Long-tailed weasel

| Long-tailed weasel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Subfamily: | Mustelinae |

| Genus: | Mustela |

| Species: | M. frenata |

| Binomial name | |

| Mustela frenata Lichtenstein, 1831 | |

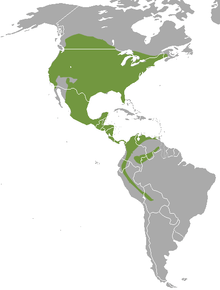

| |

| Long-tailed weasel range | |

The long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata), also known as the bridled weasel or big stoat, is a species of mustelid distributed from southern Canada throughout all the United States and Mexico, southward through all of Central America and into northern South America. It is distinct from the short-tailed weasel, also known as a "stoat", a close relation which originated in Eurasia and crossed into North America some half million years ago.

Evolution

The long-tailed weasel is the product of a process begun 5–7 million years ago, when northern forests were replaced by open grassland, thus prompting an explosive evolution of small, burrowing rodents. The long-tailed weasel's ancestors were larger than the current form, and underwent a reduction in size to exploit the new food source. The long-tailed weasel arose in North America 2 million years ago, shortly before the stoat evolved as its mirror image in Eurasia. The species thrived during the Ice Age, as its small size and long body allowed it to easily operate beneath snow, as well as hunt in burrows. The long-tailed weasel and the stoat remained separated until half a million years ago, when falling sea levels exposed the Bering land bridge, thus allowing the stoat to cross into North America. However, unlike the latter species, the long-tailed weasel never crossed the land bridge, and did not spread into Eurasia.[2]

.jpg)

Description

The long-tailed weasel is one of the larger members of the genus Mustela in North America. There is substantial disagreement both on the upper end of their size and difference in size by sex by source: one indicates a body length of 300–350 mm (12–14 in) and a tail comprising 40–70% of the head and body length. It adds that In most populations, females are 10–15% smaller than males,[3] thus making them about the same size as large male stoats, according to a second source.[4] A third states they range from 11 to 22 inches (280–560 mm) in length, with the tail measuring an additional 3 to 6 inches (80–150 mm). It maintains the long-tailed weasel weighs between 3 and 9 ounces (85-267 g) with males being about twice as large as the females.[5]

The eyes are black in daylight, but glow bright emerald green when caught in a spotlight at night.[6] The dorsal fur is brown in summer, while the underparts are whitish and tinged with yellowish or buffy brown from the chin to the inguinal region. The tail has a distinct black tip. Long-tailed weasels in Florida and the southwestern US may have facial markings of a white or yellowish colour. In northern areas in winter, the long-tailed weasel's fur becomes white, sometimes with yellow tints, but the tail retains its black tip.[3] The long-tailed weasel moults twice annually, once in autumn (October to mid-November) and once in spring (March–April). Each moult takes about 3–4 weeks and is governed by day length and mediated by the pituitary gland. Unlike the stoat, whose soles are thickly furred all year, the long-tailed weasel's soles are naked in summer.[4] The long-tailed weasel has well-developed anal scent glands, which produce a strong and musky odour. Unlike skunks, which spray their musk, the long-tailed weasel drags and rubs its body over surfaces in order to leave the scent,[7] to mark their territory and, when startled or threatened, to discourage predators.[8]

Behaviour

Reproduction and development

The long-tailed weasel mates in July–August, with implantation of the fertilized egg on the uterine wall being delayed until about March. The gestation period lasts 10 months, with actual embryonic development taking place only during the last four weeks of this period, an adaptation to timing births for spring, when small mammals are abundant. Litter size generally consists of 5–8 kits, which are born in April–May. The kits are born partially naked, blind and weighing 3 grams, about the same weight of a hummingbird. The long-tailed weasel's growth rate is rapid, as by the age of three weeks, the kits are well furred, can crawl outside the nest and eat meat. At this time, the kits weigh 21–27 grams. At five weeks of age, the kit's eyes open, and the young become physically active and vocal. Weaning begins at this stage, with the kits emerging from the nest and accompanying the mother in hunting trips a week later. The kits are fully grown by autumn, at which time the family disbands. The females are able to breed at 3–4 months of age, while males become sexually mature at 15–18 months.[7]

Denning and sheltering behaviour

The long-tailed weasel dens in ground burrows, under stumps or beneath rock piles. It usually does not dig its own burrows, but commonly uses abandoned chipmunk holes. The 22–30 cm (8.7–11.8 in) diameter nest chamber is situated around 60 cm (24 in) from the burrow entrance, and is lined with straw and the fur of prey.[7]

