North America in September 1995 by Working Designs. Eternal Blue expanded the story and gameplay of its predecessor, and made more use of the Sega CD's hardware, including more detailed graphics, longer, more elaborate animated cutscenes, and more extensive use of voice acting. Critics were mostly pleased with the title, giving particular merit to the game's English translation and further expansion of the role-playing game genre in CD format.

Set one thousand years after the events of The Silver Star, the game follows the adventure of Hiro, a young explorer and adventurer who meets Lucia, visitor from the far-away Blue Star, becoming entangled in her mission to stop Zophar, an evil, all-powerful being, from destroying the world. During their journey across the world of Lunar, Hiro and Lucia are joined by an ever-expanding cast of supporting characters, including some from its predecessor. Eternal Blue was remade in 1998 as Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete.

Gameplay

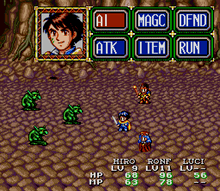

Lunar: Eternal Blue is a traditional role-playing video game featuring two-dimensional character sprites and backgrounds. The game is presented from a top-down perspective with players moving the characters across numerous fantasy environments while completing story-based scenarios and battling enemy monsters. While basic game function remains similar to Lunar: The Silver Star, with story segments being presented as both on-screen text and animated cutscenes, the abundance of these interludes has been increased to over fifty minutes of movie content and an hour of spoken dialogue. Players advance the story by taking part in quests and interacting with non-player characters, which engages them in the story as well as providing tips on how to advance.[1]

Battles in Eternal Blue take place randomly within dungeons and other hostile areas of the game. While in a battle sequence, players defeat enemy monsters either by using standard attacks or magic, with combat ending by defeating all enemies present. In order to attack an enemy, a character must first position themselves near their target by moving across the field, or by using a ranged attack to strike from a distance. The battle system has been enhanced from The Silver Star by including the option to position characters throughout the field beforehand, as well as a more sophisticated AI attack setting that allows the characters to act on their own.[2] Characters improve and grow stronger by defeating enemies, thereby gaining experience points that allow them to gain levels and face progressively more powerful enemies as the game advances. The player is awarded special "magic points" after combat that can be used to empower a particular character's magical attack, giving them access to new, more powerful skills with a variety of uses in and out of battle. Players can record their progress at any time during gameplay by saving to either the Sega CD's internal RAM, or on a separately purchased RAM cartridge that fits into the accompanying Sega Genesis.[3] In order to save at any time, magic experience points equal to Hiro's level × 15 is required.[4]

Plot

Characters

The character of Lunar; Eternal Blue were designed by artist and Lunar veteran Toshiyuki Kubooka.

- Hiro – a young man and would-be explorer who is skilled with a sword and boomerangs

- Ruby – a pink, winged cat-like creature with a crush on Hiro who claims to be a baby red dragon

- Gwyn – Hiro's adoptive grandfather, and an archaeologist

- Lucia – a mysterious and soft-spoken girl from the Blue Star who is skilled with magic and mostly naive of the world's customs

- Ronfar – a priest-turned-gambler with healing skills

- Lemina – money-grubbing heiress to the position of head of the world's highest magic guild

- Jean – a traveling dancer with a hidden past as a prisoner forced to use a deadly form of martial arts against innocent people

- Leo – captain of Althena's guard and servant of the goddess.[5]

While the cast's primary personalities remained intact for the English release, some changes such as colorful language, jokes, and double entendres were added to their speech to make the game more comical.

Primary supporting characters include the servants of the Goddess Althena, the creator of Lunar thought to have vanished centuries ago who suddenly appeared in mortal form to lead her people.

- Borgan – an obese, self-absorbed magician with his eyes on the seat of power in the magic guild

- Lunn – a martial artist and Jean's former instructor

- Mauri – Leo's sister and Ronfar's love interest.[6]

- Ghaleon – (the primary villain killed in the previous game) the current Dragonmaster, Althena's champion, and supposed protector of the world. His final end reveals that he regrets the evil he committed and does what he can to aid Hiro.

