Lost in Space

| Lost in Space | |

|---|---|

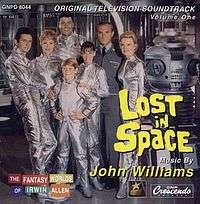

1967 publicity photo showing cast members Angela Cartwright, Mark Goddard, Marta Kristen, Bob May (Robot), Jonathan Harris, June Lockhart, Guy Williams and Billy Mumy | |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Created by | Irwin Allen |

| Directed by |

Irwin Allen |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Dick Tufeld |

| Theme music composer | John Williams |

| Composer(s) |

John Williams Herman Stein Richard LaSalle Leith Stevens Joseph Mullendore Cyril Mockridge Alexander Courage |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of seasons | 3 |

| No. of episodes | 83 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Producer(s) | Irwin Allen |

| Cinematography |

Frank G. Carson Gene Polito Winton Hoch |

| Running time | 51 minutes |

| Production company(s) |

Irwin Allen Productions Van Bernard Productions Jodi Productions 20th Century Fox Television CBS |

| Distributor | 20th Television |

| Release | |

| Original network | CBS |

| Picture format |

black and white (1965–1966) color (1966–1968) |

| Audio format | mono |

| Original release | September 15, 1965 – March 6, 1968 |

| Chronology | |

| Related shows | Lost in Space (film) |

Lost in Space is an American science fiction television series created and produced by Irwin Allen.[1] The series follows the adventures of a pioneering family of space colonists who struggle to survive in a strange and often hostile universe after their ship is sabotaged and thrown off course. The show ran for three seasons, with 83 episodes airing between 1965 and 1968. The first season was filmed in black and white, with the second and third seasons filmed in color.

Although the original concept (depicted in the unaired 1965 pilot episode) centered on the Robinson family, many later storylines focused primarily on Dr. Zachary Smith, played by Jonathan Harris. Smith and the Robot were both absent from the unaired pilot, as the addition of their characters was only decided upon once the series had been commissioned for production.

Originally written as an utterly evil (if careless) saboteur, Smith gradually became the troublesome, self-centered, incompetent character who provided the comic relief for the show and caused much of the conflict and misadventures.[2] In the unaired pilot, what caused the group to become lost in space was a chance encounter with a meteor storm, but in the first aired episode it was Smith's unplanned presence on the ship that sent it off course into the meteor field, and his sabotage which caused the Robot to accelerate the ship into hyperdrive. Smith is thus the key to the story.

Production

In 1962 the first appearance of a space-faring Robinson family occurred in a comic book published by Gold Key Comics. The Space Family Robinson, who were scientists aboard Earth's "Space Station One", are swept away in a cosmic storm in the comic's second issue. These Robinsons were scientist father Craig, scientist mother June, early teens Tim (son) and Tam (daughter), along with pets Clancy (dog) and Yakker (parrot). Space Station One also boasted two spacemobiles for ship-to-planet travel.

The television show launched three years later, in 1965, and during its run CBS and 20th Century Fox reached an agreement with Gold Key Comics that allowed the usage of the name "Robinson" on the TV show; in return, the comic was allowed to append "- Lost In Space" to its title, with the potential for the TV show to propel additional sales of the comic.

The astronaut family of Dr. John Robinson, accompanied by an Air Force/Space Corps pilot and a robot, set out in the year 1997 from an overpopulated Earth in the spaceship Jupiter 2 to travel to a planet circling the star Alpha Centauri with hopes of colonizing it.

The Jupiter 2 mission is sabotaged by Dr. Zachary Smith – an agent for an (unnamed) foreign government – who slips aboard the spaceship and reprograms the robot to destroy the ship and crew. However, when he is trapped aboard, his excess weight alters the craft's flight path and places it directly in the path of a massive meteor storm. Smith manages to save himself by prematurely reviving the crew from suspended animation. The ship survives, but consequent damage caused by Smith's earlier sabotage of the robot leaves them lost in space. In the third episode the Jupiter 2 crashlands on an alien world, later identified by Will as Priplanus, where they spend the rest of the season and survive a host of adventures. Smith, whom Allen had originally intended to write out, remains through all three seasons, as a source of comedic cowardice and villainy, exploiting the eternally forgiving nature of Professor Robinson. Smith was liked by the trusting Will, and tolerated by the women, but he was disliked by both the Robot and the suspicious Major Don West.

At the start of the second season the repaired Jupiter 2 launches into space once more, to escape the destruction of Priplanus following a series of cataclysmic earthquakes, but in the fourth episode the Robinsons crash-land on a strange new world, to become planet-bound again for another season. This replicated the format of the first season, but now the focus of the series was more on humor than on action/adventure, as evidenced by the extreme silliness of Dr. Smith amidst a plethora of unlikely aliens who began appearing on the show, often of a whimsical fantasy-oriented nature. One of these colorful visitors even turned out to be Smith's own cousin, intent on swindling him out of a family inheritance with the assistance of a hostile gambling machine. A new theme tune was recorded by Warren Barker for the second season, but it was decided to retain the original.

In the third season, a major format change was introduced, to bring the series back to its roots as solid adventure, by allowing the Robinsons to travel to more planets. The Jupiter 2 was now allowed to freely travel space, visiting a new world each week, as the family attempt to return to Earth or to reach their original destination in the Alpha Centauri system. A newly built "Space Pod", that mysteriously appeared as though it had always been there, provided a means of transportation between the ship and passing planets, as well as being a plot device to launch various escapades. This season had a dramatically different opening credits sequence and a new theme tune – which, like the original, was composed by John Williams – as part of the show's new direction.

Following the format of Allen's first television series, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, unlikely fantasy-oriented adventure stories were dreamed up that had little to do with either serious science or serious science fiction. The stories had little realism, with, for instance, explosions happening randomly, merely to cover an alien's arrival or departure, or sometimes merely the arrival of some alien artifact.

Props and monsters were regularly recycled from other Irwin Allen shows, as a matter of budgetary convenience, and the same alien would appear on Voyage one week and Lost in Space the next. A sea monster outfit which had featured on Voyage would get a spray paint job for its Lost in Space appearance, while space monster costumes would be reused on Voyage as sea monsters. The clear round plastic pen holder used as a control surface in the episode "The Derelict" turned up regularly throughout the show's entire run.

Spacecraft models, too, were routinely re-used. The foreboding derelict ship from season 1 was redressed to become the Vera Castle in season 3, which, in turn, was reused in several episodes (and flipped upside down for one of them). The Fuel Barge from season 2 became a Space Lighthouse in season 3, with a complete re-use of the effects footage from the earlier story. The derelict ship was used again in season 3, with a simple color change. Likewise the alien pursuer's ship in "The Sky Pirate", which was re-used in the episode "Deadliest of the Species". Moreover, the footage of Hapgood's ship launching into space in episode 6 of season 1 was re-used for virtually every subsequent launch in the following three years, no matter what shape the ship, it supposedly represented, had had on the ground.

Plot

In October 1997, 32 years in the future from the perspective of viewers in 1965, the United States is about to launch one of history's great adventures: man's colonization of deep space. The Jupiter 2 (called Gemini 12 in the unaired pilot episode), a futuristic saucer-shaped spacecraft which owed its design to the Fifties sci-fi movie The Day the Earth Stood Still, stands on its launch pad undergoing final preparations. Its mission is to take a single family on a five-and-a-half-year journey (altered from 98 years in the unaired pilot) to a planet orbiting the nearest star, Alpha Centauri (the pilot show had referred to the planet itself as Alpha Centauri), which space probes have revealed possesses ideal conditions for human life.

The Robinson family, supposedly selected from two million volunteers for this mission, consisted of Professor John Robinson, played by Guy Williams, his wife, Maureen, played by June Lockhart, their children, Judy (Marta Kristen), Penny (Angela Cartwright), and Will (Billy Mumy). They are accompanied by their pilot, U.S. Space Corps Major Donald West (Mark Goddard), who is trained to fly the ship when the time comes for the eventual landing. Initially the Robinsons and Major West will be in freezing tubes for the voyage, with the tubes opening when the spacecraft approached its destination. Unless there is a problem with the ship's navigation or guidance system during the voyage, Major West was only to take the controls during the final approach and landing on the destination planet, while the Robinsons were to strap themselves into contour couches on the lower deck for the landing.

Other nations are racing to colonize space, and they would stop at nothing, not even sabotage, to thwart the United States's effort. It turns out that Dr. Zachary Smith (Jonathan Harris), Alpha Control's doctor, and later supposedly a psychologist and environmental control expert, is moonlighting as a secret agent for one of those competing nations. After disposing of a guard who catches him on board the spacecraft, Smith reprograms the Jupiter 2's B-9 environmental control robot, voiced by Dick Tufeld, to destroy critical systems on the spaceship eight hours after launch. Smith, however, unintentionally becomes trapped aboard at launch and his extra weight throws the Jupiter 2 off course, causing it to encounter a meteor storm. This, plus the robot's rampage which causes the ship to prematurely engage its hyperdrive, causes the expedition to become hopelessly lost in the infinite depths of outer space.

The Robinsons are regularly placed in danger by Smith, whose selfish actions and laziness endanger the family frequently. After the first half of the first season, Smith's role assumes less sinister overtones, although he continues to display many character flaws. In "The Time Merchant" Smith shows he actually does care about the Robinsons, when he travels back in time to the day of the Jupiter 2 launch, with the hope of changing his own fate by not boarding the ship, so allowing the Robinsons to start the mission as originally planned. However, he learns that without his weight altering the ship's course, the Jupiter 2 will be destroyed by an uncharted asteroid. So he sacrifices his chance to stay on his beloved Earth, electing to re-board the ship, thus saving the lives of the family and continuing his role amongst them as the reluctant stowaway.

The fate of the Robinsons, Don West and Dr. Smith is never resolved, as the series unexpected cancellation left the Jupiter 2 and her crew literally on the junk-pile at the end of season three.

Characters

- Dr. John Robinson (Guy Williams): The expedition commander, a pilot, and the father of the Robinson children. He is an astrophysicist who also specializes in applied planetary geology.

- Dr. Maureen Robinson (June Lockhart): John's biochemist wife. Her role in the series is often to prepare meals, tend the garden, and help with light construction while adding a voice of compassion. Her counsel is sometimes the only thing that prevents the Robinsons from leaving Dr. Smith behind after some of his particularly heinous actions, because she finds it unthinkable to condemn any human being to a life of total isolation from his own kind. Her status as a doctor is mentioned only in the first episode and in the second-season episode "The Astral Traveler."

- Major Don West (Mark Goddard): The military pilot of the Jupiter 2. He is Dr. Smith's intemperate and intolerant adversary. His mutual romantic interest with Judy was not developed beyond the first few episodes. In the un-aired pilot, "Doctor Donald West" was a graduate student astrophysicist and expert in interplanetary geology, rather than a military man.

- Judy Robinson (Marta Kristen): The oldest child of the Robinsons. She is about 19 years old at the outset of the series. In the unaired pilot, she is described as having given up a promising career in musical theater to go with her family instead.

- Penny Robinson (Angela Cartwright): The middle child. A 13-year-old in the first season, she loves animals and classical music. Early in the series, she acquires a chimpanzee-like alien pet with pointy ears that made one sound, "Bloop". While it is usually referred to by Will and Professor Robinson as the bloop,[3] Penny named the creature "Debbie". Most of Penny's adventures have a fairy-tale quality, underscoring her innocence. She is described in the unaired pilot, "No Place To Hide", as having an IQ of 147 and an interest in zoology.

- Will Robinson (Billy Mumy): The youngest child. A precocious 9-year-old in the first season, he is a child prodigy in electronics and computer technology. Often, he is a friend to Smith when no one else is. Will is also the member of the family closest to the Robot.

- Dr. Zachary Smith (Jonathan Harris): Acting as Alpha Control's flight surgeon in the first episode, he is later referred to as a Doctor of Intergalactic Environmental Psychology,[4] expert in cybernetics, and an enemy agent (roles that are rarely mentioned after the initial episodes). His attempt to sabotage the mission strands him aboard the Jupiter 2 and results in it becoming lost.

- The Robot: The Robot is a Class M-3, Model B9, General Utility Non-Theorizing Environmental Robot, which had no given name. Although a machine, endowed with superhuman strength and futuristic weaponry, he often displayed human characteristics, such as laughter, sadness, and mockery, as well as singing and playing a guitar. The Robot was performed by Bob May in a prop costume built by Bob Stewart. The voice was dubbed by Dick Tufeld, who was also the series' narrator. The Robot was designed by Robert Kinoshita, who was also the designer of the iconic Robby the Robot for the 1956 sci-fi movie Forbidden Planet.[5] Robby appears in LIS #20 "War of the Robots", and the first episode of season three; "Condemned of Space".

Development

By the end of the first season, the character of Smith is permanently established as a bungling, self-serving, greedy and manipulative coward. These character traits are magnified in subsequent seasons. His haughty bearing, and ever-present alliterative repartee, were staples of the character. While he and Major West repeatedly clashed over his goldbricking, or because of some villainy he had perpetrated, the Robot was usually the preferred victim of his barbed and acerbic wit.

Despite Harris being credited as a "Special Guest Star" on every episode, Smith became the pivotal character of the series.[6] Harris was the last actor cast, with the others all having appeared in the unaired pilot. He was informed that he would "have to be in last position" in the credits. Harris voiced discomfort at this, and (with his continuation beyond the first few episodes still in doubt) suggested appearing in the last position as "Special Guest Star." After having "screamed and howled", Allen agreed.[7] The show's writers expected that Smith would indeed be a temporary villain, who would only appear in the early episodes. Harris, on the other hand, hoped to stay longer on the show, but he found his character as written very boring, and feared it would quickly bore the audience too. Harris "began rewriting his lines and redefining his character", by playing Smith in an attention-getting, flamboyant style, and ad-libbing his scenes with colorful, pompous dialogue. Allen quickly noticed this, and liked it. As Harris himself recalled, Allen said, "I know what you're doing. Do more of it!" Mumy recalls how, after he had learned his own lines, Harris would ask to rehearse with him using his own dialogue. "He truly, truly single-handledly created the character of Dr. Zachary Smith that we know," said Mumy. "This man we love-to-hate, a sniveling coward who would cower behind the little boy, 'Oh, the pain! Save me, William!' That's all him!" [6][7]

Episodes

Technology and equipment

Transportation

The crew had a variety of methods of transportation.

Their primary vehicle for space travel was the two-deck, nuclear powered Jupiter 2 flying saucer spacecraft (in the unaired pilot episode, the ship was named the Gemini 12 and consisted of a single deck). On the lower level were the atomic motors (which use "deutronium" for fuel), the living quarters (featuring Murphy beds), galley, laboratory, and the robot's compartment. On the upper level were the guidance control system and suspended animation "freezing tubes" necessary for non-relativistic interstellar travel. The two levels were connected by both an electric elevator and a fixed ladder. The Jupiter 2 explicitly had artificial gravity. Entrances / exits to the ship were via the main airlock on the upper level, or via the landing struts from the lower deck, and, according to one season 2 episode, a back door. The spacecraft was also intended to serve as home to the Robinsons once it had landed on the destination planet orbiting Alpha Centauri. In one third season tale the power core of the Jupiter 2 is shown as absolutely enormous; however, this may have been due to the plot of the episode, involving the travellers' fears being amplified to supply nourishment for an alien fear-vampire, causing the crew to lose touch with reality.

Shown only in episode 3 of season 1, "Para-jet" thrusters, a pair of units worn on the forearms, allowed a user to descend to a planet from the orbiting spaceship and, perhaps, back again to the ship.

The "Chariot" was an all-terrain, amphibious tracked vehicle which the crew used for ground transport when they were on a planet. As stated in episode 3 of season 1, the chariot existed in a dis-assembled state during flight, to be re-assembled once on the ground. The Chariot was actually an operational cannibalized version of the Thiokol Snowcat Spryte,[8] with a Ford 170-cubic-inch (3 L) inline-6, 101 horsepower engine with a 4-speed automatic transmission including reverse. Test footage filmed of the Chariot for the first season of the series can be seen on YouTube.[9]

Most of the Chariot's body panels were clear - including the roof and its dome-shaped "gun hatch". Both a roof rack for luggage and roof mounted "solar batteries" were accessible by exterior fixed ladders on either side of the vehicle. It had dual headlights and dual auxiliary area lights beneath the front and rear bumpers. The roof also had swivel-mounted, interior controllable spotlights located near each front corner, with a small parabolic antenna mounted between them. The Chariot had six bucket seats (three rows of two seats) for passengers. The interior featured retractable metallised fabric curtains for privacy, a seismograph, a scanner with infrared capability, a radio transceiver, a public address system, and a rifle rack that held four laser rifles vertically near the inside of the left rear corner body panel ("Island in the Sky").

The then new and exciting invention called a jet pack (specifically, a Bell Rocket Belt) was used occasionally by Prof Robinson or Major West.

Finally, the "Space Pod" was a small mini-spacecraft first shown in the third and final season, modeled on the Apollo Lunar Module . The Pod was used to travel from its bay in the Jupiter 2 to destinations either on a nearby planet or in space, and the pod apparently had artificial gravity and an auto-return mechanism.

Other technology

For self-defense, the crew of the Jupiter 2 — including Will on occasion — had an arsenal of laser guns at their disposal, both slings-carried rifles and holstered pistols. (The first season's personal issue laser gun was a film prop modified from a toy semi-automatic pistol made by Remco.[10]) The crew also employed a force field around the Jupiter 2 for protection while on alien planets. The force shield generator was able to protect the campsite but in one season 3 episode was able to shield the entire planet.

For communication, the crew used small transceivers to communicate with each other, the Chariot, and the ship. In "The Raft," Will improvised several miniature rockoons in an attempt to send an interstellar "message in a bottle" distress signal. In season 2 a set of relay stations was built to further extend communications while planet-bound.

Their environmental control Robot B-9 ran air and soil tests, was extremely strong, able to discharge strong electrostatic charges from his claws, could detect threats with his scanner and could produce a defensive smoke screen. The Robot could detect faint smells (in "One of Our Dogs is Missing") and could both understand speech as well as speak. In episode 8 ("Invaders From The Fifth Dimension"), the Robot claims the ability to read human minds by translating emitted thought waves back into words.

The Jupiter 2 had some unexplained advanced technology that simplified or did away with mundane tasks. The "auto-matic laundry" took seconds to clean, iron, fold, and package clothes in clear plastic bags. Similarly, the "dishwasher" would clean, wash, and dry dishes in just seconds.

Some technology reflected recent real-world developments. Silver reflective space blankets, a then new invention developed by NASA in 1964, were used in "The Hungry Sea" (air date: October 13, 1965) and "Attack of the Monster Plants" (air date: December 15, 1965). The crew's spacesuits were made with aluminum-coated fabric, like NASA's Mercury spacesuits, and had Velcro fasteners, which NASA first used during the Apollo program (1961-1972).[11]

While the crew normally grew a hydroponic garden on a planet as an intermediate step before cultivating the soil of a planet, they also had "protein pills" (a complete nutritional substitute for whole foods) in cases of emergency ("The Hungry Sea" (air date: October 13, 1965) and "The Space Trader" (air date: March 9, 1966)).

Series history

In 1965 Allen filmed a 50-minute black-and-white series pilot for Fox, which is usually known as "No Place to Hide" (although this title does not actually appear). After CBS accepted the series, the characters Smith and the Robot were added, the spaceship, originally named the Gemini 12, was redesigned by adding a second deck, interior equipment, and altering some consoles slightly, and was rechristened the Jupiter 2. For budget considerations, a good part of the footage included in the pilot episode was reused, being carefully worked into the early series episodes. CBS was also offered Star Trek at around the same time, but turned it down in favor of Lost in Space. In an ironic twist of fate, In 2006, CBS gained the television rights to the Star Trek franchise.

The Lost in Space television series was originally named Space Family Robinson. Allen was apparently unaware of the Gold Key comic of the same name and similar theme. Both were space versions of the novel Swiss Family Robinson with the title changed accordingly. Gold Key Comics did not sue Allen's production company or 20th Century Fox for copyright infringement, as Allen was expected to license the rights for comic book adaptations of his TV properties (as he already had with Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea), but instead changed the title of the comic to Lost in Space to take advantage of the series' prominence.

The first season emphasized adventure and chronicled the daily adventures that a pioneer family might experience if marooned on an alien world. The first half of season 1 included dealing with the planet's unusual orbit, resulting in extremes of cold and heat, and the Robinson party trekking around the rocky terrain and stormy inland oceans of Priplanus in the Chariot to avoid those extremes, encountering dangerous native plants and animals, and a few reasonably plausible off-world visitors. However, midway through the first season, following the two-parter "The Keeper", the format changed to a "Monster of the week" style, and the stories slipped, almost un-noticeably, from straight adventure to stories based on fantasy and fairy tales, with Will even awakening a sleeping princess with a kiss in a second season entry. Excepting special effect shots (which were reused in later seasons), the first season was filmed in black and white, while the second and third seasons were filmed in color.

Beginning in January 1966, ABC scheduled Batman in the same timeslot. To compete, Lost in Space Season 2 allegedly imitated Batman's campy style humor in order to compete against that show's enormous success. Bright outfits, over-the-top action, outrageous villains (Space Cowboys, Pirates, Knights, Vikings, Wooden Dragons, Amazon Feministas and even Bespectacled Beagles) came to the fore, in outlandish stories. The Robinsons were cloned by a colorful critter in an interestingly plodding story, and even attacked by a civilization of "Little Mechanical Men" resembling their Robot who wanted him for their leader in another tale.[6] To make matters worse, stories giving all characters focus were sacrificed, in favor of a growing emphasis on Smith, Will, and the Robot - and Smith's change in character was not appreciated by the other actors. According to Billy Mumy, Mark Goddard and Guy Williams both disliked the shift away from serious science fiction.[12]

The third season had more straight adventure, with the Jupiter 2 now functional and hopping from planet to planet, but the episodes still tended to be whimsical and to emphasize humor, including fanciful space hippies, more pirates, off-beat inter-galactic zoos, ice princesses and Lost in Space's beauty pageant.

One of the last episodes, "The Great Vegetable Rebellion" with actor Stanley Adams as Tybo, the talking carrot, took the show into pure fantasy. (Called "the most insipid and bizarre episode in television history", Kristen recalls that Goddard complained that "seven years of Stanislavski" method acting had culminated in his talking to a carrot.) A writer Irwin had employed to script a planned crossover between Lost in Space and Land of the Giants noted that Irwin seemed scared of the vegetable story, for it got pushed further and further to the back of the schedule, as the filming of season 3 progressed. The episode's writer, Peter Packer, who was one of the most prolific writers for Lost in Space and had penned some of the series best episodes, apologized to Harris for the script, stating he hadn't "one more damned idea in my head". During filming, Guy Williams and June Lockhart were written out of the next two episodes, on full pay, for laughing so much during the production. Astute viewers will notice the smirks as the actors, notably Mark Goddard, tried to contain themselves during the filming of the story. The Great Vegetable Rebellion appears to have directly inspired the "Rulers of Luton" episode on Space 1999 season 2. In 1977 TV Guide listed "The Great Vegetable Rebellion" at position #76 in its list of the '100 Best Episodes of All Time'.

During the first two seasons, episodes concluded in a "live action freeze" anticipating the following week, with the cliff-hanger caption, "To be continued next week! Same time — same channel!" For the third season, the episode would conclude, immediately followed with a vocal "teaser" from the Robot (Dick Tufeld), warning viewers to "Stay tuned for scenes from next week's exciting adventure!" which would highlight the next episode, followed by the closing credits.

There was little ongoing plot continuity between episodes, except in larger goals: for example, to get enough fuel to leave the planet. However, there were some arcs in the show that allowed a small amount of continuity... occasionally. The first half of the first season had an overall arc, as the Robinsons slowly got used to Smith, and as the robot began his journey to being a thinking and self-aware character.

There were four sets of arc stories:

- The initial 5 episode "Mini-series".

- "The Keeper" 2 parter.

- The "Blast off into Space" / "Wild adventure" duo.

- The "Ghost Planet" / "Forbidden World" duo.

Additionally, there were two arcs of linked stories:

- "My Friend Mr Nobody", "Invaders from the 5th Dimension" and "The Oasis" are all directly linked together in narrative flow.

- "Attack of the Monster Plants" and "Return From Outer Space" are linked through Smith's comments in the latter about Prof Robinson taking revenge on him for his actions in the former.

There were also sequels to some episodes ("Return from Outer Space" follows from events in "The Sky is Falling"), and some recurring characters including Space Pirate Tucker, the android Verda, the Green Dimension girl Athena, and Farnum B (each of whom appears in two episodes), and Zumdish (who appears in three episodes).

In an odd moment of referential continuity "Two Weeks in Space" re-used the "Space Music" angle first shown in "Kidnapped in Space", while the "Celestial Department Store Ordering Machine" appeared in two episodes.

After cancellation, the show was successful in reruns and in syndication for many years, appearing on the USA Network in the mid-to-late 1980s, most recently on FX, Sci-Fi Channel, and ALN. It is currently available on Hulu streaming video, and is seen Saturday nights on MeTV.

There are fan clubs in honor of the series and cast all around the world, and many Facebook group pages connecting fans of the show to each other and to the show's stars.

Ratings, awards and popularity

Although it retains a following, the science-fiction community often points to Lost in Space as an example of early television's perceived poor record at producing science-fiction.[13] The series' deliberate fantasy elements, a trademark of Irwin Allen productions, were perhaps overlooked as it drew comparisons to its supposed rival, Star Trek. However, Lost in Space was a mild ratings success, unlike Star Trek, which received very poor ratings during its original network television run. The more cerebral Star Trek never averaged higher than 52nd in the ratings during its three seasons,[14][15] while Lost in Space finished season one with a rating of 32nd, season two in 35th place, and the third and final season in 33rd place.

Lost in Space also ranked third as one of the top five favorite new shows for the 1965-1966 season in a viewer TVQ poll (the others were The Big Valley, Get Smart, I Dream of Jeannie and F Troop). Lost in Space was the favorite show of John F. Kennedy, Jr. while growing up in the 1960s.[16]

Star Trek creator Gene Roddenbery insisted that the two shows could not be compared. He was more of a philosopher, while understanding that Irwin Allen was a storyteller. When asked about Lost in Space, Roddenberry acknowledged: "That show accomplishes what it sets out to do. Star Trek is not the same thing."

While Lost in Space was still reasonably successful, the show was unexpectedly cancelled in 1968 after 83 episodes. The cast members were informed, somewhat rudely, by a brief item in Variety magazine. Such abrupt cancellations would be a habit of CBS, with the same sudden endings for Gilligan's Island and The Incredible Hulk.

The final prime-time episode to be broadcast over CBS was a cast and crew favorite, a repeat from the second season, "A Visit to Hades", on September 11, 1968.

Lost in Space received a 1966 Emmy Award nomination for "Cinematography-Special photographic effects" but did not win, and again in 1968 for "Achievement in visual arts & makeup" but did not win. In 2005, it was nominated for a Saturn Award "Best DVD Retro Television Release", but did not win. In 2008 TVLand nominated and awarded the series for "Awesomest Robot."

Catchphrases

Lost in Space is remembered, in part, for the Robot's oft-repeated lines such as "Warning! Warning!" and "That does not compute". Smith's frequent put-downs of the Robot were also popular, and Jonathan Harris was proud to talk about how he used to lie in bed at night dreaming them up for use on the show. "You Bubble-headed Booby!", "Cackling Cacophony", "Tin Plated Traitor", "Blithering Blatherskyte", and "Traitorous Transistorized Toad" are but a few alongside his trademark lines: "Oh, the pain... the pain!" and "Never fear, Smith is here!" One of Jonathan Harris's last roles was providing the voice of the illusionist praying mantis "Manny" in Disney's A Bug's Life, where Harris used "Oh, the pain... the pain!" near the end of the film.

The catchphrase "Danger, Will Robinson!" originates with the series, but was only ever used once in it, during episode 11 of season 3 ("The Deadliest of the Species"), when the Robot warns young Will Robinson about an impending threat. It was also used as the slogan of the 1998 movie, whose official website had the address www.dangerwillrobinson.com.[17]

Cancellation

In early 1968, while the final third-season episode "Junkyard in Space" was in production, the cast and crew were informally made to believe the series would return for a fourth season. Allen had ordered new scripts for the coming season. A few weeks later, however, CBS announced a list of television series they were renewing for the 1968-69 season, and Lost in Space was not included. Although CBS programming executives failed to offer any reasons why Lost in Space was cancelled, there are at least five suggested reasons offered by series executives, critics and fans, any one of which could be considered sufficient justification for cancellation given the state of the broadcast network television industry at the time. As there was no official final episode, the exploring pioneers never made it to Alpha Centauri nor found their way back to Earth.

The show had sufficient ratings to support a fourth season, but it was expensive. The budget per episode for Season One was $130,980, and for Season Three, $164,788. In that time, the actors' salaries increased; in the case of Harris, Kristen and Cartwright, their salaries nearly doubled. Part of the cost problems may have been the actors themselves: director Richardson saying of Williams' demanding closeups of himself:

- "This costs a fortune in time, it's a lot of lighting and a lot of trouble and Irwin succumbed to it. It got to be that bad."[18]

The interior of the Jupiter 2 was the most expensive set for a television show at the time, about $350,000.[19] (More than the set of the USS Enterprise a couple of years later.)

According to Mumy and other sources, the show was initially picked up for a fourth season, but with a cut budget. Reportedly, 20th Century Fox was still recovering from the legendary budget overruns of Cleopatra, and thus slashed budgets across the board in its film and television productions.[20] Allen claimed the series could not continue with a reduced budget. During a negotiating conference regarding the series direction for the fourth season with CBS chief executive Bill Paley, Allen stormed out (of the meeting) when told that the budget was being cut by 15% from Season Three, his action thereby sealing the show's cancellation.[21]

Robert Hamner, one of the show's writers, states (in Starlog, #220, November 1995) that Paley despised the show so much that the budget dispute was used as an excuse to terminate the series. Years later, Paley stated this was incorrect and that he was a fan of "the Robot".

The Lost in Space Forever DVD cites declining ratings and escalating costs as the reasons for cancellation.[22] Even Irwin Allen admitted that the Season 3 ratings showed an increasing percentage of children among the total viewers, meaning a drop in the "quality audience" that advertisers preferred.[23]

A contributing factor, at least, was that June Lockhart and director Don Richardson were no longer excited about the show. Lockhart said in response to being told about the cancellation by Perry Lafferty, the head of CBS programming, "I think that's for the best at this point", although she goes on to say that she would have stayed if there had been a fourth season. Lockhart immediately joined the cast of CBS' Petticoat Junction upon Lost in Space's cancellation. Richardson had been tipped off that the show was likely to be cancelled, was looking for another series, and had decided not to return to Lost in Space, even if it continued.

Guy Williams grew embittered with his role on the show as it became increasingly "campy" in Seasons 2 and 3 while centering squarely on the antics of Harris' Dr. Smith character. Whether Williams would have returned for a fourth season or not wasn't revealed, but he never acted again after the series, choosing instead to retire to Argentina.[24]

Music

The open and closing theme music was written by John Williams, the composer behind the Star Wars theme music, who was listed in the credits as "Johnny Williams".

The original pilot and much of Season One reused Bernard Herrmann's eerie score from the classic sci-fi film The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951).

For Season Three, the opening theme was revised (again by Williams) to a more exciting and faster tempo score, accompanied by live action shots of the cast, featuring a pumped-up countdown from seven to one to launch each week's episode. Seasons 1 and 2 had animated figures "life-roped" together drifting "hopelessly lost in space" and set to a dizzy and comical score that Bill Mumy once described in a magazine interview as "sounding like a circuit board".

Much of the incidental music in the series was written by Williams who scored his four TV episodes with the movie soundtrack quality that not only helped him gain credibility and a boost towards his later success but also gave Lost in Space its distinctive musical style that is instantly recognizable by all of the shows fans. Other notable film and television composers included Alexander Courage (composer of the Star Trek theme), who contributed six scores to the series. His most recognizable ("Wild Adventure") included his key theme for "Lorelei" composed for organ, woodwinds, and harp — thus cementing this highly recognizable theme with Williams' own "Chariot" and the main theme for the series. The dramatic music of the show served the serious drama episodes well while highlighting the whimsy of later episodes when the deadly serious tunes were used to underscore comical and laughable fantasy threats.

Lost In Space Vol. 1

GNP Crescendo released the first album in 1997 as part of The Fantasy Worlds Of Irwin Allen, featuring music from "The Reluctant Stowaway" (tracks 2-5), "Island In The Sky" (tracks 6 and 7) and "The Hungry Sea" (tracks 8-10).

All music composed by John Williams.

- Lost In Space Main Title (:56)

- Smith's Evening/Judo Chop/On The Pad/Countdown (8:54)

- Escape Velocity/Robot Control/Meteor Storm/Defrosting (7:58)

- The Weightless Waltz (2:30)

- The Monster Rebels/A Walk In Space/Finale (7:49)

- Suiting Up/Stranglehold/The Landing/Search For John (12:20)

- Tractor Play-on/Electric Sagebrush/Will Is Threatened (2:30)

- The Earthquake (2:44)

- Chariot Titles/Fahrenheit A Go-Go/The Chariot Continues/Sunstorm (3:41)

- Morning After/The Inland Sea/Land Ho/Strange Visitor (7:54)

- Lost In Space End Title (:50)

Lost In Space Vol. 2

GNP Crescendo released the second album in 1997 as part of the abovementioned set, featuring music from "Wild Adventure" (tracks 2-4), "The Haunted Lighthouse" (tracks 5 and 6) and "The Great Vegetable Rebellion" (tracks 7 and 8).

Tracks in bold contain themes composed by John Williams.

- Lost In Space Main Title: Season 3 - John Williams (1:03)

- Million Miles/Dust Ball/Episode Titles - Alexander Courage (2:36)

- Pushy Fellow - Alexander Courage (2:40)

- Flying "A" Statin/Floating Lady/The Big Whew/Irwin Van Belt - Alexander Courage (8:48)

- Opening Scene/J-5/Take-Off/F-12/Colonel Fogey/Penny And J-5/A Zaybo For Smith/Turkey Dinner/Act-Out on J-5 - Joseph Mullendore (10:30)

- J-5 Listens to Penny/J-5 to the Rescue/Last Scene - Joseph Mullendore (4:22)

- A Plant Planet - Alexander Courage (2:39)

- Episode Titles/Howling Hyacinths/The Vegetable/Sprouting Smith/Vic's Smithy/Judy's Goat/The Dry Boys/Caught by a Carrot - Alexander Courage (11:43)

- Lost In Space End Title: Season 3 - John Williams (:51)

Lost In Space Vol. 3

GNP Crescendo released the third album in 2000, featuring music from "The Derelict" by Richard LaSalle, Herman Stein and Hans J. Salter (tracks 1 and 3-11) and "My Friend Mr. Nobody" by John Williams (tracks 12-17).

Single-asterisked cues by Richard LaSalle. **by Herman Stein. ***by Hans J. Salter.

Tracks in bold contain themes composed by John Williams.

- Rescued From Space*/The Comet Cometh** (8:36)

- Lost In Space Main Title: Season 1 - John Williams (:58)

- Derelict Title**/Don Rescues John and Maureen* (5:30)

- The Road Performs* (1:19)

- Writing In The Log*/Family** (1:58)

- The Treatment*/Swallowed** (4:18)

- Flashing Lights***/Frontal Robotomy*** (:39)

- Filmy Spider Web***/Crystalline Power Source*** (3:30)

- Smart Kid***/Bubble Monster* (5:30)

- Lift Off*** (4:21)

- New Planet*/Continued Next Week** (01:34)

- Wonderland Discovery (2:58)

- Hairstyle Book/Penny's Friend/Diamonds/Penny/Diamond Play Off (4:13)

- Penny's Cave/To The Cave/Gathering Wild Flowers/Moving Rocks (5:44)

- Mother & Daughter/Penny's Problem (5:54)

- Storm Coming Up/A New Galaxy (3:57)

- Lost In Space End Credits: Season 1 - John Williams (:53)

- Lost In Space Unused 2nd Season Main Title - Warren Barker (:48)

Lost In Space 40th Anniversary Edition

In 2005 La-La Land Records released a two-disc set covering many of the series' composers. Cues in bold are previously unreleased.

Disc 1: "The Reluctant Stowaway" (tracks 2-7), "Island In The Sky" (tracks 8-15), "The Hungry Sea" (tracks 16-19) and "My Friend Mr. Nobody" (tracks 20-21); all music by John Williams. Although all four episodes were represented on the previous albums, not all of the music is replicated here.

- Lost In Space Season 1 Main Title (:53)

- Smith's Entrance (2:45)

- Final Countdown (4:33)

- Escape Velocity/Meteor Storm (5:41)

- Weightless Waltz (3:37)

- Monster Rebels (3:40)

- Walk In Space/To Be Continued (7:35)

- Strange Planet/John's Descent (1:30)

- Helmet It (1:19)

- Strangle Hold/Landing (6:24)

- Lil’ Will And The Robot (1:29)

- Search For John (4:13)

- Monkey's Doo (4:52)

- Operation Rescue (1:16)

- Personal Chauffeur/Electric Sagebrush/Will Is Threatened (2:34)

- Earthquake (2:45)

- Temperature Rising/Boring Company/Don's Rays (4:08)

- Warming Rays/Sun Storm (3:00)

- Land Ho/Kid's Play-Off (2:36)

- Wonderland Discovery/Penny's Problem/Gathering Wild Flowers (9:33)

- New Galaxy (2:26)

- Lost In Space Season 1 End Title (:50)

Disc 2

- "CBS Presents This Special Program In Color" (:08)

- Lost In Space Season 3 Main Title - John Williams (1:02)

- "The Derelict": Derelict Title (Herman Stein)/Frontal Robotomy (Hans J. Salter)/Family (Herman Stein)(2:00)

- "There Were Giants In The Earth": Microscope/Pod Almighty - Herman Stein (1:49)

- "Welcome Stranger": Stranger/Friend Or Foe/Permission/Spore Sprayer/The Robinsons/Upper-Ration/Hapgood/Star Charts (Frank Comstock)/Tall Tail/Blast Off (Frank Comstock) - Herman Stein except where indicated (17:33)

- Lost In Space Season 3 Bumper - John Williams (:05)

- "Blast Off Into Space": The Family/Quake/Mine Entrance/Galaxies Wins/Spilled Cosmonium/It's Alive/Cosmonium Fiend/One Last Check/Family/Blast Off/Thruster Control Short/Thruster Control Continued/Freeze Frame - Leith Stevens (15:58)

- "The Curse Of Cousin Smith": Mississippi Shuffle - Robert Drasnin (1:28)

- "The Curse Of Cousin Smith": Little Joe's Yes - Robert Drasnin (1:22)

- "Girl From The Green Dimension": Mulberry Bush/What A Knight - Alexander Courage (4:26)

- "Cave Of The Wizards": Mummy's Boy/Draconian Anthem/King Queen - Alexander Courage (5:16)

- "Collision Of Planets": The Aliens/Sampson March/1st Blast - Gerald Fried (3:27)

- "The Promised Planet": Space-A-Delic - Pete Rugolo (3:50)

- Senior - from "The Sky Pirate" (Leigh Harline)/Introduction - from "Ghost In Space" (Leigh Harline)/The Search - from "The Sky Pirate" (Lionel Newman) (3:58)

- "The Sky Pirate": A Nice Little Bank/Investigation (Cyril Mockridge) (2:52)

- "Space Circus": Terror Stinger/Another World/Ominous Signs/Awful Monster/Silly Monster - Fred Steiner (8:02)

- "Forbidden World": Space Walk - Robert Drasnin (:39)

- Lost In Space Season 2 Main Title (unused) - Warren Barker (:58)

- Lost In Space Season 3 End Title - John Williams (1:09)

"Space-A-Delic" was previously released as part of the bonus CD in the box set The Fantasy Worlds Of Irwin Allen.

Lost In Space: 50th Anniversary Soundtrack Collection

In 2015 La-La Land Records issued a 12-disc boxed set of music from the series, featuring all the episode scores and the tracked-in music for the unaired pilot "No Place To Hide" (which used music by Bernard Herrmann, Leigh Harline and Lionel Newman).

Legal questions

In 1962, Gold Key comics (formerly Dell Comics), a division of Western Publishing Company, began publishing a series of comic books under the title, Space Family Robinson. The story was largely inspired by The Swiss Family Robinson but with a space-age twist. The movie and television rights to the comic book were then purchased by noted television writer Hilda Bohem (The Cisco Kid), who created a treatment under the title, Space Family 3000.

In July 1964, science fiction writer and filmmaker Ib Melchior began pitching a treatment for a feature film, also under the title Space Family Robinson. There is debate as to whether or not Allen was aware of the Melchior treatment. It is also unknown whether Allen was aware of the comic book or the Hilda Bohem treatment.

As copyright law only protects the actual expression of a work, and not titles, general ideas or concepts, in 1964 Allen moved forward with his own take on Space Family Robinson, with characters and situations notably different from either the Bohem or the Melchior treatments (none of the three treatments contained the characters of Smith or the Robot).

Intended as a follow up to his first successful television venture, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Allen quickly sold his concept for a television series to CBS. Concerned about confusion with the Gold Key comic book, CBS requested that Allen come up with a new title. Nevertheless, Hilda Bohem filed a claim against Allen and CBS Television shortly before the series premiered in 1965.

A compromise was struck as part of a legal settlement. In addition to an undisclosed sum of money, Western Publishing would be allowed to change the name of its comic book to Lost in Space.

There were no other legal challenges to the title until 1995, when New Line Cinema announced their intention to turn Lost in Space into a big budget motion picture. New Line had purchased the screen rights from Prelude Pictures (which had acquired the screen rights from the Irwin Allen Estate in 1993). At that time, Melchior contacted Prelude Pictures and insisted that Lost in Space was directly based upon his 1964 treatment. Melchior was aided in his efforts by Ed Shifres, a fan who had written a book entitled Space Family Robinson: The True Story (later reprinted with the title, Lost in Space: The True Story). The book attempts to show how Allen allegedly plagiarized Melchior's concept, with two outlines presented side-by-side.

To satisfy Melchior, Prelude Pictures hired the 78-year-old filmmaker as a consultant on their feature film adaptation. This accommodation was made without the knowledge or consent of the Irwin Allen Estate or Space Productions, the original copyright holder of Lost in Space. Melchior's contract with Prelude also guaranteed him 2% of the producer's gross receipts, a provision that was later the subject of a suit between Melchior and Mark Koch of Prelude Pictures. Although an Appellate Court ruled partly[25] in Melchior's favor, on November 17, 2004, the Supreme Court of California[26] denied a petition by Melchior to further review the case.

No further claim was made and Space Productions now contends that Allen was the sole creator of the television series Lost in Space.

Melchior died on March 14, 2015 at the age of 97.

Guest stars

During its three-season run, many actors made guest appearances, including familiar actors and/or actors who went on to become well-known. Among those appearing in Lost in Space episodes: Joe E. Tata, Kevin Hagen, Alan Hewitt, Warren Oates, Don Matheson, Kurt Russell, Ford Rainey, Wally Cox, Grant Sullivan, Norman Leavitt, Tommy Farrell, Mercedes McCambridge, Lyle Waggoner, Albert Salmi, Royal Dano, Strother Martin, Michael J. Pollard, Byron Morrow, Arte Johnson, Fritz Feld, John Carradine, Al Lewis, Hans Conried, Dennis Patrick, Michael Rennie among many others. Future Hill Street Blues stars, Daniel J. Travanti (billed as "Danny Travanty") and Michael Conrad, made guest appearances on separate episodes. While Mark Goddard was playing Major West, he had a guest appearance as well. Jonathan Harris, although a permanent cast member, was listed in the opening credits as "Special Guest Star" of every episode of Lost in Space.

Syndication

Despite never reaching the 100 episodes desired for daily stripping in syndication, Lost in Space was picked up for syndication in most major U.S. markets. By 1969, the show was declared to be the #1 syndicated program (or close to it) in markets such as Houston, Milwaukee, Miami and even New York City, where it was said that the only competition to Lost in Space was I Love Lucy.[27] The program didn't have the staying power throughout the 1970s of its supposed rival, Star Trek. Part of the blame was placed on the first season of Lost in Space being in black-and-white, while a majority of American households at the time had a color television receiver. By 1975, many markets began removing Lost in Space from daily schedules or moving it to less desirable time slots. The series experienced a revival when Ted Turner acquired it for his growing TBS "superstation" in 1979. Viewer response was highly positive, and it became a TBS mainstay for the next five years.[23]

Documentaries

In the 1990s Kevin Burns, a long time fan of Irwin Allen's works, produced two documentaries.

The Fantasy Worlds of Irwin Allen

In 1995, Kevin Burns produced a documentary showcasing the career of Irwin Allen. Hosted by Bill Mumy and June Lockhart in a recreation of the Jupiter 2 exterior set and utilizing the "Celestial Department Store Ordering Machine" as a temporal conduit to show information and clips on Irwin's history. Clips from Irwin's various productions as well as pilots for his unproduced series were presented along with new interviews with cast members of Irwin's shows. Mumy and Lockhart complete their presentation and enter the Jupiter 2, following which Jonathan Harris appears in character as Smith and instructs the Robot once again to destroy the ship as per his original instructions "...and this time get it right, you bubble-headed booby".

Lost in Space Forever

In 1998, Burns produced a television special about the series hosted by John Larroquette and Robot B-9 (performed by actor Bob May and voice actor Dick Tufeld). The special was hosted within a recreation of the Jupiter 2 upper deck set. The program ends with Laroquette mockingly pressing a button on the Amulet from "The Galaxy Gift" episode, disappearing and being replaced by Mumy and Harris as an older Will Robinson and Zachary Smith. They attempt one more time to return to Earth but find that they are "Lost in Space... Forever!"

Spin-offs

Comics

Before the television series appeared, a comic book named Space Family Robinson was published by Gold Key Comics, written by Gaylord Du Bois and illustrated by Dan Spiegle. (Du Bois did not create the series, but he became the sole writer of the series once he began chronicling the Robinsons' adventures with "Peril on Planet Four" in issue #8, and he had already written the Captain Venture second feature beginning with "Situation Survival" in issue #6). Due to a deal worked out with Gold Key, the title of the comic later incorporated the Lost in Space sub-title. The comic book featured different characters and a unique H-shaped spacecraft rather than one of a saucer shape.

There is an unlicensed comic in which Will Robinson meets up with Friday the 13th character Jason Voorhees.

In 1991 Bill Mumy provided "Alpha Control Guidance" for a Lost in Space revival in comic book form Lost in Space comic book for Innovation Comics, writing six of the issues. The first officially licensed comic to be based on the TV series (as the previous Gold Key version was based on the 1962 concept), the series was set several years after the show. The kids were now teenagers, with Will at 16 years old, and the stories attempted to return the series to its straight adventure roots with one story even explaining the camp / farce episodes of the series as fanciful entries in Penny's Space Diary. Complex adult-themed story concepts were introduced and even included a love triangle developing between Penny, Judy and Don. Mark Goddard wrote a "Don" story, something he never had in the original series (with the possible exception of "the Flaming Planet" which might qualify as a "Don" episode). The Jupiter 2 had various interior designs in the first year as artists were obviously not familiar with the original layout of the ship while Michal Dutkiewicz got it 'spot-on'. The first year had an arc ultimately leading the travelers to Alpha Centauri with Smith contacting his former alien masters along the way. Aeolis 14 Umbra were furious with Smith for not having succeeded in his mission to prevent the Jupiter 2, built with technology from a crashed ship of their race, from reaching the star system they had claimed as their own. The year ended with Smith caught out for his traitorous associations and imprisoned in a freezing tube for the Jupiter's final journey to the Promised Planet. Year two was to be Mumy's own full season story of a complex adventure following the Robinson's arrival at their destination and capture by the Aoleans. Innovation folded in 1993 with the story only halfway through and it wasn't until 2005 that Mumy was able to present his story to Lost in Space fandom as a complete graphic novel via Bubblehead Publishing. The theme of an adult Will Robinson was also explored in the film and in the song "Ballad of Will Robinson"—written and recorded by Mumy.

In 1998 Dark Horse Comics published a three-part story chronicling the Robinson Clan as depicted in the film.

In 2006 Bill Mumy and Peter David co-wrote Star Trek: The Return of the Worthy, a three-part story that was essentially a crossover between Lost in Space and Star Trek with the Enterprise crew encountering a Robinson-like expedition amongst the stars, though with different characters.

In 2016, American Gothic Press published an six-issue miniseries which are based on unfilmed scripts from the series.[28]

Novel

In 1967, a novel based on the series, with significant changes to the personalities of the characters and the design of the ship, was published by Pyramid Books, and written by Dave Van Arnam and Ted White (as "Ron Archer"). A scene in the book correctly predicts Richard Nixon winning the Presidency after Lyndon Johnson.

Cartoon

In the 1972–1973 television season, ABC produced The ABC Saturday Superstar Movie, a weekly collection of 60-minute animated movies, pilots and specials from various production companies, such as Hanna-Barbera, Filmation, and Rankin-Bass – Hanna-Barbera Productions contributed animated work based on such television series as Gidget, Yogi Bear, Tabitha, Oliver Twist, Nanny and the Professor, The Banana Splits, and Lost in Space. Dr. Smith (voiced by Jonathan Harris) was the only character from the original program to appear in the special, along with the Robot (who was named Robon and employed in flight control rather than a support activity). The spacecraft was launched vertically by rocket, and Smith was a passenger rather than a saboteur. The pilot for the animated Lost in Space series was not picked up as a series, and only this episode was produced. This cartoon was included in the Blu-ray release on September 15, 2015.

Feature film

In 1998, New Line Cinema produced a Lost in Space feature film. It included numerous nods, homages and cameos related to the series, including:

- Dick Tufeld as The Robot's voice

- Mark Goddard played the military general who gives Major West his orders for the mission

- June Lockhart played the principal of Will Robinson's school

- Angela Cartwright and Marta Kristen appeared as reporters

- A CG animated alien primate character, in homage to the original Debbie "the Bloop" space-ape pet

- The film's Jupiter 2 was launched into orbit by a vehicle called the Jupiter 1, which closely mimics the series' spacecraft, complete with rotating propulsion lights

- Reference is made to the Chariot and Space Pod, both of which are reported wrecked

Additional cameo appearances from the original series were considered, but did not make it to the film: Harris was offered a cameo appearance as the Global Sedition leader who hires, then betrays, Smith. He turned down the role, which eventually went to Edward Fox, and is even reported to have said "I play Smith or I don't play." Harris appeared on an episode of Late Night with Conan O'Brien, mentioning that he was offered a role: "Yes, they offered me a part in the new movie — six lines!"

The film used a number of ideas familiar to viewers from the original show. Smith reprogramming the robot and its subsequent rampage (Reluctant Stowaway), near miss with the sun (Wild adventure), the derelict spaceship (The Derelict), discovery of the Blawp and the crash (island in the Sky) and an attempt to change history by returning to the beginning (The Time Merchant). Also a scene-stealing 'Goodnight' homage to the Waltons was included. Something fans of the original always wanted to see happen was finally realized when Don gives Smith a crack at the end of the movie: "That felt good!"

Second television series

In late 2003, a new television series, with a somewhat changed format, was in development in the U.S. It originally was intended to be closer to the original pilot with no Smith, but including a robot, had an additional older Robinson child called David, and Penny was a mere baby. The pilot (titled, "The Robinsons: Lost in Space") was commissioned by The WB Television Network. It was directed by John Woo and produced by Synthesis Entertainment, Irwin Allen Productions, Twentieth Century Fox Television and Regency Television.

The Jupiter 2 interstellar flying-saucer spacecraft of the original series was changed to a non-saucer planet-landing craft, deployed from a larger inter-stellar mothership.

The cast included Brad Johnson as John Robinson, Jayne Brook as Maureen Robinson, Adrianne Palicki as Judy Robinson, Ryan Malgarini as Will Robinson, and Mike Erwin as Don West.

In this adaptation John Robinson was a retiring war hero of an alien invasion and had decided to take his family to another colony elsewhere in space. However the ship is attacked by the aliens, David is lost amidst it all, and the Robinsons, along with Don, are forced to escape in the small Jupiter 2 "Space Pod" of the mothership. The series, presumably, would have revolved around the family trying to recover David from the aliens. The one surviving performer from the original series was Dick Tufeld, once again reprising his role as voice of the robot for the 3rd time, in Lost in Space's 3rd live-action incarnation after the original pilot.

It was not among the network's series pick-ups confirmed later that year.

The producers of the new Battlestar Galactica show bought the show's sets. They were redesigned the next year and used for scenes on the Battlestar Pegasus.

Third television series version in development

On October 10, 2014, it was announced that Legendary TV was developing a new reboot of Lost in Space for Netflix with Dracula Untold screenwriters Matt Sazama and Burk Sharpless attached to write.[29][30] On June 29, 2016, Netflix ordered the series with 10 episodes.[31][32]

DVD and Blu-ray releases

20th Century Fox has released the entire series on DVD in Region 1. Several of the releases contain bonus features including interviews, episodic promos, video stills and the original un-aired pilot episode.

| DVD name | Ep# | Release date |

|---|---|---|

| Season 1 | 30 | January 13, 2004 |

| Season 2 Volume 1 | 16 | September 14, 2004 |

| Season 2 Volume 2 | 14 | November 30, 2004 |

| Season 3 Volume 1 | 15 | March 1, 2005 |

| Season 3 Volume 2 | 9 | July 19, 2005 |

All episodes of Lost in Space were remastered and released on a Blu-ray disc set on September 15, 2015 (the 50th anniversary of the premiere on the CBS TV Network). The Blu-ray disc set includes a cast table reading of the final episode, written by Bill Mumy, which brings the series to a close by having the characters return to earth.

Title in other languages

- Brazilian Portuguese: Perdidos no Espaço

- Croatian: Izgubljeni u svemiru

- Finnish: Matkalla avaruuteen

- French: Perdus dans l'espace

- German: Verschollen zwischen fremden Welten (= Lost/Missing between strange worlds)

- Greek: Χαμένοι στο διάστημα

- Hebrew: אבודים בחלל

- Japanese: 宇宙家族ロビンソン (Uchuu Kazoku Robinson = Space Family Robinson)

- Korean: 우주가족 로빈슨 (Uju Gajok Robinseun = Space Family Robinson)

- Polish: Zagubieni w kosmosie

- Romanian: Pierduți în spațiu

- Spanish: Perdidos en el espacio

- Slovenian:Izgubljeni v vesolju

- Welsh: Ar goll yn y Gofod

References

- ↑ Abbott, Jon (2009). Irwin Allen Television Productions, 1964-1970: A Critical History of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel and Land of the Giants. Jefferson: Mcfarland. p. 113. ISBN 0786444916.

- ↑ Frederick S. Clarke Cinefantastique - Volume 29, N o 12 -1998 Page 27 "The cast of characters in the original, unaired pilot for LOST IN SPACE (entitled "No Place to Hide") included neither the robot nor Dr. Zachary Smith. The Robinsons load the Chariot to move to a better... "

- ↑ Val Patterson. "The Bloop from Lost in Space". rockypatterson.com.

- ↑ in the third season episode, "The Kidnapped of Space"

- ↑ Jon Abbott (3 October 2006). Irwin Allen Television Productions, 1964-1970: A Critical History of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel and Land of the Giants. McFarland. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-0-7864-8662-5.

- 1 2 3 "Science Fiction." Pioneers of Television, January 18, 2011.

- 1 2 YouTube. youtube.com.

- ↑ ""The Chariot" from Lost In Space". Car Lust. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ "First Season Chariot COLOR Footage". YouTube. 26 May 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ "RacProps Issue 1 - Lost In Space". racprops.com.

- ↑ "Spinoff Frequently Asked Questions". NASA.gov.

- ↑ Eisner, Joel, and Magen, Barry, Lost in Space Forever, Windsong Publishing, Inc., 1992.

- ↑ "Science Fiction Programming" at the Museum of Broadcast Communications online

- ↑ Gowran, Clay. "Nielsen Ratings Are Dim on New Shows." Chicago Tribune. Oct. 11, 1966: B10.

- ↑ Gould, Jack. "How Does Your Favorite Rate? Maybe Higher Than You Think." New York Times. Oct. 16, 1966: 129.

- ↑ Source: Starlog magazine

- ↑ Aladino V. Debert (1998). "Visual Effects Headquarters Archive: Lost in Space". Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ Eisner, Joel, and Magen, Barry, "Lost in Space Forever," p. 279, Windsong Publishing, Inc., 1992.

- ↑ "Lost in Space" (1965) at IMDB.com

- ↑ Lost in Space at tv.pop-cult.com

- ↑ Eisner, Joel, and Magen, Barry, Lost in Space Forever, p. 280, Windsong Publishing, Inc., 1992.

- ↑ Lost in Space Forever, DVD, Twentieth Century Fox, 1998.

- 1 2 "Galaxy Beings Maveric Lions: The History of TVs Lost in Space". galaxybeingsmavericlions.blogspot.com.

- ↑ "12 Fun Facts about Lost in Space at www.neatorama.com

- ↑ "Microsoft Word – B153239.DOC" (PDF).

- ↑ "California Courts - Home". ca.gov.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Lost in Space Fandom at lisfanpress.com

- ↑ Bennett, Jason (March 17, 2016). "First Look – Irwin Allen’s Lost in Space: The Lost Adventures #1 from American Gothic Press".

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (October 9, 2014). "Lost In Space: Reboot In The Works At Legendary TV With Dracula Writers". Deadline.com. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Ching, Albert (November 20, 2016). "Lost in Space Remake in Development at Netflix". Spinoff.comicbookresources.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (June 29, 2015). "Lost In Space Remake Picked Up To Series By Netflix". Deadline.com. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Redmon, Stuart (June 30, 2016). "Netflix's Lost in Space Remake Coming in 2018". Nerd Much?. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lost in Space (television program). |

- Perdidos no Espaço

- Lost in Space

- Lost in Space on IMDb

- Lost in Space at TV.com

- Penny Robinson Fan Club

- Forum for Lost in Space

- How the Lost in Space standard issue raygun prop was made