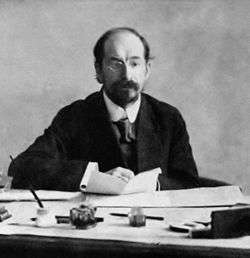

Anatoly Lunacharsky

| Anatoly Lunacharsky Анато́лий Лунача́рский | |

|---|---|

| |

| People's Commissars for Education | |

|

In office 26 October 1917 – September 1929 | |

| Prime Minister |

Vladimir Lenin Aleksei Rykov |

| Preceded by | Sergei Salazkin |

| Succeeded by | Andrei Bubnov |

| Soviet Ambassador to Spain | |

|

In office 1933–1933 | |

| President | Mikhail Kalinin |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky 23 November [O.S. 11 November] 1875 Poltava, Russian Empire |

| Died |

26 December 1933 (aged 58) Menton, Alpes-Maritimes, France |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party |

Bolshevik (1903-1933) Mezhraiontsy (1917) |

| Alma mater | University of Zurich |

| Occupation | Journalist |

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (Russian: Анато́лий Васи́льевич Лунача́рский, Ukrainian: Анатолій Васильович Луначарський, 23 November [O.S. 11 November] 1875 – 26 December 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and the first Soviet People's Commissar of Education responsible for culture and education. He was active as an art critic and journalist throughout his career.

Early life

Lunacharsky was born in Poltava, Ukraine, Russian Empire. He was an illegitimate child of Alexander Antonov and Alexandra Lunacharskaya, née Rostovtseva. His mother was then married to statesman Vasily Lunacharsky, which gave Anatoly's surname and patronym. Alexandra later divorced Lunacharsky and married Antonov, but Anatoly kept his old name.

Marxist politics

Lunacharsky became a Marxist at 15. He studied at the University of Zurich, under Avenarius, for two years without taking a degree. In Zürich, he met European socialists including Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. In February 1902, Lunacharsky moved in with Alexander Bogdanov who was working in a mental hospital in Vologda. By September, he married Anna Alexandrovna Malinovkaya, Bogdanov's sister.

In 1903, the party split into Bolsheviks led by Vladimir Lenin and Mensheviks led by Julius Martov; Lunacharsky sided with the former. In 1907, he attended the International Socialist Congress, held in Stuttgart. When the Bolsheviks, in turn, split into Lenin's supporters and Alexander Bogdanov's followers in 1908, Lunacharsky supported his brother-in-law, Bogdanov, in setting up Vpered. Like many contemporary socialists (including Bogdanov), Lunacharsky was influenced by the empirio-criticism philosophy of Ernst Mach and Avenarius. Lenin opposed Machism as a form of subjective idealism and strongly criticised its proponents in his book Materialism and Empirio-criticism (1908). In 1909, Lunacharsky joined Bogdanov and Gorky at the latter's villa on the island of Capri, where they started a school for Russian socialist workers. In 1910, Bogdanov, Lunacharsky, Mikhail Pokrovsky and their supporters moved the school to Bologna, where they continued teaching classes through 1911. In 1913, Lunacharsky moved to Paris, where he started his own "Circle of Proletarian Culture".

World War I

After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Lunacharsky adopted an internationalist antiwar position, which put him on a course of convergence with Lenin and Leon Trotsky. In 1915, Lunacharsky and Pavel Lebedev-Poliansky restarted the social democratic newspaper Vpered, with an emphasis on proletarian culture.[1]

After the February Revolution of 1917, Lunacharsky returned to Russia and, like other internationalist social democrats returning from abroad, briefly joined the Mezhraiontsy before they merged with the Bolsheviks in July and August 1917.

People's Commissariat for Education

After the October Revolution of 1917, Lunacharsky was appointed as People's Commissariat for Education in the first Soviet government and remained in that position, which put him in charge of education among other things. The New York Times reported his resignation in 1921.[2] Lunacharsky was associated with the establishment of the Bolshoi Drama Theater in 1919, working with Maxim Gorky, Alexander Blok and Maria Andreyeva. He was also in charge of the Soviet state's first censorship system. Lunacharsky helped his former colleague, Alexander Bogdanov, start a semi-independent proletarian art movement, Proletkult. Lunacharsky also oversaw improvements in Russia's literacy rate. By arguing for their architectural Importance, he argued for the protection of historic buildings against elements in the Bolshevik Party who wanted to destroy them.

League of Nations representative and ambassador to Spain

In 1930 Lunacharsky represented the Soviet Union at the League of Nations and in 1933 he was appointed ambassador to Spain. Lunacharsky died in Menton, France, en route to take up his post as the Soviet ambassador to Spain.[3]

Legacy

Lunacharsky's remains were returned to Moscow where his urn was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, a rare privilege during the Soviet era. During the Great terror of 1936-1938, Lunacharsky's name was erased from the Communist Party's history and his memoirs were banned.[4] A revival came in the late 1950s and 1960s, with a surge of memoirs about Lunacharsky and many streets and organizations named or renamed in his honor. During that era, Lunacharsky was viewed by the Soviet intelligentsia as an educated, refined, and tolerant Soviet politician.

Some Soviet-built orchestral harps also bear the name of Lunacharsky, presumably in his honor. These concert pedal harps were produced in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg, Russia).

Literary output

Lunacharsky was also a prolific writer. He wrote literary essays on the works of several writers, including Alexander Pushkin, George Bernard Shaw and Marcel Proust. His most notable work, however, is his memoirs, "Revolutionary Silhouettes", which describe anecdotes and Lunacharsky's general impressions of Lenin, Trotsky and eight other revolutionaries. Trotsky reacted to some of Lunacharsky's opinions in his own autobiography, "My Life."

Personal characteristics

Lunacharsky was known as an art connoisseur and a critic. He had been interested in philosophy, not only Marxist dialectics, since he was a student. For instance, he was fond of the ideas of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Frederich Nietzsche and Richard Avenarius.[5] He could read six modern languages and two dead ones. Lunacharsky corresponded with H. G. Wells, Bernard Shaw, and Romain Rolland.

Bibliography

- Self-Education of the Workers: The Cultural Task of the Struggling Proletariat, (1918) London: The Workers’ Socialist Federation

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, New Myth, New World: From Nietzsche to Stalinism, Pennsylvania State University, 2002, p.85 ISBN 0-271-02533-6

- ↑ "The New York Times: Wednesday January 5, 1921". Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ Stuart Brown; Diane Collinson; Robert Wilkinson (1 September 2003). Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Philosophers. Taylor & Francis. pp. 481–. ISBN 978-0-203-01447-9.

- ↑ Roy Medvedev, Let History Judge, 1971.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

Further reading

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila (1970). The Commisariat of Enlightenment: Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts under Lunacharsky. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52438-5.

- Works by Lunacharsky at Marxist internet archive

- Robert C Williams, 'From Positivism to Collectivism: Lunarcharsky and Proletarian Culture', in Williams, Artists in Revolution, Indiana University Press, 1977

- Vasilisa the Wise (A play by Lunacharsky, in English)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anatoliy Lunacharskiy. |