Loring Air Force Base

| Loring Air Force Base | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limestone Air Force Base | |||||||||

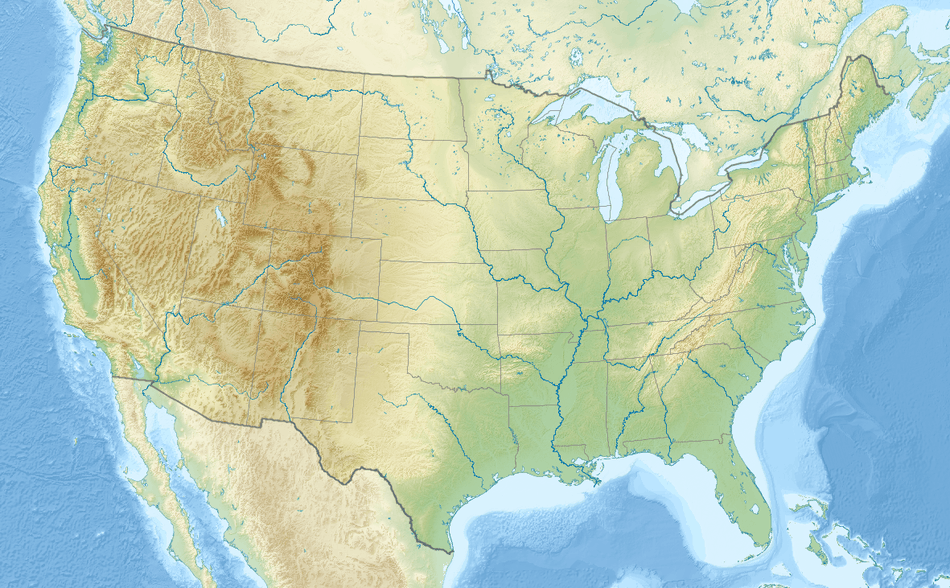

| near Limestone and Caswell, Maine in United States | |||||||||

|

USGS 1970 Aerial Photo | |||||||||

|

Logo of Air Combat Command | |||||||||

Loring AFB (KLIZ)  Loring AFB (KLIZ) Location of Loring AFB | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 46°56′59″N 67°53′20″W / 46.94972°N 67.88889°WCoordinates: 46°56′59″N 67°53′20″W / 46.94972°N 67.88889°W | ||||||||

| Type | Air Force Base | ||||||||

| Area | 9,000 acres (14.1 sq mi; 36.4 km2) | ||||||||

| Site information | |||||||||

| Owner | United States Air Force | ||||||||

| Operator | 42nd Bomb Wing | ||||||||

| Controlled by |

| ||||||||

| Open to the public | Yes | ||||||||

| Stations | Caribou Air Force Station (East Loring), Caswell Air Force Station | ||||||||

| Site history | |||||||||

| Built | 1947-53 | ||||||||

| Built by | United States Army Corps of Engineers | ||||||||

| In use | 1950–1994 | ||||||||

| Fate | Mainly intact, partial demolition | ||||||||

| Events | Cold War | ||||||||

| Garrison information | |||||||||

| Current commander | Robert J. Pavelko | ||||||||

| Garrison | 42nd Bomb Wing | ||||||||

| Occupants | 69th Bombardment Squadron, 70th Bombardment Squadron, 75th Bombardment Squadron, 42d Air Refueling Squadron, 407th Air Refueling Squadron, 2192nd Communications Squadron, 101st Fighter Squadron | ||||||||

| Airfield information | |||||||||

| Identifiers | IATA: KLIZ, ICAO: LIZ | ||||||||

| Elevation | 746 ft (227 m) AMSL | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Loring Air Force Base (IATA: LIZ, ICAO: KLIZ) was a United States Air Force installation in northeastern Maine, near Limestone and Caribou in Aroostook County. It was one of the largest bases of the U.S. Air Force's Strategic Air Command during its existence, and was transferred to the newly created Air Combat Command in 1992.

The base's origins began in 1947 with an order for construction of an airfield by the New England Division of the United States Army Corps of Engineers. The chosen site, in northeastern Maine within both Limestone Township and Caswell Plantation, was the closest point in the continental U.S. to Europe, providing high strategic value during the Cold War. The base was originally named Limestone Army Air Field, and was renamed Limestone Air Force Base following the establishment of the Air Force in 1947. It was named in 1954 for Major Charles J. Loring, Jr., USAF, a Medal of Honor recipient during the Korean War. From 1951 to 1962, it was co-located next to Caribou Air Force Station.

Loring was home to a civilian population, many of whom were employed alongside active duty service members. The base included many amenities, such as a hospital, school, and ski hill, which facilitated the adjustment to Maine life by the civilians.

The 1991 Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommended that Loring be closed and its aircraft and mission be distributed to other bases in the nation. The base was closed in September 1994 after over forty years of service. It was redeveloped by the Loring Development Authority as the Loring Commerce Centre, an industrial and aviation park; the airfield is operated as Loring International Airport.

Overview

For the majority of its operational lifetime, Loring was a heavy bomber, aerial refueling, and interception facility for military aircraft, equipment, and supplies first as part of Strategic Air Command (SAC) (1947–1992), then as part of the succeeding Air Combat Command (ACC) (1992–1994).[1]

Loring was planned in 1947 as Limestone Army Air Field and was designed with a capacity of over 100 B-36 Peacemaker strategic bombers. This plan was only partially completed due to budget constraints, but, over time, Loring became one of the largest air bases of SAC. After the B-36 was phased out, the B-52 Stratofortress was based at Loring, first with D models, then with B-52Gs. The Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter was also based there for a number of years, until it was replaced by the better-known KC-135A Stratotanker.[1]

Loring was also home to many facilities that were a part of the base, or were nearby. Caribou Air Force Station was the weapons storage area that operated separately from Loring until it was absorbed in 1961.[1] Caswell Air Force Station operated to the east, but had a unit associated with Loring before it became fully operational. On-base facilities included the Alert Area, which operated as a separate facility within Loring, due to crews being constantly stationed on alert.[2] The Double Cantilever Hangar was the largest hangar at the facility, with the capacity to hold six parked B-52s, or five B-36s.[3]

One of Loring's major secondary missions included serving as the headquarters for the 45th Air Division from 8 October 1954 to 18 January 1958, and on 20 November 1958. The host wing at Loring was the 42d Bombardment Wing for all but a small portion of its early existence. Loring was primarily home to active duty units, although this changed in the 1980s, when the Massachusetts Air National Guard's 101st Fighter Squadron sent a detachment to Loring. As the base was the closest in the U.S. to Europe, it also functioned as an important stopover point.[1]

