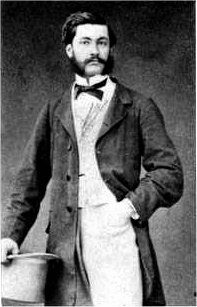

Louis Le Prince

| Louis Le Prince | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince 28 August 1841 Metz, France |

| Disappeared |

16 September 1890 (aged 49) Dijon, France |

| Status | Vanished |

| Occupation | Chemist, engineer, inventor, filmmaker |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Le Prince-Whitley (m. 1869–90) |

Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince (French: [lwi lə pʁɛ̃s]; 28 August 1841 – vanished 16 September 1890) was a French inventor who shot the first moving pictures on paper film using a single lens camera.[1][2] He has been heralded as the "Father of Cinematography" since 1930.[3]

A Frenchman who also worked in the United Kingdom and the United States, Le Prince conducted his ground-breaking work in 1888 in the city of Leeds in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England.[4] In October 1888, Le Prince filmed moving picture sequences Roundhay Garden Scene and a Leeds Bridge street scene using his single-lens camera and Eastman's paper film.[5] These were several years before the work of competing inventors such as William Friese-Greene, Auguste and Louis Lumière, and Thomas Edison.

He was never able to perform a planned public demonstration in the US because he mysteriously vanished from a train on 16 September 1890.[1] His body and luggage were never found, but, over a century later, a police archive was found to contain a photograph of a drowned man who could have been him.[5]

Not long after Le Prince's disappearance, Thomas Edison tried to take credit for the invention. But Le Prince’s widow and son, Adolphe, were keen to advance his cause as the inventor of cinematography. In 1898 Adolphe appeared as a witness for the defence in a court case brought by Edison against the American Mutoscope Company. (The suit claimed that Edison was the first and sole inventor of cinematography, and thus entitled to royalties for the use of the process).

Adolphe Le Prince was not allowed to present his father's two cameras as evidence (and so establish Le Prince’s prior claim as inventor) and eventually the court ruled in favour of Edison. However, a year later that ruling was overturned.[6]

Forgotten inventor of motion pictures

The early history of motion pictures in the United States and Europe is marked by battles over patents of cameras. In 1888 Le Prince was granted an American dual-patent on a 16-lens device that combined a motion picture camera with a projector. A patent for a single-lens type (MkI) was refused in America because of an interfering patent, yet a few years later the same patent was not opposed when the American Thomas Edison applied for one.

On October 14, 1888, Le Prince used an updated version (MkII) of his single-lens camera to film Roundhay Garden Scene. He exhibited his first films in the Whitley factory in Hunslet, Leeds and in Oakwood Grange, the Whitley family home in Roundhay, Leeds, but they were not distributed to the general public.

The following year, he took French-American dual citizenship in order to establish himself with his family in New York City and to follow up his research. However, he was never able to perform his planned public exhibition at Morris–Jumel Mansion in Manhattan, in September 1890, due to his mysterious disappearance. Consequently, Le Prince's contribution to the birth of the cinema has often been overlooked.

Life

| “ | "In conclusion, I would say that Mr. Le Prince was in many ways a very extraordinary man, apart from his inventive genius, which was undoubtedly great. He stood 6ft. 3in. or 4in. (190cm) in his stockings, well built in proportion, and he was most gentle and considerate and, though an inventor, of an extremely placid disposition which nothing appeared to ruffle." Declaration of Frederic Mason (wood-worker and assistant of Le Prince, April 21, 1931, American consulate of Bradford, England) |

” |

Childhood and school

Le Prince was born on Saint-Georges street in Metz, France, on 28 August 1841.[1][7][8] His father was a major of artillery in the French Army[9] and an officer of the Légion d'honneur. He grew up spending time in the studio of his father's friend, the photography pioneer Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre,[9] from whom the young Le Prince received lessons relating to photography and chemistry and for whom he was the subject of a Daguerrotype, an early type of photograph. His education went on to include the study of painting in Paris and post-graduate chemistry at Leipzig University,[9] which provided him with the academic knowledge he was to utilise in the future.