- Zophar – the game's principal villain, a long-dormant evil spirit who is attempting to destroy and recreate the world to his tastes. Although his voice is heard numerous times, he remains faceless until the final battle.[6]

Conception

The plot of Lunar: Eternal Blue was written by novelist Kei Shigema, who previously conceived the story for The Silver Star. Working together with new world-designer Hajime Satou, Shigema intended to craft a story that would continue where the previous game ended, while also giving players a thoroughly new experience that would elaborate on the history and mythos of the Lunar world.

Story

On Lunar, Hiro and Ruby are exploring an ancient ruin where they collect a large gem, The Dragon's Eye. Removing it sets off a trap and they flee as the temple collapses and monsters chase them. Despite rumours of a "destroyer" in the land, they and Gwyn investigate a strange light that hit the Blue Spire tower. They use the Dragon's Eye to access the tower where they meet Lucia, who asks to be taken to the goddess Althena to avert a disaster. Zophar, an evil disembodied spirit, drains Lucia of her magic powers, and the group convince former-priest Ronfar to heal her. Lucia then travels alone to find Althena.

Hiro, Ronfar and Ruby become concerned and follow Lucia, who they witness being abducted by Leo, the captain of Althena's guard. They rescue her and escape to a forest where they meet Jean, who helps them get to a town. Joined along the way by Lemina, the group travel across mountains and forests to reach Pentagulia, Althena's holy city. Lucia demands to see Althena but determines the woman is an imposter and, after a brief fight, the group are separated and thrown into dungeons. They are freed and joined by Leo, whose faith was shaken by Althena's recent actions. The group determine to thwart Ghaleon, the self-proclaimed Dragonmaster who is supporting the false Althena, by returning the power he took from the four dragons. In this quest, Lemina, Ronfar, Jean and Leo each confront one of Althena's heroes, redeeming themselves of their pasts.

The revived dragons, including Ruby, attack the false Althena's stronghold, where she is transformed into a demonic monster that the group defeat. At the pinnacle of the tower, they learn that the true Althena gave up her godhood after falling in love with a human. Lucia absorbs Althena's power in order to destroy Zophar, but hesitates as this could destroy all magic and Lunar itself. Lucia is captured by Zophar who drains her power, and she teleports Hiro and the others to safety. The group train to fight Zophar, and Ghaleon appears and gives Hiro his sword, explaining that he had to appear to be an enemy but wishes to atone for his past actions (i.e., as the villain of the first game).

The group work together and defeat Zophar with human strengths. Lucia then returns to the Blue Star, hoping she can one day entrust the Blue Star to humans based on what she witnessed on Lunar. Having fallen in love with Lucia, Hiro is heartbroken by her departure. In the epilogue, Hiro and the group reunite to help Hiro go to the Blue Star to be reunited with Lucia. Hiro succeeds, and the two look towards a bright future for humanity.

Development

Lunar: Eternal Blue was developed by Game Arts and Studio Alex, with project director Yoichi Miyagi returning to oversee the production of the new game. According to scenario writer Kei Shigema, the game's concept of an oppressive god came from the image of Sun Wukong, hero of the Chinese epic Journey to the West, being unable to escape from the gigantic palm of the Buddha.[7] Shigema stated that "it was a picture showing the arrogance of a god who is saying, 'In the end, you pathetic humans are in my hands.' The moment I understood that, I thought, 'Oh, I definitely want to do this,' it'll definitely match perfectly. So we used it just like that."[8] Eternal Blue took three years and over US$2.5 million to produce, and contains twice as much dialogue as its precessor.[9] The game's development team originally wanted the game to be set only a few years after The Silver Star, and would feature slightly older versions of the previous cast along with the new characters, yet discarded the idea when they thought the new cast would lose focus.[10] Like its predecessor, the game contains animated interludes to help tell the game's story, which were developed in-house with Toshiyuki Kubooka serving as animation director. While The Silver Star contained only ten minutes of partially voiced animation, Eternal Blue features nearly fifty minutes of fully voiced video content.[11]

The game's North American version was translated and published by Working Designs, who had previously produced the English release of The Silver Star. Headed by company president Victor Ireland, the game's script contains the same light humor of the original, with references to American pop culture, word play, and breaking of the fourth wall not seen in the Japanese version. Working closely with the staff at Game Arts, Working Designs implemented design and balance fixes into the American release, including altering the difficulty of some battles that were found to be "near impossible".[12] Finding little risk in the ability to save the game anywhere, Ireland's team added a "cost" component to the game's save feature, where players would have to spend points earned after battles to record their progress, remarking that "[We] wanted to make the player think about where and when to save without making it too burdensome."[13] In addition, Working Designs implemented the ability for the game to remember the last action selected by the player during combat, allowing them to use the same command the next round without having to manually select it.[9] Like The Silver Star, the North American version of Eternal Blue featured an embossed instruction manual cover.

