Pole star

Pole star or polar star is a name of Polaris in the constellation Ursa Minor, after its property of being the naked-eye star closest to the Earth's north celestial pole. Indeed, the name Polaris, introduced in the 18th century, is shortened from New Latin stella polaris, meaning "pole star". Polaris is also known as Lodestar, Guiding Star, or North Star from its property of remaining in a fixed position throughout the course of the night and its use in celestial navigation. It is a dependable indicator of the direction toward the geographic north pole, although not exact; it is virtually fixed, and its angle of elevation can also be used to determine latitude. The south celestial pole lacks a bright star like Polaris to mark its position. At present, the naked-eye star nearest to the celestial south pole is the faint Sigma Octantis, which is sometimes called the South Star.

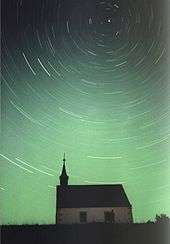

The identity of the pole stars gradually changes over time because the celestial poles exhibit a slow continuous drift through the star field. The primary reason for this is the precession of Earth's rotational axis, which causes its orientation to change over time. Precession causes the celestial poles to trace out circles on the celestial sphere approximately once every 26,000 years, passing close to different stars at different times (with an additional slight shift due to the proper motion of the stars).

In a more general sense, a pole star may be any fixed star close to either celestial pole of any given planetary body.

History

In classical antiquity, Beta Ursae Minoris (Kochab) was closer to the celestial north pole than Alpha Ursae Minoris. While there was no naked-eye star close to the pole, the midpoint between Alpha and Beta Ursae Minoris was reasonably close to the pole, and it appears that the entire constellation of Ursa Minor, in antiquity known as Cynosura (Greek Κυνοσούρα "dog's tail") was used as indicating the northern direction for the purposes of navigation by the Phoenicians.[1] The ancient name of Ursa Minor, anglicized as cynosure, has since itself become a term for "guiding principle" after the constellation's use in navigation.

Alpha Ursae Minoris (Polaris) was described as ἀειφανής "always visible" by Stobaeus in the 5th century, when it was still removed from the celestial pole by about 8°. It was known as scip-steorra ("ship-star") in 10th-century Anglo-Saxon England, reflecting its use in navigation. At around the same time, in the Hindu Puranas, it became personified under the name Dhruva ("immovable, fixed").

In the medieval period, Polaris was also known as stella maris "star of the sea" (from its use for navigation at sea), as in e.g. Bartholomeus Anglicus (d. 1272), in the translation of John Trevisa (1397):

- "by the place of this sterre place and stedes and boundes of the other sterres and of cercles of heven ben knowen: therefore astronomers beholde mooste this sterre. Then this ster is dyscryved of the moste shorte cercle; for he is ferre from the place that we ben in; he hydeth the hugenesse of his quantite for unmevablenes of his place, and he doth cerfifie men moste certenly, that beholde and take hede therof; and therfore he is called stella maris, the sterre of the see, for he ledeth in the see men that saylle and have shyppemannes crafte."[2]

Polaris was associated with Marian veneration from an early time, Our Lady, Star of the Sea being a title of the Blessed Virgin. This tradition goes back to a misreading of Saint Jerome's translation of Eusebius' Onomasticon, De nominibus hebraicis (written ca. 390). Jerome gave stilla maris "drop of the sea" as a (false) Hebrew etymology of the name Maria. This stilla maris was later misread as stella maris; the misreading is also found in the manuscript tradition of Isidore's Etymologiae (7th century);[3] it probably arises in the Carolingian era; a late 9th-century manuscript of Jerome's text still has stilla, not stella,[4] but Paschasius Radbertus, also writing in the 9th century, makes an explicit reference to the "Star of the Sea" metaphor, saying that Mary is the "Star of the Sea" to be followed on the way to Christ, "lest we capsize amid the storm-tossed waves of the sea."[5]

The name stella polaris was coined in the Renaissance, even though at that time it was well recognized that it was several degrees away from the celestial pole; Gemma Frisius in the year 1547 determined this distance as 3°7'.[6] An explicit identification of Mary as stella maris with the North Star (Polaris) becomes evident in the title Cynosura seu Mariana Stella Polaris (i.e. "Cynosure, or the Marian Polar Star"), a collection of Marian poetry published by Nicolaus Lucensis (Niccolo Barsotti de Lucca) in 1655.

Precession of the equinoxes

As of October 2012, Polaris had the declination +89°19′8″ (at epoch J2000 it was +89°15′51.2″). Therefore, it always appears due north in the sky to a precision better than one degree, and the angle it makes with respect to the true horizon (after correcting for refraction and other factors) is equal to the latitude of the observer to better than one degree. The celestial pole will be nearest Polaris in 2100 and will thereafter become more distant.[7]

Due to the precession of the equinoxes (as well as the stars' proper motions), the role of North Star has passed (and will pass) from one star to another in the remote past (and in the remote future). In 3000 BCE, the faint star Thuban in the constellation Draco was the North Star. At magnitude 3.67 (fourth magnitude) it is only one-fifth as bright as Polaris, and today it is invisible in light-polluted urban skies.

During the 1st millennium BCE, β Ursae Minoris was the bright star closest to the celestial pole, but it was never close enough to be taken as marking the pole, and the Greek navigator Pytheas in ca. 320 BCE described the celestial pole as devoid of stars. In the Roman era, the celestial pole was about equally distant from α Ursae Minoris (Cynosura) and β Ursae Minoris (Kochab).