Adulthood

He moved to Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK in 1866, after being invited to join John Whitley,[1] a friend from college, in Whitley Partners of Hunslet,[10] a firm of brass founders making valves and components. In 1869 he married Elizabeth Whitley, John's sister[1] and a talented artist. The couple started a school of applied art, the Leeds Technical School of Art, in 1871, and became well renowned for their work in fixing colour photography on to metal and pottery, leading to them being commissioned for portraits of Queen Victoria and the long-serving Prime Minister William Gladstone produced in this way; these were included alongside other mementos of the time in a time capsule—manufactured by Whitley Partners of Hunslet—which was placed in the foundations of Cleopatra's Needle on the embankment of the River Thames.

In 1881 Le Prince went to the United States[9] as an agent for Whitley Partners, staying in the country along with his family once his contract had ended. He became the manager for a small group of French artists who produced large panoramas, usually of famous battles, that were exhibited in New York City, Washington DC and Chicago.[9][10] During this time he continued the experiments he had begun, relating to the production of 'moving' photographs and to find the best material for film stock.

During his time in the US, Le Prince built a camera that utilised sixteen lenses,[10] which was the first invention he patented. Although the camera was capable of 'capturing' motion, it wasn't a complete success because each lens photographed the subject from a slightly different viewpoint and thus the projected image jumped about.

After his return to Leeds with his family in May 1887,[10] Le Prince built and then patented a single-lens camera. It was first used on 14 October 1888 to shoot what would become known as Roundhay Garden Scene, the world's first motion picture. Le Prince later used it to shoot trams and the horse-drawn and pedestrian traffic crossing Leeds Bridge. The film was shot from Hicks the Ironmongers, now the British Waterways building, a building on the south east side of the bridge,[1] now marked with a commemorative blue plaque. These pictures were soon projected on a screen in Leeds, making it the first motion picture exhibition.

Suspicious disappearance

In September 1890, Le Prince was preparing to go back to the UK to patent his new camera, to be followed by a trip to the US to promote it. Before his journey, he decided to return home and visit friends and family. Having done so, he left Bourges on 13 September to visit his brother in Dijon. He would then take the 16 September train to Paris, but when the train arrived, his friends discovered that Le Prince was not on board.[11] He was never seen again by his family or friends.[1] No luggage or corpse was found in the Dijon-Paris express, nor along the railway. No one saw Le Prince at the Dijon station, except his brother. No one saw Le Prince in the Dijon–Paris express after he was seen boarding it. No one noticed any strange behaviour or aggression in the Dijon-Paris express.[11]

The French police, Scotland Yard and the family undertook exhaustive searches but never found his body or luggage. This mysterious disappearance case was never solved. Four main theories have been proposed:

- Perfect suicide

- The grandson of Le Prince's brother told film historian Georges Potonniée that Le Prince wanted to commit suicide because he was on the verge of bankruptcy. He had already arranged his suicide and he managed for his own body and belongings never to be found. However, Potonniée noted that Le Prince's business was profitable and that he was proud of his inventions, and thus had no reason to commit suicide.[12]

- Patent Wars assassination, "Equity 6928"

- Christopher Rawlence pursues the assassination theory, along with other theories, and discusses the Le Prince family's suspicions of Edison over patents (the Equity 6928) in his 1990 book and documentary The Missing Reel. At the time that he vanished, Le Prince was about to patent his 1889 projector in the UK and then leave Europe for his scheduled New York official exhibition. His widow assumed foul play though no concrete evidence has ever emerged and Rawlence prefers the suicide theory. In 1898, Le Prince's elder son Adolphe, who had assisted his father in many of his experiments, was called as a witness for the American Mutoscope Company in their litigation with Edison [Equity 6928]. By citing Le Prince's achievements, Mutoscope hoped to annul Edison's subsequent claims to have invented the moving-picture camera. Le Prince's widow Lizzie and Adolphe hoped that this would gain recognition for Le Prince's achievement, but when the case went against Mutoscope their hopes were dashed. Two years later Adolphe Le Prince was found dead while out duck shooting on Fire Island near New York.[13]

- Disappearance ordered by the family

- In 1966, Jacques Deslandes proposed a theory in Histoire comparée du cinéma (The Comparative History of Cinema), claiming that Le Prince voluntarily disappeared due to financial reasons (already shown to be false) and "familial conveniences". Journalist Léo Sauvage quotes a note shown to him by Pierre Gras, director of the Dijon municipal library, in 1977, that claimed Le Prince died in Chicago in 1898, having moved there at the family's request because he was homosexual ; but he rejects that assertion.[14] There is no evidence to suggest that Le Prince was gay.[15]

- Fratricide, murder for money

- In 1967, Jean Mitry proposed, in Histoire du cinéma, that Le Prince was killed. Mitry notes that if Le Prince truly wanted to disappear, he could have done so at any time prior to that. Thus, most likely he never even boarded the train in Dijon. He also questions that if the brother, who was confirmed to be the last person to see Le Prince alive, knew Le Prince was suicidal, why didn't he try to stop him, and why didn't he report this to the police before it was too late?[16]

Le Prince was officially declared dead in 1897.[17] A photograph of a drowning victim from 1890 resembling Le Prince was discovered in 2003 during research in the Paris police archives.[9]

Career

Decisive meetings

- Louis Daguerre

- Eadweard Muybridge

- Jean Le Roy

Late recognition

Le Prince is considered by many film historians[18] as the true father of motion pictures.[19]

| “ | "Le Prince had indeed succeeded making pictures move at least seven years before the Lumière brothers and Thomas Edison, and so suggests a re-writing of the history of early cinema." Richard Howells (Screen vol.47 #2, pp. 179–200, Oxford University Press, 2006) |

” |

Even though Le Prince's solo achievement is unchallenged, except for advocates of William Friese-Greene, his work was long forgotten; he disappeared on the eve of the first public demonstration of the result of years of toil in his Leeds workshop and tests conducted at the New York Institute for the Deaf. Despite his pursuit of trademarks over in the United States, the dominance and influence of his rival Thomas Edison, founder of the oligopolistic Edison Trust, became unstoppable.

For the April 1894 commercial exploitation of his personal kinetoscope Parlor, Thomas Edison is credited in the US as the inventor of cinema, while in France, the Lumière Brothers are hailed as inventors of the Cinématographe device and for the first commercial exploitation of motion picture films, in Paris in 1895. Like Le Prince, another untold proto-cinema figure is the French inventor, Léon Bouly, who created the first "Cinématographe" device and patented it in 1892 (Patent N°219,350). He was never credited, as two years later his patent, which he had left unpaid, was bought by the Lumière Brothers (Patent N°245,032).

However, in Leeds, West Yorkshire, in the UK, Le Prince is celebrated as a local hero. On 12 December 1930, the Lord Mayor of Leeds unveiled a bronze memorial tablet at 160 Woodhouse Lane (then Auto Express Engineering Company), Le Prince's workshop. In 2003, the University's Centre for Cinema, Photography and Television was named in his honour. Le Prince's workshop in Woodhouse Lane was until recently the site of the BBC in Leeds, and is now part of the Leeds Beckett University Broadcasting Place complex, where a blue plaque commemorates his work. (coordinates: 53°48′20.58″N 1°32′56.74″W / 53.8057167°N 1.5490944°W). His historic moving pictures are shown in the cinema of the Armley Mills Industrial Museum, Leeds.

In France, an appreciation society was created as L'Association des Amis de Le Prince (Association of Le Prince's Friends) which still exists in Lyon.

In 1990, Christopher Rawlence wrote The Missing Reel, The Untold Story of the Lost inventor of Moving Pictures and produced the TV programme The Missing Reel (1989) for Channel Four, a dramatised feature on the life of Le Prince.