Audio

The soundtrack for Lunar: Eternal Blue was composed by Noriyuki Iwadare, who had previously co-produced the music for Lunar: The Silver Star. The game utilizes studio-quality Red Book audio for one of the two vocal songs. (Both are CD tracks in the US version.) Every other piece of music was encoded into 16 kHz PCM files. Dialogue and certain ambient effects also used the PCM format. Most sound effects were generated through the Sega Genesis sound processor.[14] Along with music director Isao Mizoguchi, Iwadare's goal was to produce music that contained "a high degree of originality" when compared to both the previous game and role-playing games in general.[15] While the original game's music represented a number of styles and genres, Iwadare purposefully narrowed his range of composition to give the songs a unified feel.[15] The English version contains an original title not found in the Japanese release, named the "Star Dragon Theme". It was used as the BGM for the Star Tower dungeon.[11] The game's ending theme, "Eternal Blue ~Thoughts of Eternity~" (ETERNAL BLUE performed by Chisa Yokoyama, is one of Iwadare's favorite compositions.[16] An official soundtrack featuring selected tracks from the game was released in Japan on February 22, 1995 by Toshiba-EMI Records.[14]

| Lunar: Eternal Blue Original Soundtrack track list | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Lunar Eternal Blue ~Main Theme~" | 3:10 |

| 2. | "Adventure Road" (vocal by Hikaru Midorikawa as Hiro) | 4:09 |

| 3. | "Dragonship Bolgan" | 3:12 |

| 4. | "Zophar's Arrival" | 1:34 |

| 5. | "Town ~ Street" | 4:28 |

| 6. | "Lucia's Decent ~Thoughts of Sorrow~" | 3:06 |

| 7. | "Goddess Althena" | 3:08 |

| 8. | "Holy Port Pentgulia" | 2:35 |

| 9. | "Carnival" | 1:24 |

| 10. | "The Final Match Approaches" | 3:50 |

| 11. | "Promenade" | 4:38 |

| 12. | "Zophar's Revival" | 2:26 |

| 13. | "Field of Reaching for Tomorrow" | 2:22 |

| 14. | "Lucia vs. Zophar ~The Last Battle~" | 4:48 |

| 15. | "Farwell" | 3:09 |

| 16. | "Eternal Blue ~Thoughts of Eternity~" (vocal by Chisa Yokoyama as Lucia) | 6:03 |

| Total length: | 54:33 | |

Voice

| Voice actors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Character | Japanese[17] | English[17] |

| Hiro | Hikaru Midorikawa | Mark Zempel |

| Lucia | Chisa Yokoyama | Kelly Weaver |

| Ruby | Kumiko Nishihara | Jennifer Stigile |

| Ronfar | Ryōtarō Okiayu | Ned Schuft |

| Jean | Aya Hisakawa | Jennifer Stigile |

| Lemina | Megumi Hayashibara | Kathy Emme |

| Leo | Shinichiro Ohta | Ty Webb |

| Lunn | Masaharu Satō | Blake Dorsey |

| Borgan | Daisuke Kyouri | Dean Williams |

| Mauri | Kumiko Watanabe | Emmunah Hauser |

| Nall | Rica Matsumoto | Johnathon Esses |

| Althena | Shiho Niiyama | Katie Staeck |

| Ghaleon | Rokurō Naya | John Truitt |

| Zophar | Iemasa Kayumi | T. Owen Smith |

Lunar: Eternal Blue features spoken dialogue during cutscenes and specific points in the game's script. While The Silver Star contained only fifteen minutes of voiced content, Eternal Blue features over an hour and a half of pre-recorded speech.[18] The game's cast consists of fifteen voiced roles, with the original Japanese version featuring veteran anime and video game actors, including Rokurō Naya returning as Ghaleon. For the game's English version, Working Designs hired friends and staff of the game's production crew, many of whom had worked on previous projects with the company. John Truitt also reprises his role as Ghaleon, and is joined by a number of new cast members to the Lunar series, many of which would return in future games.[19]