Diet

The long-tailed weasel is a fearless and aggressive hunter which may attack animals far larger than itself. When stalking, it waves its head from side to side in order to pick up the scent of its prey. It hunts small prey, such as mice, by rushing at them and kills them with one bite to the head. With large prey, such as rabbits, the long-tailed weasel strikes quickly, taking its prey off guard. It grabs the nearest part of the animal and climbs upon its body, maintaining its hold with its feet. The long-tailed weasel then manoeuvres itself to inflict a lethal bite to the neck.[9]

The long-tailed weasel is an obligate carnivore which prefers its prey to be fresh or alive, eating only the carrion stored within its burrows. Rodents are almost exclusively taken when they are available. Its primary prey consists of mice, rats, squirrels, chipmunks, shrews, moles and rabbits. Occasionally, it may eat small birds, bird eggs, reptiles, amphibians, fish, earthworms and some insects. The species has also been observed to take bats from nursery colonies. It occasionally surplus kills, usually in spring when the kits are being fed, and again in autumn. Some of the surplus kills may be cached, but are usually left uneaten. Kits in captivity eat from ¼–½ of their body weight in 24 hours, while adults eat only one fifth to one third. After killing its prey, the long-tailed weasel laps up the blood, but does not suck it, as is popularly believed. With small prey, also the fur, feathers, flesh and bones are consumed, but only some flesh is eaten from large prey. When stealing eggs, the long-tailed weasel removes each egg from its nest one at a time, then carries it in its mouth to a safe location where it bites off the top and licks out the contents or if they have babies in the den they may hold it in their mouth all the way back to them.[9]

Subspecies

As of 2005,[10] 42 subspecies are recognised.

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridled weasel Mustela f. frenata |

Lichtenstein, 1831 | A large subspecies with a long tail, relatively short black tip and has a black head with conspicuous white markings[11] | Mexico | aequatorialis (Coues, 1877) brasiliensis (Sevastianoff, 1813) |

| Mustela f. affinis | Gray, 1874 | A large, very dark subspecies with very little white marking on the face[12] | costaricensis (J. A. Allen, 1916) macrurus (J. A. Allen, 1912) | |

| Mustela f. agilis | Tschudi, 1844 | macrura (J. A. Allen 1916) | ||

| Black Hills weasel Mustela f. alleni |

Merriam, 1896 | Similar to arizonensis in size and general characters, but with yellower upper parts[13] | Black Hills, South Dakota | |

| Mustela f. altifrontalis | Hall, 1936 | saturata (Miller, 1912) | ||

| Arizona weasel Mustela f. arizonensis |

Mearns, 1891 | Similar to longicauda, but smaller in size[14] | Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountain systems, reaching British Columbia in the Rocky Mountain region | |

| Mustela f. arthuri | Hall, 1927 | |||

| Mustela e. celenda | Hall, 1944 | |||

| Mustela f. aureoventris | Gray, 1864 | affinis (Lönnberg, 1913) jelskii (Taczanowski, 1881) | ||

| Mustela f. boliviensis | Hall, 1938 | |||

| Mustela f. costaricensis | Goldman, 1912 | brasiliensis (Gray, 1874) | ||

| Mustela f. effera | Hall, 1936 | |||

| Chiapas weasel Mustela f. goldmani |

Merriam, 1896 | Similar to frenata in size and general characters, but with a longer tail and hind feet, darker fur and more restricted white markings[15] | Mountains of southeastern Chiapas | |

| Mustela f. gracilis | Brown, 1908 | |||

| Mustela f. helleri | Hall, 1935 | |||

| Mustela f. inyoensis | Hall, 1936 | |||

| Mustela f. latirostra | Hall, 1896 | arizonensis (Grinnell and Swarth, 1913) | ||

| Mustela f. leucoparia | Merriam, 1896 | Similar to frenata, but slightly larger and with more extensive white markings[16] | ||

| Common long-tailed weasel Mustela f. longicauda

|

Bonaparte, 1838 | A large subspecies with a very long tail and short black tip. The upper parts are pale yellowish brown or pale raw amber brown, while the underparts vary in colour from strong buffy yellow to ochraceous orange[17] | Great Plains from Kansas northward | |