The 1991 Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommended closure of Loring AFB and it was officially closed in September 1994.[1] It was later reopened as the Loring Commerce Centre.[4]

Major units

42nd Bomb Wing

The 42nd Bomb Wing was the host unit at Loring AFB from 1953 until 1994, supporting national security objectives with mission-ready B-52G Stratofortresses, and KC-135 Stratotanker aircraft. The wing had the ability to deploy at any time to support both SAC, and later, ACC missions. It was operational at Loring from 1953 to 1994.[5]

The 42nd Operations Group (OG) formerly supported national security objectives, as directed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, utilizing B-52 and KC-135 aircraft. Operational squadrons during the time of its operation at Loring included:[5]

- 69th Bombardment Squadron (B-52, 1952–1991)

- 70th Bombardment Squadron (B-52, 1953–1966)

- 75th Bombardment Squadron (B-52, 1953–1956)

- 42d Air Refueling Squadron (KC-135, 1955–1994)

- 407th Air Refueling Squadron (KC-135, 1968–1990)

All B-52s carried the "LZ" Tailcode. In addition to the 42nd OG, other components of the 42nd Bomb Wing were:[5]

- 42nd Organizational Maintenance Squadron

- 42nd Field Maintenance Squadron

- 42nd Avionics Maintenance Squadron

- 42nd Munitions Maintenance Squadron

- 42nd Combat Support Group

- 42nd Transportation Squadron

- 42nd Supply Squadron

- 42nd Civil Engineering Squadron

- 42nd Consolidated headquarters Squadron

- 42nd Security Police Squadron

- 42nd Airborne Missile Maintenance Squadron (1964–1974), responsible for maintenance of missiles that were fitted onto the B-52s

- 2192nd Communications Squadron, Air Force Communications Command unit absorbed into 42nd Bomb Wing in 1990

In 1991, it was announced that Loring would close in 1994. This led to the 42nd being moved to Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama, where it became the 42nd Air Base Wing.[6] All other squadrons of the wing were inactivated and have remained inactive, except for the 69th, which was reactivated in 2009 at Minot Air Force Base.[7]

History

Loring AFB was named in 1954 for Major Charles J. Loring, Jr., USAF, a Medal of Honor recipient during the Korean War. During the morning of 22 November 1952, he led a flight of F-80 Shooting Stars on patrol over Kunwha. After beginning a dive bombing run and getting hit, he entered into a controlled dive and destroyed a Chinese gun emplacement on Sniper Ridge that was harassing United Nations troops. Limestone Air Force Base was renamed in his honor.[1]

Previous designations

Designations of Loring Air Force Base:[1]

- Limestone Army Air Field (15 April 1947 – 5 June 1950)

- Limestone Air Force Base (5 June 1950 – 1 October 1954)

Major commands assigned

Major commands to which the base was assigned:[1]

- Strategic Air Command, 15 April 1947 – 1 June 1992

- Air Combat Command, 1 June 1992 – 30 September 1994

Major units assigned

Major units which were assigned to Loring:[5]

|

|

Operational history

Origins

Loring AFB was carved out of the woods of Maine beginning in the late forties and officially dedicated in 1953, named after Charles J. Loring, Jr., who was killed in the Korean War. The closest Air Force base on the east coast to Europe, it was originally built with a capacity of 100 B-36 Peacemaker bombers and equipped with a 10,000-foot (3,000 m) runway.[1][8]

Loring was built on 14,300 acres (58 km2) of land, making it the biggest SAC base in the country. This in turn allowed for it to have the largest capacity for weapon storage and for fuel storage in all of SAC. (Its overall capacity ranked second among all 21 SAC bases). The weapons storage capacity was the highest in all of SAC, 10,247,882 NEW (Net Explosive Weight), and it was first in all of SAC in fuel storage capacity (9,193,374 gallons).[8] Fuel was delivered to the base via a 200-mile pipeline to Searsport, Maine.[9] Ramp space at Loring exceeded 1.1 million square yards, which made it second among all SAC bases in total ramp space, and first in excess ramp space. Furthermore, it was one of two fully capable conventional weapons storage facilities in CONUS maintained by SAC.[8]

During the Cold War, new U.S. Air Force bases were constructed along the northern border of the continental U.S.; their most direct route to the Soviet Union was through the Arctic Circle. These sites were high-importance strategic bases for hosting long-range missiles and aircraft. In 1947, the New England Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers chose a site in northeastern Maine, within both the Limestone Township and Caswell Plantation. The remote site consisted mostly of dense forest, shallow marshes, and wild blueberry bogs, on a slight plateau over the town, which helped keep it above the fog most of the time. Only a small part of the base was suitable for farming, so there was little impact on Aroostook County's agricultural community. Additionally, Loring was not far from sources of materials for runway, taxiway, and parking apron construction. The most important benefit of the site was that it was a few hundred miles closer than any other base to potential targets in Europe.[1]

Construction

On 15 April 1947, construction commenced on Limestone Army Air Field, the first Strategic Air Command base designed and built to host high-speed aircraft, including the new B-36 Peacemaker. Original plans for Limestone called for two parallel north−south runways, a 12,000-foot (3,660 m) east−west runway, and accommodations for over 100 aircraft. The multimillion-dollar project was not built to the specifications of the original Army Corps of Engineers plan, and only one north−south runway was constructed.[1]

On 23 May, a $17 million contract was awarded to two companies, to complete the first phase of construction. This included the north−south runway, a parallel taxiway (Taxiway J), a parking apron, the Arch Hangar, a base operations building, a control tower, a power plant, a 250-person barracks (which would later become Building 6000), a water supply system, and a railroad spur to the base (now part of the Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway).[1]

One of the first structures was the Arch Hangar. At the time, it was the largest monolithic arch roof structure in the US, and one of the largest hangars in the world. The construction of the hangar was also groundbreaking, including a foundation set on bedrock, extensive footing structures, intricate formwork, and a 340-foot arch span.[1]

The runway was another major construction task. The airfield in northern Maine was subject to freeze-thaw cycles and had bogs and various types of groundcover; 2.1 million cubic yards of material was removed. The foundation of the runway was constructed to a depth of 70 inches (1.78 m) of a flexible bituminous-concrete pavement. This was all done on a runway that was 10,000 feet (3,050 m) in length and 300 feet (90 m) wide.[1]