The Japanese release of Eternal Blue was preceded by a spoken drama album called Lunar: Eternal Blue Prelude in June 1994 featuring the game's future voice cast performing skits and songs in-character to promote the game.[20] When the game was released the following December, it was packaged with an 8 cm music disc called the Lunar: Eternal Blue Premium CD featuring short conversations by Lucia and Lemina, as well as in-character theme songs.[21] In the months following the game's release, a two-volume drama album set featuring an expanded cast titled Lunatic Parade would be released by Toshiba-EMI records in June[22] and September 1995.[23]

| Lunar: Eternal Blue Prelude track list | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Prologue: Eternal Blue Prologue" | 8:16 |

| 2. | "Chapter One: Sea of Sand" | 4:14 |

| 3. | "Chapter Two: Oasis" | 8:12 |

| 4. | "Chapter Three: Ghost Valley" | 4:25 |

| 5. | "Chapter Four: Ghost" | 3:20 |

| 6. | "Chapter Five: Camp" | 3:41 |

| 7. | "Althena's Song – Distant Journey" (vocal by Kikuko Inoue as Luna) | 6:34 |

| 8. | "Chapter Six: Black Knight" | 5:59 |

| 9. | "Ending" | 1:52 |

| 10. | "Lucia's Image Song – Rondo of Light and Shadow" (vocal by Chisa Yokoyama as Lucia) | 5:07 |

| 11. | "Epilogue – Prologue Reprise" | 5:29 |

| Total length: | 54:33 | |

| Lunar: Eternal Blue Premium CD track list | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Lucia and Lemina's Conversation 1" | |

| 2. | "Money is #1" (vocal by Megumi Hayashibara as Lemina) | 3:37 |

| 3. | "Lucia and Lemina's Conversation 2" | |

| 4. | "Eternal Blue ~Eternal Sentiment~" (vocal by Chisa Yokoyama as Lucia) | 6:08 |

| 5. | "Lucia and Lemina's Conversation 3" | |

| Total length: | 16:12 | |

| Lunar: Eternal Blue Lunatic Parade Vol. 1 track list | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Lunatic Parade" | 4:30 |

| 2. | "Chapter One: Burning Determination" | 6:59 |

| 3. | "Lone Wolf Knight Leo" | 2:47 |

| 4. | "Rise Up Men of Valor! Battle No. 1" | 3:03 |

| 5. | "Chapter Two: The Magic Guild's Hair Crisis!" | 17:50 |

| 6. | "Money is #1" (vocal by Daisuke Gouri as Borgan & Megumi Hayashibara as Lemina) | 3:37 |

| 7. | "Martial Arts Tournament" | 2:22 |

| 8. | "Chapter Three: Hope's Second Chance!" | 9:01 |

| 9. | "Victory Teacher Ronfar" | 2:27 |

| 10. | "The Four Heroes" | 4:11 |

| 11. | "Chapter Four: Ghaleon's Last Moments" | 2:33 |

| Total length: | 59:25 | |

| Lunar: Eternal Blue Lunatic Parade Vol. 2 track list | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "The Envoy of Justice, The Masked White Knight Appears!!" | 4:25 |

| 2. | "Chapter Five: First Kiss" | 11:18 |

| 3. | "Love Love Funny" (vocal by Kumiko Nishihara as Ruby) | 4:55 |

| 4. | "I am the Great Nall!!" | 2:38 |

| 5. | "Chapter Six: Heart-Pounding, Happy, Bashful First Date!" | 16:43 |

| 6. | "Jean" | 2:50 |

| 7. | "Martial Arts Investigation" | 3:34 |

| 8. | "Fierce Fighting – Battle No. 2" | 3:10 |

| 9. | "Chapter Seven: Discussion of Lucia's Life!" | 10:39 |

| 10. | "Honky-Tonk Lucia" | 2:55 |

| Total length: | 63:21 | |

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lunar: Eternal Blue sold well in Japan despite an estimated retail price of JPY¥9,900, nearly the equivalent of US$100 in 1994.[9] The game would go on to sell fewer copies than its predecessor, Lunar: The Silver Star, yet still became the second-highest selling Sega-CD game in Japan and third highest selling worldwide.[33] Eternal Blue received a score of 30 out of 40 in Japanese magazine Megadrive Beep!,[34] with fellow Sega publication Megadrive Fan calling the game "fun" and featuring an official manga strip written by scenario writer Kei Shigema over the next several months.[35]

