Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister

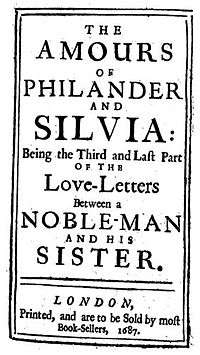

Titlepage of the first edition of the first volume | |

| Author | Anonymous |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Epistolary novel |

| Publisher | Joseph Hindmarsh |

Publication date | 1684, 1685, 1687 |

| Media type | |

Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister is an anonymously published three-volume roman à clef playing with events of the Monmouth Rebellion and exploring the genre of the epistolary novel. It has been attributed to Aphra Behn, but this attribution remains in dispute.[1] [2] The novel is "based loosely on an affair between Ford, Lord Grey of Werke, and his wife's sister, Lady Henrietta Berkeley, a scandal that broke in London in 1682".[3] It was originally published as three separate volumes: Love-Letters Between a Noble-Man and his Sister (1684), Love-Letters from a Noble Man to his Sister: Mixt with the History of Their Adventures. The Second Part by the Same Hand (1685), and The Amours of Philander and Silvia (1687). The copyright holder was Joseph Hindmarsh,[4] later joined by Jacob Tonson.

The novel has been of interest for several reasons. First, some argue that it is the first novel in English.[5] Its connection to Behn means that it has been the subject of a number of books and articles, especially considering Behn's role in the development of the novel and amatory fiction. Secondly, its commentary on the political scandal of the times demonstrate the ways that amatory fiction interprets political appetite and ambition as sexual lasciviousness.[6][7][8]

Plot Summary

- Characters

- Silvia: a beautiful young woman, who slowly becomes more calculating and deceptive as she falls from grace; romantically connected to Philander, Octavio, and Alonzo

- Philander: a young handsome man, who enjoys conquering women; romantically connected to Silvia and Calista

- Octavio: a handsome, rich, and noble man; one of the States of Holland; Calista's brother; in love with Silvia and a rival to Philander

- Cesario: Prince of Condy; leader of the rebellion of the Huguenots in France; aspires to become the next King of France; he is the King's bastard son

- Brilljard: Philander's servant; later Silvia's lawful husband, who promised not to claim her as his wife; however, he falls in love with her

- Calista: Octavio's sister, married to an old Spanish Count; Philander's new conquest

- Sebastian: Octavio's uncle, one of the States of Holland as well

- Sir Mr. Alonzo Jr.: a handsome young gentleman, nephew of the governor of Flanders, by birth a Spaniard; a womanizer

- Osell Hermione: Cesario's mistress, later his wife; neither young nor beautiful

- Fergusano: one of the two wizards appointed to Hermione; Scottish; deals with black magic

Part I

- Dedication

Addressed to Thomas Condon. This dedication is to a relatively unknown young man. The author compares his passionate nature to Philander's, but encourages him to act prudently and judiciously in the art of love.

- Plot

Silvia, a young beautiful woman, is wooed by Philander, her brother-in-law, in an "incestuous" affair.[9] Philander is ultimately successful, and at the end of the novel, he and Silvia flee their country and their families. The plot is the slow decline of honor and nobility, as well as the psychological effects of love.[9] The novel is told through letters between Silvia and Philander that give a deeply personal nature to the affair. Silvia is a loose representation of Henrietta Berkeley, daughter to George Berkeley, 1st Earl of Berkeley who was a prominent Tory politician. She eloped in 1682 with the Whig Ford Grey. Meanwhile, Henrietta's sister and Grey's wife Mary Berkeley was having an affair with James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, Charles II's illegitimate son. As Monmouth would go on later to challenge his uncle James II for the throne when Charles died, the scandal gave the author considerable political fodder to pull from.

Part II

Silvia, disguised as a young man with the name Fillmond, and Philander run away to Holland. Brilljard, who has been married to Silvia to save her from being married to another man by her parents, and two male servants accompany them. On their journey they meet a young Hollander, Octavio. Quickly, a strong friendship develops between Philander and Octavio. Both Brilljard and Octavio develop feelings for Silvia, and when she falls into a violent fever, her true sex is discovered by the servants and the whole truth of their story is revealed to Octavio. Philander leaves the country to avoid being captured by the king, leaving Silvia to recover. Philander's affection lessen in his absence, and both Brilljard and Octavio reveal their love to Silvia. She denies them both.

