Lockheed P-38 Lightning

| P-38 Lightning | |

|---|---|

| |

| P-38H of the AAF Tactical Center, Orlando Army Air Base, Florida, carrying two 1,000 lb bombs during capability tests in March 1944[1] | |

| Role | Heavy fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed |

| Designer | Clarence "Kelly" Johnson |

| First flight | 27 January 1939 |

| Introduction | July 1941[2] |

| Retired | 1965 Honduran Air Force[3] |

| Primary users | United States Army Air Forces Free French Air Force |

| Produced | 1941–45 |

| Number built | 10,037[4] |

| Unit cost | |

| Developed into | Lockheed XP-49 Lockheed XP-58 |

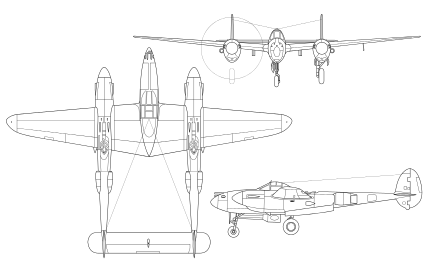

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is a World War II-era American piston-engined fighter aircraft. Developed to a United States Army Air Corps requirement, the P-38 had distinctive twin booms and a central nacelle containing the cockpit and armament. Allied propaganda claimed it had been nicknamed the fork-tailed devil (German: der Gabelschwanz-Teufel) by the Luftwaffe and "two planes, one pilot" (2飛行機、1パイロット Ni hikōki, ippairotto) by the Japanese.[7] The P-38 was used for interception, dive bombing, level bombing, ground attack, night fighting, photo reconnaissance, radar and visual pathfinding for bombers and evacuation missions,[8] and extensively as a long-range escort fighter when equipped with drop tanks under its wings.

The P-38 was used most successfully in the Pacific Theater of Operations and the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations as the aircraft of America's top aces, Richard Bong (40 victories), Thomas McGuire (38 victories) and Charles H. MacDonald (27 victories). In the South West Pacific theater, the P-38 was the primary long-range fighter of United States Army Air Forces until the appearance of large numbers of P-51D Mustangs toward the end of the war.[9][10]

The P-38 was unusually quiet for a fighter, the exhaust muffled by the turbo-superchargers. It was extremely forgiving and could be mishandled in many ways but the rate of roll in the early versions was too slow for it to excel as a dogfighter.[11] The P-38 was the only American fighter aircraft in high-volume production throughout American involvement in the war, from Pearl Harbor to Victory over Japan Day.[12] At the end of the war, orders for 1,887 more were cancelled.[13]

Design and development

Lockheed designed the P-38 in response to a February 1937 specification from the United States Army Air Corps. Circular Proposal X-608 was a set of aircraft performance goals authored by First Lieutenants Benjamin S. Kelsey and Gordon P. Saville for a twin-engine, high-altitude "interceptor" having "the tactical mission of interception and attack of hostile aircraft at high altitude."[14] In 1977, Kelsey recalled he and Saville drew up the specification using the word interceptor as a way to bypass the inflexible Army Air Corps requirement for pursuit aircraft to carry no more than 500 lb (227 kg) of armament including ammunition, as well as the restriction of single-seat aircraft to one engine. Kelsey was looking for a minimum of 1,000 lb (454 kg) of armament.[15] Kelsey and Saville aimed to get a more capable fighter, better at dog-fighting and at high-altitude combat. Specifications called for a maximum airspeed of at least 360 mph (580 km/h) at altitude, and a climb to 20,000 ft (6,100 m) within six minutes,[16] the toughest set of specifications USAAC had ever presented. The unbuilt Vultee XP1015 was designed to the same requirement, but was not advanced enough to merit further investigation. A similar single-engine proposal was issued at the same time, Circular Proposal X-609, in response to which the Bell P-39 Airacobra was designed.[17] Both proposals required liquid-cooled Allison V-1710 engines with turbo-superchargers and gave extra points for tricycle landing gear.

The Lockheed design team, under the direction of Hall Hibbard and Clarence "Kelly" Johnson, considered a range of twin-engine configurations, including both engines in a central fuselage with push–pull propellers.[18]

The eventual configuration was rare in terms of contemporary fighter aircraft design, with only the preceding Fokker G.1, the contemporary Focke-Wulf Fw 189 Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft, and the later Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter having a similar planform. The Lockheed team chose twin booms to accommodate the tail assembly, engines, and turbo-superchargers, with a central nacelle for the pilot and armament. The XP-38 gondola mockup was designed to mount two .50-caliber (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns with 200 rounds per gun (rpg), two .30-caliber (7.62 mm) Brownings with 500 rpg, and a T1 Army Ordnance 23 mm (.90 in) autocannon with a rotary magazine as a substitute for the non-existent 25 mm Hotchkiss aircraft autocannon specified by Kelsey and Saville.[19] In the YP-38s, a 37 mm (1.46 in) M9 autocannon with 15 rounds replaced the T1.[20] The 15 rounds were in three five-round clips, an unsatisfactory arrangement according to Kelsey, and the M9 did not perform reliably in flight. Further armament experiments from March to June 1941 resulted in the P-38E combat configuration of four M2 Browning machine guns, and one Hispano 20 mm (.79 in) autocannon with 150 rounds.[21]

Clustering all the armament in the nose was unusual in U.S. aircraft, which typically used wing-mounted guns with trajectories set up to crisscross at one or more points in a convergence zone. Nose-mounted guns did not suffer from having their useful ranges limited by pattern convergence, meaning that good pilots could shoot much farther. A Lightning could reliably hit targets at any range up to 1,000 yd (910 m), whereas the wing guns of other fighters were optimized for a specific range.[22] The rate of fire was about 650 rounds per minute for the 20×110 mm cannon round (130-gram shell) at a muzzle velocity of about 2,850 ft/s (870 m/s), and for the .50-caliber machine guns (51-gram rounds), about 850 rpm at 2,900 ft/s (880 m/s) velocity. Combined rate of fire was over 4,000 rpm with roughly every sixth projectile a 20 mm shell.[23] The duration of sustained firing for the 20 mm cannon was approximately 14 seconds while the .50-caliber machine guns worked for 35 seconds if each magazine was fully loaded with 500 rounds, or for 21 seconds if 300 rounds were loaded to save weight for long distance flying.

The Lockheed design incorporated tricycle undercarriage and a bubble canopy, and featured two 1,000 hp (746 kW) turbosupercharged 12-cylinder Allison V-1710 engines fitted with counter-rotating propellers to eliminate the effect of engine torque, with the turbochargers positioned behind the engines, the exhaust side of the units exposed along the dorsal surfaces of the booms.[24] Counter-rotation was achieved by the use of "handed" engines, which meant the crankshaft of each engine turned in the opposite direction of its counterpart, a relatively easy task for a modular-design aircraft powerplant as the V-1710.

The P-38 was the first American fighter to make extensive use of stainless steel and smooth, flush-riveted butt-jointed aluminum skin panels.[25] It was also the first military airplane to fly faster than 400 mph (640 km/h) in level flight.[26][27]

XP-38 and YP-38 prototypes

Lockheed won the competition on 23 June 1937 with its Model 22 and was contracted to build a prototype XP-38[28] for US$163,000, though Lockheed's own costs on the prototype would add up to US$761,000.[29] Construction began in July 1938, and the XP-38 first flew on 27 January 1939 at the hands of Ben Kelsey.[30][Note 1]

Kelsey then proposed a speed dash to Wright Field on 11 February 1939 to relocate the aircraft for further testing. General Henry "Hap" Arnold, commander of the USAAC, approved of the record attempt and recommended a cross-country flight to New York. The flight set a speed record by flying from California to New York in seven hours and two minutes, not counting two refueling stops,[24] but the aircraft was downed by carburetor icing short of the Mitchel Field runway in Hempstead, New York and was wrecked. However, on the basis of the record flight, the Air Corps ordered 13 YP-38s on 27 April 1939 for US$134,284 each.[4][32] (The "Y" in "YP" was the USAAC's designation for a prototype, while the "X" in "XP" was for experimental.) Lockheed's Chief test pilot Tony LeVier angrily characterized the accident as an unnecessary publicity stunt,[33] but according to Kelsey, the loss of the prototype, rather than hampering the program, sped the process by cutting short the initial test series.[34] The success of the aircraft design contributed to Kelsey's promotion to captain in May 1939.