The game experienced relatively low sales during its release in North America, which Victor Ireland attributed to both the rise of 32-bit game consoles such as the Sega Saturn and PlayStation, and widespread media declaration of the Sega-CD's "death" in the video game market in 1995.[13] Its English release met with a favorable response, with GamePro remarking that "Eternal Blue could appear to some as 'just another RPG,' but the epic scope, appealing characters, and excellent cinematics make it much more," yet found the game's linear story progression to be its low point.[29] Electronic Gaming Monthly praised the game's "great story and witty characters", adding that "the all-important, usually absent ingredient is there: fun".[26] They awarded it as the Best Sega Mega-CD Game of 1995.[36] In their review, Game Players found the game's larger scope and expanded features made it less enjoyable than its predecessor, saying "it's a better game, it's just not quite as much fun. [We] still liked it, a lot, and it's definitely recommended, but it feels like something's been lost."[30] Next Generation Magazine echoed this sentiment, remarking that "overall it's a much stronger game, but you can't help feeling something missing", yet maintained that the game's storyline was "decidedly less goofy, with more of an emphasis on drama and storyline."[31]

When asked if he approved of the game's reviews, Ireland replied that they were "overall in the ballpark" from what he expected, with the exception of a portion of a review from GameFan.[13] In an earlier preview of the English version, editors of GameFan called the game's translation "ingeniously written",[37] which was later quoted in an Eternal Blue print advertisement that appeared in several magazines up to the game's release. When the editors reviewed the final version, however, they questioned the game's frequent use of jokes and lewd quips in place of the original Japanese narrative[27] which Ireland described as "a complete about-face"[13] Despite their problems with portions of the translation, the magazine would still regard the majority of the game's "non-joke-laden" script as "excellent", and awarded the game an above-average 91% rating, calling it "one of the greatest epics ever programmed".[27] Retro Gamer included Eternal Blue among top ten Mega CD games.[38]

Legacy

In July 1998, Game Arts and Japan Art Media released a remake to Eternal Blue, Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete for the Sega Saturn, with a PlayStation version available the following year. Like the remake of The Silver Star, Lunar: Silver Star Story Complete, the new version of Eternal Blue features updated graphics, re-arranged audio, and more robust animated sequences by Studio Gonzo, as well as an expanded script.[39] This version would be released in North America in 2000 once again by Working Designs in the form of an elaborate collector's edition package that includes a soundtrack CD, "making of" bonus disc, game map, and a special omake box complete with Eternal Blue collectibles.[40]

References

- ↑ Working Designs (1995). Lunar: The Silver Star instruction manual. Working Designs. p. 13. T-127045.

- ↑ Working Designs (1995). Lunar: The Silver Star instruction manual. Working Designs. p. 2627. T-127045.

- ↑ Working Designs (1995). Lunar: The Silver Star instruction manual. Working Designs. p. 15. T-127045.

- ↑ http://www.gamefaqs.com/segacd/587964-lunar-eternal-blue/faqs/5247#1._HEADING_HOME

- ↑ J. Douglas Arnold & Zach Meston (1995). Lunar: Eternal Blue – The Official Strategy Guide. Sandwich Islands Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 1-884364-07-1.

- 1 2 J. Douglas Arnold & Zach Meston (1995). Lunar: Eternal Blue – The Official Strategy Guide. Sandwich Islands Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 1-884364-07-1.

- ↑ Game Arts (1997). Lunar I & II Official Design Material Collection. Softbank. p. 90. ISBN 4-89052-662-5.

- ↑ Game Arts (1997). Lunar I & II Official Design Material Collection. Softbank. p. 91. ISBN 4-89052-662-5.