In 1992, the Japanese filmmaker Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell) directed Talking Head, an avant-garde feature film paying tribute to the cinematography history's tragic ending figures such as George Eastman, Georges Méliès and Louis Le Prince who is credited as "the true inventor of eiga", Japanese for "motion picture film".

In 2013, a feature documentary, The First Film, on the life and inventions of Le Prince was made, with new research material and documentation on the life of Le Prince and his patents. Produced and directed by Leeds-born David Nicholas Wilkinson, it was filmed in England, France and the United States by Guerilla Films. (Association des Amis d'Augustin Leprince).

The First Film features many eminent historians to tell the story, including Michael Harvey, Stephen Herbert, Mark Rance, Daniel Martin, Jacques Pfend, Adrian Wootton, Tony North, Mick McCann, Tony Earnshaw, Carol S Ward, Liz Rymer, and twice Oscar nominated DOP Tony Pierce-Roberts. Le Prince's great, great granddaughter Laurie Snyder also makes an appearance.

The First Film, documenting that Le Prince was first, had its world première in June 2015 at the Edinburgh Film Festival and opened in UK cinemas on the 3rd July 2015.

As few in the British press knew the story it had features on News at Ten, The Today Programme, the Daily Express, Times, Telegraph. It featured in America on CBS’ This Morning. Rotten Tomatoes had a rating of 89%. The film also played in film festivals in the US, Canada, Russia, Ireland and Belgium.

On 8 September 2016 it played at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York, where 126 years earlier Le Prince would have screened his films had he not disappeared. The Mansion used to be George Washington’s old headquarters, and was where the first sitting of the American Government took place. Until The First Film screened Le Prince's films had never been shown there before. Thus their inclusion in the documentary was squaring the circle 126 years late. For two week running the New York Times had the film in its recommended events listing. [20]

LePrince Cine Camera-Projector types

Le Prince's legacy

Remaining material and production

Le Prince developed his single-lens type camera in a workshop at 160 Woodhouse Lane, Leeds. An updated version of this model was used to direct his motion-picture films. Remaining surviving production consists of a scene in the garden at Oakwood Grange (his wife's family home, in Roundhay), another at Leeds Bridge and an Accordion Player.

These world's first motion picture films no longer exist, as Le Prince's body and effects disappeared two years later, but parts of the original paper film strips remaining in the camera (Mark II) were found and exploited later.

Half a century later, Le Prince's daughter, Marie, gave the remaining apparatus to the National Science Museum, London (it's now in the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television (NMPFT), Bradford, which opened in 1983 and in 2006 was renamed the National Media Museum). In May 1931, photographic plates were produced by workers of the Science Museum from paper print copies provided by Marie Le Prince.[2] In 1999, the copies were restored, remastered and re-animated to produce a digital version which was uploaded on to the NMPFT website as public resources ("Roundhay" at the Wayback Machine (archived March 16, 2007) and "Leeds"). These versions are running at the modern cinématographe 24 frames per second (frame/s) rate (Roundhay Garden at 24.64 frame/s and Leeds Bridge at 23.50 frame/s), but Le Prince used the frame-rate adjust device built into his apparatus to test various speeds. According to Adolphe Le Prince, who assisted his father at Leeds, Roundhay Garden is believed to have been shot at 12 frame/s and Leeds Bridge at 20 frame/s.[21]

Since the NMPFT release, various names are used to designate the untitled films, such as "Leeds Bridge" or "Roundhay Garden Scene". Actually, all current online versions (e.g., GIF, FLV, SWF, OGG, WMV, etc.) are derived from the NMPFT files, and these tentative titles are not canon to Le Prince whose mother tongue was French. However, "Leeds Bridge" is believed to be the original title, as the traffic sequence was referred to as such by Frederick Mason, one of Le Prince's mechanics.

Man Walking Around a Corner (LPCC Type-16)

Unremastered film, original frames copy (14 frames) by National Science Museum, London circa 1931. (Courtesy NMPFT, Bradford) NMPFT. Filmed in Paris before 18.08.1887.