Manufacture of YP-38s fell behind schedule, at least partly because of the need for mass-production suitability making them substantially different in construction from the prototype. Another factor was the sudden required expansion of Lockheed's facility in Burbank, taking it from a specialized civilian firm dealing with small orders to a large government defense contractor making Venturas, Harpoons, Lodestars, Hudsons, and designing the Constellation for TWA. The first YP-38 was not completed until September 1940, with its maiden flight on 17 September.[36] The 13th and final YP-38 was delivered to the Air Corps in June 1941; 12 aircraft were retained for flight testing and one for destructive stress testing. The YPs were substantially redesigned and differed greatly in detail from the hand-built XP-38. They were lighter and included changes in engine fit. The propeller rotation was reversed, with the blades spinning outward (away from the cockpit) at the top of their arc, rather than inward as before. This improved the aircraft's stability as a gunnery platform.[37]

High-speed compressibility problems

Test flights revealed problems initially believed to be tail flutter. During high-speed flight approaching Mach 0.68, especially during dives, the aircraft's tail would begin to shake violently and the nose would tuck under, steepening the dive. Once caught in this dive, the fighter would enter a high-speed compressibility stall and the controls would lock up, leaving the pilot no option but to bail out (if possible) or remain with the aircraft until it got down to denser air, where he might have a chance to pull out. During a test flight in May 1941, USAAC Major Signa Gilkey managed to stay with a YP-38 in a compressibility lockup, riding it out until he recovered gradually using elevator trim.[24] Lockheed engineers were very concerned at this limitation but first had to concentrate on filling the current order of aircraft. In late June 1941, the Army Air Corps was renamed the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), and a total of 65 Lightnings were finished for the service by September 1941 with more on the way for the USAAF, the Royal Air Force (RAF), and the Free French Air Force operating from England.

By November 1941, many of the initial assembly-line challenges had been met, which freed up time for the engineering team to tackle the problem of frozen controls in a dive. Lockheed had a few ideas for tests that would help them find an answer. The first solution tried was the fitting of spring-loaded servo tabs on the elevator trailing edge designed to aid the pilot when control yoke forces rose over 30 pounds-force (130 N), as would be expected in a high-speed dive. At that point, the tabs would begin to multiply the effort of the pilot's actions. The expert test pilot, 43-year-old[38] Ralph Virden, was given a specific high-altitude test sequence to follow and was told to restrict his speed and fast maneuvering in denser air at low altitudes, since the new mechanism could exert tremendous leverage under those conditions. A note was taped to the instrument panel of the test craft underscoring this instruction. On 4 November 1941, Virden climbed into YP-38 #1 and completed the test sequence successfully, but 15 minutes later was seen in a steep dive followed by a high-G pullout. The tail unit of the aircraft failed at about 3,500 ft (1,000 m) during the high-speed dive recovery; Virden was killed in the subsequent crash. The Lockheed design office was justifiably upset, but their design engineers could only conclude that servo tabs were not the solution for loss of control in a dive. Lockheed still had to find the problem; the Army Air Forces personnel were sure it was flutter and ordered Lockheed to look more closely at the tail.

In 1941 flutter was a familiar engineering problem related to a too-flexible tail, but the P-38's empennage was completely skinned in aluminum[Note 2] rather than fabric and was quite rigid. At no time did the P-38 suffer from true flutter.[39] To prove a point, one elevator and its vertical stabilizers were skinned with metal 63% thicker than standard, but the increase in rigidity made no difference in vibration. Army Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth B. Wolfe (head of Army Production Engineering) asked Lockheed to try external mass balances above and below the elevator, though the P-38 already had large mass balances elegantly placed within each vertical stabilizer. Various configurations of external mass balances were equipped, and dangerously steep test flights were flown to document their performance. Explaining to Wolfe in Report No. 2414, Kelly Johnson wrote "the violence of the vibration was unchanged and the diving tendency was naturally the same for all conditions."[40] The external mass balances did not help at all. Nonetheless, at Wolfe's insistence, the additional external balances were a feature of every P-38 built from then on.[41]

Johnson said in his autobiography[42] that he pleaded with NACA to do model tests in its wind tunnel. They already had experience of models thrashing around violently at speeds approaching those requested and did not want to risk damaging their tunnel. Gen. Arnold, head of Army Air Forces, ordered them to run the tests, which were done up to Mach 0.74.[43] The P-38's dive problem was revealed to be the center of pressure moving back toward the tail when in high-speed airflow. The solution was to change the geometry of the wing's lower surface when diving in order to keep lift within bounds of the top of the wing. In February 1943, quick-acting dive flaps were tried and proven by Lockheed test pilots. The dive flaps were installed outboard of the engine nacelles, and in action they extended downward 35° in 1.5 seconds. The flaps did not act as a speed brake; they affected the pressure distribution in a way that retained the wing's lift.[44]

Late in 1943, a few hundred dive flap field modification kits were assembled to give North African, European and Pacific P-38s a chance to withstand compressibility and expand their combat tactics. Unfortunately, these crucial flaps did not always reach their destination. In March 1944, 200 dive flap kits intended for European Theater of Operations (ETO) P-38Js were destroyed in a mistaken identification incident in which an RAF fighter shot down the Douglas C-54 Skymaster (mistaken for an Fw 200) taking the shipment to England. Back in Burbank, P-38Js coming off the assembly line in spring 1944 were towed out to the ramp and modified in the open air. The flaps were finally incorporated into the production line in June 1944 on the last 210 P-38Js. Despite testing having proved the dive flaps effective in improving tactical maneuvers, a 14-month delay in production limited their implementation, with only the final half of all Lightnings built having the dive flaps installed as an assembly-line sequence.[45]

Johnson later recalled:

I broke an ulcer over compressibility on the P-38 because we flew into a speed range where no one had ever been before, and we had difficulty convincing people that it wasn't the funny-looking airplane itself, but a fundamental physical problem. We found out what happened when the Lightning shed its tail and we worked during the whole war to get 15 more kn [28 km/h] of speed out of the P-38. We saw compressibility as a brick wall for a long time. Then we learned how to get through it.[46]

Buffeting was another early aerodynamic problem, difficult to distinguish from compressibility as both were reported by test pilots as "tail shake". Buffeting came about from airflow disturbances ahead of the tail; the airplane would shake at high speed. Leading edge wing slots were tried as were combinations of filleting between the wing, cockpit and engine nacelles. Air tunnel test number 15 solved the buffeting completely and its fillet solution was fitted to every subsequent P-38 airframe. Fillet kits were sent out to every squadron flying Lightnings. The problem was traced to a 40% increase in air speed at the wing-fuselage junction where the thickness/chord ratio was highest. An airspeed of 500 mph (800 km/h) at 25,000 ft (7,600 m) could push airflow at the wing-fuselage junction close to the speed of sound. Filleting solved the buffeting problem for the P-38E and later models.[39]

Another issue with the P-38 arose from its unique design feature of outwardly rotating (at the "tops" of the propeller arcs) counter-rotating propellers. Losing one of two engines in any twin-engine non-centerline thrust aircraft on takeoff creates sudden drag, yawing the nose toward the dead engine and rolling the wingtip down on the side of the dead engine. Normal training in flying twin-engine aircraft when losing an engine on takeoff is to push the remaining engine to full throttle to maintain airspeed; if a pilot did that in the P-38, regardless of which engine had failed, the resulting engine torque and p-factor force produced a sudden uncontrollable yawing roll, and the aircraft would flip over and hit the ground. Eventually, procedures were taught to allow a pilot to deal with the situation by reducing power on the running engine, feathering the prop on the failed engine, and then increasing power gradually until the aircraft was in stable flight. Single-engine takeoffs were possible, though not with a full fuel and ammunition load.[47] This same design feature was present from its earliest days on both the Luftwaffe twin-engine Henschel Hs 129 ground-attack aircraft, and from the fourth prototype onwards of the otherwise troubled Heinkel He 177A heavy bomber.[48]

The engines were unusually quiet because the exhausts were muffled by the General Electric turbo-superchargers on the twin Allison V12s.[49] There were early problems with cockpit temperature regulation; pilots were often too hot in the tropical sun as the canopy could not be fully opened without severe buffeting and were often too cold in northern Europe and at high altitude, as the distance of the engines from the cockpit prevented easy heat transfer. Later variants received modifications (such as electrically heated flight suits) to solve these problems.

