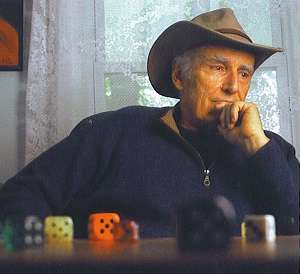

Luke Rhinehart

| Luke Rhinehart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

George Cockcroft November 15, 1932 Albany, New York |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Humor |

| Notable works |

The Dice Man (1971) Adventures of Wim (1986) The Search for the Dice Man (1993) |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Luke Rhinehart (born George Cockcroft November 15, 1932) is the American writer of nine novels, most notably The Dice Man, a 1971 novel about a psychotherapist who casts dice in place of making decisions.

The Dice Man was critically and commercially well received. In 1995, the BBC called it "one of the fifty most influential books of the last half of the twentieth century," and in 1999 Loaded magazine named it "Novel of the Century".[1][2] In 2013, the Telegraph listed it as one of the 50 great cult books of the last hundred years.[3] Although first published in 1971, the book has enjoyed a 21st-century renaissance, being published or republished in more than 60 countries and translated into 26 languages.[4]

His books The Search for the Dice Man, Whim and The Book of the Die continue the comic and philosophical ideas first explored in The Dice Man.

Biography

Rhinehart was born George Cockcroft in Albany, New York, son of an engineer and a civil servant. He received a BA from Cornell University in 1954 and an MA from Columbia University in 1956. In 1964 he received a PhD in American literature, also from Columbia. He married his wife, Ann (who would later become a writer of two romance novels and a volume of poetry) on June 30, 1956. Together they have three children.[5] Rhinehart's brother James Cockcroft is the author of more than 20 books, mostly on Latin American history and society.

After obtaining his PhD, he went into teaching. During his years as a university professor he taught, among other things, courses in Zen and Western literature. He first floated the idea of living by the dice in a lecture: the reaction was equal parts intrigue and disgust, and it was at this point he realized it could become a novel. Rhinehart started experimenting with dice a long time before writing The Dice Man.

In 1971, a London-based startup publisher, Talmy Franklin, discovered the draft of the first third of The Dice Man when he met Luke in Mallorca and a year later published the book.[6] The publisher sold film rights to the book even before publication and with this money and success Luke became a full-time writer.

Since then, he and his family lived for three years on Mallorca (where he finished writing The Dice Man,[7] lived aboard a big trimaran that became the boat of his novel Long Voyage Back, lived for a year (1975) in a sufi commune, and for the last 40 years in a large old farmhouse and former religious retreat[8] in the foothills of the Berkshires in upstate New York. Here he continues to write novels but rarely gives interviews, a "reclusive" stance which has added a sense of mystery to his identity as the "father of dicing".[9]

On 1 August 2012, at the age of 80, Rhinehart arranged for his own death to be announced. It was later revealed as a prank.[10]

Writing

Much of Rhinehart's writing follows the styles of his first book, The Dice Man. He switches rapidly between a first- and third-person view and intersperses that narrative flow with (fictional) excerpts from journals, minutes of meetings, and other sources.[11] This gives the impression of a larger story, of which just a glimpse is seen. In one case, he even quotes from a future book that he did not actually write until more than two decades later. The moods of the book change rapidly too – not mixed together, but standing side by side with only a chapter number, if that, between them. Sections of carefully timed comic relief include a sex scene in a river, various dice parties, and a hallucinogenic tomato plant.[12]

On the other hand, Long Voyage Back, and Matari (retitled White Wind, Black Rider in 2008) show that he is entirely comfortable writing somewhat more traditional fiction,[13] and The Book of est shows that he is capable of writing wholly factual accounts too. In all his books, Rhinehart focuses attention on only a few characters, typically fewer than five. Other characters are introduced, but solely as caricatures or plot devices.

The Book of the Die is a collection of thoughts and ideas about dicing, much in the style that might be expected from Rhinehart's previous work. Interspersed with this are frequent parables, poems, stories. Some are from his earlier books, some from the new ones, some stolen and rewritten from various well-known sayings and writings, some from his followers (both real and imaginary), and some which purport to be from his own life. In each chapter are six dice options with the instructions "Read the options, throw out one or two (or all six) and replace them, then roll a dice and do as suggested." The book contains amusing or absurd sections, as if to counterpoint the occasional more serious sections.[14][15]

Whim tells the story of a Montauk boy, purportedly the savior of his tribe and born of a virgin mother, who is taken from his people to live among "humans" (non-Montauk Americans). Despite being influenced by modern vices such as American Football and marijuana, Whim remains true to his God-given mission to find "ultimate truth". He eventually finds it (in a starvation-driven vision of a potato), and with it the cure for the sickness of the human condition. Whim takes Rhinehart's style to its logical conclusion, the entire book being composed of excerpts from (fictional) books, screenplays and other documents. The book's preface claims that it was written in Deià, Mallorca in 2326. According to the book, an entire industry has grown up publishing books about a Montauk named Whim. In reality, Whim was first published as Adventures of Whim in 1986; as Whim in 2002 and a third iteration in 2015 by Permuted Press.