Angered by Philander's lessening affection, Silvia has Octavio write a letter to Philander in which he confesses his love for her, asking Philander for his permission to do pursue her. Philander, who has also fallen in love with someone else—Calista, wife of the Count of Clarinau—encourages Octavio. Octavio reveals Philander's inconstancy, angered because Calista is his sister. Upset by Philander's betrayal, Silvia attempts suicide but is stopped. After a series of misunderstandings, Silvia enlists Octavio's help in her scheme to get revenge on Philander for successfully wooing Calista. Octavio proposes, and after Silvia learns of Philander's betrayal, she agrees to marry him. The second part ends with Silvia and her maid, Antonett, setting off for a church in a nearby village to meet Octavio.

Part III

- Dedication

To Lord Spencer: The author praises Spencer for his noble birth and the glorious future, that is surely destined for him. The author compares Spencer to Cesario, saying that he is too loyal to be like him, but also warning him against unlawful ambition.

- The Lovers

The main plot of last volume is difficult to ascertain. Many new characters, such as Alonzo, are introduced and the plot contains various love affairs, disguises, mistaken identities, and personal and political intrigues. Despite the title "The Amours of Philander and Silvia" the love between these two characters does not seem to play the major role any more (as it did in part 1). Their feelings towards each other are only dissembled and their relationship to other people gain in importance. Silvia continues to be pursued by Octavio and by Brilljard; Philander pursues Calista and other women. Furthermore, a large part of the action is concerned with Cesario's political scheme to gain the crown. In addition, the narrative form shifts from epistolary to an omniscient narrator's voice, creating distance between the character's motivations and what the reader is allowed to know.

Part two ended with Silvia meeting Philander at a nearby church. Their marriage is prevented by Brilljard, Silvia's lawful husband, who has grown jealous of Octavio. Although Brilljard had promised never to claim her as his wife, he reveals in public that he is already married to her. Silvia and Octavio's reputations are damaged, and although Octavio has learned that she is already married to Brilljard, he still wants to marry her. After Silvia evades the advances of Octavio's uncle Sebastian, she and Octavio flee to Brussels.

Meanwhile, Calista leaves Philander and takes orders after learning he has another mistress. Philander returns to Silvia and quickly woos her again. Octavio and Philander duel over Silvia, and Octavio is badly wounded. Silvia leaves him and absconds with Philander to a nearby town. However, their affections quickly dwindle. Philander starts having other affairs, and Silvia gives birth to a child that is barely mentioned in the text. Its fate is unknown.

Silvia begins leveraging physical affection for loyalty. She enlists Brilljard as her confidant in an attempt to win back Octavio, promising Brilljard sexual favors for his help. Similarly to his sister Calista, Octavio takes orders to avoid unlawful passions. He settles a good pension on Silvia so she can support herself honorably, but she immediately spends it on fine clothes and jewels. In this new guise, she impresses Alonzo at the "Toure," who she had met earlier while inhabiting the guise of a man. With Brilljard's help she manages to deprive him of his fortune.

- The Political Plot

The political plot is focused on Cesario's ambition of becoming King of France. His relationship to Osell Hermione plays a crucial role in this part of the story. She is a former mistress to Cesario and is already past her beauty. To the surprise of everyone, the handsome prince falls in love with her. Only the reader gets to know the reason: Fergusano, a Scottish wizard, made a philtre, that bewitched Cesario and attached him to Hermione. She finally becomes his wife, and stirs up his ambition to become King with the help of two wizards.

Cesario leaves with all his men from Brussels to France, where he proclaims himself King. Cesario's army is defeated by the Royal Army due to his impatience and losing the loyalty of his friends. He is eventually pardoned.

Attribution Questions

Love-Letters was never published under Aphra Behn's name in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries.[10] The primary reason the novels are ascribed to Behn is because of Gerald Langbaine, who in 1691 published Account of the English Dramatick Poets that named Behn as the author.[11] Another reason for the attribution is that the second volume has a title page that read "Printed for A.B." Both prefaces of the second and third volumes are signed "A.B." Other evidence includes: "the fact that Behn was having money difficulties and was having trouble selling her plays by the mid-1680s, as evidenced from her letter borrowing money from [Jacob] Tonson, and that her previous plays and poems indicate that she might have the literary skill to execute Love-Letters." [1]

However, the evidence is only circumstantial. Anonymous publication was very common, and Behn usually did not publish anonymously (The Rover is an exception). Nor can the initials on the book be concretely attributed to "Aphra Behn." Janet Todd explains that, similarly to using anonymous, "A. B. is precisely what anyone might call him or herself when not wanting to be recognized or when insisting on standing for a group or for everyone."[2] In addition, Behn's canon is notoriously hard to pin down, and there are many other works that have been attributed to her incorrectly. [10][12] Despite this, the attribution is commonly given to Behn without scrutiny. Leah Orr concludes that there is no evidence that Behn did not write Love-Letters, but this alone does not mean that we should argue that she did.[1]

Publication History

- First edition (separate volumes)

- 1684, London: Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and his Sister printed by Randal Taylor (trade publisher[13]) but copyright was for J. Hindmarsh.