On 20 September 1939, before the YP-38s had been built and flight tested, the USAAF ordered 66 initial production P-38 Lightnings, 30 of which were delivered to the USAAF in mid-1941, but not all these aircraft were armed. The unarmed aircraft were subsequently fitted with four .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns (instead of the two .50 in/12.7 mm and two .30 in/7.62 mm of their predecessors) and a 37 mm (1.46 in) cannon. They also had armored glass, cockpit armor and fluorescent cockpit controls.[50] One was completed with a pressurized cabin on an experimental basis and designated XP-38A.[51] Due to reports the USAAF was receiving from Europe, the remaining 36 in the batch were upgraded with small improvements such as self-sealing fuel tanks and enhanced armor protection to make them combat-capable. The USAAF specified that these 36 aircraft were to be designated P-38D. As a result, there never were any P-38Bs or P-38Cs. The P-38D's main role was to work out bugs and give the USAAF experience with handling the type.[52]

In March 1940, the French and the British, through the Anglo-French Purchasing Committee, ordered a total of 667 P-38s for US$100M,[53] designated Model 322F for the French and Model 322B for the British. The aircraft would be a variant of the P-38E. The overseas Allies wished for complete commonality of Allison engines with the large numbers of Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks both nations had on order, and thus ordered the Model 322 twin right-handed engines instead of counter-rotating ones and without turbo-superchargers.[54][Note 3] Performance was supposed to be 400 mph at 16,900 feet.[55] After the fall of France in June 1940, the British took over the entire order and gave the aircraft the service name "Lightning." By June 1941, the War Ministry had cause to reconsider their earlier aircraft specifications based on experience gathered in the Battle of Britain and The Blitz.[56] British displeasure with the Lockheed order came to the fore in July, and on 5 August 1941 they modified the contract such that 143 aircraft would be delivered as previously ordered, to be known as "Lightning (Mark) I," and 524 would be upgraded to US-standard P-38E specifications with a top speed of 415 mph at 20,000 feet guaranteed, to be called "Lightning II" for British service.[56] Later that summer an RAF test pilot reported back from Burbank with a poor assessment of the "tail flutter" situation, and the British cancelled all but three of the 143 Lightning Is.[56] As a loss of approximately US$15M was involved, Lockheed reviewed their contracts and decided to hold the British to the original order. Negotiations grew bitter and stalled.[56] Everything changed after the 7 December, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor after which the United States government seized some 40 of the Model 322s for West Coast defense;[57] subsequently all British Lightnings were delivered to the USAAF starting in January 1942. The USAAF lent the RAF three of the aircraft, which were delivered by sea in March 1942[58] and were test flown no earlier than May[59] at Cunliffe-Owen Aircraft Swaythling, the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment and the Royal Aircraft Establishment.[56] The A&AEE example was unarmed, lacked turbochargers and restricted to 300 mph; though the undercarriage was praised and flight on one engine described as comfortable.[60] These three were subsequently returned to the USAAF; one in December 1942 and the others in July 1943.[58] Of the remaining 140 Lightning Is, 19 were not modified and were designated by the USAAF as RP-322-I ('R' for 'Restricted', because non-counter-rotating propellers were considered more dangerous on takeoff), while 121 were converted to non-turbo-supercharged counter-rotating V-1710F-2 engines and designated P-322-II. All 121 were used as advanced trainers; a few were still serving that role in 1945.[59] A few RP-322s were later used as test modification platforms such as for smoke-laying canisters. The RP-322 was a fairly fast aircraft below 16,000 ft (4,900 m) and well-behaved as a trainer.[59][Note 4]

One result of the failed British/French order was to give the aircraft its name. Lockheed had originally dubbed the aircraft Atalanta from Greek mythology in the company tradition of naming planes after mythological and celestial figures, but the RAF name won out.[55]

Range extension

The strategic bombing proponents within the USAAF, called the Bomber Mafia by their ideological opponents, had established in the early 1930s a policy against research to create long-range fighters, which they thought would not be practical; this kind of research was not to compete for bomber resources. Aircraft manufacturers understood that they would not be rewarded if they installed subsystems on their fighters to enable them to carry drop tanks to provide more fuel for extended range. Lieutenant Kelsey, acting against this policy, risked his career in late 1941 when he convinced Lockheed to incorporate such subsystems in the P-38E model, without putting his request in writing. It is possible that Kelsey was responding to Colonel George William Goddard's observation that the US sorely needed a high-speed, long-range photo reconnaissance plane. Along with a change order specifying some P-38Es be produced without guns but with photo reconnaissance cameras, to be designated the F-4-1-LO, Lockheed began working out the problems of drop tank design and incorporation. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, eventually about 100 P-38Es were sent to a modification center near Dallas, Texas, or to the new Lockheed assembly plant B-6 (today the Burbank Airport), to be fitted with four K-17 aerial photography cameras. All of these aircraft were also modified to be able to carry drop tanks. P-38Fs were modified as well. Every Lightning from the P-38G onward was drop tank-capable off the assembly line.[61]

In March 1942, General Arnold made an off-hand comment that the US could avoid the German U-boat menace by flying fighters to the UK (rather than packing them onto ships). President Roosevelt pressed the point, emphasizing his interest in the solution. Arnold was likely aware of the flying radius extension work being done on the P-38, which by this time had seen success with small drop tanks in the range of 150 to 165 US gal (570 to 620 L), the difference in capacity being the result of subcontractor production variation. Arnold ordered further tests with larger drop tanks in the range of 300 to 310 US gal (1,100 to 1,200 L); the results were reported by Kelsey as providing the P-38 with a 2,500-mile (4,000 km) ferrying range.[61] Because of available supply, the smaller drop tanks were used to fly Lightnings to the UK, the plan called Operation Bolero.

Led by two Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, the first seven P-38s, each carrying two small drop tanks, left Presque Isle Army Air Field on June 23, 1942 for RAF Heathfield in Scotland. Their first refueling stop was made in far northeast Canada at Goose Bay. The second stop was a rough airstrip in Greenland called Bluie West One, and the third refueling stop was in Iceland at Keflavik. Other P-38s followed this route with some lost in mishaps, usually due to poor weather, low visibility, radio difficulties and navigational errors. Nearly 200 of the P-38Fs (and a few modified Es) were successfully flown across the Atlantic in July–August 1942, making the P-38 the first USAAF fighter to reach Britain and the first fighter ever to be delivered across the Atlantic under its own power.[62] Kelsey himself piloted one of the Lightnings, landing in Scotland on July 25.[63]

Operational history

The first unit to receive P-38s was the 1st Fighter Group. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the unit joined the 14th Pursuit Group in San Diego to provide West Coast defense.[64]

Entry to the war

The first Lightning to see active service was the F-4 version, a P-38E in which the guns were replaced by four K17 cameras.[65] They joined the 8th Photographic Squadron in Australia on 4 April 1942.[37] Three F-4s were operated by the Royal Australian Air Force in this theater for a short period beginning in September 1942.

On 29 May 1942, 25 P-38s began operating in the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. The fighter's long range made it well-suited to the campaign over the almost 1,200 mi (2,000 km)-long island chain, and it would be flown there for the rest of the war. The Aleutians were one of the most rugged environments available for testing the new aircraft under combat conditions. More Lightnings were lost due to severe weather and other conditions than enemy action; there were cases where Lightning pilots, mesmerized by flying for hours over gray seas under gray skies, simply flew into the water. On 9 August 1942, two P-38Es of the 343rd Fighter Group, 11th Air Force, at the end of a 1,000 mi (1,609 km) long-range patrol, happened upon a pair of Japanese Kawanishi H6K "Mavis" flying boats and destroyed them,[37] making them the first Japanese aircraft to be shot down by Lightnings.

European theater

After the Battle of Midway, the USAAF began redeploying fighter groups to Britain as part of Operation Bolero and Lightnings of the 1st Fighter Group were flown across the Atlantic via Iceland. On 14 August 1942, Second Lieutenant Elza Shahan of the 27th Fighter Squadron, and Second Lieutenant Joseph Shaffer of the 33rd Squadron operating out of Iceland shot down a Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor over the Atlantic. Shahan in his P-38F downed the Condor; Shaffer, flying either a P-40C or a P-39, had already set an engine on fire.[66] This was the first Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed by the USAAF.[67]

After 347 sorties with no enemy contact, the 1st, 14th and 82nd Fighter Groups were transferred to the 12th Air Force in North Africa as part of the force being built up for Operation Torch. On 19 November 1942, Lightnings escorted a group of B-17 Flying Fortress bombers on a raid over Tunis. On 5 April 1943, 26 P-38Fs of the 82nd claimed 31 enemy aircraft destroyed, helping to establish air superiority in the area and earning it the German nickname "der Gabelschwanz Teufel" – the Fork-Tailed Devil.[64] The P-38 remained active in the Mediterranean for the rest of the war. It was in this theatre that the P-38 suffered its heaviest losses in the air. On 25 August 1943, 13 P-38s were shot down in a single sortie by Jagdgeschwader 53 Bf 109s without achieving a single kill.[68] On 2 September, 10 P-38s were shot down, in return for a single kill, the 67-victory ace Franz Schiess (who was also the leading "Lightning" killer in the Luftwaffe with 17 destroyed).[68] Kurt Bühligen, third highest scoring German pilot on the Western front with 112 victories, recalled later: "The P-38 fighter (and the B-24) were easy to burn. Once in Africa we were six and met eight P-38s and shot down seven. One sees a great distance in Africa and our observers and flak people called in sightings and we could get altitude first and they were low and slow." [69] General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland was unimpressed with the P-38, declaring "it had similar shortcomings in combat to our Bf 110, our fighters were clearly superior to it."[70] Experiences over Germany had shown a need for long-range escort fighters to protect the Eighth Air Force's heavy bomber operations. The P-38Hs of the 55th Fighter Group were transferred to the Eighth in England in September 1943, and were joined by the 20th, 364th and 479th Fighter Groups soon after. P-38s soon joined Spitfires in escorting the early Fortress raids over Europe.[71]