The month of June 1950 began 44 years of constant activity at Limestone. On the 10th, the 7 officers and 78 airmen of the Limestone Detachment arrived, as the tenant unit during construction. Two days later, an aircraft from Oklahoma arrived. On the 15th, limited operations began at Limestone, as Cold War tensions began to heat up. The next day, a B-36 Peacemaker arrived and later departed. 1 July brought the re-designation of the Limestone Detachment as the 4215th Base Service Squadron. After the Korean War broke out, the decision was made to increase the squadron's size to 28 officers, 340 airmen, and 20 civilians. August brought the first permanently assigned aircraft, a C-47 Skytrain, and more aircraft using the base as a stopover between the States and Europe.[1]

The war brought increased funding to Limestone in 1951. Eight additional hangars were constructed at the southwestern end of the runway, as well as a 2,100-foot (640 m) addition to the northern end of the runway. The Department of Defense allocated funds for the North River Depot, a weapons storage facility to the northwest of the base. It later became Caribou Air Force Station and was absorbed into the facility in the 1960s. The end of the year brought the completion of a communications facility, a hospital, three barracks, a school, an officers club, a bakery, and a briefing and training building. The base was one of the first constructed after World War II and also one of the first to retain as much surrounding vegetation as possible in case there was a need to camouflage the airfield and surrounding facilities. It avoided the traditional grid system for roads.[1]

Hangars were built for the additional aircraft at the base, including the 250-by-600-foot (80 by 180 m) double cantilever hangar, one of the first built by the Air Force in response to a demand for more efficient maintenance space; it could house five B-36 Peacemakers and six B-52 Stratofortresses,[1] and nine planned concrete arch hangars were no longer needed.[10]

The runway was resurfaced in 1955 in anticipation of the arrival of the B-52 Stratofortress in 1956. Eighteen additional "nose-dock" hangars (hangars which could contain the nose and wings of the aircraft, allowing for maintenance to the cockpit area by the crew, without the need to use the larger hangars) were built in 1956 to the northwest of the runway, near the main parking area, along with parking areas and taxiways for these hangars.[1]

Early history

On 8 February 1953, Curtis E. Lemay, Commander of SAC, visited the base to review the construction's progress. During this visit, he indicated that Limestone was operationally ready. Later that month, command capabilities were formally transferred to SAC, ending an almost six-year command by the Army Corps of Engineers. Furthermore, personnel of the 4215th Base Service Squadron were reassigned to the 42d Bombardment Wing, which was reactivated and assigned to the 8th Air Force. On 23 February, Limestone Air Force Base officially became operational.[1]

During the first few months, the wing was not assigned any aircraft, and thus worked with other units who were in possession of the B-36 Peacemaker. In March and April, the base began preparing for operations of the B-36, which arrived later in April. This gave the newly activated 69th Bombardment Squadron a full complement of aircraft. By the end of August, the number had increased to 27 bombers, 322 officers, 313 airmen, and 350 civilians. Additionally, more buildings were constructed on base, making it more of a home for airmen and their families.[1]

January 1954 brought the declaration of the 42nd being capable of implementing its Emergency War Plan. On 1 October, the base was renamed after Charles Loring Jr., and became "Loring Air Force Base". One week later, the 45th Air Division was activated at Loring and designated the primary base unit. It was also designated that month as the primary staging location for fighter aircraft flying out of the Continental United States to and from Europe. Loring had 63 permanent aircraft assigned, and air traffic was significantly increased.[1]

As the Cold War progressed, so did the need for new aircraft and techniques. The first KC-97 Stratofreighter arrived at Loring with the activation of the 42d Air Refueling Squadron in January 1955. The B-36's were not actually equipped to perform aerial refueling, so the planes supported other units until the arrival of the B-52 in 1956. Eventually, 21 tankers were based at Loring, along with 30 air crews.[1]

By 1955, the base consisted of the 42d, 69th, 70th, and the 75th Bombardment Squadrons. A hospital became operational. The next January, a B-52 landed at the airfield as part of a cold weather testing program. Five months later, the first Stratofortress, the "State of Maine", was permanently stationed at Loring.[1]

In November 1956, the Air Force used the base for publicity. On 10 November, the Soviet Union threatened to oust British and French troops from the Middle East, days after the end of the Suez Crisis. After a response by president Dwight D. Eisenhower to the United Nations, a reporter with the Associated Press visited Castle Air Force Base in California after SAC was alerted to support whatever action the U.S. might take. The reporter was unable to find out classified information, and instead invented maintenance records of the fleet that painted a dismal picture. On 24 and 25 November, four B-52's of the 93rd Bombardment Wing and the 42nd flew nonstop around the perimeter of North America in Operation Quick Kick, which covered 15,530 mi (13,500 nmi; 24,990 km) in 31 hours, 30 minutes. SAC noted the flight time could have been reduced by 5 to 6 hours if the four inflight refuelings had been done by fast jet-powered tanker aircraft rather than propeller-driven KC-97 Stratofreighters.[11] After the flight ended, the planes landed at Friendship International Airport. The operation distracted public attention from the reporter's story.[1]

The base was also the location of an experimental system of steam pipes in 1957, to test the viability of using steam to melt the snow on the runways. Pipes were spaced at different intervals in the experiment.[12] That same year, the first KC-135 Stratotanker, christened the "Aroostook Queen", arrived at Loring. By December, all of the KC-97s had left, and by April 1958, 20 KC-135s had arrived, allowing the 42nd Air Refueling Squadron to reach full operational capacity in May. Later that year, an alert force was created at Loring, consisting of six B-52's. The following year, in response to a conflict in Lebanon, the entire wing was placed on alert.[1]

An Alert Force was established at Loring AFB in October 1957. The wing began supporting the force with six B-52s in January 1958. In response to a conflict in Lebanon, the Alert Force was expanded to include the entire bombardment wing in July 1958, when the SAC bomber force went to full alert status. SAC's overall goal was achieved in 1960.[1]

On 11 March 1958, base personnel were the first members of the Air Force to land a B-52 in a wheels-up configuration at Westover AFB near Springfield, Massachusetts. After being lifted up and onto its wheels, the plane was flown to Kelly AFB at San Antonio, Texas, for a complete overhaul and inspection, before it was returned to the 42nd.[13]

Loring was also home to an administrations support base of a Green Pine communications crew from Naval Station Argentia. The detachment did not even officially exist on the base, even though it was located on the top floor of the Bachelors Officers Quarters and consisted of six men.[14]