More recently, Rhinehart completed a sci-fi satire about extra-dimensional creatures resembling furry beach balls who come to Earth to have fun, but end up turning western civilization topsy-turvy.[16]

Screenplays

Though best known as a novelist, Rhinehart has also written nine screenplays. Five are based directly on his novels The Dice Man, The Search for the Dice Man, Whim, Naked Before the World, and White Wind, Black Rider. Two are direct Dice Man sequels featuring the original Luke Rhinehart character: The Dice Lady[17] (co-written with Peter Forbes) and Last Roll of the Die (co-written with Nick Mead). Two other screenplays are Mawson and Picton's Chance are original concepts.

Influence

The ideas in The Dice Man have influenced a number of musicians, writers, artists and commercial ventures.

Music

Luke Rhinehart has appeared in several songs:

|

|

Other music connections:

- "The Dice Man" is an alias used by Richard D. James, the Aphex Twin

- "The Diceman" is the alias used for certain projects of Colin James (Jolly James, Gregg Retch, formerly of Meat Beat Manifesto)

Other art and media

Art that exploits the principle of chance or randomness is called aleatoricism. Several pieces of such art have been partially or wholly inspired by the writings of Luke Rhinehart.

Four seasons of a TV travel series called The Diceman was made between 1998 and 2000 by the Discovery Channel. The destinations and activities of the participants are determined by the roll of a die.[18][19]

There have been at least three documentaries on 'Dice Living' and the philosophy of The Dice Man, including a fifty-minute short film called "Dice World" by Paul Wilmshurst, produced by Channel 4.[20]

In theatre, The Dice House was staged in London's West End. Written by Paul Lucas, the play was inspired by The Dice Man.[21][22]

Journalist Ben Marshall spent two years from 1998 to 2000 experimenting with being a Dice Man and reporting his experiences in Loaded magazine. Loaded subsequently named Luke Rhinehart as novelist of the century.[23][24]

Larnie Reid Fox popularised the idea of the DiceWalk, students of psychogeography having already pioneered the art or science of random or whimsical excursions.[25]

Murder mystery author Terry Mitchell often uses characters who throw dice to make decisions and in his own personal life created the dice road trip, dicing to eat and The Sacred Journey which uses dice in various books to lead to spiritual lie changes.

Commercial ventures

The brewers of Rolling Rock pale lager launched a series of adverts based around the Dice Man theme,[26] and even a 'Dice Life' website, now defunct.

In the 1980s, the UK comic 2000 AD published several Gamebook magazines under the name Dice Man.[27]

Bibliography

- The Dice Man (1971)

- Matari (1975)

- The Book of est (1976)

- Long Voyage Back (1983)

- Adventures of Wim (1986)

- The Search for the Dice Man (1993)

- The Book of the Die (2000)

- Whim (2002 reissue of Adventures of Wim)

- White Wind, Black Rider (2008 reissue of Matari)

- Naked Before the World: A Lovely Pornographic Love Story (2008)

- Jesus Invades George: An Alternative History (2013)

- Invasion (2016)

References

- ↑ http://www.funtrivia.com/en/subtopics/Loaded-Magazine---The-Early-Years-239311.html

- ↑ http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/cr-100345/luke-rhinehart

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/booknews/10432344/50-best-cult-books.html

- ↑ http://permutedpress.com/authors/luke-rhinehart

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/04/three-days-dice-man-never-wrote-money-fame-tanya-gold

- ↑ http://www.lukerhinehart.com/writing-dice-man/

- ↑ http://www.lukerhinehart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/dice-man-deia-chance.pdf

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/media/1999/jun/14/9

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/media/1999/jun/14/9

- ↑ Steve Boggan (2013-01-12). "In search of The Dice Man: An extraordinary journey to track down a cult author - Features - Books". The Independent. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ http://hilobrow.com/2012/11/15/luke-rhinehart/

- ↑ Adventures of Whim (1986)

- ↑ https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/luke-rhinehart/long-voyage-back/

- ↑ The Book of the Die (Harper Collins, 2000)

- ↑ http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-58567-237-0

- ↑ http://www.lukerhinehart.com/the-invasion-of-the-hairy-balls/

- ↑ http://www.lukerhinehart.com/dicelady/

- ↑ "The Diceman (1998–2002)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "The Diceman". The Diceman. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "Diceworld (1999) (TV)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ Rhoda Koenig (2004-02-16). "The Dice House, Arts Theatre London - Reviews - Theatre & Dance". The Independent. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "The Dice House – theatre review | Metro News". Metro.co.uk. 2002-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "Dicing with death | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "The dice man cometh". Telegraph. 2004-02-09. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ Tudor, Silke (2003-05-28). "Life, Cubed | Night Crawler | San Francisco | San Francisco News and Events". SF Weekly. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "Magazine Advert | Rolling Rock Beer | 1990s". The Advertising Archives. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "BARNEY - prog zone". 2000ad.org. 1986-02-01. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

External links

- Official website

- Guardian interview, 27 August 2000

- GQ interview, 7 March 2012

- Independent interview, 12 January 2013