Because its distinctive shape was less prone to cases of mistaken identity and friendly fire,[72] Lieutenant General Jimmy Doolittle, Commander of the 8th Air Force, chose to pilot a P-38 during the invasion of Normandy so that he could watch the progress of the air offensive over France.[73] At one point in the mission, Doolittle flick-rolled through a hole in the cloud cover, but his wingman, then-Major General Earle E. Partridge, was looking elsewhere and failed to notice Doolittle's quick maneuver, leaving Doolittle to continue on alone on his survey of the crucial battle. Of the P-38, Doolittle said that it was "the sweetest-flying plane in the sky".[74]

A little-known role of the P-38 in the European theater was that of fighter-bomber during the invasion of Normandy and the Allied advance across France into Germany. Assigned to the IX Tactical Air Command, the 370th Fighter Group and its P-38s initially flew missions from England, dive-bombing radar installations, enemy armor, troop concentrations and flak towers.[75] The 370th's group commander Howard F. Nichols and a squadron of his P-38 Lightnings attacked Field Marshal Günther von Kluge's headquarters in July 1944; Nichols himself skipped a 500 lb (227 kg) bomb through the front door.[76] The 370th later operated from Cardonville France, flying ground attack missions against gun emplacements, troops, supply dumps and tanks near Saint-Lô in July and in the Falaise–Argentan area in August 1944.[75] The 370th participated in ground attack missions across Europe until February 1945 when the unit changed over to the P-51 Mustang.

On 12 June 1943, a P-38G, while flying a special mission between Gibraltar and Malta or, perhaps, just after strafing the radar station of Capo Pula, landed on the airfield of Capoterra (Cagliari), in Sardinia, from navigation error due to a compass failure. Regia Aeronautica chief test pilot colonnello (Lieutenant Colonel) Angelo Tondi flew the aircraft to Guidonia airfield where the P-38G was evaluated. On 11 August 1943, Tondi took off to intercept a formation of about 50 bombers, returning from the bombing of Terni (Umbria). Tondi attacked B-17G "Bonny Sue", s.n. 42-30307, that fell off the shore of Torvaianica, near Rome, while six airmen parachuted out. According to US sources, he also damaged three more bombers on that occasion. On 4 September, the 301st BG reported the loss of B-17 "The Lady Evelyn," s.n. 42-30344, downed by "an enemy P-38".[77] War missions for that plane were limited, as the Italian petrol was too corrosive for the Lockheed's tanks.[78] Other Lightnings were eventually acquired by Italy for postwar service.

In a particular case when faced by more agile fighters at low altitudes in a constricted valley, Lightnings suffered heavy losses. On the morning of 10 June 1944, 96 P-38Js of the 1st and 82nd Fighter Groups took off from Italy for Ploiești, the third-most heavily defended target in Europe, after Berlin and Vienna.[79] Instead of bombing from high altitude as had been tried by the Fifteenth Air Force, USAAF planning had determined that a dive-bombing surprise attack, beginning at about 7,000 feet (2,100 m) with bomb release at or below 3,000 feet (900 m),[79] performed by 46 82nd Fighter Group P-38s, each carrying one 1,000-pound (500 kg) bomb, would yield more accurate results.[80] All of 1st Fighter Group and a few aircraft in 82nd Fighter Group were to fly cover, and all fighters were to strafe targets of opportunity on the return trip; a distance of some 1,255 miles (2,020 km), including a circuitous outward route made in an attempt to achieve surprise.[79]

Some 85 or 86 fighters arrived in Romania to find enemy airfields alerted, with a wide assortment of aircraft scrambling for safety. P-38s shot down several, including heavy fighters, transports and observation aircraft. At Ploiești, defense forces were fully alert, the target was concealed by smoke screen, and anti-aircraft fire was very heavy—seven Lightnings were lost to anti-aircraft fire at the target, and two more during strafing attacks on the return flight. German Bf 109 fighters from I./JG 53 and 2./JG 77 fought the Americans. Sixteen aircraft of the 71st Fighter Squadron were challenged by a large formation of Romanian single-seater IAR.81C fighters. The fight took place below 300 feet (100 m) in a narrow valley.[81] Herbert Hatch saw two IAR 81Cs that he misidentified as Focke-Wulf Fw 190s hit the ground after taking fire from his guns, and his fellow pilots confirmed three more of his kills. However, the outnumbered 71st Fighter Squadron took more damage than it dished out, losing nine aircraft. In all, the USAAF lost 22 aircraft on the mission. The Americans claimed 23 aerial victories, though Romanian and German fighter units admitted losing only one aircraft each.[82] Eleven enemy locomotives were strafed and left burning, and flak emplacements were destroyed, along with fuel trucks and other targets. Results of the bombing were not observed by the USAAF pilots because of the smoke. The dive-bombing mission profile was not repeated, though the 82nd Fighter Group was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for its part.[83]

After some disastrous raids in 1944 with B-17s escorted by P-38s and Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, Jimmy Doolittle, then head of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, went to the RAE, Farnborough, asking for an evaluation of the various American fighters. Test pilot Captain Eric Brown, Fleet Air Arm, recalled:

We had found out that the Bf 109 and the FW 190 could fight up to a Mach of 0.75, three-quarters the speed of sound. We checked the Lightning and it couldn't fly in combat faster than 0.68. So it was useless. We told Doolittle that all it was good for was photo-reconnaissance and had to be withdrawn from escort duties. And the funny thing is that the Americans had great difficulty understanding this because the Lightning had the two top aces in the Far East.[84]

After evaluation tests at Farnborough, the P-38 was kept in fighting service in Europe for a while longer. Although many failings were remedied with the introduction of the P-38J, by September 1944, all but one of the Lightning groups in the Eighth Air Force had converted to the P-51 Mustang. The Eighth Air Force continued to conduct reconnaissance missions using the F-5 variant.[64]

Pacific theater

The P-38 was used most extensively and successfully in the Pacific theater, where it proved ideally suited, combining excellent performance with exceptional range and the added reliability of two engines for long missions over water. The P-38 was used in a variety of roles, especially escorting bombers at altitudes of 18–25,000 ft (5,500–7,600 m). The P-38 was credited with destroying more Japanese aircraft than any other USAAF fighter.[4] Freezing cockpit temperatures were not a problem at low altitude in the tropics. In fact the cockpit was often too hot since opening a window while in flight caused buffeting by setting up turbulence through the tailplane. Pilots taking low altitude assignments would often fly stripped down to shorts, tennis shoes, and parachute. While the P-38 could not out-turn the A6M Zero and most other Japanese fighters when flying below 200 mph (320 km/h), its superior speed coupled with a good rate of climb meant that it could utilize energy tactics, making multiple high-speed passes at its target. Also its focused firepower was even more deadly to lightly armored Japanese warplanes than to the Germans'. The concentrated, parallel stream of bullets allowed aerial victory at much longer distances than fighters carrying wing guns. It is therefore ironic that Dick Bong, the United States' highest-scoring World War II air ace (40 victories solely in P-38s), would fly directly at his targets to make sure he hit them (as he himself acknowledged his poor shooting ability), in some cases flying through the debris of his target (and on one occasion colliding with an enemy aircraft which was claimed as a "probable" victory). The twin Allison engines performed admirably in the Pacific.

General George C. Kenney, commander of the USAAF Fifth Air Force operating in New Guinea, could not get enough P-38s; they had become his favorite fighter in November 1942 when one squadron, the 39th Fighter Squadron of the 35th Fighter Group, joined his assorted P-39s and P-40s. The Lightnings established local air superiority with their first combat action on 27 December 1942.[85][86][87][88][89] Kenney sent repeated requests to Arnold for more P-38s, and was rewarded with occasional shipments, but Europe was a higher priority in Washington.[90] Despite their small force, Lightning pilots began to compete in racking up scores against Japanese aircraft.

