Luang Por Dhammajayo

| Dhammajayo | |

|---|---|

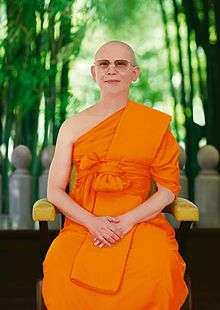

Luang Por Dhammajayo, taken in the old section of Wat Phra Dhammakaya | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Theravada, Maha Nikaya |

| Lineage | Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen |

| Dharma names | Dhammajayo |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Thai |

| Born |

22 April 1944 Sing Buri Province |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | Wat Phra Dhammakaya, Pathum Thani, Thailand |

| Title | Honorary Abbot of Wat Phra Dhammakaya |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro, Chandra Khonnokyoong |

| Website | Biography of Phrathepyanmahamuni |

Dhammajayo (Thai: ธมฺมชโย, rtgs: Thammachayo; born 22 April 1944), also known by the layname Chaiyabun Suddhipol (Thai: ไชยบูลย์ สุทธิผล, rtgs: Chaiyabun Sutthiphon) and his former ecclesiastical title Phrathepyanmahamuni (Thai: พระเทพญาณมหามุนี, rtgs: Phra Thep Yan Mahamuni), is a Thai Buddhist monk.

He was the abbot of the Buddhist temple Wat Phra Dhammakaya, the post he held until 1999 and again from 2006 to December 2011. In December 2016, he was given the post of honorary abbot of the temple.[1][2] He is also the president of the Dhammakaya Foundation. The temple and the foundation are part of the Dhammakaya Movement. He is a student of Maechi Chandra Khonnokyoong and is the most well-known teacher of Dhammakaya meditation.[3]

He has been subject to heavy criticism and some government response.[4] Despite these controversies, he continues to be "probably the most politically, economically, educationally and socially engaged of monks in the modern period" (McDaniel).[5]:110

Early life and background

Luang Por Dhammajayo was born in Sing Buri Province with the lay name Chaiyabun Sutthiphon on 22 April 1944, to Janyong Sutthiphon (his father) and Juri Sutthiphon (his mother).[6]:20 His parents were Lao Song and Thai-Chinese, and separated when he was young. Chaiyabun was raised by his father, who was an engineer working for a government agency.[7][8]:33 Due to a sensitivity for sunlight, Chaiyabun had to wear sunglasses from a young age.[9]

In Wat Phra Dhammakaya's publications, Chaiyabun is described as a courageous child, who would often play dangerous games with fellow friends. It is also described he sometimes had predictive visions.[8]:33 Whilst studying at Suankularb Wittayalai, the owner of the school would bring Chaiyabun regularly to the Sra Prathum Palace, where he would meet with monks. This sparked his interest in Buddhism from a young age. He set up a Buddhist Youth Society together with his fellow students.[6]:24–7[10]:48 Chaiyabun developed a strong interest in reading, especially in books on Buddhist practice and biographies of leading people in the world, both religious and political.[8]:33[11] He came across a book with teachings from Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro and a magazine about the Maechi (nun) Chandra Khonnokyoong.[6]

In 1963, while he enrolled in the Faculty of Economics of Kasetsart University, he started visiting Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen. It was here that he first met Maechi Chandra, student of abbot Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro, who had by then passed away.[12] Maechi Chandra was able to answer Chaiyabun's profound questions, which made him curious to find out more, through the practice of meditation. Under Maechi Chandra's supervision, Chaiyabun attained a deeper understanding of Buddhism.[6]:32–7

Chaiyabun got to know many fellow students both in Kasetsart University and in other universities who were interested in practicing meditation, and encouraged them to join him in learning meditation with Maechi Chandra.[5]:111[11] One of these early acquaintances later became a Buddhist monk and Luang Por Dhammajayos's assistant in the endeavor to establish a meditation center: Phadet Phongsawat, since ordaining known as Luang Por Dattajivo, the vice-abbot of Wat Phra Dhammakaya. At the time when Chaiyabun met Phadet, Phadet was involved in practice of black magic (Thai: ไสยศาสตร์), and would often hold public demonstrations for his fellow students. In Wat Phra Dhammakaya's biographies it is told that every time Chaiyabun joined to watch one of Phadet's demonstrations, the magic would not work. Phadet therefore become curious about Chaiyabun. When Phadet persuaded Chaiyabun to drink alcohol on a student's party, Chaiyabun refused, citing his adherence to the five Buddhist precepts. To test Chaiyabun, Phadet then decided to bring him to his black magic teacher. However, even the teacher could not use his powers in Chaiyabun's presence, which convinced Phadet to learn more about Dhammakaya meditation from Chaiyabun. This was a turning point: from that moment on he has always been Chaiyabun's student and assistant,[8]:33[13]:40–1 and they have a solid friendship.[14]:132

Ordination as monk

During his university years, Chaiyabun wanted to stop his studies to ordain as a monk instead. Maechi Chandra and Chaiyabun's father persuaded him to finish his degree though, arguing that Chaiyabun could do more benefit to society if he was both knowledgeable in mundane matters and spiritual matters. During his university years, he took a vow of lifelong celibacy as a birthday gift for Maechi Chandra. This was an inspiration for many other of Maechi Chandra's students, many of which took vows in the following years.[8]:35 After his graduation from Kasetsart University with a bachelor's degree in economics, he was ordained at Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen on 27 August 1969, and received the monastic name "Dhammajayo", meaning 'The victor through Dhamma'.[15][16] In 1969, a university degree in Thailand was a guarantee someone would get a good position in society, which made Chaiyabun's decision to ordain instead stand out.[15]

Once ordained, he started teaching Dhammakaya meditation together with Maechi Chandra. In the beginning, the meditation courses were carried in a small house called 'Ban Thammaprasit' in the Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen compound. Because of the popularity of both teachers, the number of participants increased and they considered it more appropriate to start a new temple by themselves.[17][8] Although initially they intended to buy a plot of land in Patum Thani, the landowner Khunying Prayat Suntharawet gave a plot four times the requested size to celebrate her birthday. Thus, on 20 February 1970, Maechi Chandra, Phra Dhammajayo, Phra Dattajivo and their students moved to the 196 rai (313,600 m2) plot of land to found a meditation center.[17][18] A book about the initiative was compiled, to inspire people to join in and help.[9]:102–3 They transformed the site into a wooded parkland with a system of canals. The site was later named Wat Phra Dhammakaya.[6]:48

Life as abbot

Meditation teacher

Luang Por Dhammajayo is mostly known for his teachings with regard to Dhammakaya meditation. In his approach of propagating Buddhism he has emphasized a return to a purer Buddhism, as it had been in the past. He has also opposed protective magic and prognostication as signs that Buddhism is deteriorating.[5]:112 LP Dhammajayo is known for his modern style of temple management and iconography.[19] Many followers in the temple believe that his projects are a product of his visions in meditation.[8]:34

In the beginning period, Maechi Chandra still had an important role in fundraising and decision-making. During the years to follow, this would gradually become less, as she grow older and withdrew more to the background of the temple's organization and Luang Por Dhammajayo received a greater role.[8]:41–3 The temple gained great popularity during the 1980s (during the Asian economic boom), especially among the growing well-educated and entrepreneurial middle class, mostly small-business owners and technocrats of Sino-Thai origin. Royalty and high-standing civil servants also started to visit the temple.[20][21]:41, 662[22] In 1995, Wat Phra Dhammakaya caught the nation's attention when a Magha Puja celebration was broadcast live on television, with the then Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn as chairman of the ceremony.[13]:65

Wat Phra Dhammakaya became known for its emphasis on meditation, especially samatha meditation (meditation aiming at tranquility of mind). Every Sunday morning, meditation has been taught to the public.[23][24]:661 Also, special retreats were led by Luang Por Dhammajayo himself in Doi Suthep.[8]:34 One of the core activities of the temple, since its inception, has been the ceremony of 'honoring the Buddhas by food' (Thai: บูชาข้าวพระ), held every first Sunday of the month. This ceremony has been that important, that people from all over the country traveled by bus to join it, from urban and rural areas. It was usually led by Luang Por Dhammajayo himself, and up until her death, by Maechi Chandra Khonnokyoong too. According to the temple's practitioners, in this ceremony food is offered to the Buddhas in meditation. The ceremony has been an important aspect of the temple's attractiveness for the public.[8]:95–7[13]:46, 48, 98–9

Through Luang Por Dhammajayo's teachings, Wat Phra Dhammakaya started to develop a more international approach to its teachings, teaching meditation in non-Buddhist countries as a religiously neutral technique suitable for those of all faiths, or none.[13]:48, 63, 71[25]:242

The miracle controversy and lawsuit

In November 1998, after a ceremony held at the Cetiya of the temple, the temple reported in brochures and national newspapers that a miracle (Thai: อัศจรรย์ตะวันแก้ว) had occurred at the Cetiya, which was witnessed by thousands of people. The miracle involved seeing an image of a Buddha or of Luang Pu Sodh imposed on the sun. Shortly afterwards, the Thai media responded very critical, leading to a nationwide, very intense debate about the state of Thai Buddhism in general, and Wat Phra Dhammakaya in particular, that lasted for an unusually long ten months. Critics believed that Wat Phra Dhammakaya, and Thai Buddhism in general, had become too much of a commercial enterprise (Thai: พุทธพานิช) and had grown corrupt; practitioners and temple devotees argued tradition was being followed.[20][26]:2–3, 13, 124

Media scrutiny worsened when in 1999[27][28] and again in 2002,[29][30] Luang Por Dhammajayo was accused of charges of fraud and embezzlement by the Thai media and later some government agencies when donations of land were found in his name. Wat Phra Dhammakaya denied this, stating that it was the intention of the donors to give the land to the abbot and not the temple.[31][32] Widespread negative media coverage at this time was symptomatic of the temple being made the scapegoat for commercial malpractice in the Thai Buddhist temple community[33][34] in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[35][36]

Under pressure of public outcry and critics, January 1999 the Sangha Supreme Council started an investigation in the accusations, led by Luang Por Ñanavaro, Chief of the Greater Bangkok Region.[37][note 1] The Sangha Council declared that Wat Phra Dhammakaya had not broken any serious offenses against monastic discipline (Vinaya) that were cause for defrocking (removal from monkhood), but four directives were given for the temple to improve itself: setting up an Abhidhamma school, more focus on vipassana meditation, and strict adherence to the rules of the Vinaya and regulations of the Sangha Council.[38] Luang Por Ñanavaro asked the Religious Affairs Department to assist Luang Por Dhammajayo in returning the land to the temple.[39] The abbot stated he was willing to transfer the land, but this required some time, because it required negotiation with the original donors.[40] When by May the temple had not moved all the land yet, a number of things happened.

First of all, a letter was leaked to the press which was signed by the Supreme Patriarch (head of the Thai monastic community). This implied that Luang Por Dhammajayo had to disrobe because he had not transferred donated land back to the temple. A warning had preceded this letter, which government officials said had not yet been forwarded to the Sangha Council and Wat Phra Dhammakaya. The statement had a great impact.[41][42] In response, the Religious Affairs Department pressed criminal charges of embezzlement against the abbot and a close aide.[37][42] In June, the prosecutors started summoning Luang Por Dhammajayo, but he did not go to acknowledge the charges, citing bad health.[43] Moreover, the temple underlined the legal rights of monks under the constitution, pointing out that possessing personal property is common and legal in the Thai Sangha.[44][26]:138 Spokespeople and proponents of the temple's innocence also questioned whether the letter of the Patriarch was not a fake,[26]:143[note 2] and described the response of the ministry and the media as "stirring up controversy" and politically motivated.[46][47] In a statement that was featured in many newspapers, Luang por Dhammajayo declared that he would not disrobe under any circumstances, but "would die in the [monk's] saffron robes".[48]:223 When the Prime Minister himself pressured the abbot to acknowledge the charges, the temple asked for a guarantee that the abbot would not be imprisoned and consequently defrocked.[13]:53[note 3] No such guarantee was given, an arrest warrant followed, and a standoff began between a police force of hundreds, and thousands of the temple's practitioners, in which the latter barricaded the temple's entrances. After two days, Luang Por Dhammajayo agreed to let the police take him when the requested guarantee was given, and a Sangha Council member threatened to defrock the abbot if he did not go with the police.[51][52][53] The abbot was interrogated for three hours, but not defrocked. Then he was released on a bail of two million baht, still on the same day. The news made headlines worldwide. From November onward, Luang Por Dhammajayo started to go to court.[54][55]

Meanwhile, Luang Por Dhammajayo was suspended as abbot, as the trials continued and Luang Por Dhammajayo's deputies continued to manage the temple.[56][26]:139[13]:53–4 Luang Por Dhammajayo had fallen ill and was hospitalized with throat and lung infections.[57][56] The trials proceeded slowly, as the hearings were postponed because of evidence that was not ready, and because of the abbot's illness.[58][59] In an interview held in 1999, LP Dhammajayo said he understood the government's anxiety about Buddhist movements with large gatherings, but still felt perplexed about the controversies.[3]

Campaign against drinking and smoking

In the 2000s, Luang Por Dhammajayo began to focus more on promoting an ethical lifestyle, using the five and eight precepts as a foundation.[60]:424[61] Nationwide people were encouraged to quit drinking and smoking through a campaign called The Lao Phao Buri (Thai: เทเหล้าเผาบุหรี่, literally: 'throw away alcohol and burn cigarettes'), cooperating with other religious traditions. This project led the World Health Organization (WHO) to present a World No Tobacco Day award to Luang por Dhammajayo on 31 May 2004.[62][63][64] The The Lao Phao Buri ceremonies for quitting drinking and smoking later were to become a model of practice in schools and government institutions.[65][66] The temple's campaign was carried to new heights when in 2005 the beverage company Thai Beverage announced to publicly list in the Stock Exchange of Thailand, which would be the biggest listing in Thai history.[67][68] Despite attempts by the National Office of Buddhism (a government agency) to prohibit monks from protesting, two thousand monks of the temple organized a chanting of Buddhist texts in front of the Stock Exchange to pressurize them to decline Thai Beverage's initial public offering.[69][70][note 4] In an unprecedented cooperative effort, the temple was soon followed suit by former Black May revolt leader Chamlong Srimuang and the Santi Asoke movement, holding their protest as well. Subsequently, another 122 religious and social organizations joined, belonging to several religions. The organizations officially asked Prime Minister Thaksin's cooperation to stop the company, in what some of the protest leaders described as "a grave threat to the health and culture" of Thai society.[69][70] While the Stock Exchange pointed out the economical benefits of this first local listing, opponents referred to rising alcohol abuse in Thai society, ranking fifth in alcohol consumption. Ultimately, the protests led to an indefinite postponement of the listing by the Stock Exchange,[71][72] as Thai Beverage chose to list in Singapore instead, and the Stock Exchange chief resigned because of the loss of profit.[73][74]

Charges withdrawn

In 2006, the running lawsuits ended when the Attorney-General withdrew the charges against Luang Por Dhammajayo. He stated that Luang Por Dhammajayo had moved all the land to the name of the temple, that he had corrected his teachings according to the Tipitaka, that continuing the case might create division in society,[note 5] and would not be conducive to public benefit. Furthermore, Luang Por Dhammajayo had assisted the Sangha, the government and the private sector significantly in organizing religious activities. Luang Por Dhammajayo's position as an abbot was subsequently restored.[75][76] Critics questioned whether the charges were withdrawn because of the political influence of Prime Minister Thaksin.[77][78]

New investigations under the 2014 junta

After the coup d'état, the junta started a National Reform Council to bring stability to Thai society, which the junta stated was required before elections could be held.[79] As part of the council, a panel was started to reform Thai religion. This panel was led by Paiboon Nititawan, a former senator who had played a crucial role in the coup. Backed by the bureaucracy, military and Royal Palace, Paiboon sought to deal with any shortcomings in the leading Thai Sangha through legislative means. He was joined by Phra Suwit Dhiradhammo (known under the activist name Phra Buddha Issara), a monk and former infantryman who led the protests that led to the coup as well Mano Laohavanich, a former monk of Wat Phra Dhammakaya, also a member of the reform council.[78][80] In February 2015, Paiboon Nititawan tried to reopen the 1999 case of Luang Por Dhammajayo's alleged embezzlement of land.[78][81] Somdet Chuang and the rest of the Sangha Council were also involved in this, as they were accused of being negligent in not defrocking Luang Por Dhammajayo.[82] The Sangha Council reconsidered the embezzlement and fraud charges, but concluded that Luang Por Dhammajayo had not intended to commit fraud or embezzlement, and had already returned the land concerned.[51][83][note 6] Meanwhile, several Thai intellectuals and news analysts pointed out that Paiboon, Phra Suwit and Mano were abusing the Vinaya (monastic discipline) for political ends, and did not really aim to "purify" Buddhism.[86][79][87]

In a press conference on 29 October 2015, the Department of Special Investigation (DSI), the Thai counterpart of the FBI,[88] stated that its investigators had found that Supachai Srisuppa-aksorn, ex-chairman of the Klongchan Credit Union Cooperative (KCUC), had fraudulently authorised 878 cheques worth 11.37 billion baht to various individuals and organisations, in which a portion totaling more than a billion baht was traced to Wat Phra Dhammakaya, Luang Por Dhammajayo, and the Maharattana Ubasika Chan Khonnokyoong Foundation, among others. Luang Por Dhammajayo admitted to receiving the donations but stated he did not know where the money came from since they were received publicly.[89][90][91][92] In 2015, in a written agreement with the credit union, supporters of the temple had raised 684 million baht linked to Wat Phra Dhammakaya to donate to the KCUC.[93][94] However, apart from the problem of compensation to the credit union, the DSI suspected the temple of having conspired in the embezzlement of Supachai. The charges were laid by an affected client of the credit union, who felt the money the temple had returned had too many strings attached. Moreover, the DSI was pressurized by the reform council.[93][78]

Luang Por Dhammajayo was summoned to acknowledge the charges of ill-gotten gains and conspiring to money-laundering at the offices of the DSI. According to spokespeople, to travel to the DSI would mean a risk for Luang Por Dhammajayo's life due to his deep vein thrombosis.[93][95][96] The temple requested the DSI to let him acknowledge his charges at the temple, a request the DSI refused. As a result, DSI sought an arrest warrant for missing the summons.[97][98] News analysts, lawyers, current and former government officials of the Thai justice system, such as Seripisut Temiyavet,[99][100] came out to state that the DSI was not handling the investigation of the temple with proper legal procedure. It was questioned why the DSI would not let the abbot acknowledge the charges at the temple, which many considered legitimate under criminal law.[101][102][103]

In June 2016, the DSI entered the temple to take Luang Por Dhammajayo in custody. After having searched for a while, a number of laypeople rose and barred the DSI from continuing their search. The DSI, avoiding a confrontation, withdrew.[104] News analysts speculated that Thai law enforcement had not been able to arrest the abbot successfully, because of the complexity of the temple's terrains, the flexibility and amount of practitioners, and the imminent danger of a violent clash.[105][106] Another reason brought up by news analysts was the Thai junta's concern for potential international backlash that may be generated from Wat Phra Dhammakaya's numerous international centers. In fact, international followers had already petitioned the White House and met with US Congressmen regarding the case, citing human rights concerns.[107] Despite the standoff, temple officials stated that they were willing to cooperate with law enforcement, their only request being that the DSI give Luang Por Dhammajayo his charges at the temple due to his health.[108]

To put pressure on the abbot, DSI laid several more charges on the temple. As of February 2017, the Thai junta has laid over three hundred different charges against the temple and the foundation, including alleged forest encroachment and allegedly building the Ubosot illegally in the 1970s.[109][110] While law enforcement was under growing pressure to get the job done, criticism against the operation grew as well, news reporters comparing the temple with Falun Gong in China or the Gulen Movement from Turkey.[111][112][113]

In February 2017, junta leader Prayuth announced a special decree following the controversial Section 44 of the interim constitution, dubbed by critics as the "dictator rule",[112] to give law enforcement a wide range of powers to get Luang Por Dhammajayo into custody.[114][115] The decree included declaring the temple a restricted zone which no-one could access or leave without the authorities' permission, and a 4000-man combined task force of the DSI, police and army to surround and search the temple. The temple showed little resistance and complied with the search.[116][117] Despite having searched every room and building in the temple,[118] the authorities did not withdraw, however, and ordered that the thousands of people who were not temple residents leave the temple.[119][120] Temple spokespeople responded strongly, protesting that the temple had given its full cooperation, and stating that the lay practitioners were there as witnesses to any possible wrongdoing from authorities.[121] Although the temple staff was unarmed, they managed to push through the task force and a deal was brokered to allow lay people to come in the temple.[119][122]

On 10 March 2017, a deal was made allowing authorities to search the temple once again on the condition that representatives of the Human Rights Commission and news reporters were allowed to witness the search.[123] Once again, authorities were not able to find the abbot, resulting in the junta ending the 3 week siege of the temple, however article 44 still remained in effect.[124][125] The cost of the 23-day operation was estimated at about 100 million baht.[126]

The lockdown resulted in a heated debate about article 44. The article was raised as an example of the junta's illegitimacy and unjust means, by the temple and many other critics.[119][127][128] While proponents pointed out that all would be finished if Luang Por Dhammajayo only gave himself over to acknowledge the charges,[129] critics pointed out that Luang Por Dhammajayo would be imprisoned and defrocked if brought into custody.[130][131] Many reporters also questioned the practicality of using Article 44 and using so much resources to arrest one person for questioning in a non-violent crime, and pointed out the viability of trying him in absentia to determine guilt first.[132][133] The junta government stated their intention was not only to look for Luang Por Dhammajayo, but also to replace the temple leadership and "reform" the temple.[134][135]

Following the lock down the junta has pushed for a replacement abbot for the temple, with the junta appointed[136] director of the National Office of Buddhism calling for an outsider to be appointed the temple's abbot. The director stated this was necessary for investigating the temple's assets and defrocking Luang Por Dhammajayo.[137][138][112]

Teachings

Luang Por Dhammajayo's approach to Buddhism seeks to combine both the ascetic and meditative life, as well as modern personal ethics and social prosperity.[14]:131–2 Luang Por Dhammajayo often uses positive terms to describe Nirvana. Apart from the true self, Scott notes that Wat Phra Dhammakaya often describes Nirvana as being the supreme happiness, and argues that this may explain why the practice of Dhammakaya meditation is so popular.[26]:80 In its teachings on how meditation can help improve health and the quality of modern life, the temple can be compared with Goenka.[26]:77 The temple's emphasis on meditation is expressed in several ways. Meditation kits are for sale in stores around the temple, and every gathering that is organized by the temple will feature some time for meditation.[5][25]:242 The temple emphasizes the usefulness of meditating in a group, and public meditations have a powerful effect on the minds of the practitioners.[8]:95–6[139]:389