Assigned aircraft

Various aircraft were assigned to the base, including the massive B-36 Peacemaker, which was assigned to the 42d Bombardment Wing from 1 April 1953 to 6 September 1956; the KC-97G Stratotanker, which was assigned from 15 February 1955 to 16 December 1957; the B-52C Stratofortress, which was assigned 16 June 1956 to January 1957; the |KC-135A Stratotanker, which was assigned from 16 October 1957 to 7 May 1990; the B-52G, which was assigned from January 1957 to 16 November 1993; and the KC-135R, which was assigned from 1990 to March 1994.[15]

Fighter aircraft were also assigned to the base during its operation. The F-102 Delta Dagger, which was assigned to the 27th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, was located on base from 1957 to 1960 while the F-106 Delta Dart was assigned from 16 October 1959 to 1 July 1971,[16] and to the 83d Fighter-Interceptor Squadron from July 1971 to June 1972.[17]

Weapons Storage Area

The Nuclear Weapons Storage Area at Loring once operated as a separate, top secret facility. Originally called the North River Depot, the remote area to the northeast of Loring's property was the first U.S. operational site specifically constructed for the storage, assembly, and testing of atomic weapons.[18]

In 1951, the Department of Defense (DOD) allocated funds for the construction of an ordnance storage site at Loring AFB. The designs called for a self-sufficient "maximum security storage area for the most advanced weapons of mankind". The mission of the facility would be the protection and maintenance of the weapons used by SAC. The facility was in the northeast comer of the base, and construction began on 4 August 1951. In addition to 28 storage igloos and other weapons storage structures, the facility included weapons maintenance buildings, barracks, recreational facilities, a warehouse, and offices.[18]

A parallel series of four fences, one of which was electrified, surrounded the heart of the storage area. This area was nicknamed the "Q" Area, which denoted the Department of Energy's Q clearance required to have access to Restricted Data.[18]

In June 1962, the Atomic Energy Commission released its custody and ownership of the weapons to the Air Force. The personnel and property of the later named Caribou Air Force Station were absorbed into the adjacent Loring Air Force Base.[18]

Nike defense area

To provide air defense of the base, four United States Army Nike-Hercules surface-to-air missile sites were constructed during 1956. Sites were located near Caribou (L-58) 46°53′02″N 068°00′32″W / 46.88389°N 68.00889°W; Caswell (L-13) 47°01′42″N 067°48′35″W / 47.02833°N 67.80972°W; Connor Twp. (L-85) 47°00′29″N 068°01′06″W / 47.00806°N 68.01833°W, and Limestone (L-31) 46°55′04″N 067°47′32″W / 46.91778°N 67.79222°W Maine.[19]

The New England Division of the Army Corps of Engineers managed the construction of these sites. The sites were manned by men from the 3rd Missile Battalion, 61st Air Defense Artillery Regiment, and provided defense for Loring and the northeastern approaches to the United States. In 1960, sites L-13 and L-58 underwent conversion from Ajax missiles to the MIM-14 Nike-Hercules missiles. These sites remained operational until 1966, although the site at Limestone was closed in September 1958.[19]

Members of the 3rd Missile Battalion gained distinction in November 1958 during the Annual Service Practice wargames at Fort Bliss in Texas when they simulated launching 12 Nike Ajax missiles and recorded 12 kills – a United States Army Air Defense Command first.[19]

Operation Head Start

Operation Head Start was conducted at the base from September to December 1958. It helped to demonstrate that a continuous airborne alert could be maintained successfully.[20]

Before each flight, a briefing was held, alerting the crewmembers to basic world events as well as safety criteria. At least 15 hours before takeoff, the crew would thoroughly pre-flight their aircraft. Inadvertently, this also increased efficiency in terms of maintenance and other pre-flight routines.[20]

Every six hours, a bomber would take off with live warheads and continue on a pre-determined path over Greenland and eastern Canada, a trip that ended 20 hours later. Frequently, "Foxtrot: No message required" messages were sent to the bomber from Strategic Air Command headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base, keeping the crews alert.[20]

While entering the landing pattern, crash trucks would travel to the runway and await landing. This was standard procedure for all Head Start landings. After landing, the crew was interrogated prior to being released, so that maintenance, intelligence, and other crews could be alerted to the performance of the plane and other items that the crew might have noticed during their flight. After release, they would typically go to the Physical Conditioning room for a steam bath and rubdown.[20]

Operation Head Start eventually lead to Operation Chrome Dome.[21] Chrome Dome was an operation where bombers would be in constant airborne alert and loiter at points just outside the Soviet Union.[22]

Second-half of the Cold War

Although it is unknown when it was opened, Loring was host to a Conventional Enhanced Release Training bomb range, which was located adjacent to the runway. Loring was one of four Strategic Air Command bases with a range of this type, and it was used frequently. The base was also located next to Condor 1 and Condor 2 airspace, which allowed for low-level training. The routes and training opportunities within the restricted airspace allowed training to be accomplished. One disadvantage of the location of Loring was its distance from the Strategic Training Route Complex and bombing ranges in Nevada and Utah. The ranges out west were the only location where the B-52s were allowed to drop live munitions, although SAC training only required crews to drop live munitions twice a year on these ranges.[8]

In 1974, President Richard Nixon stopped at Loring on 3 July in Air Force One (SAM 27000) as he returned from a summit in Moscow, where he and Leonid Breshnev had signed the Threshold Test Ban Treaty.[23] In a speech in front of 5,000 people in the double cantilever hangar, he talked about the importance of the treaty. President and Mrs. Nixon were welcomed home by vice president Gerald R. Ford, who flew from Washington.[23][24] His daughter Julie Nixon Eisenhower was also in attendance.[25] Nixon resigned from office five weeks later.