On 2–4 March 1943, P-38s flew top cover for 5th Air Force and Australian bombers and attack aircraft during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, in which eight Japanese troop transports and four escorting destroyers were sunk. Two P-38 aces from the 39th Fighter Squadron were killed on the second day of the battle: Bob Faurot and Hoyt "Curley" Eason (a veteran with five victories who had trained hundreds of pilots, including Dick Bong). In one notable engagement on 3 March 1943 P-38s escorted 13 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses as they bombed the Japanese convoy from a medium altitude of 7,000 feet which dispersed the convoy formation and reduced their concentrated anti-aircraft firepower. A B-17 was shot down and when Japanese Zero fighters machine-gunned some of the B-17 crew members that bailed out in parachutes, three P-38s promptly engaged and shot down five of the Zeros.[91][92][91][93].[94]

Isoroku Yamamoto

The Lightning figured in one of the most significant operations in the Pacific theater: the interception, on 18 April 1943, of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of Japan's naval strategy in the Pacific including the attack on Pearl Harbor. When American codebreakers found out that he was flying to Bougainville Island to conduct a front-line inspection, 16 P-38G Lightnings were sent on a long-range fighter-intercept mission, flying 435 miles (700 km) from Guadalcanal at heights of 10–50 ft (3–15 m) above the ocean to avoid detection. The Lightnings met Yamamoto's two Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" fast bomber transports and six escorting Zeros just as they arrived at the island. The first Betty crashed in the jungle and the second ditched near the coast. Two Zeros were also claimed by the American fighters with the loss of one P-38. Japanese search parties found Yamamoto's body at the jungle crash site the next day.[95]

Service record

The P-38's service record shows mixed results, which may reflect more on its employment than on flaws with the aircraft. The P-38's engine troubles at high altitudes only occurred with the Eighth Air Force. One reason for this was the inadequate cooling systems of the G and H models; the improved P-38 J and L had tremendous success flying out of Italy into Germany at all altitudes.[64] Until the -J-25 variant, P-38s were easily avoided by German fighters because of the lack of dive flaps to counter compressibility in dives. German fighter pilots not wishing to fight would perform the first half of a Split S and continue into steep dives because they knew the Lightnings would be reluctant to follow.

On the positive side, having two engines was a built-in insurance policy. Many pilots made it safely back to base after having an engine failure en route or in combat. On 3 March 1944, the first Allied fighters reached Berlin on a frustrated escort mission. Lieutenant Colonel Jack Jenkins of 55FG led the group of P-38H pilots, arriving with only half his force after flak damage and engine trouble took their toll. On the way into Berlin, Jenkins reported one rough-running engine, causing him to wonder if he would ever make it back. The B-17s he was supposed to escort never showed up, having turned back at Hamburg. Jenkins and his wingman were able to drop tanks and outrun enemy fighters to return home with three good engines between them.[96]

In the ETO, P-38s made 130,000 sorties with a loss of 1.3% overall, comparing favorably with ETO P-51s, which posted a 1.1% loss, considering that the P-38s were vastly outnumbered and suffered from poorly thought-out tactics. The majority of the P-38 sorties were made in the period prior to Allied air superiority in Europe, when pilots fought against a very determined and skilled enemy.[97] Lieutenant Colonel Mark Hubbard, a vocal critic of the aircraft, rated it the third best Allied fighter in Europe.[98] The Lightning's greatest virtues were long range, heavy payload, high speed, fast climb and concentrated firepower. The P-38 was a formidable fighter, interceptor and attack aircraft.

In the Pacific theater, the P-38 downed over 1,800 Japanese aircraft, with more than 100 pilots becoming aces by downing five or more enemy aircraft.[95] American fuel supplies contributed to a better engine performance and maintenance record, and range was increased with leaner mixtures. In the second half of 1944, the P-38L pilots out of Dutch New Guinea were flying 950 mi (1,530 km), fighting for fifteen minutes and returning to base.[99] Such long legs were invaluable until the P-47N and P-51D entered service.

Postwar operations

The end of the war left the USAAF with thousands of P-38s rendered obsolete by the jet age. The last P-38s in service with the United States Air Force were retired in 1949.[100] A total of 100 late-model P-38L and F-5 Lightnings were acquired by Italy through an agreement dated April 1946. Delivered, after refurbishing, at the rate of one per month, they finally were all sent to the AMI by 1952. The Lightnings served in 4 Stormo and other units including 3 Stormo, flying reconnaissance over the Balkans, ground attack, naval cooperation and air superiority missions. Due to old engines, pilot errors and lack of experience in operating heavy fighters, a large number of P-38s were lost in at least 30 accidents, many of them fatal. Despite this, many Italian pilots liked the P-38 because of its excellent visibility on the ground and stability on takeoff. The Italian P-38s were phased out in 1956; none survived the scrapyard.[101]

Surplus P-38s were also used by other foreign air forces with 12 sold to Honduras and 15 retained by China. Six F-5s and two unarmed black two-seater P-38s were operated by the Dominican Air Force based in San Isidro Airbase, Dominican Republic in 1947. The majority of wartime Lightnings present in the continental U.S. at the end of the war were put up for sale for US$1,200 apiece; the rest were scrapped. P-38s in distant theaters of war were bulldozed into piles and abandoned or scrapped; very few avoided that fate.

The CIA "Liberation Air Force" flew one P-38M to support the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'etat. On 27 June 1954, this aircraft dropped napalm bombs that destroyed the British cargo ship SS Springfjord, which was loading Guatemalan cotton[102] and coffee[103] for Grace Line[104] in Puerto San José.[105] In 1957, five Honduran P-38s bombed and strafed a village occupied by Nicaraguan forces during a border dispute between these two countries concerning part of Gracias a Dios Department.[106]

P-38s were popular contenders in the air races from 1946 through 1949, with brightly colored Lightnings making screaming turns around the pylons at Reno and Cleveland. Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier was among those who bought a Lightning, choosing a P-38J model and painting it red to make it stand out as an air racer and stunt flyer. Lefty Gardner, former B-24 and B-17 pilot and associate of the Confederate Air Force, bought a mid-1944 P-38L-1-LO that had been modified into an F-5G. Gardner painted it white with red and blue trim and named it White Lightnin'; he reworked its turbo systems and intercoolers for optimum low-altitude performance and gave it P-38F style air intakes for better streamlining. White Lightnin' was severely damaged in a crash landing during an air show demonstration and was bought, restored and repainted with a brilliant chrome finish by the company that owns Red Bull. The aircraft is now located in Austria.

F-5s were bought by aerial survey companies and employed for mapping. From the 1950s on, the use of the Lightning steadily declined, and only a little more than two dozen still exist, with few still flying. One example is a P-38L owned by the Lone Star Flight Museum in Galveston, Texas, painted in the colors of Charles H. MacDonald's Putt Putt Maru. Two other examples are F-5Gs which were owned and operated by Kargl Aerial Surveys in 1946, and are now located in Chino, California at Yanks Air Museum, and in McMinnville, Oregon at Evergreen Aviation Museum. The earliest-built surviving P-38, Glacier Girl, was recovered from the Greenland ice cap in 1992, fifty years after she crashed there on a ferry flight to the UK, and after a complete restoration, flew once again ten years after her recovery.

Production

| Variant | Built or Converted | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| XP-38 | 1 | Prototype |

| YP-38 | 13 | Evaluation aircraft |

| P-38 | 30 | Initial production aircraft |

| XP-38A | 1 | Pressurized cockpit |

| P-38D | 36 | Fitted with self-sealing fuel tanks/armored windshield |

| P-38E | 210 | First combat-ready variant, revised armament |

| F-4 | 100+ | reconnaissance aircraft based on P-38E |

| Model 322 | 3 | RAF order: twin right-hand props and no turbo |

| RP-322 | 147 | USAAF trainers |

| P-38F | 527 | First-fully combat-capable P-38 fighter |

| F-4A | 20 | reconnaissance aircraft based on P-38F |

| P-38G | 1,082 | Improved P-38F fighter |

| F-5A | 180 | reconnaissance aircraft based on P-38G |

| XF-5D | 1 | a one-off converted F-5A |

| P-38H | 601 | Automatic cooling system; Improved P-38G fighter |

| P-38J | 2,970 | new cooling and electrical systems |

| F-5B | 200 | reconnaissance aircraft based on P-38J |

| F-5C | 123 | reconnaissance aircraft converted from P-38J |

| F-5E | 705 | reconnaissance aircraft converted from P-38J/L |

| P-38K | 1 | paddle blade props; up-rated engines with a different propeller reduction ratio |

| P-38L-LO | 3,810 | Improved P-38J new engines; new rocket pylons |

| P-38L-VN | 113 | P-38L built by Vultee |

| F-5F | - | reconnaissance aircraft converted from P-38L |

| P-38M | 75 | night-fighter |

| F-5G | - | reconnaissance aircraft converted from P-38L |

Over 10,000 Lightnings were manufactured, becoming the only U.S. combat aircraft that remained in continuous production throughout the duration of American participation in World War II. The Lightning had a major effect on other aircraft; its wing, in a scaled-up form, was used on the Lockheed Constellation.[108]