Unremastered film, original frames copy (14 frames) by National Science Museum, London circa 1931. (Courtesy NMPFT, Bradford) NMPFT. Filmed in Paris before 18.08.1887.

The last remaining production of Le Prince's 16-lens camera is a frame sequence of a man walking around a corner. It is believed to have been shot with the 16-lens type but this is unsure as it appears as though it was made with a single glass plate, not an Eastman American film. Pfend Jacques, a French cinema-historian and Le Prince specialist, confirms that these images where shot in Paris, at the corner of Rue Bochart-de-Saron (where Le Prince was living) and Avenue Trudaine. Le Prince, who was in Leeds at that time, sent the images to his wife in New York City in a letter dated 18 August 1887. It is a part of a gelatine film shot in 32 fps.

An amateur remastering of all 16 frames is here on YouTube. The individual frames used are here on Flickr.

Roundhay Garden Scene (LPCCP Type-1 MkII)

Roundhay, 1888 original frames copy (20 frames) by National Science Museum, London 1931 (Courtesy of NMPFT, Bradford).

Roundhay, 1888 original frames copy (20 frames) by National Science Museum, London 1931 (Courtesy of NMPFT, Bradford).- Roundhay film (52 frames) by NMPFT, Bradford 1999.

The 1931 National Science Museum copy of the remaining film sequence shot in Roundhay garden features 20 frames (run time 1.66 seconds at 12 frame/s). The digital version produced by the NMPFT has 52 frames (run time 2.11 seconds at 24.64 frame/s) and switches the left side and the right side, since the house is actually incorrectly shown on the right-hand side of the scene in the 1931 copy. It is believed to have been mirrored because of paper parts stuck on the left side of the film that would reduce the visibility. The reason is both physiologic and cultural—a Western viewer's eyes are used to automatically watch from top left to right (this reflex action comes from the reading direction taught in childhood). The garden sequence film's damaged side results in distortion and deformation on the inverted, right side of the digital movie. The scene was shot in Le Prince's father-in-law's garden at Oakwood Grange, Roundhay on October 14, 1888.

Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge (LPCCP Type-1 MkII)

Louis Le Prince filmed traffic crossing Leeds Bridge from Hicks the Ironmongers[1] at these coordinates: 53°47′37.70″N 1°32′29.18″W / 53.7938056°N 1.5414389°W.[22]

6-frame sequence (118–124) of Leeds Bridge (National Science Museum, London 1923)

6-frame sequence (118–124) of Leeds Bridge (National Science Museum, London 1923) 20-frame sequence of Leeds Bridge (National Science Museum)(Courtesy NMPFT, Bradford)

20-frame sequence of Leeds Bridge (National Science Museum)(Courtesy NMPFT, Bradford)

The earliest copy belongs to the 1923 NMPFT inventory (frames 118–120 and 122–124), though a larger sequence comes from the 1931 inventory (frames 110–129). Digital footage produced by the NMPFT has 65 frames (run time 2.76 seconds at 23.50 frame/s) although the original Leeds Bridge film of 20 frames was shot by Le Prince's camera at 20 frame/s on a 60 mm film, according to Adolphe Le Prince who assisted his father when this film was shot in late October 1888.

Accordion Player (LPCCP Type-1 MkII)

Unremastered film, 1888 original frames copy (20 frames, 41–59) by National Science Museum, London 1931 (Courtesy of NMPFT, Bradford).

Unremastered film, 1888 original frames copy (20 frames, 41–59) by National Science Museum, London 1931 (Courtesy of NMPFT, Bradford).

The last remaining film of Le Prince's single-lens camera is a sequence of frames of Adolphe Le Prince playing a diatonic button accordion. It was recorded on the steps of the house of Joseph Whitley, Louis's father-in-law.[2] The recording date is probably 1888. The NMPFT has not remastered this film. An amateur remastering of the first 17 frames is here on YouTube.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "BBC Education – Local Heroes Le Prince Biography". Archived from the original on November 28, 1999. Retrieved 1999-11-28. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help), BBC, archived on 1999-11-28 - 1 2 3 Howells, Richard (Summer 2006). "Louis Le Prince: the body of evidence". Screen. Oxford, UK: Oxford Journals. 47 (2): 179–200. doi:10.1093/screen/hjl015. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ THE "FATHER" OF KINEMATOGRAPHY: LEEDS MEMORIAL PIONEER WORK IN ENGLAND Our Special Correspondent. The Manchester Guardian (1901–1959), Manchester, England 13 Dec 1930: 19.

- ↑ "Louis Le Prince, who shot the world's first film in Leeds". BBC. 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Pioneers of Early Cinema: 1, AIMÉ AUGUSTIN LE PRINCE (1841–1890?)" (PDF). www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk. p. 2. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

he developed a single-lens camera which he used to make moving picture sequences at the Whitley family home in Roundhay and of Leeds Bridge in October 1888. ... it has been claimed that a photograph of a drowned man in the Paris police archives is that of Le Prince.

- ↑ "Pioneers of Early Cinema: Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince (1841–1890?)" (PDF). National Media Museum. June 2011. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ The birth certificate mentions "born August on the 28th, 1841 at 5am. The common mistake of making him born in 1842 comes from an article of Ernest Kilburn Scott, mistake made since then in numerous articles, including the one by Simon Popple

- ↑ 1842 is given by these sources: Archived November 28, 1999, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Herbert, Stephen. "Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince". Who's Who of Victorian Cinema. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- 1 2 3 4 Adventures in CyberSound: Le Prince, Louis Aimé Augustin, Dr Russell Naughton (using source: Michael Harvey, NMPFT Pioneers of Early Cinema: 1. Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince)

- 1 2 Irénée Dembowski (1995). "La naissance du cinéma : cent sept ans et un crime...". Alliage, numéro 22, 1995 (in French). Archived from the original on 1999-11-28. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Dembowski (1995): "1928, Georges Potonniée avance une autre hypothèse ... – Augustin Le Prince s'est suicidé. Il était au seuil de la faillite."

- ↑ Burns, Paul. "The History of the Discovery of Cinematography". – "After his disappearance, the Le Prince family led by his wife and son went to court against Edison in what became known as Equity 6928. The famous Patent Wars ensued and by 1908 Thomas Edison was regarded as sole inventor of motion pictures, in the US at least. However, in 1902, two years after Le Prince’s son Adolphe had testified in the suit, he was found shot dead on Fire Island, New York."

- ↑ Léo Sauvage, "Un épisode mystérieux de l'histoire du cinéma : La disparition de Le Prince", Historia, n° 430 bis, sept. 1982, p. 45-51: "une telle affirmation (...) est totalement dépourvue de vraisemblance".

- ↑ Dembowski (1995): "Pierre Gras, conservateur en chef de la Bibliothèque publique de Dijon, en 1977, montra à Léo Sauvage une note (il la cite dans son ouvrage), prise lors de la visite d'un historien connu (il a tu son nom) qui avait déclaré : – Le Prince est mort à Chicago en 1898, disparition volontaire exigée par la famille. Homosexualité. Disons clairement qu'il n'y a pas l'ombre d'une preuve à l'appui d'une telle assertion."

- ↑ Dembowski (1995): "S'il en était ainsi, pourquoi n'a-t-il rien fait pour l'empêcher de réaliser son funeste projet, pourquoi n'a-t-il pas averti la police à temps?"

- ↑ Hannavy, John, ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of nineteenth-century photography. 1. CRC Press. p. 837. ISBN 978-0-415-97235-2.

- ↑ Historians such as Professor Wheeler Winston Dixon, Christopher Rawlence and others

- ↑ Rausch, Andrew (2004). Turning Points In Film History. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-8065-2592-1.

- ↑ Guerilla Films

- ↑ "Cinematography". National Museum of Photography, Film and Television. Archived from the original on 2006-07-11. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ Google Earth Community: First Moving Pictures

Sources

- Insight Collections and Research Centre

- Guinness Book of Movie Facts and Feats

- Who's Who of Victorian Cinema

- The Career of Louis Aimée Augustin Le Prince by E. Kilburn Scott (July 1931)

- "La naissance du cinéma : cent sept ans et un crime..." by Irénée Dembowski (in Kino 1989, translated from Polish to French in Cahiers de l'AFIS, numéro 182, nov.–déc. by Michel Rouzé, quoted by Alliage numéro 22 1995)

- The Missing Reel, by Christopher Rawlence (Athenum Publishers, New York, 1990)

- "Le Prince's Early Film Cameras", by Simon Popple (in Photographica World, September 1993)

- "Le Prince and the Lumières", by Rod Varley (in Making of the Modern World, Science Museum, UK, 1992)

- "Career of Louis Aimée Augustin Le Prince", by E. Kilburn Scott, (in Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, US, July 1931)

- Burns, Paul The History of the Discovery of Cinematography An Illustrated Chronology

- "The Pioneer Work of Le Prince in Kinematography", by E. Kilburn Scott (in The Photographic Journal #63, August 1923, pp. 373–378)

- "Louis Aimée Augustin Le Prince" by Merritt Crawford (in Cinema, 1 December 1930, pp. 28–31)

- L'affaire Lumière. Du mythe à l'histoire, enquête sur les origines du cinéma by Léo Sauvage, 1985 ISBN 2-86244-045-0

- Ingenious Le Prince 16-lens camera

- "Louis Le Prince: the body of evidence" by Richard Howells (in Screen vol.47 #2, Oxford University Press, 2006)

- "Le Prince, inventeur et artiste, précurseur du cinema" by Jean-Jacques Aulas and Jacques Pfend (in Revue d'Histoire du Cinéma N°32, December 2000, p. 9) ISSN 0769-0959

- New research centre honours father of film

- Essential Films, chapter 2, Culture Wars by Ion Martea

- Roundhay Garden Scene (1888), Culture Wars by Ion Martea

- Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge (1888), Culture Wars by Ion Martea

- The Indispensable Murder Book, edited by Joseph Henry Jackson (New York: The Book Society, 1951), pp. 437–464, "The Red and White Girdle" by Christopher Morley. This deals with the murder of Gouffe, and shows the intense study of that trunk murder in 1889–90.

- The facts concerning the life and death of LOUIS AIME AUGUSTIN LEPRINCE, pioneer of the moving pîcture and his family, by Jacques Pfend (Sarreguemines/57200/France) 2014.ISBN 9782954244198.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis Le Prince. |

- Louis Le Prince on IMDb

- THE LEPRINCE DATABASE: jacques.pfend@wanadoo.fr

- L'EMPREINTE DE LOUIS AIME AUGUSTIN LEPRINCE DANS L'HISTOIRE DU CINEMA.(Université Paris Ouest, par Marie Crémaschi. sep. 2013.

- Jean-Jacques Aulas et Jacques Pfend, Louis Aimé Augustin Leprince, inventeur et artiste, précurseur du cinéma

- Adventures In Cybersound – extended biography by Dr Russell Naughton, RMIT University, Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-09-26

- Roundhay Garden Scene on YouTube

- Leeds Bridge on YouTube

- Accordion Player by Louis Le Prince on YouTube a rough video from the first 17 frames

- Louis Le Prince Centre for Cinema, Photography, and Television. University of Leeds. Retrieved 2008-09-26

- The Legend of Louis Le Prince

- Leodis – a photographic archive of Leeds. Leeds Library & Information Service. Allows search for key terms such as Louis Le Prince or Leeds Bridge or Bridge End or Hick Brothers or Auto Express (workshop site), etc.

- National Science Museum, London

- National Media Museum, Bradford

- Armley Mills- Leeds Industrial Museum

- Le Prince single-lens camera 1888, Science & Society Picture Library

- Chronomedia year 1888 (Terramedia)

- Burns, Paul The History of the Discovery of Cinematography 1885–1889 An Illustrated Chronological History

- Local films for local people (BBC Bradford & West Yorkshire)