| Mustela f. macrophonius | Elliot, 1905 | |||

| Mustela f. munda | Bangs, 1899 | |||

| Mustela f. neomexicanus | Barber and Cockerell, 1898 | |||

| Mustela f. nevadensis | Hall, 1936 | longicauda (Coues, 1891) | ||

| Mustela f. nicaraguae | J. A. Allen, 1916 | |||

| Mustela f. nigriauris | Hall, 1936 | xanthogenys (Gray, 1874) | ||

|

Mustela f. notius |

Bangs, 1899 | |||

| New York weasel Mustela f. noveboracensis

|

Emmons, 1840 | A large subspecies, with a shorter tail than longicauda. The upper parts are rich, dark chocolate brown, while the underparts and upper lip are white and washed with yellowish.[18] | Eastern United States from southern Maine to North Carolina and west to Illinois | fusca (DeKay, 1842) richardsonii (Baird, 1858) |

| Mustela f. occisor | Bangs, 1899 | |||

| Mustela f. olivacea | Howell, 1913 | |||

| Oregon weasel Mustela f. oregonensis |

Merriam, 1896 | Similar to xanthogenys, but larger, darker in colour and has more restricted facial markings[19] | Rogue River Valley, Oregon | |

| Mustela f. oribasus | Bangs, 1899 | |||

| Mustela f. panamensis | Hall, 1932 | |||

| Florida weasel Mustela f. peninsulae

|

Rhoads, 1894 | Equal in size to noveboracensis, but with a skull more similar to that of longicauda. The upper parts are dull chocolate brown, while the underparts are yellowish[20] | Florida Peninsula | |

| Mustela f. perda | Merriam, 1902 | |||

| Mustela f. perotae | Hall, 1936 | |||

| Mustela f. primulina | Jackson, 1913 | |||

| Mustela f. pulchra | Hall, 1936 | |||

| Cascade Mountains weasel Mustela f. saturata |

Merriam, 1896 | Similar to arizonensis, but larger and darker, with an ochraceous belly and distinct spots behind the corners of the mouth[21] | ||

| Mustela f. spadix | Bangs, 1896 | Similar to longicauda, but much darker[22] | ||

| Mustela f. texensis | Hall, 1936 | |||

| Tropical weasel Mustela f. tropicalis

|

Merriam, 1896 | Similar to frenata, but much smaller and darker, with less extensive white facial marking and an orange underbelly[23] | Tropical coast belt of southern Mexico and Guatemala from Vera Cruz southward | frenatus (Coues, 1877) noveboracensis (DeKay, 1840) |

| Washington weasel Mustela f. washingtoni |

Merriam, 1896 | Similar to noveboracensis in size, but with a longer tail and shorter black tip[24] | Washington state | |

| California weasel Mustela f. xanthogenys |

Gray, 1843 | A medium-sized subspecies with a long tail, a face marked with whitish and ochraceous underparts[19] | Sonoran and Transition faunas of California, on both sides of the Sierra Nevada |

References

Notes

- ↑ Reid, F. & Helgen, K. (2008). "Mustela frenata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 29 March 2010. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

- ↑ Macdonald 1992, p. 205

- 1 2 Feldhamer, Thompson & Chapman 2003, p. 651

- 1 2 Merritt & Metinko 1987, p. 280

- ↑ LONG-TAILED WEASEL (Mustela frenata), Description; Northern State University, Aberdeen, South Dakota

- ↑ Schwartz & Schwartz 2001, p. 303

- 1 2 3 Merritt & Metinko 1987, p. 282

- ↑ Long-tailed Weasel. Esf.edu. Retrieved on 2014-05-10.

- 1 2 Schwartz & Schwartz 2001, pp. 306–307

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 26–28

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Merriam 1896, p. 24

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 22–24

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 16–18

- 1 2 Merriam 1896, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Merriam 1896, p. 19

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Merriam 1896, p. 21

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Merriam 1896, pp. 18–19

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mustela frenata. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Mustela frenata |

- Coues, Elliott (1877). "Fur-bearing Animals: A Monograph of North American Mustelidae". Government Printing Office.

- Feldhamer, George A.; Thompson, Bruce Carlyle; Chapman, Joseph A. (2003). "Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and conservation". JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-7416-5.

- Kurtén, Björn (1980). "Pleistocene mammals of North America". Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03733-3.

- Macdonald, David (1992). "The Velvet Claw: A Natural History of the Carnivores". New York: Parkwest. ISBN 0-563-20844-9.

- Merriam, Clinton Hart (1896), Synopsis of the weasels of North America, Washington : Govt. Print. Off.

- Merritt, Joseph Anne; Matinko, Ruth F. (1987), Guide to the mammals of Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh Press, ISBN 0-8229-5393-5

- Schwartz, Charles Walsh; Schwartz, Elizabeth Reeder (2001), The wild mammals of Missouri, University of Missouri Press, ISBN 0-8262-1359-6