P-38D and P-38Es

Delivered and accepted Lightning production variants began with the P-38D model. The few "hand made" YP-38s initially contracted were used as trainers and test aircraft. There were no Bs or Cs delivered to the government as the USAAF allocated the 'D' suffix to all aircraft with self-sealing fuel tanks and armor.[33] Many secondary but still initial teething tests were conducted utilizing the earliest D variants.[33]

The first combat-capable Lightning was the P-38E (and its photo-recon variant the F-4) which featured improved instruments, electrical, and hydraulic systems. Part-way through production, the older Hamilton Standard Hydromatic hollow steel propellers were replaced by new Curtiss Electric duraluminum propellers. The definitive (and now famous) armament configuration was settled upon, featuring four .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns with 500 rpg, and a 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano autocannon with 150 rounds.[109]

While the machine guns had been arranged symmetrically in the nose on the P-38D, they were "staggered" in the P-38E and later versions, with the muzzles protruding from the nose in the relative lengths of roughly 1:4:6:2. This was done to ensure a straight ammunition-belt feed into the weapons, as the earlier arrangement led to jamming.

The first P-38E rolled out of the factory in October 1941 as the Battle of Moscow filled the news wires of the world. Because of the versatility, redundant engines, and especially high speed and high altitude characteristics of the aircraft, as with later variants over a hundred P-38Es were completed in the factory or converted in the field to a photoreconnaissance variant, the F-4, in which the guns were replaced by four cameras. Most of these early reconnaissance Lightnings were retained stateside for training, but the F-4 was the first Lightning to be used in action in April 1942.

P-38Fs and P-38Gs

After 210 P-38Es were built, they were followed, starting in April 1942, by the P-38F, which incorporated racks inboard of the engines for fuel tanks or a total of 2,000 lb (907 kg) of bombs. Early variants did not enjoy a high reputation for maneuverability, though they could be agile at low altitudes if flown by a capable pilot, using the P-38's forgiving stall characteristics to their best advantage. From the P-38F-15 model onwards, a "combat maneuver" setting was added to the P-38's Fowler flaps. When deployed at the 8° maneuver setting, the flaps allowed the P-38 to out-turn many contemporary single-engined fighters at the cost of some added drag. However, early variants were hampered by high aileron control forces and a low initial rate of roll,[110] and all such features required a pilot to gain experience with the aircraft,[33] which in part was an additional reason Lockheed sent its representative to England, and later to the Pacific Theater.

The aircraft was still experiencing extensive teething troubles as well as being victimized by "urban legends", mostly involving inapplicable twin engine factors which had been designed out of the aircraft by Lockheed.[33] In addition to these, the early versions had a reputation as a "widow maker" as it could enter an unrecoverable dive due to a sonic surface effect at high sub-sonic speeds. The 527 P-38Fs were heavier, with more powerful engines that used more fuel, and were unpopular in the air war in Northern Europe.[33] Since the heavier engines were having reliability problems and with them, without external fuel tanks, the range of the P-38F was reduced, and since drop tanks themselves were in short supply as the fortunes in the Battle of the Atlantic had not yet swung the Allies' way, the aircraft became relatively unpopular in minds of the bomber command planning staffs despite being the longest ranged fighter first available to the 8th Air Force in sufficient numbers for long range escort duties.[33] Nonetheless, General Spaatz, then commander of the 8th Air Force in the UK, said of the P-38F: "I'd rather have an airplane that goes like hell and has a few things wrong with it, than one that won't go like hell and has a few things wrong with it."[74]

The P-38F was followed in early 1943 by the P-38G, utilizing more powerful Allisons of 1,400 hp (1,040 kW) each and equipped with a better radio. A dozen of the planned P-38G production were set aside to serve as prototypes for what would become the P-38J with further uprated Allison V-1710F-17 engines (1,425 hp/1,060 kW each) in redesigned booms which featured chin-mounted intercoolers in place of the original system in the leading edge of the wings and more efficient radiators. Lockheed subcontractors, however, were initially unable to supply both of Burbank's twin production lines with a sufficient quantity of new core intercoolers and radiators. War Production Board planners were unwilling to sacrifice production, and one of the two remaining prototypes received the new engines but retained the old leading edge intercoolers and radiators.

As the P-38H, 600 of these stop-gap Lightnings with an improved 20 mm cannon and a bomb capacity of 3,200 lb (1,450 kg).were produced on one line while the near-definitive P-38J began production on the second line. The Eighth Air Force was experiencing high altitude and cold weather issues which, while not unique to the aircraft, were perhaps more severe as the turbo-superchargers upgrading the Allisons were having their own reliability issues making the aircraft more unpopular with senior officers out of the line.[33] This was a situation unduplicated on all other fronts where the commands were clamoring for as many P-38s as they could get.[33] Both the P-38G and P-38H models' performance was restricted by an intercooler system integral to the wing's leading edge which had been designed for the YP-38's less powerful engines. At the higher boost levels, the new engine's charge air temperature would increase above the limits recommended by Allison and would be subject to detonation if operated at high power for extended periods of time. Reliability was not the only issue, either. For example, the reduced power settings required by the P-38H did not allow the maneuvering flap to be used to good advantage at high altitude.[111] All these problems really came to a head in the unplanned P-38H and sped the Lightning's eventual replacement in the Eighth Air Force; fortunately the Fifteenth Air Force were glad to get them.

Some P-38G production was diverted on the assembly line to F-5A reconnaissance aircraft. An F-5A was modified to an experimental two-seat reconnaissance configuration as the XF-5D, with a plexiglas nose, two machine guns and additional cameras in the tail booms.

P-38J, P-38L

The P-38J was introduced in August 1943. The turbo-supercharger intercooler system on previous variants had been housed in the leading edges of the wings and had proven vulnerable to combat damage and could burst if the wrong series of controls were mistakenly activated. In the P-38J model, the streamlined engine nacelles of previous Lightnings were changed to fit the intercooler radiator between the oil coolers, forming a "chin" that visually distinguished the J model from its predecessors. While the P-38J used the same V-1710-89/91 engines as the H model, the new core-type intercooler more efficiently lowered intake manifold temperatures and permitted a substantial increase in rated power. The leading edge of the outer wing was fitted with 55 gal (208 l) fuel tanks, filling the space formerly occupied by intercooler tunnels, but these were omitted on early P-38J blocks due to limited availability.[112]

The final 210 J models, designated P-38J-25-LO, alleviated the compressibility problem through the addition of a set of electrically actuated dive recovery flaps just outboard of the engines on the bottom centerline of the wings. With these improvements, a USAAF pilot reported a dive speed of almost 600 mph (970 km/h), although the indicated air speed was later corrected for compressibility error, and the actual dive speed was lower.[113] Lockheed manufactured over 200 retrofit modification kits to be installed on P-38J-10-LO and J-20-LO already in Europe, but the USAAF C-54 carrying them was shot down by an RAF pilot who mistook the Douglas transport for a German Focke-Wulf Condor.[114] Unfortunately, the loss of the kits came during Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier's four-month morale-boosting tour of P-38 bases. Flying a new Lightning named "Snafuperman", modified to full P-38J-25-LO specifications at Lockheed's modification center near Belfast, LeVier captured the pilots' full attention by routinely performing maneuvers during March 1944 that common Eighth Air Force wisdom held to be suicidal. It proved too little, too late, because the decision had already been made to re-equip with Mustangs.[115]

The P-38J-25-LO production block also introduced hydraulically boosted ailerons, one of the first times such a system was fitted to a fighter. This significantly improved the Lightning's rate of roll and reduced control forces for the pilot. This production block and the following P-38L model are considered the definitive Lightnings, and Lockheed ramped up production, working with subcontractors across the country to produce hundreds of Lightnings each month.