The precession of the equinoxes takes about 25,770 years to complete a cycle. Polaris' mean position (taking account of precession and proper motion) will reach a maximum declination of +89°32'23", which translates to 1657" (or 0.4603°) from the celestial north pole, in February 2102. Its maximum apparent declination (taking account of nutation and aberration) will be +89°32'50.62", which is 1629" (or 0.4526°) from the celestial north pole, on 24 March 2100.[8]

Gamma Cephei (also known as Alrai, situated 45 light-years away) will become closer to the northern celestial pole than Polaris around 3000 CE. Iota Cephei will become the pole star some time around 5200 CE. First-magnitude Deneb will be within 5° of the North Pole in 10,000 CE.

When Polaris becomes the North Star again around 27,800 CE, due to its proper motion it then will be farther away from the pole than it is now, while in 23,600 BCE it was closer to the pole.

Southern pole star (South Star)

Currently, there is no South Star as useful as Polaris. Sigma Octantis is the closest naked-eye star to the south Celestial pole, but at apparent magnitude 5.45 it is barely visible on a clear night, making it unusable for navigational purposes.[9] It is a yellow giant 275 light years from Earth. Its angular separation from the pole is about 1° (as of 2000). The Southern Cross constellation functions as an approximate southern pole constellation, by pointing to where a southern pole star would be.

At the equator, it is possible to see both Polaris and the Southern Cross.[10] [11] The Celestial south pole is moving toward the Southern Cross, which has pointed to the south pole for the last 2000 years or so. As a consequence, the constellation is no longer visible from subtropical northern latitudes, as it was in the time of the ancient Greeks.

Around 200 BCE, the star Beta Hydri was the nearest bright star to the Celestial south pole. Around 2800 BCE, Achernar was only 8 degrees from the south pole.

In the next 7500 years, the south Celestial pole will pass close to the stars Gamma Chamaeleontis (4200 CE), I Carinae, Omega Carinae (5800 CE), Upsilon Carinae, Iota Carinae (Aspidiske, 8100 CE) and Delta Velorum (9200 CE).[12] From the eightieth to the ninetieth centuries, the south Celestial pole will travel through the False Cross. Around 14,000 CE, when Vega is only 4° from the North Pole, Canopus will be only 8° from the South Pole and thus circumpolar on the latitude of Bali (8°S).[13]

Other planets

Pole stars of other planets are defined analogously: they are stars (brighter than 6th magnitude, i.e., visible to the naked eye under ideal conditions) that most closely coincide with the projection of the planet's axis of rotation onto the Celestial sphere. Different planets have different pole stars because their axes are oriented differently. (See Poles of astronomical bodies.)

- Alpha Pictoris is the south pole star of Mercury while Omicron Draconis is the north star.[14]

- 42 Draconis is the closest star to the northern pole of Venus. Eta¹ Doradus is the closest to the south pole.

- Delta Doradus is the south pole star of the Moon.

- Kappa Velorum is only a couple of degrees from the south Celestial pole of Mars. The top two stars in the Northern Cross, Sadr and Deneb, point to the north Celestial pole of Mars.[15]

- The north pole of Jupiter is a little over two degrees away from Zeta Draconis, while its south pole is HD 40455, a relatively faint (magnitude 6.63) star in Dorado.

- Delta Octantis is the south pole star of Saturn.

- Eta Ophiuchi is the north pole star of Uranus and 15 Orionis is its south pole star.

- The north pole of Neptune points to a spot midway between Gamma and Delta Cygni. Its south pole star is Gamma Velorum.

See also

- Astronomy on Mars#Celestial poles and ecliptic

- Celestial equator

- Celestial navigation

- Circumpolar star

- Myōken Bosatsu

- Voyages of Christopher Columbus

References

- ↑ implied by Johannes Kepler (cynosurae septem stellas consideravit quibus cursum navigationis dirigebant Phoenices): "Notae ad Scaligeri Diatribam de Aequinoctiis" in Kepleri Opera Omnia ed. Ch. Frisch, vol. 8.1 (1870) p. 290

- ↑ cited after J. O. Halliwell, (ed.), The Works of William Shakespeare vol. 5 (1856), p. 40.]

- ↑ Conversations-Lexicon Für Bildende Kunst vol. 7 (1857), 141f.

- ↑ A. Maas,"The Name of Mary", The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912)

- ↑ stella maris, sive illuminatrix Maria, inter fluctivagas undas pelagi, fide ac moribus sequenda est, ne mergamur undis diluvii PL vol. 120, p. 94.

- ↑ Gemmae Frisii de astrolabo catholico liber: quo latissime patentis instrumenti multiplex usus explicatur, & quicquid uspiam rerum mathematicarum tradi possit continetur, Steelsius (1556), p. 20

- ↑ "Star Tales: Ursa Minor". Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- ↑ Jean Meeus, Mathematical Astronomy Morsels Ch.50; Willmann-Bell 1997

- ↑ "Sigma Octantis". Jumk.De. 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "The North Star: Polaris". Space.com. May 7, 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Hobbs, Trace (May 21, 2013). "Night Sky Near the Equator". Wordpress. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/moonkmft/Articles/Precession.html

- ↑ Kieron Taylor (1 March 1994). "Precession". Sheffield Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ↑ 2004. Starry Night Pro, Version 5.8.4. Imaginova. ISBN 978-0-07-333666-4. www.starrynight.com

- ↑ http://www.eknent.com/etc/mars_np.png

External links

| Look up pole star in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Pole Star in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "HIP 11767". Hipparcos, the New Reduction. Retrieved 2011-03-01.