On 11 March 1976, SAC headquarters announced that the 42d Bombardment Wing would be inactivated, citing the poor condition of Loring's facilities. In 1976, it was estimated that Loring needed up to $300 million in facilities improvements. Between 1976 and 1979, considerable debate took place over the strategic importance of Loring, resulting in a reversal of the Air Force decision to close Loring. When the decision to keep Loring AFB open was made in 1979, Congress committed itself to upgrading Loring's facilities. After 1981, nearly $300 million in military construction and operations and maintenance funds were spent to upgrade the facilities.[8] Congressman Tip O'Neill of Massachusetts and Senator William Cohen of Maine were firm supporters of the base during the time when it was proposed to be closed.[26]

During the time that Loring was proposed for closure, the region experienced economic uncertainty. Once the Air Force made its intent known in 1976, property values plummeted, and people delayed buying homes, fearing that they would need to relocate. The reduction in the base of around 80% meant that possibly 60% of Aroostook County would need to relocate, according to county officials. A $25,000 study, commissioned by the Department of Labor and conducted at Northeastern University, calculated that the region had lost over $14 million in these three years of economic uncertainty.[27]

On 5 September 1983, members of the 42d Air Refueling Squadron escorted a crippled F-4E Phantom II over the Atlantic Ocean after it experienced the loss of an engine. For its actions, crew E-113 received the Mackay Trophy for refueling it four times and towing it with its refueling boom.[28][29][30]

In 1988, the Air Force decided to close three of its nuclear weapons stations at its SAC bases. In addition to Loring, other bases around the world were scaled back. As the B-1B Lancer was now predicted to become the mainstay of nuclear defense for the country, Loring was deemed unnecessary for nuclear weapons stationing.[31] That same year, fears began to surface that Loring would be an on the list of the 1988 Base Realignment and Closure Commission. As a result, the community began to rally around the base, which at the time included 3,800 military personnel, 1,000 civilian employees, generated an $80 million payroll the previous year, and was the subject of $34 million in construction services.[32]

In 1981, Loring's bombers were placed on alert after Soviet submarines were spotted off the coast of the region.[33] The base was briefly mentioned in the 1983 movie WarGames, although the film erroneously listed Loring as being home to the 43rd Bombardment Wing.[34] In 1982, the base was hit by two earthquakes, which damaged the base hospital and caused cracks to appear on the walls of the control tower.[35][36]

The 5th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron based at Minot AFB in North Dakota maintained a detachment of three F-15 Eagles at Loring. When the 5th was inactivated in 1987, F-4 Phantom II's from the Minnesota Air National Guard's 148th Fighter-Interceptor Group's 179th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron sent a detachment to Loring. After the detachment left, the Massachusetts Air National Guard's 102nd Fighter Interceptor Wing's 101st Fighter-Interceptor Squadron deployed F-15s to the base, the same ones that were part of the 5th.[37] A second north-south runway, one that had been in the Loring's original plans, was created on Taxiway J as a "pre-launch survivability" runway.[1][38] This made Loring one of three SAC bases with two runways.[8]

In 1989, it was proposed to list Loring on the Environmental Protection Agency's National Priorities List. This was due to the presence of waste oil, fuel, solvents, and pesticides in the soil. Additionally, the burning of waste also created problems, in addition to the use of landfills in old gravel pits on site. The fire training area also needed clean up, as materials were burned until 1974 on that site. Loring was officially added to the list in February 1990.[39]

During Operation Desert Storm, Loring's tankers were responsible for refueling aircraft transiting the Atlantic. It was also used as a stopover for aircraft travelling to the Persian Gulf region due to its vital position. The base was also vital because it allowed planes to be maintained, planes which sometimes would be unable to reach their destination without maintenance. Between 2 August 1990 and 10 May 1991, more than 1,700 aircraft transiting between America and the Persian Gulf region landed at Loring. These included the C-141 Starlifter, C-5 Galaxy, C-130 Hercules, C-21A, A-4 Skyhawk, A-10 Thunderbolt II, Boeing 707, F-16 Fighting Falcon, F/A-18 Hornet, F-111 Aardvark, P-3 Orion, TR-1A Dragonlady, U-2 Dragonlady, B-52 Stratofortress, KC-10 Extender, KC-135 Stratotanker, E-3A Sentry, EA-6B Mercury, and E-8A Joint Stars aircraft.[8]

UFO sighting

During the fall of 1975, the base was the location of unidentified flying object sightings. During the night of 27 October, an unidentified object was spotted hovering near the secure weapons area (the former Caribou AFS). Around 1945 hrs, a member of the 42nd Security Police Squadron spotted an apparent aircraft over the northern perimeter of Loring, at a low altitude. A later teletype message to the National Military Command Center in Washington, D.C., stated: "The A/C [aircraft] definitely penetrated the LAFB [Loring Air Force Base] northern perimeter and on one occasion was within 300 yards (270 m) of the munitions storage area perimeter." In the control tower, a member of the 2192nd Communications Squadron was on duty, when he picked up the craft on radar, nearing the base. After trying to contact the unidentified aircraft to warn it that it was approaching a restricted area, the aircraft entered the airspace over the nuclear weapons storage area and hovered over it at an altitude of 300 feet (91 m), later lowering to 150 feet (46 m). Commander of the 42d Bombardment Wing, Colonel Robert E. Chapman[N 1] arrived 15 minutes later at the weapons storage area and police units were ordered in as well. At this time, he also declared a Security Option 3.[42]

At 2045 hrs, another person on duty in the control tower received a call to track the mysterious craft on radar. For the next 40 minutes, it was observed circling around the weapons storage area, when it suddenly vanished, as though it had landed or dropped below the radar. Witnesses later observed it flying away towards Grand Falls, New Brunswick, twelve miles to the east. Messages were sent to the National Military Command Center, the Air Force Chief of Staff, and Strategic Air Command headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base. The base continued to remain on a high state of alert until the following morning, as efforts to identify the unidentified aircraft through the Maine State Police, local police departments, and the Houlton Federal Aviation Administration office remained elusive.[42]

The next night at 1945 hrs, a craft similar to the one the night before approached the base. In addition to being tracked on radar, it hovered around the area for 30 minutes, with characteristics of movement similar to a helicopter. Additionally, it hovered above the weapons storage area at the same altitude as the night before. At this time, possibly another object (it is unclear if it was the same one as the over the weapons storage area, but it is possible) was spotted over the flightline. The cigar-shaped object was described as hovering in mid-air, jerking around, and turning on and off its lights once. During the blackout, it traveled from the flightline, to the northern end of the runway. According to one service member, the object was chased, and eventually discovered to be hovering five feet off the ground. During this time, it was determined that the object was four car lengths long.[42]

Once again, the object was tracked on radar, taking off towards New Brunswick. Teletype messages were again sent to higher commands, with no explanation being found. One teletype sent on November from Loring's Office of Special Investigations detachment to the National Military Command Center and OSI headquarters reported another, "unidentified helicopter sighted at low level over Loring AFB" over the past two nights (31 October – 1 November). It also referred to the intruder as an "unknown entity." Additionally, Captain Richard R. Fuhs an Operations Officer in the 42nd Security Police Squadron (SPS) stated, "... advised that there had been three verified sightings of an unidentified A/C [aircraft] flying at low level over and in the vicinity of LAFB" during this period. An initial sighting was made by a member of the 42nd, who was on duty at 23:14 hours Another member spotted the object near the East Gate, going from east to west.[42]