There were two P-38Ks developed from 1942 to 1943, one official and one an internal Lockheed experiment. The first was actually a battered RP-38E "piggyback" test mule previously used by Lockheed to test the P-38J chin intercooler installation, now fitted with paddle-bladed "high activity" Hamilton Standard Hydromatic propellers similar to those used on the P-47. The new propellers required spinners of greater diameter, and the mule's crude, hand-formed sheet steel cowlings were further stretched to blend the spinners into the nacelles. It retained its "piggyback" configuration that allowed an observer to ride behind the pilot. With Lockheed's AAF representative as a passenger and the maneuvering flap deployed to offset Army Hot Day conditions, the old "K-Mule" still climbed to 45,000 feet (14,000 m). With a fresh coat of paint covering its crude hand-formed steel cowlings, this RP-38E acts as stand-in for the "P-38K-1-LO" in the model's only picture.[116]

The 12th G model originally set aside as a P-38J prototype was re-designated P-38K-1-LO and fitted with the aforementioned paddle-blade propellers and new Allison V-1710-75/77 (F15R/L) powerplants rated at 1,875 bhp (1,398 kW) at War Emergency Power. These engines were geared 2.36 to 1, unlike the standard P-38 ratio of 2 to 1. The AAF took delivery in September 1943, at Eglin Field. In tests, the P-38K-1 achieved 432 mph (695 km/h) at military power and was predicted to exceed 450 mph (720 km/h) at War Emergency Power with a similar increase in load and range. The initial climb rate was 4,800 ft (1,500 m)/min and the ceiling was 46,000 ft (14,000 m). It reached 20,000 ft (6,100 m) in five minutes flat; this with a coat of camouflage paint which added weight and drag. Although it was judged superior in climb and speed to the latest and best fighters from all AAF manufacturers, the War Production Board refused to authorize P-38K production due to the two-to-three-week interruption in production necessary to implement cowling modifications for the revised spinners and higher thrust line.[116] Some have also doubted Allison's ability to deliver the F15 engine in quantity.[117] As promising as it had looked, the P-38K project came to a halt.

The P-38L was the most numerous variant of the Lightning, with 3,923 built, 113 by Consolidated-Vultee in their Nashville plant. It entered service with the USAAF in June 1944, in time to support the Allied invasion of France on D-Day. Lockheed production of the Lightning was distinguished by a suffix consisting of a production block number followed by "LO," for example "P-38L-1-LO", while Consolidated-Vultee production was distinguished by a block number followed by "VN," for example "P-38L-5-VN."

The P-38L was the first Lightning fitted with zero-length rocket launchers. Seven high velocity aircraft rockets (HVARs) on pylons beneath each wing, and later, five rockets on each wing on "Christmas tree" launch racks which added 1,365 lb (619 kg) to the aircraft.[118] The P-38L also had strengthened stores pylons to allow carriage of 2,000 lb (900 kg) bombs or 300 US gal (1,100 l) drop tanks.

Lockheed modified 200 P-38J airframes in production to become unarmed F-5B photo-reconnaissance aircraft, while hundreds of other P-38Js and P-38Ls were modified at Lockheed's Dallas Modification Center to become F-5Cs, F-5Es, F-5Fs, and F-5Gs. A few P-38Ls were field-modified to become two-seat TP-38L familiarization trainers. During and after June 1948, the remaining J and L variants were designated ZF-38J and ZF-38L, with the "ZF" designator (meaning "obsolete fighter") replacing the "P for Pursuit" category.

Late model Lightnings were delivered unpainted, as per USAAF policy established in 1944. At first, field units tried to paint them, since pilots worried about being too visible to the enemy, but it turned out the reduction in weight and drag was a minor advantage in combat.

The P-38L-5, the most common sub-variant of the P-38L, had a modified cockpit heating system consisting of a plug-socket in the cockpit into which the pilot could plug his heat-suit wire for improved comfort. These Lightnings also received the uprated V-1710-112/113 (F30R/L) engines, and this dramatically lowered the amount of engine failure problems experienced at high altitude so commonly associated with European operations.

Pathfinders, night-fighter and other variants

The Lightning was modified for other roles. In addition to the F-4 and F-5 reconnaissance variants, a number of P-38Js and P-38Ls were field-modified as formation bombing "pathfinders" or "droopsnoots", fitted with a glazed nose with a Norden bombsight, or a H2X radar "bombing through overcast" nose. A pathfinder would lead a formation of other P-38s, each overloaded with two 2,000 lb (907 kg) bombs; the entire formation releasing when the pathfinder did.

A number of Lightnings were modified as night fighters. There were several field or experimental modifications with different equipment fits that finally led to the "formal" P-38M night fighter, or Night Lightning. A total of 75 P-38Ls were modified to the Night Lightning configuration, painted flat-black with conical flash hiders on the guns, an AN/APS-6 radar pod below the nose, and a second cockpit with a raised canopy behind the pilot's canopy for the radar operator. The headroom in the rear cockpit was limited, requiring radar operators who were preferably short in stature.

The P-38M was faster than the purpose-built Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter. The night Lightnings saw some combat duty in the Pacific towards the end of the war but none engaged in combat.

One of the initial production P-38s had its turbo-superchargers removed, with a secondary cockpit placed in one of the booms to examine how flightcrew would respond to such an "asymmetric" cockpit layout. One P-38E was fitted with an extended central nacelle to accommodate a tandem-seat cockpit with dual controls, and was later fitted with a laminar flow wing.

Very early in the Pacific War, a scheme was proposed to fit Lightnings with floats to allow them to make long-range ferry flights. The floats would be removed before the aircraft went into combat. There were concerns that saltwater spray would corrode the tailplane, and so in March 1942, P-38E 41-1986 was modified with a tailplane raised some 16–18 in (41–46 cm), booms lengthened by two feet and a rearward-facing second seat added for an observer to monitor the effectiveness of the new arrangement. A second version was crafted on the same airframe with the twin booms given greater sideplane area to augment the vertical rudders. This arrangement was removed and a final third version was fabricated that had the booms returned to normal length but the tail raised 33 in (84 cm). All three tail modifications were designed by George H. "Bert" Estabrook. The final version was used for a quick series of dive tests on 7 December 1942 in which Milo Burcham performed the test maneuvers and Kelly Johnson observed from the rear seat. Johnson concluded that the raised floatplane tail gave no advantage in solving the problem of compressibility. At no time was this P-38E testbed airframe actually fitted with floats, and the idea was quickly abandoned as the U.S. Navy proved to have enough sealift capacity to keep up with P-38 deliveries to the South Pacific.[119]

Still another P-38E was used in 1942 to tow a Waco troop glider as a demonstration. However, there proved to be plenty of other aircraft, such as Douglas C-47 Skytrains, available to tow gliders, and the Lightning was spared this duty.

Standard Lightnings were used as crew and cargo transports in the South Pacific. They were fitted with pods attached to the underwing pylons, replacing drop tanks or bombs, that could carry a single passenger in a lying-down position, or cargo. This was a very uncomfortable way to fly. Some of the pods were not even fitted with a window to let the passenger see out or bring in light.

Lockheed proposed a carrier-based Model 822 version of the Lightning for the United States Navy. The Model 822 would have featured folding wings, an arresting hook, and stronger undercarriage for carrier operations. The navy was not interested, as they regarded the Lightning as too big for carrier operations and did not like liquid-cooled engines anyway, and the Model 822 never went beyond the paper stage. However, the navy did operate four land-based F-5Bs in North Africa, inherited from the USAAF and redesignated FO-1.

A P-38J was used in experiments with an unusual scheme for mid-air refueling, in which the fighter snagged a drop tank trailed on a cable from a bomber. The USAAF managed to make this work, but decided it was not practical. A P-38J was also fitted with experimental retractable snow ski landing gear, but this idea never reached operational service either.

After the war, a P-38L was experimentally fitted with armament of three .60 in (15.2 mm) machine guns. The .60 in (15.2 mm) caliber cartridge had been developed early in the war for an infantry anti-tank rifle, a type of weapon developed by a number of nations in the 1930s when tanks were lighter but, by 1942, the idea of taking on a tank with a large-caliber rifle was no longer considered to be practical.

The cartridge was not abandoned, with the Americans designing a derivative of the German 15 mm (.59 in) MG 151 cannon around it and designating the weapon the "T17". Although 300 of these guns were built and over six million .60 in (15.2 mm) rounds manufactured, some problems with the weapon were never resolved, and the T17 never saw operational service. The cartridge was expanded and reshaped to fit 20 mm projectiles and became a standard U.S. ammunition after the war. The T17-armed P-38L did not go beyond unsuccessful trials.

Another P-38L was modified after the war as a "super strafer," with eight .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns in the nose and a pod under each wing with two .50 in (12.7 mm) guns, for a total of 12 machine guns. Nothing came of this conversion either.

A P-38L was modified by Hindustan Aeronautics in India as a fast VIP transport, with a comfortable seat in the nose, leather-lined walls, accommodations for refreshments and a glazed nose to give the passenger a spectacular view.