Luang Por Dhammajayo was heavily influenced by Maechi Chandra Khonnokyoong in his teachings. He turned the Dhammakaya meditation method "into an entire guide of living" (McDaniel), emphasizing cleanliness, orderliness and quiet, as a morality by itself, and as a way to support meditation practice.[21]:662[140][8]:172 In short, the temple's appearance is orderly, and can be described as "a contemporary aesthetic" (Scott), which appeals to practitioners, especially the modern Bangkok middle class.[141][142][26]:56 Practitioners are also encouraged to keep things tidy and clean, through organized cleaning activities. A strong work ethic is promoted through these activities, in which the most menial work is seen as the most valuable and fruitful.[8]:101–3, 171

Wat Phra Dhammakaya has a vision of a future ideal society.[143]:124 The temple emphasizes that the daily application of Buddhism will lead the practitioner and society to prosperity and happiness in this life and the next, and the temple expects a high commitment to that effect.[143]:123 Through meditation, fundraising activities and volunteer work, the temple emphasizes the making of merit,[144]:7[26]:55, 92 and explains how through the law of kamma merit yields its fruits, in this world and the next.[145][8]:167 The ideal of giving as a form of building character is expressed in the temple's culture with the words Cittam me, meaning 'I am victorious', referring to the overcoming of inner defilements (Pali: kilesa).[146][147]

In 2012, the temple broadcast a talk of Luang Por Dhammajayo about what happened to Steve Jobs after his death.[148] The talk came as a response to a software engineer of Apple who had sent a letter with questions to the abbot. Luang Por Dhammajayo described how Steve Jobs looked like in heaven.[149][150] He said that Jobs had been reborn as a deva living close to his former offices, as a result of the karma of having given knowledge to people. He was a deva with a creative, but angry temperament.[151][152] The talk was much criticized, and the abbot was accused of pretending to have attained an advanced meditative state and of attempting to outshine other temples. The temple answered the critics, saying that the talk was meant to illustrate the law of karma, not to defame Jobs, nor to fake an advanced state.[149][150][153]

Recognition

In 1994, LP Dhammajayo received an honorary degree of the Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University.[8]:123–4[14]:131 In 2013, in commemoration of year 2550 of the Buddhist Era, the World Buddhist Sangha Youth (WBSY) presented the Universal Peace Award to LP Dhammajayo at their third WBSY meeting, in recognition of his work in disseminating Buddhism for more than thirty years.[144]:11[154][155] Other awards that have been given to LP Dhammajayo are the Phuttha-khunupakan award from the House of Representatives in recognition for having provided benefit to Buddhism (2009),[156][157] and a World Buddhist Leader Award from the National Office of Buddhism (2014).[158][159]

Phrathepyanmahamuni is the third ecclesiastical title bestowed on him by the Thai Royal Family in recognition of his contribution to the work of Buddhism in Thailand.[13]

The list of the ecclesiastical titles given to him are as follows:[160][161][162]

| Title | Date of Award |

|---|---|

| Phrasudharmayanathera | 1991 |

| Phrarajbhavanavisudh | 1996 |

| Phrathepyanmahamuni | 2011 |

In March 2017, King Rama X approved a request by the junta leader to remove Luang Por Dhammajayo's title for not acknowledging the charges.[163]

Publications

- Luang Por Dhammajayo (2007) Pearls of Inner Wisdom: Reflections on Buddhism, Peace, Life and Meditation (Singapore: Tawandhamma Foundation)] ISBN 978-981-05-8521-1

- Luang Por Dhammajayo (2007) Tomorrow the World Will Change: A Practice for all Humanity (Singapore: Tawandhamma Foundation) ISBN 978-981-05-7757-5

- Luang Por Dhammajayo (2008) Journey to Joy: The Simple Path Towards a Happy Life (Singapore: Tawandhamma Foundation) ISBN 978-981-05-9637-8

- Luang Por Dhammajayo (2008) Lovely Love (Singapore: Tawandhamma Foundation) ISBN 978-981-08-0044-4

- Monica Oien (2009) Buddha Knows: An Interview With Abbot Dhammajayo On Buddhism (Patumthani: Tawandhamma Foundation)

- Luang Por Dhammajayo (2011) At Last You Win (Patumthani: Dhammakaya Foundation) ISBN 978-616-7200-15-6

- Luang Por Dhammajayo (2014) Beyond Wisdom (Patumthani: Dhammakaya Foundation) ISBN 978-616-7200-53-8

See also

Notes

- ↑ Then known by the title "Phraprommolee".

- ↑ The Supreme Patriarch was ill at the time, and could not easily be visited.[45]

- ↑ Disrobing effectively strips a Buddhist monk from his status and position within the monastic community, and is therefore considered by practitioners tantamount to execution.[49][50]

- ↑ The temple used the project name "Thai Buddhist Monks National Coordination Center".[70]

- ↑ In 2006, there were rising political conflicts.[43]

- ↑ The Thai Ombudsman pointed out that the returning of land could not in itself be cause for withdrawing the charges: it would only make the charges less severe. Moreover, although recognizing that he had no jurisdiction with regard to ecclesiastical law, he did point out some clerical evidence that the Sangha Council had not taken the letter of the Supreme Patriarch very serious.[51] In the same period, Narong Nuchuea, a leading journalist on religious affairs, came out to state that the statement of the Supreme Patriarch was fake, because "politics got involved". He said that the then Supreme Patriarch would never leak such a letter to the press. He also pointed out that letter looked suspicious for several reasons, and was never really taken in consideration by the Sangha Council.[84] The Sangha Council itself stated that the Supreme Patriarch's letter was not an unconditional order: it said that Luang Por Dhammajayo should disrobe if (and only if) he did not return the land on his name to the temple.[85]

References

- ↑ ตั้ง 'พระสมบุญ' นั่งรักษาการเจ้าอาวาสธรรมกาย [Phra Somboon to be named acting abbot of Dhammakaya]]. Bangkok Biz News (in Thai). The Nation Group. 9 December 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ↑ เจ้าคณะจ.ปทุมธานี ปลด 'ธัมมชโย' พ้นเจ้าอาวาส วัดพระธรรมกาย [Head of Region Patumthani removes Dhammajayo from abbot Wat Phra Dhammakaya]. Voice TV. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- 1 2 .Liebhold, David; Horn, Robert (28 June 1999). "Trouble in Nirvana". Time. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Seth Mydans, "Where Buddhism’s Eight-Fold Path Can Be Followed With a Six-Figure Salary"New York Times, Dec 20, 2015

- 1 2 3 4 McDaniel, Justin (2006). "Buddhism in Thailand: Negotiating the Modern Age". In Berkwitz, Stephen C. Buddhism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-782-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tawandhamma Foundation (2007) The Sun of Peace (Bangkok: New Witek)

- ↑ Taylor, J. L. (10 February 2009). "Contemporary Urban Buddhist ‘Cults’ and the Socio-Political Order in Thailand". Mankind. 19 (2): 112–25. doi:10.1111/j.1835-9310.1989.tb00100.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Fuengfusakul, Apinya (1998). ศาสนาทัศน์ของชุมชนเมืองสมัยใหม่: ศึกษากรณีวัดพระธรรมกาย [Religious Propensity of Urban Communities: A Case Study of Phra Dhammakaya Temple] (published Ph.D.). Buddhist Studies Center, Chulalongkorn University.

- 1 2 Dhammakaya Foundation (2005). Second to None: The Biography of Khun Yay Maharatana Upasika Chandra Khonnokyoong (PDF). Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation. p. 83.

- ↑ Dhammakaya Foundation (2010). World Peace Lies Within. Bangkok: Mark Standen Publishing.

- 1 2 ความไม่ชอบมาพากล กรณีสั่งพักตำแน่งเจ้าอาวาสวัดพระธรรมกาย [Suspicious: the case of the removal of Wat Phra Dhammakaya's abbot]. Dokbia Thurakit (in Thai). 20 December 1999. p. 8. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ↑ Dhammakaya Foundation (1996). The Life & Times of Luang Phaw Wat Paknam (PDF). Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation. p. 106. ISBN 978-974-89409-4-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mackenzie, Rory (2007). New Buddhist Movements in Thailand: Towards an understanding of Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Santi Asoke. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-96646-5.(pp40–1)

- 1 2 3 Litalien, Manuel (January 2010). Développement social et régime providentiel en thaïlande: La philanthropie religieuse en tant que nouveau capital démocratique [Social development and a providential regime in Thailand: Religious philanthropy as a new form of democratic capital] (PDF) (Ph.D. Thesis, published as a monograph in 2016) (in French). Université du Québec à Montréal.

- 1 2 ธรรมกาย..."เรา คือ ผู้บริสุทธิ์" ผู้ใดเห็นธรรม ผู้นั้นเห็นเราตถาคต

[Dhammakaya: "We are innocent.", "He who sees the Dhamma, sees me, the Tathagata"]. Dokbia Thurakit (in Thai). 15 March 1999. p. 5. Retrieved 12 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Dhammakaya: "We are innocent.", "He who sees the Dhamma, sees me, the Tathagata"]. Dokbia Thurakit (in Thai). 15 March 1999. p. 5. Retrieved 12 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Rajakaruna, J. (28 February 2008). "Maha Dhammakaya Cetiya where millions congregate seeking inner peace". Daily News (Sri Lanka). Lake House.

- 1 2 เส้นทางพระธรรมกาย

[The path of Wat Phra Dhammakaya]. Thai Post. 6 December 1998 – via Matichon E-library.

[The path of Wat Phra Dhammakaya]. Thai Post. 6 December 1998 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Sirikanchana 2010a.

- ↑ Na Songkhla, N. (1994). Thai Buddhism Today: Crisis? in: Buddhism Into the Year 2000. Khlong Luang, Patumthani: Dhammakaya Foundation. pp. 115–6. ISBN 9748920933.

- 1 2 Falk, Monica Lindberg (2007). Making fields of merit: Buddhist female ascetics and gendered orders in Thailand. Copenhagen: NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-7694-019-5.

- 1 2 McDaniel, Justin (2010). "Buddhists in Modern Southeast Asia". Religion Compass. Blackwell Publishing. 4 (11).

- ↑ Bechert 1997, p. 176.

- ↑ Snodgrass, Judith (2003). "Building Thai Modernity: The Maha Dhammakaya Cetiya". Architectural Theory Review. 8 (2). doi:10.1080/13264820309478494.

- ↑ Swearer, Donald K. (1991). "Fundamentalistic Movements in Theravada Buddhism". In Marty, M.E.; Appleby, R.S. Fundamentalisms Observed. The Fundamentalism Project. 1. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

- 1 2 Newell, Catherine Sarah (1 April 2008). Monks, meditation and missing links: continuity, "orthodoxy" and the vijja dhammakaya in Thai Buddhism (Ph.D.). London: Department of the Study of Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Scott, Rachelle M. (2009). Nirvana for Sale? Buddhism, Wealth, and the Dhammakāya Temple in Contemporary Thailand. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-2410-9.

- ↑ "'I Will Never Be Disrobed' says Thai abbot of Dhammakaya Temple", and "Between Faith and Fund-Raising", Asiaweek 17 September 1999

- ↑ David Liebhold (1999) Trouble in Nirvana: Facing charges over his controversial methods, a Thai abbot sparks debate over Buddhism's future Time Asia 28 July 1999 [2]

- ↑ Yasmin Lee Arpon (2002) Scandals Threaten Thai Monks' Future SEAPA 11 July 2002 [3]

- ↑ Controversial monk faces fresh charges The Nation 26 April 2002

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions – Dhammakaya Foundation". Dhammakaya Foundation. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Newell, Catherine Sarah (2008). Monks, meditation and missing links: continuity, "orthodoxy" and the vijja dhammakaya in Thai Buddhism (Ph.D.). University of London: Department of the Study of Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies. p. 139.

- ↑ Wiktorin, Pierre (2005) De Villkorligt Frigivna: Relationen mellan munkar och lekfolk i ett nutida Thailand (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International) p.137 ISSN 1653-6355

- ↑ Julian Gearing (1999) Buddhist Scapegoat?: One Thai abbot is taken to task, but the whole system is to blame Asiaweek 30 December 1999 [4]<

- ↑ Bangkokbiznews 24 June 2001 p.11

- ↑ Matichon 19 July 2003

- 1 2 ย้อนรอยคดีธัมมชโย

[Review of Dhammajayo's lawsuits]. Matichon (in Thai). 23 August 2006. p. 16. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Review of Dhammajayo's lawsuits]. Matichon (in Thai). 23 August 2006. p. 16. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Udomsi, Sawaeng (2000). "รายงานการพิจารณาดำเนินการ กรณีวัดพระธรรมกาย ตามมติมหาเถรสมาคม ครั้งที่ ๓๒/๒๕๔๑" [Report of Evaluation of the Treatment of the Case Wat Phra Dhammakaya-Verdict of the Supreme Sangha Council 32/2541 B.E.]. วิเคราะห์นิคหกรรม ธรรมกาย [Analysis of Disciplinary Transactions of Dhammakaya] (in Thai). Bangkok. pp. 81–5. ISBN 974-7078-11-2.

- ↑ Religious Affairs Department, Ministry of Education (Thailand) (7 March 1999). สรุปความเป็นมาเกี่ยวกับการดำเนินการกรณีธรรมกาย

[Overview of how the Case Dhammakaya was handled]. Matichon (in Thai). p. 2. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Overview of how the Case Dhammakaya was handled]. Matichon (in Thai). p. 2. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ "Dhammachayo for land transfer postponement"

. The Nation. 26 May 1999. p. A6. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

. The Nation. 26 May 1999. p. A6. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ พระสังฆราชองค์ที่ ๒๐ [The 20th Sangharaja]. Thai PBS (in Thai). 18 December 2016. Event occurs at 9:12. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- 1 2 Puengnet, Pakorn (10 December 1999). ลำดับเหตุการณ์สงฆ์จัดการสงฆ์ 1 ปีแค่พักตำแหน่งธัมมชโย

[Timeline of events: Sangha dealing with Sangha, after 1 year only suspension for Dhammajayo]. ฺBangkok Biz News (in Thai). The Nation Group. p. 2. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Timeline of events: Sangha dealing with Sangha, after 1 year only suspension for Dhammajayo]. ฺBangkok Biz News (in Thai). The Nation Group. p. 2. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - 1 2 18 ปีกับคดีพระธัมมชโย จบไหมที่รัฐบาลนี้? [18 years of lawsuits against Phra Dhammajayo: will it end with this government?]. VoiceTV (in Thai). 27 June 2016. Event occurs at 4:12. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ↑ PR Department Team (19 December 1998). เอกสารชี้แจงฉบับที่ 2/2541-พระราชภาวนาวิสุทธิ์กับการถือครองที่ดิน [Announcement 2/2541-Phrarajbhavanavisudh and land ownership]. www.dhammakaya.or.th (in Thai). Patumthani: Dhammakaya Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 March 2005.

- ↑ ชวนเชื่อใจไชยบูลย์ ไม่เบี้ยวคืนที่ ธรรมกายระส่ำขาดเงิน

[Chuan believes Chaiyabul will return land, Dhammakaya is disorganized and lacks money]. Matichon (in Thai). 15 May 1999. p. 19. Retrieved 13 February 2017 – via Matichon E-library.

[Chuan believes Chaiyabul will return land, Dhammakaya is disorganized and lacks money]. Matichon (in Thai). 15 May 1999. p. 19. Retrieved 13 February 2017 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Phraputthasat-mahabandit (14 June 1999). ศึกษากรณีพระพิมลธรรมกับพระธัมมชโยกับวิกฤติวงการสงฆ์ไทย+สังคมไร้สติ

[Phra Phimontham's and Phra Dhammajayo's case studies: crisis in Thai Sangha and the mindlessness of society]. Dokbia Thurakit (in Thai). pp. 3–4. Retrieved 11 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Phra Phimontham's and Phra Dhammajayo's case studies: crisis in Thai Sangha and the mindlessness of society]. Dokbia Thurakit (in Thai). pp. 3–4. Retrieved 11 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ "Controversial monk faces fresh charges". The Nation (Thailand). 26 April 2002. Archived from the original on 13 July 2007.

- ↑ Scott, Rachelle M. (December 2006). "A new Buddhist sect?: The Dhammakāya temple and the politics of religious difference". Religion. 36 (4). doi:10.1016/j.religion.2006.10.001.

- ↑ Mackenzie 2007.

- ↑ Wiriyapanpongsa, Satien (13 December 2016). ล้วงลับจับธัมมชโย? ผ่าน 2 มุมมอง [Will Dhammajayo perish? From 2 perspectives]. PPTV (in Thai). Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 Chinmani, Vorawit (22 July 2015). เคลียร์ "คำวินิจฉัย" ปาราชิก [Clearing up the analysis of an offense leading to disrobing]. Thai PBS (in Thai).

- ↑ "Scandal over a monk's property". Asiaweek. CNN. 1999. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Neilan, Terence (26 August 1999). "Thailand: Monk ends standoff". The New York Times. Reuters. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ ทนายธรรมกายนัดเคลียร์ปิดบัญชี 28 ต.ค.

[Dhammakaya's lawyer makes appointment on 28 October and clears up issue of closing bank account]. Matichon. 23 October 1999. p. 23. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Dhammakaya's lawyer makes appointment on 28 October and clears up issue of closing bank account]. Matichon. 23 October 1999. p. 23. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ ผวาบึมซ้ำ 2 ล่าศิษย์ธรรมกาย ตรึงวัดบวร

. Thai Rath (in Thai). Wacharapol. 19 November 1999. p. 11. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

. Thai Rath (in Thai). Wacharapol. 19 November 1999. p. 11. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - 1 2 "Thai monk to stand down from temple duties". New Straits Times (413/12/99). The Associated Press. 7 October 1999. p. 19. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Gearing, Julian (30 December 1999). "Buddhist Scapegoat?: One Thai abbot is taken to task, but the whole system is to blame". Asiaweek.

- ↑ เลื่อนสั่งคดี ธัมมชโย ยักยอกเงินวัด

[Hearing Dhammajayo embezzlement money temple postponed]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). The Nation Group. 19 June 2003. p. 3. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Hearing Dhammajayo embezzlement money temple postponed]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). The Nation Group. 19 June 2003. p. 3. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ "เลื่อนฟังคำสั่ง ธัมมชโย"

[Hearing verdict Dhammajayo postponed]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). The Nation Group. 26 August 2003. p. 16. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Hearing verdict Dhammajayo postponed]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). The Nation Group. 26 August 2003. p. 16. Retrieved 18 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Zehner, Edwin (1990). "Reform Symbolism of a Thai Middle–Class Sect: The Growth and Appeal of the Thammakai Movement". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press on behalf of Department of History, National University of Singapore. 21 (2). JSTOR 20071200.

- ↑ Scupin, Raymond (2001). "Parallels Between Buddhist and Islamic Movements in Thailand". Prajna Vihara. 2 (1).

- ↑ "WHO–List of World No Tobacco Day awardees–2004". World Health Organization. 17 September 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ Mackenzie 2007, p. 71.

- ↑ Seeger 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ ทหารสกลนครเทเหล้า เผาบุหรี่ งดเหล้าเข้าพรรษา [Sakon Nakhon's soldiers throw away their alcohol and cigarettes at start of Rains Retreat]. Nation TV (in Thai). The Nation Group. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ กิจกรรมเทเหล้าเผาบุหรี่ ปี 2559 [The Lao Phao Buri activities in 2016]. Paliang Padungsit School (in Thai). 2 June 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Hills, Jonathan (5 April 2005). "CSR and the alcohol industry: a case study from Thailand". CSR Asia. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Kazmin, Amy (19 March 2005). "Buddhist monks protest against IPO plan"

. The Financial Times. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

. The Financial Times. Retrieved 29 November 2016. - 1 2 Inbaraj, Sonny (20 March 2005). "Thailand: Beer and Buddhism, a Definite No, Cry Conservatives". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 ขบวนการต้านน้ำเมา ร้อยบุปผาบานพร้อมพรัก ร้อยสำนักประชันเพื่อใคร? [Resistance against alcohol: a hundred flowers bloom fully, and for who do a hundred institutions compete?]. Nation Weekend (in Thai). The Nation Group. 4 March 2005. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Protests 'halt' Thai beer listing". BBC. 23 March 2005. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "5,000 Buddhists protest against listing breweries on Thai exchange". Today Online. Agence France-Presse. 20 July 2005. Retrieved 29 November 2016 – via The Buddhist Channel.

- ↑ Kazmin, Amy (4 January 2006). "Thai Beverage listing moves to Singapore"

. The Financial Times. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

. The Financial Times. Retrieved 29 November 2016. - ↑ "Thai Bourse Chief Quits After Losing I.P.O. to a Rival". Financial Times. 25 May 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2016 – via New York Times.

- ↑ อัยการถอนฟ้องธัมมชโย ยอมคืนเงินยักยอก 950 ล.

[Prosecutor withdraws charges Dhammajayo, Dhammajayo agrees to return embezzled 950 M.]. Naew Na (in Thai). 23 August 2006. p. 1. Retrieved 6 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Prosecutor withdraws charges Dhammajayo, Dhammajayo agrees to return embezzled 950 M.]. Naew Na (in Thai). 23 August 2006. p. 1. Retrieved 6 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ "Thai court spares founder of Dhammakaya". Bangkok Post. 23 August 2006. Retrieved 11 September 2016 – via The Buddhist Channel.

- ↑ อนาคตธรรมกาย อนาคตประชาธิปไตย [The future of Dhammakaya, the future of democracy]. Thai PBS. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Dubus, Arnaud (22 June 2016). "Controverse autour du temple bouddhique Dhammakaya: un bras de fer religieux et politique" [Controversy regarding the Dhammakaya Buddhist temple: A religious and political standoff]. Églises d'Asie (in French). Information Agency for Foreign Missions of Paris.

- 1 2 Panichkul, Intarachai (8 June 2016). วิพากษ์ "ปรากฎการณ์โค่นธรรมกาย" สุรพศ ทวีศักดิ์ [Surapot Tawisak: commenting on the fall of Dhammakaya]. Post Today (in Thai). The Post Publishing. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ Tan Hui Yee (25 February 2016). "Tense times for Thai junta, Buddhist clergy"

. The Straits Times. Singapore Press Holdings. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

. The Straits Times. Singapore Press Holdings. Retrieved 16 November 2016. - ↑ Thamnukasetchai, Piyanuch (28 February 2015). "Thai abbot to be probed over massive donations". The Nation (Thailand). Asia News Network – via Asia One.

- ↑ Dubus, Arnaud (18 January 2016). "La Thaïlande se déchire à propos de la nomination du chef des bouddhistes" [Thailand is torn about the appointment of a Buddhist leader]. Églises d'Asie (in French). Information Agency for Foreign Missions of Paris.

- ↑ "Investigation of Phra Dhammachayo continues". The Nation (Thailand). 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Iamrasmi, Jirachata (23 July 2015). เคลียร์ "คำวินิจฉัย" ปาราชิก [Clearing up the analysis of an offense leading to disrobing]. Thai PBS (in Thai).

- ↑ ฉุนมติมหาเถรสมาคมอุ้มธรรมกาย พุทธะอิสระยกขบวนพรึบวัดปากน้ำ

[Angered about decision SSC protecting Dhammakaya, Buddha Issara suddenly moves procession to Wat Paknam]. Matichon (in Thai). 23 February 2015. p. 12 – via Matichon E-library.

[Angered about decision SSC protecting Dhammakaya, Buddha Issara suddenly moves procession to Wat Paknam]. Matichon (in Thai). 23 February 2015. p. 12 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Phaka, Kham (16 June 2016). ปัญหาธรรมกายสะท้อนข้อจำกัดอำนาจรัฐรวมศูนย์ [Problems with Dhammakaya reflect limitations in the government's centralizing efforts]. Voice TV (in Thai). Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ ยืนอสส.รื้อคดีธัมมชโย

[Submitting to Attorney-General to revive lawsuit Dhammajayo]. Matichon (in Thai). 4 June 2015. p. 12. Retrieved 25 January 2017 – via Matichon E-library.

[Submitting to Attorney-General to revive lawsuit Dhammajayo]. Matichon (in Thai). 4 June 2015. p. 12. Retrieved 25 January 2017 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Wechsler, Maxmilian (10 May 2009). "Law enforcement agency tries to shake off shackles"

. Bangkok Post. The Post Publishing. p. 6 – via Matichon e-library.

. Bangkok Post. The Post Publishing. p. 6 – via Matichon e-library. - ↑ Thamnukasetchai, Piyanuch (30 October 2015). "DSI to charge abbot of Wat Dhammakaya". The Nation. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Dhammachayo likely to be charged". Bangkok Post. The Post Publishing. 29 October 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Thai abbot to be probed over massive donations". Asia One. Singapore Press Holdings. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Press Release". Dhammakaya Foundation. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 พิษเงินบริจาคพันล้าน [Poisonous donations of a billion baht]. Thai PBS (in Thai). 2 May 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016. Lay summary – Dhammakaya Uncovered (21 April 2016).

- ↑ "Thai Buddhist temple to repay $20 mn in donation scandal". Daily Mail. DMG Media. Agence France-Presse. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ "Police raid Thai temple in search of wanted monk". Thai PBS. 16 June 2016 – via Associated Press.

- ↑ Thana, CS; Constant, Max. "Thai police blocked from arresting controversial abbot". Anadolu Agency. Bangkok. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ Yee, Tan Hui (28 May 2016). "Thai abbot defies orders to appear at fraud probe"

. The Straits Times. Singapore Press Holdings. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

. The Straits Times. Singapore Press Holdings. Retrieved 11 November 2016. - ↑ ธัมมชโย (ไม่) ผิด? [Is Dhammajayo at fault?]. Spring News (in Thai). 6 May 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ เสียงเสรี SEREE VOICE (2016-06-24), ฉบับเฉพาะตอน ทุจริต อผศ.และกรณีพระธัมมชโย, retrieved 2016-12-23

- ↑ Dhammakaya Uncovered (2016-07-02), Former Police General Sereepisuth Temiyaves Schools DSI (Seree Voice Interview with English dubs), retrieved 2016-12-23

- ↑ ย้อนหลัง สนง.คดีอาญาเผย DSI จะส่งพระธัมมชโยฟ้องศาลไม่ได้หากคดีไม่มีมูล [Review: Office of Criminal Law states DSI cannot charge Phra Dhammajayo if lawsuit is baseless]. Thai News Network (in Thai). 27 May 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016 – via Bright TV.

Subtitled here

- ↑ Chatmontri, Winyat (23 May 2016). หมายจับ'พระธัมมชโย'กับความชอบธรรมของดีเอสไอ [Arrest warrant of Phra Dhammajayo and DSI's justice]. Prachatai. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ↑ Wiriyaphanphongsa, Satian (30 May 2016). หมายจับบนศรัทธา "พระธัมมชโย" [Arrest warrants and faith: Phra Dhammajayo]. PPTV (Thailand) (in Thai). Bangkok Media and Broadcasting.

- ↑ "Meditating devotees shield scandal-hit abbot from Thai police". Channel News Asia. Mediacorp. Reuters. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- ↑ ถอดผังวัดพระธรรมกาย ย้ายมวลชน เตรียมรับมือการตรวจค้น [Analyzing a map of Wat Phra Dhammakaya: moving people, preparing for searches]. PPTV (in Thai). Bangkok Media and Broadcasting. 14 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Prateepchaikul, Veera (19 December 2016). "Temple drama a tale of ineptness". Bangkok Post. The Post Publishing. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Macan-Markar, Marwaan (25 Jan 2017). "Thai junta in showdown at Buddhist temple gates". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 29 Jan 2017.

- ↑ "Thai temple says not resisting legal process of abbot". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Murdoch, Lindsay (2016-12-27). "Police delay raid on Thailand's largest temple after stand-off with monks". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ "308 criminal cases filed against Dhammakaya Temple". The Nation. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- ↑ Rojanaphruk, Pravit (18 December 2016). "A Look Inside the Besieged Wat Dhammakaya". Khaosod English. Khao Sod. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 Tostevin, Matthew; Satrusayang, Cod; Thempgumpanat, Panarat (24 February 2017). "The power struggle behind Thailand's temple row". Reuters. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Paka, Kham (20 February 2017). พุทธศาสนา: เลือกที่ใช่เลือกที่ชอบไม่ต้องทะเลาะกัน [Buddhism, choose your preference and don't fight about it]. Voice TV (in Thai). Digital TV Network. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Rojanaphruk, Pravit (16 February 2017). "Dhammakaya Says Govt Siege Not "Buddhist Way"". Khao Sod English. Matichon Publishing. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Laohong, King-oua (16 February 2017). "Assault on Dhammakaya temple 'imminent'". Bangkok Post. Post Publishing. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Police enter temple, search for Phra Dhammajayo begins". Bangkok Post. The Post Publishing. 16 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Special investigation department summons top temple monks". Asia One. Singapore Press Holdings. Asia News Network. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Thousands of Thais obstruct search for wanted monk". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- 1 2 3 "Special investigation department summons top temple monks". Asia One. Singapore Press Holdings. Asia News Network. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Satrusayang, Cod (19 February 2017). "Worshippers defy Thai police at Buddhist temple". Reuters. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Wongyala, Pongpat (19 February 2017). "DSI orders non-residents to leave Dhammakaya". Bangkok Post. Post Publishing. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Charuvastra, Teeranai (19 February 2017). "Dhammakaya Supporters Defy Order to Leave; DSI to Withdraw Forces". Khao Sod English. Matichon Publishing. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ PCL., Post Publishing. "Search resumes at Wat Phra Dhammakaya". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ PCL., Post Publishing. "Temple search ends with no signs of Phra Dhammajayo". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ "Thai police end search of temple without finding monk". Reuters. 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ "Sangha ‘can’t disrobe monk’ - The Nation". The Nation. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ "DSI prepares for "full scale" raid after talks break down". The Nation. The Nation Group. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ รุมจวกรัฐบาลทหาร เผด็จการ คสช.เกินเหตุ ม.44 กวาดล้างวัดพระธรรมกาย [Many criticizing junta, NCPO too authoritarian, using Section 44 to eradicate Wat Phra Dhammakaya]. Peace TV (in Thai). 20 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017 – via Freedom Thailand.

- ↑ "Thai PM not to revoke order over controversial temple until ex-abbot surrenders". Xinhua. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017 – via Global Times.

- ↑ Praiwan, Phra Maha (25 February 2017). คณะสงฆ์ยังอยู่ภายใต้อำนาจรัฐ [The Sangha is still under the state's control]. Lok Wannee (in Thai). Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Petchpradap, Jom (24 February 2017). กำจัดธรรมกายทำลายพุทธศาสนา หนทางสร้างอำนาจควบคุมคนไทย [Removing Dhammakaya and destroying Buddhism: the path to gaining power to control Thai people]. Jom Voice (in Thai). Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Corben, Ron. "Thai Authorities Continue Standoff at Buddhist Temple". VOA. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- ↑ PCL., Post Publishing. "Misguided Section 44 use". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- ↑ สุวพันธุ์ ยันค้นธรรมกายไม่มีเส้นตาย จะทำให้ธรรมกายเหมือนวัดปกติทั่วไป [Suwapan confirms to set no deadline for search Dhammakaya, will change Dhammakaya into a normal temple]. The Nation TV (in Thai). The Nation Group. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ 9.00 INDEX มาตรา 44 กับสถานการณ์ธรรมกาย ยกระดับการเมืองเข้าไปสู่การทหาร [Level 9 on the Section 44 Index in the Dhammakaya situation: from politics to military action]. Matichon Online (in Thai). 17 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Thai junta replaces director of Buddhism department with policeman". Reuters India. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Thailand seeks new abbot for scandal-hit Buddhist temple". Reuters. 23 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Head, Jonathan (22 March 2017). "The curious case of a hidden abbot and a besieged temple". BBC. Bangkok. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ Harvey, Peter (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- ↑ Zehner, Edwin (1990). "Reform Symbolism of a Thai Middle–Class Sect: The Growth and Appeal of the Thammakai Movement". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press on behalf of Department of History, National University of Singapore. 21 (2). JSTOR 20071200.

- ↑ Bunbongkarn, Suchit (1 January 2000). "Thailand: Farewell to Old–Style Politics?". Southeast Asian Affairs. ISEAS, Yosuf Ishak Institute: 285–95. JSTOR 27912257.

- ↑ Zehner, Edwin (June 2013). "The church, the monastery and the politician: Perils of entrepreneurial leadership in post-1970s Thailand". Culture and Religion. 14 (2): 192. doi:10.1080/14755610.2012.758646.

- 1 2 Taylor, J. L. (1989), "Contemporary Urban Buddhist "Cults" and the Socio-Political Order in Thailand", Mankind, 19 (2), doi:10.1111/j.1835-9310.1989.tb00100.x

- 1 2 Seeger, Martin (2006). "Die thailändische Wat Phra Thammakai-Bewegung" (PDF). In Mathes, Klaus-Dieter; Freese, Harald. Buddhismus in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German). 9. Asia-Africa Institute, University of Hamburg.

- ↑ Zehner, Edwin (2005). "Dhammakāya Movement". In Jones, Lindsay. Encyclopedia of Religion. 4 (2 ed.). Farmington Hills: Thomson Gale. p. 2325.

- ↑ ธรรมกายดิ้นดูดลูกค้า ตั้งรางวัลเพิ่มสมาชิกกัลยาณมิตร

[Dhammakaya struggles and attracts customers, announces prize for finding more kalyanamitta members]. Matichon. 28 June 1999. Retrieved 1 November 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Dhammakaya struggles and attracts customers, announces prize for finding more kalyanamitta members]. Matichon. 28 June 1999. Retrieved 1 November 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Aphiwan, Phuttha (2 June 2016). สอนธรรมโดยธัมมชโย อวดอุตริ? [Dhammachayo's Dhamma teaching: claiming superior human states?]. Amarin TV (in Thai). Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Crisis in Thai Buddhism". Asia Sentinel. 1 February 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- 1 2 "'Steve Jobs now an angel living in parallel universe'". Sify. New Delhi. Asian News International. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- 1 2 ธรรมกายแจงปมภัยศาสนา [Dhammakaya responds to issues that threaten [Buddhist] religion]. Thai News Agency. 3 June 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ กระฉ่อนโลกออนไลน์ ธรรมกายเผย'สตีฟ จ็อบส์'ตายแล้วไปไหน [Circulating through the online world: Dhammakaya reveals where Steve Jobs went after his death]. Thai Rath (in Thai). Wacharapol. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ Chantarasiri, Ruangyot (27 August 2012). สังคม ความเชื่อ และศรัทธา

[Society, beliefs and faith]. Lok Wannee (in Thai). p. 2. Retrieved 3 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

[Society, beliefs and faith]. Lok Wannee (in Thai). p. 2. Retrieved 3 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library. - ↑ Hookway, James (31 August 2012). "Thai Group Says Steve Jobs Reincarnated as Warrior-Philosopher". Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Taylor, Jim (2008). Buddhism and Postmodern Imaginings in Thailand: The Religiosity of Urban Space. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7546-6247-1. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ↑ Taylor, Jim (2007). "Buddhism, Copying, and the Art of the Imagination in Thailand". Journal of Global Buddhism. 8.

- ↑ Kairung, Traithep (2009). พุทธคุณูปการ โล่เกียรติคุณแด่ผู้ทำคุณต่อพุทธฯ [Phuttha-khunupakan: Honorary awards for those who have provided benefit for Buddhism]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). Nation Group. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ ถวายรางวัลผู้ทำประโยชน์ต่อพระพุทธศาสนา [Offering rewards for those who have been of benefit to Buddhism]. The Nation (in Thai). Vacharaphol Co., Ltd. 22 April 2009. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ 'ธัมมชโย-ติช นัท ฮันห์'รับรางวัล'ผู้นำพุทธโลก' [Dhammajayo and Thich Nhat Hanh receive World Buddhist Leader Awards]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). Nation Group. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ "ธัมมชโย-ติช นัท ฮันห์" รับรางวัล "ผู้นำพุทธโลก" [Dhammajayo and Thich Nath Hanh receive World Buddhist Leader Awards]. Spring News (in Thai). 5 February 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ ประกาศสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง พระราชทานสัญญาบัตรตั้งสมณศักดิ์ [Announcement of Prime Minister's Office Concerning the Offering of Monastic Titles] (PDF). The Royal Gazette. Special Issue Vol.108, Ch. 213. The Secretariat of the Cabinet. 12 June 1991. p. 7.

- ↑ ประกาศสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง พระราชทานสัญญาบัตรตั้งสมณศักดิ์ [Announcement of Prime Minister's Office Concerning the Offering of Monastic Titles] (PDF). The Royal Gazette. Special Issue Vol.113, Ch. 23b. The Secretariat of the Cabinet. 5 December 1996. p. 20.

- ↑ ประกาศสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง พระราชทานสัญญาบัตรตั้งสมณศักดิ์ [Announcement of Prime Minister's Office Concerning the Offering of Monastic Titles] (PDF). The Royal Gazette. Special Issue Vol.129, Ch. 6b. The Secretariat of the Cabinet. 15 February 2011. p. 2.

- ↑ "ประกาศสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง ถอดถอนสมณศักดิ์ ลงวันที่ ๕ มีนาคม ๒๕๖๐" [Announcement of the Office of the Prime Minister on Removal of Ecclesiastical Title dated 5 March 2017] (PDF). Royal Thai Government Gazette (in Thai). 134 (8 B): 1. 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

Biographies

- Tawandhamma Foundation (2007) The Sun of Peace (Bangkok: New Witek) ISBN 978-974-88547-9-3

- John Hoskin and Robert Sheridan (2010) World Peace Lies Within: One Man's Vision (Bangkok: Mark Standen Publishing) ISBN 978-616-7200-040

External links

- Biography of Luang Por Dhammajayo – Dhammakaya Foundation

- Life and Work of Luang Por Dhammajayo

- Beyond Wisdom – Luang Por Dhammajayo