BRAC 1991 and closure

In 1991, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, upon the recommendation of Secretary of the Air Force Donald B. Rice, identified Loring and five other SAC bases for closure through the BRAC Commission. The commission recommended that the 42d Bomb Wing be disestablished, and the B-52Gs transferred to the 410th Bomb Wing at K.I. Sawyer AFB near Marquette, Michigan. The KC-135 aircraft were realigned to USAF Reserve and other active units.[43]

The justification for the closure of Loring was that the Air Force had six more strategic bases than were needed to support the number of bomber and tanker aircraft in the Defense Department's Structure Plan. The base was evaluated against eight selection criteria and a large number of subelements specific to Air Force bases and missions. Even though Loring was in good condition and had strong community support, it ranked low in the criteria when compared to twenty other bases in the strategic category. One of the things that hurt Loring was its limited peacetime value as a tanker base, as well as its distance from bombing ranges. The commission did note that the facilities at Loring were above average, and the cost to close Loring would be low, the latter of which contributed to its closure.[43]

The commission also projected an impact on the future of the community; 22,000 people were projected to leave the region with 9,900 direct and indirect jobs affected, and a loss of over $92 million of regional income. This was in contrast to a regional population of over 49,100, available jobs of 33,320, and an annual income of $755 million. The net savings by the end of 1997 from closing the base was $182 million, or about $61.8 million annually.[43]

As the Cold War ended, so did the mission of SAC, and it was disestablished on 1 June 1992. The last B-52 departed Loring in November 1993, and ceremonies were held in February 1994 to celebrate the end of the flying mission. The following month saw the last KC-135 depart and after 41 years, Loring AFB officially closed on 30 September 1994.[1][43]

Accidents and incidents

On 22 November 1958, a B-47B Stratojet crashed while taking off from Loring, killing all four crewmembers on board. The plane belonged to a unit at McCoy Air Force Base in Orlando, Florida. The plane was described as having reached two-thirds of the way down the runway, when it veered sharply to the right, eventually crashing 400 feet north of the runway.[44] On 25 November 1958, a KC-135 Stratotanker of the 42d Air Refueling Squadron crashed on takeoff roughly in the same area as the B-47 three days before. Two crewmembers were thrown to safety by the impact of the crash. The Air Force stated that after a four-hour mission, the crewmembers were practicing taking off and landing on the runway.[45][46] On 18 November 1960, a KC-135 crashed upon landing at Loring, killing one and injuring sixteen others. The plane landed after a six-and-a-half-hour training mission, veered off to the left of the runway, and skidded three thousand feet while on fire. Surviving crewmembers were able to use the emergency chutes to evacuate the plane safely.[47][48] On 9 May 1962, six crewmembers of a KC-135 were killed when their plane crashed during takeoff into a surrounding marsh, about fifteen hundred feet north of the runway.[49][50] On 4 January 1965, four crewmembers were killed three miles north of Loring when their KC-135 crashed into the ground after takeoff.[51][52] On 5 September 1969, a B-52 Stratofortress crashed approximately three miles north of the runway after taking off. Seven men were killed, including six crewmembers, during a Minimum Interval Takeoff drill. On 4 October 1989 a KC-135 crash killed all 4 crewmembers. The jet, which crashed about 2.4 miles off the TransCanada Highway in New Brunswick, was attempting to land at Loring.[53][54][55]

Loring also had its share of incidents that did not result in fatalities over the years. On 6 March 1955, a B-36 Peacemaker crashed and burned in a snowbank at Loring. All crewmembers were able to escape unharmed.[56] On 26 June 1958, a B-52D (55‑0102) burned on the ground at Loring and was destroyed.[54][57] On 25 May 1969, a KC-135A (56–3602) broke in two after aborting takeoff. The cause was a frozen water injection surge tube.[58] On 19 July 1970, a B-52G (58‑0208) also caught on fire and was destroyed on the ground.[54][59]

Base culture and civilian life

Families at the base were able to take advantage of many of the opportunities that the facility provided for them, as life at Loring was not all military-related. Although Loring was constructed with support facilities including a hospital, chapel, and schools, other forms of civilian life were added over the years as well.[5]

Education

Younger students on the base attended Damon Elementary School. Kindergarten-age children would attend school in either morning or afternoon sessions, and the older students were given the standard fare of lunch offerings. Damon's educators were rated highly in the state. Students in grades 9 through twelve attended the nearby Limestone High School.[5]

To those who were no longer in secondary education, there were opportunities as well. The Northern Maine Vocational Technical Institute offered courses that would help students with introductory college-level classes. Husson College offered credits to those working to earn an associate's or baccalaureate degree in business. The nearby University of Maine at Presque Isle offered classes in the social and behavioral sciences, as well as humanities and liberal studies. Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University offered a bachelor's degree in professional aeronautics. Credits earned through these programs counted as "on campus" or "residential credit" to those who were enrolled in them. Additionally, day, evening, and night classes were offered in nearby Caribou and Presque Isle.[5]

For those who wanted to earn a graduate degree, the University of Denver offered a twelve course program for those wanting to earn a Master of Science degree in systems management. Emery-Riddle also offered three graduate degrees, including the Master of Aeronautical Science. The University of Maine at Presque Isle also offered a Master of Public Administration as well.[5]

The base's Education Center also provided testing service for those interested in taking exams. It provided the CLEP, DANTES Exams, SAT, ACT, the LSAT and GRE exams. The Community College of the Air Force also enrolled active duty personnel in its programs as well. Credits taken there could be transferred to other affiliated Air Force technical institutions, and personnel could qualify for commissioning programs.[5]

Healthcare

The Loring Air Force Base Hospital had two buildings during its operation. The first, Building 3500, which was known as the "Green Monster," was damaged during an earthquake on 9 January 1982.[5] The two earthquakes, which were centered in Miramichi, New Brunswick caused irreparable structural damage to the facility, which led to it being replaced with a sturdier hospital in 1987.[35] The new hospital included a dental clinic and outpatient rooms, in addition to over twenty beds.[60] Internal medicine, optometry, general surgery, pediatrics, mental health, and radiology services were also provided at the base, in addition to the 24-hour emergency support services. Veterinary services were also offered in a separate building to base personnel and their families.[5]

Family services

Military members adjusting to Loring had many facilities available to them. This included the Family Service Center, the Family Services Lending Closet, and the Corey Center.[5]

The base was also served by an independent bank, and included help for many types of financial needs, and an ATM. The Country Federal Credit Union was located right outside the facility, and helped supplement the bank itself.[5]

Shopping at Loring could be completed at the Maine Exchange Shopping Mall, which was designed to be a one-stop shop for the shopping needs of the residents. Goods could also be purchased at the base commissary as well, which included a Class VI store.[5]

Loring also was built with a non-denominational chapel, which helped to welcome new members onto the base. Services were offered to those of the Roman Catholic, Protestant denominations, and Judaic faiths. Members of the chapel also provided food for those who ate in Loring's dining hall, and helped to share the word of God to those who were believers.[5]

The base also came with its own newspaper, named Limelite. The on-base newspaper helped to provide readers with information on the USAF and Strategic Air Command, as well as information on the events happening around the facility.[5]

The main dining hall on base was named Dahlgren Hall, after Maine native Edward Dahlgren, who was a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions in World War II.[5]

Leisure activities

When it came to leisure, the area surrounding Loring offered many options. Many recreation areas and campgrounds were located in and around the base region, with some being as far as two hundred miles away. The Morale Welfare and Recreation center offered equipment for these outings, including fishbait and tackle, as well as boat rentals. Loring's bowling center was twenty-two lanes, and one of the most modern in the area. Finally, the base library loaned books to both residents and students alike.[5]

A small downhill ski area provided recreation for personnel and their dependents, operating on the base from the early 1960s until Loring's closure in 1994.[61] This ski chalet also included a lighted skating rink and could be used to host events in the area. The base also offered trips to regional ski resorts periodically, and cross country skiing was offered at the local golf course.[5]

The base also contained a Noncommissioned Officers Club and an Officers Club. The Noncommissioned Officers Club, or Club 42 as it was known, allowed in all military members and civilians up the GS-7. Many varieties of food were also offered there, and it could be used for live entertainment, in addition to the booking of parties. As the Visiting Officers Quarters and the Unaccompanied Officers Quarters were nearby, the club was also a convenient stopover for transient officers as well.[5]

Current status

Loring AFB was set to close as a result of the 1991 Base Realignment and Closure Commission, officially closing on 30 September 1994. Immediately, Limestone was decimated. The population of Limestone dropped 76%, from 10,000 to 2,000, in the six years following the base's closure. Regional economic activity was severely lowered, as 19% of the local economy was related to Loring Air Force Base.[62]

One of the more immediate ideas for redevelopment of the base was to turn it into a federal prison, something which had been done previously at the former Carswell AFB in Texas when the Federal Medical Center, Carswell was opened on its grounds. Many other former Air Force facilities have had prisons opened up on their grounds as well. From the outset, there was some reluctance in the town about turning it into creating a prison culture in Limestone, but this was lessened once the government decided that it did not want to build a federal prison on the grounds of the former air base.[62]

In 1998, the former base was considered for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, as previous studies had found that 88 buildings were eligible for inclusion on the list, including the base's arch hangar.[1][38]

In 1997 the rock band Phish held a three day concert dubbed The Great Went, taking place on August 16 and 17. The world's largest fire truck hosed down thousands of fans as they arrived Saturday morning, and on Sunday morning, approximately 1,100 people posed nude as part of a fifty-state tour by photographer Spencer Tunick. Phish was the only band that played the main stage, performing seven sets of music over two nights, including a late night disco set at 2:30 AM featuring all four members on keyboards. The Bangor Symphony Orchestra performed Debussy and Stravinsky during the afternoon of the second day, accompanied by a glider pilot who soared above the audience. 75,000 people attended, making the event Phish's largest concert up to that point, and the top-grossing rock concert in the United States in the summer of 1997. Fans camped out onsite in tents and RVs, making Limestone the largest city in Maine over the weekend.[63]

Phish again staged a weekendlong concert, this time called Lemonwheel, on August 15 and 16, 1998. 60,000 people attended[64] creating a community of fans that, again, made Limestone one of the largest cities in Maine over the weekend.

The Loring Development Authority created the Loring Commerce Centre on 9,472-acre (38.33 km2) of the site. It was marketed as an "excellent solution for your business real estate needs at a very reasonable cost."[65] Bigelow Aerospace maintains a call center at Loring. In addition to the Sitel site, other call centers exist on the former base, as well as food processing, forestry operations, light manufacturing, and aviation services. The military has made a return to Loring over the years through the Defense Finance and Accounting Service Limestone office, a major component of the Defense Finance and Accounting Service. The 2005 Base Realignment and Closure Commission consolidated DFAS' 26 offices into 5, with Loring being one of the consolidation points. This facility is located in the old base hospital.[66]

Cleanup continued at the base, including the removal of hazardous materials, which prevented further waste from entering the nearby Greenlaw Brook, as it received drainage from the flightline and nose dock areas.[39]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1970 | 6,266 | — | |

| 1980 | 6,572 | 4.9% | |

| 1990 | 7,829 | 19.1% | |

| 2000 | 225 | −97.1% | |

| source:[67][68][69] | |||

During the 1970s, the population of the base declined due to the possible closure of the base and the draw down in personnel from the Vietnam War. In 1972, the base's population was around 12,000, while in 1975 the population was 10,758. In 1978, 9,233 persons resided on the base, which declined to 8,116 the next year.[70]

As of the census[71] of 2000, there were 225 people, 82 households, and 57 families residing on the former base. The population density was 27.4/mi² (10.6/km²). There were 355 housing units at an average density of 43.2/mi² (16.7/km²). The racial makeup of the base was 81.33% White, 10.22% African American, 2.22% Asian, 5.33% from other races, and 0.89% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.78% of the population.[68]

See also

- Eastern Air Defense Force (Air Defense Command)

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Earth Tech, Inc. (1994). "Loring Air Force Base" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey. Historic American Engineering Record. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Written Historical and Descriptive Data Photographs" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ "LORING AIR FORCE BASE, DOUBLE CANTILEVER HANGAR (Loring Air Force Base, Building 8280)" (PDF). Limestone, Maine: Historic American Engineering Record. 1994.

- ↑ "Loring Commerce Centre". Loring Commerce Centre. 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Squadrons and Services". Loring Military Heritage Center. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "42nd Air Base Wing". 42nd Air Base Wing. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ "Air Force Reactivates 69th Bomb Squadron at Minot". Minot Air Force Base: Aero-news.net. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "SAC Bases: Loring Air Force Base". Strategic-air-command.com. 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Groening, Tom (3 July 2012). "Bangor Natural Gas parent buys rights to Searsport-to-Loring pipeline". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ↑ "Cold War Infrastructure for Strategic Air Command: The Bomber Mission" (PDF). Langley Air Force Base, Virginia: Headquarters, Air Combat Command. November 1999. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p. 244.

- ↑ "Steam-Heated Runway Melts 10 Feet of Snow". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 108 no. 4. Hearst Magazines. October 1957. p. 112. ISSN 0032-4558.

- ↑ "Belly-Landing Atom Bomber Flown to Kelly". Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Makar, Michael (July 2006). "Green Pine System – Loring Air Force Base, Maine". All-hazards.com. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "42 AIR BASE WING (AETC)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. 30 November 2007. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "27TH FIGHTER SQUADRON". Langley Air Force Base: Air Force Research Historical Agency. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "53 WING (ACC)". Eglin Air Force Base: Air Force Research Historical Agency. 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Loring Air Force Base, Weapons Storage Area, Northeastern corner of the base at northern end of Maine Road, Limestone vicinity, Aroostook County, ME. On file with The Library of Congress" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Nike Missile Loring Defense Area". The Military Standard. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 42d Bombardment Wing (1959). Operation Headstart (Film reel). Loring Air Force Base, Maine: United States Air Force.

- ↑ "The Air Force versus Hollywood". George Washington University. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ "SAC AIRBORNE ALERT". National Museum of the United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Nixon reports progress towards "lasting peace"". Lewiston Daily Sun. Associated Press. 4 July 1974. p. 1.

- ↑ Spruce, Chris (4 July 1974). "President addresses nation from Loring". Bangor Daily News. p. 1. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Peace Cause Advanced". Bangor Daily News. 4 July 1974. p. 1.

- ↑ "Base Closings: Everyone Wins". The New York Times. 10 October 1988. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ "Northern Maine needs the Air Force". The Telegraph. 25 July 1981. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Bayly, Julia (21 July 2013). "Fort Kent brothers recall years spent keeping planes flying at Loring". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "Mackay 1980–1989 Recipients". National Aeronautic Association. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ White, J. Terry. "Remarkable Airmanship". J. Terry White. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ Halloran, Richard (16 May 1988). "3 nuclear storage depots to close as B-52 missions change". New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Gold, Allan (18 October 1988). "Loring Journal; rallying round an air base in northern Maine". New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ "B-52's in Maine placed on alert after Soviet subs are detected". New York Times. Associated Press. 11 March 1981. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Matthew Broderick, Dabney Coleman, John Wood, and Ally Sheedy (1983). WarGames (Film). United States: United Artists.

- 1 2 Natural Resources Canada. "Important Canadian Earthquakes". Earthquakes Canada. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ Spencer, C.W. (1983). "Earthquakes in the United States, January March 1982 – USGS" (PDF). United States Geological Service. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ Sund, Debra (21 October 1987). "Loring fighters replaced by newer aircraft". Bangor Daily News. p. 9.

- 1 2 Sund, Debra (22 June 1998). "Group hopes to preserve Cold War icon". Bangor Daily News. p. A1.

- 1 2 "LORING AIR FORCE BASE". Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ "BRIGADIER GENERAL ROBERT E. CHAPMAN". United States Air Force. 1981. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ "UFOs Intrude into SAC Base Weapons Areas". Nicap.org. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Greenwood, Lawrence Fawcett, Barry J. (1984). Clear intent: the government coverup of the UFO experience. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-136649-7.

- 1 2 3 4 "Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission, 1991 Report to the President" (PDF). Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ "Bomber Crashes; 4 Aboard". Limestone, Maine: The Miami News. 22 November 1958. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Tanker Plane Falls, Burns; 5 Lose Lives". Limestone, Maine: Spokane Daily Chronicle. 25 November 1958. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Tanker Plane Crash Kills 1". Limestone, Maine: The Portsmouth Times. 18 November 1960. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Six Killed in Air Force Plane Crash". Limestone, Maine: The Dispatch. 9 May 1962. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Air Tanker Crashes, Killing 4". The Miami News. 5 January 1965. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "7 Killed in Bomber Crash". The Evening Independent. Limestone, Maine. 5 September 1969. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 "B-52 Stratofortress Draft Listing". Ejection-history.org.uk. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 48302". Aviation Safety Network. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "11 Flyers Escape As B-36 Crashes, Burns in Maine". Limestone, Maine: Hartford Courant. 7 March 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 48319". Aviation Safety Network. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 48291". Aviation Safety Network. 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Scaled-down hospital plan urged at Loring". Bangor Daily News. 1 October 1984. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ "Loring AFB Ski Area". New England Lost Ski Areas Project. 16 October 2004. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- 1 2 Watson, Bruce (19 August 2010). "A Maine Town's Long Recovery After Losing Loring AFB". AOL.com. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ↑ http://www.phish.net/faq/greatwent.html

- ↑ "Phish Fest Nets $81,000 In Drugs; 1,200 Arrests". SonicNet News. sonicnet.com. 1998-09-02. Archived from the original on April 30, 2005. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ↑ "Loring Commerce Centre". Loring Commerce Centre. 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "The Defense Finance and Accounting Service Limestone Fact Sheet" (PDF). Defense Finance and Accounting Service. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ "Loring AFB Census Designated Place, ME". place.mar.cx. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Units: 1980 to 2000; and Area Measurements and Density: 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 18. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ "U.S. Gazetteer: 2010, 2000, and 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Higgins, A. Jay (30 January 1981). "Loring census down 27 percent since 1972". Bangor Daily News. p. 1. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size (1988). Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0160022606.

- Maurer, Maurer (1961). Air Force Combat Units of World War II (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0912799021.

- Mueller, Robert (1989). Volume 1: Active Air Force Bases Within the United States of America on 17 September 1982 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0160022614.

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1989). Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories 1947–1977 (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0912799129.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Loring Air Force Base. |

- The Loring Remembers Project – Index of those who served at Loring AFB

- Loring Commerce Centre

- LoringAirForceBase.com

- Photos of Loring

- 42nd Air Base Wing Official Page

- Loring Military Heritage Center

- Loring Remembers Picasa group, with images of the base

- Information on the alert area

- Airfield data study

- Study of the base

- Official government report on the UFO sighting

- Possible socioeconomic effects of the base's closure

- 42nd AMS & Flightline Photos