- 1685, London: Love Letters From a Noble Man to his Sister: Mixt With the History of their Adventures. Either "Printed for A.B." or "Printed for the Author." Copyright is later held by both J. Tonson and J. Hindmarsh.

- 1687, London: The Amours of Philander and Silvia: Being the Third and last Part of the Love-Letters Between a Noble-Man and his Sister. No printer listed. Copyright is later held by both J. Tonson and J. Hindmarsh.

- Later editions (separate volumes)

- 1693, London, Volume 1: J. Hindmarsh and J. Tonson

- 1693, London, Volume 2: J. Hindmarsh and J. Tonson

- 1693, London, Volume 3: J. Hindmarsh and J. Tonson

- Later editions (all three volumes together)

- 1708, London: Daniel Brown, J. Tonson, John Nicholson, Benjamin Tooke, and George Strahan

- 1712, London: D. Brown, J. Tonson, J. Nicholson, B. Tooke, and G. Strahan

- 1718, London: D. Brown, J. Tonson, J. Nicholson, B. Tooke, and G. Strahan

- 1765, London: L. Hawes & Co.

- 1987, London: Virago, 1987, with a new introduction by Maureen Duffy, Virago modern classic, 240

- 1996, London and New York: Penguin, ed. by Janet Todd, Penguin Classics

References

- 1 2 3 Orr, Leah (January 2013). "Attribution Problems in the Fiction of Aphra Behn". The Modern Language Review. 108 (1): 40–51. doi:10.5699/modelangrevi.108.1.0030.

- 1 2 Todd, Janet (1995). ""Pursue that Way of Fooling, and Be Damn'd": Editing Aphra Behn". Studies in the Novel. 27 (3): 304–319. JSTOR 29533072.

- ↑ Pollak, Ellen (2003). Incest & The English Novel, 1684-1814. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0801872049.

- ↑ "Joseph Hindmarsh (Biographical details)". The British Museum. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ Gardiner, Judith Kegan (Autumn 1989). "The First English Novel: Aphra Behn's Love Letters, The Canon, and Women's Tastes". Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature. 8 (2): 201–222. JSTOR 463735. doi:10.2307/463735.

- ↑ Bowers, Toni (2011). Force or Fraud: British Seduction Stories and the Problem of Resistance, 1660-1760. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199592135.

- ↑ Ballaster, Ros (1992). Seductive Forms: Women's Amatory Fiction from 1684 to 1740. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198184775.

- ↑ Steen, Francis F. (2002). "The Politics of Love: Propaganda and Structural Learning in Aphra Behn's Love-Letters between a Nobleman and His Sister". Poetics Today. 23 (2): 91–122. doi:10.1215/03335372-23-1-91.

- 1 2 Steen, Francis F. "Aphra Behn's Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister". University of California at Santa Barbara.

- 1 2 O'Donnell, Mary Ann (2003). Aphra Behn: An Annotated Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Sources (Second ed.). Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0099-2.

- ↑ Langbaine, Gerald (1691). An Account of the English Dramatick Poets. Oxford: L. L. for George West and Henry Clements. p. 23.

- ↑ Greer, Germaine (1996). "Honest Sam. Briscoe". In Myers, Robin; Harris, Michael. A Genius for Letters: Booksellers and Bookselling from the 16th to the 2oth Century. Oak Knoll Press. p. 33–47. ISBN 978-1884718168.

- ↑ Todd, Janet (2000). The Secret Life of Aphra Behn. Bloomsbury Reader. p. 301. ISBN 9781448212545.

External links

- Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister, In Three Parts, the 4th edition (1712) Printed for D. Brown, J. Tonson, J. Nicholson, B. Tooke, and G. Strahan, London

- Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister at Project Gutenberg

- E-text from Pierre Marteau’s Publishing House

Further reading

- Steen, Francis F. (Spring 2002). "The Politics of Love: Propaganda and Structural Learning in Aphra Behn's Love-Letters between a Nobleman and His Sister". Poetics Today. 23 (1): 91–122. doi:10.1215/03335372-23-1-91.