Variants

- XP-38

- United States Army Air Force designation for one prototype Lockheed Model 22 first flown in 1939.[120]

- YP-38

- Redesigned pre-production batch with armament, 13 built.[120]

- P-38-LO

- First production variant with 0.5 in guns and a 37 mm cannon, 30 built.[120][121]

- XP-38A

- Thirtieth P-38-LO modified with a pressurised cockpit.[120][121]

- Lightning I

- Former Armée de l'air order for 667 aircraft (being reduced to 143 Lighting I's) which was taken by the Royal Air Force. Three delivered to RAF, remainder of the order was delivered to USAAF. Utilized C-series V-1710-33 engines without turbochargers and right hand propeller rotation [122][123]

- Lightning II

- Royal Air Force designation for cancelled order of 524 aircraft using F-series V-1710 engines. Only Lightning II built was retained by USAAF for testing, the rest of the order was completed as P-38F-13-LO, P-38F-15-LO, P-38G-13-LO, and P-38G-15-LO aircraft [122][123]

- P-322-I

- 22 Lightning I's of the 143 built were retained by the USAAF for training and testing. Most were unarmed, although some retained the Lighting I armament of 2 × .50 cals and 2 x .30 cals [120][124]

- P-322-II

- 121 P-322-I's re-engined with the V-1710-27/-29 and used for training. Most were unarmed [120][124]

- P-38B

- Proposed variant of the P-38A, not built.[120]

- P-38C

- Proposed variant of the P-38A, not built.[120]

- P-38D

- Production variant with modified tailplane incidence, self-sealing fuel tanks, 36 built.[120]

- P-38E

- Production variant with revised hydraulic system, 20 mm cannon rather than the 37 mm of earlier variants, 210 built.[120]

- P-38F

- Production variant with inboard underwing racks for drop tanks or 2000 lb of bombs, 527 built.[120]

- P-38G

- Production variant with modified radio equipment, 1082 built.[120]

- P-38H

- Production variant capable of carrying 3200 lb of underwing bombs and an automatic oil radiator flaps, 601 built.[120]

- P-38J

- Production variant with improvements to each batch, including chin radiators, flat bullet proof windscreens, power-boosted ailerons and increased fuel capacity, 2970 built. Some modified to pathfinder configuration and to F-5C, F-5E and F-5F.[120]

- P-38K

- With 1425 hp engines with larger broad-bladed propellers, one built, a P-38E was also converted to the same standard as the XP-38K.[120]

- P-38L

- With 1600 hp engines, 3923 built which included 113 built at Vultee, later conversions to pathfinders and F-5G.[120]

- TP-38L

- Two P-38Ls converted as tandem seated operational trainers.[120]

- P-38M

- Conversion of P-38L as a radar-equipped night-fighter.[120]

- F-4

- Photo-reconnaissance variant of the P-38E, 99 built.[125]

- F-4A

- Photo-reconnaissance variant of the P-38F, 20 built.[125]

- F-5A

- Reconnaissance variant of the P-38G, 181 built.[125]

- F-5B

- Reconnaissance variant of the P-38J, 200 built, four later to the United States Navy as FO-1.[125]

- F-5C

- Reconnaissance variant of the P-38J, 123 conversions.[125]

- XF-5D

- Prone-observer variant, one conversion from a F-5A.[125]

- F-5E

- Reconnaissance variant converted from the P-38J and P-38L, 705 converted.[125]

- F-5F

- Reconnaissance variant conversions of the P-38L.[125]

- F-5G

- Reconnaissance variant conversions of the P-38L, had a different camera configuration from the F-5F.[125]

- XFO-1

- United States Navy designation for four F-5Bs operated for evaluation.[126]

Operators

- Military

-

Australia

Australia -

Republic of China

Republic of China -

Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic -

.svg.png) Free France

Free France -

France

France -

Honduras

Honduras -

_crowned.svg.png) Kingdom of Italy

Kingdom of Italy -

Italy

Italy -

Portugal

Portugal -

United Kingdom

United Kingdom -

.svg.png) United States

United States

Civil

Noted P-38s

YIPPEE

The 5,000th Lightning built, a P-38J-20-LO, 44-23296, was painted bright vermilion red, and had the name YIPPEE painted on the underside of the wings in big white letters as well as the signatures of hundreds of factory workers. This and other aircraft were used by a handful of Lockheed test pilots including Milo Burcham, Jimmie Mattern and Tony LeVier in remarkable flight demonstrations, performing such stunts as slow rolls at treetop level with one prop feathered to dispel the myth that the P-38 was unmanageable.[127][128]

In-flight footage of the YIPPEE P-38 can be seen in the pilot episode of the Green Acres television series.

Glacier Girl

On July 15, 1942, a flight of six P-38s and two B-17 bombers, with a total of 25 crew members on board, took off from Presque Isle Air Base in Maine headed for the U.K. What followed was a harrowing and life-threatening landing of the entire squadron on a remote ice cap in Greenland. Miraculously, none of the crew was lost and they were all rescued and returned safely home after spending several days on the desolate ice.

Fifty years later a small group of aviation enthusiasts decided to locate those aircraft, which had come to be known as "The Lost Squadron", and to recover one of the lost P-38s. It turned out to be no easy task, as the planes had been buried under 25 stories of ice and drifted over a mile from their original location. The recovered P-38, dubbed "Glacier Girl", was eventually restored to airworthiness.

Surviving aircraft

Noted P-38 pilots

Richard Bong and Thomas McGuire

The American ace of aces and his closest competitor both flew Lightnings as they tallied 40 and 38 victories respectively. Majors Richard I. "Dick" Bong and Thomas B. "Tommy" McGuire of the USAAF competed for the top position. Both men were awarded the Medal of Honor.

McGuire was killed in air combat in January 1945 over the Philippines, after accumulating 38 confirmed kills, making him the second-ranking American ace. Bong was rotated back to the United States as America's ace of aces, after making 40 kills, becoming a test pilot. He was killed on 6 August 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Japan, when his Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star jet fighter flamed out on takeoff.

_and_Charles_Lindbergh_(R).jpg)

Charles Lindbergh

The famed aviator Charles Lindbergh toured the South Pacific as a civilian contractor for United Aircraft Corporation, comparing and evaluating performance of single- and twin-engined fighters for Vought. He worked to improve range and load limits of the Vought F4U Corsair, flying both routine and combat strafing missions in Corsairs alongside Marine pilots.

Everywhere Lindbergh went in the South Pacific, he was accorded the normal preferential treatment of a visiting colonel, although he had resigned his Air Corps Reserve colonel's commission three years before. In Hollandia, Lindbergh attached himself to the 475th FG, flying P-38s. Although new to the aircraft, Lindbergh was instrumental in extending the range of the P-38 through improved throttle settings, or engine-leaning techniques, notably by reducing engine speed to 1,600 rpm, setting the carburetors for auto-lean and flying at 185 mph (298 km/h) indicated airspeed which reduced fuel consumption to 70 gal/h, about 2.6 mpg. This combination of settings had been considered dangerous and would upset the fuel mixture, causing an explosion.[129]

While with the 475th, he held training classes and took part in a number of Army Air Corps combat missions. On 28 July 1944, Lindbergh shot down a Mitsubishi Ki-51 "Sonia" flown expertly by the veteran commander of 73rd Independent Flying Chutai, Imperial Japanese Army Captain Saburo Shimada. In an extended, twisting dogfight in which many of the participants ran out of ammunition, Shimada turned his aircraft directly toward Lindbergh who was just approaching the combat area. Lindbergh fired in a defensive reaction brought on by Shimada's apparent head-on ramming attack. Hit by cannon and machine gun fire, the "Sonia's" propeller visibly slowed, but Shimada held his course. Lindbergh pulled up at the last moment to avoid collision as the damaged "Sonia" went into a steep dive, hit the ocean and sank. Lindbergh's wingman, ace Joseph E. "Fishkiller" Miller, Jr., had also scored hits on the "Sonia" after it had begun its fatal dive, but Miller was certain the kill credit was Lindbergh's. The unofficial kill was not entered in the 475th's war record. On 12 August 1944, Lindbergh left Hollandia to return to the United States.[130]

Charles MacDonald

The seventh-ranking American ace, Charles H. MacDonald, flew a Lightning against the Japanese, scoring 27 kills in his famous aircraft, the Putt Putt Maru.

Robin Olds

Robin Olds was the last P-38 ace in the Eighth Air Force and the last in the ETO. Flying a P-38J, he downed five German fighters on two separate missions over France and Germany. He subsequently transitioned to P-51s and scored seven more kills. After World War II, he flew F-4 Phantom IIs in Vietnam, ending his career as brigadier general with 16 kills.

John H. Ross

Ross is a decorated World War II pilot who flew 96 missions for the U.S. Army Air Forces under the U.S. 8th Air Force's 7th Reconnaissance Group in the 22nd Reconnaissance Squadron. Ross flew the Lockheed P-38 Lightning as a photoreconnaissance pilot out of RAF Mount Farm in England during the war. He received 11 medals and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross twice for missions that were integral to Allied victory at the Battle of the Bulge.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry