Frank Pakenham, 7th Earl of Longford

| The Right Honourable The Earl of Longford KG PC | |

|---|---|

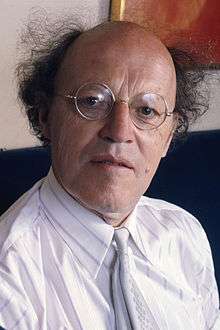

Longford at Allan Warren's studio in London in 1974 | |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

|

In office 17 April 1947 – 31 May 1948 | |

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee |

| Preceded by | John Hynd |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Dalton |

| First Lord of the Admiralty | |

|

In office 24 May 1951 – 13 October 1951 | |

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Hall |

| Succeeded by | James Thomas |

| Leader of the House of Lords Lord Privy Seal | |

|

In office 18 October 1964 – 16 January 1968 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | The Lord Carrington |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Shackleton |

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | |

|

In office 23 December 1965 – 6 April 1966 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Anthony Greenwood |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Lee |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 December 1905 |

| Died | 3 August 2001 (aged 95) |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Harman (m. 1931) |

| Alma mater | New College, Oxford |

Francis Aungier Pakenham, 7th Earl of Longford, 1st Baron Pakenham, KG, PC (5 December 1905 – 3 August 2001), known to his family as Frank Longford and styled Lord Pakenham from 1945 to 1961, was a British politician and social reformer. A member of the Labour Party, he was one of its longest serving politicians. He held cabinet positions on several occasions between 1947 and 1968. Longford was politically active up until his death in 2001. A member of an old, landed Anglo-Irish family, he was one of the few aristocratic hereditary peers to have ever served in senior capacity within a Labour government.

Lord Longford was famed for championing social outcasts and unpopular causes.[1] He is especially notable for his lifelong advocacy of penal reform. Longford visited prisons on a regular basis for nearly 70 years until his death. He advocated for rehabilitation programmes and helped create the modern British parole system in the 1960s following the abolition of the death penalty. His ultimately unsuccessful campaign for the release of Moors murderer Myra Hindley attracted much media and public controversy.

For his tireless work, the Longford Prize is named after him. It is awarded annually during the Longford Lecture and recognises excellence in the world of prison and social reform.

As a devout Christian determined to translate faith into action, he was known for his bombastic style and his eccentricity.[2] Although a shrewd and influential politician, he was also widely unpopular among Labour leaders, particularly for his lack of ministerial ability, and was moved from cabinet post to cabinet post, never serving more than two years at any one ministry. Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson famously stated that Longford had the mental capacity of a 12-year-old.[3]

In 1972, he was made a Knight of the Garter. In the same year, he was appointed to head the group charged with investigating the effects of pornography on society which published the controversial Pornography Report. He became known as a campaigner against pornography and held the view that it was degrading – to its users and to those who worked in the trade, especially women.[4] Longford was also an outspoken critic of the British press and once said it was "trembling on the brink of obscenity."[5]

Lord Longford was politically instrumental in decriminalising homosexuality in the United Kingdom, but later became a staunch opponent of homosexuality, referring to it as "nauseating", "utterly wrongful" and that gay people were "handicapped". He continued to oppose any gay rights legislation, including the equalisation of the age of consent, and also supported the passage of Section 28.[6]

Background and education

Born into an Anglo-Irish aristocratic family, he was the second son of Thomas Pakenham, 5th Earl of Longford in the Peerage of Ireland. He was educated at Eton College and New College, Oxford, where as an undergraduate he was a member of the Bullingdon Club. Despite having failed to be awarded a scholarship, he graduated with a first-class honours degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics and became a don at Christ Church. At Oxford he met his wife, Elizabeth Harman, an undergraduate at Lady Margaret Hall.

Political career

After a disastrous spell at stockbroking with Buckmaster & Moore, in 1931 the 25-year-old Pakenham joined the Conservative Research Department where he developed education policy for the Conservatives. Elizabeth persuaded him to become a socialist.[7] They were married on 3 November 1931 and had eight children. In 1940, only a few months after the onset of the Second World War, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was invalided out of the armed forces.[3] The same year, he became a Roman Catholic. His wife was initially dismayed by this, as she had been brought up a Unitarian and associated the Church of Rome with reactionary politics, but in 1946 she joined the same church.[8]

Pakenham embarked on a political career. In October 1945, he was created Baron Pakenham, of Cowley in the City of Oxford, in the Peerage of the United Kingdom,[9] by the Labour government of Clement Attlee, and took his seat in the House of Lords as one of the few Labour peers. He was immediately appointed a Lord-in-Waiting by Attlee. In 1947, he was appointed deputy Foreign Secretary, outside the cabinet, with special responsibility for the British zone in occupied Germany. He made headlines by telling German audiences that the British people forgave them for what had happened in the war, and was later credited by the first West German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, with being among his country's founding fathers. In May 1948, he was moved to the lower-profile role of Minister of Civil Aviation and was sworn onto the Privy Council in June of that year. He continued in this post until May 1951. From May until the fall of the administration in October 1951, he was First Lord of the Admiralty.

In 1961, Pakenham inherited from his brother the earldom of Longford in the Peerage of Ireland and from then onward was generally known to the public as Lord Longford. When Labour returned to power in October 1964 under Harold Wilson, Longford was appointed Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords,[10] despite the fact that Wilson had little respect for him and once remarked that he had the mental age of 12.[3] In December 1965 he became Secretary of State for the Colonies, continuing as Leader of the House of Lords. After only four months at the Colonial Office, he was removed from the post for failing to master his brief, and again became Lord Privy Seal in April 1966. Wilson often talked about sacking Longford from his government, which is believed to have led to Longford's resignation as Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords in January 1968.[3] In 1972 he was created a Knight of the Garter.[11]

Penal reform

Longford began visiting prisoners in the 1930s when he was a city councillor in Oxford and continued to do so every week, all around the country, until shortly before his death in 2001. Among the thousands he befriended and helped were a small number of individuals who had committed the most notorious crimes, including child murderer Myra Hindley.

In 1956, he set up New Bridge Foundation, an organisation that aimed to help prisoners stay in touch with society and integrate them back into it.[12][13]

New Bridge set up Inside Time in 1990, the only national newspaper for the UK's prison population. As of 2014, novelist and journalist Rachel Billington, Longford's daughter, worked at the title one day a week.[14][15] He organised many debates on prison reform in the House of Lords from the 1950s onwards and in 1963 he chaired the commission whose report led to the establishment of the parole system in 1965.

Longford was a leading figure in the Nationwide Festival of Light of 1971, protesting against the commercial exploitation of sex and violence, and advocating the teaching of Christ as the key to recovering moral stability in the nation. His anti-pornography campaigning made him the subject of derision and he was labeled by the press as Lord Porn when he and former prison doctor Christine Temple-Saville set out on a wide-ranging tour of sex industry establishments in the early 1970s to compile a self-funded report. The press made much of his visits to strip clubs in Copenhagen.

Myra Hindley

He gained a reputation for eccentricity, becoming known for his efforts to rehabilitate offenders and in particular campaigning for the parole and release from prison of the Moors murderer Myra Hindley, who had been jailed for life along with Ian Brady in 1966 for the Moors Murders.

Longford's support for Hindley led to the soubriquet Lord Wrongford from the tabloid press, which largely opposed Hindley being released from prison. It also coincided with Longford's contact with Hindley becoming public knowledge in 1972, and allegations of hypocrisy were frequently made against him. In 1977, 11 years after Hindley was convicted of two murders and being an accessory to a third murder, Longford appeared on television and spoke openly of his belief that Hindley should now be considered for parole as she had shown clear signs of progress in prison and now served long enough for the Parole Board to assess her suitability for release from prison. He also supported Hindley's claims that her role in the Moors Murders was merely that of an accomplice, and that she had only taken part due to Brady's abuse and threats. These claims were aired in the inaugural episode of Brass Tacks, which featured arguments for and against Hindley being considered for parole. Ann West, the mother of Lesley Ann Downey, spoke of her determination that Hindley should never be released, and openly told viewers that she would kill Hindley if she ever was released.

In 1985, he condemned the Parole Board's decision not to consider Hindley's release for another five years as "barbaric", and his campaign for Hindley continued even after she admitted to two more murders in 1986. This development further strengthened media and public opinion that any reports of progress by Hindley in prison were nothing more than a ploy to boost her chances of gaining release from prison.

In 1990, Home Secretary David Waddington ruled that "life should mean life" for Hindley, who had been told by earlier Home Secretaries and High Court judges that she would have to serve a minimum of 25 and then 30 years before being considered for parole. Hindley was not informed of the decision until December 1994, and Longford later expressed his "disgust" at this ruling. The next three Home Secretaries all agreed with Waddington's ruling. Hindley appealed against her whole life tariff in the High Court in December 1997, November 1998 and March 2000, but each appeal was rejected. Longford maintained that she was a changed woman who was no longer a threat to society, and had qualified for parole. He regularly commented, along with several other Hindley supporters, that she was a "political prisoner" who was being kept in prison for votes, to serve the interests of a succession of Home Secretaries and their respective governments.

In March 1996, Longford backed up Hindley's claim in an Oxford University magazine that she was still in prison so that the Conservative government - trailing in the opinion polls since the autumn of 1992 - would win more votes. This claim was met with anger by the mothers of two of the Moors Murders victims, including Ann West, who remained at the centre of the campaign to ensure that Hindley was never released, and once again vowed to kill Hindley if she was set free.[16] Longford regularly condemned the media for "manipulating" West and feeding her desire for revenge, being particularly critical of The Sun newspaper for its "exploitation" of West — referring to her numerous television and newspaper interviews in which she argued against any suggestion of Hindley ever being paroled, often threatening to kill her if she was ever set free.[17] In 1986, Longford reportedly told West that unless she forgave Hindley and Brady, she would not go to Heaven when she died. He also commented that he was "tremendously sorry for her, but letting her decide Myra's fate would be ludicrous".[18]

Hindley died in November 2002, having never been paroled.

The story of Longford's campaign to free Hindley was told in the Channel 4 film Longford in 2006. Longford was played by Jim Broadbent (who won a BAFTA for his role) and Hindley was played by Samantha Morton.

Opposition to homosexuality

In 1956, Longford launched the first Parliamentary debate in support of the Wolfenden Report, which recommended the decriminalisation of homosexuality. He had been a staunch public supporter of Lord Montagu and his lover Peter Wildeblood after the two were jailed for breaking anti-gay laws in the early 1950s, and visited them regularly in prison.[19]

In his later years, however, he became a staunch opponent of gay rights. In the 1960s, despite taking a lead in the decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales, he stated that homosexuality was "nauseating" and that, regardless of any change in the law, it was "utterly wrongful".[20]

In the mid-1980s, Longford was a vocal supporter of the introduction of Section 28 by Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government and, during the Parliamentary debates, he famously stated his opinion that homosexuals are "handicapped people".[21] Section 28 became law in 1988, but Longford continued to support it and fought against its repeal when the new Labour government came to power in 1997. It was repealed in 2003.

Longford also opposed the Labour government's plans to equalise the age of consent for gay men (at that time 18) with that of heterosexual men (16), and in a 1998 House of Lords debate he remarked that:

...if someone seduced my daughter, it would be damaging and horrifying but not fatal. She would recover, marry and have lots of children... On the other hand, if some elderly, or not so elderly, schoolmaster seduced one of my sons and taught him to be a homosexual, he would ruin him for life. That is the fundamental distinction.[22]

The age of consent for gay men was equalised at 16 in 2000.

Longford's highly publicised condemnation of homosexuality in the late 1980s made him a regular target of the comedian Julian Clary, who often satirised him in his stage shows and television appearances.[23]

House of Lords reforms (1999)

Under the House of Lords Act 1999, the majority of hereditary peers lost the privilege of a seat and right to vote in the House of Lords. However, he was created a life peer as Baron Pakenham of Cowley, of Cowley in the County of Oxfordshire,[24] which allowed him to remain in the Lords. At the age of 93, he became the second-oldest person to be granted a peerage (after Lord Maenan).

Writings

Known for his interest in Irish history, he wrote a number of books on the topic. Peace By Ordeal: An Account from First-Hand Sources of the Negotiation and Signature of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, published in 1935, is arguably his best-known work, which documents the negotiations of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 between Irish and British representatives. His account uses primary sources from the time and is widely recognised as the definitive account of this aspect of Irish history.[25] Longford came to greatly admire Éamon de Valera and was chosen as the co-author of his official biography Éamon de Valera, which was published in 1970, co-written with Thomas P. O'Neill. He campaigned for decades to have the Hugh Lane bequest pictures restored to Dublin, resulting in a compromise agreement in 1959.

Personal life

Longford died in August 2001 at the age of 95 and was cremated at Mortlake Crematorium.[26] He and his wife would have celebrated their 70th wedding anniversary on 3 November. Their marriage produced four sons and four daughters, followed by 26 grandchildren and 18 great-grandchildren.

- 1. Lady Antonia Margaret Caroline Pakenham (b. 27 August 1932), writer; previously married to Hugh Fraser and had six children, was married to the late Harold Pinter until his death

- 2. Thomas Frank Dermot Pakenham, 8th Earl of Longford (b. 14 August 1933), historian; married with issue

- 3. Hon. Patrick Maurice Pakenham (17 April 1937 – 8 June 2005[27]), barrister; married Mary Plummer, three children

- 4. Judith Elizabeth Pakenham (b. 14 August 1940), writer; previously married to Alexander John Kazantzis, two children

- 5. Lady Rachel Mary Pakenham (b. 11 April 1942), writer; married to director Kevin Billington, three children

- 6. Hon. Sir Michael Aidan Pakenham (b. 3 November 1943), diplomat; married to Meta Landreth Doak, two children

- 7. Lady Catherine Rose Pakenham (28 February 1946 – 11 August 1969), journalist; died in a car accident

- 8. Hon. Kevin John Toussaint Pakenham (b. 1 November 1947), banker;[28] married to Claire Hoare, five children (including two from a previous marriage)

His wife, Elizabeth Pakenham, Countess of Longford, died in October 2002 at the age of 96.[29] She was a noted writer, her most famous book being Victoria R.I. (1964), a biography of Queen Victoria, published in the US as Born to Succeed. She also wrote a two-volume biography of the Duke of Wellington, and a volume of memoirs, The Pebbled Shore. She stood for Parliament as Labour candidate for Cheltenham in the 1950 general election.

Peter Stanford provided an example in The Guardian obituary of Lord Longford's deep humanity: In the late 1980s, he was contacted by the solicitor for a young Dutchman, convicted of a drugs offence, sent to Albany prison on the Isle of Wight, suffering from AIDS and cut off by his family. Longford was the only person to visit this dying man, a gesture repeated in countless episodes that never made headlines, but which brought succour and relief.[2]

Prime Minister Tony Blair said of Lord Longford after his death: "He was a great man of passionate integrity and humanity, and a great reformer committed to modernising the law, while also caring deeply for individuals."[5]

See also

The Longford Trust

The Longford Trust celebrates the achievements and continues the work of Lord Longford. It was established in 2002 by friends and admirers to further the goals he pursued, particularly in the field of social and prison reform. Each year the Trust hosts a lecture, part of a series inaugurated in 2002, chaired every year by Jon Snow. It also bestows The Longford Prize to highly commended individuals and organisations in the field of penal reform.

Notes

- ↑ Hoge, Warren (6 August 2001). "Lord Longford, Champion of Eccentric Causes, Dies at 95". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- 1 2 Stanford, Peter. "Obituary: Lord Longford". The Guardian. London.

- 1 2 3 4 Stanford, Peter (6 August 2001). "Lord Longford". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Walker, Andrew (19 October 2006). "The saint and the sinner". BBC.

- 1 2 "Campaigning Lord Longford dies". cnn.com. 3 August 2001.

- ↑ Smith, Anna Marie (1994). New Right Discourse on Race and Sexuality: Britain, 1968-1990. Cambridge University Press. p. 205.

- ↑ "Campaigner Lord Longford dies", BBC News, 3 August 2001. Retrieved on 31 March 2007.

- ↑ Mary Craig, Longford—A Biographical Portrait (Hodder & Stoughton, 1978), pp. 59-61

- ↑ "No. 37305". The London Gazette. 12 October 1945. p. 5026.

- ↑ "Peering at the Catholic lords". Catholic Herald. 18 January 1985.

- ↑ "No. 45349". The London Gazette. 23 April 1971. p. 4083.

- ↑ Peter Stanford "Looking for a Way Out", The Independent, 20 July 2003; retrieved on 31 March 2007.

- ↑ "ABOUT US". New Bridge Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ "Inside Story: Prison media". The Independent. 18 February 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ Billington, Rachel (November 2014). "Month by Month". Inside Time Newspaper.

- ↑ "Hindley votes claim lashed.". thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "They're smiling in heaven". The Sun. London, UK. 22 May 2007.

- ↑ "Why Myra must never be freed; Scots detective who arrested evil Hindley ends 30-year silence". bernardomahoney.com. 23 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008.

- ↑ Stanford, Peter (2003). The Outcast's Outcast : A Biography of Lord Longford. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 512 pp. ISBN 0-7509-3248-1.

- ↑ Galloway, Bruce. Prejudice and Pride: Discrimination Against Gay People in Modern Britain. , Routledge & Keegan Paul Publishing, 1983, (page 85 - Nigel Warner).

- ↑ "Workers' Liberty". workersliberty.org.

- ↑ Stonewall website - Sexual Offences Amendment Bill (1999) - Parliamentary Briefing (page 11)

- ↑ Julian Clary - The Mincing Machine Tour - Virgin Video Media (1989)

- ↑ "No. 55672". The London Gazette. 19 November 1999. p. 12349.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Burke (1985). The Zeal of the Convert : the Life of Erskin Childers. Second Chance Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-933256-53-8.

- ↑ "Mortlake Crematorium" (PDF). On Kew. Spring 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2013.

- ↑ "Obituaries — Patrick Pakenham". The Daily Telegraph. 22 June 2005.

- ↑ "Team: Kevin Pakenham". pakenhampartners.com.

- ↑ Bradford, Sarah (24 October 2002). "The Countess of Longford". The Independent. London. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

Titles from birth to death

- The Hon. Francis Pakenham (1905–1945)

- The Rt Hon. The Lord Pakenham (1945–1948)

- The Rt Hon. The Lord Pakenham, PC (1948–1961)

- The Rt Hon. The Earl of Longford, PC (1961–1971)

- The Rt Hon. The Earl of Longford, KG, PC (1971–2001)

Ancestry

Films about Lord Longford

- Longford (2006): Longford's efforts to obtain parole for Moors murderer Myra Hindley were dramatised in a Channel 4 film with Longford portrayed by Jim Broadbent, Samantha Morton as Myra Hindley, Lindsay Duncan as Lady Longford and Andy Serkis as Ian Brady.

Books about Lord Longford

- Stanford, Peter (2003). The Outcast's Outcast : A Biography of Lord Longford. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. p. 512. ISBN 0-7509-3248-1.

External links

- Longford Trust

- New Bridge Foundation

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Longford

- "Campaigner Lord Longford dies". BBC News article dated Friday, 3 August 2001

- "Lord Longford: Aristocratic moral crusader". BBC News obituary dated Friday, 3 August 2001

- "Tributes to humanist peer". BBC News article dated Friday, 3 August 2001

- Lord Longford. Guardian obituary by Peter Stanford dated Monday, 6 August 2001

- Announcement of his taking the oath for the first time as Lord Pakenham of Cowley, House of Lords Minute of Proceedings, 17 November 1999

- Recognition of his work on the Hugh Lane bequest

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title New government |

Lord-in-Waiting 1945–1946 |

Succeeded by The Lord Chorley |

| Preceded by John Burns Hynd |

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster 1947–1948 |

Succeeded by Hugh Dalton |

| Preceded by The Lord Nathan |

Minister of Civil Aviation 1948–1951 |

Succeeded by The Lord Ogmore |

| Preceded by The Viscount Hall |

First Lord of the Admiralty 1951 |

Succeeded by James Thomas |

| Preceded by The Lord Carrington |

Leader of the House of Lords 1964–1968 |

Succeeded by The Lord Shackleton |

| Preceded by Selwyn Lloyd |

Lord Privy Seal 1964–1965 |

Succeeded by Sir Frank Soskice |

| Preceded by Anthony Greenwood |

Secretary of State for the Colonies 1965–1966 |

Succeeded by Frederick Lee |

| Preceded by Sir Frank Soskice |

Lord Privy Seal 1966–1968 |

Succeeded by The Lord Shackleton |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by The Earl Alexander of Hillsborough |

Leader of the Labour Party in the House of Lords 1964–1968 |

Succeeded by The Lord Shackleton |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| Preceded by Edward Pakenham |

Earl of Longford 1961–2001 |

Succeeded by Thomas Pakenham |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Baron Pakenham 1945–2001 |

Succeeded by Thomas Pakenham |