Clutch

A clutch is a mechanical device which engages and disengages power transmission especially from driving shaft to driven shaft.

In the simplest application, clutches connect and disconnect two rotating shafts (drive shafts or line shafts). In these devices, one shaft is typically attached to an engine or other power unit (the driving member) while the other shaft (the driven member) provides output power for work. While typically the motions involved are rotary, linear clutches are also possible.

In a torque-controlled drill, for instance, one shaft is driven by a motor and the other drives a drill chuck. The clutch connects the two shafts so they may be locked together and spin at the same speed (engaged), locked together but spinning at different speeds (slipping), or unlocked and spinning at different speeds (disengaged).

Inter-locking Parts clutches

This type of clutch has protruding circular edge and a hole for them that engages and disengages during operation. This type is less effective since human foot or hand power on clutching reaches about 10 KN or 1,000 kg.

Friction clutches

The vast majority of clutches ultimately rely on frictional forces for their operation. The purpose of friction clutches is to connect a moving member to another that is moving at a different speed or stationary, often to synchronize the speeds, and/or to transmit power. Usually, as little slippage (difference in speeds) as possible between the two members is desired.

Materials

Various materials have been used for the disc-friction facings, including asbestos in the past. Modern clutches typically use a compound organic resin with copper wire facing or a ceramic material. Ceramic materials are typically used in heavy applications such as racing or heavy-duty hauling, though the harder ceramic materials increase flywheel and pressure plate wear.

In the case of "wet" clutches, composite paper materials are very common. Since these "wet" clutches typically use an oil bath or flow-through cooling method for keeping the disc pack lubricated and cooled, very little wear is seen when using composite paper materials.

Push/pull

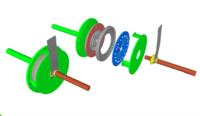

Friction-disc clutches generally are classified as push type or pull type depending on the location of the pressure plate fulcrum points. In a pull-type clutch, the action of pressing the pedal pulls the release bearing, pulling on the diaphragm spring and disengaging the vehicle drive. The opposite is true with a push type, the release bearing is pushed into the clutch disengaging the vehicle drive. In this instance, the release bearing can be known as a thrust bearing (as per the image above).

Dampers

A clutch damper is a device that softens the response of the clutch engagement/disengagement. In automotive applications, this is often provided by a mechanism in the clutch disc centres. In addition to the damped disc centres, which reduce driveline vibration, pre-dampers may be used to reduce gear rattle at idle by changing the natural frequency of the disc. These weaker springs are compressed solely by the radial vibrations of an idling engine. They are fully compressed and no longer in use once the main damper springs take up drive.

Load

Mercedes truck examples: A clamp load of 33 kN is normal for a single plate 430. The 400 Twin application offers a clamp load of a mere 23 kN. Bursts speeds are typically around 5,000 rpm with the weakest point being the facing rivet.

Manufacturing

Modern clutch development focuses its attention on the simplification of the overall assembly and/or manufacturing method. For example, drive straps are now commonly employed to transfer torque as well as lift the pressure plate upon disengagement of vehicle drive. With regard to the manufacture of diaphragm springs, heat treatment is crucial. Laser welding is becoming more common as a method of attaching the drive plate to the disc ring with the laser typically being between 2-3KW and a feed rate 1m/minute.

Multiple plate clutch

This type of clutch has several driving members interleaved or "stacked" with several driven members. It is used in racing cars including Formula 1, IndyCar, World Rally and even most club racing. Multiplate clutches see much use in drag racing, which requires the best acceleration possible, and is notorious for the abuse the clutch is subjected to. Thus motorcycles, automatic transmissions and in some diesel locomotives with mechanical transmissions. It is also used in some electronically controlled all-wheel drive systems as well as in some transfer cases. They can also be found in some heavy machinery such as tanks and AFV's (T-54) and earthmoving equipment (front-end loaders, bulldozers), as well as components in certain types of limited slip differentials. The benefit in the case of motorsports is that you can achieve the same total friction force with a much smaller overall diameter (or conversely, a much greater friction force for the same diameter, important in cases where a vehicle is modified with greater power, yet the maximum physical size of the clutch unit is constrained by the clutch housing). In motorsports vehicles that run at high engine/drivetrain speeds, the smaller diameter reduces rotational inertia, making the drivetrain components accelerate more rapidly, as well as reducing the angular velocity of the outer areas of the clutch unit, which could become highly stressed and fail at the extremely high drivetrain rotational rates achieved in sports such as Formula 1 or drag racing. In the case of heavy equipment, which often deal with very high torque forces and drivetrain loads, a single plate clutch of the necessary strength would be too large to easily package as a component of the driveline.

Another, different theme on the multiplate clutch is the clutches used in the fastest classes of drag racing, highly specialized, purpose-built cars such as Top Fuel or Funny Cars. These cars are so powerful that to attempt a start with a simple clutch would result in complete loss of traction. To avoid this problem, Top Fuel cars actually use a single, fixed gear ratio, and a series of clutches that are engaged one at a time, rather than in unison, progressively allowing more power to the wheels. A single one of these clutch plates (as designed) can not hold more than a fraction of the power of the engine, so the driver starts with only the first clutch engaged. This clutch is overwhelmed by the power of the engine, allowing only a fraction of the power to the wheels, much like "slipping the clutch" in a slower car, but working not requiring concentration from the driver. As speed builds, the driver pulls a lever, which engages a second clutch, sending a bit more of the engine power to the wheels, and so on. This continues through several clutches until the car has reached a speed where the last clutch can be engaged. With all clutches engaged, the engine is now sending all of its power to the rear wheels. This is far more predictable and repeatable than the driver manually slipping the clutch himself and then shifting through the gears, given the extreme violence of the run and the speed at which is all unfolds. Another benefit is that there is no need to break the power flow in order to swap gears (a conventional manual cannot transmit power while between gears, which is important because 1/100ths of a second are important in Top Fuel races). A traditional multiplate clutch would be more prone to overheating and failure, as all the plates must be subjected to heat and friction together until the clutch is fully engaged, while a Top Fuel car keeps its last clutches in "reserve" until the cars speed allows full engagement. It is relatively easy to design the last stages to be much more powerful than the first, in order to ensure they can absorb the power of the engine even if the first clutches burn out or overheat from the extreme friction.

Wet vs. dry systems

A wet clutch is immersed in a cooling lubricating fluid that also keeps surfaces clean and provides smoother performance and longer life. Wet clutches, however, tend to lose some energy to the liquid. Since the surfaces of a wet clutch can be slippery (as with a motorcycle clutch bathed in engine oil), stacking multiple clutch discs can compensate for the lower coefficient of friction and so eliminate slippage under power when fully engaged. The Hele-Shaw clutch was a wet clutch that relied entirely on viscous effects, rather than on friction.[1]

A dry clutch, as the name implies, is not bathed in liquid and uses friction to engage.

Centrifugal clutch

A centrifugal clutch is used in some vehicles (e.g., mopeds) and also in other applications where the speed of the engine defines the state of the clutch, for example, in a chainsaw. This clutch system employs centrifugal force to automatically engage the clutch when the engine rpm rises above a threshold and to automatically disengage the clutch when the engine rpm falls low enough. See Saxomat and Variomatic.

Cone clutch

As the name implies, a cone clutch has conical friction surfaces. The cone's taper means that a given amount of movement of the actuator makes the surfaces approach (or recede) much more slowly than in a disc clutch. As well, a given amount of actuating force creates more pressure on the mating surfaces. The best known example of a cone clutch is a synchronizer ring in a manual transmission. The synchronizer ring is responsible for "synchronizing" the speeds of the shift hub and the gear wheel to ensure a smooth gear change.

Torque limiter

Also known as a slip clutch or safety clutch, this device allows a rotating shaft to slip when higher than normal resistance is encountered on a machine. An example of a safety clutch is the one mounted on the driving shaft of a large grass mower. The clutch yields if the blades hit a rock, stump, or other immobile object, thus avoiding a potentially damaging torque transfer to the engine, possibly twisting or fracturing the crankshaft.

Motor-driven mechanical calculators had these between the drive motor and gear train, to limit damage when the mechanism jammed, as motors used in such calculators had high stall torque and were capable of causing damage to the mechanism if torque wasn't limited.

Carefully designed clutches operate, but continue to transmit maximum permitted torque, in such tools as controlled-torque screwdrivers.

Non-slip clutches

Some clutches are not designed to slip; torque may only be transmitted either fully engaged or disengaged to avoid catastrophic damage. An example of this is the dog clutch, most commonly used in non-synchromesh transmissions.

Major types by application

Vehicular (general)

There are multiple designs of vehicle clutch, but most are based on one or more friction discs pressed tightly together or against a flywheel using springs. The friction material varies in composition depending on many considerations such as whether the clutch is "dry" or "wet". Friction discs once contained asbestos, but this has been largely discontinued. Clutches found in heavy duty applications such as trucks and competition cars use ceramic plates that have a greatly increased friction coefficient. However, these have a "grabby" action generally considered unsuitable for passenger cars. The spring pressure is released when the clutch pedal is depressed thus either pushing or pulling the diaphragm of the pressure plate, depending on type. Raising the engine speed too high while engaging the clutch causes excessive clutch plate wear. Engaging the clutch abruptly when the engine is turning at high speed causes a harsh, jerky start. This kind of start is necessary and desirable in drag racing and other competitions, where speed is more important than comfort.

Automobile powertrain

In a modern car with a manual transmission the clutch is operated by the left-most pedal using a hydraulic or cable connection from the pedal to the clutch mechanism. On older cars the clutch might be operated by a mechanical linkage. Even though the clutch may physically be located very close to the pedal, such remote means of actuation are necessary to eliminate the effect of vibrations and slight engine movement, engine mountings being flexible by design. With a rigid mechanical linkage, smooth engagement would be near-impossible because engine movement inevitably occurs as the drive is "taken up."

The default state of the clutch is engaged - that is the connection between engine and gearbox is always "on" unless the driver presses the pedal and disengages it. If the engine is running with the clutch engaged and the transmission in neutral, the engine spins the input shaft of the transmission but power is not transmitted to the wheels.

The clutch is located between the engine and the gearbox, as disengaging it is usually required to change gear. Although the gearbox does not stop rotating during a gear change, there is no torque transmitted through it, thus less friction between gears and their engagement dogs. The output shaft of the gearbox is permanently connected to the final drive, then the wheels, and so both always rotate together, at a fixed speed ratio. With the clutch disengaged, the gearbox input shaft is free to change its speed as the internal ratio is changed. Any resulting difference in speed between the engine and gearbox is evened out as the clutch slips slightly during re-engagement.

Clutches in typical cars are mounted directly to the face of the engine's flywheel, as this already provides a convenient large diameter steel disk that can act as one driving plate of the clutch. Some racing clutches use small multi-plate disk packs that are not part of the flywheel. Both clutch and flywheel are enclosed in a conical bellhousing, which (in a rear-wheel drive car) usually forms the main mounting for the gearbox.

A few cars, notably the Alfa Romeo Alfetta, Porsche 924, and Chevrolet Corvette (since 1997), sought a more even weight distribution between front and back[note 1] by placing the weight of the transmission at the rear of the car, combined with the rear axle to form a transaxle. The clutch was mounted with the transaxle and so the propeller shaft rotated continuously with the engine, even when in neutral gear or declutched.

Motorcycles

Motorcycles typically employ a wet clutch with the clutch riding in the same oil as the transmission. These clutches are usually made up of a stack of alternating plain steel and friction plates. Some plates have lugs on their inner diameters that lock them to the engine crankshaft. Other plates have lugs on their outer diameters that lock them to a basket that turns the transmission input shaft. A set of coil springs or a diaphragm spring plate force the plates together when the clutch is engaged.

On motorcycles the clutch is operated by a hand lever on the left handlebar. No pressure on the lever means that the clutch plates are engaged (driving), while pulling the lever back towards the rider disengages the clutch plates through cable or hydraulic actuation, allowing the rider to shift gears or coast. Racing motorcycles often use slipper clutches to eliminate the effects of engine braking, which, being applied only to the rear wheel, can cause instability.

Automobile non-powertrain

Cars use clutches in places other than the drive train. For example, a belt-driven engine cooling fan may have a heat-activated clutch. The driving and driven members are separated by a silicone-based fluid and a valve controlled by a bimetallic spring. When the temperature is low, the spring winds and closes the valve, which lets the fan spin at about 20% to 30% of the shaft speed. As the temperature of the spring rises, it unwinds and opens the valve, allowing fluid past the valve, makes the fan spin at about 60% to 90% of shaft speed. Other clutches—such as for an air conditioning compressor—electronically engage clutches using magnetic force to couple the driving member to the driven member.

Other clutches and applications

- Belt clutch: Used on agricultural equipment, lawn mowers, tillers, and snow blowers. Engine power is transmitted via a set of belts that are slack when the engine is idling, but an idler pulley can tighten the belts to increase friction between the belts and the pulleys.

- Dog clutch: Utilized in automobile manual transmissions mentioned above. Positive engagement, non-slip. Typically used where slipping is not acceptable and space is limited. Partial engagement under any significant load can be destructive.

- Hydraulic clutch: The driving and driven members are not in physical contact; coupling is hydrodynamic.

- Electromagnetic clutch are, typically, engaged by an electromagnet that is an integral part of the clutch assembly. Another type, magnetic particle clutches, contain magnetically influenced particles in a chamber between driving and driven members—application of direct current makes the particles clump together and adhere to the operating surfaces. Engagement and slippage are notably smooth.

- Overrunning clutch or freewheel: If some external force makes the driven member rotate faster than the driver, the clutch effectively disengages. Examples include:

- Borg-Warner overdrive transmissions in cars

- Ratchet: typical bicycles have these so that the rider can stop pedaling and coast

- An oscillating member where this clutch can then convert the oscillations into intermittent linear or rotational motion of the complimentary member; others use ratchets with the pawl mounted on a moving member

- The winding knob of a camera employs a (silent) wrap-spring type as a clutch in winding and as a brake in preventing it from being turned backwards.

- The rotor drive train in helicopters uses a freewheeling clutch to disengage the rotors from the engine in the event of engine failure, allowing the craft to safely descend by autorotation.

- Wrap-spring clutches: These have a helical spring, typically wound with square-cross-section wire. These were developed in the late 19th and early 20th century.[2][3] In simple form the spring is fastened at one end to the driven member; its other end is unattached. The spring fits closely around a cylindrical driving member. If the driving member rotates in the direction that would unwind the spring the spring expands minutely and slips although with some drag. Because of this, spring clutches must typically be lubricated with light oil. Rotating the driving member the other way makes the spring wrap itself tightly around the driving surface and the clutch locks up very quickly. The torque required to make a spring clutch slip grows exponentially with the number of turns in the spring, obeying the capstan equation.

Specialty clutches and applications

Single-revolution clutch

Single-revolution clutches were developed in the 19th century to power machinery such as shears or presses where a single pull of the operating lever or (later) press of a button would trip the mechanism, engaging the clutch between the power source and the machine's crankshaft for exactly one revolution before disengaging the clutch. When the clutch is disengaged and the driven member is stationary. Early designs were typically dog clutches with a cam on the driven member used to disengage the dogs at the appropriate point.[4][5]

Greatly simplified single-revolution clutches were developed in the 20th century, requiring much smaller operating forces and in some variations, allowing for a fixed fraction of a revolution per operation.[6] Fast action friction clutches replaced dog clutches in some applications, eliminating the problem of impact loading on the dogs every time the clutch engaged.[7][8]

In addition to their use in heavy manufacturing equipment, single-revolution clutches were applied to numerous small machines. In tabulating machines, for example, pressing the operate key would trip a single revolution clutch to process the most recently entered number.[9] In typesetting machines, pressing any key selected a particular character and also engaged a single rotation clutch to cycle the mechanism to typeset that character.[10] Similarly, in teleprinters, the receipt of each character tripped a single-revolution clutch to operate one cycle of the print mechanism.[11]

In 1928, Frederick G. Creed developed a single-turn spring clutch (see above) that was particularly well suited to the repetitive start-stop action required in teleprinters.[12] In 1942, two employees of Pitney Bowes Postage Meter Company developed an improved single turn spring clutch.[13] In these clutches, a coil spring is wrapped around the driven shaft and held in an expanded configuration by the trip lever. When tripped, the spring rapidly contracts around the power shaft engaging the clutch. At the end of one revolution, if the trip lever has been reset, it catches the end of the spring (or a pawl attached to it) and the angular momentum of the driven member releases the tension on the spring. These clutches have long operating lives, many have cycled for tens and perhaps hundreds of millions of cycles without need of maintenance other than occasional lubrication.

Cascaded-pawl single-revolution clutches

These superseded wrap-spring single-revolution clutches in page printers, such as teleprinters, including the Teletype Model 28 and its successors, using the same design principles. IBM Selectric typewriters also used them. These are typically disc-shaped assemblies mounted on the driven shaft. Inside the hollow disc-shaped drive drum are two or three freely floating pawls arranged so that when the clutch is tripped, the pawls spring outward much like the shoes in a drum brake. When engaged, the load torque on each pawl transfers to the others to keep them engaged. These clutches do not slip once locked up, and they engage very quickly, on the order of milliseconds. A trip projection extends out from the assembly. If the trip lever engaged this projection, the clutch was disengaged. When the trip lever releases this projection, internal springs and friction engage the clutch. The clutch then rotates one or more turns, stopping when the trip lever again engages the trip projection.

Kickback clutch-brakes

These mechanisms were found in some types of synchronous-motor-driven electric clocks. Many different types of synchronous clock motors were used, including the pre-World War II Hammond manual-start clocks. Some types of self-starting synchronous motors always started when power was applied, but in detail, their behaviour was chaotic and they were equally likely to start rotating in the wrong direction. Coupled to the rotor by one (or possibly two) stages of reduction gearing was a wrap-spring clutch-brake. The spring did not rotate. One end was fixed; the other was free. It rode freely but closely on the rotating member, part of the clock's gear train. The clutch-brake locked up when rotated backwards, but also had some spring action. The inertia of the rotor going backwards engaged the clutch and wound the spring. As it unwound, it restarted the motor in the correct direction. Some designs had no explicit spring as such—but were simply compliant mechanisms. The mechanism was lubricated and wear did not present a problem.

Lock-up clutch

A Lock-up clutch is used in some automatic transmissions for motor vehicles. Above a certain speed (usually 60 km/h) it locks the torque converter to minimise power loss and improve fuel efficiency.[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ This more even weight distribution gives better handling, particularly for fast cornering. It offers much of the balance advantage of a mid-engined layout, whilst still using a front-engined rear-drive bodyshell.

References

- ↑ "From the Hele-Shaw Experiment to IntegrableSystems: A Historical Overview" (PDF). University of Bergen. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ↑ Analdo M. English, Friction-Clutch, US 255957, granted Apr. 4 1882.

- ↑ Charles C. Tillotson, Power-Transmission Clutch, US 850981, granted Apr. 23, 1907.

- ↑ Frank Wheeler, Clutch and stop mechanism for presses, US 470797, granted Dec. 14, 1891.

- ↑ Samuel Trethewey, Clutch, US 495686, granted Apr. 18, 1893.

- ↑ Fred. R. Allen, Clutch, US 1025043, granted Apr. 30, 1912.

- ↑ John J. Zeitz, Friction-clutch, US 906181, granted Dec. 8, 1908.

- ↑ William Lautenschlager, Friction Clutch, US 1439314, granted Dec. 19, 1922.

- ↑ Fred. M. Carroll, Key adding device for tabulating machines, US 1848106, granted Mar. 8, 1932.

- ↑ Clifton Chisholm, Typesetting machine, US 1889914, granted Dec. 6, 1932.

- ↑ Arthur H, Adams, Selecting and typing means for printing telegraphs, US 2161840, issued Jun. 13, 1928.

- ↑ Frederick G. Creed, Clutch Mechanism, US 1659724, granted Feb. 21, 1928

- ↑ Alva G. Russell, Alfred Burkhardt, and Samuel E. Calhoun, Spring Clutch, US 2298970, granted Oct. 13, 1942.

- ↑ "What is Lock-up Clutch Mechanism?". Your Online Mechanic. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

Further reading

- Sclater, Neil. (2011). "Clutches and brakes." Mechanisms and Mechanical Devices Sourcebook. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 211–234. ISBN 9780071704427. Drawings and designs of various clutches.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clutch (coupling). |

- HowStuffWorks has a detailed explanation of the working of an automobile clutch.