- 1 2 3 Working Designs (1995). Lunar: The Silver Star instruction manual. Working Designs. p. 37. T-127045.

- ↑ Working Designs (2000). Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete Instruction Manual. Working Designs. p. 7. SLUS-01071/01239/01240.

- 1 2 "Victor Ireland on Lunar 2". IGN. 2000-11-10. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ Working Designs (2000). Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete – The Official Strategy Guide. Working Designs. p. 219. ISBN 0-9662993-3-7.

- 1 2 3 4 J. Douglas Arnold & Zach Meston (1995). Lunar: Eternal Blue – The Official Strategy Guide. Sandwich Islands Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 1-884364-07-1.

- 1 2 Walton, Jason (2000-09-28). "Lunar: Eternal Blue OST". RPGFan. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- 1 2 Working Designs (2000). Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete Instruction Manual. Working Designs. p. 43. SLUS-01071/01239/01240.

- ↑ "Interview with Noriyuki Iwadare". LunarNET. April 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- 1 2 Shannon, Mickey. "Lunar Silver Star Story Complete Game Credits". LunarNET. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ↑ "Working Designs Museum > Lunar: Eternal Blue". Working Designs. 2004. Archived from the original on 2004-12-06. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Working Designs (2000). The Making of Lunar: Silver Star Story Complete. Working Designs. SLUS-01071/01239/01240.

- ↑ MagicEmporerNash (2000-03-12). "Lunar: Eternal Blue Prelude". RPGFan. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Gann, Patrick (2005-07-18). "Lunar: Eternal Blue Premium CD". RPGFan. Retrieved 2005-09-28.

- ↑ Gann, Patrick (2005-02-09). "Lunar: Eternal Blue Lunatic Parade Vol.1". RPGFan. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Bronzan, Brendan (2005-07-18). "Lunar: Eternal Blue Lunatic Parade Vol.2". RPGFan. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- 1 2 "Lunar: Eternal Blue Reviews". GameRankings. 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ "Lunar: Eternal Blue > Overview". Allgame. 1998. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- 1 2 Andrew Baran; Daniel Carpenter & Al Manuel (October 1995). "Lunar: Eternal Blue review". Electronic Gaming Monthly. San Francisco, California: Ziff Davis Media (75): 33. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004.

- 1 2 3 Nick Rox; E. Storm; Tahaki (October 1995). "Lunar: Eternal Blue review". GameFan. DieHard Gamers Club (36). Archived from the original on November 26, 2004.

- ↑ Paul Anderson, Andy McNamara & Andrew Reiner (August 1995). "Lunar: Eternal Blue review". Game Informer. GameStop Corporation (48). Archived from the original on November 26, 2004.

- 1 2 Major Mike (November 1995). "Lunar: Eternal Blue review". GamePro. DieHard Gamers Club (86): 120. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004.

- 1 2 Editors of Game Players (October 1995). "Lunar: Eternal Blue review". Game Players. Imagine Media (77). Archived from the original on November 26, 2004.

- 1 2 Editors of Next Generation (October 1995). "Lunar: Eternal Blue review". Next Generation. Imagine Media (10). Archived from the original on November 26, 2004.

- ↑ GhaleonOne (1998-03-17). "Lunar: Eternal Blue". RPGFan. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- 1 2 Pettus, Sam (2004). "Sega CD: A Console too Soon". Sega-16. Archived from the original on 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ "New Game Review". Megadrive Beep! (in Japanese). Tokyo, Japan: 23. January 1995.

- ↑ Working Designs (2000). Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete – The Official Strategy Guide. Working Designs. p. 143. ISBN 0-9662993-3-7.

- ↑ "Electronic Gaming Monthly's Buyer's Guide". 1996.

- ↑ Editors of GameFan (June 1995). "Previews: Lunar Eternal Blue". GameFan. DieHard Gamers Club (32).

- ↑ http://www.retrogamer.net/top_10/top-ten-mega-cd-games/

- ↑ Shoemaker, Brad (2001-01-03). "Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Cleveland, Adam (2000-11-16). "Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete Review". IGN. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

External links

- Official website at Working Designs (archived)

- Lunar: Eternal Blue at MobyGames

- Lunar: Eternal Blue at LunarNET